Demand Segmentation for Sustainable Adventure Destination Management: A Study of Santa Elena, Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivations in Adventure Tourism

2.2. Segmentation of Adventure Tourism

2.3. Relationship Between Segmentation and Loyalty in Adventure Tourism

2.4. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

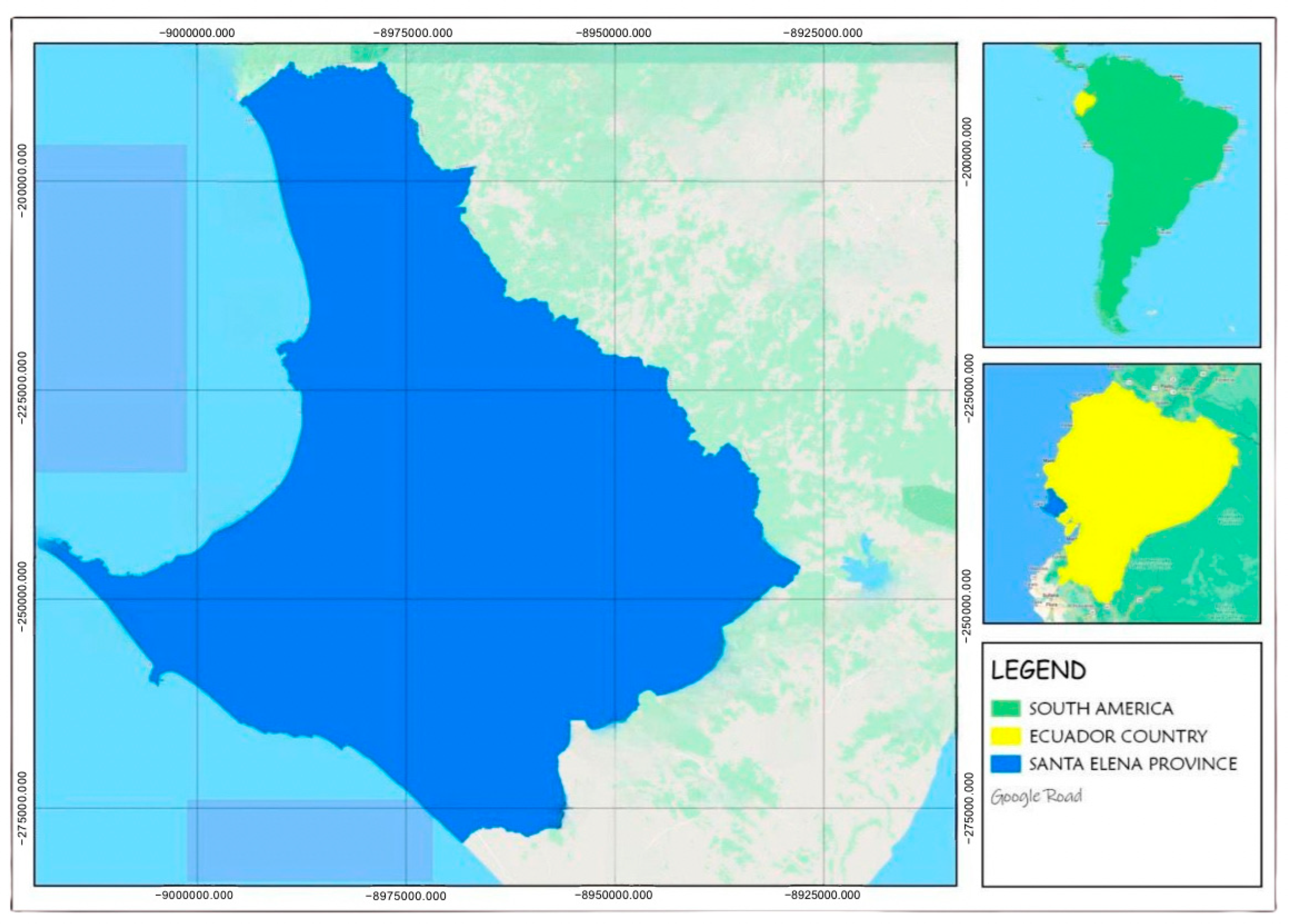

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Questionnaire Design, Data Collection, and Analysis

4. Results

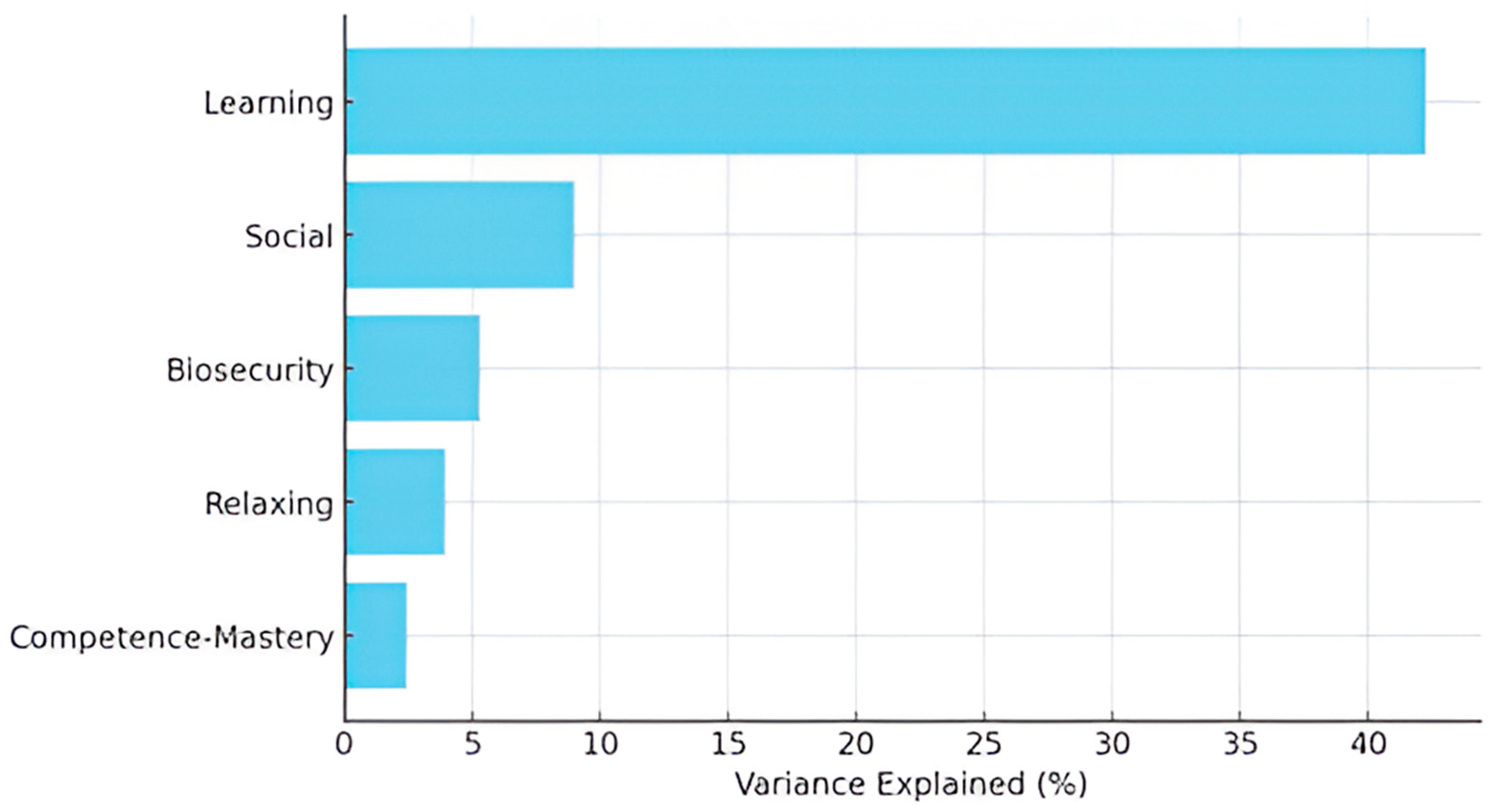

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

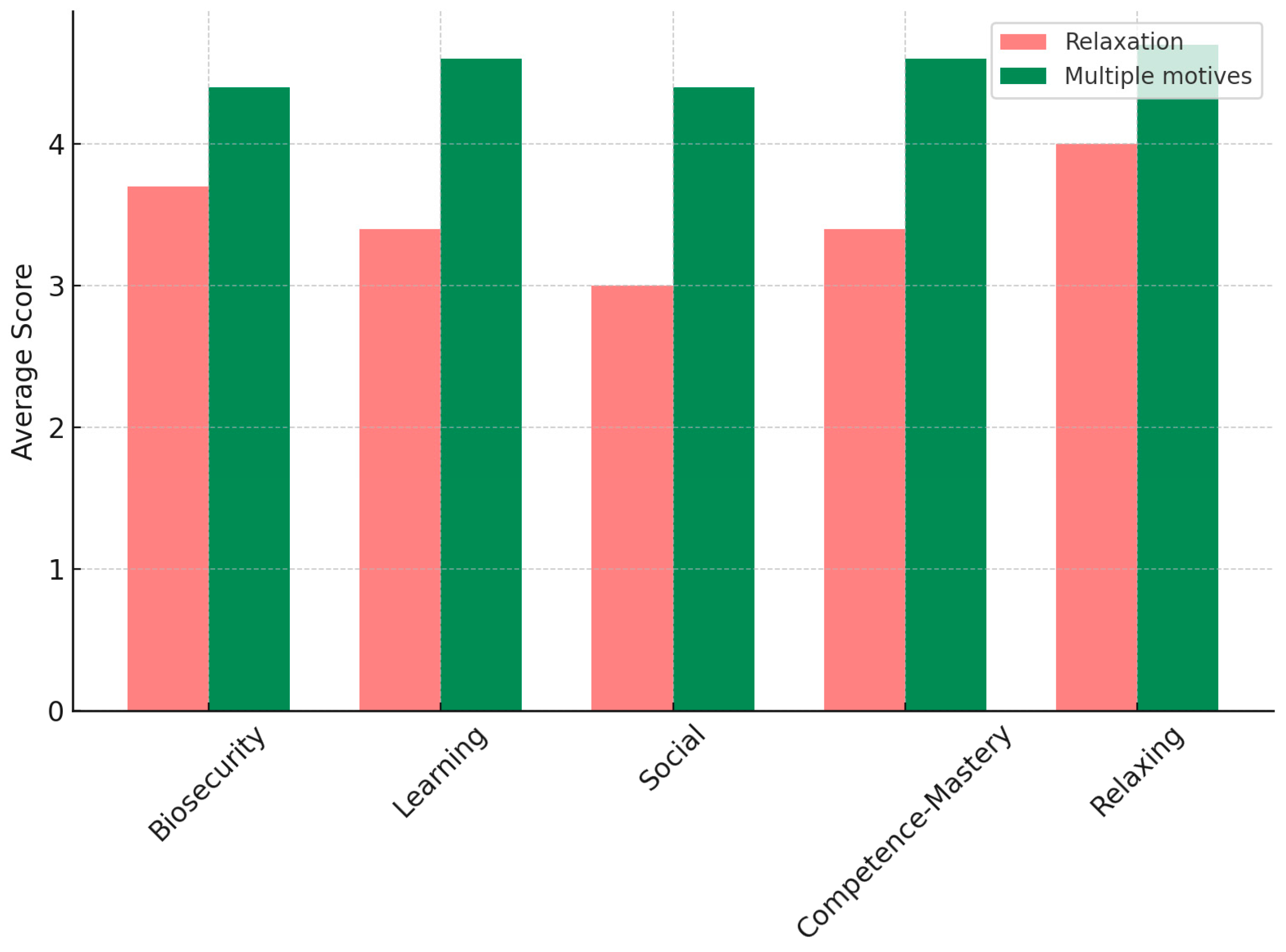

4.2. Segmentation in Adventure Tourism

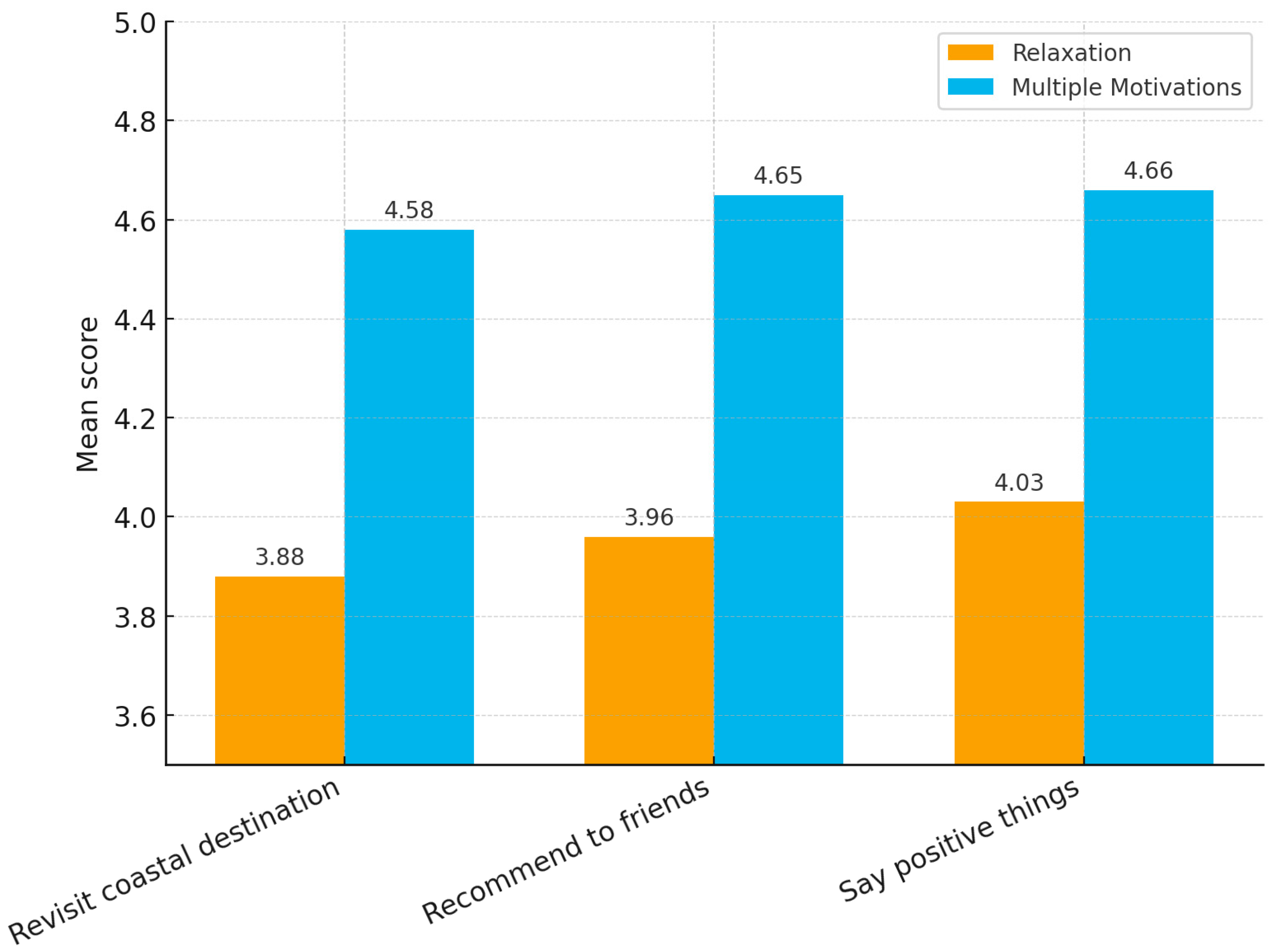

4.3. Segmentation and Loyalty Variables in Adventure Tourism

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Future Market Insights. Adventure Tourism Market Analysis: Growth & Forecast 2025 to 2035. 2025. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/adventure-tourism-market (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Huddart, D.; Stott, T. Adventure tourism: Environmental impacts and management. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 46, 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- Giddy, J.K.; Webb, N.L. The influence of the environment on adventure tourism: From motivations to experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 2132–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O.; Rokenes, A.; Valkonen, J. Is adventure tourism a coherent concept? A review of research approaches on adventure tourism. Ann. Leis. Res. 2016, 21, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaho, Y. Conceptualizing the adventure tourist as a cross-boundary learner. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Beaumont, N. Destination Segmentation: A Recommended Two-Step Approach. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Tolkach, D.; Eka Mahadewi, N.M.; Byomantara, D.G.N. Choosing the Optimal Segmentation Technique to Understand Tourist Behaviour. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laškarin Ažić, M.; Suštar, N. Loyalty to holiday style: Motivational determinants. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessel, K.; Kościółek, S.; Wszendybył-Skulska, E.; Kopera, S. Benefit segmentation in the tourist accommodation market based on eWOM attribute ratings. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2021, 23, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kim, H.; Buning, R.J.; Harada, M. Adventure tourism motivation and destination loyalty: A comparison of decision and non-decision makers. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Fang, Y.H.; Chang, Y.P.; Kuo, C.Y. Exploring motivation via three-stage travel experience: How to capture the hearts of Taiwanese family-oriented cruise tourists. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yu, H. Exploring How Tourist Engagement Affects Destination Loyalty: The Intermediary Role of Value and Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, A.N.; Foroughi, B.; Choong, Y.O. Tourists’ Satisfaction, Experience, and Revisit Intention for Wellness Tourism: E Word-of-Mouth as the Mediator. Sage Open. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Talavera, A. Turismo, un objeto de estudio para la antropología social. Disparidades Rev. Antropol. 2020, 75, e001a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Tarabó, A.E.; Leon, M.; Leon, P.; Lazo, G.; Musso, L. Analysis of the Visitor Profile, Perspectives and Tourism Innovation: Case of Santa Elena, Ecuador; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. The reform in thinking. In Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for the New Millenium; Montuori, A., Ed.; Hampton Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K.R.; Matlovičová, K. Polycrisis in the Anthropocene as a Key Research Agenda for Geography: Ontological Delineation and the Shift to a Postdisciplinary Approach. Folia Geogr. 2024, 66, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D. Tourism in the polycrisis: A Horizon 2050 paper. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodness, D. Measuring tourist motivation. Ann. Tour Res. 1994, 21, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Gillariose, J. Revisiting the Push–Pull Tourist Motivation Model: A Theoretical and Empirical Justification for a Reflective–Formative Structure. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Kozak, M.; Del Chiappa, G. Tourism motivation: A complex adaptive system. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Amin, I.; Santos, J.A.C. Tourists’ Motivations to Travel: A Theoretical Perspective on the Existing Literature. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J.; Horner, S. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, R.; Kondasani, R.K.R.; Das, A. Adventure tourism: Current state and future research direction. Tour. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, E.; Whaley, J.E.; Kim, Y. Motivations and Experiences of Whitewater Rafting Tourists on the Ocoee River, USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Y.; Wang, S.H. Motivations of adventure recreation pioneers—A study of Taiwanese white-water kayaking pioneers. Ann. Leis. Res. 2017, 21, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddy, J.K.; Webb, N.L. Environmental attitudes and adventure tourism motivations. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Xiang, Y.; Weber, K.; Liu, Y. Motivation and involvement in adventure tourism activities: A Chinese tourists’ perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Peters, M. Soft adventure motivation: An exploratory study of hiking tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoch, S.; Mata, S.; Devi, V.; Jain, D.; Mata Vaishno, S. Factors determining tourist’s motivation to visit a place for adventure tourism: A systematic review. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2022, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism. 2021. Available online: www.tonnaja.com/Moment/GettyImages (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Pike, S. Destination Marketing: Essentials; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. Market segmentation analysis in tourism: A perspective paper. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. Tourist Behavior: An International Perspective; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kunjuraman, V.; Mohammad, S.H.; Ramachandran, S.; Matthew, N.K.; Shuib, A. Profiling The Segments of Visitors In Adventure Tourism: Comparison Between Visitors By Recreational Sites. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 20, 1076–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. A motivation-based segmentation of holiday tourists participating in white-water rafting. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.H. Classification of Adventure Travelers: Behavior, Decision Making, and Target Markets. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G.; Doran, A.; Cater, C. Routledge International Handbook of Adventure Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisa, D.G.; Parapanos, D.; Heap, T. The Role of Digital Footprints for Destination Competitiveness and Engagement: Utilizing Mobile Technology for Tourist Segmentation Integrating Personality Traits. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.Y.; Morrison, A.M.; O’leary, J.T. Segmenting the Adventure Travel Market by Activities: From the North American Industry Providers’ Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antti Pesonen, J. Information and communications technology and market segmentation in tourism: A review. Tour. Rev. 2013, 68, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduna, L.T.; van Zyl, C. A benefit segmentation framework for a nature-based tourism destination: The case of Kruger, Panorama and Lowveld areas in Mpumalanga Province. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisescu, O.I.; Gică, O.A.; Dorobanțu, M.C. Exploring the Drivers of Visitor Loyalty in the Context of Outdoor Adventure Parks: The Case of Arsenal Park in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, S.D.; Pham, T.P.; Tučková, Z. Tourist Motivation as an Antecedent of Destination and Ecotourism Loyalty. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigolo, V. Investigating the Attractiveness of an Emerging Long-Haul Destination: Implications for Loyalty. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 17, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespestad, M.K.; Lindberg, F.; Mossberg, L. Value in tourist experiences: How nature-based experiential styles influence value in climbing. Tour Stud. 2019, 19, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanji, S.; Desai, S.; Hanji, S.S.; Navalgund, N.; Tapashetti, R.B. Digital Frontiers: Gen-Z’s Adventure Tourism in the Metaverse; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Yang, Q.; Wu, D.; Zou, Y. Optimizing tourism demand forecasting: An exploration of the combination of push-pull theory, big data analysis and tree-based machine learning models. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2025, 42, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Palomino, O.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Minchenkova, L.; Núñez-Naranjo, A.; Minchenkova, A.; Carvache-Franco, W. Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, H.G.; Fatmawati, I.; Nuryakin Suyanto, M. What drives loyalty in sustainable tourism? Escapism and affordability at Central Java’s heritage sites. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC. Censo 2020 | INEC. 2020. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Contreras-Moscol, D.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Vera-Holguin, H.; Carvache-Franco, O. Motivations and Loyalty of the Demand for Adventure Tourism as Sustainable Travel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado Provincial de Santa Elena. 2025. Available online: https://www.santaelena.gob.ec/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Factor/Measurement Items | Factors Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning. | 13.89 | 42.24 | 0.928 | |

| To expand my knowledge | 0.883 | |||

| To use my imagination | 0.769 | |||

| To satisfy my curiosity | 0.765 | |||

| To discover new things | 0.755 | |||

| To explore new ideas | 0.753 | |||

| To learn about things around me | 0.733 | |||

| To be creative | 0.648 | |||

| To learn about myself | 0.634 | |||

| Social. | 3.256 | 8.97 | 0.894 | |

| To gain a feeling of belonging | 0.862 | |||

| To gain others’ respect | 0.808 | |||

| To reveal my thoughts, feelings, or physical skills to others | 0.721 | |||

| To be socially competent and skillful | 0.712 | |||

| Reduce speed | 0.636 | |||

| To improve my skill and ability in doing them | 0.514 | |||

| To develop close friendships | 0.444 | |||

| Biosecurity. | 2.040 | 5.29 | 0.906 | |

| To be in a destination with a health guarantee | 0.910 | |||

| To be in a destination with biosecurity protocols | 0.847 | |||

| To be attended by service personnel with biosecurity implements | 0.809 | |||

| To be in accommodations and restaurants disinfected and sterilized | 0.793 | |||

| To visit a destination with distancing in leisure service. | 0.665 | |||

| To be in a destination with physical distancing in adventures tourist activities. | 0.595 | |||

| To visit adventure attractions with enough outdoor space | 0.476 | |||

| Relaxing. | 1.633 | 3.95 | 0.882 | |

| To rest | 0.868 | |||

| To relieve stress and tension | 0.836 | |||

| To relax mentally | 0.758 | |||

| To avoid the hustle and bustle of daily activities | 0.741 | |||

| To relax physically | 0.574 | |||

| Destructure my time | 0.337 | |||

| Competence-Mastery. | 1.097 | 2.43 | 0.910 | |

| To use my physical abilities | 0.890 | |||

| To develop physical fitness | 0.799 | |||

| to keep in shape physically | 0.765 | |||

| To develop physical skills and abilities | 0.725 | |||

| To be active | 0.462 |

| Variable | Relaxation | Multiple Motives |

|---|---|---|

| Biosecurity | ||

| Visit destination with facilities for social distancing | 3.5 | 4.1 |

| Being in a destination with safety and protection | 3.7 | 4.3 |

| Be in a destination with transportation | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| Be in a destination with a health guarantee | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Stay in disinfected accommodations and restaurants | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| Be served by service personnel with safety equipment | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| Be in a destination with enough outdoor space | 4.1 | 4.7 |

| Learning | ||

| Learning about the things around me | 3.4 | 4.6 |

| Satisfy my curiosity | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| Explore new ideas | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| Learn about me | 2.9 | 4.4 |

| Expand my knowledge | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| Discover new things | 3.6 | 4.7 |

| Be creative | 3.1 | 4.5 |

| Use my imagination | 2.9 | 4.5 |

| Social | ||

| Develop close friendships | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| Revealing thoughts, feelings, or physical abilities to others | 2.4 | 4.0 |

| Be socially competent and skilled | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| Gain a sense of belonging | 2.7 | 4.1 |

| Gain respect from others | 2.2 | 3.8 |

| Improve my ability to make them | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| Be active | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| Competence-Mastery | ||

| Develop physical skills and abilities | 3.4 | 4.6 |

| Stay physically fit | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| Use my physical abilities | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| Develop physical fitness | 3.2 | 4.4 |

| Meet new friends | 2.5 | 3.8 |

| Relaxing | ||

| Relax physically | 3.7 | 4.6 |

| Relax mentally | 4.0 | 4.8 |

| Avoid the hustle and bustle of daily activities | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| Rest | 4.0 | 4.7 |

| Relieve stress and tension | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| Deconstructing my time | 3.4 | 4.4 |

| Variable | Relaxation | Multiple Motives | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|

| I intend to revisit a coastal destination | 3.88 | 4.58 | p < 0.05 |

| I intend to recommend that my friends visit a coastal destination | 3.96 | 4.65 | p < 0.05 |

| When I talk about coastal destinations after the visit, I will say positive things. | 4.03 | 4.66 | p < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Palomino-Flores, P.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Torres-Naranjo, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Alejandro-Lindao, M. Demand Segmentation for Sustainable Adventure Destination Management: A Study of Santa Elena, Ecuador. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209039

Orden-Mejía M, Carvache-Franco M, Palomino-Flores P, Carvache-Franco O, Torres-Naranjo M, Carvache-Franco W, Alejandro-Lindao M. Demand Segmentation for Sustainable Adventure Destination Management: A Study of Santa Elena, Ecuador. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209039

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrden-Mejía, Miguel, Mauricio Carvache-Franco, Paola Palomino-Flores, Orly Carvache-Franco, Mónica Torres-Naranjo, Wilmer Carvache-Franco, and María Alejandro-Lindao. 2025. "Demand Segmentation for Sustainable Adventure Destination Management: A Study of Santa Elena, Ecuador" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209039

APA StyleOrden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, M., Palomino-Flores, P., Carvache-Franco, O., Torres-Naranjo, M., Carvache-Franco, W., & Alejandro-Lindao, M. (2025). Demand Segmentation for Sustainable Adventure Destination Management: A Study of Santa Elena, Ecuador. Sustainability, 17(20), 9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209039