Shallow Groundwater Hydrochemical Facies, Nitrate Sources and Potential Health Risks in Southern Baoding of North China Using Hydrochemistry and Positive Matrix Factorization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Samples and Method

3.1. Samples

3.2. Positive Matrix Factorization

4. Results

5. Discussion

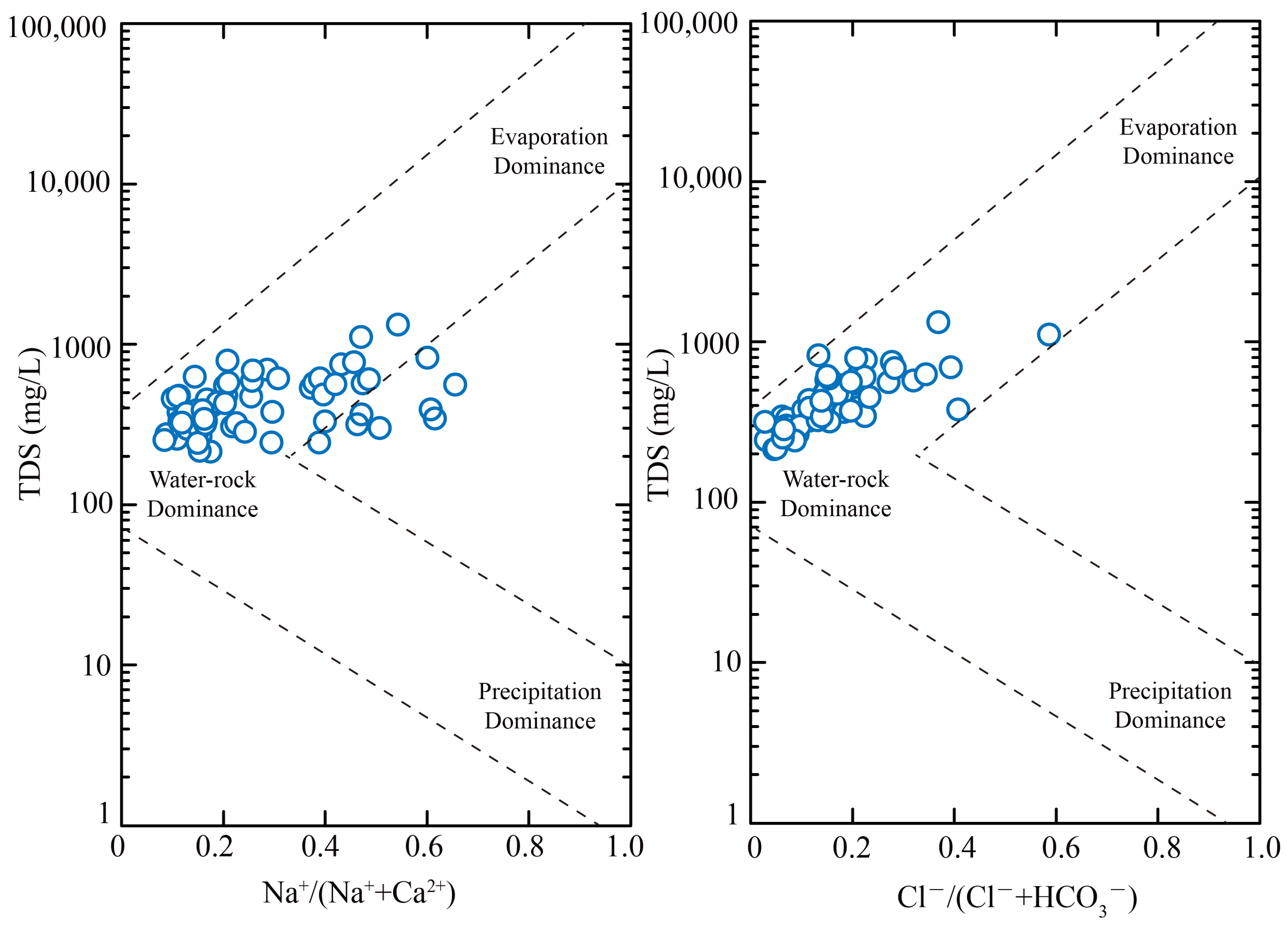

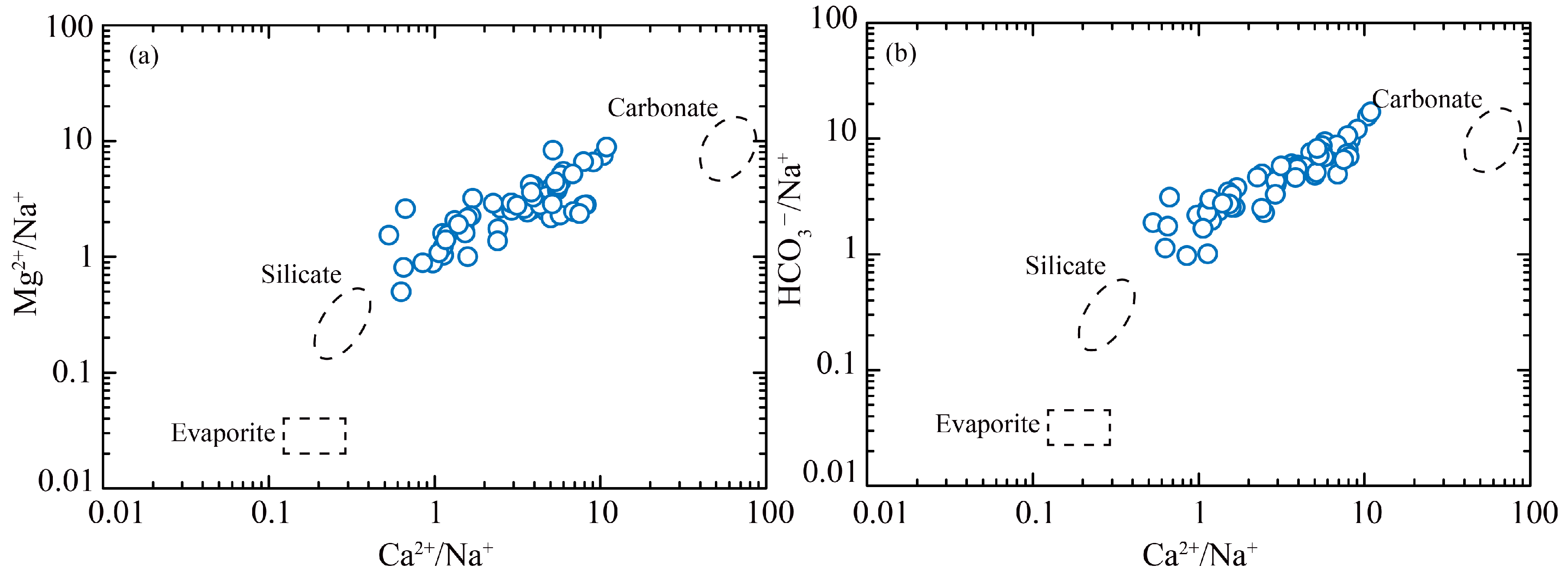

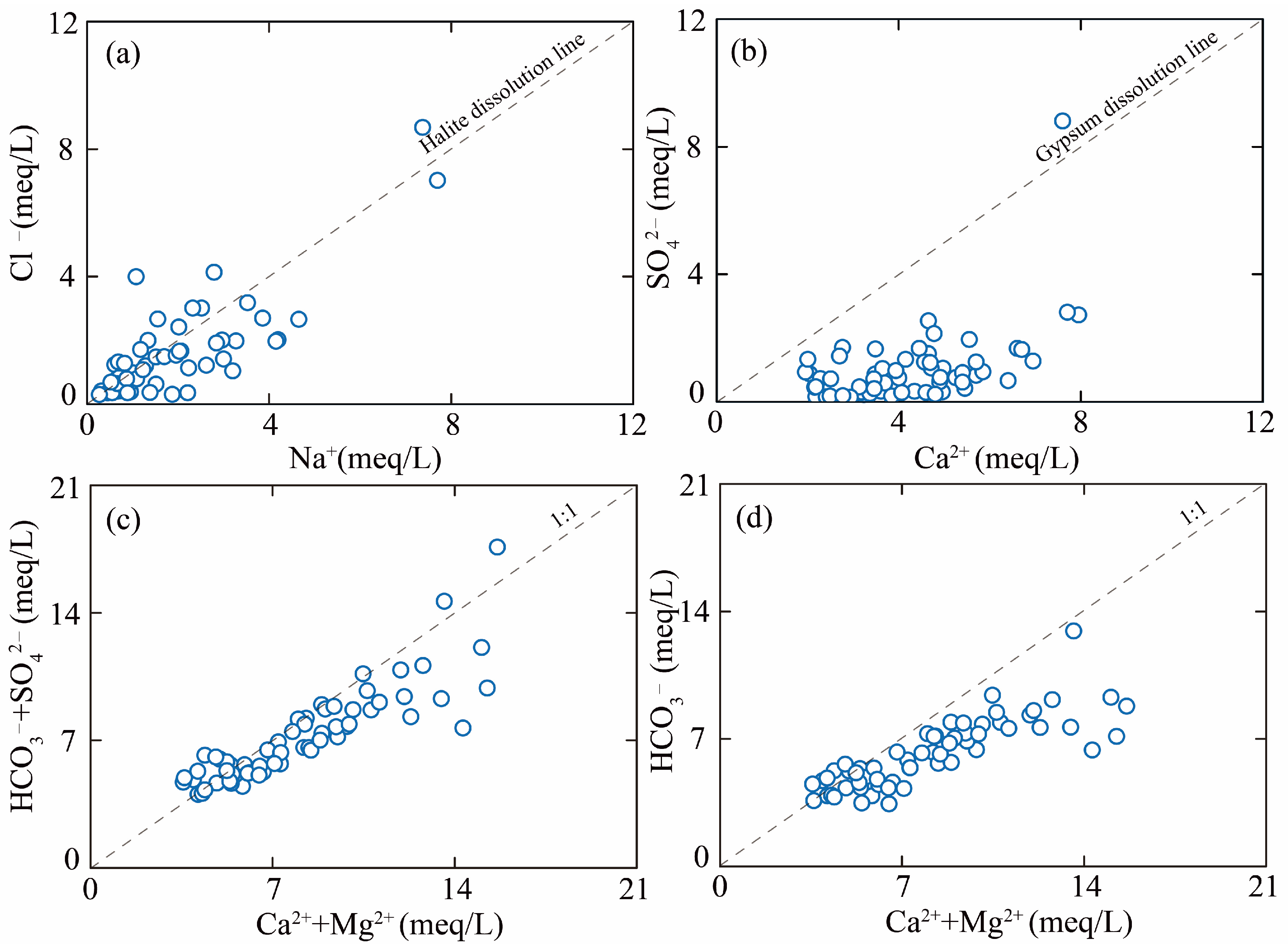

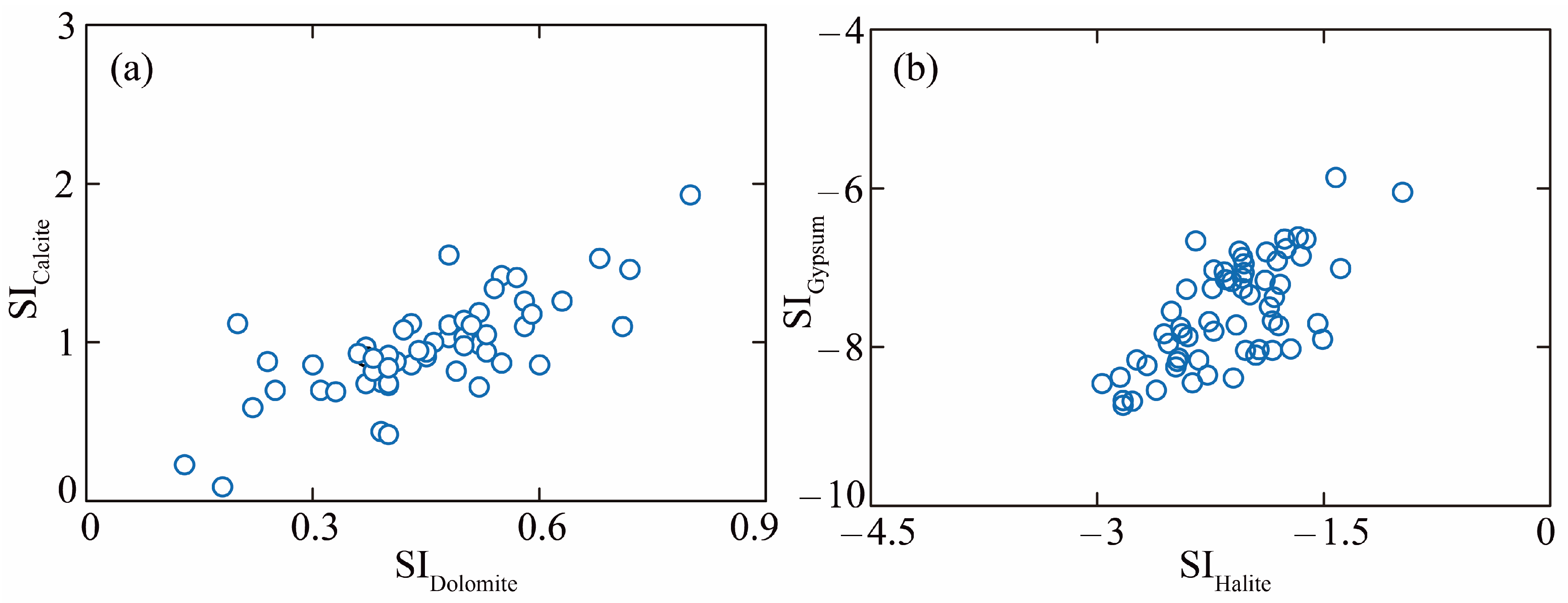

5.1. Hydrochemical Driven Factors

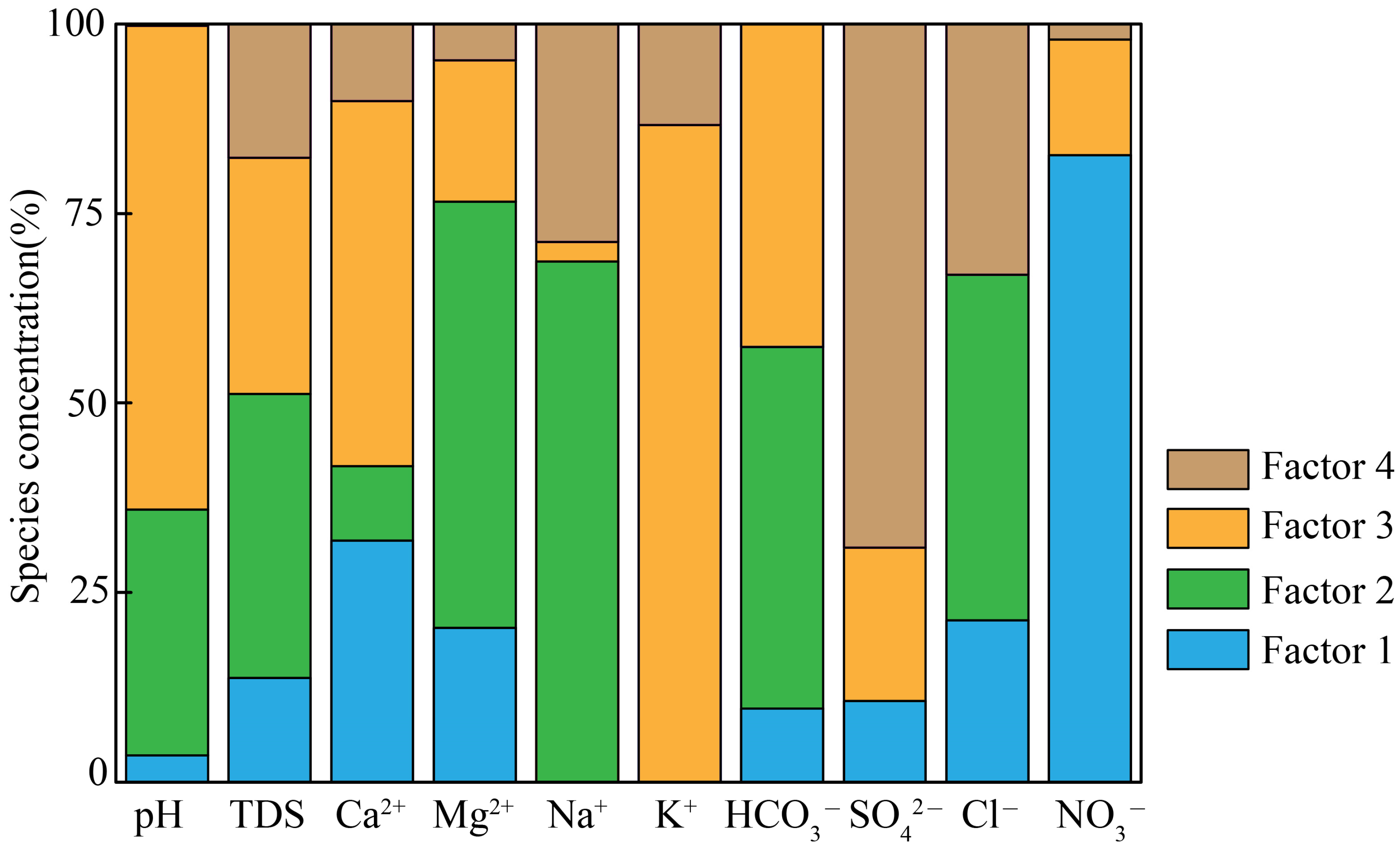

5.2. Source Apportionment by PMF

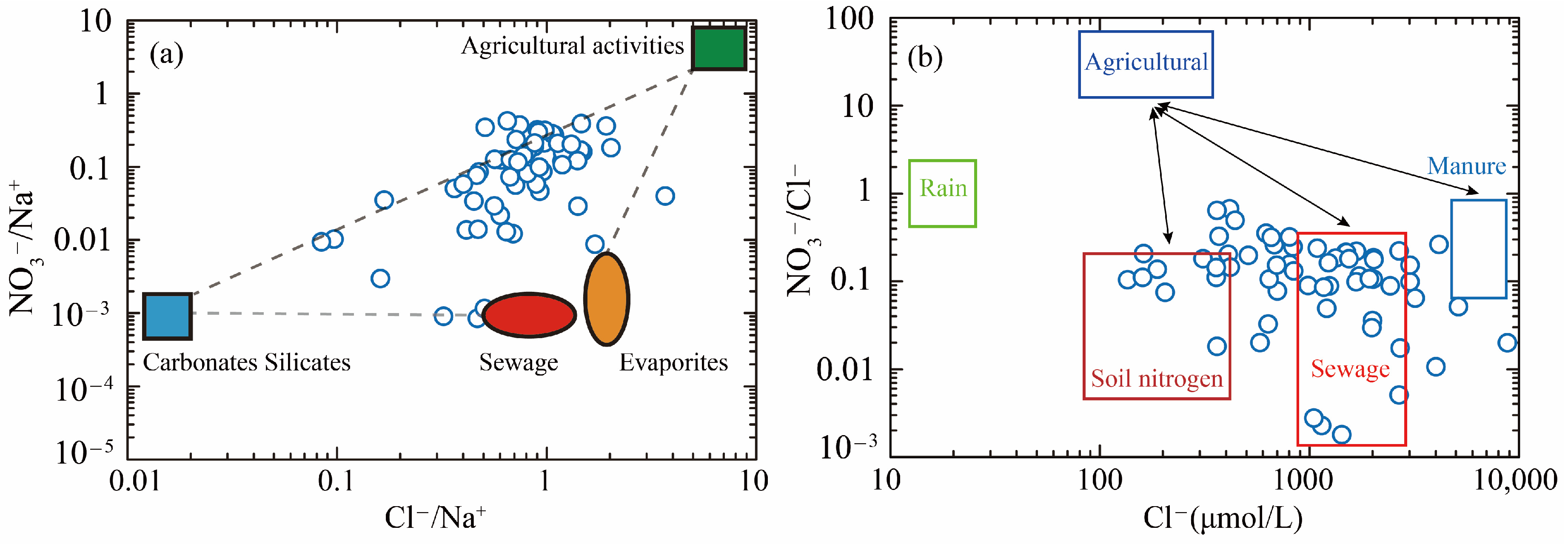

5.3. Identifying Nitrate Sources

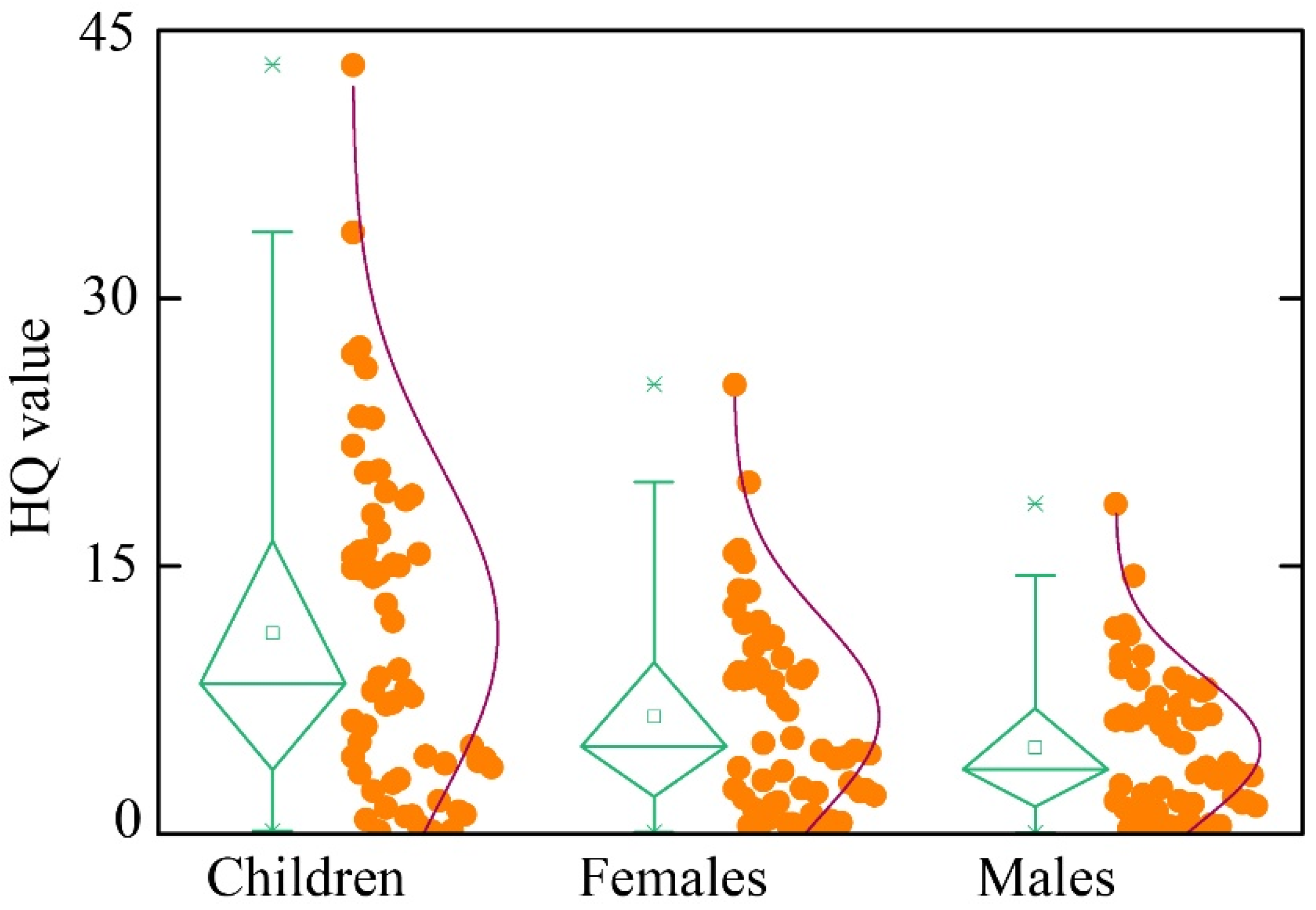

5.4. Human Health Risk Assessment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sridhar, C.N.; Subramani, T.; Kumar, G.R.S.; Soundaranayaki, K. Nitrate pollution index and age wise health risk appraisal for the Pambar River basin in south India. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taloor, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Pir, R.A.; Kumar, K. Appraisal of health risks associated with exposure of fluoride and nitrate contaminated springs in the Doda Kishtwar Ramban (DKR) region of Jammu and Kashmir India. J. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 257, 107380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ai, C.; Xu, X.; Zhai, B.; Wang, Z. Coupling dynamics of soil moisture-nitrate in deep profiles and their relations to groundwater nitrate pollution in irrigated apple production systems. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, P.; Su, F.; Wang, D.; Ren, X. Identification and apportionment of shallow groundwater nitrate pollution in Weining Plain northwest China, using hydrochemical indices, nitrate stable isotopes, and the new Bayesian stable isotope mixing model (MixSIAR). Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khebudkar, A.; Sohoni, M. Estimation of Nitrate Concentration in Groundwater Source Using Zonal Nitrate Balance Method in Male Village of Western Maharashtra. In Geoenvironmental Engineering; Agnihotri, A.K., Reddy, K.R., Bansal, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Wang, G.; Liao, F.; Shi, Z.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Qiao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yan, X.; et al. Spatiotemporal Variation of Groundwater Nitrate Concentration Controlled by Groundwater Flow in a Large Basin: Evidence from Multi-Isotopes (15N, 11B, 18O, and 2H). Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, T.; Kübeck, C.; Quirin, M. Legacy nitrate and trace metal (Mn, Ni, As, Cd, U) pollution in anaerobic groundwater: Quantifying potential health risk from “the other nitrate problem”. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 139, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soula, R.; Chebil, A.; Cetin, M.; Majdoub, R. Spatial analysis and geostatistical characterization of nitrate pollution in Mahdia’s shallow aquifers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 16380–16394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, T.; Hamed, Y.; Hadji, R.; Barbieri, M.; Gentilucci, M.; Rossi, M.; Khalil, R.; Khan, S.D.; Asghar, B.; Al-Omran, A.; et al. Using principal component analysis to distinguish sources of radioactivity and nitrates contamination in Southern Tunisian groundwater samples. J. Geochem. Explor. 2025, 271, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; Liu, Y.-T.; Meng, H.-Q.; Zou, S.; Ma, B.-J.; Feng, Q.-Y. Determining hydrogeological and anthropogenic controls on N pollution in groundwater beneath piedmont alluvial fans using multi-isotope data. J. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 229, 106844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Ye, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Jin, Z. Using PCA-APCS-MLR model and SIAR model combined with multiple isotopes to quantify the nitrate sources in groundwater of Zhuji, East China. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 143, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotiroti, M.; Sacchi, E.; Caschetto, M.; Zanotti, C.; Fumagalli, L.; Biasibetti, M.; Bonomi, T.; Leoni, B. Groundwater and surface water nitrate pollution in an intensively irrigated system: Sources, dynamics and adaptation to climate change. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.-S.; Chen, S.-K.; Chang, L.-F. Evaluation of groundwater vulnerability to nitrate-nitrogen by using probability-based modified DRASTIC models with source and attenuation factors. J. Hydrol. 2025, 655, 132951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Amano, H.; Shinkai, F.; Wakasa, A.; Berndtsson, R. Integrated approach to investigate groundwater nitrate nitrogen pollution and remediation simulation in Shimabara Peninsula, Nagasaki, Japan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.K.; Aitchison-Earl, P.L. Irrigation return flow causing a nitrate hotspot and denitrification imprints in groundwater at Tinwald, New Zealand. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 3583–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, G.; Yang, M. Origins of groundwater nitrate in a typical alluvial-pluvial plain of North China plain: New insights from groundwater age-dating and isotopic fingerprinting. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, I.J.; Chauhan, R.; Kale, S.S.; Gosavi, S.; Rathore, D.; Dwivedi, V.; Singh, S.; Yadav, V.K. Groundwater Nitrate Contamination and its Effect on Human Health: A Review. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Gao, H.; Zhu, M.; Yu, M.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, M.; Su, J.; Xi, B. Spectral and molecular insights into the characteristics of dissolved organic matter in nitrate-contaminated groundwater. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 355, 124202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Howard, K.; Qian, H. Use of multiple isotopic and chemical tracers to identify sources of nitrate in shallow groundwaters along the northern slope of the Qinling Mountains, China. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 113, 104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chow, R.; Su, H.; Han, F.; Li, Z. Multiple isotopes and GIS analyses reveal sources and drivers of nitrate in the Loess Plateau’s groundwater. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 127022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidenfaden, I.K.; Sonnenborg, T.O.; Refsgaard, J.C.; Børgesen, C.D.; Olesen, J.E.; Trolle, D. Are maps of nitrate reduction in groundwater altered by climate and land use changes? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, O.R.; Hosono, T.; Yasumoto, J.; Yasumoto, K.; Song, K.-H.; Maruyama, R.; Iijima, M.; Yasumoto-Hirose, M.; Takada, R.; Hijikawa, K.; et al. Effective use of farmland soil samples for N and O isotopic source fingerprinting of groundwater nitrate contamination in the subsurface dammed limestone aquifer, Southern Okinawa Island, Japan. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, T.; Jia, X.; Zhu, Y.; Shao, M.-A.; Binley, A. A Comparative Study of Conceptual Model Complexity to Describe Water Flow and Nitrate Transport in Deep Unsaturated Loess. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaandorp, V.P.; Broers, H.P.; van der Velde, Y.; Rozemeijer, J.; de Louw, P.G.B. Time lags of nitrate, chloride, and tritium in streams assessed by dynamic groundwater flow tracking in a lowland landscape. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 3691–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Alfio, M.R.; Fiorese, G.D.; Balacco, G. Identification of potential causes of nitrate pollution in three apulian aquifers (Southern Italy). Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, S. Diffusive gradients in thin films for transfer of phosphorus, nitrate and ammonium in lake sediments. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 247, 107175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ye, X.; Du, X. Predictive modeling and analysis of key drivers of groundwater nitrate pollution based on machine learning. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Gao, X.; Jiang, P.; Li, B.; He, N.; Wu, Y.; He, Q.; Cai, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, X. Deep soil desiccation hinders nitrate leaching to groundwater in the global largest apple cultivation area. J. Hydrol. 2024, 637, 131334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Qian, H. Groundwater nitrate response to hydrogeological conditions and socioeconomic load in an agriculture dominated area. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiwal, D.; Jha, M.K.; Singh, V.P.; Mohan, C. Assessment and mapping of groundwater vulnerability to pollution: Current status and challenges. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.J.; Gilmore, T.E.; Nelson, N.; Mittelstet, A.; Böhlke, J.K. Determination of vadose zone and saturated zone nitrate lag times using long-term groundwater monitoring data and statistical machine learning. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Xu, R.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Gan, Y. Source identification of nitrate in groundwater of an agro-pastoral ecotone in a semi-arid zone, northern China: Coupled evidences from MixSIAR model and DOM fluorescence. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 175, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez-Osuna, F.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Ruiz-Fernández, A.C.; García-Hernández, J.; Jara-Marini, M.E.; Bergés-Tiznado, M.E.; Piñón-Gimate, A.; Alonso-Rodríguez, R.; Soto-Jiménez, M.F.; Frías-Espericueta, M.G.; et al. Environmental status of the Gulf of California: A pollution review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 166, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Cheng, W.; Ren, M.; Zhu, Y. Chromium(VI) and nitrate removal from groundwater using biochar-assisted zero valent iron autotrophic bioreduction: Enhancing electron transfer efficiency and reducing EPS accumulation. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 364, 125313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Liu, K.; Wan, L. Hydrochemical characteristics and genetic mechanisms of mid-low temperature geothermal fluids in the eastern segment of the Xinquan—Wentang Fault Zone, Jiangxi Province (In Chinese). Acta Geosci. Sin. 2025, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

| pH | TDS | K+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | Mg2+ | HCO3− | SO42− | Cl− | NO3− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | ||

| groundwater | Max | 8.2 | 1330 | 2.9 | 159.0 | 207.0 | 130.0 | 789.0 | 423.0 | 358.0 | 68.0 |

| Min | 7.0 | 215 | 0.2 | 38.9 | 6.2 | 14.9 | 210.0 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 0.2 | |

| Ave | 7.4 | 464 | 1.2 | 84.2 | 41.1 | 46.7 | 377.5 | 49.5 | 52.4 | 10.6 | |

| SD | 0.2 | 209 | 0.6 | 30.4 | 36.7 | 25.6 | 111.7 | 57.5 | 54.8 | 10.8 | |

| CV | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Parameter | Unit | Children | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral reference dose for NO3− (RfDoral) | mg/(kg×day) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Gastrointestinal absorption factor (ABSgi) | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Drinking rate (IR) | L/day | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Exposure frequency (EF) | days/year | 365 | 365 | 365 |

| Exposure duration (ED) | years | 6 | 30 | 30 |

| Average body weight (BW) | kg | 15 | 55 | 75 |

| Average time (AT) | days | 2190 | 10,950 | 10,950 |

| Skin permeability (K) | cm/h | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Contact duration (T) | h/d | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Exposure frequency of daily dermal contact (EV) | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unit conversion factor (CF) | L/cm3 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Skin surface area (Sa) | - | 6597.01 | 15,475.85 | 18,742.36 |

| Average body height (H) | cm | 99.4 | 153.4 | 165.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Fan, C.; Yang, Y.; Ye, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S. Shallow Groundwater Hydrochemical Facies, Nitrate Sources and Potential Health Risks in Southern Baoding of North China Using Hydrochemistry and Positive Matrix Factorization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310834

Zhao Y, Fan C, Yang Y, Ye F, Liu S, Zhang S. Shallow Groundwater Hydrochemical Facies, Nitrate Sources and Potential Health Risks in Southern Baoding of North China Using Hydrochemistry and Positive Matrix Factorization. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310834

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yuchuan, Chengbo Fan, Yang Yang, Fei Ye, Shurui Liu, and Shouchuan Zhang. 2025. "Shallow Groundwater Hydrochemical Facies, Nitrate Sources and Potential Health Risks in Southern Baoding of North China Using Hydrochemistry and Positive Matrix Factorization" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310834

APA StyleZhao, Y., Fan, C., Yang, Y., Ye, F., Liu, S., & Zhang, S. (2025). Shallow Groundwater Hydrochemical Facies, Nitrate Sources and Potential Health Risks in Southern Baoding of North China Using Hydrochemistry and Positive Matrix Factorization. Sustainability, 17(23), 10834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310834