1. Introduction

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) has consolidated globally as the principal paradigm for ocean governance, seeking to harmonize burgeoning demands for resources with conservation imperatives [

1]. This planning is fundamental to achieving broad sustainability objectives, including renewable energy targets, energy security, and climate change mitigation, which are central pillars of the sustainable blue economy [

2]. However, the conceptual architecture of most MSP processes operates under an implicit premise that Earth system science has shown to be untenable: that of climatic stationarity [

3]. While existing research has extensively modeled physical climate impacts (e.g., sea-level rise), there remains a critical gap in quantifying how deep climatic uncertainty translates into operational risks for maritime industries. This lack of integration between stochastic climate projections and operational downtime analysis creates a systemic vulnerability in long-term planning, precisely when predictability is most needed.

The necessity of transcending this static model and evolving towards “Climate-Smart MSP” is, therefore, one of the most urgent challenges for ocean governance in the Anthropocene [

4], demanding a deeper integration between climate science and public policymaking [

5]. This integration should not be merely technical, but also procedural, ensuring that climate adaptation strategies are embedded within participatory, data-informed governance structures [

6,

7].

This paradigm mismatch yields profound economic consequences. The allocation of capital to long-lifecycle marine infrastructure—such as offshore wind energy farms—becomes a high-risk exercise when feasibility analysis disregards the future trajectory of operational conditions. The failure to quantify how the intensification of extreme events will impact downtime and maintenance costs can lead to maladaptive investments and, ultimately, stranded assets [

8], thereby compromising the resilience of a nation’s entire Blue Economy. Beyond financial risk, this vulnerability threatens crucial socioeconomic outcomes, such as the stability of clean energy supplies, local job creation, and the potential for a just energy transition for coastal communities [

9,

10]. For Brazil, which is poised for unprecedented maritime expansion, this analytical gap constitutes an imminent obstacle to its sustainable and equitable development.

Unlike traditional MSP approaches that often address climate uncertainty through qualitative vulnerability assessments or focus solely on slow-onset physical hazards (e.g., sea-level rise), this study differentiates itself by quantifying the specific operational consequences of high-frequency climate variability (waves and wind). The primary advantage of this approach lies in transforming abstract climatic uncertainty into a tangible financial metric (operational downtime). This allows for the direct pricing of resilience in capital planning, moving beyond static risk mapping to dynamic investment analysis.

To address this gap, this paper introduces, validates, and discusses FARO (Framework for Adaptive Operational Risk Analysis), a methodological and computational framework designed to facilitate the transition to a dynamic and risk-based MSP. FARO directly responds to calls for tools that translate cutting-edge science into actionable insights for decision-making under conditions of deep uncertainty [

11,

12].

The objective of this work is threefold: (1) to present the architecture of FARO, which integrates regional model projections (INPE/CMIP5), statistical downscaling via machine learning (XGBoost), and technological sensitivity analysis; (2) to empirically validate its robustness through a prospective case study in the emerging Brazilian offshore wind industry; and (3) to demonstrate how the framework’s outputs can substantiate the formulation of more resilient investment strategies and policies. Although this study focuses on the Brazilian context—a globally relevant case due to its vast maritime territory and urgent need for energy transition—, the FARO is designed as a scalable and broadly applicable methodological structure. It is reproducible for other coastal nations and different sectors of the blue economy (e.g., aquaculture, port logistics) facing similar climatic uncertainties, particularly those in the Global South, where data scarcity and high vulnerability converge [

13].

In essence, this article proposes and validates a methodology to translate climatic uncertainty into quantifiable financial risk, thereby enabling the pricing of technological adaptation costs in the planning of maritime assets. The central innovation of this article, therefore, is to provide a decision-support structure that is not merely academic, but operational, connecting high-resolution climatological projections to the specific financial and operational decisions managers must make, thereby fostering development that is simultaneously sustainable and resilient.

2. Literature Review

The transition toward a dynamic, climate-aware Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) capable of transcending the stationarity paradigm is not an incremental task; rather, it is one that demands a transdisciplinary synthesis of knowledge for effective and equitable governance. The theoretical foundation of the FARO is constructed upon the articulation of advances in three distinct yet interdependent research domains: (1) the conceptual evolution of MSP toward adaptive governance under deep uncertainty; (2) the techno-economic risk analysis for maritime assets in a non-stationary environment; and (3) the new frontiers of predictive modeling for the Earth system via Machine Learning. This review critically analyzes the state-of-the-art in each of these domains to establish the fundamental methodological gap that FARO is designed to address.

MSP has emerged as the principal governance paradigm for the oceans [

1]. However, its long-term efficacy is challenged by the premise of climatic stationarity [

3]. This premise has become untenable [

14], and planning that ignores it may lead to a “lock-in” of investments in maladaptive infrastructures [

15]. In response, the “Climate-Smart MSP” concept has gained prominence [

4]. Nevertheless, the operationalization of this concept remains a challenge, with many qualitative approaches failing to provide decision-makers with quantitative tools to assess socioeconomic risks [

11]. More critically, this gap impedes evidence-based governance, where the trade-offs between economic development, environmental conservation, and social equity can be transparently debated with stakeholders [

7,

16]. The vanguard of research now argues that the next evolution of MSP depends on the development of “Decision-Support Frameworks” [

12] that can translate climatic uncertainty into actionable risk metrics, enabling a transition toward adaptive risk management [

17], which is essential for the formulation of robust public policies. Indeed, the challenge for MSP now lies in creating and validating quantitative tools that integrate dynamic projections, thereby bridging the barrier between science and the practice of governance for sustainability [

18].

This imperative for quantitative tools directly impacts the economic viability of marine infrastructure. In the offshore wind sector, Operation and Maintenance (O&M) costs are a critical factor of the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), with climate-induced downtime being the most sensitive factor [

19,

20]. Techno-economic models confirm that variations in “good weather windows” can drastically alter a project’s profitability [

21], jeopardizing not only the return on investment but also the broader socioeconomic benefits, such as energy security and job creation [

9]. The primary mitigation strategy for this risk is technological (a CAPEX/OPEX trade-off). However, the literature exploring this trade-off almost invariably does so using historical time series, failing to answer the strategic question: what is the value of an investment in technological resilience in a worsening climate scenario? [

22]. This failure to integrate projections into risk models exposes investors to underestimated risks [

8]. Financial models that do not incorporate climatic non-stationarity fail to price optionality and flexibility [

23], underestimating the value of resilience and acting as a barrier to financing the sustainable energy transition [

24].

To address this, the downscaling of projections from global climate models (GCMs) to locally relevant scales is essential. Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as the enabling technology for robust statistical downscaling [

25]. Algorithms such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) have demonstrated a superior capacity to capture the complex, non-linear relationships between large-scale atmospheric forcings and local meteoceanographic responses [

26,

27]. The rise in these methods represents a paradigm shift [

28], allowing for the agile generation of multiple scenarios, which is vital for adaptive decision support. In the specific domain of ocean geosciences, the application of ML to project future wave and wind climates is advancing rapidly [

29,

30], and the efficacy of ML methods for bias correction has been confirmed [

31]. The scientific maturity of these methods now permits their integration into risk analysis frameworks.

The analysis of the literature reveals three conclusions: (1) MSP must transcend stationarity and evolve into a quantitative, adaptive governance paradigm; (2) The viability of Blue Economy assets is a function of operational risk, which must incorporate climate projections; (3) Machine Learning provides the validated predictive capability to generate these local projections. However, the literature also exposes a profound fragmentation of knowledge. The absence of a methodological framework that promotes the systematic synthesis of these domains is the primary barrier to operationalizing a truly adaptive MSP [

5]. It is precisely this integration gap that the FARO is designed to fill.

3. Methodology and Analysis

The quantitative analysis in this study is the product of a two-stage methodological process: (1) a modeling and statistical downscaling phase to generate high-resolution wave projections, and (2) the application of a risk analysis pipeline, the FARO (Framework for Adaptive Operational Risk Analysis) v1.0, to convert these projections into operational metrics. The entire workflow was implemented in Python (v.3.10), utilizing open-source libraries (Scikit-learn, XGBoost, Xarray, Pandas, Cartopy). The generative AI model Gemini 1.5 Pro (Google) was utilized to assist in the preparation of the manuscript; all AI-assisted content was critically reviewed, edited, and validated by the authors, who assume full responsibility for the publication.

3.1. Description of the Studied Area

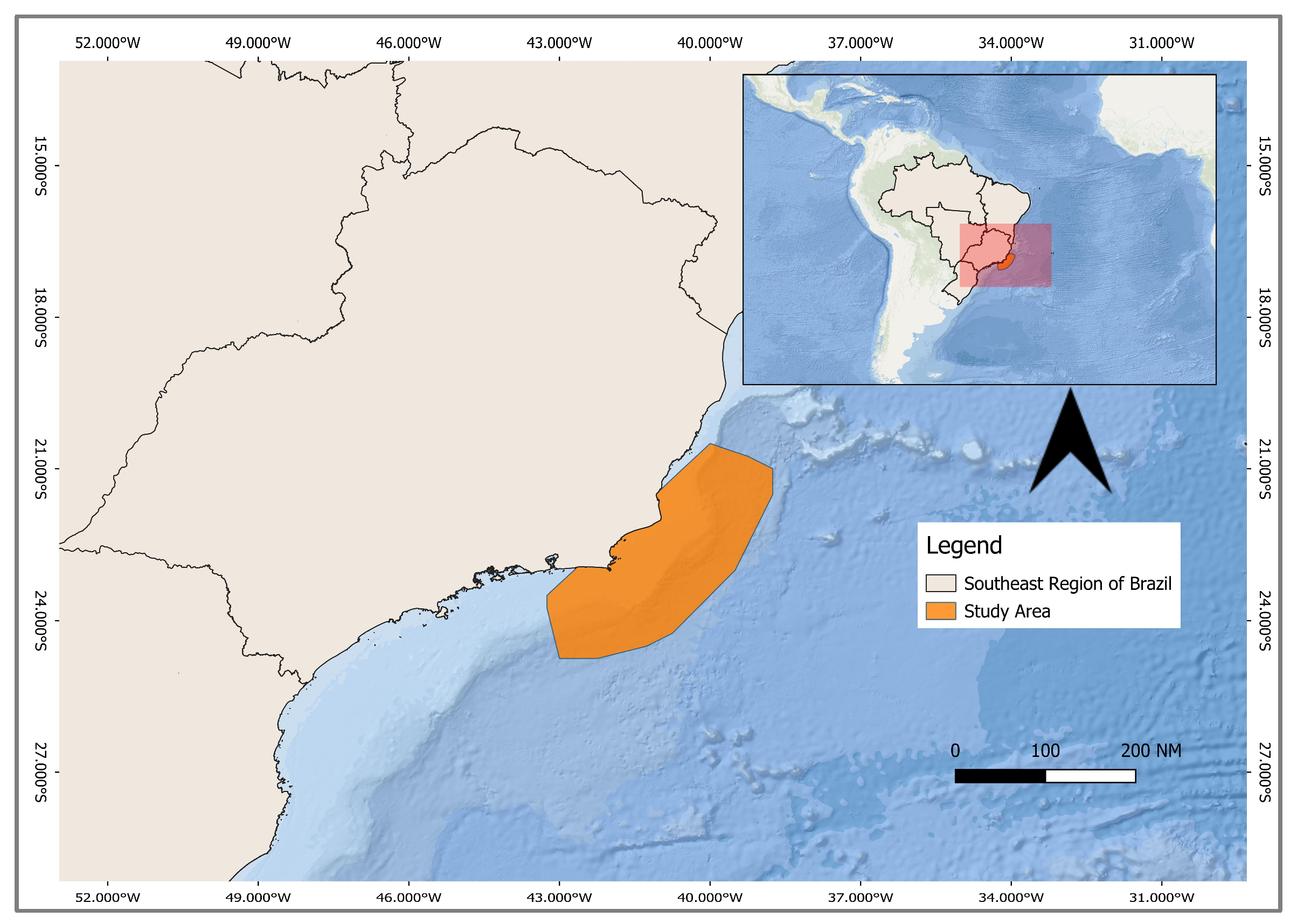

The study area is located in the Southeastern Marine Region of Brazil (

Figure 1), a region of strategic importance for the country’s energy transition due to logistical synergies with the O&G industry (Campos Basin) and the high wind potential identified by EPE [

32]. The analysis domain (441 grid points) focuses precisely on these high-potential areas, ensuring direct relevance for decision-making.

This region represents the economic nucleus of Brazil, characterized by high population density and intense industrial activity. To contextualize the anthropogenic drivers of energy demand and the spatial competition facing offshore wind development,

Table 1 presents a synthesis of the key socio-economic indicators and conflicting marine uses for the adjacent coastal states (Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, and São Paulo).

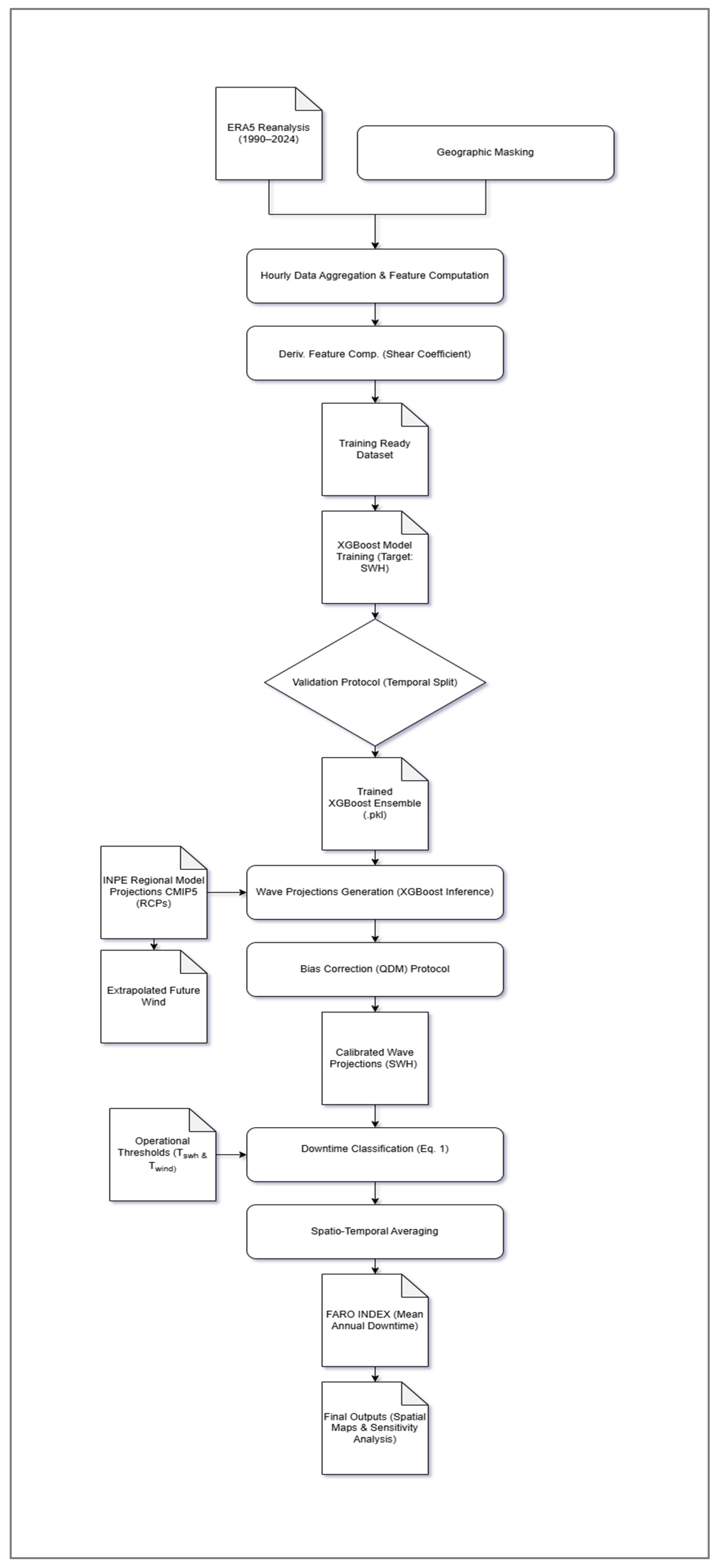

To address the challenge of quantifying climate operational risk within this complex domain, a structured computational workflow was developed.

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological framework (FARO), detailing the data integration pipeline from raw climate inputs to the final risk decision indicators.

3.2. Stage 1: Statistical Downscaling and Generation of Wave Projections

3.2.1. Acquisition and Pre-Processing of Historical Data

The historical dataset (1990–2024) was extracted from the ERA5 reanalysis (ECMWF), considered the state-of-the-art (0.25° spatial resolution, hourly temporal). Two classes of variables were used:

Predictor Variables (Atmospheric): The zonal and meridional wind components ((u,v) at 10 m and 100 m).

Target Variables (Oceanographic): Significant Wave Height (SWH), Mean Wave Period (MWP), and Mean Wave Direction (MWD).

The hourly data were aggregated into daily statistics (mean, maximum, minimum, standard deviation), and derived features (wind speed magnitude, shear coefficient) were computed.

3.2.2. Training and Validation of the Predictive Model

To establish the functional relationship between large-scale atmospheric forcings and the local sea state, a statistical downscaling approach was employed. An ensemble of Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) models was independently trained for each grid cell. The choice of XGBoost over Deep Learning architectures (e.g., LSTM) was driven by its proven superior performance on tabular structured data and computational efficiency [

27]. Hyperparameters were tuned using 5-fold cross-validation (1000 estimators, learning rate 0.01) to prevent overfitting. A rigorous validation protocol was implemented with a strict temporal split (training: 1990–2015; validation: 2016–2024) to prevent temporal leakage. The final performance achieved a Coefficient of Determination (

R2) of 0.8885 and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.1446 m. Spatially, performance remained robust across the domain, with a slight expected reduction in immediate coastal cells (

R2 ≈ 0.82) due to shallow-water effects. Regarding extremes, the model demonstrated high skill in capturing upper quantiles, minimizing the saturation bias often observed in linear downscaling methods.

3.2.3. Generation and Bias Correction of Future Projections

This is the central methodological step that differentiates this study. The choice of the projection data source is fundamental to the validity of the local-scale risk analysis. Global climate models (GCMs), such as those from the CMIP6 ensemble, possess coarse spatial resolutions (typically >100 km) [

36,

37]. This scale is inadequate for capturing the local meteoceanographic phenomena that dictate the daily operational risk for marine infrastructures. Therefore, the choice of a high-resolution regional model is not a limitation, but a methodological requirement.

The atmospheric forcings projections (2025–2100) were obtained from the INPE regional model simulations (Eta-Model nested in CMIP5, RCP 4.5 and 8.5). The selection of this dataset, prioritizing the Eta-Model (20 km resolution) over newer global CMIP6 ensembles (typically >100 km), was a deliberate methodological choice. For wave downtime quantification, mesoscale spatial resolution is critical to capture local extreme events. It is crucial to emphasize that performing a proprietary dynamic downscaling of the new CMIP6 global ensemble (or relying on emerging CORDEX products) was considered but discarded due to the prohibitively high computational cost and the current lack of robust validation for the South Atlantic domain. Therefore, utilizing the official INPE-Eta dataset [

38,

39] represents the scientifically most rigorous approach. It remains the only high-resolution, public, and auditable projection dataset available for the Brazilian territory, serving as the validated benchmark for regulatory planning by the Brazilian Energy Research Office (EPE) [

32].

The FARO, then, executes a second ‘downscaling’ layer (in cascade): the trained XGBoost ensemble (3.2.2) utilizes these high-resolution regional atmospheric forcings from INPE to generate the daily wave projections (swh_mean_pred). This hybrid approach (dynamic-statistical downscaling) represents a methodological innovation, enabling a robust and replicable proof-of-concept aligned with the best available data sources for the Brazilian context.

Finally, to correct for residual distributional biases, a non-parametric bias correction protocol (Quantile Delta Mapping) was applied to the generated wave time series [

40]. This method was calibrated using the historical overlap period (1990–2015). A key advantage of QDM is that it explicitly preserves the model’s projected relative trends (deltas) for all quantiles, including extremes, ensuring that the future signal of wave height intensification is physically consistent with the climate drivers.

3.3. Stage 2: Risk Analysis Pipeline (FARO v1.0)

To ensure the reproducibility of the computational pipeline and clarify the specific variables utilized for feature engineering and bias correction,

Table 2 details the complete dataset specifications. This summary explicitly distinguishes between the raw atmospheric inputs (from ERA5 and INPE) and the derived oceanographic features computed to train the XGBoost ensemble.

3.3.1. Data Processing and Harmonization

The FARO analysis engine processes the generated wave projections. The pipeline loads the daily wave and wind projections (extrapolated to 100 m via the Wind Power Law). The data is spatially filtered using a geographic mask based on the high-potential areas identified by the Brazilian Energy Research Office (EPE) “Offshore Wind Roadmap” [

32]. This alignment with official energy policy documents is crucial, as it connects the technical-scientific risk analysis directly to the decision-making process and stakeholder engagement within the scope of MSP governance [

7,

16]. The procedure resulted in 441 grid points focused on the priority areas.

The spatial domain was defined using a ‘Centroid Inclusion’ method: ERA5 grid cells were selected for analysis if their centroids fell within the high-potential polygons defined by the EPE Roadmap. We acknowledge that the 0.25-degree resolution (~27 km) of the reanalysis imposes a limitation for nearshore micro-siting; however, this resolution is methodologically appropriate for the meso-scale regional risk assessment proposed by FARO.

3.3.2. Quantification of the Operational Window

The core of the analysis is the daily classification of operational viability. A day (

d) in a cell (

c) is classified as non-operational (downtime,

D = 1) if conditions exceed the safety thresholds (Equation (1)).

where

is the significant wave height and

is the wind speed at 100 m. The

is the wave height threshold and

is the wind speed threshold for service operation vessels (SOVs) [

19,

20]. This binary classification serves as a standard industry proxy for ‘Waiting on Weather’ (WoW) downtime. While offshore operations involve dynamic decision-making, strategic long-term planning relies on these probabilistic exceedance thresholds (e.g., DNV-ST-N001 [

41]) to estimate fleet availability and budget for weather-related financial losses. The standard analysis uses

= 2.0 m and

= 15.0 m/s.

3.4. Generation of Risk Analysis Products

The framework generates three central outputs:

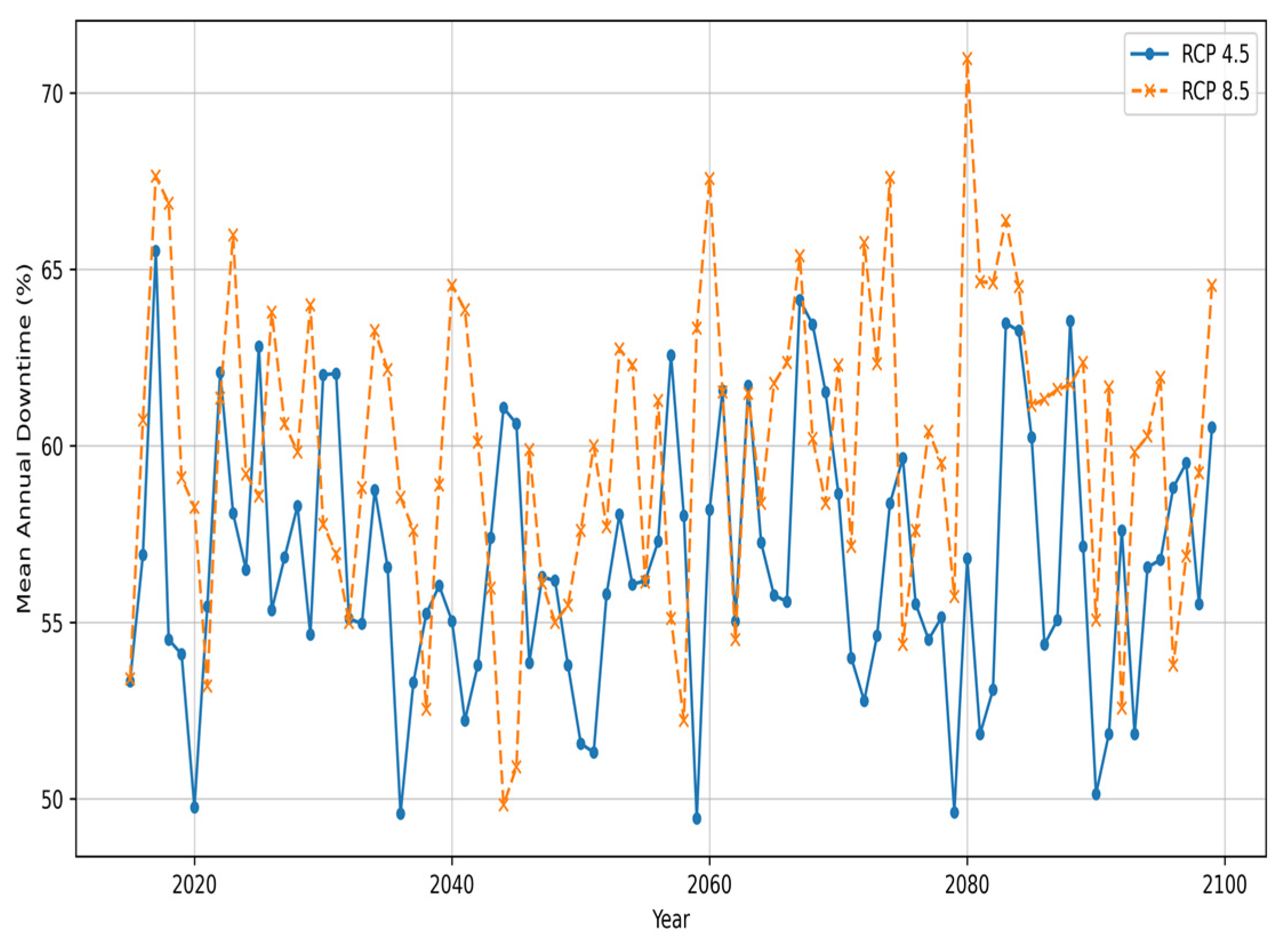

Temporal Risk Analysis (

Figure 3): The mean annual downtime (

), calculated by spatial and temporal averaging, illustrating the evolution of risk (RCP 4.5 vs. 8.5).

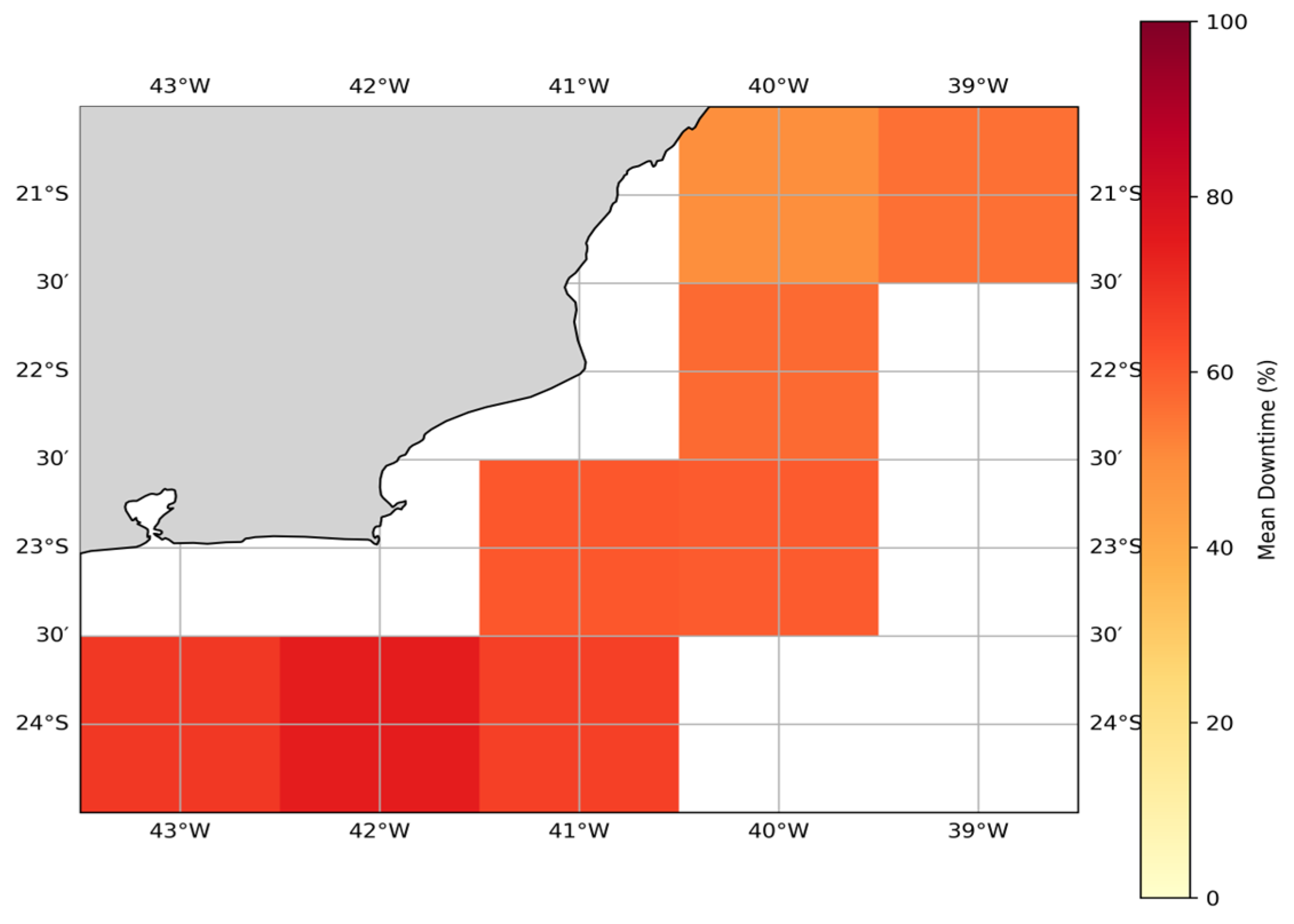

Spatial Risk Analysis (

Figure 4): The mean downtime for the end-of-century (2080–2099, RCP 8.5) for each grid cell, generating a georeferenced risk map.

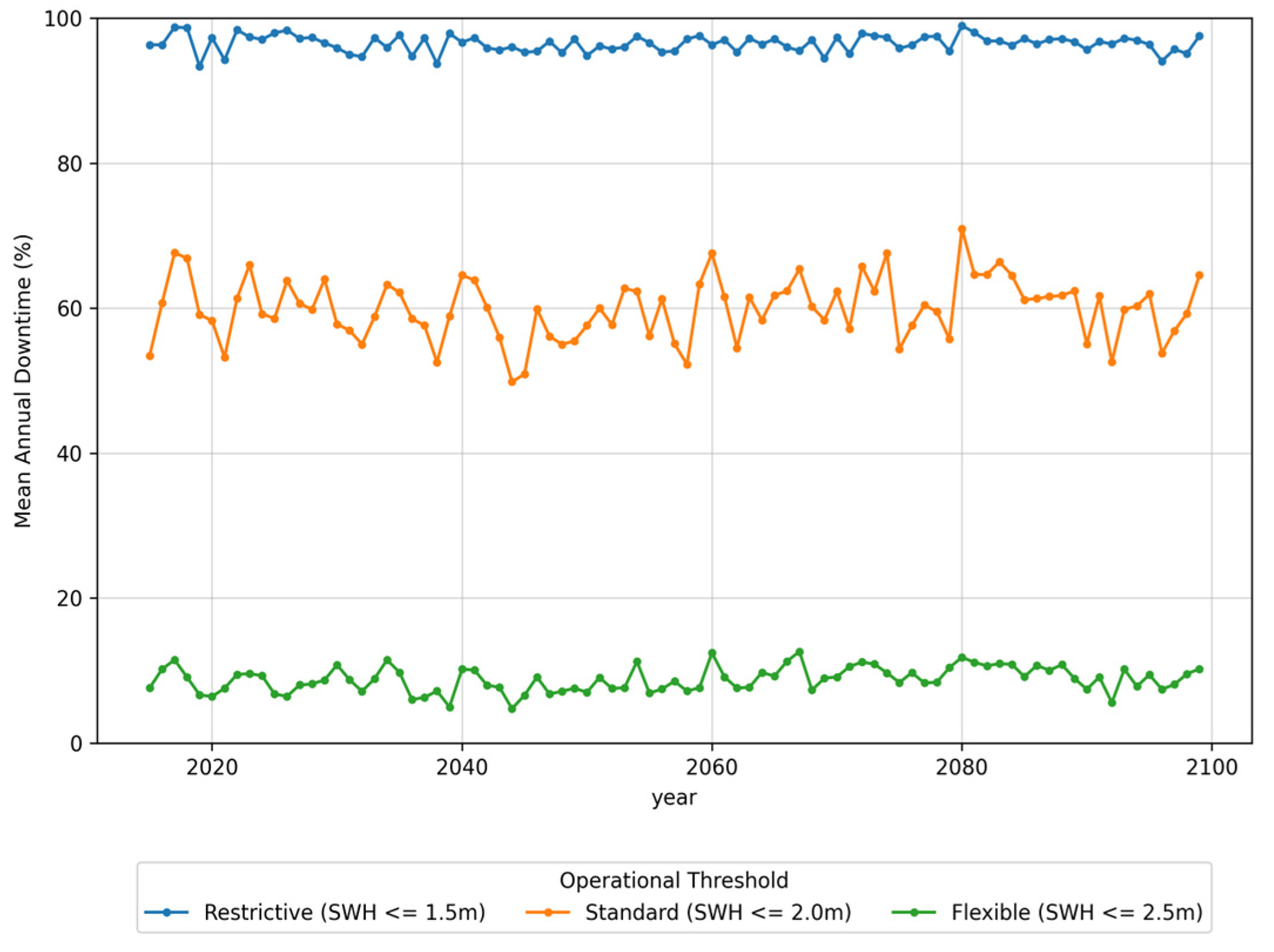

Technological Sensitivity Analysis (

Figure 5): The temporal risk analysis (RCP 8.5) is executed iteratively, varying the

for three technological classes: Restrictive (1.5 m), Standard (2.0 m), and Flexible (2.5 m).

Figure 3.

Projected Operational Downtime Evolution (SWH 2.0 m), comparing RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios. Note the higher variability and worsening trend under the high-emissions scenario (RCP 8.5).

Figure 3.

Projected Operational Downtime Evolution (SWH 2.0 m), comparing RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios. Note the higher variability and worsening trend under the high-emissions scenario (RCP 8.5).

3.5. Availability and Reproducibility

In alignment with the principles of open science and demonstrating the study’s replicability even without specific funding, the FARO pipeline source code is available on GitHub (

https://github.com/Rinalde-Paulo/FARO-Framework, accessed on 5 November 2025) under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. To ensure full reproducibility, the repository includes a comprehensive requirements.txt file (listing all dependencies such as XGBoost, Xarray, and CDSAPI), a conda environment configuration, and estimated runtime benchmarks for standard workstations. Additionally, a detailed README guide provides step-by-step instructions for acquiring the raw datasets (ERA5 and INPE) and replicating the pre-processing workflow.

4. Results

This section presents the outcomes derived from the application of the FARO, followed by a detailed case study analysis, facilitated through the three central deliverables generated by the methodology.

Case Study: Risk Analysis for Offshore Wind

The application of the FARO produced the three central results for the methodology’s validation.

First, the baseline risk analysis (

Figure 3) reveals the inadequacy of static assessments. For a “Standard” technology (where

2.0 m), the projected mean downtime fluctuates at an economically critical level (50–70%), indicating economic unfeasibility under this threshold. The comparison between the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios demonstrates a clear exacerbation of risk under the high-emissions scenario, not only in the trend but also in the amplification of interannual variability in the second half of the century. This high variability is, in itself, a financial risk factor, making cash flow unpredictable and increasing project financing and insurance costs.

Second, the results establish that climate risk is not spatially homogeneous (

Figure 4). The risk map for the end of the century (RCP 8.5) elucidates significant spatial heterogeneity. The interpretation of this map is crucial for planning: the ‘hotspots’ (dark red) indicate zones that will compulsorily require higher-resilience technologies (e.g.,

) impacting CAPEX; the ‘corridors’ (yellow/orange), on the other hand, represent strategic opportunities for priority development.

Finally, the sensitivity analysis quantifies the role of technology as the primary adaptation variable (

Figure 5). While the ‘Restrictive’ technology (1.5 m) is unviable (downtime ≈ 100%), the transition from ‘Standard’ (60%) to ‘Flexible’ (2.5 m) results in an order-of-magnitude reduction in risk, with downtime dropping to ≈10%. This result transforms climate adaptation from an abstract concept into a quantifiable investment decision.

5. Discussion

The results from the FARO offer an innovative perspective for the theory and practice of MSP in Brazil and globally, demonstrating that overcoming the stationarity paradigm is methodologically feasible and strategically imperative.

5.1. Techno-Economic Implications: Quantifying the Return on Resilience

The primary implication of the findings is the quantification of the return on investment in resilience. The 50-percentage-point reduction in downtime (

Figure 5) provides an objective metric for planners and investors to compare the additional CAPEX (robust technologies) against the reduction in future OPEX losses. This capability allows for the internalization of climate risk into project valuation models, transforming adaptation from a perceived cost into a strategic value lever [

23]. While direct monetary conversion (e.g., to LCOE) depends on volatile market tariffs and proprietary CAPEX structures, the ‘Downtime’ metric serves as the fundamental, agnostic engineering input that allows any investor to perform financial modeling based on their specific cost parameters.

Therefore, establishing a static monetary conversion model within this article would limit its longevity due to market volatility. Instead, by quantifying the physical driver (downtime), we provide a permanent ‘risk layer’ upon which dynamic economic models can be built by end-users.

5.2. Socioeconomic and Sustainability Implications

The FARO analyses transcend financial viability, touching the core of sustainability objectives [

2]. By “de-risking” offshore renewable energy projects, the framework acts as an enabler for achieving clean energy and climate mitigation goals.

More importantly, it provides a quantitative tool to plan for a “just energy transition” [

42]. A project that fails financially due to unquantified climate risks does not generate the promised local jobs nor develop the regional supply chain. The spatial analysis (

Figure 4), by identifying viable corridors, allows public policies to direct support infrastructure and training programs to coastal communities in these specific areas, ensuring that the socioeconomic benefits of the Blue Economy are distributed more equitably [

10], reducing historical regional inequalities.

5.3. Implications for Public Policy and Adaptive Governance

For MSP practice, FARO offers the analytical basis for dynamic, risk-based zoning. The FARO results are not intended solely for engineers; they are tools for governance dialogue [

16]. The framework provides quantitative data to inform crucial discussions among stakeholders (government, industry, NGOs, local communities) regarding the allocation of marine space [

7]. In practical management terms, the ‘interface’ of the framework operates through its visual decision-support products. The Spatial Risk Map (

Figure 4) serves as a zoning tool for regulators to delineate auction blocks, distinguishing viable development zones from high-risk areas. Simultaneously, for private developers, the Technological Sensitivity Curves (

Figure 5) function as a procurement dashboard, allowing asset managers to determine the necessary vessel class specifications (e.g., standard vs. high-performance SOVs) to meet availability targets before capital is committed. This translation of complex netCDF climate data into intuitive ‘traffic-light’ maps and cost-curves constitutes the core implementation mechanism in real-world planning. For example, a data-informed dialogue could lead to a consensus where ‘hotspots’ (

Figure 4) are prioritized for conservation, while development is incentivized in the lower-risk ‘corridors’.

This allows regulators to modulate development policies according to the geography of future risk, aligning economic growth with climate adaptation. This is the core of “adaptive governance” [

17]: instead of a static plan, FARO allows policymakers to continuously adjust long-term strategies using a dynamic, science-based tool. Such quantitative tools are particularly urgent for Latin America, where recent assessments indicate that despite the progress in coastal management, most nations still lack explicit Blue Economy policies and integrated MSP frameworks [

43].

Although validated with offshore wind, the method is sector-agnostic, and its mathematical core (Equation (1)) is readily adaptable to other Blue Economy sectors. For instance, in Port Logistics, the framework can quantify the risk of ‘channel closure’ (downtime) by setting the wave threshold () to the specific safety limits for pilot boarding operations (typically 2.5 m in exposed terminals). Similarly, in Offshore Aquaculture, the risk metric translates to ‘feeding days lost,’ where thresholds are calibrated to the stability limits of small service barges or the structural fatigue of cages. This flexibility demonstrates FARO’s potential to serve as a unified risk currency, facilitating integrated coastal management across conflicting uses.

Finally, based on these findings, we offer specific recommendations for MSP practitioners to integrate FARO into existing decision workflows: (1) In the Zoning Phase, utilize the Spatial Risk Map (

Figure 4) as a quantitative filter to define ‘exclusion zones’ where operational risk renders development economically unsustainable; and (2) In the Licensing Phase, incorporate the Technological Sensitivity data (

Figure 5) into concession terms, requiring developers to demonstrate that their proposed infrastructure maintains operability under the projected RCP 8.5 scenario. This ensures that public marine space is allocated effectively to projects with verified long-term resilience.

5.4. Synergy with International Methodologies and Scalability

To synthesize the broader applicability of the framework, we address the environmental scope and international synergies of FARO:

Environmental Risks and MSP Scope: While traditional MSP focuses on mitigating environmental risks caused by infrastructure (e.g., biodiversity loss, pollution), FARO addresses the inverse risk: the environmental risks imposed on infrastructure by the climate (waves/wind). By quantifying this Operational Climate Risk, FARO ensures that ‘sustainable development’ encompasses not only ecological protection but also the physical resilience of the energy assets required for decarbonization.

Regional Climate Contribution: At the regional level (Southeastern Brazil), FARO’s contribution lies in Climate Adaptation. Regarding land use, the framework specifically accounts for Marine Space Use (e.g., spatial conflicts with Oil & Gas and Marine Protected Areas) rather than terrestrial land cover changes. This ensures that the regional energy transition is planned within the realistic constraints of the Blue Economy.

Synergy and International Upscaling: As a decision-support instrument, FARO offers distinct benefits when integrated with other methodologies:

Interoperability: The risk probability maps (NetCDF/GeoTIFF) can be directly ingested as cost layers into biodiversity planning software (e.g., Marxan), allowing planners to balance ecological conservation with operational feasibility.

Standardization: By utilizing global industry thresholds (ISO/DNV), the framework allows for the international benchmarking of Brazilian projects, facilitating foreign investment.

Scalability: The source-agnostic architecture permits the upscaling of the analysis to other data-scarce regions (e.g., West Africa or Southeast Asia), employing the same pipeline to support a global Climate-Smart MSP.

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research

This study challenged the anachronistic assumption of climatic stationarity in MSP by introducing FARO, a methodological framework for quantifying adaptive operational risk, validated herein within the specific climatic context of Southeastern Brazil. The analysis indicates that disregarding future climate trajectories leads to a severe underestimation of operational risks, whereas strategic investment in technological resilience offers substantial mitigation potential.

By providing the means to integrate high-resolution climate and technological risk analysis directly into the financial and operational decision-making process, FARO offers a clear, quantitative pathway toward a climate-smart MSP. The contribution of this work is not merely a tool but a proof-of-concept that ocean governance can and must be proactive, evidence-based, and prepared for the challenges of a non-stationary world.

As detailed in the discussion, the next logical steps include the expansion of FARO to CMIP6 multi-model ensembles (after regional downscaling) and to other sectors. In doing so, FARO serves as an essential instrument for stakeholder dialogue and public policy formulation, ensuring the sustainable, equitable, and prosperous development of Brazil’s Blue Economy.

Methodological Limitations and Future Research

The treatment of uncertainty in this study follows a structured approach, prioritizing Scenario Uncertainty (via RCP 4.5 and 8.5 comparisons) and Technological Uncertainty (via operational threshold sensitivity). However, we acknowledge the limitation regarding Model Epistemic Uncertainty. The reliance on a single regional climate driver (INPE-Eta) precludes the quantification of inter-model structural biases, which would require a multi-model ensemble (e.g., CORDEX). As justified in

Section 3.2.3, the choice of a high-resolution regional climate driver was a deliberate methodological trade-off: we prioritized the spatial precision (20 km) necessary for wave modeling over the statistical spread of coarser global ensembles (>100 km). Consequently, the results should be interpreted as a ‘risk projection within the INPE-Eta physics,’ valid for identifying trends and spatial patterns, but subject to the structural limitations of this specific model.

The FARO architecture, being source-agnostic, is ready for the next research step: applying the framework to a CMIP6 ensemble [

31] after it has been subjected to a high-resolution dynamic or statistical downscaling similar to the one validated here. Future research should also focus on applying FARO to other marine industries (aquaculture, port logistics) and in other geographical contexts, especially in the Global South [

13].

Additionally, regarding operational risk components, the current decision function (Equation (1)) evaluates availability on a discrete daily basis. We acknowledge that specific complex maintenance tasks require continuous multi-day weather windows (persistence) and specific sea-state periods. Therefore, risk components not fully captured by the current approach include ‘window fragmentation’ and multi-dimensional constraints (e.g., Mean Wave Period limits). Future developments of the framework will incorporate a ‘Window Persistence Analysis’ module to assess the probability of consecutive operational days, providing a more granular risk profile.

7. Patents

The FARO (Framework for Adaptive Operational Risk Analysis) software, developed as part of this research, has been registered with the Brazilian National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) under registration number BR512025003174-2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.d.P. and T.S.; methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation, J.R.d.P.; validation, J.R.d.P. and T.S.; writing—review and editing, J.R.d.P. and T.S.; visualization, J.R.d.P.; supervision and project administration, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source code that implements the FARO analysis pipeline is publicly available in the FARO-Framework repository on GitHub at

https://github.com/Rinalde-Paulo/FARO-Framework (accessed on 5 November 2025). The repository includes the essential pre-processed auxiliary data files required to run the analysis. The original large datasets for climate projections (ERA5 and CMIP5) are publicly available from their respective official repositories, as cited in the paper.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used the generative AI model Gemini 1.5 Pro. (Google). The tool was used to assist in analyzing the logical flow of the text and structuring the synthesis of arguments within the literature review to enhance their clarity and objectivity. Additionally, it was used for supporting tasks, including drafting the cover letter and conceptualizing the graphical abstract. The authors have critically reviewed, edited, and validated all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santos, C.F.; Ehler, C.N.; Agardy, T.; Andrade, F.; Orbach, M.K.; Crowder, L.B. Marine spatial planning. In World Seas: An Environmental Assessment; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 571–592. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/abs/pii/B9780128050521000334 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Bennett, N.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Blythe, J.; Silver, J.J.; Singh, G.; Andrews, N.; Calò, A.; Christie, P.; Di Franco, A.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; et al. Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milly, P.C.D.; Betancourt, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Hirsch, R.M.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Stouffer, R.J. Stationarity Is Dead: Whither Water Management? Science 2008, 319, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, A.M.; Brink, T.T.; Bas, M.; Sweeting, C.J.; McGuinness, S.; Edwards, H.; Talbot, E.; Sørdahl, P.B.; Lønborg, C.; Deecker-Simon, S.R.; et al. The opportunity for climate action through climate-smart Marine Spatial Planning. npj Ocean Sustain. 2025, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.F.; Agardy, T.; Andrade, F.; Calado, H.; Crowder, L.B.; Ehler, C.N.; García-Morales, S.; Gissi, E.; Halpern, B.S.; Orbach, M.K.; et al. Integrating climate change in ocean planning. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Douvere, F. The engagement of stakeholders in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pınarbaşı, K.; Galparsoro, I.; Borja, Á.; Stelzenmüller, V.; Ehler, C.N.; Gimpel, A. Decision support tools in marine spatial planning: Present applications, gaps and future perspectives. Mar. Policy 2017, 83, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, B.; Clark, A.; Koskelo, K.; Mulholland, E.; Hickey, C. Stranded Assets: Environmental Drivers, Societal Challenges, and Supervisory Responses. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, K.; Gupta, J. Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 56, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorayeb, A.; Brannstrom, C.; Xavier, T.; Soares, M.d.O.; Teixeira, C.E.P.; dos Santos, A.M.F.; de Carvalho, R.G. Emerging challenges of offshore wind power in the Global South: Perspectives from Brazil. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 110, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasnoot, M.; Kwakkel, J.H.; Walker, W.E.; ter Maat, J. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchau, V.A.; Walker, W.E.; Bloemen, P.J.; Popper, S.W. (Eds.) Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Moreno-Báez, M.; Reygondeau, G.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Crosman, K.M.; González-Espinosa, P.C.; Lam, V.W.Y.; Oyinlola, M.A.; Singh, G.G.; Swartz, W.; et al. Enabling conditions for an equitable and sustainable blue economy. Nature 2021, 591, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.P.; Lempert, R.J.; Brown, C.; Hall, J.A.; Revell, D.; Sarewitz, D. Improving the contribution of climate model information to decision making: The value and demands of robust decision frameworks. WIREs Clim. Change 2013, 4, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Pennino, M.G.; Brodie, S.; Frainer, A.; Lopes, P.F.M.; Lopez, J.; Ortega-Cisneros, K.; Selim, S.; Vaidianu, N. The Missing Layers: Integrating Sociocultural Values Into Marine Spatial Planning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 633198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori Nocentini, M. Climate adaptation governance in metropolitan regions: A systematic review of emerging themes and issues. Urb. Clim. 2024, 54, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Jäger, J.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyr, H.; Muskulus, M. Decision Support Models for Operations and Maintenance for Offshore Wind Farms: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsouris, G.; Savenije, L.B. Offshore Wind Access 2017; ECN: Petten, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34629371/3PLZ26/e16013.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Rinaldi, G.; Garcia-Teruel, A.; Jeffrey, H.; Thies, P.R.; Johanning, L. Incorporating stochastic operation and maintenance models into the techno-economic analysis of floating offshore wind farms. Appl. Energy 2021, 301, 117420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, J.; Babovic, V. Adaptation pathways and real options analysis–An approach to deep uncertainty in climate change adaptation policies. Policy Soc. 2016, 35, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuland, M.; Whittington, D. Water resources planning under climate change: Assessing the robustness of real options for the Blue Nile. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2086–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomä, J.; Chenet, H. Transition risks and market failure: A theoretical discourse on why financial models and economic agents may misprice risk related to the transition to a low-carbon economy. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2017, 7, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Deng, K.; Ren, K.; Liu, J.; Deng, C.; Jin, Y. Deep learning in statistical downscaling for deriving high spatial resolution gridded meteorological data: A systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 207, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, C.; Budamala, V.; Kasiviswanathan, K.; Teutschbein, C.; Soundharajan, B.-S. Extreme gradient and boosting algorithm for improved bias-correction and downscaling of CMIP6 GCM data across indian river basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifi, S. Development and Applications of AI for Offshore Wind Power Forecasting. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2024. Available online: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/84539/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Heimbach, P.; O’Donncha, F.; Smith, T.A.; Garcia-Valdecasas, J.M.; Arnaud, A.; Wan, L. Crafting the Future: Machine learning for ocean forecasting. State Planet 2025, 5-opsr, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, H.; Hao, X. Machine Learning-Based Bias Correction of Precipitation Measurements at High Altitude. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPE (Empresa de Pesquisa Energética). Roadmap Eólica Offshore Brasil; Ministério de Minas e Energia (MME): Brasília, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://www.epe.gov.br/pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/roadmap-eolica-offshore-brasil (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2022: População e Domicílios—Primeiros Resultados; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html?edicao=37225 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ANP. Anuário Estatístico Brasileiro do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis 2024; Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anp/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/anuario-estatistico/anuario-estatistico-brasileiro-do-petroleo-gas-natural-e-biocombustiveis-2024 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ICMBio. Painel Dinâmico de Unidades de Conservação; Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/paineis-dinamicos-do-icmbio (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Min, S.-K.; Zhang, X.; Sillmann, J.; Sandstad, M. Evaluation of the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble for climate extreme indices. Weather Clim. Extremes 2020, 29, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.C.; Lyra, A.; Mourão, C.; Dereczynski, C.; Pilotto, I.; Gomes, J.; Bustamante, J.; Tavares, P.; Silva, A.; Rodrigues, D.; et al. Assessment of Climate Change over South America under RCP 4.5 and 8.5 Downscaling Scenarios. Am. J. Clim. Change 2014, 3, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra, A.; Tavares, P.; Chou, S.C.; Sueiro, G.; Dereczynski, C.P.; Sondermann, M.; Silva, A.; Marengo, J.A.; Giarolla, A. Climate change projections over three metropolitan regions in Southeast Brazil using the non-hydrostatic Eta regional climate model at 5-km resolution. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 132, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, A.J.; Sobie, S.R.; Murdock, T.Q. Bias Correction of GCM Precipitation by Quantile Mapping: How Well Do Methods Preserve Changes in Quantiles and Extremes? J. Clim. 2015, 28, 6938–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard DNV-ST-N001; Marine Operations and Marine Warranty. Det Norske Veritas: Høvik, Norway, 2021. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/energy/standards-guidelines/dnv-st-n001-marine-operations-and-marine-warranty/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Heleno, M.; Sigrin, B.; Popovich, N.; Heeter, J.; Figueroa, A.J.; Reiner, M.; Reames, T. Optimizing equity in energy policy interventions: A quantitative decision-support framework for energy justice. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T. Integration of Marine Spatial Planning into Blue Economy Policies in Latin America. Mar. Policy 2025, 171, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).