Against the backdrop of intensifying global climate change and resource and environmental constraints, advancing sustainable development has become a paramount global mission. In this context, governments worldwide are actively exploring and implementing diverse environmental policies to steer enterprises toward green transformation and sustainable development. To further advance high-quality development goals for a comprehensive green transition of the economy and society, the Chinese government has proposed a coordinated approach. Guided by the “Dual Carbon Goals” (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality)—a cornerstone of its national sustainability strategy—this approach synergizes carbon emission reduction, pollution control, green initiative expansion, and economic growth. This approach entails deepening institutional reforms for ecological civilization and strengthening green, low-carbon development mechanisms. As primary actors in the market economy and key contributors to sustainable value creation, enterprises represent the core driving force for achieving high-quality development in a modernized economic system. Simultaneously, enterprises are key stakeholders in realizing pollution and carbon reduction targets. Stringent environmental regulations, while designed to promote environmental sustainability, compel firms to internalize the externalities of environmental pollution, inevitably increasing their operational costs and posing challenges to their economic sustainability.

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

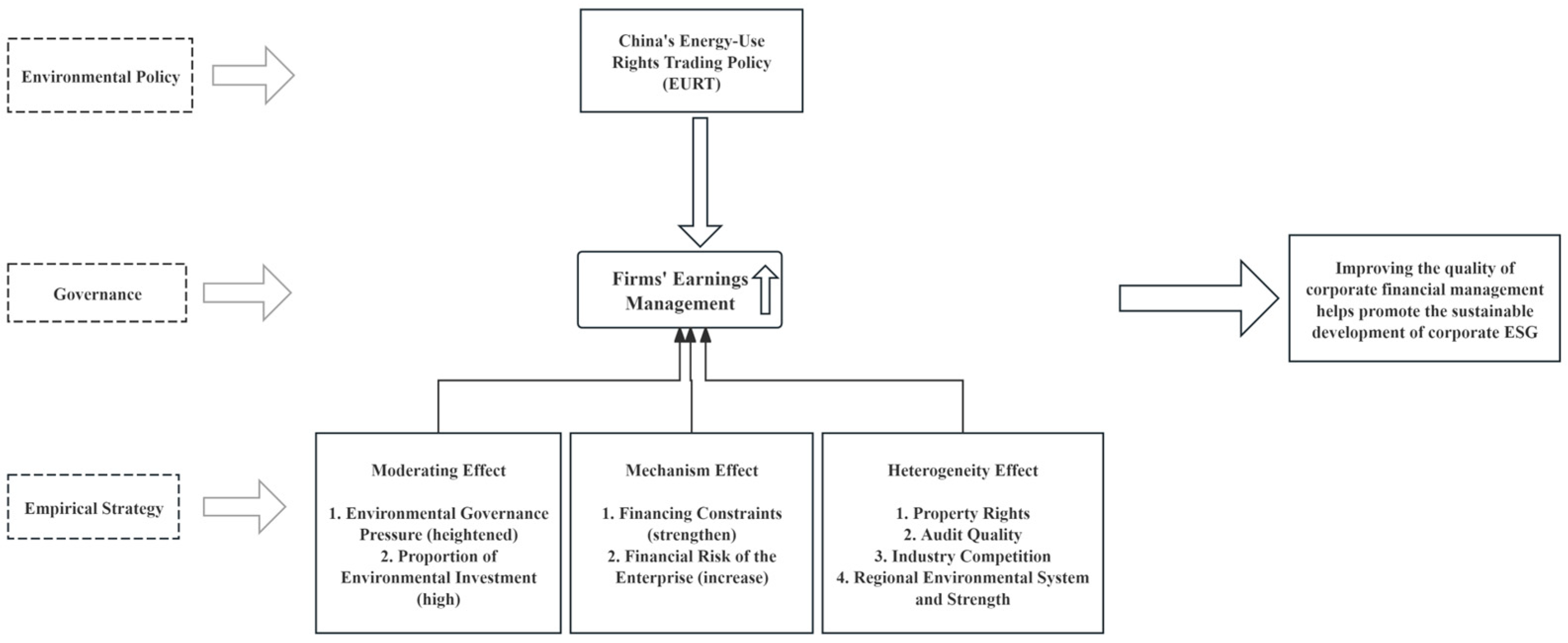

Common environmental regulations mainly include command-and-control environmental regulations and market-based environmental policies. While carbon trading policies—focused on end-of-pipe emission reduction—are advancing vigorously, the Energy-Use Rights Trading (EURT) policy—targeting front-end energy conservation as a more fundamental approach to sustainable resource use—is being piloted systematically across China. Since 2016, provinces including Zhejiang, Fujian, and Henan have pioneered the pilot implementation of the EURT system. This institutional innovation marks a major shift in China’s front-end energy conservation policies from traditional command-and-control models (e.g., the dual-control targets for energy consumption) toward market-based emission reduction instruments. It aims to resolve the dual dilemma of “energy constraints vs. economic growth” through market mechanisms, seeking a sustainable pathway that harmonizes ecological preservation with economic vitality. Earnings management refers to corporate profit manipulation through accounting policy choices and estimation adjustments, driven by profit maximization or market value management objectives. It primarily encompasses accrual-based manipulation and real-activity manipulation. Such practices directly undermine corporate governance transparency and financial integrity, which are pillars of long-term economic sustainability and investor confidence. The core of the EURT policy lies in the front-end control of corporate energy consumption. Within the framework of “rational quota allocation—standardized trading and strict compliance mechanisms,” enterprises may buy or sell energy-use rights quotas to conserve energy or generate revenue. In this process, highly energy-efficient enterprises may generate surplus quotas, allowing them to sell these for additional income. Enterprises with insufficient quotas must purchase other quotas to meet production needs or enhance energy efficiency through innovation and production line upgrades, which may strain short-term financial sustainability. The EURT policy may incentivize R&D investment but simultaneously increases costs (e.g., to avoid over-consumption penalties), thereby creating motives for earnings management. Such managerial behavior could harm stakeholders’ interests and state tax revenues while undermining the integrity of corporate sustainability reporting and long-term enterprise value. A critical question arises: While market-based environmental regulations such as EURT achieve ecological protection, they also burden enterprises—do firms resort to earnings management in response, thereby compromising governance and economic dimensions of sustainability? Consequently, examining the impact of EURT on corporate earnings management holds significant practical relevance for designing holistic sustainability policies that avoid detrimental side effects.

1.2. Research Objectives and Contributions

Existing research primarily focuses on the positive impacts of market-based environmental policies (e.g., EURT and carbon emission trading (CET)) on macro-level environmental performance—such as reducing regional carbon emission intensity and optimizing energy structures [

1,

2,

3]—and corporate environmental behavior, such as enhanced green innovation and improved green total-factor energy efficiency [

4,

5,

6]. These studies affirm the instrumental role of such policies in advancing environmental sustainability. However, the impact of environmental policies on sustainability at the micro-enterprise level exhibits complexity and multifaceted dimensions. Increasing compliance costs, technological upgrading demands, and potential penalty risks induced by policy implementation may profoundly impact corporate financial conditions and operational decisions, thereby triggering trade-offs between environmental, economic, and governance sustainability.

Notably, how environmental policies—as major external institutional shocks—affect corporate accounting information quality, particularly earnings management behavior, which is a critical aspect of corporate governance (the ‘G’ in ESG), has not been fully explored. Enterprises’ internal and external environments—such as governmental reforms [

7], green density [

8], the role of independent directors [

9], and debt covenant pressure [

10]—are critical factors influencing their earnings management incentives. Against pervasive information asymmetry and agency conflicts, management may engage in earnings management for diverse motives (e.g., financing needs, risk avoidance). The cost pressures, investment requirements, and compliance risks introduced by the EURT policy are likely to significantly alter firms’ financial incentives and constraints, thereby influencing their motivations and capacity for earnings management. For instance, financing constraints exacerbated by cost shocks or green fund investments or the elevated financial risks arising from policy uncertainty may prompt management to manipulate earnings to embellish financial statements, secure external financing, or circumvent financial distress. This creates tension between the policy’s environmental objectives and its potential negative effects on corporate financial transparency.

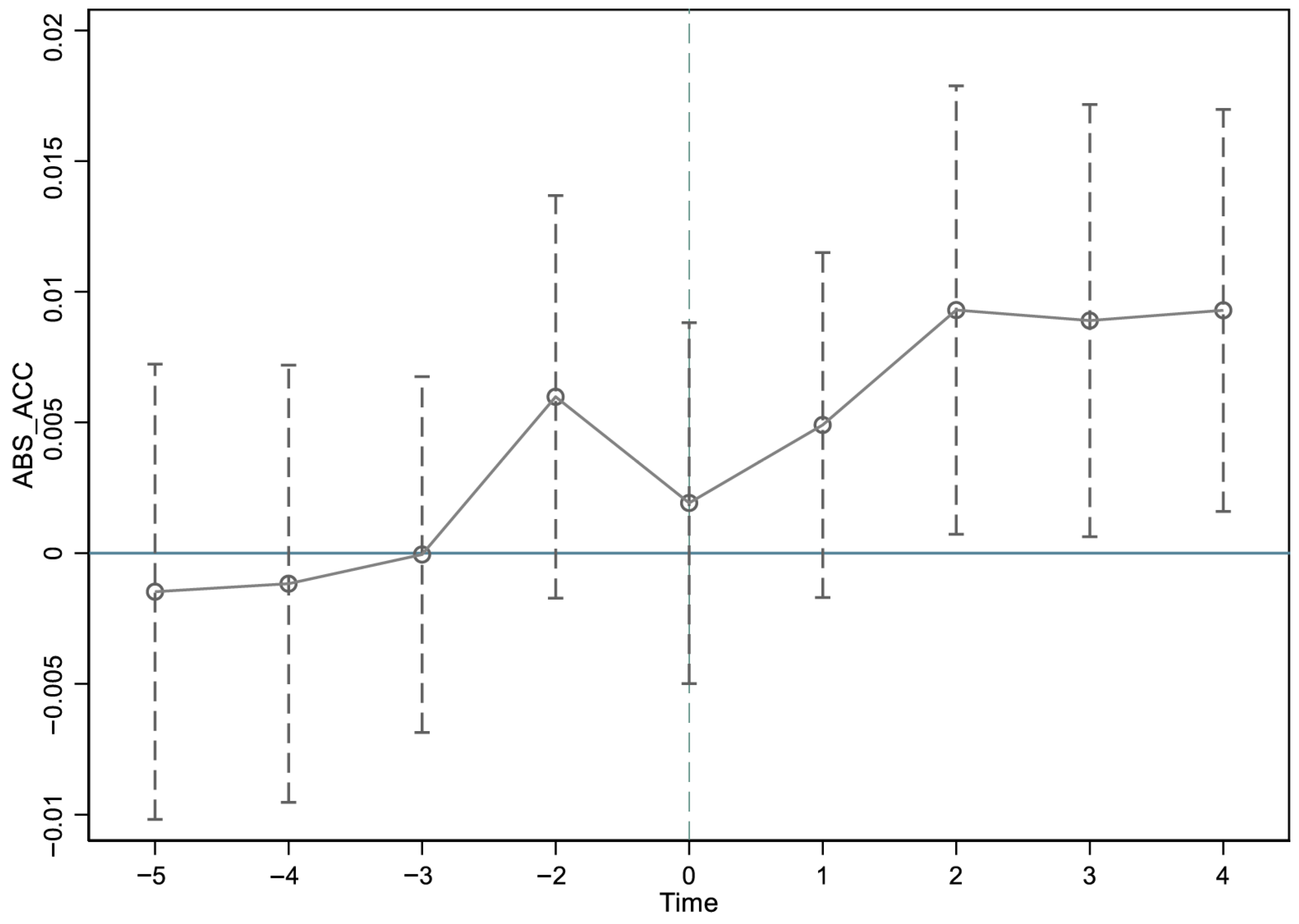

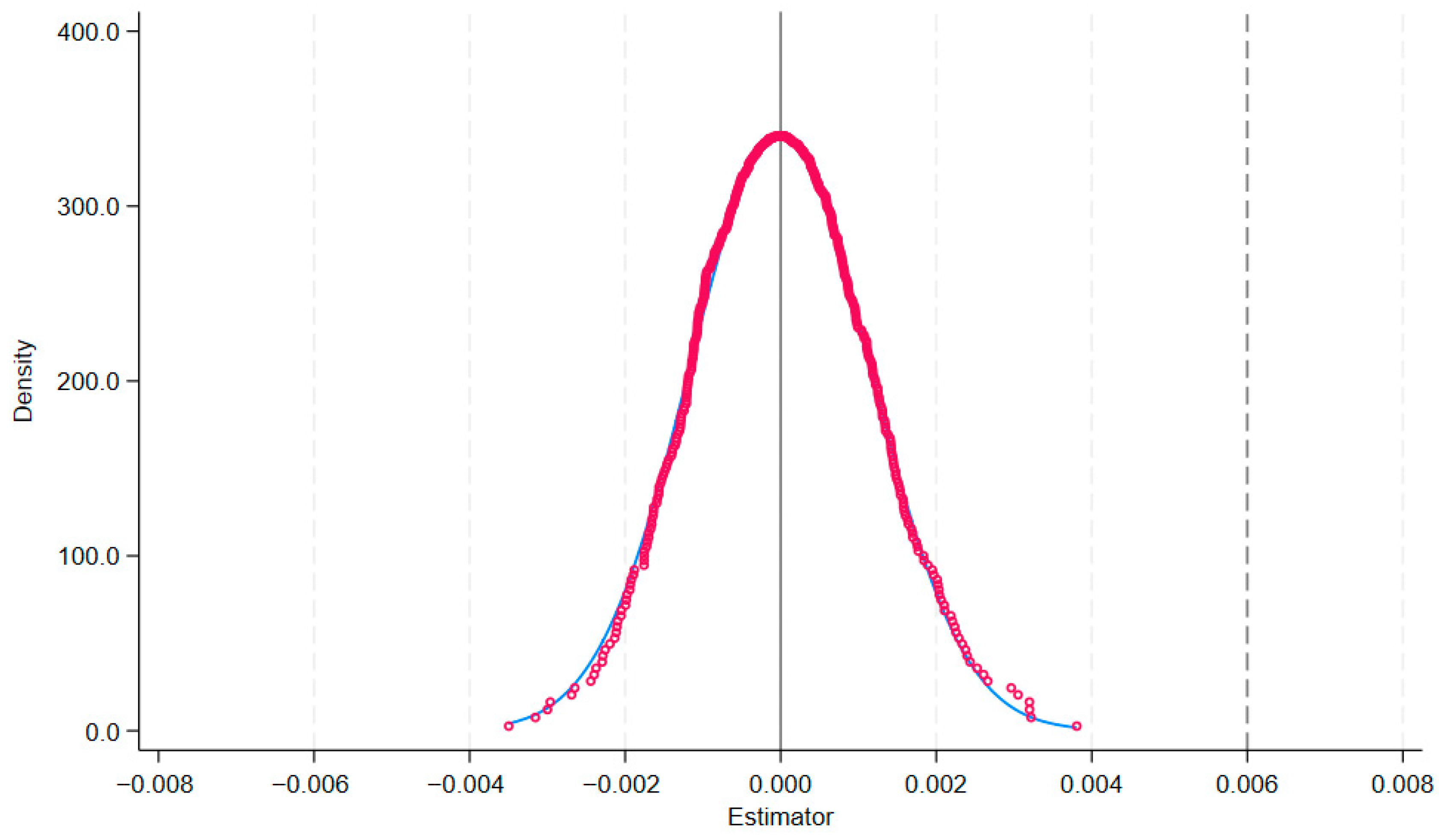

The core purpose of this study is to explore the potential impact and internal mechanism of market-based environmental regulation policies represented by EURT on the microeconomic behavior of enterprises represented by “earnings management”. Using micro-data from China’s A-share listed companies from 2010 to 2022, this study answers the following critical question: Does the EURT policy, by increasing environmental compliance costs and financial risks, prompt firms to engage in earnings management, thereby undermining corporate governance and information quality—key pillars of sustainable development? Our findings aim to provide an empirical basis for designing integrated sustainability policies that balance environmental, economic, and governance objectives. Our empirical findings reveal the following: (1) Following the implementation of the EURT policy, earnings management intensity is significantly higher in pilot-region firms than in non-pilot firms. (2) This effect is more pronounced in private enterprises, non-Big-Four-audited firms, firms in highly concentrated industries, and firms located in regions with lower environmental fiscal expenditure and weaker waste gas treatment capacity, highlighting how heterogeneous corporate governance structures and regional institutional capacities influence the sustainability policy outcomes. (3) Environmental governance pressure amplifies the policy’s positive effect on earnings management, whereas a high proportion of environmental investment significantly mitigates it, suggesting potential levers for achieving better synergy between environmental and economic sustainability. (4) Mechanism analysis confirms that the policy elevates earnings management through dual channels: by intensifying financing constraints and increasing financial risk.

This study contributes to the existing literature in the following three key aspects: First, our research perspective is innovative. While the existing literature has extensively examined the economic and environmental impacts of environmental policies, little attention has been focused on their potential effects on accounting information quality—a core element of corporate governance. By examining the EURT policy as a significant external shock influencing corporate earnings management, this study enriches the interdisciplinary field that bridges the economic consequences of environmental regulations and micro-level accounting behavior while also introducing a governance dimension to the assessment of sustainability policies. This study expands the ESG framework by incorporating the corporate governance (G) dimension into the assessment of sustainable policies, which have traditionally focused on environmental (E) and social (S) outcomes. This sheds light on the potential tension between energy trading policies and corporate governance transparency. Second, this study demonstrates considerable depth in its mechanistic analysis. It moves beyond a superficial description of the phenomenon to dissect the precise pathways through which the Energy-Use Rights Trading (EURT) policy influences corporate behavior, pinpointing “the intensification of financing constraints” and “the elevation of financial risk” as the two core mechanisms. It is through these two channels that the energy rights trading policy significantly changes the financial incentives and constraints of management by influencing the financing constraints of enterprises and increasing financial risks. This dual effect reinforces their motivation and capacity to engage in earnings management to embellish financial statements, secure financing, or avoid financial distress, revealing the micro-level channels through which sustainability policies can inadvertently strain corporate economic resilience and reporting integrity. Third, this study provides rigorous empirical validation. Based on a robust empirical framework, we offer compelling empirical evidence supporting the theoretical mechanisms above, thereby providing valuable insights for policymakers aiming to refine sustainability instruments to foster truly integrated and robust sustainable development. At the same time, through detailed heterogeneity analysis (such as the nature of enterprise property rights, audit quality, industry competition, regional institutional environment, etc.), the differences in policy effects in different scenarios are revealed, rendering the conclusions more convincing and providing policy reference value.