1. Introduction

The rapid increase in global energy consumption and the intensifying effects of climate change have made energy efficiency in buildings more critical than ever [

1]. Buildings account for approximately 40% of total global energy consumption, a proportion that rises even higher in developed countries [

2]. Heating, cooling, and lighting systems are the primary sources of energy demand. Growing populations, higher living standards, and technological advancements continue to drive energy consumption in buildings upward, which in turn leads to significant carbon emissions and greenhouse gas output. Enhancing energy efficiency has therefore become a vital necessity for achieving Net-Zero Energy Building (NZEB) targets [

3] and ensuring a sustainable future. Consequently, accurately predicting building energy consumption is a key factor in sustainable energy management and smart city applications. Achieving these goals requires supporting operational processes with digital twin models of buildings [

4].

However, the complex and nonlinear relationships among the numerous factors affecting a building’s energy performance—such as weather conditions, geometry, material properties, occupancy patterns, and indoor temperatures—make it difficult for conventional statistical or physics-based models to deliver accurate predictions [

5,

6]. The high dimensionality and noise in operational data further increase the risk of prediction errors.

To overcome these challenges and achieve high-accuracy predictions, machine-learning (ML) techniques have emerged in recent years as the primary tools for building energy consumption forecasts due to their ability to learn meaningful relationships from large datasets [

7]. The success of ML algorithms directly depends on the quality of the selected input features. Irrelevant or redundant features not only decrease predictive performance but also unnecessarily increase computation time and model complexity [

8]. Therefore, identifying the optimal subset of features is the first step toward developing high-performing, efficient models.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of ML models depends mainly on the quality of the chosen features. Irrelevant or redundant features extend training time and reduce both accuracy and interpretability [

8]. Hence, feature-selection studies using biologically or nature-inspired algorithms have become prominent in the literature. Most existing works, however, evaluate developed models only in terms of accuracy metrics (Mean Absolute Error—MAE, Root Mean Squared Error—RMSE, Coefficient of Determination—R

2) and overlook other criteria that are critical for real-time operational applications—such as computational cost, training duration, model complexity, and prediction time. A limited number of studies, such as [

9], have emphasized the importance of evaluating complexity, cost, and performance together for real-world success.

In recent years, ML and deep learning (DL) techniques have been widely used for modeling and forecasting building energy consumption [

10]. Earlier statistical approaches were limited in their ability to capture nonlinear interactions [

11]. In contrast, ML and DL algorithms can effectively model such complex relationships, providing significantly higher predictive accuracy. In particular, gradient boosting algorithms—such as XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM—have shown strong performance in energy prediction tasks [

10]. Yet, for successful deployment in real-world building management systems and smart grids, computational efficiency, speed, and model simplicity are as vital as accuracy. Therefore, there is a growing need in the literature for comprehensive, multi-criteria evaluation frameworks that assess models not only in terms of accuracy but also in terms of their practical viability [

9].

Numerous approaches have been developed in the literature, utilizing different datasets. The UCI Energy Efficiency dataset [

12] has emerged as a benchmark frequently used in studies of building energy consumption prediction. Ghasemkhani et al. [

13] combined a Tri-Layered Neural Network (TNN) with the Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (MRMR) method to improve feature selection and prediction performance, achieving high accuracy. Similarly, Al-Essa et al. [

14] addressed collinearity and parameter uncertainty by applying Bayesian regression models. Their study, which used this dataset to mitigate multicollinearity, demonstrated enhanced model stability. However, these studies generally did not evaluate key practical aspects such as training time, prediction time, feature efficiency, or suitability for real-world applications. Furthermore, the hybrid use of nature-inspired feature-selection algorithms with machine-learning models has been only limitedly explored on this dataset.

Although hybrid metaheuristic models have been explored in general optimization and high-dimensional feature-selection problems, their application in building energy prediction remains limited. For instance, Aly and Alotaibi [

15] proposed a Hybrid Butterfly–Grey Wolf Optimization (HB-GWO) algorithm and demonstrated its effectiveness in feature-selection tasks. However, despite such advances, no existing study has applied a BOA–GWO hybrid model specifically for estimating building energy loads. The present study explicitly addresses this gap by implementing and evaluating the BOA–GWO framework within a multi-criteria assessment context for predicting heating and cooling loads.

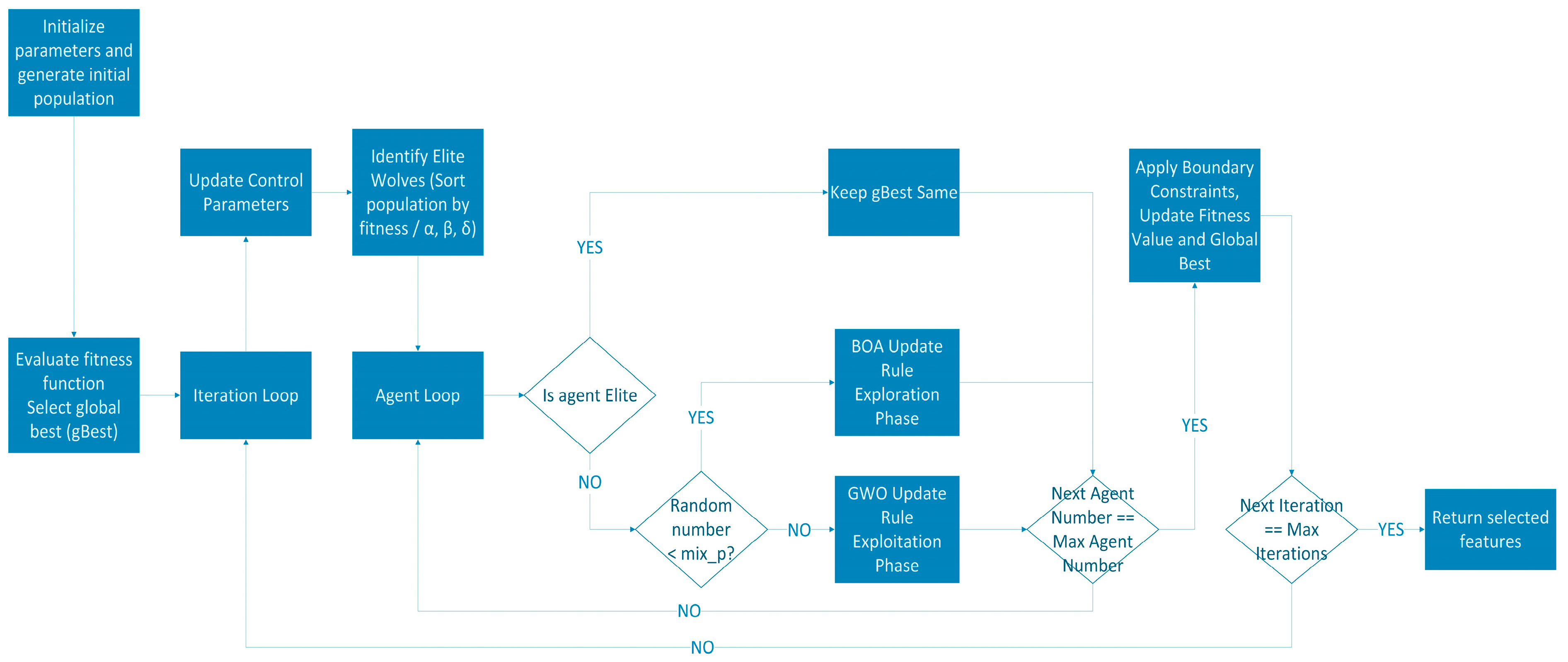

The primary aim of this study is to introduce a multi-criteria evaluation framework that considers both accuracy-related metrics and computational performance factors, such as training and prediction time, for predicting building energy consumption. Two nature-inspired algorithms—the Butterfly Optimization Algorithm (BOA) and the Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm (GWO)—were first applied separately for feature selection, and then combined into a new hybrid model (BOA–GWO) to leverage their complementary strengths. The proposed approach seeks to achieve both high predictive accuracy and computational efficiency.

In this study, machine learning is employed not only as an alternative prediction method but as a core mechanism to reveal complex nonlinear interactions among architectural, geometric, and thermal building features. Unlike traditional statistical approaches, ML models can automatically learn hierarchical feature relationships without predefined functional assumptions. In this context, ML serves as the computational backbone of an efficient and scalable energy load prediction framework suitable for smart building applications and resource-constrained environments.

This study seeks to integrate ML methods with nature-inspired feature-selection algorithms for predicting building energy consumption. Using the UCI Energy Efficiency dataset, the performance of different ML algorithms was compared, and nature-inspired methods (BOA and GWO) were integrated to form a hybrid model. Furthermore, not only prediction accuracy but also training and prediction times were evaluated, offering a comprehensive analysis.

The contribution of this study lies in conducting a multi-criteria evaluation of the widely used UCI Energy Efficiency dataset, going beyond the accuracy-focused analyses in the existing literature. Additionally, the use of BOA, GWO, and the proposed hybrid BOA–GWO feature-selection algorithms, combined with modern ML methods such as CatBoost and XGBoost, fills an identified research gap and presents a novel approach applicable both academically and practically.

Moreover, unlike studies primarily focused on building physics or energy performance assessment, this work emphasizes the methodological contributions from a machine learning perspective. Specifically, the study highlights how hybrid feature-selection mechanisms (BOA–GWO) improve model performance, training efficiency, and feature compactness, rather than developing new physical or algorithmic models. In fact, this research does not introduce a new physical energy model or an entirely novel optimization algorithm. Instead, it develops and implements a customized hybrid BOA–GWO framework, evaluating its integration with modern ML techniques to enhance both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency in building energy load estimation. Thus, the research advances the field of data-driven energy prediction by demonstrating the added value of hybrid metaheuristic-supported ML pipelines for practical, real-time applications, laying the foundation for scalable deployment in intelligent energy management systems.

This study addresses this critical gap by aiming not only to achieve the highest level of predictive accuracy but also to select the most efficient and practically applicable model within a multi-criteria evaluation framework. As emphasized by pioneering studies such as [

9], such a comprehensive assessment provides the construction industry with not only accurate but also practical and fast decision-support systems, thereby offering a unique and valuable contribution to the field.

The proposed method offers significant advantages not only in theoretical accuracy and performance but also in practical usability. The developed framework is scalable for implementation in smart buildings, energy management, and IoT-based applications. Thus, the study aims to bridge the gap between scientific research and real-world applications in sustainable energy management.

In addition to improving prediction accuracy, this study employs a multi-criteria evaluation approach that also considers training time, prediction time, and the number of selected features as key performance measures. These metrics are critical for real-time, embedded smart building platforms, where hardware limitations and low-latency decision-making requirements make computational efficiency essential. By integrating metaheuristic-based feature selection with modern machine-learning models, the proposed framework emphasizes the importance of achieving a balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. This approach ensures that the developed models are not only theoretically effective but also practically deployable in intelligent building energy management systems, enabling scalable, resource-efficient implementations in real-world settings.

The following sections are organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review,

Section 3 describes the materials and methods,

Section 4 discusses the results, and

Section 5 concludes with the main findings and directions for future work.

4. Results

In this study, three different feature-selection models were developed, and regression prediction models were constructed for the target variables using the parameters obtained from these selectors. Experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 4800H CPU, 16 GB DDR4 RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3050 GPU.

All models were implemented in Python 3.10 using PyCharm 2022.2.1 and the scikit-learn, TensorFlow, NumPy, and pandas libraries. The dataset was partitioned into 80% training data and 20% testing data, and fixed random seeds were applied for the data split, metaheuristic executions, and model training to ensure experimental reproducibility. Feature selection was performed once per metaheuristic algorithm, after which ML models were trained using the selected feature subsets. Default scikit-learn parameters were used to ensure a fair baseline comparison, focusing on the impact of feature-selection strategies rather than hyperparameter tuning. Training and inference times were recorded in microseconds using the time.perf_counter() function. Due to high-precision timing, runtime values smaller than 0.0009 s are displayed as 0.000 in the tables for clarity and accuracy.

First, the features selected for the variables Y

1 (heating load) and Y

2 (cooling load) by each feature selector were compared. Subsequently, the performance of the prediction models built with these feature subsets was evaluated using the MAE, RMSE, and R

2 metrics. Additionally, the fit time and prediction time values were examined to assess the models’ time-performance efficiency. Detailed information on the parameters of the three feature selectors used in the study is presented in

Table 4.

The GWO algorithm typically has a minimal number of user-defined parameters. Therefore, compared with BOA, only a small amount of parameter tuning was required. It indicates that the algorithm has a simpler, more computationally lightweight structure.

In contrast, the BOA and hybrid BOA–GWO algorithms have more adjustable parameters than the GWO algorithm. In addition to the number of iterations and population size, these algorithms include parameters such as the c coefficient, probability (p), threshold value (thres), and the α and β coefficients. These additional parameters control the exploration–exploitation balance of BOA, which models the butterflies’ scent perception and movement behaviors, and they directly influence the search performance of the algorithm.

Table 5 and

Table 6 summarize the features identified by each of the three feature selectors as the most influential for predicting Y

1 (heating load) and Y

2 (cooling load), respectively.

The purpose of applying the three different feature selectors in this study was to identify which attributes were more influential for both Y1 and Y2 parameters.

As shown in

Table 5, all three feature-selection algorithms identified the same set of features influencing the Y

1 parameter, indicating strong consistency across the applied methods. Each of them selected five out of the eight available features. The unselected features were “Wall Area,” “Orientation,” and “Glazing Area Distribution.” The fact that all three models selected the same set of features demonstrates consistency and emphasizes that the three unselected variables were not as influential as the others. Since the selector execution times were very close and relatively short, all three algorithms can be considered practically applicable in terms of performance. Also,

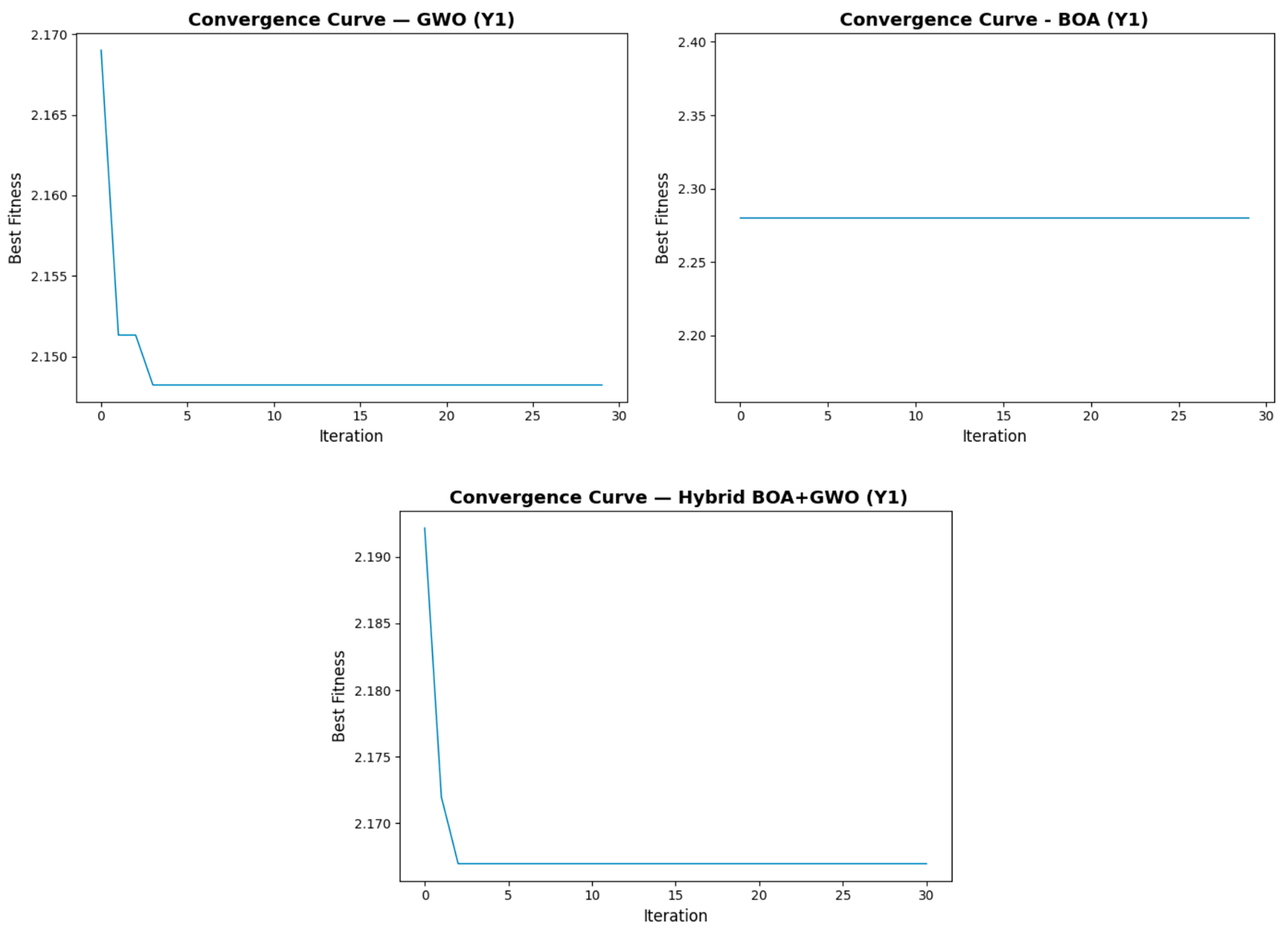

Figure 3 shows the convergence behavior of the feature selectors for feature Y

1. GWO demonstrated compelling exploration of the search space, achieving a better solution in the initial iterations. BOA, in contrast to GWO, produced a constant value across all iterations. The resulting hybrid model, similar to the GWO model, achieved successful results in the initial iterations but found the best solution with a clearer progression.

As shown in

Table 6, the selection of features influencing the Y

2 parameter differed among the three feature-selection models. The standard variables selected by all models were “Relative Compactness,” “Overall Height,” and “Glazing Area.” It indicates that these three attributes are the most influential features for the Y

2 parameter. The most notable observation is that the BOA model selected all features, implying that, apart from the three standard variables, the contribution of the remaining attributes may vary depending on the model. While the complete agreement among models for Y

1 provides confidence in their consistency, the variation in selected features for Y

2 suggests that the Y

2 parameter exhibits a more complex and multivariate structure.

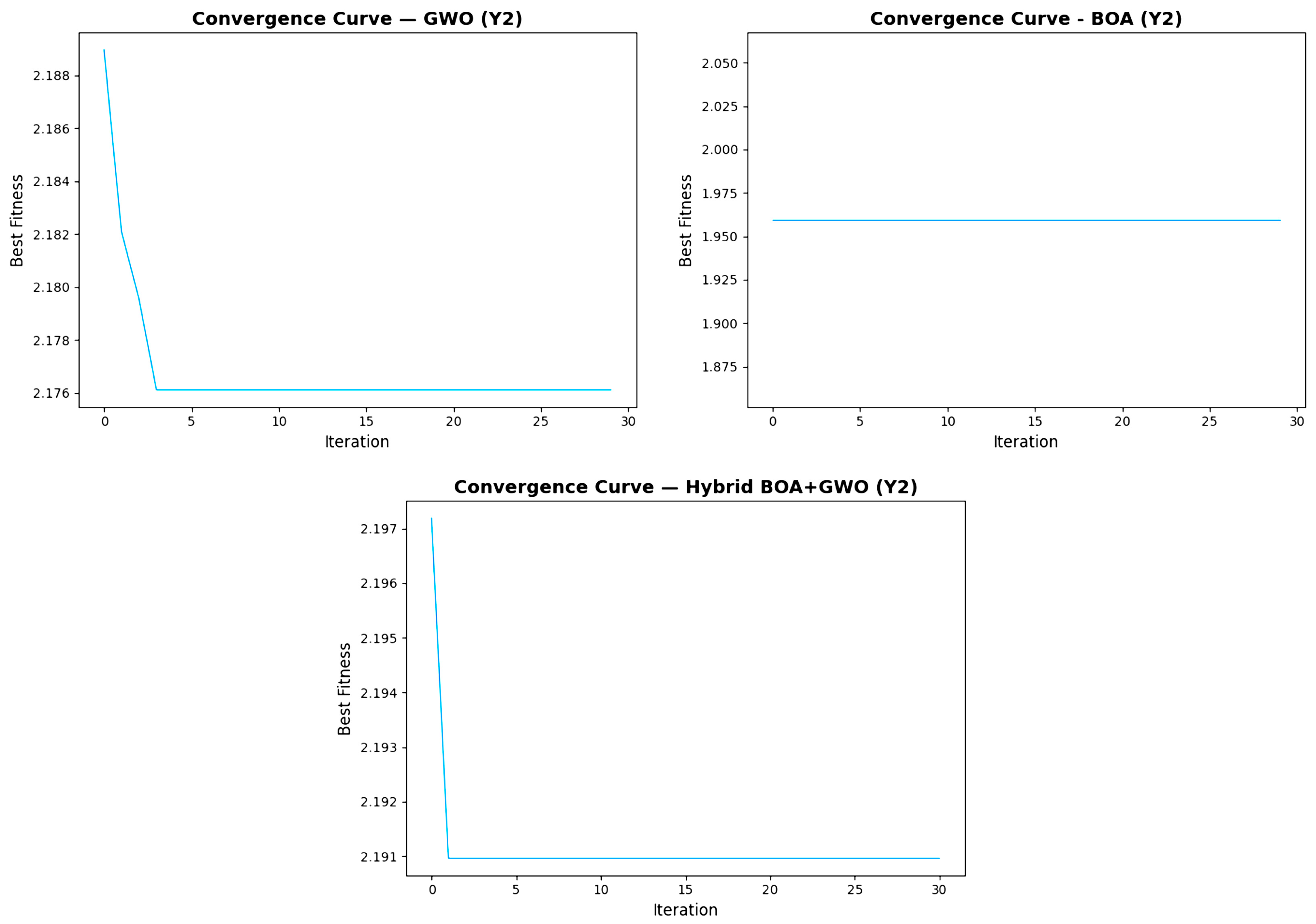

Figure 4 shows the convergence behavior of the feature selectors for feature Y

2. The BOA model exhibits the same behavior for both Y

1 and Y

2. GWO and the hybrid BOA-GWO models progress more smoothly than Y

1. Unlike Y

1, the hybrid model reaches the best solution earlier in Y

2 than the GWO model.

In the study, eight different machine-learning algorithms were also used to construct prediction models. These models were evaluated using three performance metrics: MAE, RMSE, and R2. The Y1 and Y2 variables were predicted separately, and for each feature subset determined by the three selectors, independent prediction models were developed. To avoid confusion in the results obtained using the evaluation metrics in the study, the four digits after the comma were retained.

After feature selection using the GWO algorithm, all tree-based models achieved nearly identical and excellent R

2 values for the Y

1 variable. However, as shown in

Table 7, LightGBM produced the best overall results, while the linear models performed relatively poorly. Additionally, the fit time of XGBoost was observed to be the longest among all models, indicating a higher computational demand during training.

Predictions for both Y1 and Y2 were made separately using the features selected by the GWO feature selector. The GWO model utilized five features for Y1 and four features for Y2.

As shown in

Table 8, the LightGBM model achieved the best performance, with an R

2 value of 0.9639 and a MAPE value of 4.1746. The CatBoost and other tree-based models also produced similarly high and consistent results. In contrast, the linear models (LR and SVR) performed poorly, with R

2 values below 0.90, indicating a weaker predictive capability compared to the other models. When fit and prediction times are also considered, LightGBM stands out as the model that is both the fastest and the most accurate in predicting energy consumption.

As shown in

Table 9, the results are highly consistent with those presented in

Table 7, as both feature selectors (GWO and BOA) selected the same set of features for the Y

1 parameter. However, when the results for Y

2 are analyzed (

Table 10), some differences can be observed. In the BOA-based feature-selection process, seven features were selected. Similar to the GWO results, the LightGBM model achieved the best overall performance with an R

2 value of 0.9631. When the MAPE values obtained in the Y

1 and Y

2 estimates after applying the BOA feature selector are examined, it is observed that they yield results in parallel with the other error metrics, and LightGBM has the lowest MAPE value. The MAE and RMSE values of the LightGBM model were also lower than those of the other models. In terms of computation, the fit and predict times again showed that LightGBM was the fastest, whereas CatBoost required a longer training duration.

As shown in

Table 11, the model results are identical to those obtained with the other two feature selectors, demonstrating consistent performance for the Y

1 parameter across all selection methods. However, upon analyzing

Table 12, differences become apparent. For Y

2, predictions were made using the three features selected by the hybrid BOA–GWO algorithm. In this case, the best performance was achieved with the CatBoost model, unlike the other feature selectors, where LightGBM had previously shown the best results. While the DT, ET, XGBoost, and RF models produced almost identical levels of accuracy, LightGBM exhibited a slightly higher MAE value. Regarding computation times, Decision Tree, Extra Trees, and XGBoost demonstrated very fast fit durations, confirming their efficiency in training.

Table 13 and

Table 14 present the results obtained without applying feature selection, i.e., when all features were used in model training. When

Table 13 is examined for the Y

1 parameter, it can be observed that the CatBoost model achieved the lowest error values, with MAE = 0.2398, RMSE = 0.3352, R

2 = 0.9989, and MAPE = 1.0946. Both XGBoost and LightGBM also demonstrated performances very close to CatBoost, confirming the strong predictive power of gradient boosting methods. The linear models (LR and SVR), on the other hand, once again underperformed compared to tree-based algorithms, indicating their limited ability to model nonlinear relationships within the dataset.

As shown in

Table 14, the best performance for the Y

2 parameter was again achieved with the CatBoost model, with MAE = 0.4437, RMSE = 0.6746, R

2 = 0.9950, and MAPE = 1.6944. Although XGBoost achieved a similarly high R

2 value, DT, RF, and ET models showed higher error rates, indicating slightly weaker predictive performance. Once again, the LR and SVR models demonstrated poor results, confirming that linear algorithms are not suitable for accurately capturing the nonlinear relationships in the building energy consumption data.

The gradient boosting–based tree models achieved the lowest errors and highest R2 values for both Y1 and Y2 predictions in all cases. In particular, the CatBoost model consistently delivered the best or nearly best performance across all tables. In contrast, the linear models showed weak performance without feature selection, although their predictive accuracy improved slightly when feature selection was applied.

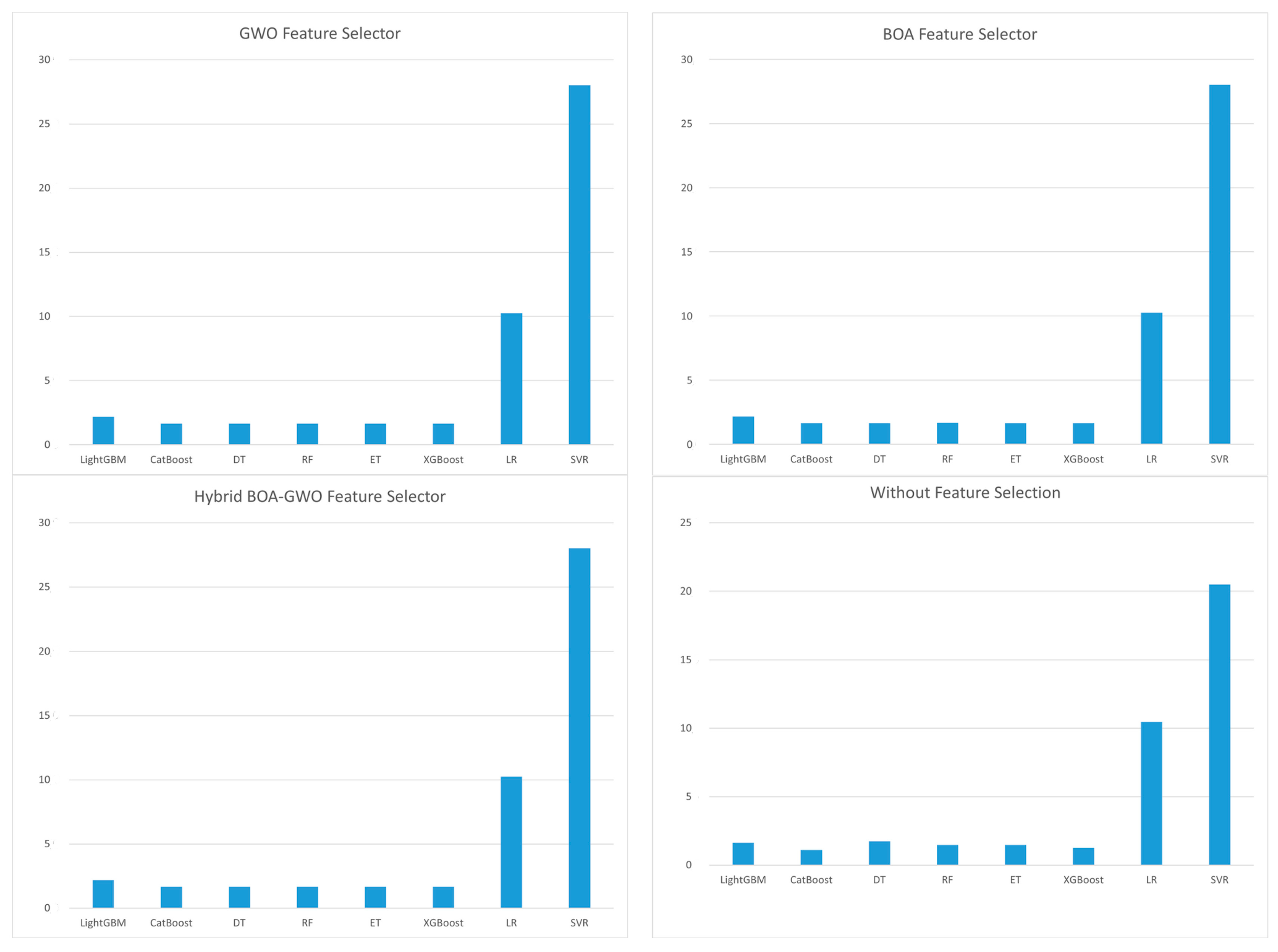

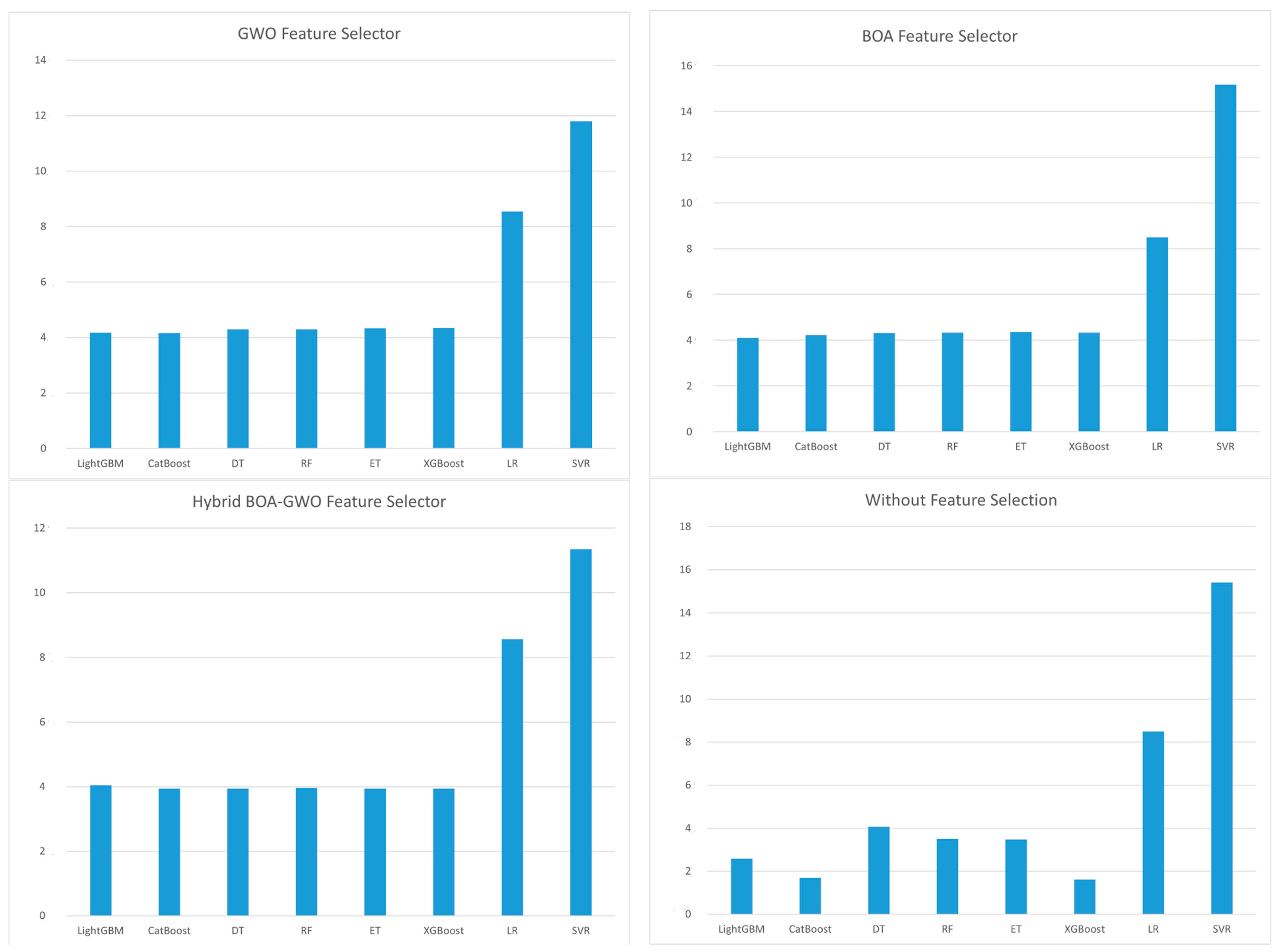

MAPE’s normalization of errors as a percentage enables a more objective interpretation by presenting the prediction accuracy of models with different structures from a unified perspective. Therefore, for unbiased comparison of models,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 display histograms showing the MAPE values obtained by the models in each scenario. An examination of the figures reveals that gradient descent-based models achieve the lowest MAPE values for both Y

1 and Y

2. In contrast, linear models exhibit poorer performance. Moreover, the statistics illustrate that tree-based ensemble methods yield more reliable and stable predictions, while feature selection further enhances model performance without compromising computational efficiency.

Applying feature selection to Y1 and Y2 resulted in different numbers of selected features: five were consistently chosen for Y1, while the subset for Y2 varied depending on the feature-selection algorithm. In several models, especially for Y2, slight improvements in prediction accuracy were observed, indicating that the selected features were indeed informative and relevant to the target variables.

While the BOA tended to select a larger number of features and GWO focused on a smaller subset, the hybrid BOA–GWO algorithm balanced exploration and exploitation, producing a more compact yet highly predictive feature subset. This balance reduced model complexity without sacrificing accuracy, particularly for the cooling load (Y2) variable; with the hybrid approach, the R2 value increased from 0.9631 (BOA) and 0.9639 (GWO) to 0.9670.

In terms of the performance–time trade-off, LightGBM achieved the fastest training times with strong performance, while CatBoost provided the highest accuracy, albeit with slightly longer training durations. The classical linear models produced results quickly but had significantly lower accuracy.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with those reported by Bassi et al. [

10], who demonstrated that gradient boosting models such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost outperform classical regression techniques for building energy prediction. Similarly, Afzal et al. [

17] showed that hybrid models integrating neural networks with optimization algorithms yield higher accuracy compared to standalone models. Aligned with these studies, the results of the present research confirm the superior performance of gradient boosting methods, with CatBoost achieving the highest accuracy (mostly R

2 > 0.99).

However, unlike previous studies that primarily focused on accuracy metrics [

16,

19], this research extends the analysis by incorporating training time, prediction time, and feature efficiency into a multi-criteria evaluation. This comprehensive assessment reveals that while CatBoost provides the highest predictive accuracy, LightGBM achieves comparable accuracy with faster training, and the proposed hybrid BOA–GWO feature selector enhances efficiency without compromising performance.

In addition to improving predictive performance, feature selection also enhances model interpretability by highlighting the parameters that influence building energy consumption. In building energy management, understanding which physical characteristics, such as overall height, relative compactness, or glazing area, influence heating and cooling loads allows facilities management to make more informed decisions about design and control strategies.

These outcomes confirm that integrating metaheuristic optimization with machine learning provides a robust, accurate, and efficient method for predicting energy consumption, supporting both academic and practical advancements in sustainable building management.

5.1. Comparison with Existing Smart Building Energy Management Approaches

Previous research in smart energy management has predominantly relied on deep learning or reinforcement learning–based models for load forecasting and energy optimization in IoT-enabled buildings. While these approaches can achieve high predictive accuracy, they typically require substantial computational resources, frequent retraining, and access to large-scale real-world datasets. The proposed BOA–GWO–supported gradient boosting framework prioritizes computational efficiency and compact feature selection, making it ideal for embedded smart building environments. It complements existing deep-learning-based solutions by providing a lightweight and efficient alternative for real-time energy prediction under resource constraints.

This emphasis on computational efficiency is consistent with findings in recent smart building studies, which highlight that deep-learning-based approaches, while accurate, often require substantial processing power and frequent retraining, making lightweight ML-based solutions more suitable for embedded and IoT environments [

35,

36].

5.2. Dataset Limitations and Generalizability

This study utilized the UCI Energy Efficiency dataset [

12], which consists of 768 simulated residential building samples defined by eight input features and two continuous target variables (heating and cooling loads). Although this dataset is widely used as a benchmark in the literature, it contains inherent limitations that may introduce bias in model generalization. Specifically, it represents only simulated residential buildings with fixed geometric and thermal parameter ranges and balanced heating/cooling load distributions, which do not fully reflect the diversity of real-world building stock, including commercial and mixed-use facilities, varying climate zones, and heterogeneous occupancy and operational conditions. Such restricted variability may lead to optimistic performance within this benchmark setting and insufficient representation of extreme or irregular behaviors observed in actual building energy systems. Therefore, the promising predictive accuracy and computational efficiency achieved by the proposed hybrid BOA–GWO framework should be interpreted as preliminary rather than definitive evidence of real-world generalizability.

Furthermore, the dataset consists of static building attributes rather than time-series energy consumption data. As a result, the proposed model predicts energy loads for buildings with similar architectural and thermal characteristics rather than forecasting future energy consumption trajectories. It enables controlled performance evaluation but does not account for temporal dynamics, operational variability, or adaptive behavior in real-time systems.

Future work will therefore focus on applying the hybrid BOA–GWO approach to real-time building datasets and time-series energy consumption models. It will enable the assessment of its performance across diverse climates, building typologies, operational scenarios, and dataset scales, as well as the evaluation of its short- and long-term forecasting capability, adaptive learning performance, and suitability for real-time smart building and IoT-enabled applications.

For clarity, dataset-related limitations are summarized in

Table 15.

6. Conclusions

This study successfully proposes a hybrid approach that integrates nature-inspired feature selection algorithms (GWO, BOA, and Hybrid BOA–GWO) with robust gradient boosting machine-learning methods (LightGBM, CatBoost, and XGBoost) to improve the predictive performance of building heating (Y1) and cooling (Y2) loads using the UCI Energy Efficiency dataset. Unlike studies that focus solely on optimizing ML models, the primary contribution here is improving predictive performance through a hybrid feature-selection strategy. Secondary considerations included training time and feature compactness to assess real-world applicability.

The key findings demonstrate that integrating nature-inspired feature-selection algorithms with machine-learning methods improves both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. Comparisons of model fit and prediction times further revealed that hybrid approaches achieved higher accuracy in shorter time than classical methods. For the heating load (Y1), all models consistently selected the same features, indicating their strong influence on prediction. In contrast, the variability in the features chosen for the cooling load (Y2) suggests a more complex, multivariate structure. Overall, combining nature-inspired feature selection with gradient-boosting models provides a computationally efficient, highly accurate, and straightforward approach for predicting building energy loads. It demonstrates that accuracy, computational speed, and model simplicity can be jointly optimized for real-time and resource-constrained smart-building applications.

The proposed hybrid BOA–GWO feature selection algorithm leverages the global exploration capability of BOA and the local exploitation ability of GWO, producing a balanced, compact, and highly predictive feature set. When combined with XGBoost, it achieved the best performance for Y2 prediction (R2 ≈ 0.967) using only three features, demonstrating high predictive accuracy with reduced computational cost and model complexity. In addition to the accuracy improvements achieved with gradient boosting methods, the hybrid approach outperformed the individual BOA and GWO implementations. It provides efficiency and stability, making it especially suitable for real-time, resource-constrained applications such as IoT-based energy management and smart building systems.

To the best of our knowledge, while hybrid BOA–GWO schemes have been explored in other computational intelligence domains, this study represents one of the first applications of a BOA–GWO–based feature-selection framework specifically for building energy consumption prediction. Rather than introducing a new metaheuristic, it adapts the BOA–GWO hybrid logic to the building energy domain and evaluates performance from a multi-criteria perspective, including accuracy, training time, and feature compactness. This domain-oriented adaptation and comprehensive evaluation offer practical value for real-time and resource-constrained smart building environments.

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. The UCI Energy Efficiency dataset, although widely used in the literature, does not fully reflect the diversity and scale of real-world building energy data. It includes only simulated residential buildings with fixed geometric and thermal parameter ranges and balanced heating/cooling loads, which may not reflect mixed-use or commercial buildings, different climatic zones, or dynamic operational conditions. Additionally, the dataset contains static building features rather than time-dependent consumption patterns; therefore, the model predicts energy loads for buildings with similar characteristics, rather than forecasting temporal energy demand. Thus, the results and conclusions drawn from this single dataset should be interpreted with caution and cannot be directly generalized to broader real-world scenarios or large-scale IoT-based applications. Furthermore, because the research is based on a single benchmark dataset, it may not accurately reflect the diversity of actual building energy usage across various climates and building categories.

Additionally, since the primary focus of this research was to evaluate the effectiveness of hybrid feature-selection strategies rather than hyperparameter optimization, all ML models were trained with default parameter configurations. Future work should validate the hybrid BOA–GWO framework on larger and more diverse datasets, including commercial and industrial buildings across various climatic conditions and dynamic operational profiles. Integrating additional nature-inspired algorithms or deep-learning-based hybrid approaches, as well as conducting systematic hyperparameter tuning, could further improve performance and generalizability. Moreover, although the proposed nature-based feature selectors have demonstrated strong predictive performance, future studies may compare them with classical baselines such as Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), and tree-based feature-importance metrics. Reporting the mean and standard deviation of evaluation metrics across multiple runs with different random seeds on more comprehensive benchmark datasets would also strengthen the robustness and reproducibility of the results. Finally, applying the model to time-series and real-time energy data streams will enable the assessment of its short- and long-term forecasting capabilities, adaptive learning potential, and suitability for IoT-enabled smart grid environments.