Environmental Impact of Lead-Acid Batteries: A Review of Sustainable Alternatives for Production and Recycling Based on Life Cycle Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

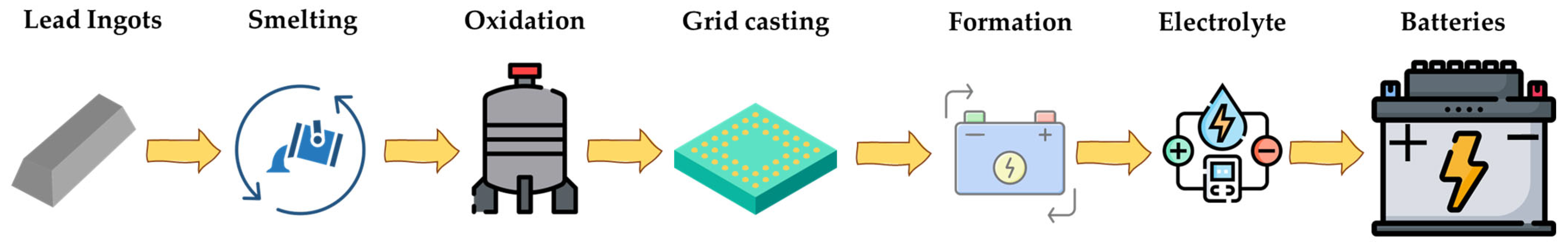

2. LAB Manufacturing Industry

Advances in the LAB Production Industry

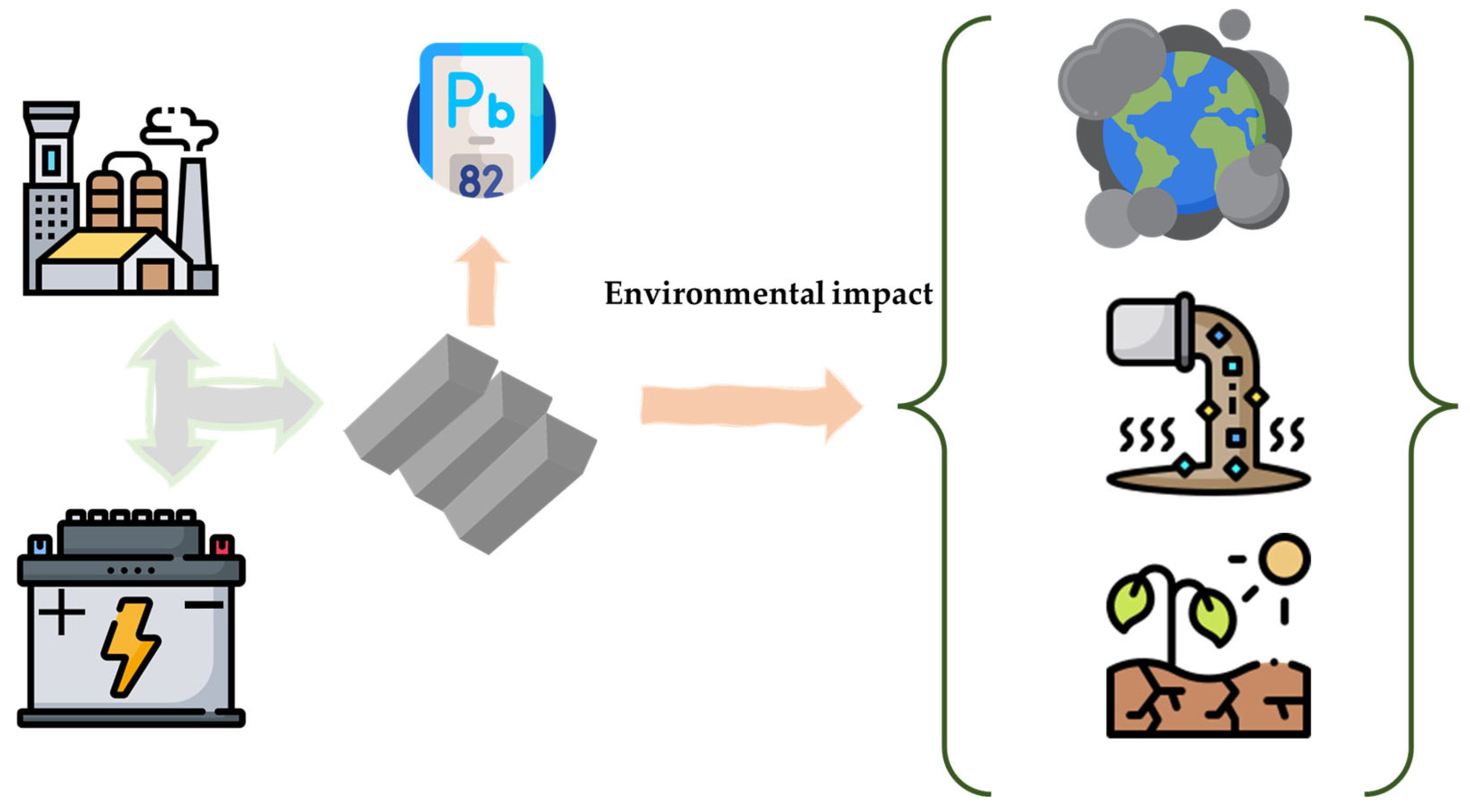

3. Environmental Impact of LAB Production and Use

3.1. Environmental Matrices

3.1.1. Soil

3.1.2. Air

3.1.3. Water

3.2. Human Health

Socioeconomic Factors and Environmental Inequality

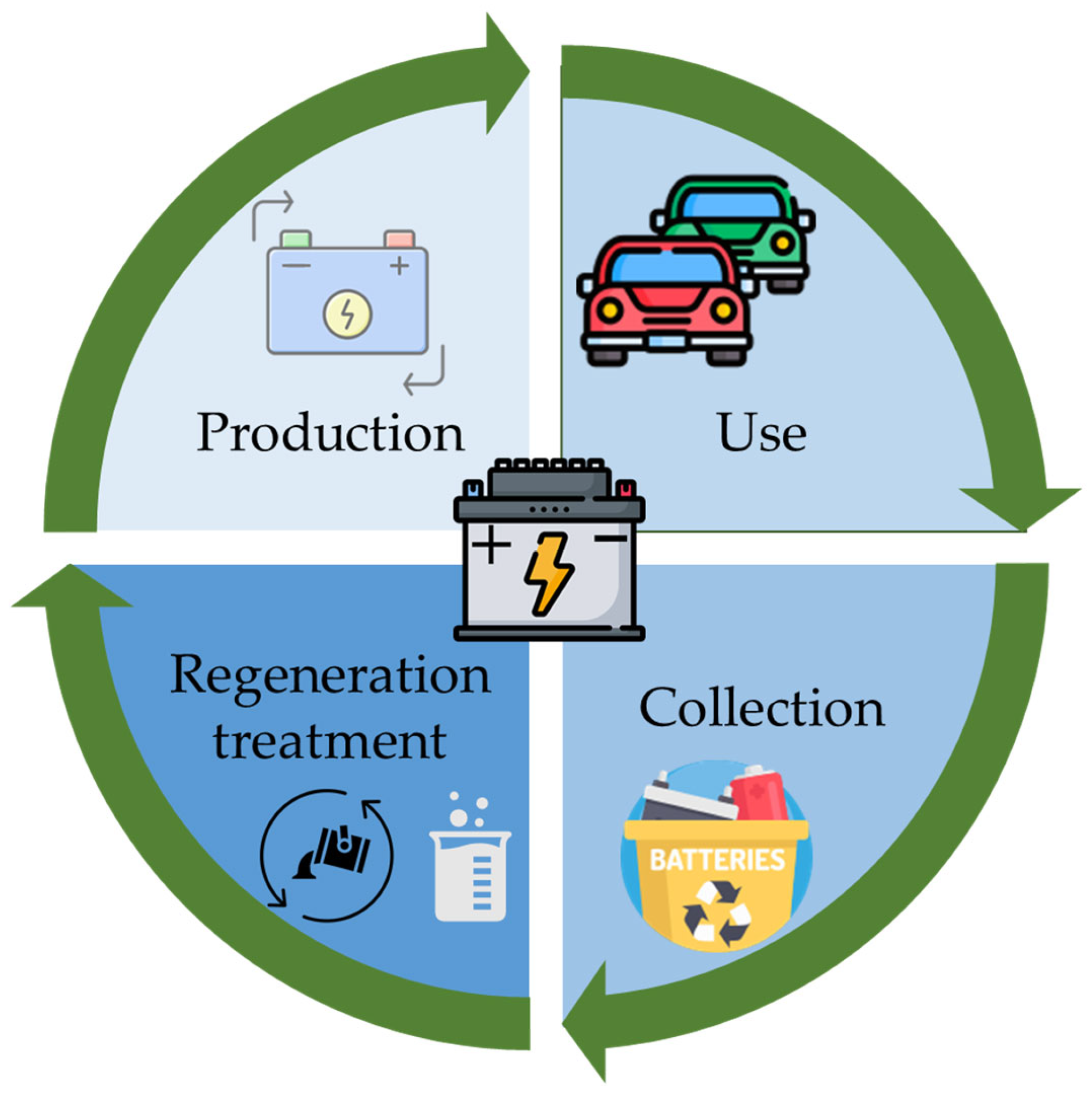

4. Sustainable Alternatives to Mitigate the Environmental Impact of LAB

Life Cycle Analysis of LAB Recycling

5. Conclusions

6. Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kebede, A.A.; Coosemans, T.; Messagie, M.; Jemal, T.; Behabtu, H.A.; Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Lithium-Ion and Lead-Acid Batteries in Stationary Energy Storage Application. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinveli, A.; Dragomir, M.; Dragomir, D. What’s Hot and What’s Not—A Simulation-Based Methodology for Fire Risk Assessment in Lead-Acid Battery Manufacturing. Processes 2025, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.V.; Vipin, B.; Ramkumar, J.; Amit, R.K. Impact of Policy Instruments on Lead-Acid Battery Recycling: A System Dynamics Approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceti, M.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Al-Sabbagh, T.A.; Shreaz, S. Impact of Lead Pollution from Vehicular Traffic on Highway-Side Grazing Areas: Challenges and Mitigation Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045064 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Wang, S.; Yang, L. Mineral Resource Extraction and Resource Sustainability: Policy Initiatives for Agriculture, Economy, Energy, and the Environment. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Gyasi, E. Sources of Lead Exposure in Various Countries. Rev. Environ. Health 2019, 34, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, K.; Ikeda, A.; Fukunaga, H.; Brune Drisse, M.N.; Onyon, L.J.; Gorman, J.; Laborde, A.; Kishi, R. How Does Formal and Informal Industry Contribute to Lead Exposure? A Narrative Review from Vietnam, Uruguay, and Malaysia. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesfeld, P.; Were, F.H.; Adogame, L.; Gharbi, S.; San, D.; Nota, M.M.; Kuepouo, G. Soil Contamination from Lead Battery Manufacturing and Recycling in Seven African Countries. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research Lead Acid Battery Market Size & Share|Industry Report 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/lead-acid-battery-market (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Sihag, N.; Vipin, B. Impact of Policies on Carbon and Lead Emissions in a Closed Loop Lead–Acid Battery Supply Chain. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2025, 16, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.M.F.; Mendes, T.F.; Wada, K. Reduction in Toxicity and Generation of Slag in Secondary Lead Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, F.; Zhou, G. Predictive Modeling for Electric Vehicle Battery State of Health: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Energies 2025, 18, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wu, Y.; Hou, P.; Liang, S.; Qu, S.; Xu, M.; Zuo, T. Environmental Impact and Economic Assessment of Secondary Lead Production: Comparison of Main Spent Lead-Acid Battery Recycling Processes in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesfeld, P. Lead Industry Influence in the 21st Century: An Old Playbook for a “Modern Metal”. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Song, Z. A Review on the State of Health Estimation Methods of Lead-Acid Batteries. J. Power Sources 2022, 517, 230710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, M.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, M.; Cai, H.; Wang, X. Environmental Risk Assessment near a Typical Spent Lead-Acid Battery Recycling Factory in China. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Du, B.; Guo, D.; Xu, H.; Fan, Y. Path to the Sustainable Development of China’s Secondary Lead Industry: An Overview of the Current Status of Waste Lead-Acid Battery Recycling. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, R.; Al Alam, M.A.; Sayeed, K.M.A.; Ahmed, S.A.; Haque, N.; Hossain, M.M.; Sujauddin, M. Patching Sustainability Loopholes within the Lead-Acid Battery Industry of Bangladesh: An Environmental and Occupational Health Risk Perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 48, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincay Pilay, D.; Llosas Albuerne, Y. Improvement of Electrical Capabilities of Automotive Lead-Acid Batteries in Comparison with the One Shot and Two Shot Methodologies”. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, S.; Baraniak, M.; Wachsmann, M.; Lota, G. Effect of Absorptive Glass Mat Soaking Method on Electrical Properties of VRLA Batteries. Energy 2024, 296, 131124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Cao, H.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Zheng, W.; Cao, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Spent Lead-Acid Battery Recycling in China—A Review and Sustainable Analyses on Mass Flow of Lead. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bača, P.; Vanýsek, P. Issues Concerning Manufacture and Recycling of Lead. Energies 2023, 16, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scur, G.; Mattos, C.; Hilsdorf, W.; Armelin, M. Lead Acid Batteries (LABs) Closed-Loop Supply Chain: The Brazilian Case. Batteries 2022, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkanen, J.P.; Johansson, L.; Kukkonen, J.; Brink, A.; Kalli, J.; Stipa, T. Extension of an Assessment Model of Ship Traffic Exhaust Emissions for Particulate Matter and Carbon Monoxide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 2641–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Hashem, M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Lead and Other Elements-Based Pollution in Soil, Crops and Water near a Lead-Acid Battery Recycling Factory in Bangladesh. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Andronic, O.; Lăcraru, A.E.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Negrei, C.; Olteanu, G. Assessing Heavy Metal Contamination in Food: Implications for Human Health and Environmental Safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schismenos, S.; Chalaris, M.; Stevens, G. Battery Hazards and Safety: A Scoping Review for Lead Acid and Silver-Zinc Batteries. Saf. Sci. 2021, 140, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanamandra, K.; Pinisetty, D.; Daoud, A.; Gupta, N. Recycling of Li-Ion and Lead Acid Batteries: A Review. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2022, 102, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, Y.; Ding, W. Design and Simulation of a Secondary Resource Recycling System: A Case Study of Lead-Acid Batteries. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, P.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, B. Analysis of a More Sustainable Method for Recycling Waste Lead Batteries: Surface Renewal Promotes Desulfurization Agent Regeneration. Waste Manag. 2022, 137, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porzio, J.; Scown, C.D. Life-Cycle Assessment Considerations for Batteries and Battery Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, Q.; Yang, J.; Han, L. A Green Recycling Process of the Spent Lead Paste from Discarded Lead–Acid Battery by a Hydrometallurgical Process. Waste Manag. Res. 2019, 37, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, H.; Dong, H.; Lin, M.; Ruan, J. A Novel Approach to Recover Lead Oxide from Spent Lead Acid Batteries by Desulfurization and Crystallization in Sodium Hydroxide Solution after Sulfation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, H.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S.; Xie, F. Preparation of NH4Cl-Modified Carbon Materials via High-Temperature Calcination and Their Application in the Negative Electrode of Lead-Carbon Batteries. Molecules 2023, 28, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loni, R.; Najafi, G.; Bellos, E.; Rajaee, F.; Said, Z.; Mazlan, M. A Review of Industrial Waste Heat Recovery System for Power Generation with Organic Rankine Cycle: Recent Challenges and Future Outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Qu, R.; Xiao, G. Environmental Impact Assessment of the Dismantled Battery: Case Study of a Power Lead–Acid Battery Factory in China. Processes 2023, 11, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozik, W.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Heidrich, O.; Christensen, P. Environmental Impacts, Pollution Sources and Pathways of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 6099–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, K.I.A.; Nurunnahar, S.; Kabir, M.L.; Islam, M.T.; Baker, M.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.; Hasan, M.A.; Sikder, A.; Kwong, L.H.; et al. Child Lead Exposure near Abandoned Lead Acid Battery Recycling Sites in a Residential Community in Bangladesh: Risk Factors and the Impact of Soil Remediation on Blood Lead Levels. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’shea, M.J.; Toupal, J.; Caballero-Gómez, H.; McKeon, T.P.; Howarth, M.V.; Pepino, R.; Gieré, R. Lead Pollution, Demographics, and Environmental Health Risks: The Case of Philadelphia, USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briseño-Bugarín, J.; Araujo-Padilla, X.; Escot-Espinoza, V.M.; Cardoso-Ortiz, J.; Flores de la Torre, J.A.; López-Luna, A. Lead (Pb) Pollution in Soil: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Contamination Grade and Health Risk in Mexico. Environments 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, D.; Ogundiran, M.B.; Babayemi, J.O.; Jha, M.K. Material and Substance Flow Analysis of Used Lead Acid Batteries in Nigeria: Implications for Recovery and Environmental Quality. J. Health Pollut. 2020, 10, 200913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Li, C.; Zhu, F.; Luo, X.; Feng, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, C.; Hartley, W.; Xue, S. Effect of Potentially Toxic Elements on Soil Multifunctionality at a Lead Smelting Site. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Sultana, J.; Hasan, S.S.; Nurunnahar, S.; Baker, M.; Raqib, R.; Rahman, S.M.; Kippler, M.; Parvez, S.M. Effectiveness of Soil Remediation Intervention in Abandoned Used Lead Acid Battery (ULAB) Recycling Sites to Reduce Lead Exposure among the Children. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DTSC Lead-Acid Battery Recycling Facility Investigation and Cleanup Program | Department of Toxic Substances Control. Available online: https://dtsc.ca.gov/labric_annual-report-to-the-legislature/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Su, D.; Mei, Y.; Liu, T.; Amine, K. Global Regulations for Sustainable Battery Recycling: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Das, A.P. Lead Pollution: Impact on Environment and Human Health and Approach for a Sustainable Solution. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2023, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaba, A.H.; Lawal, I.M.; Birniwa, A.H.; Affam, A.C.; Usman, A.K.; Soja, U.B.; Saleh, D.; Hussaini, A.; Noor, A.; Aliyu Yaro, N.S. Sources of Water Contamination by Heavy Metals. In Membrane Technologies for Heavy Metal Removal from Water; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, M.; Cai, H.; Wang, X. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination in Air, Water, Soil, and Crops Adjacent to a Spent Lead-Acid Battery Storage Facility. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, P.; Liu, D.; Hua, D.; Song, J. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Contamination and Associated Human Health Risk in Soils around a Battery Industrial Zone in Henan Province, Central China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkiewicz, A.E.; Backstrand, J.R. Lead Toxicity and Pollution in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvizuri-Tintaya, P.A.; Villena-Martínez, E.M.; Avendaño-Acosta, N.; Lo-Iacono-Ferreira, V.G.; Torregrosa-López, J.I.; Lora-García, J. Contamination of Water Supply Sources by Heavy Metals: The Price of Development in Bolivia, a Latin American Reality. Water 2022, 14, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Q.; Yu, J.; Xia, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Li, J. Pollution-Free Recycling of Lead and Sulfur from Spent Lead-Acid Batteries via a Facile Vacuum Roasting Route. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabolude, G.; Knoble, C.; Vu, A.; Yu, D. Comprehensive Lead Exposure Vulnerability for New Jersey: Insights from a Multi-Criteria Risk Assessment and Community Impact Analysis Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brouwere, K.; Verdonck, F.; Geerts, L.; Navis, S.; Vanhamel, M. Assessment of Human Exposure to Environmental Sources of Lead Arising from the Lead Battery Manufacturing and Recycling Sector in Europe: Demonstration of a Tiered Approach in a Case Study. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2021, 32, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Sekyere, K.; Aladago, D.A.; Leverenz, D.; Oteng-Ababio, M.; Kranert, M. Environmental Impacts on Soil and Groundwater of Informal E-Waste Recycling Processes in Ghana. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sederholm, J.G.; Lan, K.W.; Cho, E.J.; Dipto, M.J.; Gurumukhi, Y.; Rabbi, K.F.; Hatzell, M.C.; Perry, N.H.; Miljkovic, N.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrometallurgical Recycling for Cathode Active Materials. J. Power Sources 2023, 580, 233345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelio, A.; Zanoletti, A.; Bontempi, E. Recent Progress in Pyrometallurgy for the Recovery of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review of State-of-the-Art Developments. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 46, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobianowska-Turek, A.; Fornalczyk, A.; Zygmunt, M.; Janosz, M. Recovery of Technical Li2CO3 from Dust Obtained after Pyrometallurgical Processing of Li-Ion Battery Masses on a Quarter-Technological Scale. Waste Manag. 2025, 204, 114943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toro, L.; Moscardini, E.; Baldassari, L.; Forte, F.; Falcone, I.; Coletta, J.; Toro, L. A Systematic Review of Battery Recycling Technologies: Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Energies 2023, 16, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perocillo, Y.K.; Pirard, E.; Léonard, A. Process Simulation-Based LCA: Li-Ion Battery Recycling Case Study. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Demopoulos, G.P. Hydrometallurgical Recycling Technologies for NMC Li-Ion Battery Cathodes: Current Industrial Practice and New R&D Trends. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1932–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dubarry, M.; Ziebert, C.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, B. A Review on Dynamic Recycling of Electric Vehicle Battery: Disassembly and Echelon Utilization. Batteries 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, K. A Comprehensive Review on Human–Robot Collaboration Remanufacturing towards Uncertain and Dynamic Disassembly. Manuf. Rev. 2024, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liao, H. Literature Review on Power Battery Echelon Reuse and Recycling from a Circular Economy Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herva, M.; García-Diéguez, C.; Franco-Uría, A.; Roca, E. New Insights on Ecological Footprinting as Environmental Indicator for Production Processes. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 16, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glogic, E.; Sonnemann, G.; Young, S.B. Environmental Trade-Offs of Downcycling in Circular Economy: Combining Life Cycle Assessment and Material Circularity Indicator to Inform Circularity Strategies for Alkaline Batteries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán-Saldivar, J.; Gaugler, T.; Helbig, C.; Rathgeber, A.; Sonnemann, G.; Thorenz, A.; Tuma, A. Design of an Endpoint Indicator for Mineral Resource Supply Risks in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: The Case of Li-Ion Batteries. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Tosti, L.; Basosi, R.; Cusenza, M.A.; Parisi, M.L.; Sinicropi, A. Environmental Optimization Model for the European Batteries Industry Based on Prospective Life Cycle Assessment and Material Flow Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cong, N.; Zhang, X.; Yue, Q.; Zhang, M. Life Cycle Assessment and Carbon Reduction Potential Prediction of Electric Vehicles Batteries. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klöpffer, W.; Grahl, B. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide to Best Practice; Wiley-VCH, Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; ISBN 3527329862. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Fan, E.; Xue, Q.; Bian, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, R. Toward Sustainable and Systematic Recycling of Spent Rechargeable Batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7239–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Song, Y.; Mao, J. Quantitative Analysis of the Material, Energy and Value Flows of a Lead-Acid Battery System and Its External Performance. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Challenges in Evaluating Emerging Battery Technologies: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhistira, R.; Khatiwada, D.; Sanchez, F. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion and Lead-Acid Batteries for Grid Energy Storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, X.; Zhang, D. Analysis on the Optimal Recycling Path of Chinese Lead-Acid Battery under the Extended Producer Responsibility System. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Pan, D. Impact of Waste Slag Reuse on the Sustainability of the Secondary Lead Industry Evaluated from an Emergy Perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas Marreros, S.; Alcántara, A.C.; Alcántara, M.C.; Madera, P.P.; Sánchez, J.; Velarde, L.; Palacios, A.Y.; Cruz, A.H. Management Situation of Lead Acid Batteries in Perú. Ing. Ambient. 2022, 25, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cai, J.; Guo, J.; Mai, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. The Lead Burden of Occupational Lead-Exposed Workers in Guangzhou, China: 2006–2019. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.K.; Nayeem, A.A.; Islam, M.; Akter, M.M.; Carter, W.S. Critical Review of Lead Pollution in Bangladesh. J. Health Pollut. 2021, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battery Council International New Study Confirms Lead Batteries Maintain 99% Recycling Rate|Battery Council International. Available online: https://batterycouncil.org/news/press-release/new-study-confirms-lead-batteries-maintain-remarkable-99-recycling-rate/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Pure Earth Bangladesh: Toxic Lead Cleanup Brings Hope to Residents in Mirzapur and Beyond—Pure Earth. Available online: https://www.pureearth.org/bangladesh-toxic-lead-cleanup-brings-hope-to-residents-in-mirzapur-and-beyond/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Mandade, P.; Weil, M.; Baumann, M.; Wei, Z. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Solid-State Batteries: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 13, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Matrix | Ubication | Concentrations | Polluting Sources | Ecological and Health Effects (Type of Exposure) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | China | 30.4–41.3 mg/kg | Slag deposit in LAB industrial park | Moderate cumulative contamination, potential bioaccumulation in crops and water (community exhibition) | [50] |

| Bangladesh | 966 mg/kg | Artisanal battery recycling, plastic burning, electrolyte dumping. | Extreme pollution, mass poisoning (community exhibition) | [26] | |

| Bolivia | 2400 mg/kg | Disposal of slag and metallurgical waste | Persistent urban pollution, affecting family gardens (community exhibition) | [52] | |

| Mexico | >5000 mg/kg | Semi-industrial recycling workshops and uncontrolled smelters | Degraded agricultural soils, chronic exposure of children, Pb in vegetables (15–30 mg/kg) (community exhibition) | [41] | |

| Air | USA | 0.3–2 × 10−6 mg/L | Smelting and improper disposal in residential areas | 73% of children >5 µg/dL Pb in blood (occupational exposure) | [45] |

| China | 2.4 × 10−6 mg/L | Formal recycling of LAB, smelting, and oxidation of Pb | Non-carcinogenic risk, higher exposure in children (3.46 × 10−2 mg/kg day) (occupational exposure) | [53] | |

| Czech Republic | 50 × 10−6 mg/L | Casting, oxidation, plate curing, and handling of PbO | Respiratory and neurological risk, high occupational exposure (occupational exposure) | [23] | |

| Water | China | 0.5–2 mg/L | Dissolution of PbO2 and PbSO4 in industrial effluents | Bioaccumulation in fish and invertebrates, enzymatic alteration, and oxidative stress (community exhibition) | [34] |

| Nigeria | 1.6–5.4 mg/L | Electrolyte and slag leachate spills | High bioavailability (45–50%), degradation of agricultural soils, anemia in children (community exhibition) | [42] | |

| Bangladesh | 3.8 mg/L | Acid leaks and leaching into aquifers | High presence in children’s health biomarkers (community exhibition) | [44] | |

| Bangladesh | 11 mg/L | Artisanal battery recycling, plastic burning, electrolyte dumping | Local acid rain, mass poisoning (community exhibition) | [26] |

| Technology | Lead Recovery Rate (%) | Carbon Footprint (t CO2-eq/t Pb) | SO2 and PbO Emissions (kg/t Pb) | Energy Demand (GJ/t Pb) | Estimated Cost (USD/t Pb) | Environmental Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional pyrometallurgy | 90–98 | 1.8–2.7 | 22–35 | 6.5–8.2 | 600–900 | Mature technology; high metallurgical efficiency | [29] |

| Advanced pyrometallurgy (with emission control) | 95–99 | 1.2–1.6 | 8–12 | 5.5–6.5 | 850–1100 | 40–50% reduction in emissions with filters and heat recovery | [58,59] |

| Hydrometallurgy (acid leaching and electrowinning) | 96–99 | 0.4–0.8 (≤0.3 with renewable electricity) | <5 | 3.0–4.2 | 1000–1300 | 70–80% lower CO2 and SO2 emissions; Pb purity > 99.9% | [57] |

| Informal (artisanal recycling) | 60–85 | 4.0–6.5 | >50 | Variable | 200–400 | Low upfront cost; locally accessible | [60] |

| Localization | Findings | Goal | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam, Uruguay, and Malaysia | High lead exposure in formal and informal industries; lack of strategic efforts to understand sources of exposure | To analyze how formal and informal industries contribute to lead exposure in Vietnam, Uruguay, and Malaysia | [8] |

| Nigeria | The flow of materials and substances from used LAB and their implications for environmental quality in Nigeria revealed that battery pastes are heterogeneous, with only lead exceeding the 1000 mg/kg total threshold limit concentration | To study the environmental implications of the flow of materials and substances from the used LAB | [42] |

| Peru | There are no engineering controls or adequate regulations for LAB management | To design and implement a robust legal framework that clearly defines the responsibilities of each stakeholder involved in LAB management and provides for effective sanctions on those who fail to comply with the established quality and safety standards | [78] |

| Brazil | Identification of the mechanisms that drive recycling programs and proposal of an explanatory framework | To examine how regulations and sustainability strategies implemented by LAB manufacturers are coordinated with various stakeholders involved, promoting economic development, social well-being, and environmental protection | [24] |

| China | High technological efficiency in LAB recycling, with high occupational risks due to lead exposure | To strengthen and update workplace safety policies to ensure safe and healthy work environments | [22,79] |

| Bangladesh | Environmental pollution due to improper management of lead-containing elements. | To institute controls in the LAB recycling process to prevent environmental pollution | [80] |

| Europe | More than 99% of LAB are recycled for reuse in manufacturing new batteries. | To promote the circular economy through complete and efficient recycling. | [16] |

| Africa | Lack of regulation in recycling and emissions management; significant environmental risks. | To identify regulatory gaps and instigate improvements in recycling regulations. | [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pincay-Pilay, D.A.; Carrasco, E.F. Environmental Impact of Lead-Acid Batteries: A Review of Sustainable Alternatives for Production and Recycling Based on Life Cycle Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310815

Pincay-Pilay DA, Carrasco EF. Environmental Impact of Lead-Acid Batteries: A Review of Sustainable Alternatives for Production and Recycling Based on Life Cycle Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310815

Chicago/Turabian StylePincay-Pilay, Dimas Alberto, and Eugenio F. Carrasco. 2025. "Environmental Impact of Lead-Acid Batteries: A Review of Sustainable Alternatives for Production and Recycling Based on Life Cycle Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310815

APA StylePincay-Pilay, D. A., & Carrasco, E. F. (2025). Environmental Impact of Lead-Acid Batteries: A Review of Sustainable Alternatives for Production and Recycling Based on Life Cycle Analysis. Sustainability, 17(23), 10815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310815