The Link Between ESG Factors and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Resource-Intensive Industries in Europe and the USA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

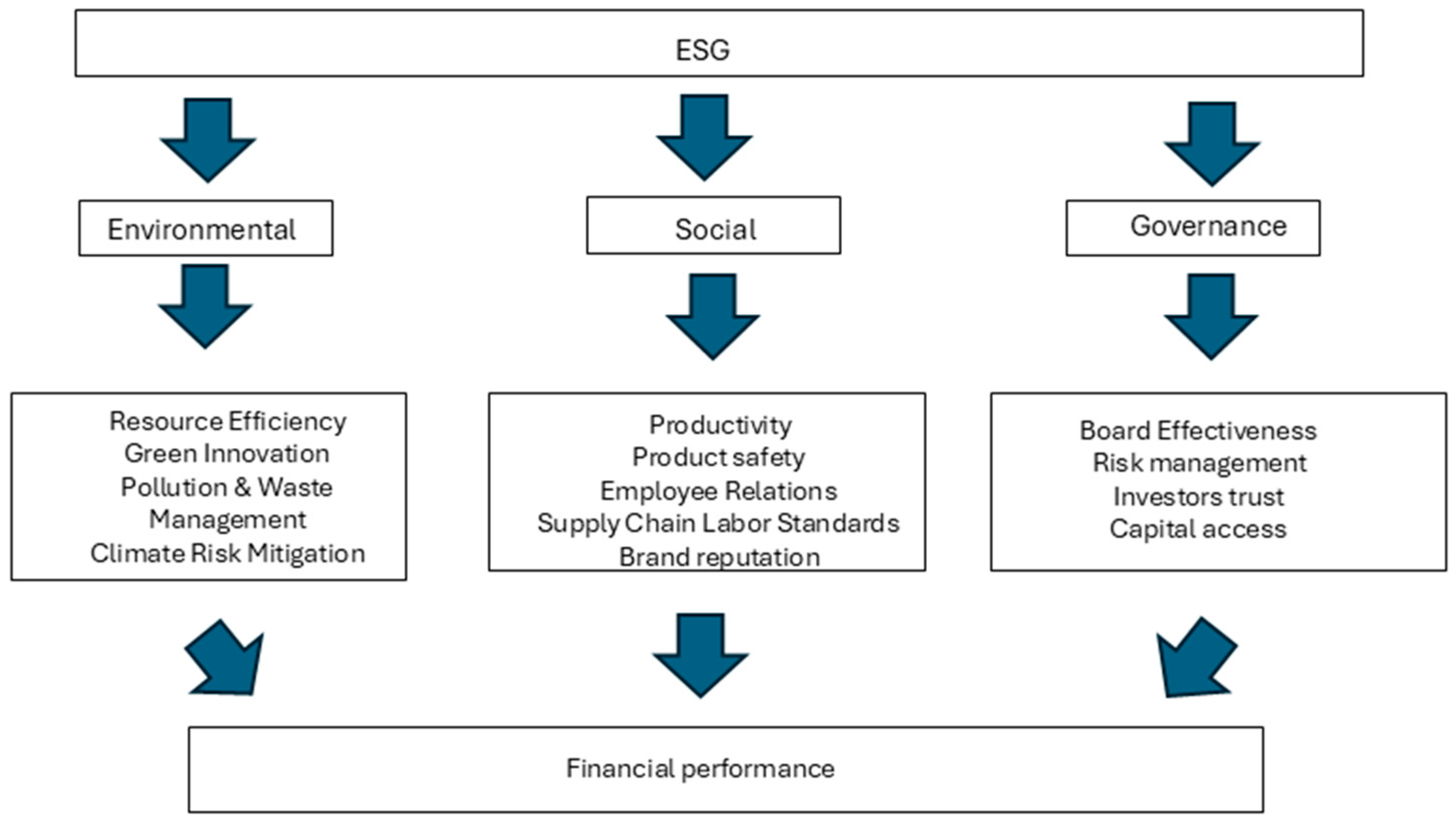

2.1. Environmental–Social–Governance Concept

2.2. ESG Regulation

2.3. Research Evidence on ESG and Financial Performance

2.3.1. Review of Empirical Studies on ESG and Financial Performance in Europe

2.3.2. Review of Empirical Studies on ESG and Financial Performance in the United States

3. Materials and Methods

- Fill-up of empty fields with adjacent data.

- Normalization of performance.

- Formulation of equations by using the robust linear regression method and their validation.

- Outlier removal and revision of probability changes in such cases.

- Validation of equations.

- R2 and adjusted R2.

- p-values of Fisher and Student tests.

4. Results

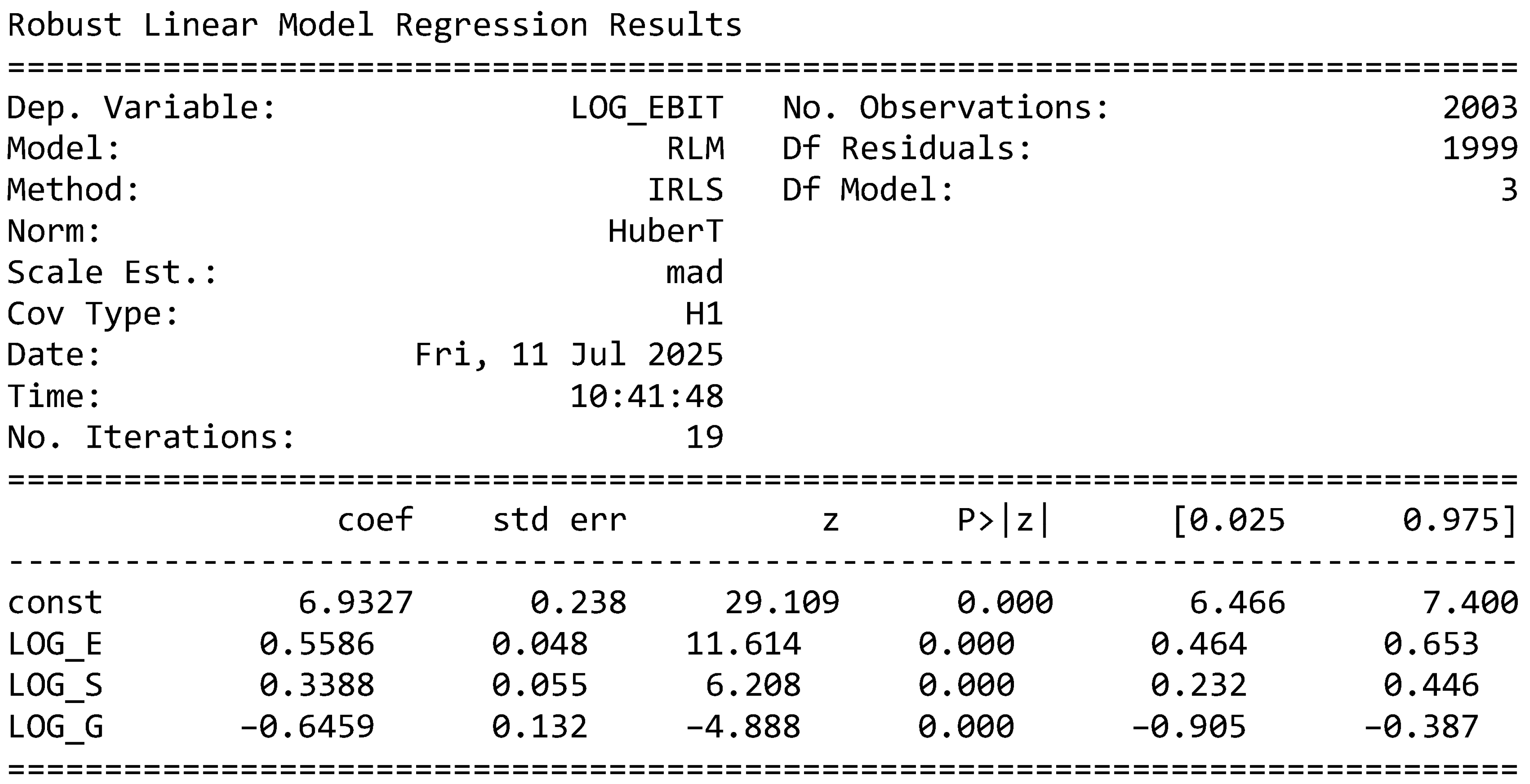

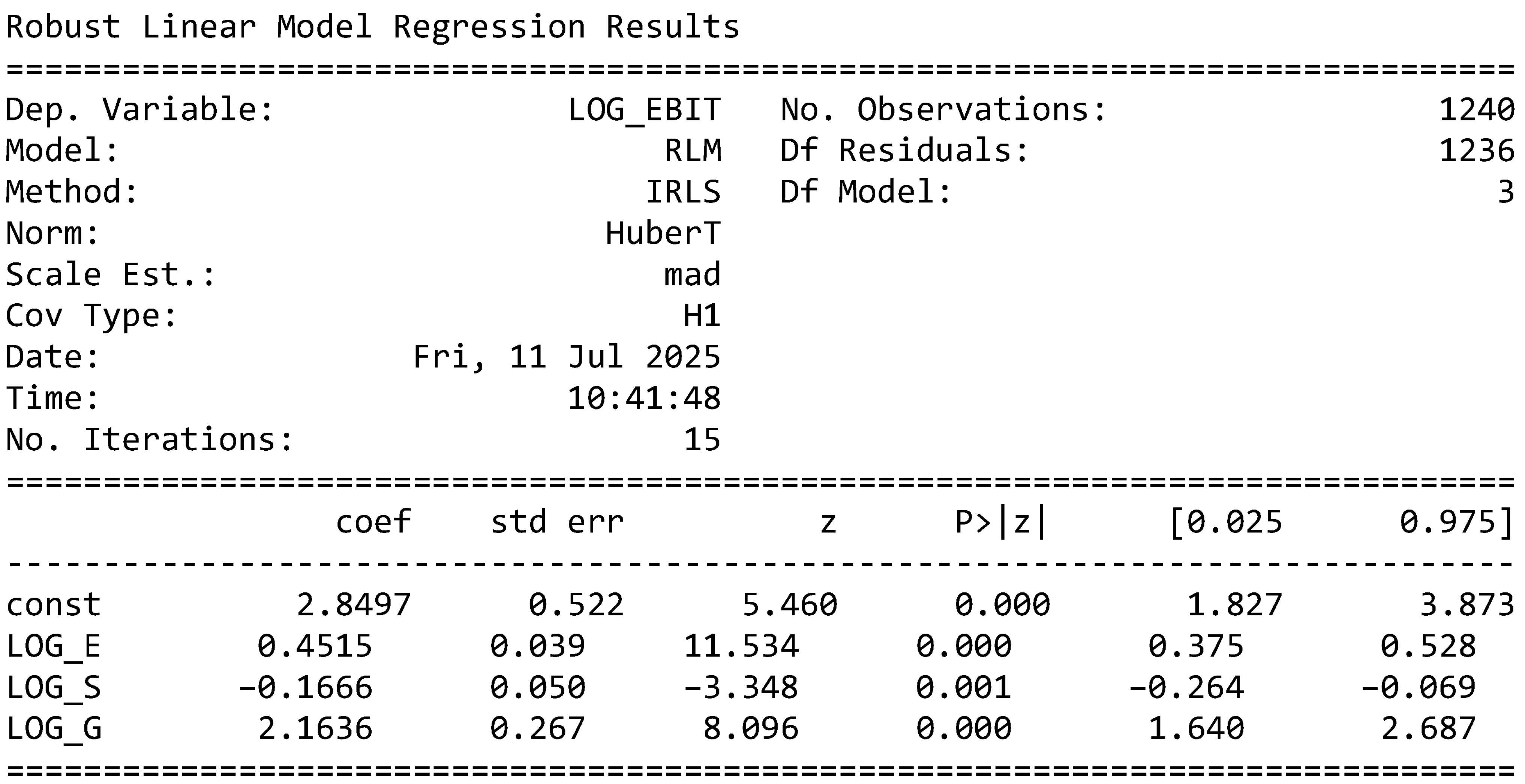

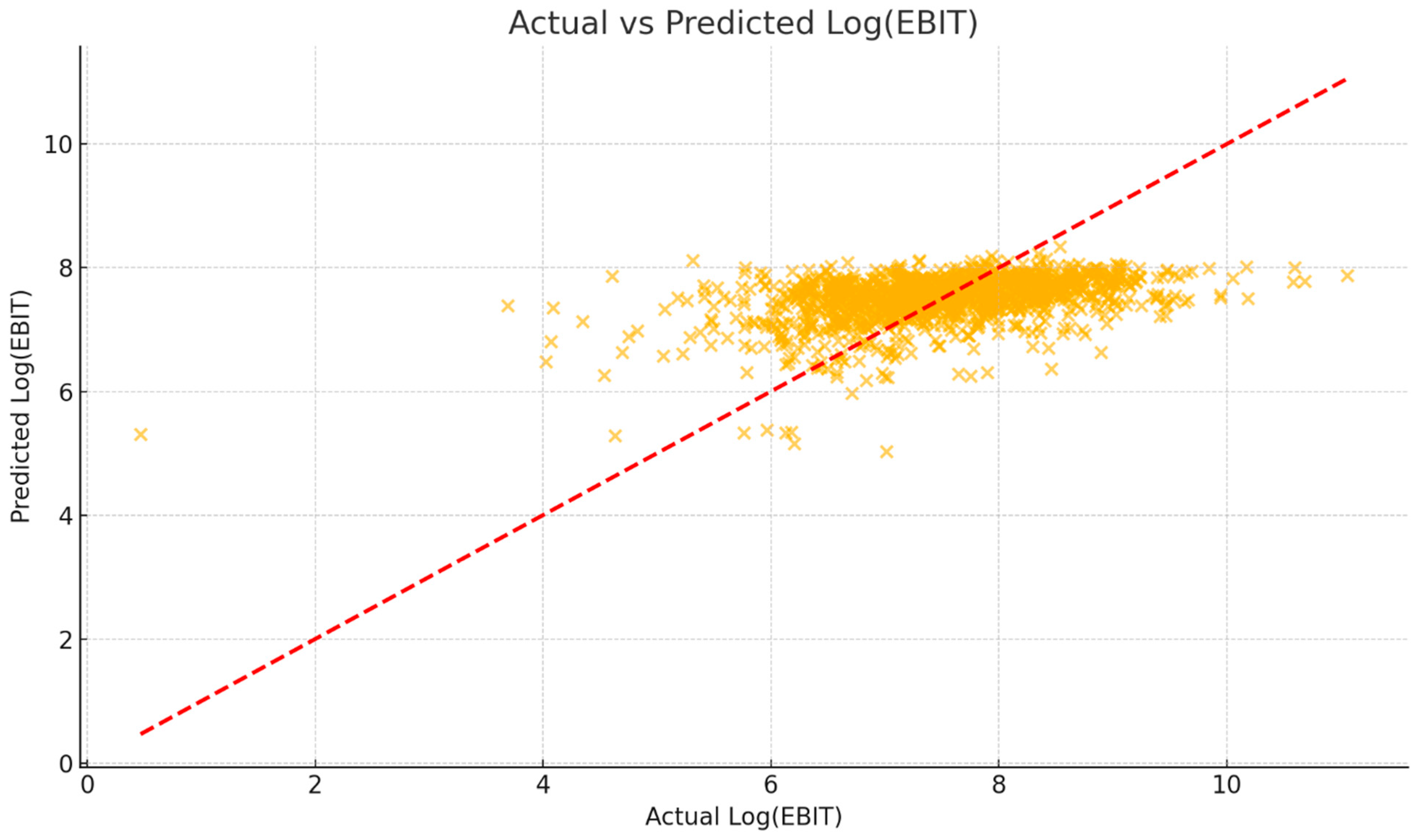

4.1. Relationship Between EBIT and the Pillars of ESG: European and USA Cases

4.2. Comparison of Sectors by Region (USA and Europe): Sector–Region RLM Analysis and Robustness Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations, Future Research, and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ESG Pillar | Indicator Categories | Examples of Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Emissions and Energy Use; Water and Waste Management; Environmental Policies and Initiatives; Sustainability and Climate Actions | Direct CO2 Emissions; Water Consumption; Emissions Reduction Initiatives; Climate Risk Mitigation, Investments in Sustainability |

| Social | Workforce and Employee Relations; Product Safety and Quality; Labor and Supply Chain Standards; Human Rights and Ethics; Training and Development | Employee Turnover %; Product Responsibility; Social Supply Chain Management; Equal Opportunity Policy; Employee Training Cost |

| Governance | Board Structure and Composition; Board Activity and Committees; Executive and Board Compensation; Ethics, Compliance, and Certifications | Independent Directors %; Number of Board Meetings; ESG-linked Compensation for Executives; Business Ethics Policy |

References

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, G. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.B.M.; Ali Hussin, H.A.A.; Mohammed, H.M.F.; Mohmmed, K.A.A.H.; Almutiri, A.A.S.; Ali, M.A. The Effect of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure on the Profitability of Saudi-Listed Firms: Insights from Saudi Vision 2030. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.M.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, X. ESG trade-off with risk and return in Chinese energy companies. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Mei, T.; Li, S. Research on the relationship between ESG disclosure quality and stock liquidity of Chinese listed companies. Green Financ. 2024, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorothy, P.; Endri, E. Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure and Firm Value in The Energy Sector: The Moderating Role of Profitability. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2024, 22, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conca, L.; Manta, F.; Morrone, D.; Toma, P. The impact of direct environmental, social, and governance reporting: Empirical evidence in European-listed companies in the agri-food sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Guo, C.Q.; Luu, B.V. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H.; Khatib, S.F. Environmental, social and governance performance disclosure and market value: Evidence from Jordan. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2024, 12, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoraki, M.-E.K.; Giaka, M.; Konstantios, D.; Patsika, V. Firms’ sustainability, financial performance, and regulatory dynamics: Evidence from European firms. J. Int. Money Financ. 2023, 131, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalih, A.A. ESG disclosure practices and financial performance: A general and sector analysis of S&P 500 nonfinancial companies and the moderating effect of economic conditions. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 13, 1506–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Li, Z. Understanding the Impact of ESG Practices in Corporate Finance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B.A.; Hamdan, A. ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 1409–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate nonfinancial disclosure, firm value, risk, and agency costs: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1149–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candio, P. The effect of ESG and CSR attitude on financial performance in Europe: A quantitative re-examination. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koundouri, P.; Pittis, N.; Plataniotis, A. The impact of ESG performance on the financial performance of European area companies: An empirical examination. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palynska, M.; Medda, F.; Caivano, V.; Di Stefano, G.; Scalese, F. The Impact of the ESG Factor on Industrial Performance. An Analysis using Machine Learning Techniques. CONSOB Sustain. Financ. Ser. 2024, 4, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Sands, J.; Rahman, H.U. Environmental, social and governance disclosure and value generation: Is the financial industry different? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jalahma, A.; Al-Fadhel, H.; Al-Muhanadi, M.; Al-Zaimoor, N. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure and firm performance: Evidence from GCC Banking sector. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA), Sakheer, Bahrain, 8–9 November 2020; pp. 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loew, E.; Endres, L.; Xu, Y. How ESG Performance Impacts a Company’s Profitability and Financial Performance; European Banking Institute Working Paper Series No. 162; EBI: Frankfurt, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeker, Y.; Güngör, N. Does ESG Performance Impact Financial Performance? Evidence From the Utilities Sector. Muhasebe Bilim Dünyası Dergisi 2022, 24, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, A.; Petrov-Nerling, G. Systemic ESG risks: Industrial analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 221, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyusein, A.; Cek, K. ESG strategies and corporate financial performance: A comparison of the US energy and renewable energy industries. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2025, 19, 977–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, A.; Pitenko, K.; Karminsly, A. Analysis of the Industry-Specific Characteristics of ESG Components in Company Ratings. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 242, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. ESG disclosure and firm performance: A bibliometric and meta analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 61, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskantar, M.; Zopounidis, C.; Doumpos, M.; Galariotis, E.; Guesmi, K. Navigating ESG complexity: An in-depth analysis of sustainability criteria, frameworks, and impact assessment. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoepfel, I.; Hagart, G. Future Proof?: Embedding Environmental, Social and Governance Issues in Investment Markets: Outcomes of the Who Cares Wins Initiative, 2004–2008; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/681662?ln=en&v=pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Serafeim, G. Purpose and Profit: How Business Can Lift Up the World; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2022; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi, E.; Burchi, A.; Goodell, J.W.; Paltrinieri, A. Stakeholders and regulatory pressure on ESG disclosure. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 103, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Legal Insights. Environmental, Social & Governance Law USA. 2025. Available online: https://iclg.com/practice-areas/environmental-social-and-governance-law/usa (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- European Commission. Corporate Sustainability Reporting. 2025. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/capital-markets-union-and-financial-markets/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en#what (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1760 on Corporate Sustainability due Diligence and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Regulation (EU) 2023/2859. 13 June 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj/eng (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Schwartz, J. Transnational ESG: The Impact of EU Sustainability Directives on US Law and Policy. J. Law Political Econ. 2025, 5, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchako, T.; Benjamin, L. ESG Backlash in the United States-Investor Concerns or “Red Scare”? J. Law Political Econ. 2025, 5, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Legislature. California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010; Cal. Civ. Code § 1714.43; California Legislature: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.; Managi, S. Disclosure or action: Evaluating ESG behavior towards financial performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Arslan, S.; Birkan, A.O. ESG practices and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Z. ESG, Cultural Distance and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Chinese Multinationals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oanh, V.T.K.; Thao, T.P.; Anh, N.T.; Chi, N.H.; Nhi, D.T.Y.; Trang, M.T.H. Banks’ financial performance: A study of environmental, social, and governance dimensions. Risk Gov. Control Financ. Mark. Inst. 2025, 15, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, J.; Rivelles, R.; Sapena, J. Corporate governance and financial performance: The role of ownership and board structure. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Zeng, Q.; Zhu, B. Effect of ESG performance on the cost of equity capital: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 83, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.; Wei, Y.-M.; De La Vega Navarro Garg, A.; Garg, A.; Hahmann, A.N.; Khennas, S.; Azevedo, I.M.L.; Löschel, A.; Singh, A.K.; Steg, L.; et al. Energy Systems. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobal, M.; Lughi, V. Sustainability in the Energy System and in the Industrial System. In Quantitative Sustainability; Fantoni, S., Casagli, N., Solidoro, C., Cobal, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, M.; Radulescu, M.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Pollution and electricity price in the EU Central and Eastern European countries: A sectoral approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 95917–95930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beelitz, A.; Cho Ch Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M. Measuring CSR Disclosure when Assessing Stock Market Effects. Account. Public Interest 2021, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Kuźniarska, A.; Makieła, Z.J.; Sławik, A.; Stuss, M.M. Does ESG Reporting Relate to Corporate Financial Performance in the Context of the Energy Sector Transformation? Evidence from Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, V.; D’Ecclesia, R.; Levantesi, S. Firms’ profitability and ESG score: A machine learning approach. Spec. Issue Probabilistic Stat. Methods Commod. Risk Manag. 2023, 40, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnini Pulino, S.; Ciaburri, M.; Magnanelli, B.S.; Nasta, L. Does ESG Disclosure Influence Firm Performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerciello, M.; Busato, F.; Taddeo, S. The effect of sustainable business practices on profitability. Accounting for strategic disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 802–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R.A.; Khan, M.K.; Anwar, W.; Maqsood, U.S. The role of audit quality in the ESG-corporate financial performance nexus: Empirical evidence from Western European companies. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, S200–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiraj, R.; Demiraj, E.; Dsouza, S. The Moderating Role of Worldwide Governance Indicators on ESG–Firm Performance Relationship: Evidence from Europe. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, M.; Falcão, L.; Robaina, M.; Madaleno, M. The Impact of ESG Factors on Financial Performance in the European Energy Sector. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Lisbon, Portugal, 27–29 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridou, G.; Doumpos, M.; Lemonakis, C. Relationship between ESG and corporate financial performance in the energy sector: Empirical evidence from European companies. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 873–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanday, J.; Ajour El Zein, S. Higher expected returns for investors in the energy sector in Europe using an ESG strategy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1031827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, F.; Pizzi, S.; Lippolis, S. Sustainability reporting and ESG performance in the utilities sector. Util. Policy 2023, 80, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Nur, T.; Topaloglu, E.E. Environmental, Social, and Governance Sustainability Management and Financial Outcomes: Evidence from US Tech Companies. In Assessment of Social Sustainability Management in Various Sectors; Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes Series; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademi, B.; Klungseth, N.J. Does it pay to deliver superior ESG performance? Evidence from US S&P 500 companies. J. Glob. Responsib. 2022, 13, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. ESG Indicators for Sectors. Data Set. Bloomberg Database. 2024. Available online: https://libguides.utsa.edu/c.php?g=1293624&p=9763131 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Wong, W.C.; Batten, J.A.; Mohamed-Arshad, S.B.; Nordin, S.; Adzis, A.A. Does ESG certification add firm value? Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 39, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rosing, M.; Shepperson, L.; Czichos, H. Chapter 44—External ESG auditing: The what, why, who, and how. In The Sustainability Handbook; von Rosing, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 1, pp. 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, S.; Tron, A.; Colantoni, F.; Savio, R. Sustainability disclosure and IPO performance: Exploring the impact of ESG reporting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q. How does ESG disclosure improve stock liquidity for enterprises—Empirical evidence from China? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspects | EU | US |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate sustainability reporting | CSRD + ESRS (double-materiality assessment and value-chain data). EU Taxonomy—criteria for environmentally sustainable activities. | Disclosure obligations are largely driven by the SEC, stock exchange listing rules, and voluntary frameworks (such as GRI, SASB, and TCFD). |

| Sustainable chain control | CSDDD—requires large EU and certain non-EU companies with substantial EU turnover to implement risk-based human rights and environmental due diligence across their “chain of activities,” maintain grievance mechanisms, and adopt transition plans. | Regional level—[37] companies face due diligence duties primarily regarding conflict minerals, forced labor, and imports linked to human rights violations (fragmented). |

| Emission management | The EU Emission Trading System was launched in 2005 and is still in force to control the emission levels of companies. | Regional programs and state-level initiatives that serve as the closest equivalents (California Cap-and-Trade, etc.). |

| Impact on Financial Performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/ Country | Sector | ESG (Overall) | E | S | G | Source |

| China | Manufacturing | Positive | N/A | N/A | N/A | [40] |

| Vietnam | Banking | Positive | N/A | N/A | N/A | [41] |

| Global | Mixed | Positive | N/A | N/A | N/A | [43] |

| Europe and the USA (combined) | Mixed | U-shaped (negative at first, positive later) | Positive | U-shaped (negative at first, positive later) | U-shaped (negative at first, positive later) | [17] |

| Global | Utility | No impact | No impact | No impact | No impact | [22] |

| Global | Mixed | Negative on oil, gas, and mining | Negative | N/A | N/A | [23] |

| Turkey | Mixed | N/A | Negative | Positive | Positive | [39] |

| Global | Mixed | N/A | N/A | N/A | Negative | [42] |

| Authors | Data, Methods, Databases | Period | Indicators | Results | Keywords (Sector, Result) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | US companies in the manufacturing and service industries. SP-500, dynamic panel data model, Bloomberg, and Thomson Reuters. | 2010–2019 | ROA, ESG pillars | Social and governance pillars positively impacted ROA. | Manufacturing—S, G positive |

| [22] | 325 companies worldwide are listed in Refinitiv’s Thomson Reuters ASSET4, EIKON, and Datastream of the utilities sector; regression analysis. | 2010–2019 | ROA, ESG score | ESG performances of the companies have no impact on their financial performance. | Utility—negative |

| [23] | 270 global companies in selected industries; regression analysis, Thomson Reuters. | 2007–2021 | EBIT, ESG score | In the oil, gas, and mining sectors, ESG scores have been linked to poorer financial outcomes. | Oil, gas, and mining —negative |

| [24] | US energy and renewable energy industry companies; panel data model. | 2013–2023 | ROA, ESG score | In both sectors, overall ESG scores had a positive impact on ROA. | Energy—positive |

| [25] | According to Thomson Reuters, there are 60 companies from European countries in the Schengen area. | 2015–2022 | ROA, ESG pillars | The materials and essential goods industry—impact is positive. Energy industry E—positive impact. | Materials—positive. Energy—positive |

| Steps | Aim | Outputs | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Revise the panel data | Retrieve the data available at the Bloomberg (2024) [60] data lake and normalize it. | The data describing the European and the USA regions were grouped for further investigations. | ESG scores describing the European and the USA regions were analyzed. |

| 2. Formation of a robust linear model (RLM) | Identify ESG impact on EBIT and check the formulated hypothesis. | Revision of regression results and evaluation of the impact’s significance. | Analyze ESG impact by regions. |

| Statistic | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Observations | 2003 | Excellent sample size |

| p-values (all variables) | <0.001 | All terms are highly significant |

| Mean of residuals | +0.0367 | Near-zero; slightly positive bias |

| Std. dev. of residuals | 1.2993 | Slightly higher dispersion than one |

| Residual range | −6.09 to +4.01 | Still well-distributed |

| Iterations (IRLS) | 19 | Efficient convergence |

| Statistic | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Observations | 1240 | Good sample size |

| p-values (all variables) | <0.01 | Statistically significant |

| z-statistics | > | 3 |

| Mean of residuals | −0.0036 | Near-zero → good centering |

| Std. dev. of residuals | 0.8830 | Acceptable dispersion |

| Residual range | −4.84 to +3.18 | No extreme outliers dominate |

| Iterations (IRLS) | 15 | Stable convergence |

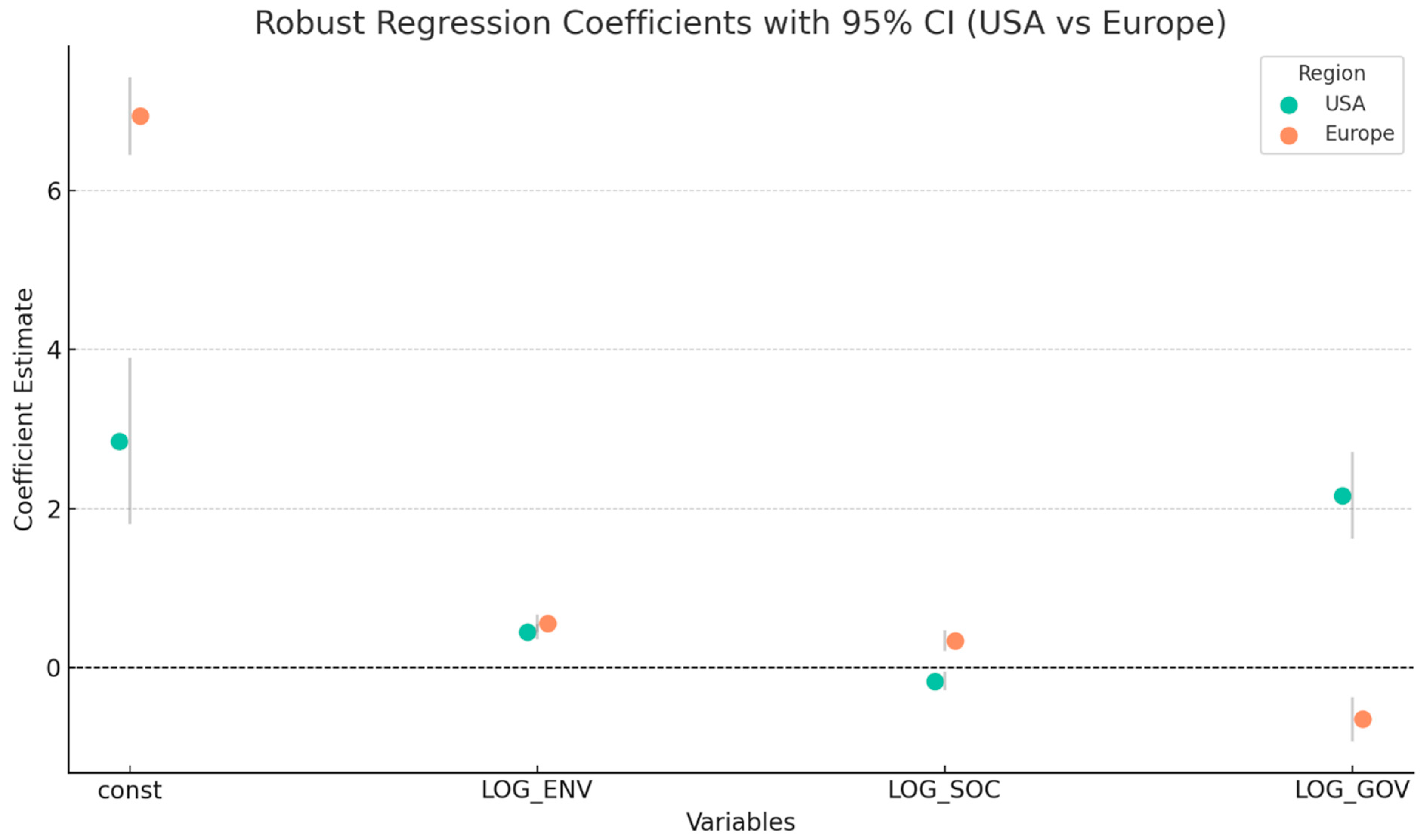

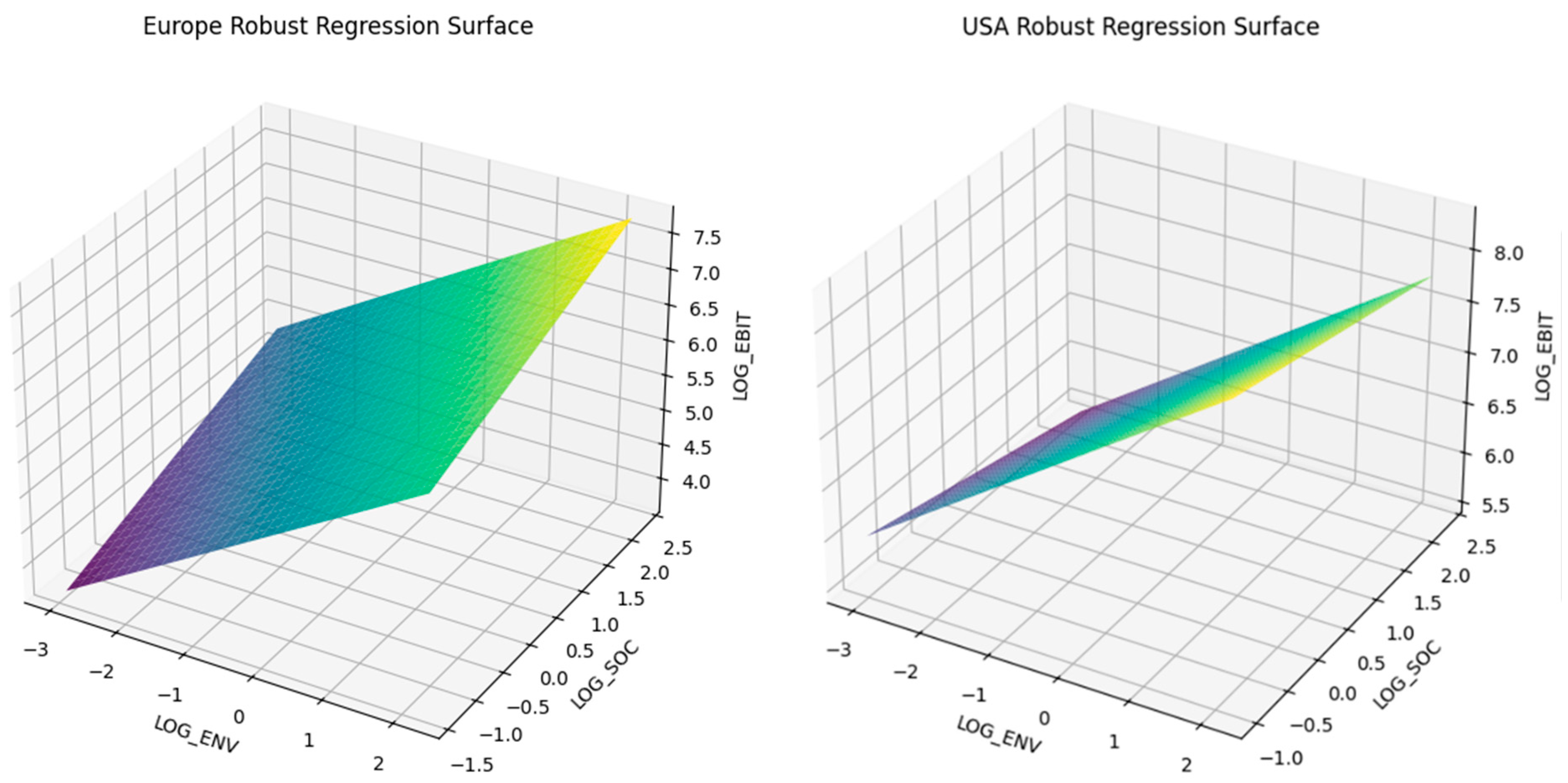

| Factor | European Region (β, p-Value) | USA Region (β, p-Value) | Interpretation Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOG_S | β = 0.338, p = 0.000 | β = −0.166, p = 0.001 | Positive effect in the European region case and negative effect in the USA region case, suggesting differences among the regions and the relationship with the social factor (H1b confirmed). |

| LOG_EL | β = 0.558, p = 0.000 | β = 0.451, p = 0.000 | Positive and statistically significant effect is evident in both regions. Environmental gains consistently have positive effect on profitability (H1a confirmed). |

| LOG_G | β = −0.645, p = 0.000 | β = 2.163, p = 0.000 | Strongly negative in Europe and strongly positive in the USA, reflecting contrasting governance impacts across regions (H1c confirmed in the USA, rejected in the European case). |

| Region | Sector | N | Log_E Coefficient (p) | Log_S Coefficient (p) | Log_G Coefficient (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Energy | 136 | 0.082 (0.657) | 1.747 (8.45 × 10−13) | 2.461 (1.14 × 10−5) |

| Europe | Industrial | 1097 | 0.580 (1.45 × 10−20) | 0.139 (0.071) | −1.247 (6.36 × 10−12) |

| Europe | Materials | 524 | 0.683 (4.64 × 10−11) | 0.229 (0.013) | −0.328 (0.125) |

| Europe | Utilities | 246 | 0.387 (4.14 × 10−4) | 0.338 (0.010) | 0.305 (0.482) |

| USA | Energy | 174 | 0.645 (9.48 × 10−4) | 0.429 (0.054) | 2.432 (0.021) |

| USA | Industrial | 541 | 0.397 (1.54 × 10−14) | −0.330 (1.01 × 10−5) | 3.035 (8.47 × 10−14) |

| USA | Materials | 248 | 0.542 (2.01 × 10−8) | 0.051 (0.579) | 1.666 (0.003) |

| USA | Utilities | 277 | 0.424 (6.53 × 10−8) | 0.243 (0.068) | −0.066 (0.891) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burinskienė, A.; Grybaitė, V.; Lapinskienė, G. The Link Between ESG Factors and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Resource-Intensive Industries in Europe and the USA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310714

Burinskienė A, Grybaitė V, Lapinskienė G. The Link Between ESG Factors and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Resource-Intensive Industries in Europe and the USA. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310714

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurinskienė, Aurelija, Virginija Grybaitė, and Giedrė Lapinskienė. 2025. "The Link Between ESG Factors and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Resource-Intensive Industries in Europe and the USA" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310714

APA StyleBurinskienė, A., Grybaitė, V., & Lapinskienė, G. (2025). The Link Between ESG Factors and Corporate Profitability: Evidence from Resource-Intensive Industries in Europe and the USA. Sustainability, 17(23), 10714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310714