Study on the Matching Analysis of Urban Population–Land Spatial Distribution and the Influencing Factors of Multinomial Logistic Classification in Xinjiang

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

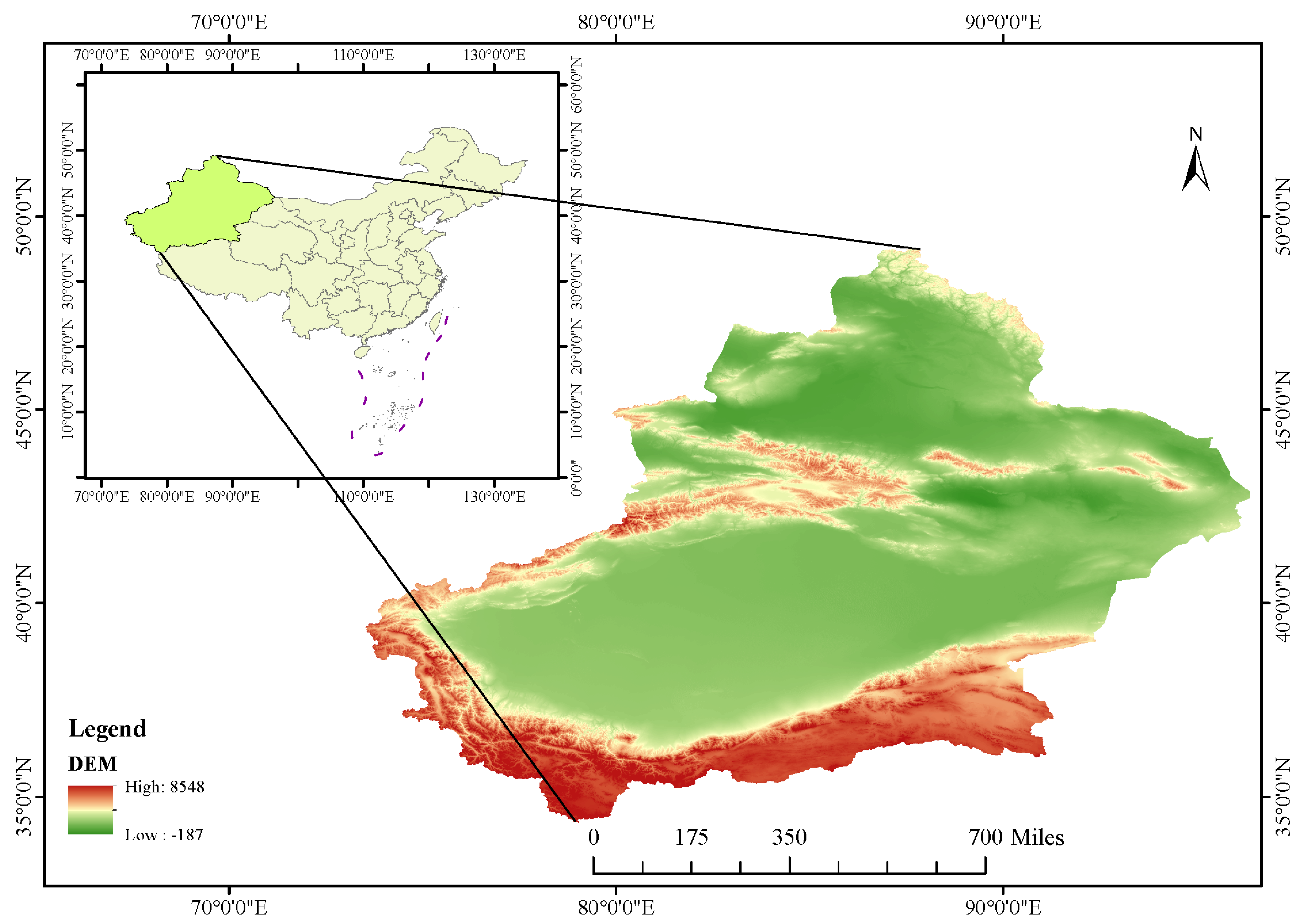

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Construction of the Evaluation System and Selection of Influencing Factors

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Spatial Matching Evaluation Model

2.5. Classification of County-Level Types Based on the Human–Land Matching Relationship

2.6. Multinomial Logistic Regression Model

3. Results Analysis

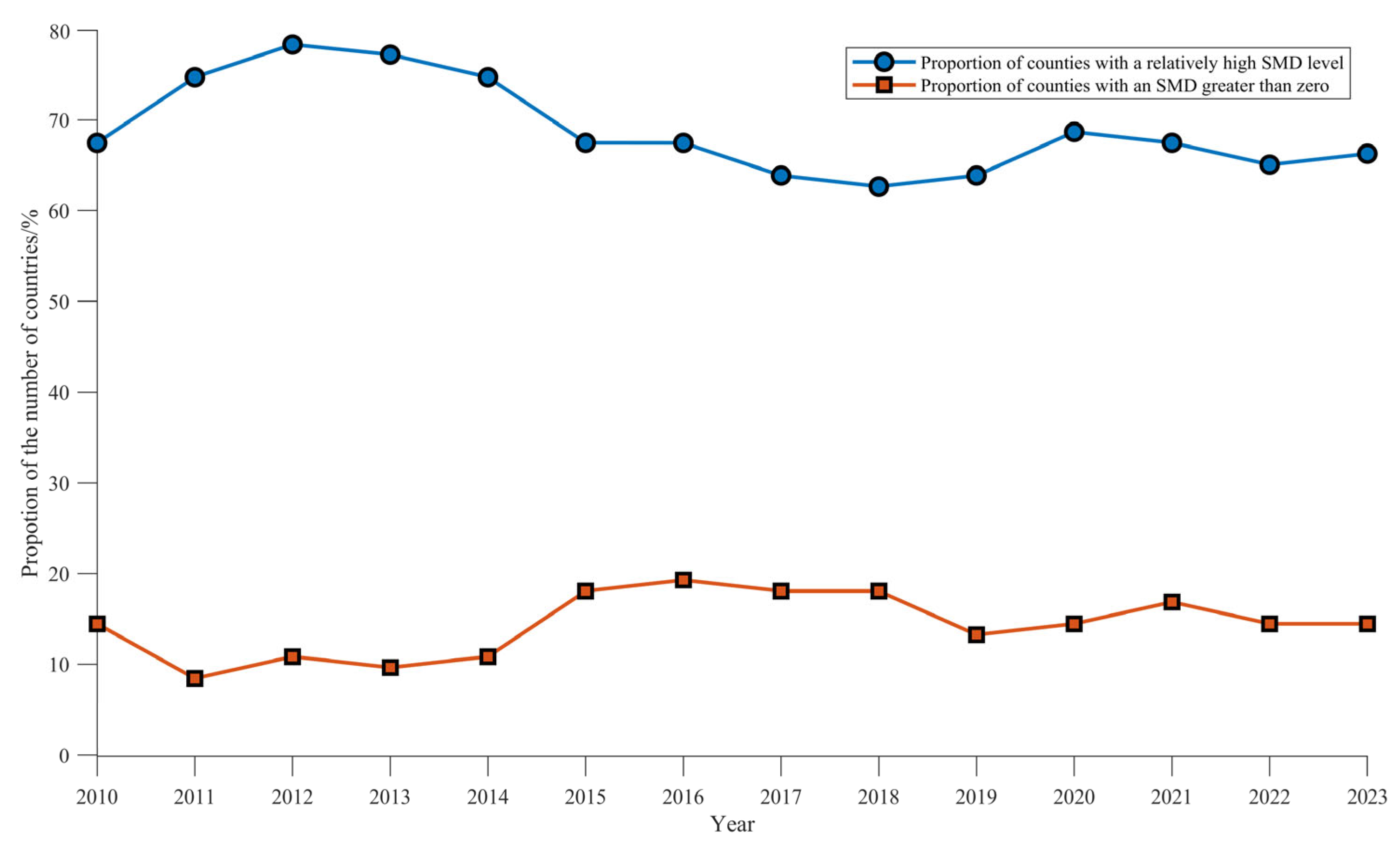

3.1. Matching Pattern of Total Quantity and Increase in Human–Land Matching Relationship

3.1.1. Matching Status of Total Quantity at Time Points

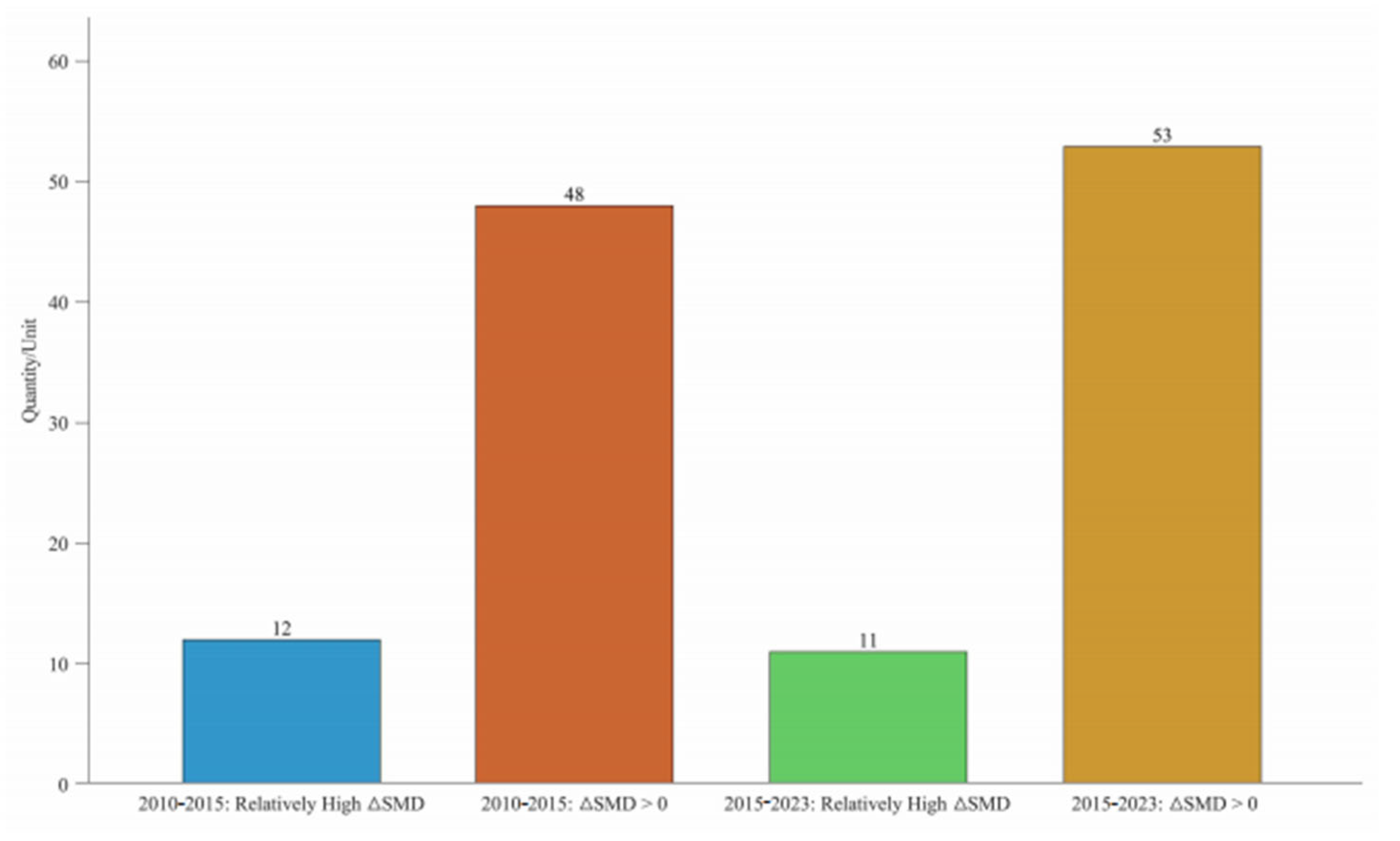

3.1.2. Matching Status of Incremental Changes in Time Periods

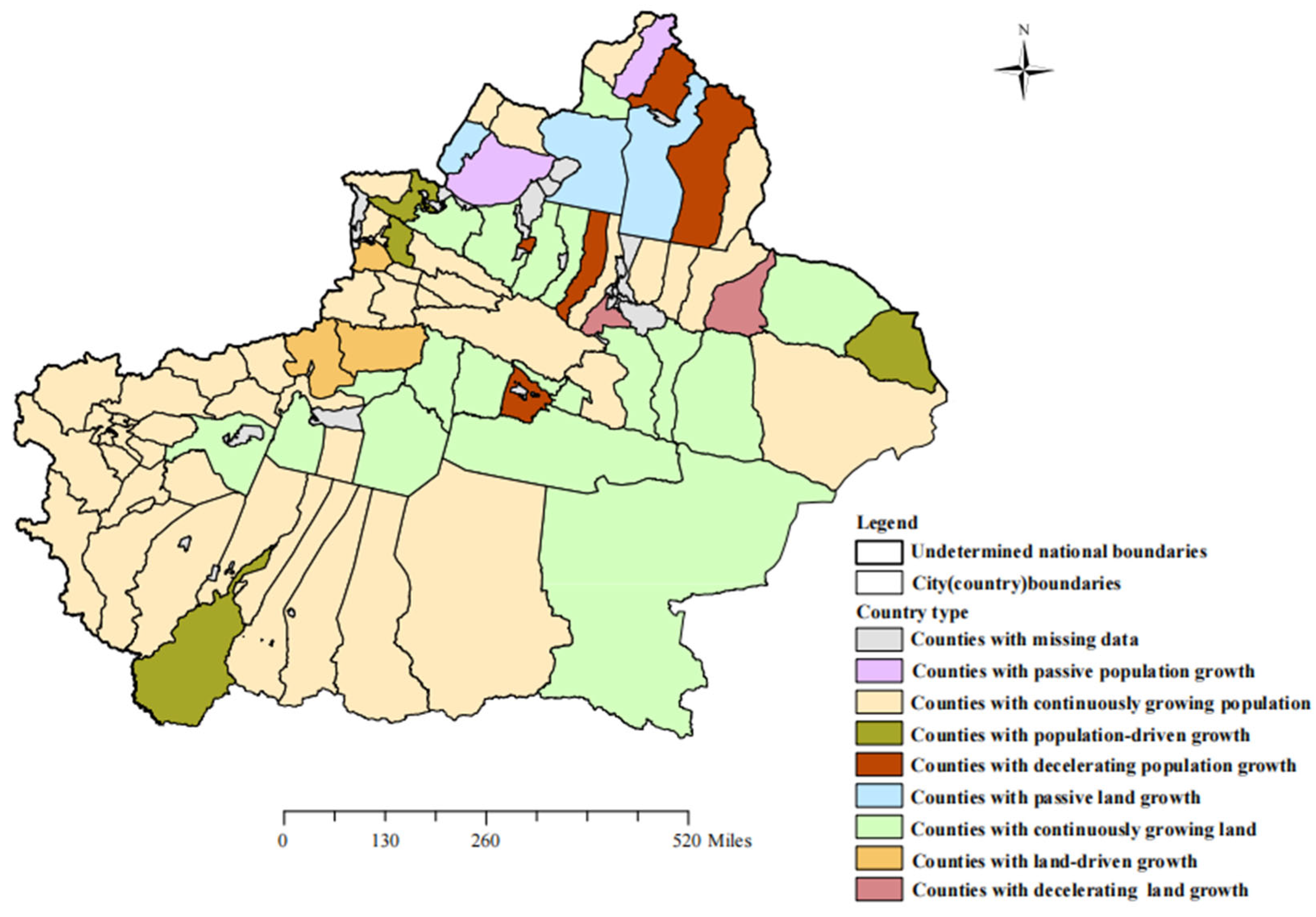

3.2. Distribution Pattern of County Types

3.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Mechanisms of Formation for Different County Types

3.3.1. Model Validation

3.3.2. Mechanistic Analysis of Influencing Factors

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations and Prospects

5.1. Recommendations

5.2. Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.Y.; Bao, W.K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of urban-rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Chen, X. Identification of urban-rural integration types in China–an unsupervised machine learning approach. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cheng, S.; Gao, Y. A visibility-based approach to manage the vertical urban development and maintain visual sustainability of urban mountain landscapes: A case of Mufu Mountain in Nanjing, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 51, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hua, C.; Chen, X.L.; Song, M. The spatial impact of population semi-urbanization on sulfur dioxide emissions: Empirical evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, L. Spatio–temporal dynamics and human–land synergistic relationship of urban expansion in Chinese megacities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, H.; Liao, L.; Tu, S.; Li, T. Land use transitions and urban-rural integrated development: Theoretical framework and China’s evidence. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.H.; Paulukonis, E.; Simmons, C.; Russell, M.; Fulford, R.; Harwell, L.; Smith, L. Projecting effects of land use change on human well-being through changes in ecosystem services. Ecol. Model. 2021, 440, 109358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Kong, X.; Jiang, P. Identification of the human-land relationship involved in the urbanization of rural settlements in Wuhan city circle, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, R.; Zheng, X.; Shao, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Tang, Y. Regional differences of urbanization in China and its driving factors. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2018, 61, 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, W.; Li, X. Rapid urbanization and its driving mechanism in the Pan-Third Pole region. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Liang, L.W.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X. Spatiotemporal differentiation and the factors influencing urbanization and ecological environment synergistic effects within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, S.; Marinova, D.; Zhao, D.; Hong, J. Impacts of urbanization and real economic development on CO2 emissions in non-high income countries: Empirical research based on the extended STIRPAT model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Zhu, L. Urban expansion of oasis cities between 1990 and 2007 in Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2010, 17, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, D.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. Urban Spatial Carrying Capacity and Sustainable Urbanization in the Middle-east Section of North Slope of Kunlun Mountains in Xinjiang, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H. Urban–rural income disparity and urbanization: What is the role of spatial distribution of ethnic groups? A case study of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, X.; Sun, B. A model-based analysis of spatio-temporal changes of the urban expansion in arid area of Western China: A case study in North Xinjiang economic zone. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariken, M.; Zhang, F.; Chan, N.W.; Kung, H.T. Coupling coordination analysis and spatio-temporal heterogeneity between urbanization and eco-environment along the Silk Road Economic Belt in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulimiti, M.; Simayi, Z.; Yang, S.; Chai, Z.; Yan, Y. Study of coordinated development of county urbanization in arid areas of China: The case of Xinjiang. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Luo, K.; Wu, C.; Li, S. Study on Spatialization and Spatial Pattern of Population Based on Multi-Source Data—A Case Study of the Urban Agglomeration on the North Slope of Tianshan Mountain in Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. The Rise of Ethnicity under C hina’s Market Reforms. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attané, I.; Courbage, Y. Transitional stages and identity boundaries: The case of ethnic minorities in China. Popul. Environ. 2000, 21, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, M.; Liang, C. Urbanization of county in China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1241–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Cao, X. The characteristics of spatial expansion and driving forces of land urbanization in counties in central China: A case study of Feixi county in Hefei city. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güneralp, B.; Reba, M.; Hales, B.U.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Trends in urban land expansion, density, and land transitions from 1970 to 2010: A global synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, Q.; Bai, Y.; Fang, C. A novel framework to evaluate urban-rural coordinated development: A case study in Shanxi Province, China. Habitat Int. 2024, 144, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Valenzuela, V.; Holl, A. Growth and decline in rural Spain: An exploratory analysis. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, D. Dramatic uneven urbanization of large cities throughout the world in recent decades. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, L.; Wang, S.J.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Spatial path to achieve urban-rural integration development− analytical framework for coupling the linkage and coordination of urban-rural system functions. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Zeng, N.J. The temporal evolution process and spatial differentiation mechanism of urban-rural integration in China. Hum. Geogr. 2025, 40, 101–112+153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.L.; Xia, L. Research on social integration structure and path of floating population based on structural equation model: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Cai, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z.W. Exploring heterogeneous paths of social integration of the floating population in the communities in Guangdong, China. Cities 2025, 163, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C.C.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Jiang, L.Y.; Zhou, H.X.; Yu, H.Y. Social integration, physical and mental health and subjective well-being in the floating population—A moderated mediation analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1167537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Es, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, K.K.; Lin, Z. Liveability and migration intention in Chinese resource-based economies: Findings from seven cities with potential for population shrinkage. Cities 2022, 131, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Gu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z. Research on the economic effect of employment structure change in heterogeneous regions: Evidence from resource-based cities in China. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 6364–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Yen, S.T.; English, B.C. Spatial variation of output-input elasticities: Evidence from Chinese county-level agricultural production data. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2007, 86, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qi, C.; Xue, B.; Yang, Z. Measuring urban–rural integration through the lenses of sustainability and social equity: Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2025, 165, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergunst, P. Social integration: Social integration: Re-socialisation and symbolic boundaries in Dutch rural neighbourhoods. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, M.; Huang, Y. From industry to education-driven urbanization: A welfare transformation of urbanization in Chinese counties. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jiang, C. Analysis of the spatial and temporal characteristics and dynamic effects of urban-rural integration development in the Yangtze River Delta region. Land 2022, 11, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briski, E.; Langrehr, L.; Kotronaki, S.G.; Sidow, A.; Martinez Reyes, C.G.; Geropoulos, A.; Steffen, G.; Theurich, N.; Dickey, J.W.E.; Hütt, J.C.; et al. Urban environments promote adaptation to multiple stressors. Ecol. Lett. 2025, 28, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alola, A.A.; Özkan, O.; Usman, O. Role of non-renewable energy efficiency and renewable energy in driving environmental sustainability in India: Evidence from the load capacity factor hypothesis. Energies 2023, 16, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; He, P.; Gao, X.; Lin, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhou, W.; Deng, O.; Xu, C.; Deng, L. Land use optimization of rural production–living–ecological space at different scales based on the BP–ANN and CLUE–S models. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmick, J.; Feaster, J.C.; Ramirez, A., Jr. The niches of interpersonal media: Relationships in time and space. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.J.; Yu, L.J. A study on the generalised space of urban–rural integration in Beijing suburbs during the present day. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2581–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Yang, S.; Yin, S.G.; Xu, H. The Characteristics and Evolution Models of Urban Construction Land Agglomeration in the Yangtze River Delta under Rapid Urbanization. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 1917–1934. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cui, X.; Li, F. Exploring the multidimensional coordination relationship between population urbanization and land urbanization based on the MDCE model: A case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.J.; Yang, J.X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Gong, J. Urbanization of county in China: Differences and Influencing Factors of Spatial Matching relationship between urban population and urban land. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 92–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, A.F.; Mohammed, S.; Olaluwoye, O.; Farghali, R.A. Handling multicollinearity and outliers in logistic regression using the robust Kibria–Lukman estimator. Axioms 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.; Hué, S.; Hurlin, C.; Tokpavi, S. Machine learning for credit scoring: Improving logistic regression with non-linear decision-tree effects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.J. Solution of a fractional logistic ordinary differential equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 2022, 123, 107568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Yang, B.; Hussey, O. Examining the Land Use and Land Cover Impacts of Highway Capacity Expansions in California Using Remote Sensing Technology. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Shahfahad; Naikoo, M.W.; Talukdar, S.; Parvez, A.; Rahman, A.; Pal, S.; Asgher, S.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Mosavi, A. Analysing process and probability of built-up expansion using machine learning and fuzzy logic in English Bazar, West Bengal. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension Layer | Indicator Layer | Indicator Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Population Integration | Proportion of Rural Non-Agricultural Labor Force (%) | Number of Rural Non-Agricultural Employees/Total Rural Employed Population |

| Ratio of Non-Agricultural to Agricultural Population Density | Non-Agricultural Population Density/Agricultural Population Density | |

| Proportion of Ethnic Minority Population (%) | Ethnic Minority Population/Total Regional Population | |

| Economic Integration | Per Capita GDP (RMB/person) | GDP/Total Regional Population |

| Industrial Output Value Ratio (%) | Added Value of Primary Industry/(Added Value of Secondary Industry + Added Value of Tertiary Industry) | |

| Level of Synchronized Industrial Development (%) | Index of Added Value of Primary Industry/Average of Index of Added Value of Secondary Industry and Index of Added Value of Tertiary Industry | |

| Grain Yield per Hectare (t/hm2) | Total Grain Output/Sown Area of Grain Crops | |

| Proportion of Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry and Fishery (%) | Gross Output Value of Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry and Fishery/Total Regional GDP | |

| Total Agricultural Machinery Power per Unit Area (100,000 kW/km2) | Total Agricultural Machinery Power/Cultivated Land Area | |

| Social Integration | Ratio of Urban to Rural Retail Sales of Consumer Goods (%) | Total Retail Sales of Consumer Goods in Urban Areas/Total Retail Sales of Consumer Goods in Rural Areas |

| Per Capita Savings Deposit Balance of Urban and Rural Residents (RMB/person) | Total Savings Deposits of Urban and Rural Residents/Total Population | |

| Number of Medical Beds per Capita (bed/person) | Total Number of Medical Beds/Total Regional Population | |

| Ecological Integration | Urban–Rural Ecological Greening Rate (%) | Forest Land Area/Total Regional Area |

| Chemical Fertilizer Input Intensity (t/km2) | Chemical Fertilizer Application Amount/Cultivated Land Area | |

| Rural Electricity Consumption (10,000 kWh) | Total Rural Electricity Consumption | |

| Spatial Integration | Urban–Rural Land Allocation Ratio (%) | Sown Area of Crops/Built-Up Area |

| Urban Spatial Expansion Rate (%) | Built-Up Area/Total Regional Area | |

| Informatization Level (%) | Number of Fixed Telephone Subscribers/Permanent Resident Population of the County |

| Parameter Range | Matching Levels |

|---|---|

| SMD ≥ 0.3 | Positive Low |

| 0 ≤ SMD < 0.3 | Positive High |

| −0.3 < SMD < 0 | Negative High |

| SMD ≤ −0.3 | Negative Low |

| Parameter Range | Matching Levels |

|---|---|

| ΔSMD ≥ 0.3 | Positive Low |

| 0 ≤ ΔSMD < 0.3 | Positive High |

| −0.3 < ΔSMD < 0 | Negative High |

| ΔSMD ≤ −0.3 | Negative Low |

| County-Level Type | Initial Period-Process Period-End Period Combination | Terminal Quantitative Relationship | Relationship of Process Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population-Promoted-Growth Type | Negative—Positive—Positive | Urban Population > Urban Land | Urban Population > Urban Land |

| Population-Growth-Slowing Type | Positive—Negative—Positive | Urban Population < Urban Land | |

| Population-Sustained-Growth Type | Positive—Positive—Positive | Urban Population > Urban Land | |

| Population-Passive-Growth Type | Negative—Negative—Positive | Urban Population < Urban Land | |

| Land-Promoted-Growth Type | Positive—Negative—Negative | Urban Population < Urban Land | Urban Population < Urban Land |

| Land-Growth-Slowing Type | Negative—Positive—Negative | Urban Population > Urban Land | |

| Land-Sustained-Growth Type | Negative—Negative—Negative | Urban Population < Urban Land | |

| Land-Passive-Growth Type | Positive—Positive—Negative | Urban Population > Urban Land |

| Population-Promoted-Growth Type | Population-Growth-Slowing Type | Population-Sustained-Growth Type | Population-Passive-Growth Type | Land-Promoted-Growth Type | Land-Growth-Slowing Type | Land-Sustained-Growth Type | Land-Passive-Growth Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of Rural Non-Agricultural Labor Force | 0.632 | −0.66 ** | 0.195 | 0.237 | 0.206 | 0.113 | 0.165 | 0.258 |

| (−0.22) | (−3.579) | (−1.03) | (0.585) | (0.747) | (−0.353) | (0.824) | (−0.711) | |

| Ratio of Non-Agricultural to Agricultural Population Density | 0.348 ** | 0.054 | −0.029 | −0.031 | 0.022 ** | −0.008 | −0.125 | 0.020 * |

| (4.053) | (−0.156) | (−0.084) | (−0.049) | (−3.051) | (−0.013) | (−0.349) | (−1.739) | |

| Proportion of Ethnic Minority Population | −0.417 | 0.157 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.056 | 0.306 | 0.387 * | 0.087 ** |

| (−0.122) | (2.725) | (−2.421) | (−2.766) | (−0.265) | (−1.138) | (1.712) | (−3.219) | |

| Per Capita GDP | 0.665 ** | 0.614 * | −0.395 | 0.114 | 0.448 ** | 0.042 | 0.049 | 0.059 |

| (−4.154) | (−2.047) | (−1.559) | (0.255) | (3.294) | (−0.123) | (0.226) | (0.146 | |

| Industrial Output Value Ratio | 0.413 * | 0.176 ** | −0.105 | 0.368 * | −0.351 | 0.02 | 0.001 ** | 0.211 * |

| (1.729) | (−2.657) | (−0.507) | (−1.767) | (−1.248) | (−0.055) | (4.006) | (−1.844) | |

| Level of Synchronized Industrial Development | 0.191 | −0.086 | −0.064 | 0.04 | 0.188 ** | 0.134 * | 0.414 * | −0.072 |

| (−0.089) | (−0.441) | (−0.410) | (−0.12) | (2.862) | (−1.772) | (−2.086) | (−0.222) | |

| Grain Yield per Hectare | 0.096 | −0.127 | 0.147 ** | 0.357 * | 0.158 | −0.206 | −0.244 ** | 0.246 |

| (−0.04) | (−0.558) | (−2.798) | (−1.778) | (−0.633) | (−0.695) | (−3.247) | (−0.616) | |

| Total Agricultural Machinery Power per Unit Area | −0.332 | −0.241 | 0.194 | −0.212 ** | −0.056 * | 0.500 ** | 0.125 | −0.25 |

| (−0.101) | (−0.930) | (−0.994) | (−2.817) | (−0.179) | (2.341) | (−0.608) | (−0.578) | |

| Ratio of Urban to Rural Retail Sales of Consumer Goods | 0.093 ** | 0.297 * | 0.103 | 0.301 * | 0.214 | −0.304 | 0.109 ** | −0.138 |

| (−3.030) | (−1.693) | (−0.586) | (1.706) | (0.78) | (1.281) | (−2.592) | (−0.384) | |

| Per Capita Savings Deposit Balance of Urban and Rural Residents | 0.722 ** | 0.593 ** | 0.119 | 0.064 | −0.139 | −0.126 ** | −0.199 | 0.163 |

| (−3.162) | (2.872) | (−0.507) | (−0.136) | (−0.393) | (−2.599) | (−0.805) | (0.32) | |

| Number of Medical Beds per Capita | 0.082 ** | 0.156 | 0.244 ** | 0.312 ** | 0.526 * | 0.174 | 0.144 * | 0.051 |

| (2.915) | (−0.838) | (−2.624) | (3.181) | (−1.695) | (−0.618) | (−1.963) | (−0.181) | |

| Urban–Rural Ecological Greening Rate | 0.417 | 0.057 | −0.135 | −0.019 | −0.042 | 0.099 ** | −0.041 | −0.396 |

| (−0.130) | (0.257) | (0.686) | (−0.054) | (−0.178) | (2.369) | (−0.200) | (−0.799) | |

| Chemical Fertilizer Input Intensity | −0.386 | 0.271 | 0.313 * | 0.019 | 0.377 ** | 0.092 | 0.255 ** | 0.514 ** |

| (−0.145) | (−0.785) | (−1.704) | (0.658) | (−2.449) | (1.325) | (−2.371) | (−2.484) | |

| Rural Electricity Consumption | 0.061 ** | −0.286 | −0.077 | 0.053 | −0.28 * | 0.068 | −0.171 | −0.190 |

| (−2.424) | (−1.178) | (−0.382) | (−0.131) | (−3.027) | (−0.189) | (−0.810) | (−0.486) | |

| Urban–Rural Land Allocation Ratio | 0.476 * | 0.011 | −0.163 ** | 0.021 ** | 0.026 | −0.105 | −0.108 ** | 0.034 ** |

| (−1.876) | (−0.017) | (−3.290) | (2.424) | (−0.034) | (−0.119) | (−2.377) | (3.029) | |

| Urban Spatial Expansion Rate | −0.101 ** | 0.183 | −0.163 | −0.228 ** | 0.08 ** | −0.196 * | 0.017 | 0.068 ** |

| (−2.744) | (0.489) | (−0.473) | (−2.357) | (3.175) | (−1.684) | (−0.049) | (−3.122) | |

| Intercept | 0.145 | 0.311 | 2.586 ** | −1.753 ** | −0.379 | −0.819 ** | 1.682 ** | −1.559 ** |

| (−0.023) | (−1.479) | (−15.638) | (−4.291) | (−1.492) | (−2.831) | (−9.696) | (−4.077) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, W.; Ma, Q. Study on the Matching Analysis of Urban Population–Land Spatial Distribution and the Influencing Factors of Multinomial Logistic Classification in Xinjiang. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310822

Hu W, Ma Q. Study on the Matching Analysis of Urban Population–Land Spatial Distribution and the Influencing Factors of Multinomial Logistic Classification in Xinjiang. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310822

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Weixiao, and Qiong Ma. 2025. "Study on the Matching Analysis of Urban Population–Land Spatial Distribution and the Influencing Factors of Multinomial Logistic Classification in Xinjiang" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310822

APA StyleHu, W., & Ma, Q. (2025). Study on the Matching Analysis of Urban Population–Land Spatial Distribution and the Influencing Factors of Multinomial Logistic Classification in Xinjiang. Sustainability, 17(23), 10822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310822