Digital Economy’s Impact on Tourism Eco-Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Eco-Efficiency

2.2. Digital Economy

2.3. The Impact of the Digital Economy on Tourism Eco-Efficiency

2.4. Eco-Efficiency Measurement Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. The Models

3.1.1. The Super-SBM–Undesirable Model for Tourism Eco-Efficiency Assessment

3.1.2. Panel Model

3.2. Explanations of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variable and Moderating Variable

3.3. Data Selection

4. Results

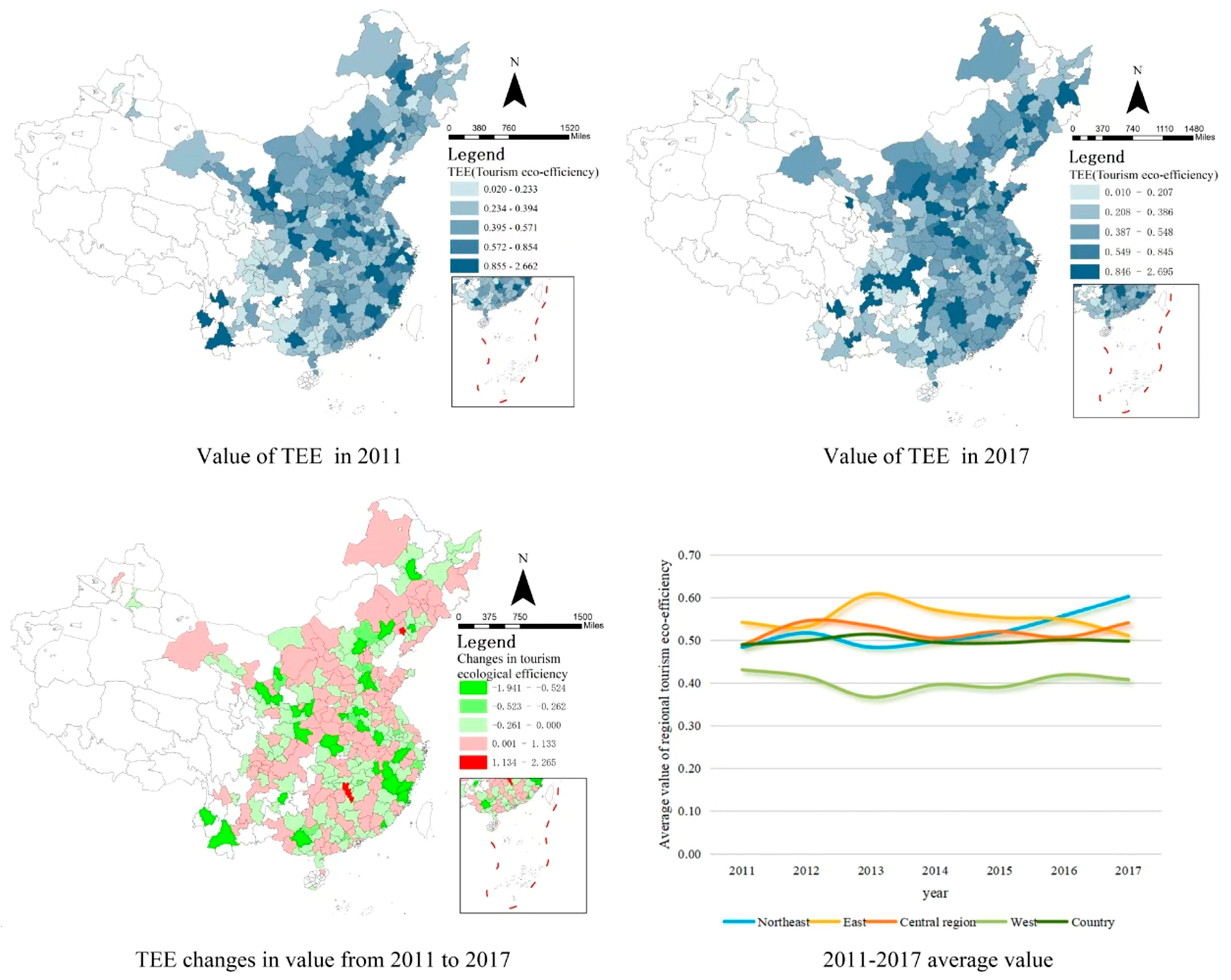

4.1. Results of National TEE Evaluation

4.2. Regional Heterogeneity of TEE in China

4.3. Results of Panel Model

4.3.1. Panel Regression Results

4.3.2. Regional Differences

4.3.3. The Moderating Effect of the Digital Economy on TEE

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Evolutionary Characteristics of Tourism Eco-Efficiency

5.1.2. The Inhibitory Effect of the Digital Economy on Tourism Eco-Efficiency

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ouyang, R.; Jing, W.; Liu, Z.; Tang, A. Development of China’s digital economy: Path, advantages and problems. J. Internet Digit. Econ. 2024, 4, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, R.; Guo, P.; Guo, Y.; Hao, Y. The role of the digital economy in tourism: Mechanism, causality and geospatial spillover. Empir. Econ. 2023, 66, 2355–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, T.; Su, X. Application of Big Data Technology in the Impact of Tourism E-Commerce on Tourism Planning. Complexity 2021, 2021, 9925260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring Consumer Behavior in Virtual Reality Tourism Using an Extended Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Piscarac, D.; Yoo, S.-C. Meet the Virtual Jeju Dol Harubang—The Mixed VR/AR Application for Cultural Immersion in Korea’s Main Heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Huang, C. The Impact of Digital Economy Development on Improving the Ecological Environment—An Empirical Analysis Based on Data from 30 Provinces in China from 2012 to 2021. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Lu, B.; Tian, T. Spatial Correlation Network and Regional Differences for the Development of Digital Economy in China. Entropy 2021, 23, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, X.; Yu, Q.; Leng, M. How Does the Digital Economy Affect Carbon Emissions? Evidence from Panel Smooth Transition Regression Model. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Information communication technology and electricity consumption in emerging economies. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.; Alam, K. Internet usage, electricity consumption and economic growth in Australia: A time series evidence. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 862–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Fang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, F. Tourism Eco-Efficiency Measurement, Characteristics, and Its Influence Factors in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Chao, L.; Khan, T.U.; Sai, W.L.; Yazhuo, Z.; Khan, I.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Hu, Y. Insights into climate change dynamics: A tourism climate index-based evaluation of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Ceron, J.-P.; Dubois, G.; Patterson, T.; Richardson, R.B. The eco-efficiency of tourism. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 54, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Bai, B.; Qiao, Q.; Kang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J. Study on eco-efficiency of industrial parks in China based on data envelopment analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 192, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanandeh, A.E. Quantifying the carbon footprint of religious tourism: The case of Hajj. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kytzia, S.; Walz, A.; Wegmann, M. How can tourism use land more efficiently? A model-based approach to land-use efficiency for tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, C.; Alberto, F.J.; Cardoso, M.A. The impacts of the tourism sector on the eco-efficiency of the Latin American and Caribbean countries. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 78, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhong, Y. Spatial-Temporal Differences and Influencing Factors of Tourism Eco-Efficiency in China’s Three Major Urban Agglomerations Based on the Super-EBM Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Iqbal, W.; Shaikh, G.M.; Iqbal, N.; Solangi, Y.A.; Fatima, A. Measuring Energy Efficiency and Environmental Performance: A Case of South Asia. Processes 2019, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Tang, G.; Yan, B.; Xiao, X.; Han, Y. Eco-efficiency and its determinants at a tourism destination: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 60, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, X. The Spatiotemporal Relationship between Tourism Eco-Efficiency and Economic Resilience from Coupling Perspectives in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Spatial-temporal evolution and influencing factors of tourism eco-efficiency in China’s Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1067835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, G. Analysis on the Spatial-Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Spatial Network Structure of Tourism Eco-Efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, C.K.; Stiakakis, E.; Ravindran, A.R. Editorial for the special issue: Digital Economy and E-commerce Technology. Oper. Res. 2013, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, D.; Serban, E. The Digital Divide in Romania—A Statistical Analysis. Econ. Ser. Manag. 2012, 15, 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Asni, A.E.; Muk, B.; Dumancic, K. Defining and measuring the digital economy in Croatia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Economics of Decoupling (ICED), Zagreb, Croatia, 2–3 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, H.D. Understanding the Digital Economy: Challenges for New Business Models. 2000. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2566095 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, H.; Ajaz, T. Influence of renewable energy infrastructure, Chinese outward FDI, and technical efficiency on ecological sustainability in belt and road node economies. Renew. Energy 2023, 205, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lin, B. The impact of digital economy on energy rebound effect in China: A stochastic energy demand frontier approach. Energy Policy 2025, 196, 114418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Q. Digital economy, environmental regulation and green eco-efficiency—Empirical evidence from 285 cities in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1113293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, X. Does the Digital Economy Contribute to Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China’s 278 Cities. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 7250–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth-Krebs, K.; Rampen, C.; Rogers, E.; Dudley, L.; Wishart, L.J. Circular Economy Infrastructure: Why we need track and trace for reusable packaging. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 29, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Piprani, A.Z.; Yu, Z. Digital technology and circular economy practices: Future of supply chains. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partin, K.; Watchravesringkan, K. Determinants of Online Collaborative Consumption Behavior: The Application of the Theory of Reasoned Action in the Context of Apparel; Iowa State University Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Warmington-Lundstrom, J.; Laurenti, R. Reviewing circular economy rebound effects:The case of online peer-to-peer boat sharing. Resour. Conserbation Recycl. X 2020, 5, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Ni, P. The Impact of the Digital Economy on CO2 Emissions: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Al-Mulali, U.; Saboori, B. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: The role of tourism and ecological footprint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z. Tourism eco-efficiency of Chinese coastal cities—Analysis based on the DEA-Tobit model. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhan, Y.; Yin, R.; Yuan, X. The Tourism Eco-Efficiency Measurement and Its Influencing Factors in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C. The impact of economic and environmental factors and tourism policies on the sustainability of tourism growth in China: Evidence using novel NARDL model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 30, 19326–19341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Determinants of eco-efficiency in the Chinese industrial sector. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25 (Suppl. 1), S20–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, C. Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Ecological Industry and Ecological Investment on the Economy: A Case Study of Beijing, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Ren, H.; Liu, P. Evaluation of urban ecological well-being performance in China: A case study of 30 provincial capital cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Dickinson, J.; Robbins, D.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Reviewing the carbon footprint analysis of hotels: Life Cycle Energy Analysis (LCEA) as a holistic method for carbon impact appraisal of tourist accommodation. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P. Measuring efficiency in the hotel sector. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 32, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Shao, Y. Evaluation on development efficiency of low-carbon tourism economy: A case study of Hubei Province, China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 66, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Ren, G.; Gao, X. How digitalization and financial development impact eco-efficiency? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 30, 3847–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppe, M.; Li, X.P. Productivity Measurement in Tourism: The Need for Better Tools. J. Travel Res. Int. Assoc. Travel Res. Mark. Prof. 2016, 55, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xue, Y.; Hao, Y.; Ren, S. How does internet development affect energy-saving and emission reduction? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, H.L. Socioeconomic and resource efficiency impacts of digital public services. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 83839–83859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Liang, L.; Zhai, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, X. Spatial and temporal distribution characteristics and influencing factors of tourism eco-efficiency in the Yellow River Basin based on the geographical and temporal weighted regression model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0295186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Regional Differences in Tourism Eco-Efficiency in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region: Based on Data from 13 Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangen, Z. China’s Eco-Efficiency: Regional Differences and Influencing Factors Based on a Spatial Panel Data Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Zhou, X. Emission reduction effects of the green energy investment projects of China in belt and road initiative countries. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1747947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Gui, Q.; Yang, Y.; Gong, G.; Chen, X. Tourism eco-efficiency and its influencing factors under the constraint of energy conservation and emissions reduction in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Li, L. Does digitalization always benefit cultural, sports, and tourism enterprises quality? Unveiling the inverted U-shaped relationship from a resource and capability perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, G.; Gautam, S.; Shrestha, R. Circular Economy for Nepal’s Sustainable Development Ambitions. Challenges 2025, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, Z.; Sara, M.; Markovic, V.I. Application of the DPSIR framework to assess environmental issues with an emphasis on waste management driven by stationary tourism in Adriatic Croatia. Geoadria 2021, 26, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Herrero, Á.; Gómez-López, R. Corporate images and customer behavioral intentions in an environmentally certified context: Promoting environmental sustainability in the hospitality industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, R. The coupling and coordination relationship of the digital economy and tourism industry from the perspective of industrial integration. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1182–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Specific Indicators | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Tourism resource | Number of 4A and 5A scenic spots | Unit |

| Human capital | Number of employees in the tertiary industry | Million | |

| Material capital | Tourism fixed assets | 100 million yuan | |

| Service capital | Number of starred hotels | Unit | |

| Output | Desirable output | Gross tourism revenue | 100 million yuan |

| Total tourism reception | Million | ||

| Undesirable output | Tourism carbon emission | Million t |

| Year | Northeast | East | Central Region | West | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.49 |

| 2012 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| 2013 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.51 |

| 2014 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| 2015 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| 2016 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| 2017 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | |

| lnDE | −0.0915 * | −0.143 ** | −0.134 ** |

| (0.0678) | (0.0774) | (0.3061) | |

| ln2DE | 0.00197 | ||

| (0.0653) | |||

| lnPGDP | −0.107 | −0.107 | |

| (0.1101) | (0.1102) | ||

| lnIFA | 0.0707 | 0.0708 | |

| (0.0563) | (0.0564) | ||

| lnPFE | −0.00362 | −0.00362 | |

| (0.0042) | (0.0042) | ||

| lnTPT | −0.0118 | −0.0118 | |

| (0.0287) | (0.0288) | ||

| lnPD | 0.863 ** | 0.863 ** | |

| (0.3622) | (0.3625) | ||

| lnP | −0.824 ** | −0.825 ** | |

| (0.3497) | (0.3510) | ||

| _cons | −1.118 *** | −1.223 | −1.214 |

| (0.1569) | (2.6368) | (2.6580) | |

| N | 1878 | 1868 | 1868 |

| R2 | 0.0011 | 0.0084 | 0.0084 |

| F | 1.822 *** | 1.923 *** | 1.682 *** |

| Variable | Overall (1) | Northeast (2) | East (3) | Central (4) | West (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | |

| lnDE | −0.143 ** | −0.247 | −0.0997 | 0.118 | −0.274 ** |

| (0.0774) | (0.2378) | (0.1249) | (0.1659) | (0.1448) | |

| lnPGDP | −0.107 | 0.384 | 0.115 | −0.295 | −0.332 |

| (0.1101) | (0.4015) | (0.1574) | (0.2532) | (0.2282) | |

| lnIFA | 0.0707 | −0.0105 | −0.0608 | 0.160 | 0.146 |

| (0.0563) | (0.1197) | (0.1207) | (0.1141) | (0.1314) | |

| lnPFE | −0.00362 | −0.0181 | 0.0110 * | 0.000992 | −0.0128 |

| (0.0042) | (0.0134) | (0.0065) | (0.0087) | (0.0097) | |

| lnTPT | −0.0118 | 0.141 | 0.0250 | −0.00910 | −0.0561 |

| (0.0287) | (0.1374) | (0.0446) | (0.0564) | (0.0640) | |

| lnPD | 0.863 ** | −2.566 | −1.826 * | 1.033 | 1.725 *** |

| (0.3622) | (5.6367) | (0.9490) | (0.8227) | (0.6135) | |

| lnP | −0.824 ** | 1.903 | 4.032 *** | −0.295 | −2.786 *** |

| (0.3497) | (6.5943) | (1.3665) | (0.4341) | (0.8811) | |

| _cons | −1.223 | −3.448 | −14.78 ** | −4.421 | 6.595 |

| (2.6368) | (19.5154) | (5.8279) | (6.2548) | (4.8579) | |

| N | 1868 | 200 | 655 | 470 | 543 |

| R2 | 0.0084 | 0.0251 | 0.0229 | 0.0115 | 0.0431 |

| F | 1.923 *** | 0.604 *** | 1.845 *** | 0.656 *** | 2.943 *** |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | lnTE | |

| lnDE | −0.0915 ** | −0.143 ** | −0.134 ** | −0.341 ** |

| (0.0678) | (0.0774) | (0.3061) | (0.1915) | |

| ln2DE | 0.00197 | |||

| (0.0653) | ||||

| lnDEPM25 | 0.0532 * | |||

| (0.0471) | ||||

| lnPGDP | −0.107 | −0.107 | −0.137 | |

| (0.1101) | (0.1102) | (0.1132) | ||

| lnIFA | 0.0707 | 0.0708 | 0.0566 | |

| (0.0563) | (0.0564) | (0.0576) | ||

| lnPFE | −0.00362 | −0.00362 | −0.00177 | |

| (0.0042) | (0.0042) | (0.0045) | ||

| lnTPT | −0.0118 | −0.0118 | −0.00955 | |

| (0.0287) | (0.0288) | (0.0288) | ||

| lnPD | 0.863 ** | 0.863 ** | 0.857 ** | |

| (0.3622) | (0.3625) | (0.3622) | ||

| lnP | −0.824 ** | −0.825 ** | −0.809 ** | |

| (0.3497) | (0.3510) | (0.3500) | ||

| _cons | −1.118 *** | −1.223 | −1.214 | −0.782 |

| (0.1569) | (2.6368) | (2.6580) | (2.6653) | |

| N | 1878 | 1868 | 1868 | 1868 |

| R2 | 0.0011 | 0.0084 | 0.0084 | 0.0092 |

| F | 1.822 *** | 1.923 *** | 1.682 *** | 1.842 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, H.; Chen, C.; Gan, L.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. Digital Economy’s Impact on Tourism Eco-Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310717

Shi H, Chen C, Gan L, Li T, Liu Y. Digital Economy’s Impact on Tourism Eco-Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Cities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310717

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Hong, Caiqing Chen, Lu Gan, Taohong Li, and Yijun Liu. 2025. "Digital Economy’s Impact on Tourism Eco-Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Cities" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310717

APA StyleShi, H., Chen, C., Gan, L., Li, T., & Liu, Y. (2025). Digital Economy’s Impact on Tourism Eco-Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Cities. Sustainability, 17(23), 10717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310717

_Li.png)