Empowering Sustainable Tourism Through Simulation: Evidence and Trends in the Tourism 5.0 Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify the main methodologies employed, such as Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), System Dynamics (SD), and Digital Twin (DT), among others;

- Map application areas and trends related to the Experience 5.0 paradigm;

- Discuss barriers and opportunities in adopting these tools;

- Suggest directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Core Concepts of Simulation

2.2. The Tourism Experience 5.0

2.3. Previous Reviews and Identified Research Gaps

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

- o

- (“Simulation” OR “Modeling”) AND “Tourism”

- o

- (“Digital twin”) AND “Tourism”

- o

- (“Agent-based modeling”) AND “Tourism”

- o

- “Virtual reality” AND “Tourism”

- o

- “Tourism 5.0”

- o

- “Tourism experience” AND “Simulation”

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Selection and Data Processing

- ▪

- Identification—340 articles initially retrieved.

- ▪

- Screening—duplicates removed (n = 44), resulting in 296 unique records.

- ▪

- Eligibility—title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 226 studies. Of the 70 remaining, 36 were rejected for thematic irrelevance (n = 18), insufficient methodological rigor (n = 15), or excessive technical focus (n = 3).

- ▪

- Inclusion—34 articles met all criteria and were included in the final analysis.

3.4. Analytical Tools

- VOSviewer—used to construct two maps:

- i.

- a keyword co-occurrence network revealing thematic clusters and the conceptual structure of the field;

- ii.

- a keyword density map highlighting the most frequent and interconnected terms within the analyzed literature.

- Synthesis Matrix—used to consolidate variables such as author, year, geographical context, simulation methodology, benefits, limitations, and main conclusions.

- Thematic Analysis—categorization of the 34 articles into four conceptual axes:

- Sustainability and Environmental Impacts,

- Planning and Strategic Management,

- Digital Experiences and Tourist Interaction, and

- Smart Tourism and Decision Support Models.

4. Results

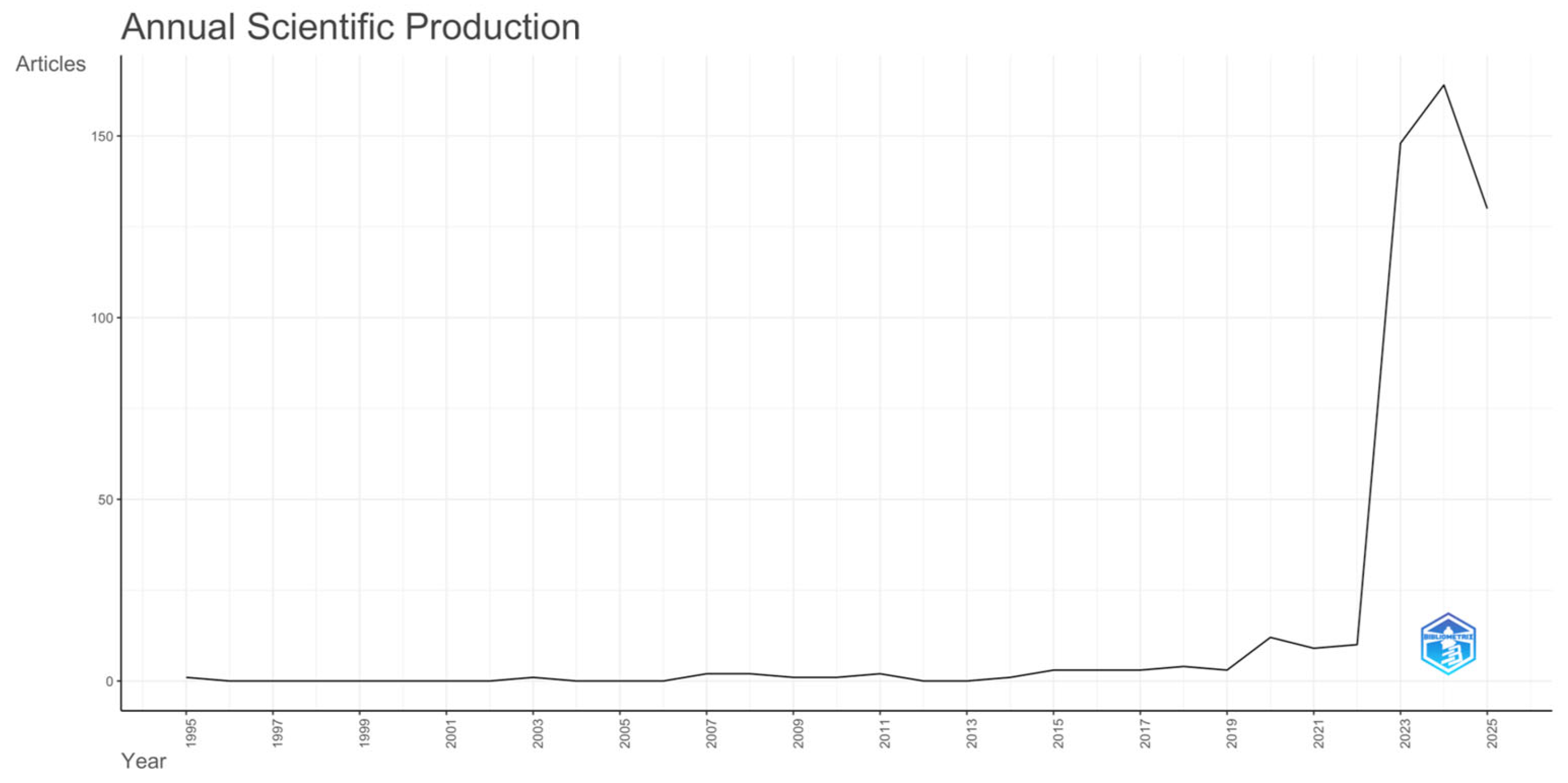

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis

- Sustainability and planning policies (green)—includes terms such as system dynamics, policy, carrying capacity, and sustainability, referring to policy modeling and sustainable destination management.

- Tourism and demand forecasting (blue)—includes keywords such as tourism, demand forecasting, prediction, and resilience, focusing on mobility patterns and tourist behavior.

- Simulation and mobility (yellow)—includes simulation, ABM, traffic, and decision support, emphasizing tourist flows, congestion, and decision-making processes.

- Digitalization and smart destinations (red)—includes digital twin, smart tourism, big data, augmented reality, and smart destination, representing technological evolution and the integration of real-time data.

4.2. Geographical and Sectoral Differences in the Application of Simulation

4.3. Emerging Technologies and Integration with Smart Tourism

4.4. Barriers and Limitations to the Adoption of Simulation in Tourism

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- i.

- conceptual axes (smart tourism, digital experiences, planning, and sustainability);

- ii.

- simulation methodologies (ABM, SD, DT, and hybrids);

- iii.

- emerging technologies (AI, IoT, big data, augmented reality); and

- iv.

- adoption barriers (technical, organizational, economic, and cultural).

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubino, G.; Gattuso, D.; Longo, F. Exploring Industry 4.0 Technologies in Tourism. A Literature Review. In Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 3182–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, A.; Ben Youssef, A.; Maherzi Zahar, T. The Role of Digital Tourism Platforms in Advancing Sustainable Development Goals in the Industry 4.0 Era. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Ye, Q. Agent-based modeling and simulation of tourism market recovery strategy after COVID-19 in Yunnan, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.M.; Maddison, D.J.; Tol, R.S.J. Climate change and international tourism: A simulation study. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student, J.; Kramer, M.R.; Steinmann, P. Simulating emerging coastal tourism vulnerabilities: An agent-based modelling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.A.; Greiner, R.; Mcdonald, D.; Lyne, V. The Tourism Futures Simulator: A systems thinking approach. Environ. Model. Softw. 1998, 14, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. Computational modelling and simulations in tourism: A primer. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2020, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The Use of Digital Twins to Address Smart Tourist Destinations’ Future Challenges. Platforms 2024, 2, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štekerová, K.; Zelenka, J.; Kořínek, M. Agent-Based Modelling in Visitor Management of Protected Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Parada, J.; Peña-Miranda, D.D. Agent-Based Model Applied for the Study of Overtourism in an Urban Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Simulation of tourism carbon emissions based on system dynamics model. Phys. Chem. Earth 2023, 129, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Jang, W.Y.; Park, T.H. Key Attributes Driving Yacht Tourism: Exploring Tourist Preferences Through Conjoint Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, T.A.P.; Yusuf, R.; Irawan, K.; Juhana, A.; Elindriyani, R.V.; Dermawan, K.F. Agent-Based Modeling on Traveler Behavior and Travel Destination Development with Case Study of Indonesian Tourism. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Interactive Digital Media, ICIDM 2020, Bandung, Indonesia, 14–15 December 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, M. Application of computer virtual simulation technology in tourism industry. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering, ICBAIE 2022, Xi’an, China, 15–17 July 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Platanakis, E.; Stafylas, D.; Sutcliffe, C. Identifying a destination’s optimal tourist market mix: Does a superior portfolio model exist? Tour. Manag. 2023, 96, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Abreu, F.B.; Marinheiro, R.N.; Boavida-Portugal, I.; Lopes, A.; Santos, T.M.; De Almeida, D.S.; Simões, R. A digital transformation approach to scaffold tourism crowding management: Pre-factum, on-factum, and post-factum. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering, ECTI DAMT and NCON 2024, Chiang-mai, Thailand, 31 January–3 February 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhady, S.; Shaban, A. A Simulation Modeling Approach for the Techno-Economic Analysis of the Integration of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems in Tourism Districts. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Chu, Q.; Chen, G. Design of Smart Tourism Visual Analysis Platform Based on Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms, EEBDA 2024, Changchun, China, 27–29 February 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1300–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieanwatana, K.; Vongvit, R. Virtual reality in tourism: The impact of virtual experiences and destination image on the travel intention. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Silva, E.S.; Hassani, H.; Heravi, S. Forecasting tourism growth with State-Dependent Models. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Hachiya, N.; Aikoh, T.; Shoji, Y.; Nishinari, K.; Satake, A. A decision support model for traffic congestion in protected areas: A case study of Shiretoko National Park. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, H. Simulation of Big Data AR Intelligent Tourism System Based on Improved Apriori Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Robot Systems, AIARS 2024, Bristol, UK, 29–31 July 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, Y.; Tian, X. A multi-agent model of traffic simulation around urban scenic spots: From the perspective of tourist behaviors. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncsiper, C. Modeling the number of tourist arrivals in the United States employing deep learning networks. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, W.H.; Zeng, Z. Tourism Demand Forecasting Based on a Hybrid Temporal Neural Network Model for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, F.; Wu, H.; Liu, Z.; Fang, S. Digital Twin Platform Design for Zhejiang Rural Cultural Tourism Based on Unreal Engine. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Culture-Oriented Science and Technology, CoST 2022, Lanzhou, China, 18–21 August 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebraoui, S.; Nemiche, M. Agent-Based Model for Moroccan Inbound Tourism: Social Influence and Destination Choice. In Proceedings of the 2024 World Conference on Complex Systems, WCCS 2024, Mohammedia, Morocco, 11–14 November 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altar, J.R.B.; Dellova, C.A.P.; Resco, A.M.; Bartiquin, A.M.; Dinaga, M.R.D.; Costales, J.A. An Integrated Intranet-Based Simulation System for College of Hospitality and Tourism Management of EARIST Manila. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Computer Applications Technology, CCAT 2024, Wenzhou, China, 15–17 November 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A. Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xu, C.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Law, R. Digital Tourism and Smart Development: State-of-the-Art Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T. Virtual Tourism Simulation System Based on VR Technology. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintciak, A.M.; Bolsunovskaya, M.V.; Burlutskaya, Z.V.; Petryaeva, A.A. High-level simulation model of tourism industry dynamics. Bus. Inform. 2022, 16, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Chen, X.; Du, W.; Han, J. Simulation Research on the Optimization of Rural Tourism System Resilience Based on a Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network—Taking Well-Known Tourist Villages in Heilongjiang Province as Examples. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; van der Borg, J. Venice and overtourism: Simulating sustainable development scenarios through a tourism carrying capacity model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria (I) | Exclusion Criteria (E) | Potential Future Research Question |

|---|---|---|

| Studies that explicitly apply simulation methodologies (ABM, SD, DT, VR, etc.) in tourism contexts. | Studies without a substantive link between tourism and simulation. | How can different simulation approaches be integrated to represent the dynamic behavior of tourists in smart destinations? |

| Publications in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings. | Documents not subject to peer review (white papers, technical reports, dissertations). | How do scientific credibility and methodological rigor influence the adoption of simulation in tourism planning? |

| Studies that explore empirical applications or case studies with validated simulation models. | Purely theoretical or technical studies without empirical demonstration. | How can simulation models support real-time decision-making in tourism destinations? |

| Works addressing themes such as mobility, sustainability, planning, digital experiences, or smart tourism. | Redundant or duplicate publications across databases. | Which thematic areas emerge as priorities for developing digital twins in sustainable tourism? |

| Articles published between 1999 and 2025, in English or Portuguese. | Studies of poor methodological quality or outside the defined time range. | How has simulation research in tourism evolved from early foundational models to digital and post-pandemic applications? |

| (A) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Geographical Context | Simulation Method | Benefits | Limitations | Main Conclusions |

| [1] | Global (Europe and China) | Bibliometric Review (ABM, SD, Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, VR) | Maps technological trends and research gaps | Based only on Scopus data; lacks empirical validation | Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), IoT, and Big Data optimizes tourism planning |

| [2] | Global (Europe and Tunisia) | Theoretical Framework—Industry 4.0 | Links digital platforms to SDGs and sustainability | No empirical validation | Digital platforms promote sustainable tourism |

| [7] | Global/Theoretical | Conceptual framework integrating Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), System Dynamics (SD), and Network Simulation | Provides a comprehensive methodological foundation for applying computational modeling in tourism; supports decision-making and policy design | Theoretical focus; lacks empirical validation or real-world application | Simulation models, when properly designed and validated, are powerful tools for understanding complex tourism systems and supporting evidence-based decision-making |

| [8] | Global (Europe, Asia, Middle East) | Systematic Review on Digital Twins | Real-time simulations and personalized tourist experiences | Cost and cybersecurity issues | Digital Twins optimize tourism operations and visitor experience |

| [16] | Lisbon, Portugal (RESETTING Project) | ABM (GAMA) + Wi-Fi sensors + 3D visualization | Plans, monitors, and predicts tourist overcrowding | Complex calibration and setup required | Integration between simulation and real data improves crowd management |

| [18] | Xining, China | Digital Twin + Monte Carlo + Particle Simulation | Real-time simulation of tourist and safety flows | Single-case study; requires continuous data input | Smart Xining improves tourism management and urban planning |

| [20] | Japan | SDM Models + Monte Carlo Simulation | Accurate forecasting of tourism demand | Requires long data series and high computational power | SDM models outperform ARIMA and Neural Networks in the medium term |

| [21] | Shiretoko National Park, Japan | Cellular Automata Model (CAM) | Forecasts congestion and supports sustainable management | Simplified and seasonal model | Decentralizing entrances and limiting cars reduces congestion |

| [22] | Jilin, China | Big Data + AR + Apriori and FP-Growth algorithms | Provides intelligent recommendations and immersive experiences | High infrastructure and computational cost | Stable and personalized system for real-time tourism management |

| [23] | Xiamen, China | ABM (tourists and vehicles) | Identifies traffic flow thresholds and supports congestion management | Model restricted to one urban area | Policies for tourist flow reduction alleviate urban congestion |

| [24] | USA | Deep Learning (MLP Neural Network) | High accuracy in flow prediction | Data requirements and computational cost | Reliable forecasts optimize tourism planning and mobility |

| [25] | Thailand | BiLSTM–Transformer (Hybrid Neural Network) | Robust forecasting and sustainable planning | High computational cost and data requirements | Hybrid model reduces errors and supports strategic decision-making |

| (B) | |||||

| No. | Geographical Context | Simulation Method | Benefits | Limitations | Main Conclusions |

| [14] | China | Virtual Reality (VR)/Augmented Reality (AR) Simulation (Unity3D + HTC Vive) | Creates immersive experiences and smart destination management | Costs and 5G network dependency | Integrates VR/AR, Big Data, and 5G, boosting hybrid and sustainable tourism |

| [26] | Zhejiang, China (Xitang village) | Digital Twin (UE + GIS + 3D) | Preserves cultural heritage and promotes smart rural tourism | High cost and technological dependency | Improves management and revitalization of cultural tourism through technological integration |

| [19] | Thailand | PLS-SEM (VR) | Demonstrates the positive impact of VR on destination image and travel intention | Limited sample and absence of negative factors | VR experiences strengthen destination image and increase real visit intention |

| [27] | Moroccan tourism network (11 destinations) | ABM with Barabási–Albert social network | Analyzes social influence and digital marketing on tourist behavior | Theoretical model; no empirical validation | Social influence concentrates tourists in popular destinations; balanced promotion reduces congestion |

| [28] | Manila, Philippines (EARIST) | Intranet simulation (Agile-SDLC) | Practical, risk-free training in an educational environment | Academic application; lacks real data | The system meets ISO standards, enhances competencies, and can expand to other sectors |

| [29] | Global (University of Waterloo, Canada) | Conceptual VR modeling | Planning, marketing, and tourism education | Costs and lack of full realism | VR revolutionizes tourism experiences and education, but authenticity remains a barrier |

| [30] | Global | Systematic Literature Review + Bibliometric Analysis (CiteSpace) | Identifies main digital tourism trends, technologies (AI, VR/AR, Big Data, Blockchain) and integration paths for smart tourism | Limited to English-language studies; theoretical synthesis without experimental validation | Digital technologies and smart development redefine the tourism industry through innovation, co-creation, and integration of the digital and real economy |

| [31] | Liaoning, China | VR System (Unity3D + 3ds Max) | Enables immersive virtual visits and reduces pressure on real sites | VR hardware dependency and vertigo issues | Effective system with 90% satisfaction rate, showing strong potential for the future of digital tourism |

| (C) | |||||

| No. | Geographical Context | Simulation Method | Benefits | Limitations | Main Conclusions |

| [3] | Yunnan Province, China | ABM (NetLogo)—post-COVID recovery simulation | Forecasts the impact of pricing and information strategies | Applied to only five destinations; dependent on simulated parameters | Effective pricing strategies; information varies by destination; combination may yield inconsistent results |

| [12] | South Korea (10 marinas) | Conjoint Analysis | Identifies optimal combinations and preferences in nautical tourism | Limited context; does not include external variables | Program and safety are the most valued attributes; ideal combination includes accessibility within <1 h |

| [13] | Indonesia | ABM (NetLogo)—tourist behavior and types of attractions | Optimizes tourist–attraction relationships and maximizes satisfaction | Theoretical simulation; lacks empirical validation | Optimal ratio 2:1:2 between attractions and 2:1 between tourists; balance between satisfaction and boredom |

| [15] | Australia, Greece, Japan, and USA | Tourist portfolio models (Markowitz) | Maximizes revenue and reduces demand instability | Based on static historical data | Market diversification reduces risk and increases revenues; Levels 1 model proves most reliable |

| [32] | Austria | System Dynamics (SD) + CGE | Assesses the impact of tourism on GDP and well-being | Lacks seasonality and detailed regional data | Domestic tourism strengthens GDP and economic resilience |

| (D) | |||||

| No. | Geographical Context | Simulation Method | Benefits | Limitations | Main Conclusions |

| [4] | Global (207 countries) | Econometric and global simulation model | Forecasts effects of climate change on tourism | Aggregated and static data | Climate has less impact than economic factors; colder regions will benefit |

| [5] | Curaçao, Caribbean | ABM—Coasting Model | Understands socioecological vulnerability and supports sustainable adaptation | Exploratory and simplified model | Pollution and low returns increase vulnerability; reducing pollution improves resilience |

| [6] | Douglas Shire and Great Barrier Reef, Australia | Tourism Futures Simulator (System Dynamics) | Assesses scenarios and environmental and economic impacts | Complex model dependent on local data | TFS supports sustainable planning and prevention of environmental overload |

| [9] | Czech Republic | ABM—visitor behavior in natural areas | Analyzes environmental and social impacts and visitor flows | Simplified model dependent on calibration | ABM helps define carrying capacity limits and support sustainable management |

| [10] | Santa Marta, Colombia | ABM (GAMA)—spatial and temporal distribution | Assesses overtourism risk and tests management strategies | Limited data and simplified behavior modeling | Visitor dispersion and digital monitoring reduce overcrowding |

| [11] | Hunan, China | System Dynamics (SD) | Quantifies emissions and supports low-carbon policies | Simplifies external factors and uses aggregated data | Effective model for predicting emissions and supporting sustainable tourism |

| [17] | Fayoum, Egypt | HOMER Grid Simulation (PV/wind + EV) | Reduces emissions and energy costs; promotes sustainable mobility | Limited study area and high initial investment | Hybrid system viable and efficient; reduces CO2 emissions and grid dependence |

| [33] | Heilongjiang, China | LSTM Neural Network + GeoDetector | Identifies resilience factors and predicts rural tourism evolution | Limited to one province; depends on questionnaires | Environmental and institutional factors determine resilience; LSTM more accurate than BP model |

| [34] | Venice, Italy | Fuzzy Linear Programming (TCC) | Simulates sustainable scenarios and defines visitor limits | Parameter uncertainty and local dependency | Venice exceeds sustainable capacity; fuzzy model supports decision-making and urban policies |

| Dimension | Description | Examples of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | Lack of interoperable data, scalability, and computational resources. | [4,8,16,22] |

| Organizational | Lack of technical skills, resistance to innovation, and limited institutional integration. | [5,20,28,32] |

| Economic | High implementation costs and lack of tangible economic returns. | [7,18,29,31] |

| Cultural and Ethical | Resistance to digitalization, lack of trust, and privacy concerns. | [1,3,11,15,17,23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins, S.; Ramos, A.L.; Brito, M. Empowering Sustainable Tourism Through Simulation: Evidence and Trends in the Tourism 5.0 Era. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310850

Martins S, Ramos AL, Brito M. Empowering Sustainable Tourism Through Simulation: Evidence and Trends in the Tourism 5.0 Era. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310850

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Soraia, Ana L. Ramos, and Marlene Brito. 2025. "Empowering Sustainable Tourism Through Simulation: Evidence and Trends in the Tourism 5.0 Era" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310850

APA StyleMartins, S., Ramos, A. L., & Brito, M. (2025). Empowering Sustainable Tourism Through Simulation: Evidence and Trends in the Tourism 5.0 Era. Sustainability, 17(23), 10850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310850