Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages in Henan Province: A Multi-Method Comprehensive Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Kernel Density Estimation

2.3.2. Optimal Parameter GeoDetector

2.3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

2.3.4. Geographically Weighted Regression

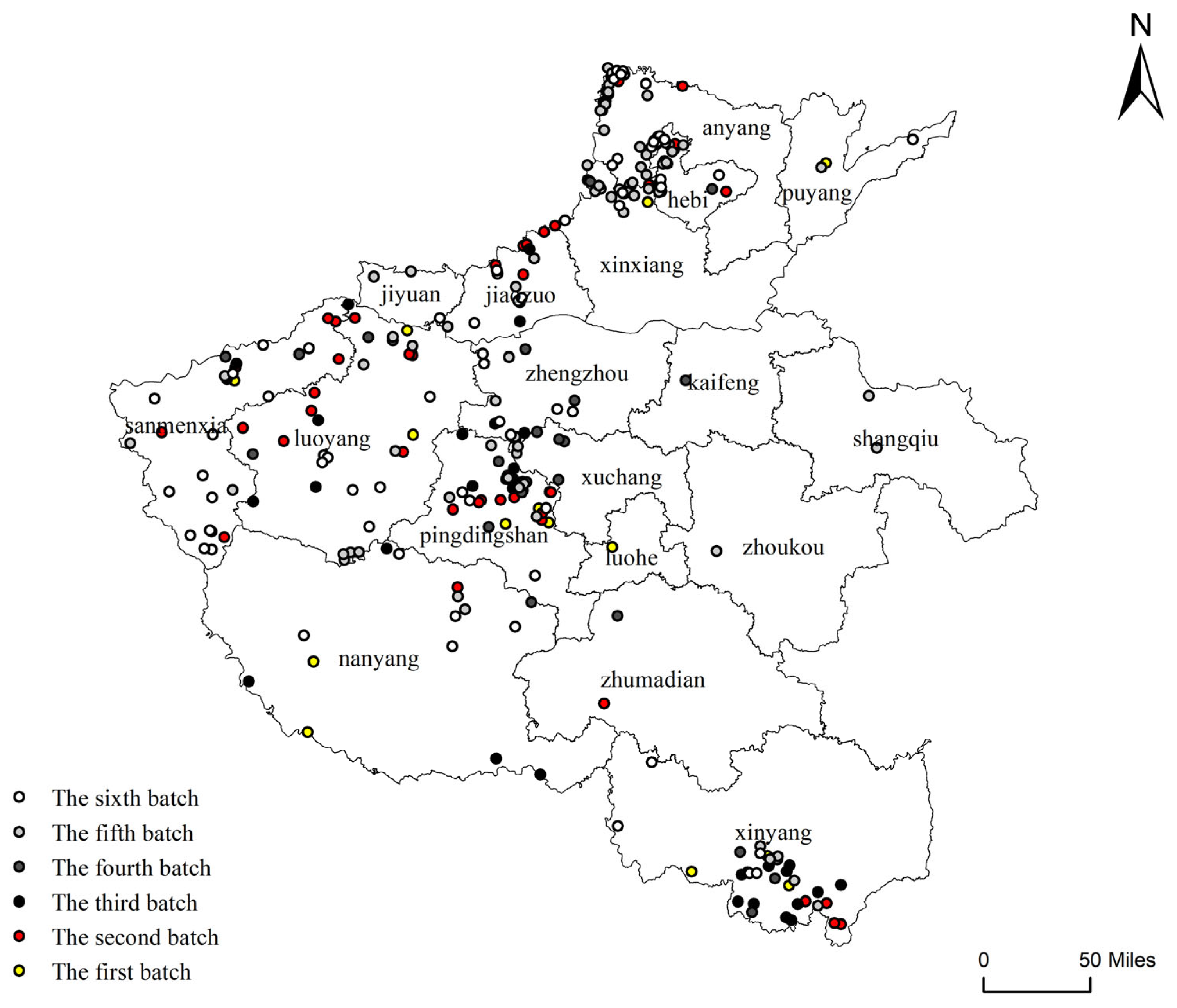

3. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traditional Villages

3.1. Distribution by Administrative Region

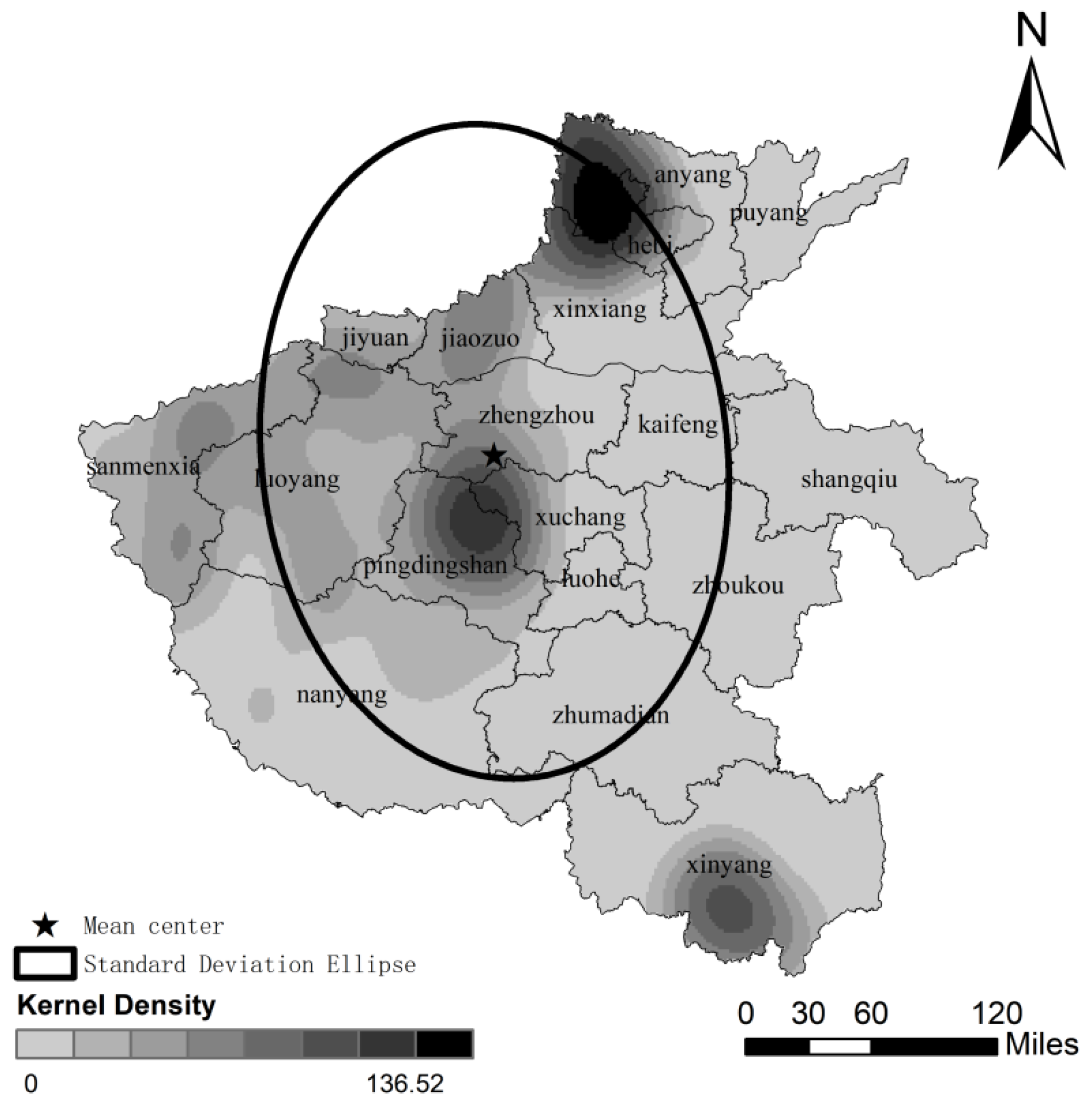

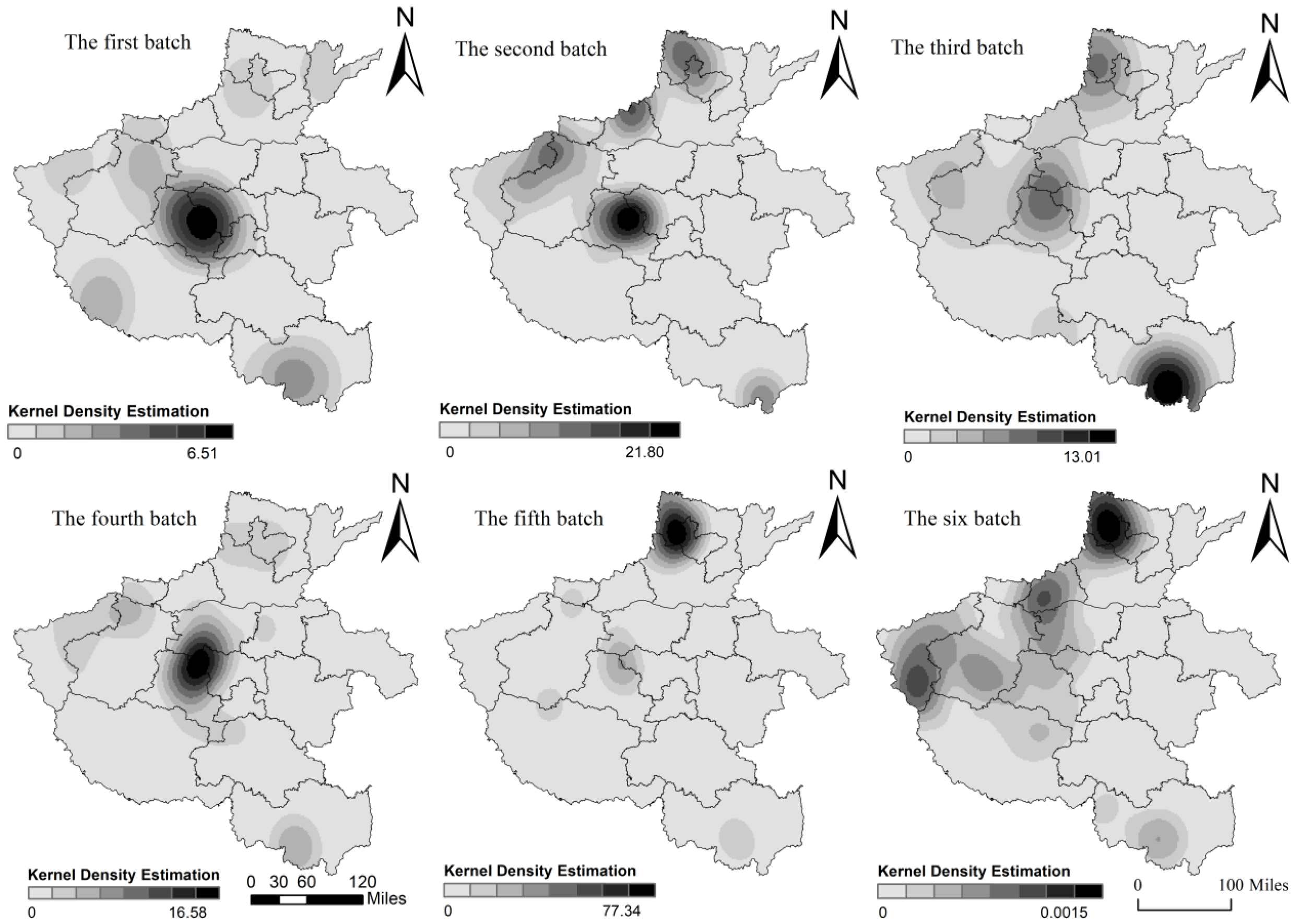

3.2. Kernel Density Distribution Characteristics

4. Analysis of Influencing Factors

4.1. Variable Selection

4.2. Factor Measurement

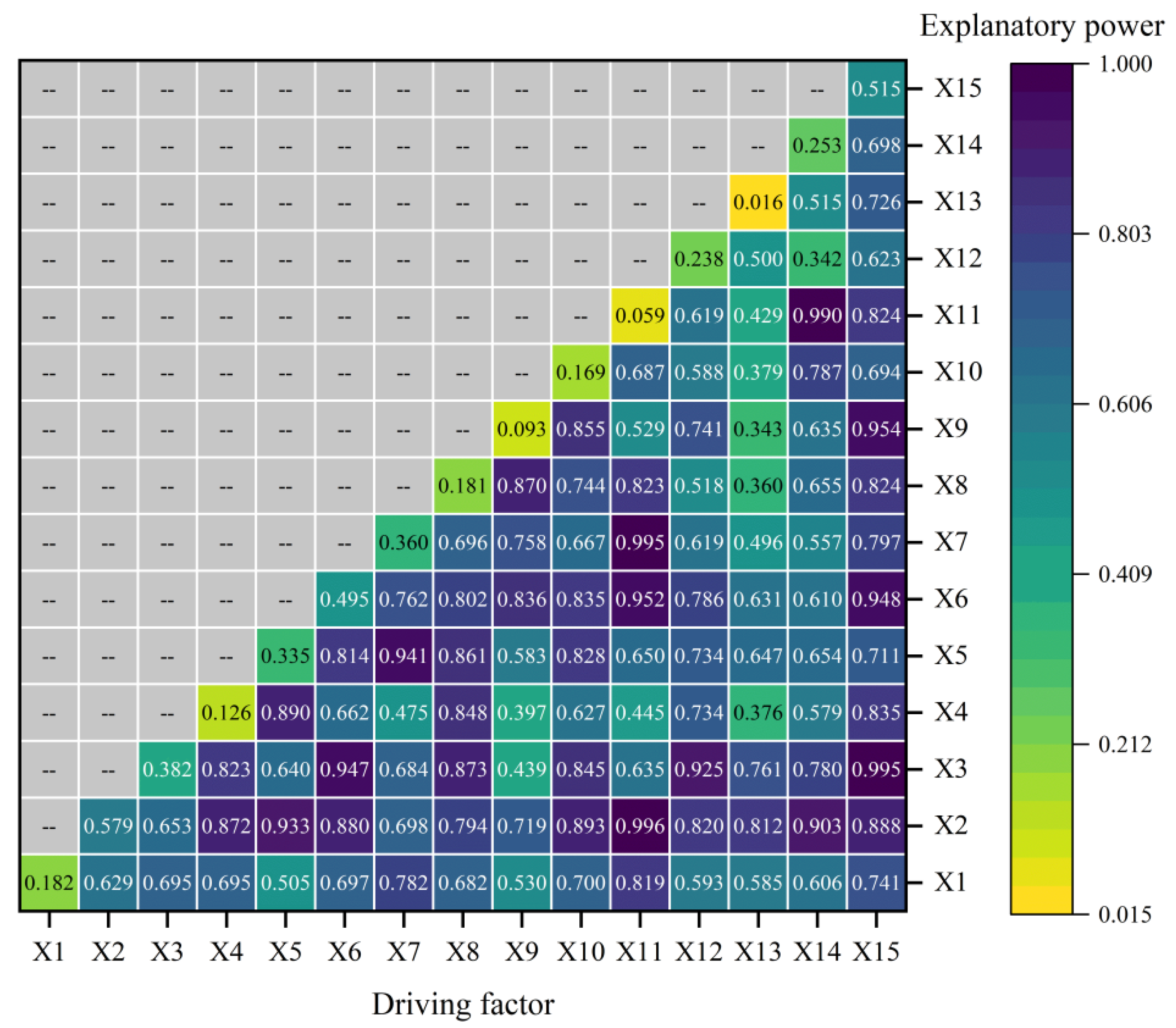

4.3. Interacting Factor Detection

5. Influence Mechanism of Traditional Village Distribution in Henan Province Based on the GWR Model

5.1. Spatial Autocorrelation

5.2. Optimal Model Selection

5.3. GWR Model Regression Results

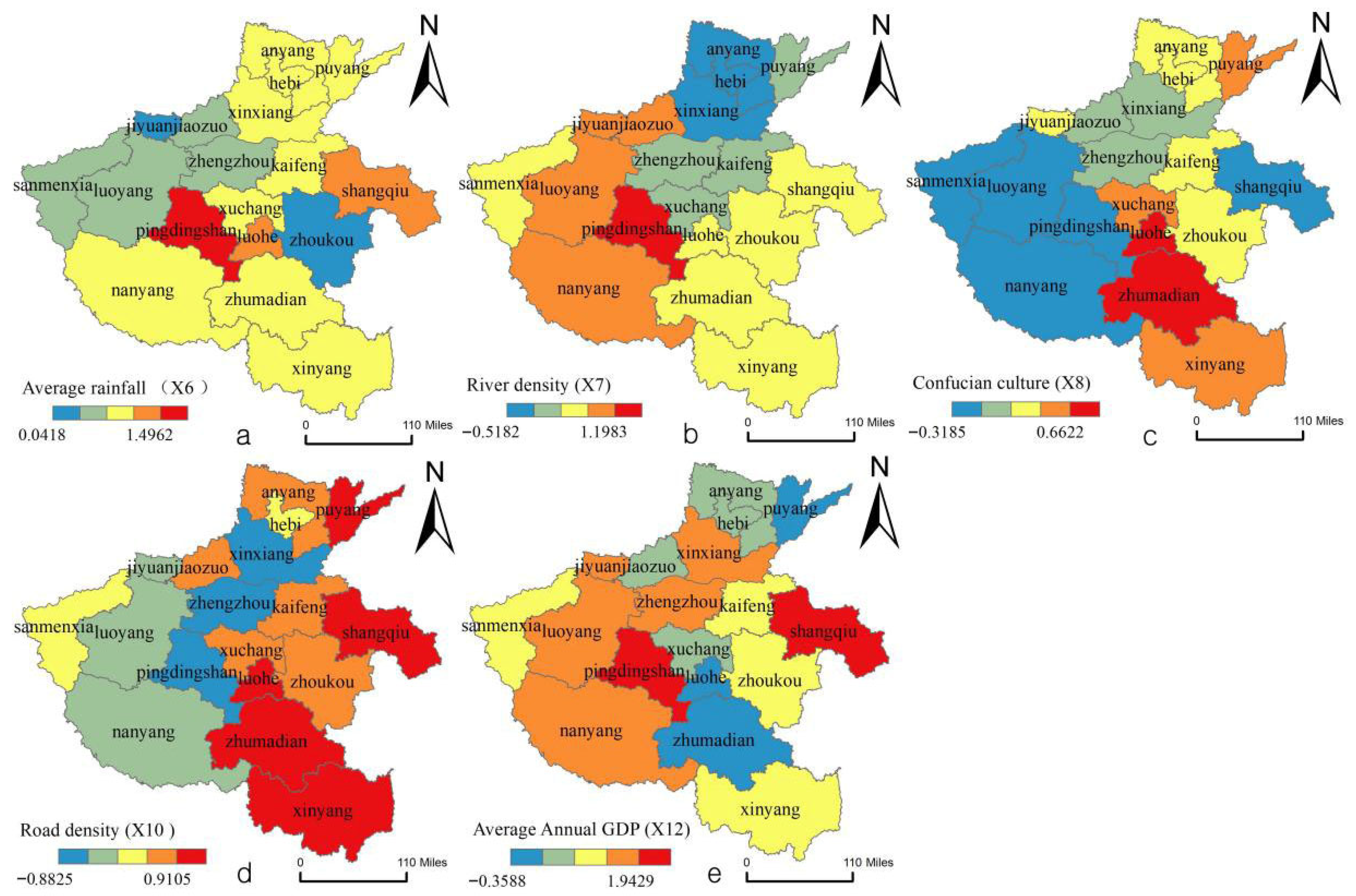

5.3.1. Natural Factors

5.3.2. Cultural Factors

5.3.3. Location and Transportation

5.3.4. Economic Factors

5.3.5. Differentiation Impact Mechanism

6. Discussion

6.1. Critical Interpretation of Results and Comparison with International Research

6.2. Practical Implications from the Perspective of Sustainability

6.3. Research Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, J. The predicament and solution of traditional villages—Also discussing traditional villages as another type of cultural heritage. Folk Cult. Forum 2013, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Michon, G.; Mary, F. Conversion of traditional village gardens and new economic strategies of rural households in the area of Bogor, Indonesia. Agrofor. Syst. 1994, 25, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumadi, K. Tourism development basis in traditional village of Kuta. Int. J. Linguist. Lit. Cult. 2016, 2, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, L. Modeling the relationships between tourism sustainable factor in the traditional village of Pancasari. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 135, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, I.; Saputra, K.; Jayawarsa, A. Regulatory impact assessment analysis in traditional village regulations as strengthening culture in Bali. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of Chinese traditional villages. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, J.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, W. Characteristics and influencing factors of traditional village distribution in China. Land 2022, 11, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Meng, Y.; Yang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Y. Study on spatial distribution characteristics and driving mechanisms of traditional villages in Hainan Island. Areal Res. Dev. 2025, 44, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Jiang, D.; Luan, Y.; Yao, Y. GIS-based spatial differentiation of ethnic minority villages in Guizhou Province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-dimensional hollowing characteristics of traditional villages and its influence mechanism based on the micro-scale: A case study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Q. Influencing factors of traditional village protection and development from the perspective of resilience theory. Land 2022, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Chen, Q.; Gao, H.; Ma, Y. Spatial distribution features and controlling factors of traditional villages in Henan Province. Areal Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Xue, Y.; Shang, C. Spatial distribution analysis and driving factors of traditional villages in Henan province: A comprehensive approach via geospatial techniques and statistical models. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xi, X.; Bi, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Henan Province. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zambom, A.Z.; Dias, R. A review of kernel density estimation with applications to econometrics. Int. Econom. Rev. 2013, 5, 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdont, C.; Fotheringham, S.; Charlton, M. Geographically weighted regression: Modelling spatial non-stationarity. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D Stat. 1998, 47, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Bian, J.; Zeng, J.; Liu, Z. Identifying the spatial differentiation factors of traditional villages in China. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, G.; Bian, J.; Zeng, J.; Liu, Z. Spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the Yangtze River Basin: A Geodetector model. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, G.; Jiang, C.; Bai, J. Differentiation of spatial morphology of rural settlements from an ethnic cultural perspective on the Northeast Tibetan Plateau, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Lee, J.; Ye, X. Spatiotemporal evolution of specialized villages and rural development: A case study of Henan province, China. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2016, 106, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K.; McChesney, R.; Munroe, D.K.; Irwin, E.G. Spatial characteristics of exurban settlement pattern in the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M. Early Chinese Village Patterns in Terms of the Origin of Civilization in China. Soc. Sci. China 2021, 42, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F. How are historical villages changed? A systematic literature review on European and Chinese cultural heritage preservation practices in rural areas. Land 2022, 11, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban regeneration between cultural heritage preservation and revitalization: Experiences with a decision support tool in eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, S.; Knippschild, R.; Battis-Schinker, E.; Knoop, B. Linking Cultural Built Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development: Insights into Strategic Development Recommendations for the German-Polish Border Region. disP-Plan. Rev. 2022, 58, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Count | Proportion | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pingdingshan | 37 | 13.45% | 1 |

| Xinyang | 34 | 12.36% | 2 |

| Luoyang | 34 | 12.36% | 2 |

| Anyang | 33 | 12.00% | 4 |

| Sanmenxia | 30 | 10.91% | 5 |

| Hebi | 29 | 10.55% | 6 |

| Jiaozuo | 18 | 6.55% | 7 |

| Xinxiang | 16 | 5.82% | 8 |

| Nanyang | 14 | 5.10% | 9 |

| Zhengzhou | 12 | 4.36% | 10 |

| Xuchang | 6 | 2.18% | 11 |

| Puyang | 3 | 1.09% | 12 |

| Shangqiu | 2 | 0.73% | 13 |

| Jiyuan | 2 | 0.73% | 13 |

| Zhumadian | 2 | 0.73% | 13 |

| Zhoukou | 1 | 0.36% | 16 |

| Luohe | 1 | 0.36% | 16 |

| Kaifeng | 1 | 0.36% | 16 |

| Indicator | Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Traditional Village Concentration (Y) | |

| Independent Variable | Natural Environment | Average Altitude (X1) |

| Average Slope (X2) | ||

| Average Elevation (X3) | ||

| Average Temperature (X4) | ||

| Average Sunshine (X5) | ||

| Average Rainfall (X6) | ||

| River Density (X7) | ||

| Historical Culture | Academy Density (X8) | |

| Number of Protected Units (X9) | ||

| Location and Transportation | Road Density (X10) | |

| Distance to Major Cities (X11) | ||

| Socio-Economic | Annual Average GDP (X12) | |

| Population Density (X13) | ||

| Fiscal Revenue (X14) | ||

| Urbanization Rate (X15) |

| Batch | Moran’s I | z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Batch | −0.007 | −0.456 | 0.648 |

| Second Batch | 0.073 | 5.367 | 0.000 |

| Third Batch | 0.094 | 6.484 | 0.002 |

| Fourth Batch | 0.073 | 5.350 | 0.000 |

| Fifth Batch | 0.307 | 22.349 | 0.000 |

| Sixth Batch | 0.104 | 7.520 | 0.000 |

| Evaluation Indicators | OLS | GWR | MGWR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.598 | 0.924 | 0.912 |

| Adjust R2 | 0.574 | 0.909 | 0.896 |

| AICc | 188.818 | 63.391 | 72.818 |

| Residual Squares | 36.204 | 6.823 | 7.884 |

| Log-likelihood | 185.452 | −11.624 | −18.129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, M.; Kim, J.-E. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages in Henan Province: A Multi-Method Comprehensive Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310825

Song M, Kim J-E. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages in Henan Province: A Multi-Method Comprehensive Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310825

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Mengru, and Ji-Eun Kim. 2025. "Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages in Henan Province: A Multi-Method Comprehensive Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310825

APA StyleSong, M., & Kim, J.-E. (2025). Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages in Henan Province: A Multi-Method Comprehensive Analysis. Sustainability, 17(23), 10825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310825