Walking and Time! The Style of Walkability in Urmia Old Town

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To analyze the spatial transformation of Urmia between 1933 and 2018 using key Space Syntax indicators, and to assess the impact of the transition from organic to grid-based urban patterns on spatial accessibility;

- To examine the relationship between these structural transformations and the evolving patterns of pedestrian movement and public space use within the historic Bazaar core, and to evaluate its resilience to modern urban interventions;

- To provide practical insights for heritage-oriented urban planning and walkability enhancement, with an emphasis on preserving spatial coherence, promoting social equity, and supporting environmental and economic sustainability.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Review of Recent Studies

2.2.1. George Town, Penang [13]

2.2.2. Varanasi, India [11]

2.2.3. Directions in Space Syntax [45]

- Improving the predictive accuracy of statistical models;

- Advancing descriptive and exploratory measures;

- Developing design-support tools for planners.

2.2.4. Synthesis of the Literature and Key Observations

3. Methodology

- Normalized Axial Integration (NAI):

- 2.

- Normalized Axial Choice (NAC):

- The meaning of ‘Integration’ as well as NAI as a measure for describing the pedestrian movement (can be read as walking passes) and as the normalized index of distance from each origin space, calculating how close the origin is to other spaces, which can be read as how the spaces have been used [9,50,51].

- The meaning of ‘Choice,’ as well as NAC, as a syntactic measure, represents the potential for local movement of residents and serves as an indicator of how frequently a street segment may be used through all routes from all spaces to others, accounting for pedestrian route distances, which can be interpreted as the centrality of the spaces [9,50,51].

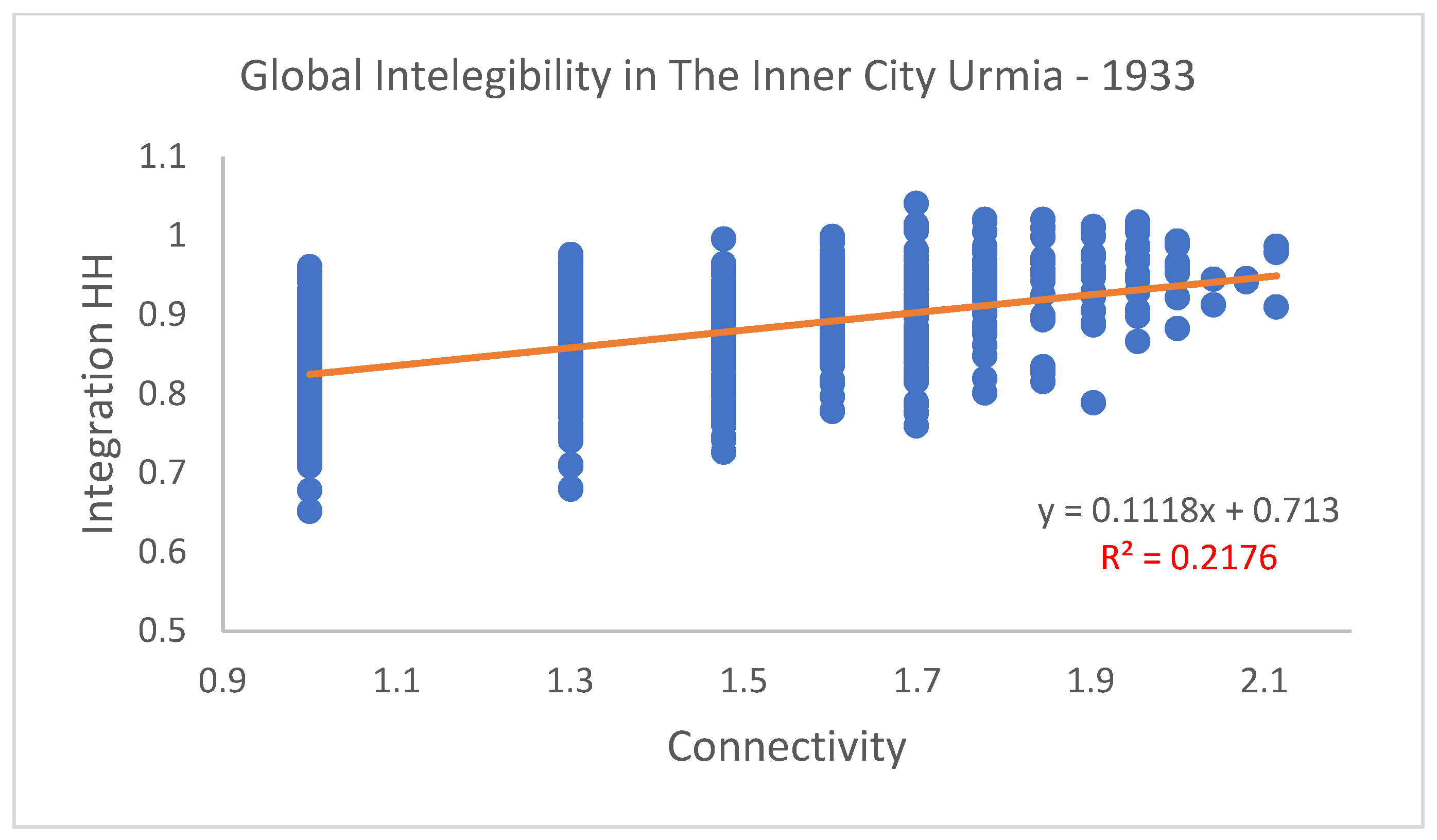

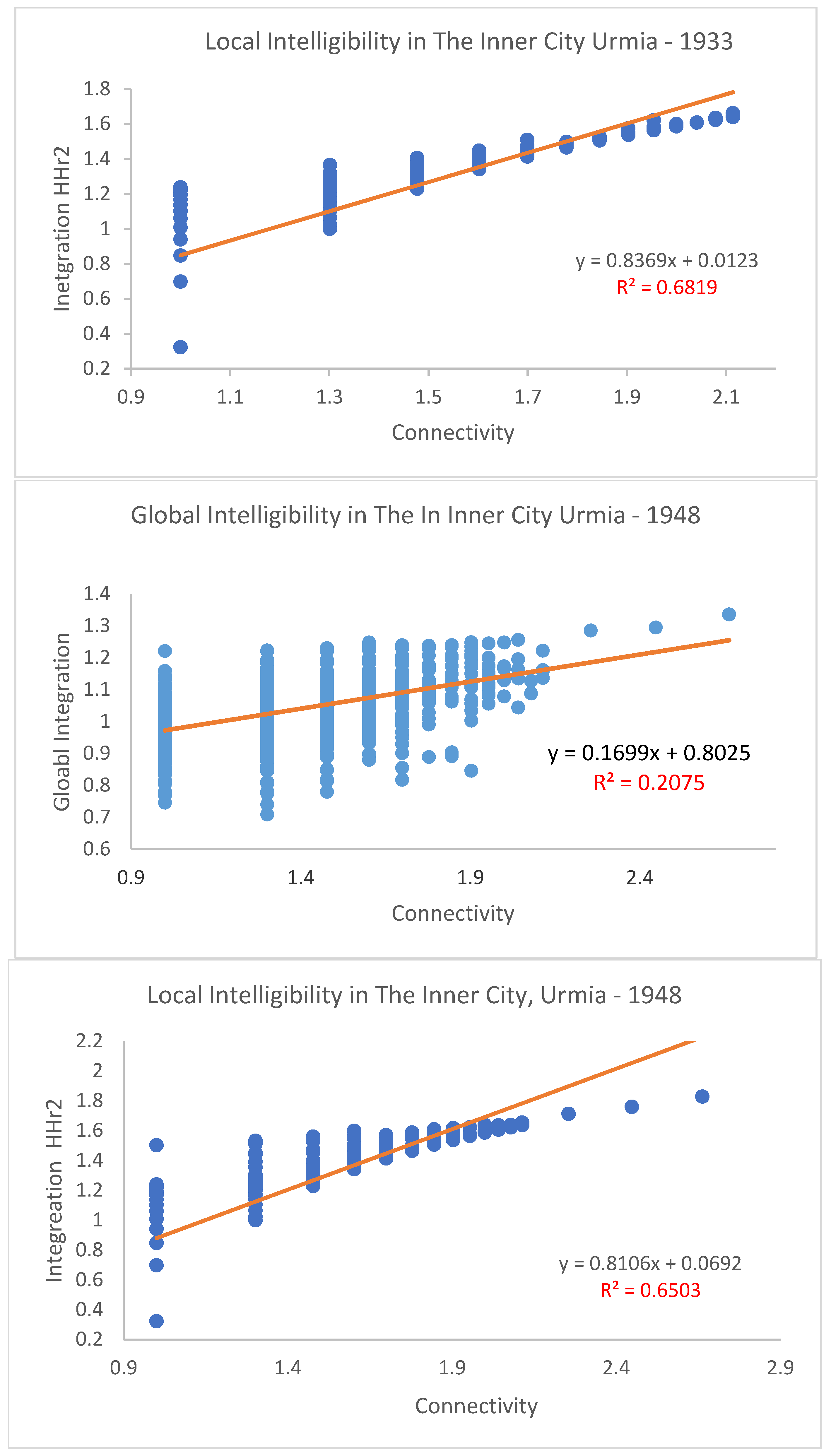

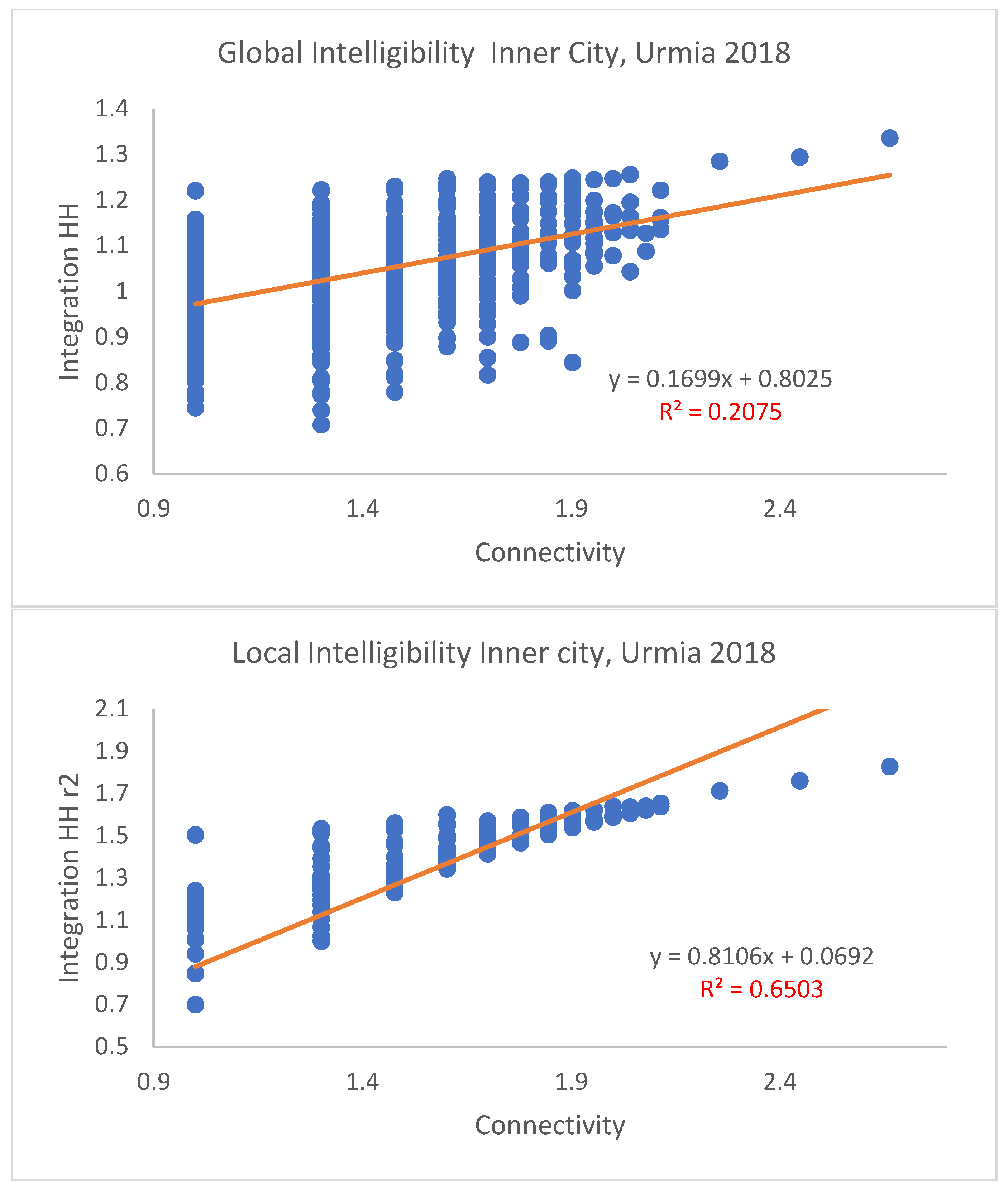

- The meaning of ‘Intelligibility’ as a measure expressing the relationship between local and global integration (R2), reflecting the legibility and perceptual coherence of the urban form. It indicates how easily the overall spatial layout of a city can be understood from its local structure. Higher R2 values represent a more legible and cognitively understandable network, whereas lower values indicate spatial fragmentation and difficulty in wayfinding [35,53].

4. Case Study Area

5. Analysis and Results

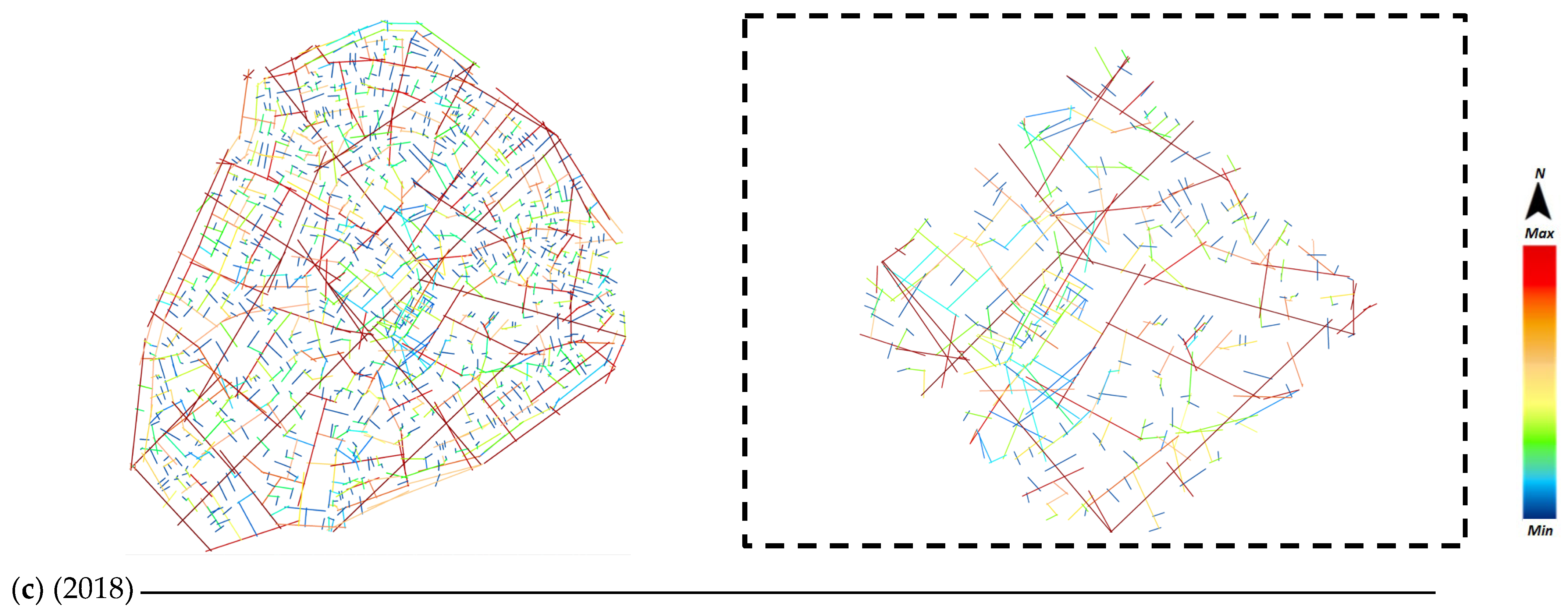

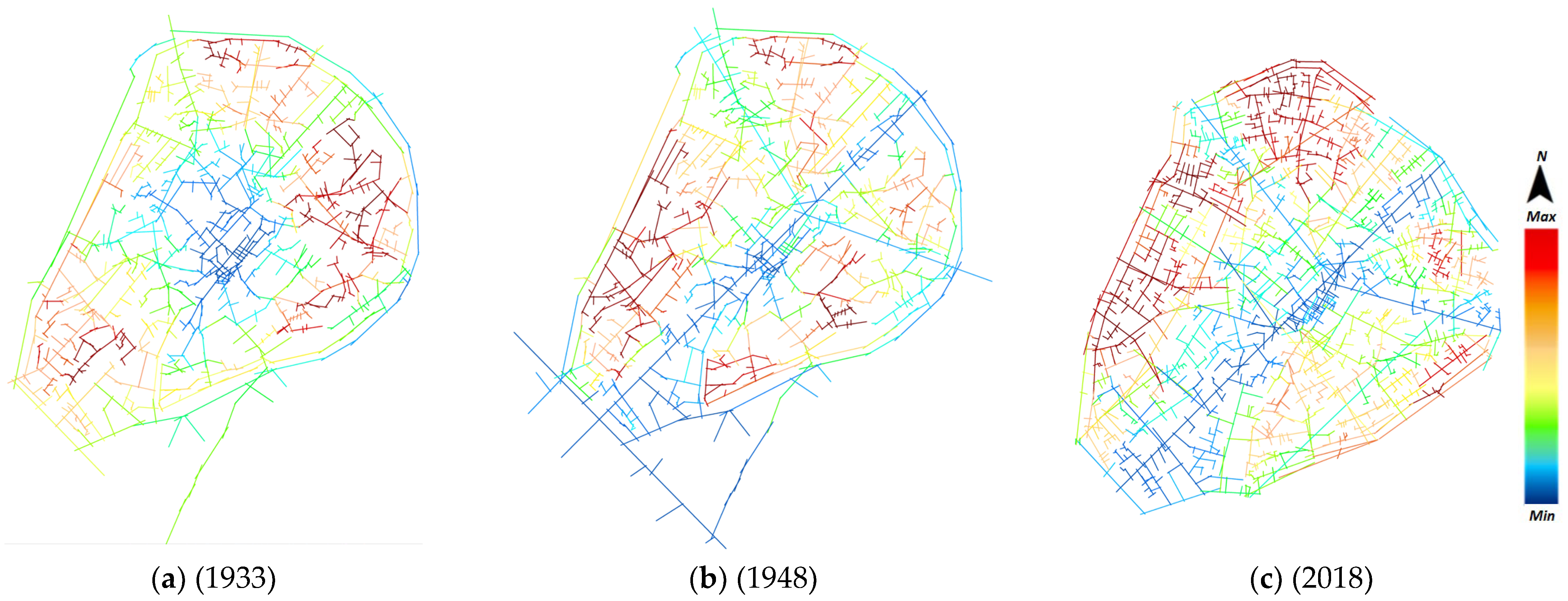

5.1. Spatial Configuration of Urmia

5.2. Changes in Pedestrian Mobility and Network Expansion

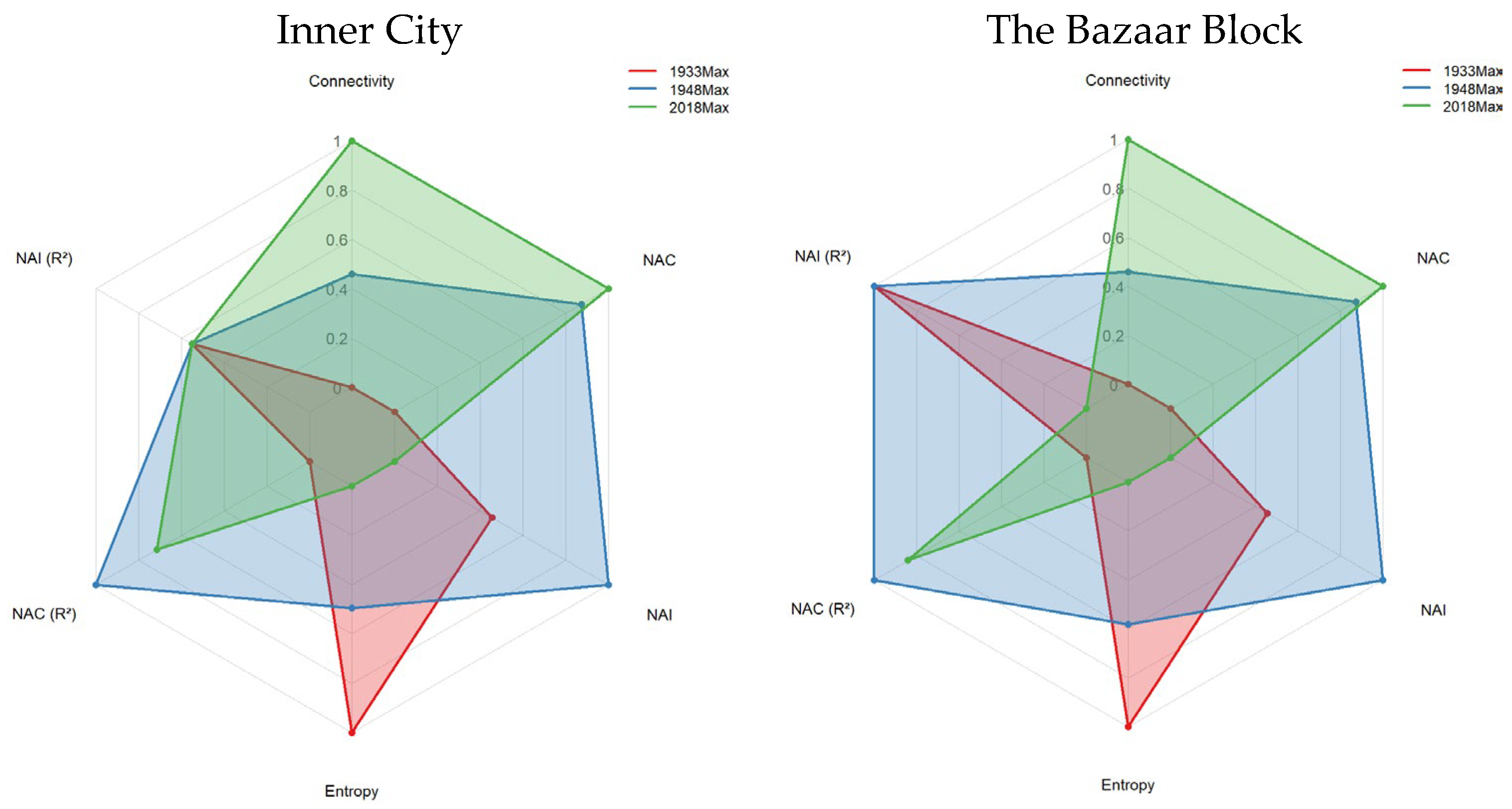

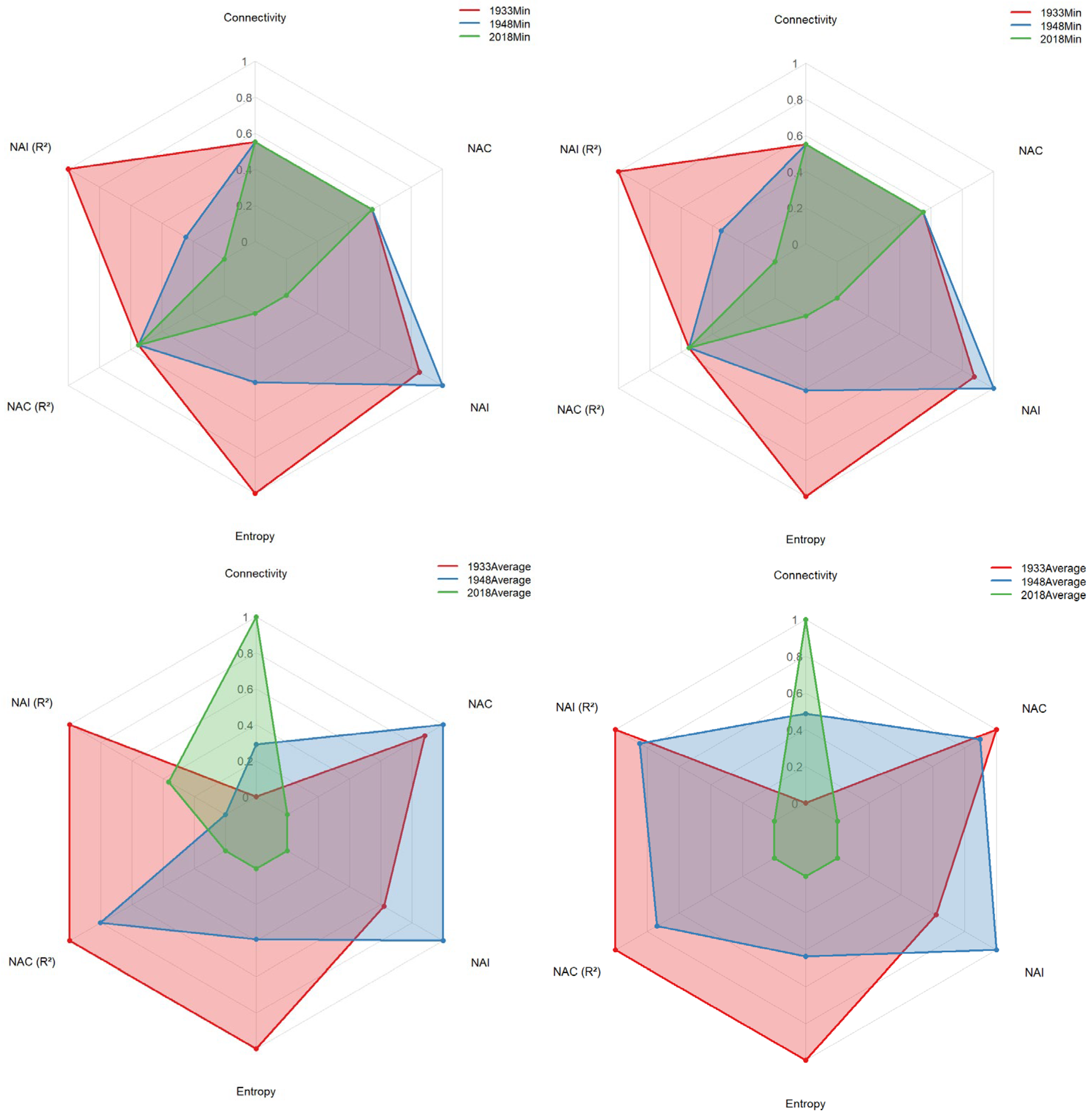

5.3. Comparative Findings Across Three Periods

5.4. Entropy and the Shift in City Structure

5.5. Intelligibility and Legibility of Urban Form

- Monocentric Core and Bazaar’s Role: Urmia is fundamentally a monocentric city with a highly dense inner core. The Bazaar, as one of the oldest urban fabrics, functions as a powerful economically attractive center and is exceptionally well-connected to its surroundings. Spatial analysis consistently shows the Bazaar public space as one of the most used spaces throughout the analyzed periods.

- Impact of Modernization: While new streets imposed during modernization changed the distribution of walking spaces from centric to linear, the old town, particularly the Bazaar, still maintains an important role.

- Increased Mobility and Connectivity: Global measures of Topological analysis of NAC and NAI, which reflect user-friendliness and the possibility of pedestrians choosing certain paths, have increased over time. This indicates the growing importance and increased use of the city center’s spaces.

- Bazaar’s Continuing Importance: spaces within the Bazaar block were consistently more used and chosen by pedestrians over time.

- Shift in City Structure (Entropy): The entropy measure, which indicates the distribution and coherence of spaces, decreased in the inner city. This suggests a change from a monocentric to a linear-centric structure, though the old construction still influences the city’s layout.

- Socialization and Commercial Activities: The “Choice” measure confirms increased mobility through the Bazaar block and inner city, even in recent years. “Integration” suggests that people choose routes through streets where others pass, fostering socialization, and these routes often coincide with the Bazaar’s commercial areas.

- Improved Accessibility and Mobility: Despite new urban layouts changing the coherence and connection of the Bazaar to its neighboring spaces, the new streets appear to have improved accessibility and improved people’s mobility through public spaces. This also indicates that more spaces are being selected by people in their daily journeys, leading to more social and economic activities in public spaces.

- Bazaar’s Dynamic Role: This study concludes that the Bazaar and inner city, as a core space in the former fabric, continues to facilitate significant pedestrian movement along its primary routes and pathways, leading to greater public presence. The axial map analysis confirms that the Bazaar maintains its dynamic role over time, even as the city transitions from a monocentric to a more linear structure.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Prioritize Historic Cores: Recognize and enhance historic centers as dynamic, functional pedestrian hubs rather than bypassing them. Planning efforts should focus on improving connectivity to and within these areas.

- Integrate Thoughtfully: Design new urban and transportation networks to complement and funnel movement towards existing vibrant centers, ensuring seamless and continuous pedestrian pathways that link old and new urban fabrics.

- Align Land Use with Spatial Design: Develop strategic land-use policies that co-locate attractions along highly integrated pedestrian routes. This ensures that spatial potential is actualized into vibrant public life and economic activity.

- Utilize Space Syntax for Planning: Employ Space Syntax not just for diagnostic analysis but also as a predictive tool to model the impact of proposed changes on pedestrian flow, accessibility, and spatial character. This enables evidence-based, heritage-sensitive planning.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s) & Year | Primary Focus/Contribution | Key Concepts/Findings | Relevance to Walkability & Space Syntax |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework | |||

| Hillier and Hanson [9], Hillier, Pen, Hanson, Xu and Grajewski [10] | Established Space Syntax as a method for spatial analysis/modeling. | Introduced “natural movement” theory, linking urban form, function, transformation, and pedestrian activity. | Foundational work defining Space Syntax and its application to understanding urban movement patterns. |

| Batty [15] | Defined urban “big data” and its implications for city management. | Emphasized urban data’s spatial and temporal tagging; highlighted its potential for understanding urban dynamics across time. | Connects the availability of “what happens where and when” data in cities to urban management, laying groundwork for data-driven walkability analysis. |

| Gomes [16]; Hillier & Hanson [9]; Hillier & Iida [17]; Madanipour et al. [18]; Penn et al. [19] | Discussion on public spaces, accessibility, urban dynamics, human behaviors, and interactions. | Clearly accepted strong linkage among public spaces, human activities, and the ways people interact with them. | Reinforces the importance of public space design and its direct link to human activity and walkability. |

| Gehl [22]; Kostof [23] | Outdoor activities in medieval cities and urban makeover. | Streets and squares designed to support residences’ activities and passageways; ordered pedestrians. | Historical perspective on urban design’s influence on pedestrian movement and public life. |

| Jacobs [24] | Modernist look at urban fabric, variety of activities in streets, block size effects. | Short blocks lead to more accessibility, activities, social interactions, and walking/pedestrian spaces. | Emphasizes block size as a key urban design element impacting walkability and social interaction. |

| Katz [25] | New Urbanism design guidelines. | Emphasizes pedestrian streets and mixed-use neighborhoods to integrate vitality in cities. | Highlights contemporary urban planning principles that prioritize walkability and mixed uses. |

| Giles-Corti et al. [27] | Defined walkability as a main factor illustrating pedestrian presence. | Degree to which built environment supports walking, encouraging social and health benefits. Complex concept encompassing physical, social, and cultural factors. | Provides a comprehensive definition of walkability, underscoring its multifaceted nature beyond mere physical infrastructure. |

| Cervero & Kockelman [28] | Defined walkability regarding public space pedestrian-friendliness. | Includes features like sidewalk continuity, street connectivity, safe crossings, public transit access, and other physical activity encouragement. | Details specific physical features that contribute to walkability, often quantifiable in Space Syntax studies. |

| Van Nes [34] | Stressed Space Syntax’s success. | “Concise definition of space and a high degree of falsifiability and testability.” Confirmed Space Syntax’s philosophy and methodology for examining social behavior, actions, and spatial configuration. | Explains the underlying strengths and empirical rigor of Space Syntax methodology. |

| Hillier [35]; Hillier et al. [10]; Penn et al. [19] | Space Syntax philosophy and methodology regarding social behavior and spatial configuration. | Examined the relationship of social behavior, actions, and spatial configuration. | Reaffirms the core premise of Space Syntax: that spatial layout influences social patterns. |

| Carr et al. [36]; Jacobs [24] | Walkability as a key factor in urban design and planning. | Refers to how far an environment encourages pedestrian movement and facilitates walking. | Reinforces walkability as a fundamental concept in urban design. |

| Hillier [35]; Turner [40] | Space Syntax theory on spatial configuration’s impact. | Significant impact on walkability, social interaction, economic activity, and environmental sustainability. | Broadens the scope of Space Syntax’s influence beyond just movement to include wider urban performance. |

| Lin & Ban [38]; Porta et al. [39] | Space Syntax analysis for understanding spatial properties affecting walkability. | Density and connectivity of street network, accessibility and visibility of public spaces, proximity and diversity of destinations. | Identifies specific spatial properties analyzed by Space Syntax that directly influence walkability. |

| Lin & Ban [38]; Turner et al. [40]; Ye et al. [41] | Space Syntax analysis revealing interconnections and informing urban design. | Can reveal how different parts are interconnected, how people move/interact, and help identify barriers to walkability. Informs strategies for pedestrian-friendly environments. | Demonstrates the practical application of Space Syntax in identifying walkability issues and guiding design interventions. |

| Hillier & Hanson [9] Donegan et al. [43] | Syntactic measures: Permeability (Integration & Choice). | Integration: Potential to movement, accessibility for visitors/pedestrians. Choice: Potential through movement, betweenness, often chosen as shortcut/bypass, related to residents’ flow. | Defines the two primary Space Syntax measures (Integration and Choice) and their relevance to different types of pedestrian movement. |

| Review of Recent Studies | |||

| Fan et al. [13] George Town, Penang | Improving pedestrian accessibility and safety in a historic city. | Used axial and segment mapping, DepthmapX to analyze connectivity, integration (local, 400 m), intelligibility, and choice. Identified poor network connectivity, inadequate access to attractions, suboptimal intelligibility (R2 = 0.593). Simulations showed improvements. | Empirically applies Space Syntax to a real-world urban planning problem, demonstrating its utility in assessing and improving pedestrian environments in historic contexts. Highlights intelligibility as a key challenge in complex layouts. |

| Nag et al. [11]-Varanasi, India | Measuring connectivity of pedestrian street networks. | High correlation between Normalized Angular Integration (NAIN) and pedestrian volume (r = 0.57, p = 0.012). MLR and path models confirmed relationship with NAIN, ROW, sidewalks, and commercial area. Very low intelligibility (0.014). | Provides empirical evidence for the predictive power of Space Syntax (NAIN) on pedestrian volume, especially when combined with built environment features. Emphasizes the critical issue of poor wayfinding in organically developed cities. |

| Stavroulaki [45]-Directions in Space Syntax | Broader perspective on Space Syntax evolution and future directions for sustainable urban development. | Argues for Space Syntax’s capability to model pedestrian flows. Highlights increased predictive power with empirical data (Wi-Fi signals), built density, and accessibility to attractions. Angular centrality explains pedestrian distribution (up to 65%), but built density stronger for absolute volume. Lower angular thresholds (10–20°) correlate strongly with flows. | Offers a meta-analysis of Space Syntax’s predictive capabilities, emphasizing the importance of combining configurational measures with land use and density data for more robust models. Points to the challenge of optimizing street network representation. |

| Synthesis of Literature and Key Observations | |||

| (Consistent across studies) | Application and empirical validation of Space Syntax measures. | Integration and Choice consistently effective measures for quantifying pedestrian potential and flow. | Confirms the robustness and wide acceptance of Integration and Choice as core Space Syntax metrics in walkability research. |

| (Varanasi & Stavroulaki) | Relationship between Space Syntax, pedestrian volume, and built environment features. | While spatial layout is foundational, actual pedestrian volume and quality are significantly influenced by physical infrastructure (sidewalks, ROW) and land-use (commercial areas). | Advocates for a holistic approach to urban planning for walkability, integrating configurational design with practical infrastructure and strategic land-use planning. |

| (George Town & Varanasi) | Consistently suboptimal intelligibility scores in historic, organically developed cities. | Implies that complex, irregular layouts can be difficult to navigate for unfamiliar users, even if highly integrated or chosen for movement. | Identifies intelligibility as a crucial, often overlooked, aspect of walkability in historic urban environments, suggesting a need for interventions that enhance spatial legibility. |

References

- Maniei, H.; Askarizad, R.; Pourzakarya, M.; Gruehn, D. The Influence of Urban Design Performance on Walkability in Cultural Heritage Sites of Isfahan, Iran. Land 2024, 13, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafka, E.; Biraghi, C.A. Walkability: From Spatial Analytics to Urban Coding and Actual Walking. Urban Plan. 2025, 10, 10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, L.; Holec, K.; Escher, T. Socio-Spatial Justice through Public Participation? A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Distributive Justice in a Consultative Transport Planning Process in Germany. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 20, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Rebecchi, A.; Manfredini, F.; Ahlert, M.; Buffoli, M. Promoting Public Health Through Urban Walkability: A GIS-Based Assessment Approach, Experienced in Milan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenhöfer, J.; Nouri, E.; Reschke, M.L.; Seebach, F.; Buchcik, J. Walkability and Urban Built Environments—A Systematic Review of Health Impact Assessments (HIA). BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stutz, P.; Kaziyeva, D.; Traun, C.; Werner, C.; Loidl, M. Walkability at Street Level: An Indicator-Based Assessment Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.D.G.; Mourato, J.; Sousa Vale, D. Uncovering Walkability: A Chronological Literature Review. Transp. Rev. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, P.Y.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, Y. Walkability Assessment in a Rapidly Urbanizing City and Its Relationship with Residential Estate Value. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; ISBN 978-0-521-36784-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Penn, A.; Hanson, J.; Grajewski, T.; Xu, J. Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement. Environ. Plann B Plan. Des. 1993, 20, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.; Sen, J.; Goswami, A.K. Measuring Connectivity of Pedestrian Street Networks in the Built Environment for Walking: A Space-Syntax Approach. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2022, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J.; Graham, H. Ideas Are in Things: An Application of the Space Syntax Method to Discovering House Genotypes—B Hillier, J Hanson, H Graham, 1987. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1987, 14, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Abdullah, A.; Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J. Using a Space Syntax Approach to Enhance Pedestrians’ Accessibility and Safety in the Historic City of George Town, Penang. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L.; Peponis, J.; Dalton, R.C. (Eds.) Space Syntax: Selected Papers by Bill Hillier; UCL Press: London, UK, 2025; pp. 1–679. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. Big Data, Smart Cities and City Planning. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2013, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P. Public Space and the Challenges of Urban Transformation in Europe, Edited by Ali Madanipour, Sabine Knierbein and Aglaée Degros, New York and London, Routledge, 2014, Xi + 217 pp., £27.99 (paperback), ISBN 978-0-415-64055-8. Urban Res. Pract. 2014, 7, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Iida, S. Network and Psychological Effects in Urban Movement. In Proceedings of the Spatial Information Theory, Ellicottville, NY, USA, 14–18 September 2005; Cohn, A.G., Mark, D.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A.; Knierbein, S.; Degros, A. Public Space and the Challenges of Urban Transformation in Europe. In Public Space and the Challenges of Urban Transformation in Europe; Taylor Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Penn, A.; Hillier, B.; Banister, D.; Xu, J. Configurational Modelling of Urban Movement Networks. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1998, 25, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How to Study Public Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-61091-525-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zamanifard, H.; Alizadeh, T.; Bosman, C.; Coiacetto, E. Measuring Experiential Qualities of Urban Public Spaces: Users’ Perspective. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-61091-023-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kostof, S. The City Assembled by Kostof, Spiro, 1st ed.; Bulfinch: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8212-2599-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1st ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, P. The New Urbanism. Toward an Architecture of Community; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Resilient Urban Planning: Major Principles and Criteria. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City Planning and Population Health: A Global Challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervero, R.; Kockelman, K. Travel Demand and the 3Ds: Density, Diversity, and Design. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 1997, 2, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baobeid, A.; Koç, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Walkability and Its Relationships With Health, Sustainability, and Livability: Elements of Physical Environment and Evaluation Frameworks. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 721218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.T.; Arsenio, E.; Santos, F.C.; Henriques, R. Walkability Defined Neighborhoods for Sustainable Cities. Cities 2024, 149, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzka, J.; Burda, I.; Nyka, L. Walkability and Flood Resilience: Public Space Design in Climate—Sensitive Urban Environments. Urban Plan. 2025, 10, 9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Leary, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Hess, P.M. The Development of a Walkability Index: Application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nes, A.V. Indicating Street Vitality in Excavated Towns. Spatial Configurative Analyses Applied to Pompeii. In Spatial Analysis and Social Spaces: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Interpretation of Prehistoric and Historic Built Environments; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 277–296. ISBN 978-3-11-026643-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Cities as Movement Economies. Urban Des. Int. 1996, 1, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, L.J.; Dunsiger, S.I.; Marcus, B.H. Walk ScoreTM As a Global Estimate of Neighborhood Walkability. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Depthmap: A Program to Perform Visibility Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the Third International Space Syntax Symposium, Georgia Technological Institute, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–11 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Ban, Y. Comparative Analysis on Topological Structures of Urban Street Networks. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, S.; Crucitti, P.; Latora, V. The Network Analysis of Urban Streets: A Primal Approach. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2006, 33, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; Doxa, M.; O’Sullivan, D.; Penn, A. From Isovists to Visibility Graphs: A Methodology for the Analysis of Architectural Space. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2001, 28, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, X. How Block Density and Typology Affect Urban Vitality: An Exploratory Analysis in Shenzhen, China. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Spatial Sustainability in Cities: Organic Patterns and Sustainable Forms. Available online: http://www.sss7.org/Proceedings_list.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Donegan, L.; Silveira, J.A.R.; da Silva, G. Under and over: Location, Uses and Discontinuities in a Centrally Located Neighbourhood in João Pessoa City Reflecting Current Urban Planning Effects. Urbe Rev. Bras. De Gestão Urbana 2019, 11, e20180123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, M.; Fonseca, F.; Ramos, R. Combining Multi-Criteria and Space Syntax Analysis to Assess a Pedestrian Network: The Case of Oporto. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulaki, I. Directions in Space Syntax. Space Syntax Modelling of Pedestrian Flows for Sustainable Urban Development. In Proceedings of the 13th Space Syntax Symposium, Bergen, Norway, 20–24 June 2022; p. K02.1-19. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A. From Axial to Road-Centre Lines: A New Representation for Space Syntax and a New Model of Route Choice for Transport Network Analysis. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-5116-9776-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, N. Fractional Configurational Analysis and a Solution to the Manhattan Problem. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–11 May 2001; pp. 26.1–26.13. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, W.R.G.; Yang, T.; Turner, A. Normalising Least Angle Choice in Depthmap—And How It Opens up New Perspectives on the Global and Local Analysis of City Space. J. Space Syntax 2012, 3, 155–193. [Google Scholar]

- Foadmarashi, M.; Serdoura, F. Vitality in Time: An Approach to the Use of Urmia Bazaar. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Architecture and Urban Design, Tirana, Albania, 24–26 November 2021; Volume 1, pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-59139-7. [Google Scholar]

- EL-Khouly, T.; Penn, A. Order, structure and disorder in space syntax and linkography: Intelligibility, entropy, and complexity measures. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium, Santiago, Chile, 3–6 January 2012; pp. 8242:1–8242:22. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, K. A Configurational Approach to Analytical Urban Design: ‘Space Syntax’ Methodology. Urban Des. Int. 2012, 17, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzali, H. Urmia in Time, 1st ed.; Anzali: Urmia, Iran, 2000; ISBN 964-6614-07-8. [Google Scholar]

- Farnahad Consultanat Engineers. Revision of The Urmia Master Plan; Farnahad Consultanat Engineers: Tehran, Iran, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tose va Omran Consultant Engineers. Detailed Plan of the Urmia City; Tose va Omran Consultant Engineers: Tehran, Iran, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- FoadMarashi, M.; Serdoura, F. Public Space Use: An Approach to Livability in Urmia Bazaar, Iran. In Formal Methods in Architecture; Eloy, S., Leite Viana, D., Morais, F., Vieira Vaz, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, S.M. De La Cite de La Ville: A Historical Analysis of The Concept of The City and Its Physical Appearance, 1st ed.; University of Tehran Press: Tehran, Iran, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanzadeh, H. A Brief History of the City and Urbanization in Iran (Ancient Era to 1976), 1st ed.; Chahar Tagh: Tehran, Iran, 2011; ISBN 978-964-95426-6-9. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Level | Case Study Urmia Bazaar Block | |||||

| NAC | NAC r2 | Connectivity | Entropy | NAI | NAI r2 | ||

| 1933 | Max | 1.341439 | 1.244948 | 13 | 4.05235 | 0.000615 | 0.259384 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.443708 | 0.00034 | 0.024715 | |

| Average | 0.708044 | 0.472593 | 3.623188406 | 3.760397 | 0.000473 | 0.086219 | |

| 1948 | Max | 1.583007 | 1.349069 | 46 | 3.551014 | 0.001002 | 0.259384 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.938095 | 0.000371 | 0.008861 | |

| Average | 0.702157 | 0.458066 | 4.087452471 | 3.165736 | 0.000644 | 0.078621 | |

| 2023 | Max | 1.618063 | 1.332413 | 85 | 2.853 | 0.000292 | 0.15904 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5829 | 0.000125 | 0.000625 | |

| Average | 0.651307 | 0.416924 | 4.575596817 | 2.707674 | 0.000194 | 0.036586 | |

| Inner City of Urmia | |||||||

| NAC | NAC r2 | Connectivity | Entropy | NAI | NAI r2 | ||

| 1933 | Max | 1.341439 | 1.290537 | 13 | 4.071741 | 0.000615 | 0.259384 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.443708 | 0.000298 | 0.024468 | |

| Average | 0.614342 | 0.413012 | 3.044740024 | 3.840315 | 0.000453 | 0.100452 | |

| 1948 | Max | 1.583007 | 1.349069 | 46 | 3.554616 | 0.001002 | 0.259384 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.911469 | 0.000331 | 0.008861 | |

| Average | 0.620543 | 0.403187 | 3.189156627 | 3.185177 | 0.00062 | 0.095075 | |

| 2023 | Max | 1.618063 | 1.332413 | 85 | 3.048458 | 0.000292 | 0.259384 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5829 | 0.000105 | 0.00378 | |

| Average | 0.568486 | 0.363084 | 3.542609854 | 2.761937 | 0.000181 | 0.097031 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foadmarashi, M.; Eskandari, F.; Serdoura, F. Walking and Time! The Style of Walkability in Urmia Old Town. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310758

Foadmarashi M, Eskandari F, Serdoura F. Walking and Time! The Style of Walkability in Urmia Old Town. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310758

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoadmarashi, Momen, Farnaz Eskandari, and Francisco Serdoura. 2025. "Walking and Time! The Style of Walkability in Urmia Old Town" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310758

APA StyleFoadmarashi, M., Eskandari, F., & Serdoura, F. (2025). Walking and Time! The Style of Walkability in Urmia Old Town. Sustainability, 17(23), 10758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310758