1. Introduction

In an era of rapid technological advancement and mounting global climate challenges, the transition to a low-emission economy is imperative. A key factor in the success of this process is the redefinition of human capital to encompass specialised knowledge and skills, as well as a society’s willingness and ability to accept and implement innovative changes in the new model of a transformative energy economy. While it may seem that the approach to human resources has remained largely unchanged for decades, the accelerating pace of change and intensifying global competition require swift action to foster the development of human capital. This is particularly important for the European socio-economic space [

1], where deficits such as the lack of basic green skills in key sectors are common place. According to Cedefop analyses (2021) and IEA reports (2022), there is a shortage of qualified renewable energy and heat pump installers, energy efficiency technicians, and building renovation specialists [

2,

3]. This shortage directly hinders the achievement of transition goals, as these technologies, although available, cannot be implemented quickly and on a large scale. This qualitative and systemic shortage reveals a lack of engineers and managers who are experts in energy, digitalisation (AI and big data), and cybersecurity. The ability to integrate distributed renewable energy sources and manage grid complexity is directly limited by the shortage of personnel with this unique set of interdisciplinary competencies.

The third area of the deficit relates to the lack of behavioural and social competencies, which manifests in two ways. Firstly, social resistance to key renewable energy investments (e.g., wind turbines) is often the result of decision-makers’ inability to build trust and communicate with local communities. Secondly, in regions dependent on fossil fuels, the process of retraining workers encounters motivational and social barriers as well as technical ones. Therefore, the human capital required for an energy-transforming economy must include the ability to manage change and accept energy policies, which is crucial to overcoming the bottleneck in the permitting process [

4]. Strongly advocating the implementation of sustainable development principles while simultaneously striving to maintain a balance between the three priorities of environment, society and economy will not deliver the expected results unless key resources are properly defined and methods for measuring them are developed that reflect changing operating conditions.

The issue of human capital has been a popular research topic for years, seeking to answer questions about the factors that cause disparities in socio-economic development levels and the varying dynamics of development processes worldwide [

5,

6,

7]. Although current research provides extensive knowledge in this area, ongoing climate change necessitates a shift from a conventional energy source-based model to a low-emission model. Therefore, it is essential to revise the current approach to human resources so that they can play a pivotal role in the development of this new green economy model.

A review of the literature on the role of human capital in an economy undergoing energy transformation reveals a significant research gap. Although numerous studies address the issue of a low-emission economy, attempts to connect human capital to this new economic model are relatively rare. Given the current state of knowledge, researchers of socio-economic development processes should be interested not only in redefining human capital, but also in understanding its essence in the new economic model. The main problem is the operationalisation of human capital, i.e., selecting appropriate empirical variables to express its essence in the new economic model. Therefore, identifying the optimal measure that would enable the universal diagnosis and assessment of this resource at local, regional and international levels, and which would be appropriate for a new economic model based on green energy, is crucial.

It is estimated that the interpretive value of human capital indicators used in the past has become somewhat outdated. This is because they were based on empirical variables that adequately expressed the essence of this resource in relation to the economic model adopted (e.g., a knowledge-based economy). However, in the current conditions of ongoing energy transformation, these indicators may be inaccurate. Therefore, the current approach must be revised and new empirical variables must be identified that adequately capture the essence of human capital in an economy undergoing energy transformation.

This article contributes to the ongoing discussion in this area and fills a gap in the existing literature. The general research problem is formulated as a question about how to express the essence of human capital in an economy undergoing energy transformation and whether there are any appropriate metrics for measuring it based on this research approach. The lack of similar research and key knowledge about the role of human capital, particularly with regard to measurement methods in an economy undergoing energy transformation, necessitates revising the approach to expressing its essence in a new economic model, thereby justifying research in this area. In this sense, the article takes an innovative approach, albeit with certain limitations.

The main empirical objectives are firstly to diagnose the overall level of human capital in the energy transition economy based on the original synthetic measure, HCIe, and secondly to analyse and assess the variation in its spatial distribution across the European socio-economic landscape, which serves as a foundation for developing a targeted policy typology directly linked to the identified cluster profiles and their specific weaknesses. The article also analyses and assesses variations in the spatial distribution of this resource across the European socio-economic landscape, exploring its internal structure in terms of innovation and creativity, health, the labour market, education and quality of life. The main sources of data used to construct the synthetic measures were international databases: IRENA, OECD, EUROSTAT and the World Bank. These databases provide a classical approach to the human capital index, which was the subject of comparative analyses. 26 European countries were selected to measure and explore the internal structure of human capital within the socio-economic landscape. The main selection criteria were the availability, completeness and continuity of the data used to construct the synthetic measures.

In light of the observed changes in international competition, this article addresses a difficult yet important and timely issue. It contributes to further scholarly discussion on the role of key factors in socio-economic development—specifically, human capital—in the context of energy transformation in Europe and globally. The article attempts to indicate the direction of the further evolution of economic thought, with a particular focus on practical methods for diagnosing this resource and examining the social potential required to foster local, regional and global competitiveness within an economy undergoing energy transformation. It is important to emphasise that the article proposes an innovative approach that combines the classic concept of human capital with a new approach stemming from the inevitable and ongoing process of socio-economic development in an era of energy transformation. This addresses the existing need to expand knowledge in the area of defining, diagnosing and measuring human capital in a new era.

2. Human Capital in a Renewable Energy Economy: Directions for Development and Challenges

2.1. Theoretical Framework for Research on Human Capital in the Energy Transition

This study is based on an integrated theoretical framework that goes beyond the traditional macroeconomic approach to human capital, intentionally combining four key perspectives. This interdisciplinary synthesis is essential in order to adequately reflect the complexity of human capital in an economy undergoing an energy transition, and to justify the multidimensional construction of a synthetic measure.

2.1.1. Human Capital Theory (HCT)

This study is based on the classic Human Capital Theory formulated by Becker and Schultz [

6,

7]. According to this theory, investments in education, vocational training and health constitute intangible capital, increasing the productivity and innovation of individuals and entire economies. In the context of current European programmes, such as the Green Deal, the assumptions of this theory must be adapted to the specific nature of the green economy. Energy transformation requires investment in so-called ‘green skills’, which encompass not only narrow technical skills (e.g., PV panel installation), but also a broad spectrum of competencies (e.g., circular system design, energy auditing and data management [

8,

9]. Therefore, the developed HCIe human capital measure is assumed to reflect not only formal education, but also the overall efficiency and potential of the labour market, including health indicators. These indicators are fundamental to determining the effectiveness and sustainability of human capital.

2.1.2. The Theory of Technological Innovation Systems (TIS)

As energy transition is primarily a technological change, the conceptual framework of this study draws on the TIS theory, as formalised by Hekkert et al. [

10]. According to this framework, innovation is the result of dynamic interactions within a system rather than a single invention. The functioning of a TIS depends on seven key functions, such as knowledge generation, networking and search management. Human capital plays a pivotal role in this system [

11]. Deficits in human capital in European countries are strongly associated with the inefficiency of TIS functions, including weakened networking. This is evidenced by the lack of qualified specialists, which hinders collaboration between engineers, companies, and research centres. This results in a shortage of guidance skills for searches, meaning there are ultimately insufficient experts capable of strategically identifying the most promising technological paths (e.g., hydrogen vs. batteries). In this context, the HCI measure must consider system and network competencies, which are critical to the effectiveness of TIS.

2.1.3. Socio-Technical Transition Theory (Multi-Level Perspective, MLP)

From a socio-economic perspective, Socio-Technical Transition Theory (MLP) appears to be pivotal. It views transformation as a complex, long-term process in which new technologies (niches) must overcome established technical and institutional structures (regimes) amid broad changes (landscapes) [

12,

13]. The MLP argues that human capital must be considered in terms of social embeddedness and agency. Transformation will not be successful without social acceptance and the administration’s ability to manage systemic change [

14]. According to MLP, deficiencies in HCIe, such as a lack of communication and trust-building skills, are a key cause of bottlenecks as they lead to social resistance.

2.1.4. Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory

The socioeconomic and behavioural aspects are reinforced by the VBN theory. According to VBN, pro-environmental decisions and behaviours (e.g., purchasing an electric car or supporting a local wind farm) are preceded by a specific sequence: values shape beliefs, which lead to norms and ultimately actions [

15,

16]. In the context of transformation, the HCIe deficit encompasses not only competencies, but also behavioural readiness and policy acceptance. Incorporating the VBN perspective into the study justifies why HCIe indicators must indirectly reflect social and institutional capacity for adaptation and changing attitudes, which are fundamental to the success of the entire European Green Deal.

This article proposes the integration of the above theoretical framework, in which human capital is treated not solely as an individual resource, but as a systemic variable crucial to the energy transition. This capital acts as an enabling mechanism that firstly provides the necessary skills and knowledge for developing and diffusing innovations (TIS); secondly enables the institutional adaptation required for transitioning between regimes (MLP); and thirdly encompasses behavioural readiness (VBN), i.e., the attitudes and social norms necessary for social acceptance and demand for green solutions. This deliberate integration of the four perspectives forms the basis of the multidimensional, contextual construction of the HCIe index.

2.2. Conceptual Rationale for the HCIe Measure: Integrating the HCT, TIS, MLP and VBN Frameworks

There are many human capital measures in the literature, such as the World Bank’s HCI, as well as indicators describing so-called green human capital. However, none of these measures are designed to capture the context of the energy transition comprehensively by integrating innovation and behavioural aspects simultaneously. In this sense, the proposed synthetic HCIe measure is advantageous due to its multidimensionality and focus on the energy transition (see

Table 1 for a comparison).

As illustrated in

Table 1, existing human capital measures, including the World Bank’s HCI, are inadequate for capturing the systemic and contextual nature of the energy transition. In contrast, the HCIe addresses a fundamental theoretical and contextual shortcoming. While the classic HCI measures productive potential based on health and education, the HCIe is a purpose-built indicator measuring the adaptive capacity of a socio-economic system to the transition. It achieves this by integrating classic human capital theory (HCT) with TIS, MLP and VBN theories into a single indicator. This integration enables an empirical assessment of not only the availability of skills (HCT), but also the systemic mechanisms (TIS/MLP) and level of acceptance (VBN) required for a successful sociotechnical transition. The approach used to construct the HCIe measure is an important step towards a holistic diagnosis of human resources in light of the complex energy transition process requirements, at both the national and regional levels. At this point, it seems appropriate to refer to the institutions that specifically study Green Skills. While not without its flaws, the HCIe measure avoids the limitations of measures developed by institutions such as CEDEFOP, OECD and EUROSTAT. While these are important for analysing the labour market, they primarily focus on technical and professional supply. In contrast, HCIe broadens this perspective, integrating the VBN aspect with the systemic TIS/MLP measures. This allows for a holistic diagnosis of countries’ preparedness for transformation, considering both existing skills and the societal willingness to utilise them (see

Table 2).

By contrast, the 2030 Agenda indicators (e.g., SDG 7 and SDG 13) are not the typical measures used to express or measure human capital. Various institutions use them to form a reporting and monitoring framework for many global, regional and national organisations. SDG 7 focuses on access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy (

Table 3), while SDG 13 focuses on tackling climate change and its effects (

Table 4). A key advantage of the HCIe measure over the SDG measures is that the latter are distributed and descriptive, whereas the former is synthetic and analytical. SDG measures are collected, but not aggregated into a coherent measure of human capital, making them less suitable for clustering analysis, such as that undertaken in this article.

In summary, unlike generic measures of human capital that focus on basic human resources (e.g., the World Bank’s HCI), HCIe is a contextual measure designed to capture the holistic requirements of the energy transition process. Integrating the VBN and TIS/MLP dimensions within human capital theory provides an analytical bridge between individual capabilities (in the classical theory’s approach) and the dynamics of systemic change (MLP), a feat unattainable using single-dimensional indicators of so-called “green skills.” The advantage of HCIe over other such measures lies in its analytical function, which directly addresses the need to formulate and implement appropriately targeted policy support instruments. By aggregating diverse but complementary dimensions, HCIe not only classifies countries as good or bad in transition (as a simple ranking would do), but also identifies a unique profile of weak links within each cluster (e.g., the diagnosis of ‘strong TIS and weak VBN’ for Cluster B). This level of analytical typology is crucial for formulating targeted policy recommendations, which is impossible when using general measures that could erroneously suggest a uniform intervention for all countries. In this context, the HCIe indicator should be assessed as a decision-making tool, not simply as a statistical one.

2.3. The Role of Human Capital in Socio-Economic Development in Light of Current Strategic Documents in Europe Undergoing Energy Transformation

There is a general consensus that the socio-economic development of European countries can only be realised by future generations if there is coherence between the three components of development: the natural environment, society, and the economy. This coherence is guaranteed by sustainable development, a concept that strikes a balance between economically viable actions and those that are ecologically safe and socially acceptable [

17].

The current goals of this strategy are defined by the UN’s Agenda 2030 programme [

18], which, together with the Paris Agreement [

19], aims to achieve long-term effects such as reducing social exclusion and poverty, social inequalities, and improving healthcare and the state of the natural environment. It also aims to increase the role of human and social capital in development. However, the Draghi report emphasises that Europe’s long-term prosperity and competitiveness must be based on an ambitious investment plan, calling for additional annual investments of EUR 800 billion to accelerate the green and digital transformation [

20].

Energy transformation involves switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency. This directly affects all three aspects of activity. It is a process that goes beyond ideas and states of mind. It is a real challenge that requires specialist knowledge and social awareness. High-quality human capital plays a key role in this process, i.e., individuals who actively, consciously and preferably voluntarily participate in the changes. Unfortunately, the issue of voluntariness is often controversial, resulting from low levels of education, a lack of motivation, and negative attitudes towards change. However, the biggest barrier seems to be the economic factor. Individual choices, such as a household’s decision to purchase a wood stove or heating technology based on renewable energy sources, are often influenced by financial constraints. What is beneficial for the climate and the environment is unfortunately not always accessible to individuals. This raises questions about the rationality of individual decisions, particularly in situations of material deprivation.

The problem of priorities—social, economic and environmental—has already been highlighted in many earlier works in the context of implementing the principles of sustainable development in European Union countries [

21]. Just as the level of sustainability achieved was the result of the different political priorities of individual countries, we should expect to observe differences in the currently energy-transforming European economies. Some countries, despite complying with environmental restrictions and meeting basic human needs, do not and will not guarantee social justice. Conversely, others are able to meet basic human needs in addition to fulfilling environmental recommendations and ensuring social balance. For these countries, the priority is to eliminate extreme poverty and economic deprivation. Therefore, to achieve full sustainable development, policies and institutions that support economic growth and eliminate these inequalities are key.

From a macroeconomic perspective, energy transformation is a fundamental, long-term process of shifting from a fossil fuel-based energy system to a low-emission system based mainly on renewable energy sources (RES). This process involves real decisions and actions. The aim is to guarantee higher energy efficiency and security for societies and future generations than before. At the level of the European Union, a new binding target has been set to increase energy efficiency by 11.7% by 2030. This means that EU Member States will have to save an average of 1% per year by 2030. They will also have to prioritise improving energy efficiency for those affected by energy poverty [

22,

23].

This second issue is extremely important from the perspective of the issues addressed in this article. However, it seems that relatively little in the global discussion and in the strategic goals of states addresses the issue of the individual (human) and decisions at the individual level. Economic theory, including the theory of human capital, has provided scientific evidence many years ago that it is this resource that determines economic success and success at the local, regional and global level [

6,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Deficiencies of this endogenous resource mean that even currently, certain areas and regions in highly developed countries, referred to as problematic or peripheral, experience serious development problems. They have serious problems in creating the so-called critical mass and initiating development processes [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Social potential plays a key role in these processes, particularly at the local, rural level. The pillars of social potential are social capital and human capital. Regardless of the approach adopted, it is worth noting that properly diagnosing and effectively using internal potential can stimulate development in areas with deficits, including less developed areas [

34,

35] less industrialised or revitalised areas (e.g., post-industrial areas [

36,

37] rural areas [

38,

39,

40,

41] and peripheral areas. In this socio-economic revolution, it is expected that this resource will play a key role in initiating development processes at local and national levels. Therefore, it is worthwhile delving deeper into this research to find answers to the question of what resources an economy undergoing energy transformation needs. It is also crucial to redefine and operationalise the concept in light of the new challenges posed by the new economic model. This will enable us to determine which metrics to use to measure the level of this resource while also enabling international comparative analyses. This will provide decision-makers with the knowledge they need to plan and implement development programmes that support human capital development.

In response to concerns about the future energy security of future generations of Europeans, the European Commission has adopted a package of legislative proposals to adapt EU climate, energy, transport and tax policies. The aim is to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. The European Green Deal is a comprehensive strategy aimed at transforming the European Union into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy. It is a key document defining the strategy for action in the area of energy transformation for Europe [

42].

It is worth noting that, compared to previous strategic plans for reforming European Union society and economy (e.g., the Europe 2020 Strategy), energy transformation was included alongside competitiveness and growth as one of the main objectives (cf. [

43,

44]). The European Commission’s activities cover a wide range of sectors, including energy.

Table 5 provides detailed data on current initiatives and programmes.

The energy transformation process itself is shrouded in doubt and controversy for social and economic reasons. Many groups have raised questions about its purpose, as well as about the level of public awareness and acceptance, the state of public knowledge and education, and social readiness in the material sense, which seems to be rarely emphasised in discussions. The latter issue is rarely discussed, but it is important to emphasise that human potential, including the contribution of local actors and civil society (e.g., the European Union), is crucial throughout the transformation process. A thorough and accurate understanding of the complex relationships between the scientific, economic, political and social levels is essential for shaping effective political and economic strategies that will enable sustainable development and a high standard of living in a new, low-emission future [

48].

The author’s previous work has linked human capital with energy, introducing the concept of ‘homo energeticus’ [

49]. The research explains that energy levels change throughout life, as does the level of human capital (‘appreciation’ and ‘depreciation’), with consequences for individuals’ activity, as well as for individual regions and even entire economies from a macroeconomic perspective [

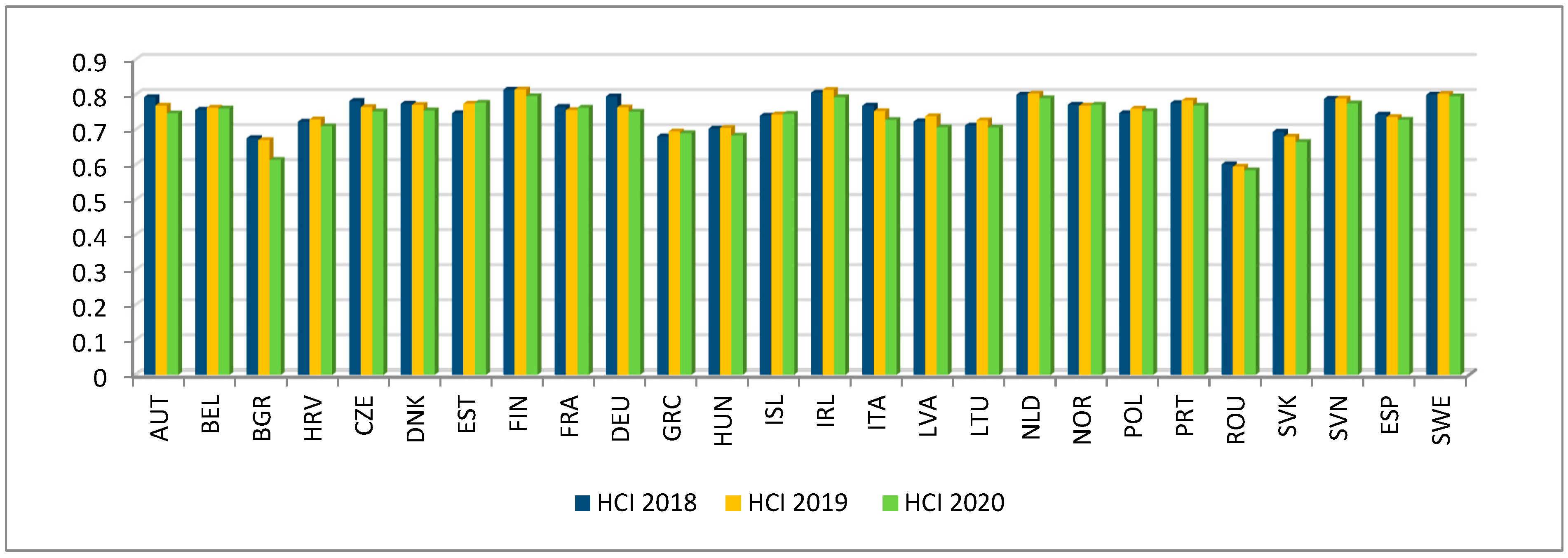

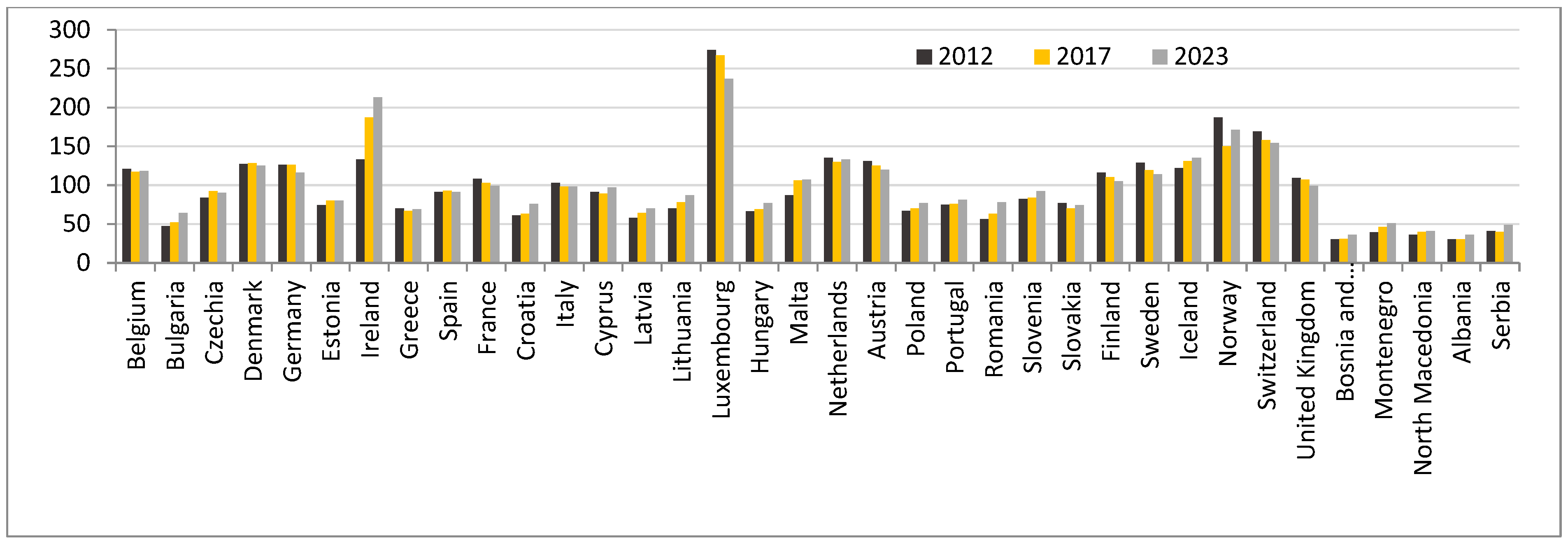

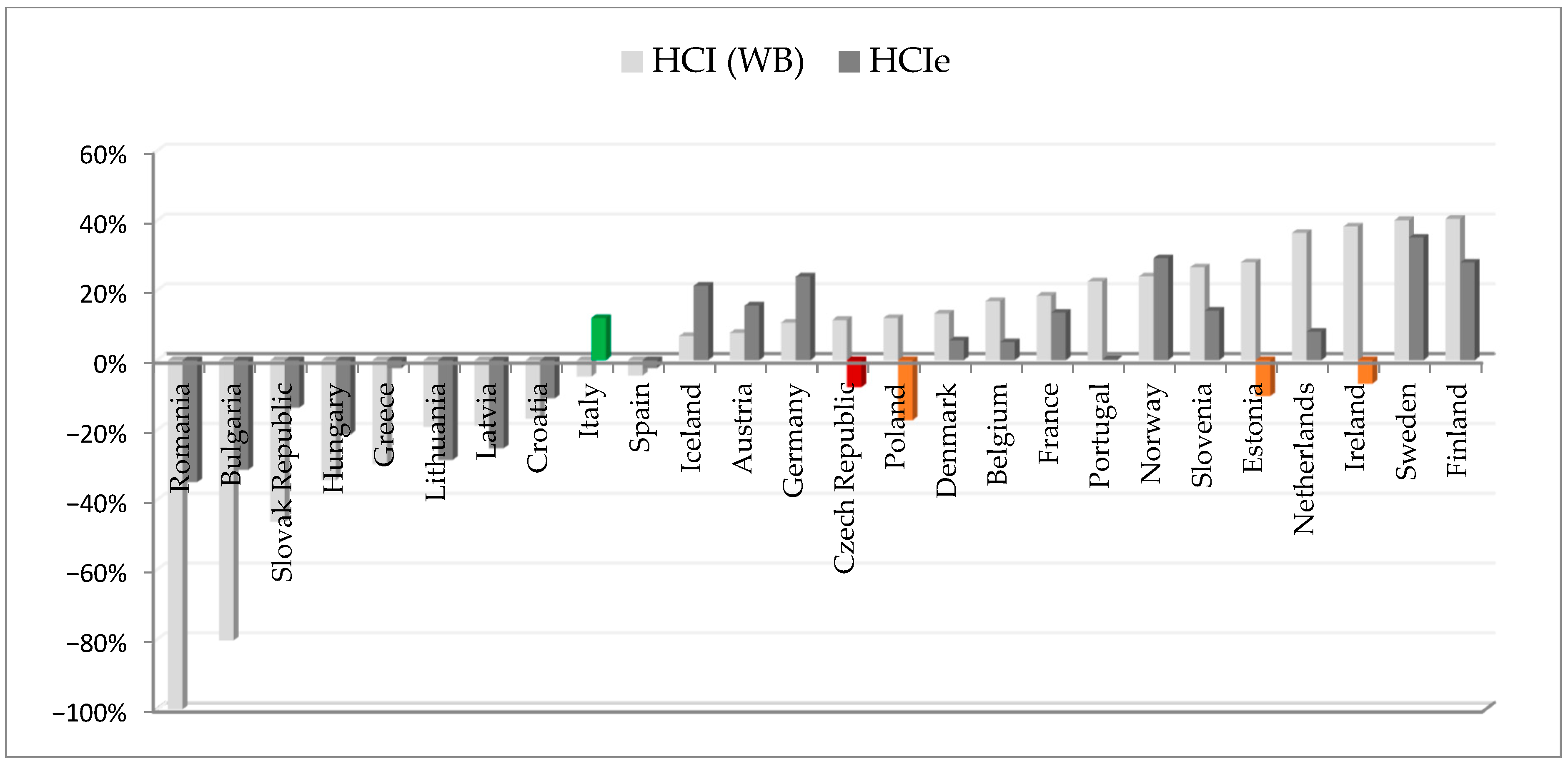

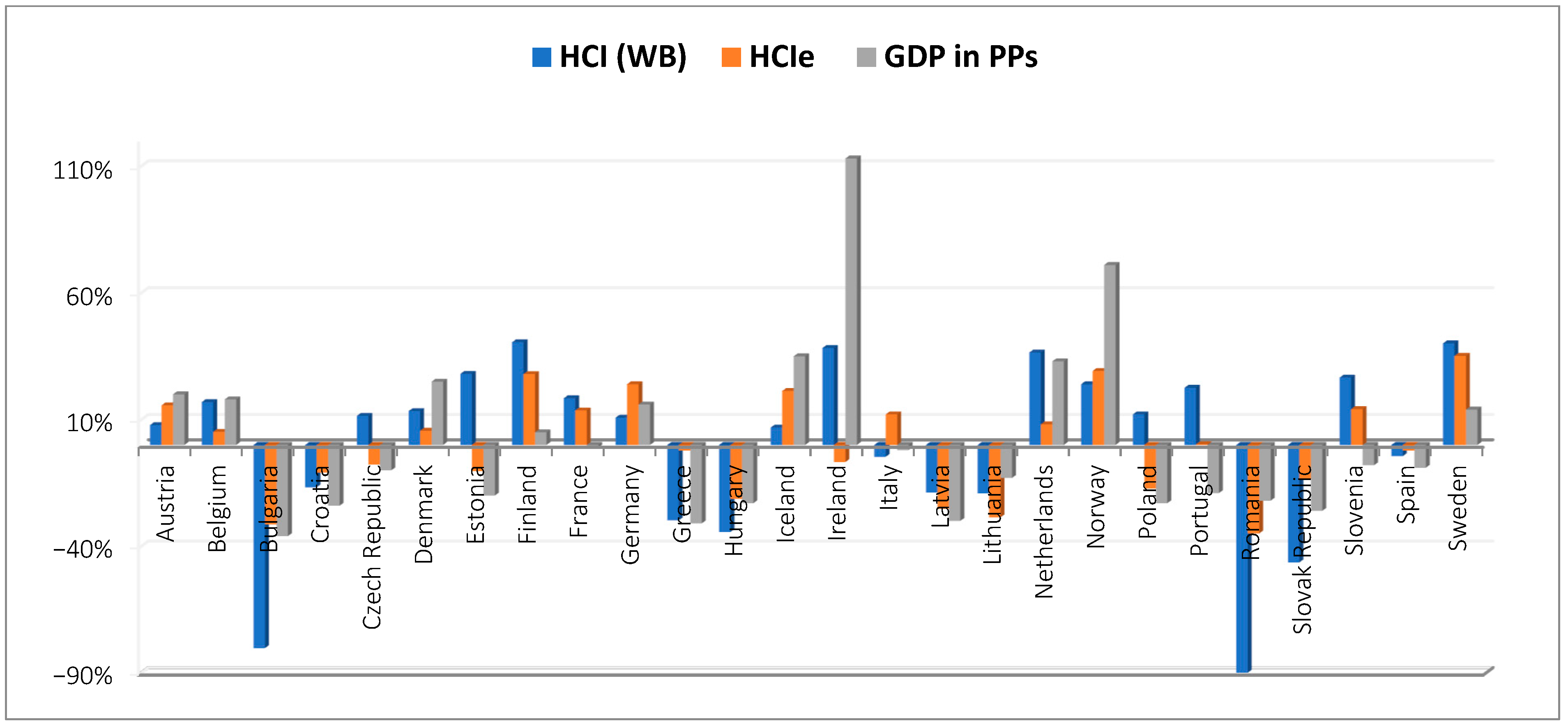

50]. This thesis is reflected in the latest data published by the World Bank, which estimates human capital levels using its own methodology. It transpires that, despite being considered highly developed, European countries exhibit significant variation in terms of this resource (see

Figure 1) and the wealth of their inhabitants (see

Figure 2).

2.4. Directions and Challenges in the Development of Human Capital in the Energy-Transforming Economy

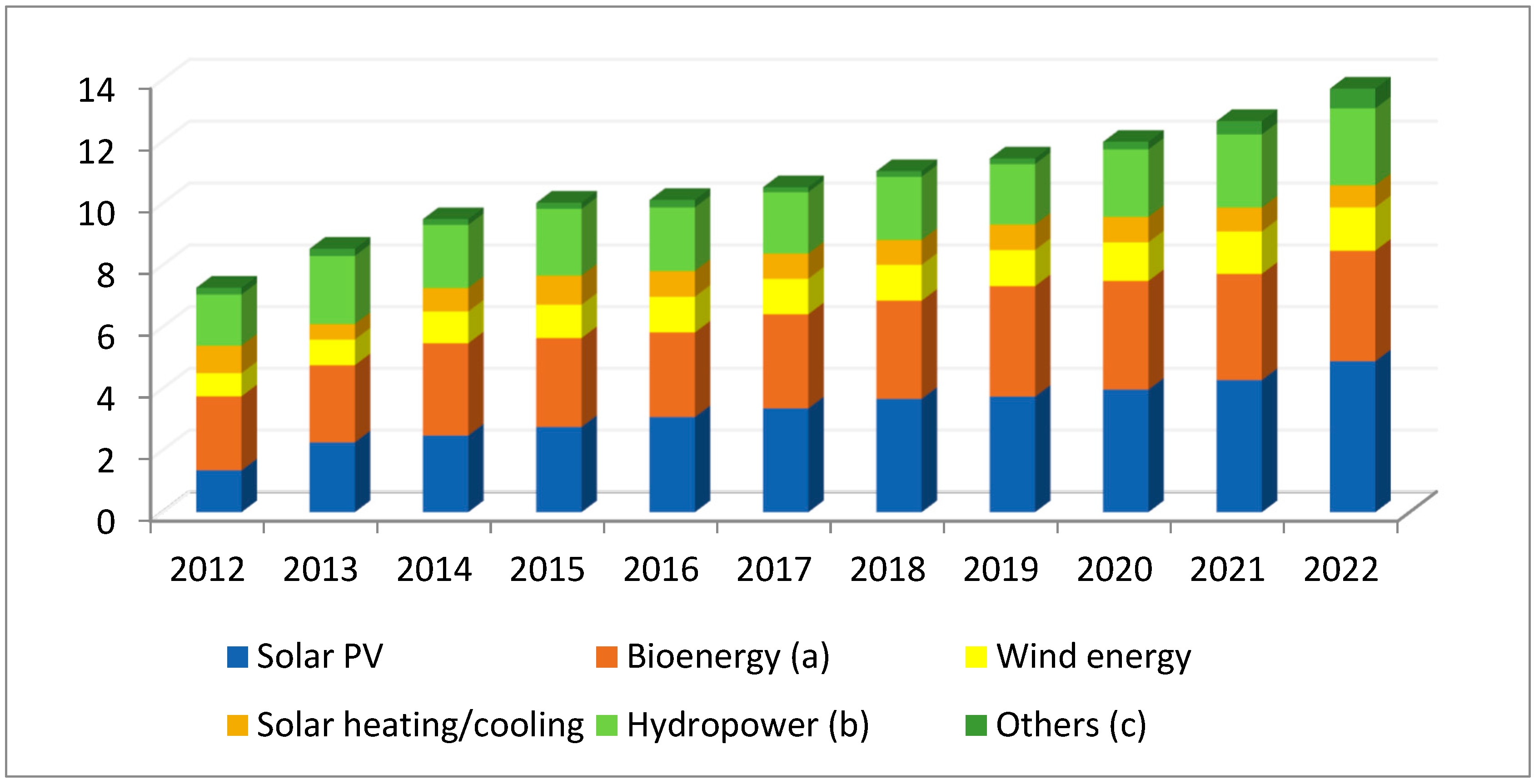

The renewable energy sector is a promising one worldwide, offering great potential for job creation. Investing in energy efficiency saves energy, reduces consumer bills and creates green jobs. According to the IRENA report [

51], the renewable energy sector recorded a record increase in employment in 2023, reaching 16.2 million jobs worldwide compared to 13.7 million in 2022. This indicates a strong growth trend that is likely to continue in 2025.

Figure 3 and

Table 6 present detailed data on the current level of employment. Furthermore, solar photovoltaics remained the largest employer in 2023, accounting for 7.2 million jobs. Significant numbers of jobs were also recorded in the liquid biofuels, hydropower, and wind energy sectors. The agency reports that 2024 saw a record increase in the installed capacity of renewable energy sources, which directly translates into job creation [

51]. Notably, China remains the leader in terms of the number of jobs in the renewable energy sector, followed by the European Union, Brazil, the United States, and India. However, according to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in autumn 2023, 62% of small and medium-sized energy sector enterprises had difficulty recruiting employees with the right skills [

52,

53].

The large-scale renewable energy skills partnership, launched in 2023, will help to deploy the renewable energy sources needed for the clean energy transition on a massive scale [

55]. According to the 2024 IRENA Report, the renewable energy sector in the EU is growing rapidly. In 2020, the sector employed around 1.3 million people, rising to 1.8 million three years later [

54]. However, to reach the 2030 target, it is estimated that 3.5 million jobs will be needed by 2030 [

51,

54]. Meanwhile, the EU construction sector employs almost 25 million people in around 5.3 million companies. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular benefit from the increased renovation market, as they account for 99% of EU construction companies and 90% of employment in the sector [

56]. Experts in the social aspects of climate change and just transition emphasise that necessary but worrying actions, such as closing coal mines in fossil fuel-based regions, can cause conflict in local communities. For this reason, it is believed that the transition should be carried out carefully, taking into account the social dimension of the problem. A key argument is that companies producing renewable energy could mitigate the effects of the energy and climate crises while creating around 500,000 new jobs by 2025. However, significant investment in human capital is required to improve employee qualifications. The European Commission argues that projects related to the energy transition (e.g., solar panels) could be financed by the Just Transition Fund, which would support European regions that rely on fossil fuels and high-emission industries in their green transition. One example of such a region is the Hornonitriansky region in Slovakia, which focuses mainly on producing black circles. Projects supported by the Just Transition Fund will receive investment, typically in small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as in research and innovation, renewable energy, emission reduction, the circular economy, and worker retraining.

Table 6.

Employment characteristics in the renewable energy sector by technology worldwide in 2022.

Table 6.

Employment characteristics in the renewable energy sector by technology worldwide in 2022.

| Technologies (Main) | Characteristics—Some Facts |

|---|

| Photovoltaics | Global solar PV employment reached 4.9 million in 2022, up from approximately 4.3 million the previous year.

Four of the ten leading countries are in Asia, two are in the Americas, and three are in Europe. Together, the top ten countries accounted for almost 4.1 million jobs, representing 85% of the global total. Asian countries accounted for 73% of the world’s PV jobs, reflecting the region’s continued dominance in manufacturing and installations. The remaining jobs were in the Americas (11.5%), Europe (11%, with EU member states accounting for 10.6%), and the rest of the world (4.8%).

PV employment in Europe was estimated at 540,000, 517,000 of which were in EU Member States.

Ten countries account for 85% of all jobs in the photovoltaic sector worldwide. China clearly dominates in terms of employment, accounting for around 56% of all jobs worldwide (approximately 2.7 million). Second place goes to India, the USA and Brazil. The third group comprises Japan, Vietnam and Poland. Germany, Spain and Australia make up the top 10. |

| Wind | In 2022, global employment in the onshore and offshore wind sector remained stable at 1.4 million jobs. However, employment in the wind sector was concentrated in a relatively small number of countries. China accounted for 48% of the global total alone, followed by Asia (55%), Europe (29%), the Americas (16%), and Africa and Oceania (0.7%). Together, the ten largest countries employed 1.23 million people (88%). Of these, four were in Europe (Germany, the UK, France and Spain), four were in Asia (China and India) and two were in the Americas (the USA and Brazil). The recent phenomenon of rising input costs has prompted OEMs to increase their efforts to outsource some of their component production to low-wage countries. This will change the geographic structure of the industry. |

| Hydropower | More than a third of all people employed directly in the sector worldwide worked in China (35.3%), while India and Brazil had significant shares of 18.8% and 7.8%, respectively.

Other countries with significant shares include Vietnam and Pakistan. Although smaller than the leaders, Vietnam (5.1%) and Pakistan (4.2%) also have significant shares in global hydropower employment.

The United States and Colombia have similar shares: The United States (2.7%) and Colombia (2.3%) have relatively similar shares, which are much smaller than those of the leading countries. Russia (1.9%), Ethiopia (1.8%), Turkey (1.6%) and Canada (1.4%) have even smaller shares.

Together, other countries account for 17.3% of global direct hydropower employment. This demonstrates that, while the leading countries have a significant presence, many other countries also contribute substantially to employment in the sector. |

| Liquid Biofuels | Worldwide biofuel employment reached 2.5 million in 2022, primarily in feedstock operations. There was a high concentration of employment, with the top ten countries accounting for 94% of global employment in the liquid biofuel sector. In cross-regional terms: Latin America accounted for 42% of all biofuel jobs worldwide and Asia (principally Southeast Asia) accounted for 37%. The more mechanised agricultural sectors of North America and Europe represent smaller employment shares (15% and 6%, respectively). Brazil clearly dominates the liquid biofuel sector in terms of employment, with around 0.8 million jobs. This represents 34% of all jobs in this sector worldwide. Indonesia ranks second with around 0.6 million jobs and the United States ranks third with around 0.35 million. Colombia and Thailand also have significant shares, with around 0.18 and 0.09 million jobs, respectively. The remaining countries—Malaysia, China, the Philippines, India and Poland—have a relatively small share of global employment in the liquid biofuels sector, with fewer than 0.1 million jobs each. |

Turning to the challenges that new socio-economic conditions pose to human capital, the first area is innovation and the development of modern technologies. Energy transformation relies on implementing new technologies in renewable energy sources (RES), energy storage, smart grids, energy efficiency and carbon capture. These innovative solutions require a high level of human capital, including educated engineers, scientists, researchers and programmers, to develop, improve and implement them. The second area of challenges relates to the growing demand for a qualified workforce. These qualifications mainly enable the construction, installation, operation and maintenance of new energy systems based on RES. All of these projects require the employees implementing them to have specialist knowledge and skills. The market is expected to provide experts in areas such as RES, energy storage, smart grids, energy efficiency, hydrogen technologies and carbon capture and storage (CCS), as well as digitalisation and the automation of energy systems. The energy transition is creating new jobs in sectors such as wind energy, photovoltaics and electromobility, as well as in areas related to the energy efficiency of buildings and industrial processes. A highly skilled workforce is essential to meet these new requirements. However, the energy transition will necessitate changes to the employment structure, particularly in sectors related to fossil fuels. Reskilling and upskilling programmes supported by appropriate investment in human capital will be essential for the fair and effective implementation of the transition. A high level of human capital, characterised by the ability to learn and adapt, will make it easier for employees to retrain and acquire the new skills required in the developing renewable energy sectors (RES).

Another important area is entrepreneurship and new business models, specifically the need to recruit managers who can understand and implement them. The energy transition is creating new business opportunities in areas such as renewable energy, energy services, smart grid technologies, and sustainable transport. Developing these new businesses and models will require entrepreneurs with competencies such as project management, communication, collaboration, problem solving, adaptability, entrepreneurship and innovation. These are key to coordinating complex transformation initiatives and engaging various stakeholders.

It should not be forgotten that a significant challenge in the process of energy transformation is obtaining broad public support and understanding of the benefits of switching to clean energy. A higher level of education and ecological awareness in society contributes to greater acceptance of changes in the energy system and supports the implementation of climate policies. School and even pre-school education (from a young age) should play an important role in this process. Properly prepared human capital will encourage greater citizen involvement in saving energy and using sustainable solutions. The success of the energy transformation process will also be evident in the effectiveness with which public policies are managed and implemented. A high level of human capital in the public sector is paramount, particularly at local level. Managing the energy transformation process requires competent, well-educated public administration specialists who can develop and implement coherent, effective energy and climate policies. At the local (rural) level, these individuals are often the primary point of contact for citizens and the key to transferring knowledge to society. This is a key condition for the transformation to proceed smoothly.

In summary, the complexity of the energy transition makes it necessary to adopt a new framework for expressing the essence of human capital. In this context, ‘Human Capital for an Economy in Energy Transition’ can be defined as the knowledge, technical skills (‘Green Skills’), behavioural attitudes and systemic adaptability required to achieve the goals of a sustainable energy transition. However, this human capital is distinguished from traditional technical green skills (e.g., the ability to install renewable energy panels) by the inclusion of aspects such as:

Systemic competencies: These encompass an understanding of technological, political and regulatory interconnections. They are a fundamental dimension of the Theory of Innovation Systems (TIS) because new technologies (e.g., hydrogen and energy storage) do not develop in isolation. They require skilled individuals (such as engineers, scientists and managers) who can manage knowledge flows, create networks and overcome institutional barriers [

10,

58]. Therefore, in a transforming economy, the role of human capital is to support (or hinder) the development of any technological innovation system.

Behavioural competencies: These represent the ability to manage change and the ethics of sustainable development. Energy transformation requires changes in social behaviour, as well as the attitudes of consumers and decision-makers. Technical knowledge alone is insufficient. In a transforming economy, human capital equips people with the ability to understand the environmental consequences of their actions and to incorporate pro-ecological norms, which, according to the Value-Belief-Norm Theory (VBT), leads to the acceptance or opposition of energy policies [

59]. This dimension appears to be essential for implementing the assumptions of an energy-transformation economy.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Objective and Research Area

The main empirical objectives are firstly to diagnose the overall level of human capital in the energy transition economy based on the original synthetic measure, HCIe, and secondly to analyse and assess the variation in its spatial distribution across the European socio-economic landscape, which serves as a foundation for developing a targeted policy typology directly linked to the identified cluster profiles and their specific weaknesses.

The general research question is: what is the level and extent of variation in the internal structure of human capital in the European socio-economic space? What actions should individual European countries take to support the development of human capital in the context of energy transformation?

The adopted research concept also poses two further questions: First, how can the essence of human capital be expressed in an energy-transforming economy? Second, are there appropriate measures for measuring it based on this research approach?

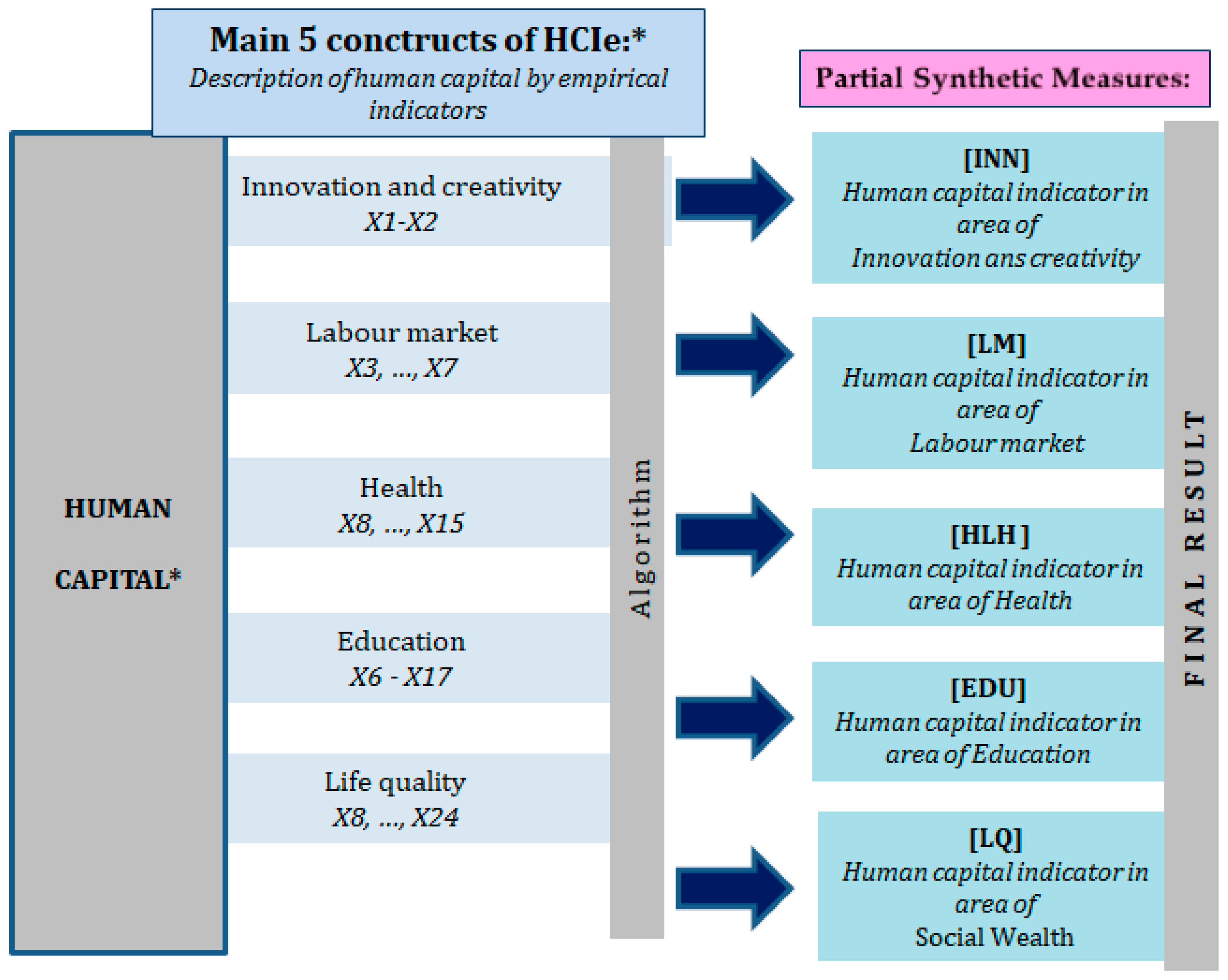

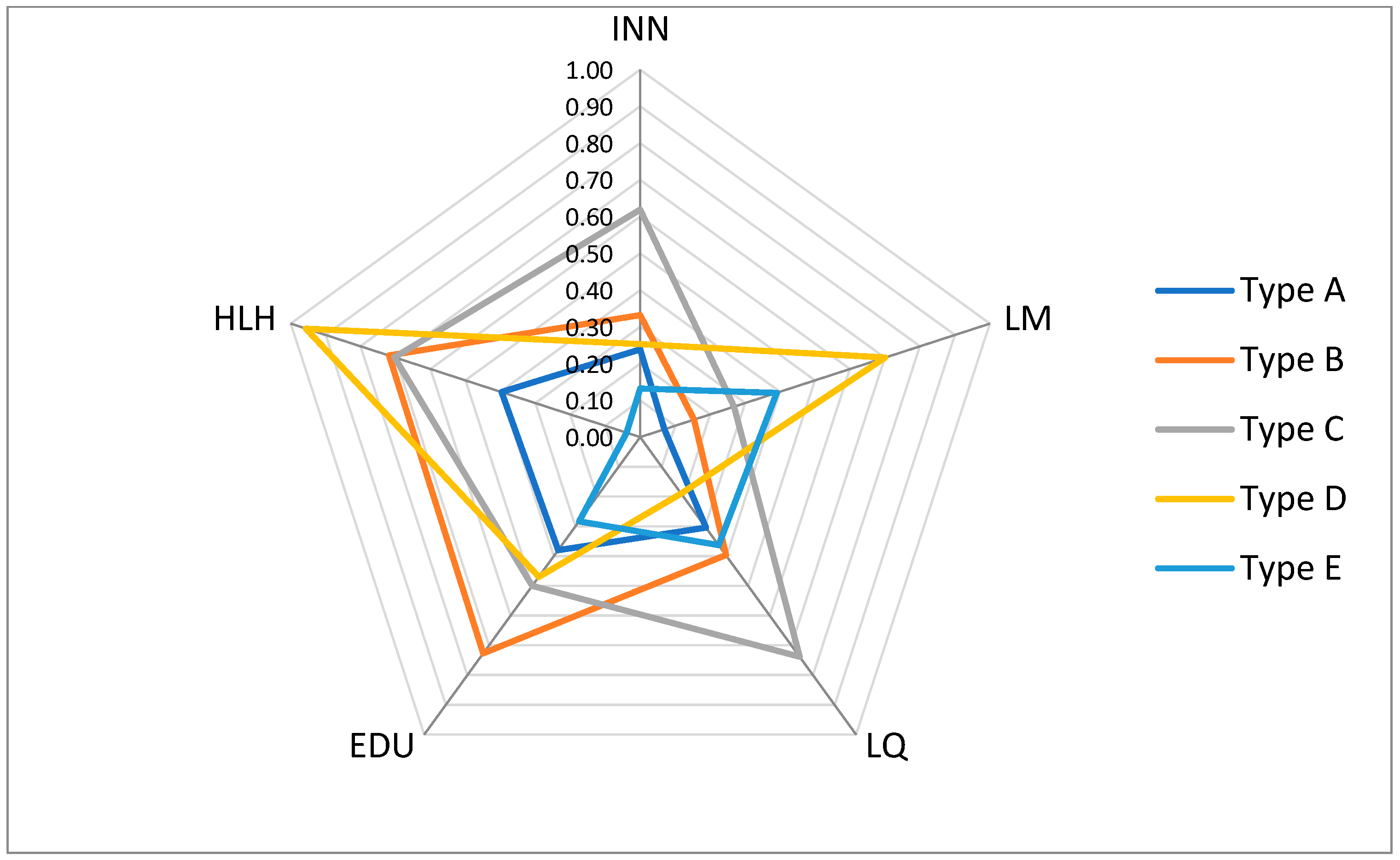

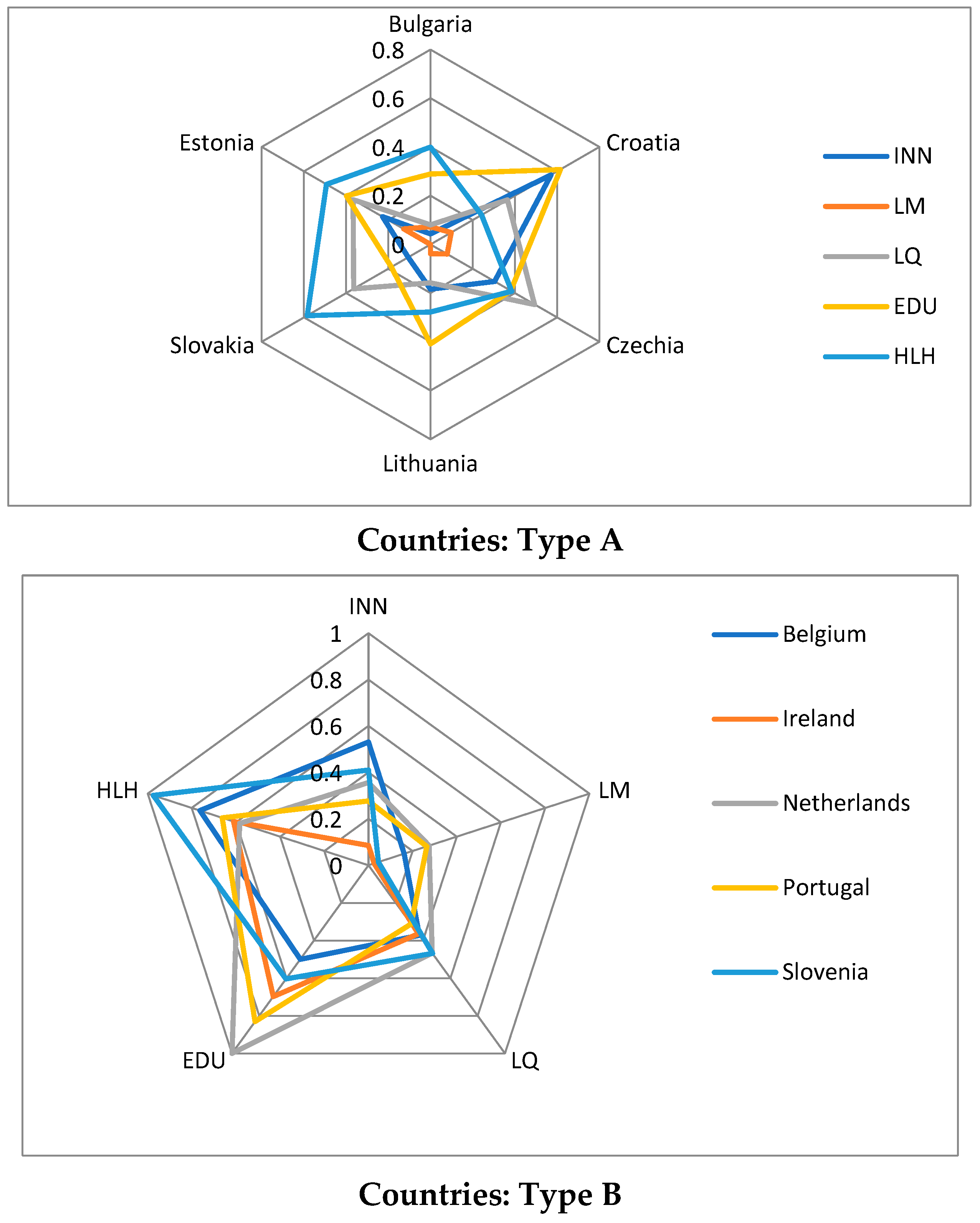

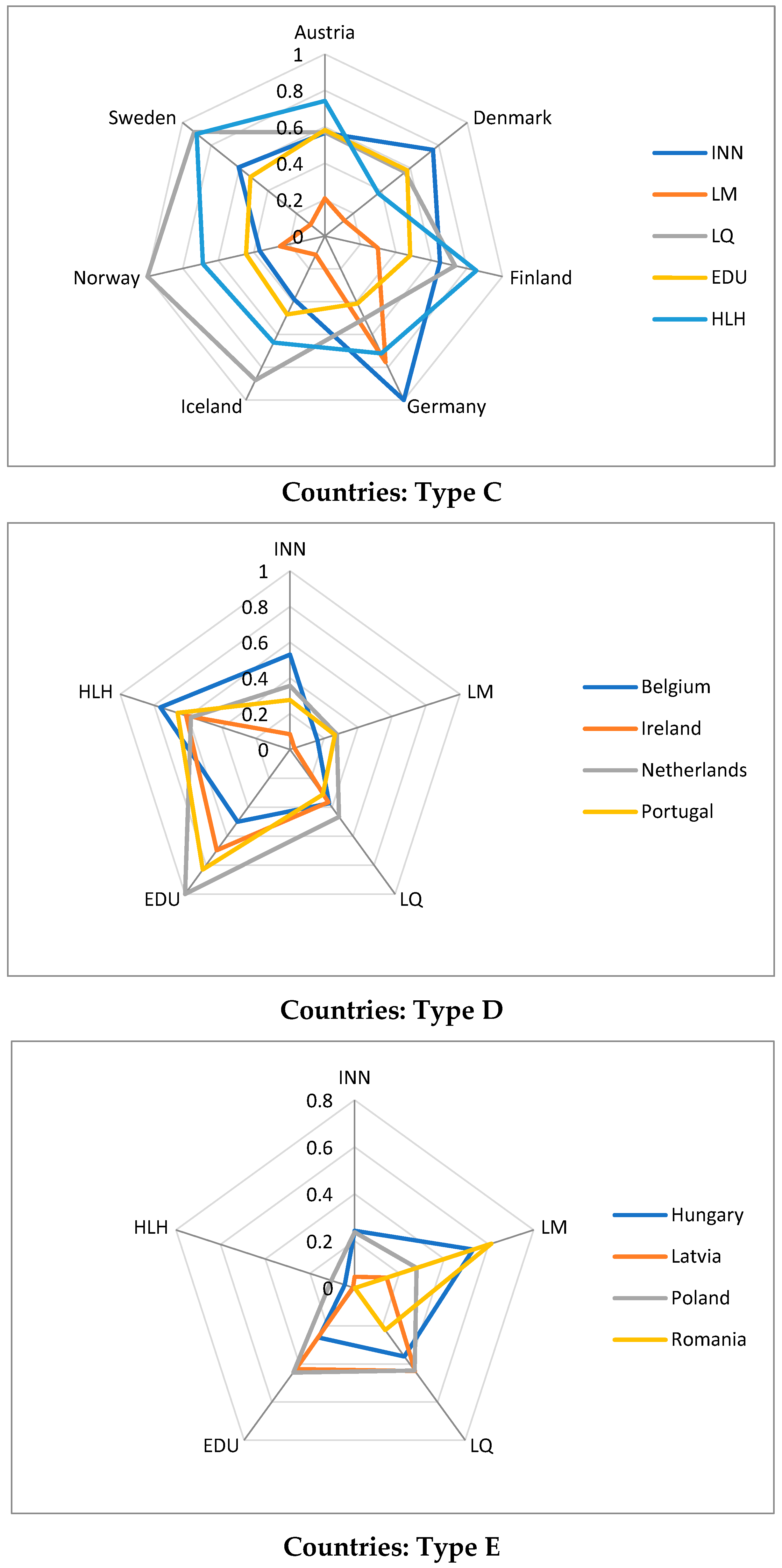

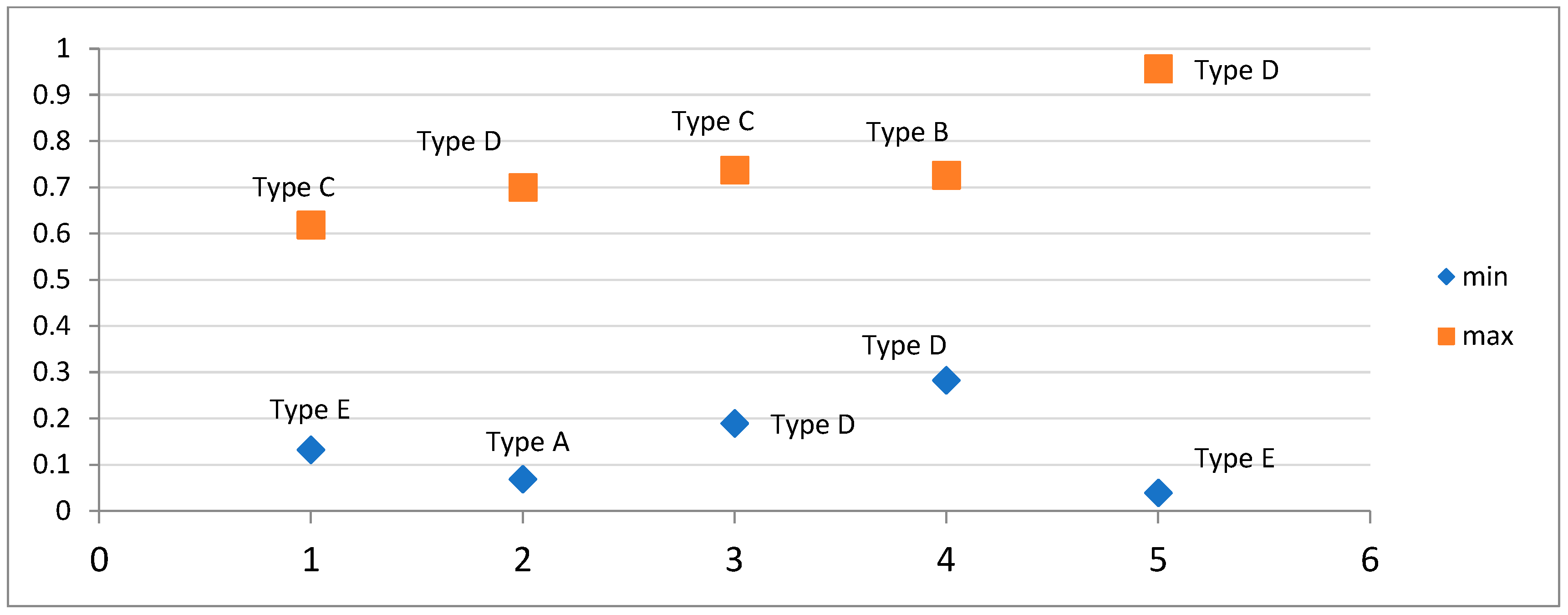

The empirical analysis focuses on the overall level of the human capital index (HCIe) in energy-transforming economies in European countries. Based on this index, a hierarchical classification of European countries has been developed. A detailed structural analysis of human capital was also conducted, including indicators—partial measures expressing the level of human capital for each of the five structural components: Innovation and Creativity (INN), Labour Market (LM), Health (HLH), Education (EDU) and Social Quality (LQ).

The final result of the research was the identification of similar groups of countries and their characteristics, as well as proposed scenarios dedicated to supporting the energy transition process for individual groups. Furthermore, based on the collected empirical material, an attempt was made to describe scenarios that would support the development of human capital in the different groups of countries, with the aim of optimising energy transition activities.

3.2. Research Sample: Criteria for Selecting Objects for the Study

The empirical analysis focused on European countries. The initial conceptual framework for this article had aimed to cover all European countries. However, this was not possible due to several limitations. The main selection criteria were data availability, completeness and continuity. The first limitation arose from the fact that the planned model data came from three different international databases: IRENA, EUROSTAT, OECD and the World Bank. However, it transpired that these data were not comparable due to the different countries for which these databases publish data. The second criterion for selecting the subjects was data completeness and continuity. Some countries did not meet this criterion (Montenegro, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, the United Kingdom, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Switzerland, Malta, and Cyprus). Ultimately, an analysis of the availability of data on empirical variables verified the original assumption and limited the study sample to 26 countries, eliminating those for which data were either unavailable or incomplete. The final study group comprised 24 EU member states and two non-EFTA countries: Norway and Iceland. It is important to note that twelve countries were excluded from the analysis due to a critical lack of data on key indicators, particularly those relating to the VBN (Behavioural Capital) and MLP (Institutional Governance) dimensions. It is fully recognised that this exclusion may affect the representativeness of regional findings, and therefore, great caution should be exercised when generalising the results of the study to the entire population.

3.3. The Definition of Human Capital in an Energy-Transforming Economy

The approach to constructing the human capital index used in this article directly refers to the classical approach to defining human capital and the basic components of its structure based on the methodological approach of Domański [

60] and Klonowska-Matynia [

61]. According to this approach, human capital is defined as the knowledge, skills, competencies, experience and health that individuals possess, which contribute to their productivity and economic growth. Investments in human capital, such as education and training, are considered a means of increasing the capacity of individuals and groups to generate economic value. An extension of this approach is “green” human capital, which considers the knowledge, skills, competencies, attitudes and commitment of individuals in relation to environmental protection and sustainable development. This includes the ability to innovate and implement green technologies, as well as the ecological awareness and skills necessary for functioning in a sustainable economy. In the context of energy transformation, human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, competencies, experience and health of individuals that are necessary for the effective design, implementation, management and maintenance of new, sustainable energy systems. This includes technical specialists, as well as people with non-technical skills who support the process.

3.4. The Operationalisation of the Concept of Human Capital in the Context of an Energy-Transforming Economy:Selection of Diagnostic Variables for the Model

Below, we propose a synthetic measure that expresses the overall level of human capital in an energy-intensive economy (HCIe). We also propose partial synthetic measures that express the level of this resource in a given component of its structure. We used the developed tool to diagnose and explore human capital in relation to the European socio-economic space.

Following the construction of the author’s human capital measure [

61] certain modifications were made to include features that express the essence of human capital in the classical approach while adapting it to an economy undergoing energy transformation. Five classic components of the HCIe indicator’s structure were adopted in its construction, as follows: Innovation and Creativity (INN), Labour Market (LM), Health (HLH), Education (EDU) and Social Quality (LQ). The set of diagnostic features was also modified to align with the adopted research concept. Twenty-four empirical variables (diagnostic variables) were introduced to the model. A detailed list is presented in

Table 7. It should be noted that the original set of data considered for inclusion in the model was much wider. Firstly, variables related to education published by the OECD were considered particularly useful and valuable. However, due to a lack of data for all countries and continuity issues, the final set of variables was limited to 24. All variables were analysed in the statistical procedure.

Table 7 provides a list of all diagnostic variables, along with their descriptions, sources, and time ranges. The data sources used to construct the HCIe measure and the individual partial measures were the EUROSTAT, OECD and IRENA databases. The IRENA database publishes a number of indicators relating to energy, with a particular focus on renewable energy. Furthermore, the subsequent empirical section of the article uses data on the World Bank’s Human Capital Index (HCI) and GDP from the EUROSTAT database to facilitate international comparisons.

The adopted set of diagnostic variables can contribute to discussions about their specificity in terms of causality and the effect they have on the level of human capital achieved. When studying complex categories such as human capital [

62], social capital or socioeconomic development [

63], the distinction between input and output, and therefore between cause and effect, becomes analytically blurred.

This issue is not only relevant to the classical theory of human capital [

6,

64]), but also forms a fundamental assumption of the Theory of Cumulative Causality in regional development. According to Myrdal’s [

65] approach, an initial advantage (high human capital) creates feedback loops whereby systemic outputs (e.g., a high level of TIS or VBN stability) become new inputs that enhance human capital. These phenomena are therefore endogenously linked. In this model, therefore, outcome and context indicators are treated not as simple effects, but as proxies for the functional effectiveness of human capital in the transformation system. This is fully consistent with the systems approach (TIS, MLP) and the issue of cumulative regional development.

A synthetic assessment of the correlations reveals that the Pearson correlation coefficients clearly indicate a strong positive correlation between investment in research and development, environmental sector development and renewable energy sources, and job creation. Furthermore, an increased share of renewable energy in final consumption and electricity production is negatively correlated with mortality from cancer, circulatory system diseases and respiratory diseases. This suggests that the transition to cleaner energy supports the economy and labour market and brings tangible health benefits to society by reducing air pollution. Indicators of ‘R&D expenditure’ show positive correlations with ‘job creation in the environmental economy’ and ‘job creation in the renewable energy sector’, suggesting that investment in research and development, as well as an increase in the number of researchers, contributes to job creation in green economy sectors. This is consistent with the expectation that innovations drive the development of new sectors. Mortality rates due to lifestyle diseases (cancer, circulatory and respiratory diseases) are strongly correlated with each other and negatively correlated with life expectancy. ‘Life expectancy at birth’ shows strong negative correlations with these mortality rates. Logically, the more people who die from these diseases, the shorter the average life expectancy. The same mortality rates also show negative correlations with the share of renewable energy and energy efficiency. This suggests that an increase in the share of renewable energy and improvements in energy efficiency tend to lead to a decrease in mortality due to these diseases. In general, the correlation coefficients are in line with expectations.

3.5. Construction of a Synthetic Measure of the General Level of Human Capital in the Energy Transformation Sector [HCIe], as Well as Partial Measures: Description of the Method

The [HCIe] measure was constructed based on the methodology of the original human capital [HCI] measure, which was developed for diagnosing rural areas in Poland [

61]. The universality of this measure enabled it to be adapted to the research concept adopted in this article. The study employed the taxonomic method of patternless hierarchy and classification of multi-feature objects, which is well-suited to the study of complex phenomena such as human capital [

61,

66,

67,

68]. The essence of human capital in each component of its structure was expressed by selecting diagnostic features (

x1, …,

xn) to create a matrix in the form

X= [

x(

ij)] [

68] as follow:

where

i—object (country);

j—diagnostic variable.

Each object was characterised by a vector of diagnostic variables in the following form:

After initial statistical verification in terms of correlations and the coefficient of variation (V > 0.1), the empirical variables (so-called diagnostic features) were subjected to normalisation using the zero unitarisation method (MUZ) according to the formula [

66].

where

i—index of the calculated partial indicator, takes values from 1 to n [n number of partial indicators).

j—index of a given country. takes values from 1 to 26 [number of countries).

xij—specific value of i-th factor achieved by j-th country in a given year.

min{xij}—minimum value of i-th factor. achieved by countries in a given year.

max{xij}—maximum value of i-th factor. achieved by countries in a given year.

After adding up the previously normalised values, the values of the destimulants were transformed by multiplying them by −1. Having at hand the matrices of the optimal variable values normalized in any way, determined in the first step of the two-stage information capacity method, in the next step, the partial variables were aggregated according to the formula:

As a result of dividing the value of

qi by the number of diagnostic variables n, synthetic variables

Qi were obtained in the

i-th object, expressing the assessment of each of the examined objects (countries) in terms of the general level of human capital in the area of the energy transformation of the HCIe economy, contained in the range [0;1]. A characteristic feature of the obtained synthetic measure is the ordering of the complex phenomenon using a single value, allowing for comparative analyses to be carried out in such a way that the interpretation of the obtained hierarchy is facilitated without changing the order of objects [

68]. These units were then grouped into classes based on similar levels of human capital. The range of the

Qi variable was then used to classify the objects.:

The classification of spatial units involves the complete and disjoint division of a given heterogeneous set of objects (in this case, countries) into a number of non-empty subsets that are more homogeneous internally. Based on this established range, five classes of objects of an equal size were determined. Applying the above procedure resulted in a hierarchical classification of municipalities according to their human capital index (HCI). The classification of spatial units was performed ex post [por. [

63,

69,

70,

71,

72]]. The analysis of empirical data resulted in the identification of classes that optimally reflected the observed similarities and differences between the analysed spatial units (

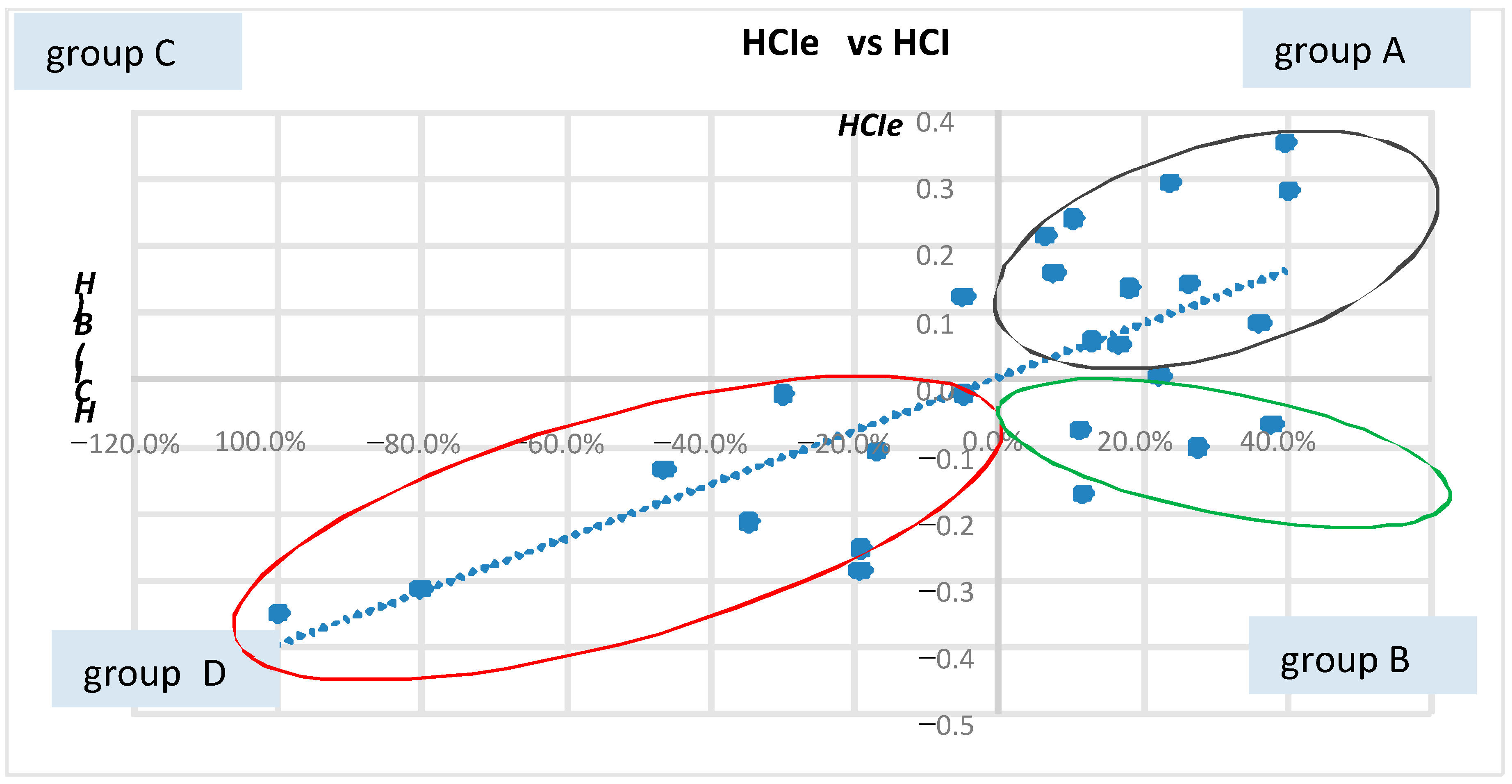

Figure 4).

The above procedure was also used to estimate the level of human capital for each structural component (component) separately. Innovation and Creativity (INN), Health (HLH), Education (E), Labour Market (LM) and Quality of Life (LQ) (

Figure 5).

A key methodological challenge was establishing the weights for the individual structural components of the HCIe index, a task that is inherently problematic and controversial when constructing synthetic measures. This study used an equal weighting approach for all five synthetic components. This approach was adopted to maintain methodological neutrality and avoid arbitrariness in the underlying approach. Often recommended for constructing composite indicators in the absence of expert consensus on relative weighting [

73] this methodology ensures that the final HCIe result is not biased towards any one component.

When estimating the main measure (HCIe) and the individual partial measures (INN, LM, HLH, EDU and LQ), it was assumed that all diagnostic variables were equivalent. No additional weights were introduced for the individual empirical variables or partial components. Many authors emphasise that the issue of assigning weights in the construction of synthetic measures is controversial. In this case, given the lack of similar research on human capital in the energy transformation economy and the potential for referencing expert knowledge, it was deemed challenging to maintain relative objectivity when assigning weights to individual empirical variables.

Furthermore, the following criteria were maintained when constructing synthetic measures for the model: data continuity, completeness, comparability and reliability. The empirical data were verified using statistical tests. The strength and direction of the interdependencies between the variables included in the overall HCI measure were examined, as were the relationships between the structural components of human capital (partial measures). Correlation analysis confirmed the presence of positive levels of interdependency between the adopted components, albeit varied. The observed strength and direction of these interdependencies are valid and do not duplicate the same information.

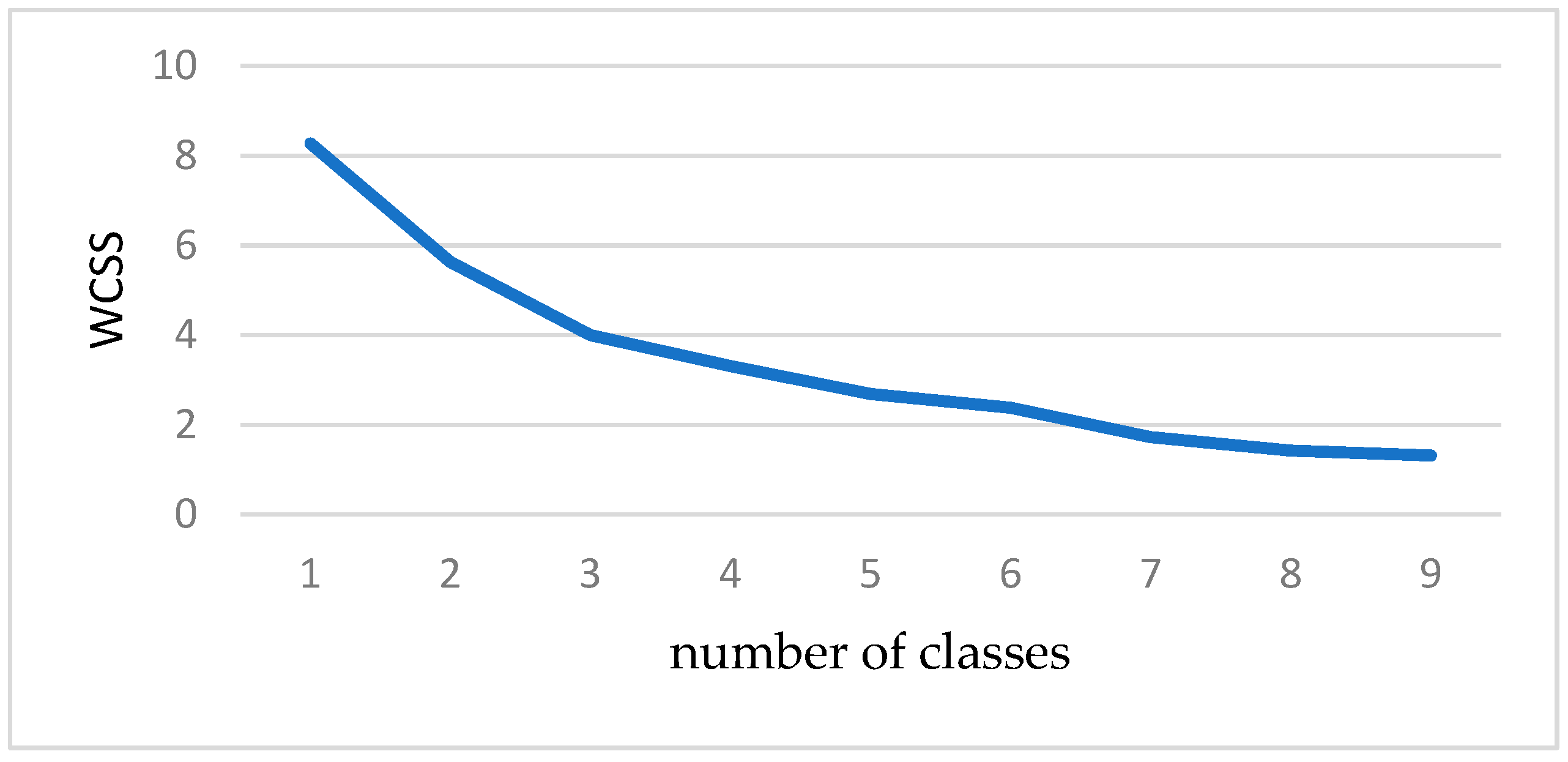

A multivariate analysis method, namely cluster analysis based on the k-means algorithm, was used to explore European countries in terms of their human capital structure for the energy transition economy. The k-means method is a non-hierarchical algorithm that involves searching for and isolating groups of similar objects (clusters). Calculations were performed using the Statistica 13.0 software package.

The k-means method was used to create k different clusters of countries, each as distinct as possible from the others, while optimising variability within and between clusters. Clearly, the similarity within each cluster should be as high as possible, while the clusters themselves should be as distinct from each other as possible. The advantage of this method is that it allows us to examine both the distribution of components and the relationships between them. It is possible to determine the strengths and weaknesses of individual components and identify the presence or absence of certain factors (features). The specific nature of the typology allows it to be used to describe many aspects of socio-economic space, such as the labour market, demographic structure, social and economic fabric, and other characteristics.

The cognitive specificity of each typological analysis is determined by the research objective and data availability. Furthermore, despite the use of statistical methods and the implementation of formally binding research procedures, each typology, including the author’s own, is conventional in nature.

The first step of the k-means algorithm involves assigning each object (country) to the nearest centroid (cluster centre). This is achieved by minimising the distance of each object from the nearest centroid. In the standard implementation, the algorithm uses the squared Euclidean distance, which eliminates the need for the square root and thus simplifies the calculations while minimising the time taken by the algorithm (while maintaining the same proximity order).

The optimisation criterion (WCSS) that the algorithm tries to minimise is the sum of the squared Euclidean distances between points and their centroids, i.e., the Intra-Cluster Distance Sum of Squares (WCSS). In this study, the optimal number of clusters (k) was determined in a stepwise manner by testing different values of k and ensuring consistency with domain knowledge. This means that the clusters created for the selected k were meaningful in the context of the discussed problem and provided a satisfactory basis for interpreting the results. The results obtained were enhanced by using the Elbow statistical test, which determines the optimal number of clusters while minimising total variability within clusters based on the following formula [

74]:

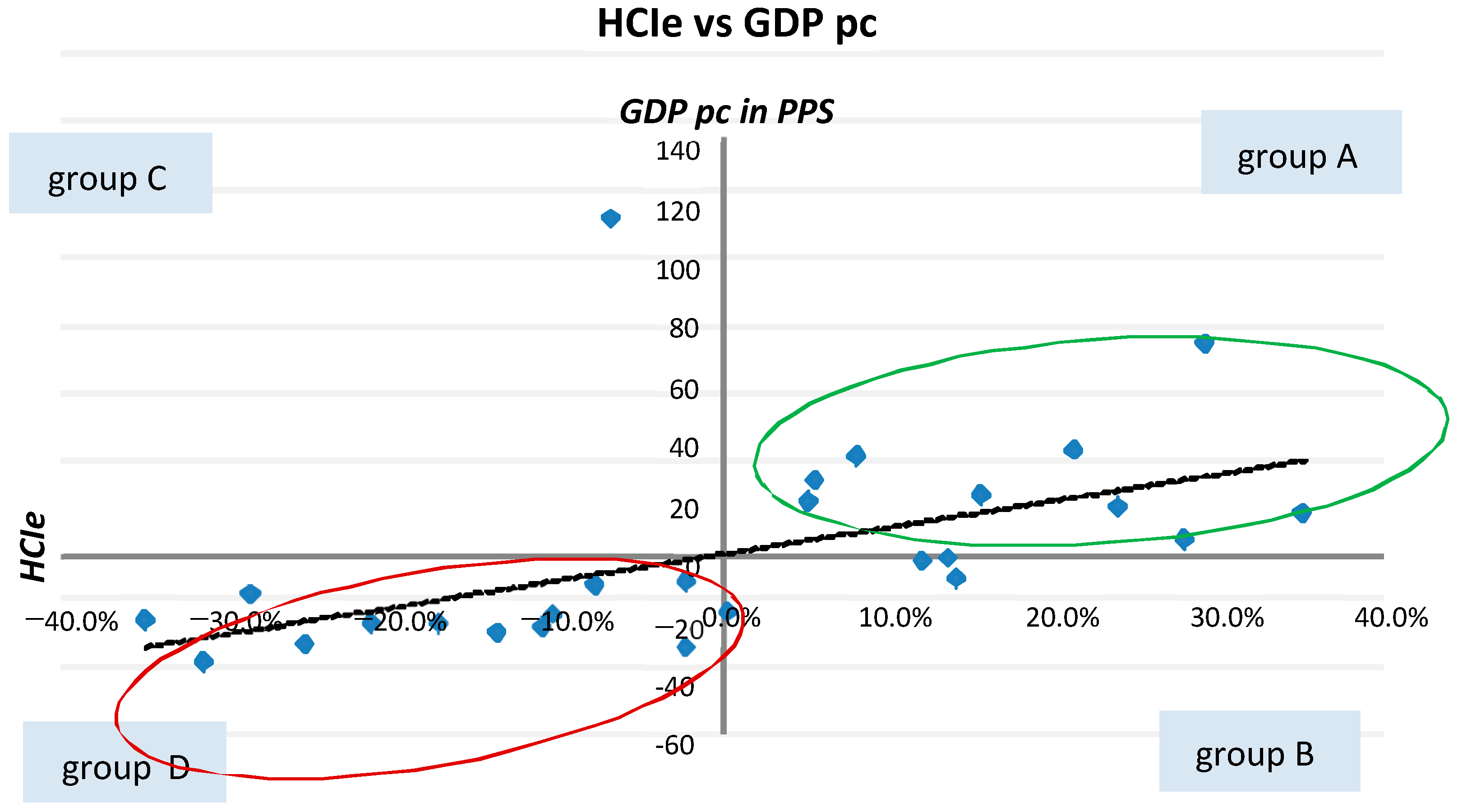

The two methods used—hierarchical classification and non-hierarchical grouping—provide different information. The HCIe measure enables the level of resources to be determined. In this case, it may be found that different countries have similar HCIe levels, but this does not mean that they achieved them based on the same internal potential. As the adopted concept explores the structure of human capital in five areas—the so-called structural components—only the non-hierarchical grouping method reveals surpluses or deficits in a given area that characterise a given country. For this reason, using these two methods seems justified.

3.6. Justification for Selecting the Variables for the Model

Selecting diagnostic variables for constructing synthetic measures is always controversial. This case is no exception, with the absence of wider studies posing a significant barrier. Nevertheless, this article attempts to create a measure that expresses the overall level of human capital in HCI and the level of human capital in each of its components separately. The primary criterion for selecting the diagnostic variables for the model was the existing scientific literature on the role of human capital in socio-economic development processes. Furthermore, the author’s research and publication experience in this area presented challenges. Collecting data that would capture the essence of human capital for an economy undergoing energy transformation was problematic. Due to the limited number of publications in this area, some variables were arbitrarily selected for the model based on the author’s personal judgement and the available research results from other authors across various scientific disciplines. A descriptive justification for selecting the most sensitive, controversial and problematic variables is provided below. This justification is presented sequentially for each component of the human capital structure, as assumed in the model for the HCIe indicator.

3.6.1. Component: Innovation and Creativity (INN)

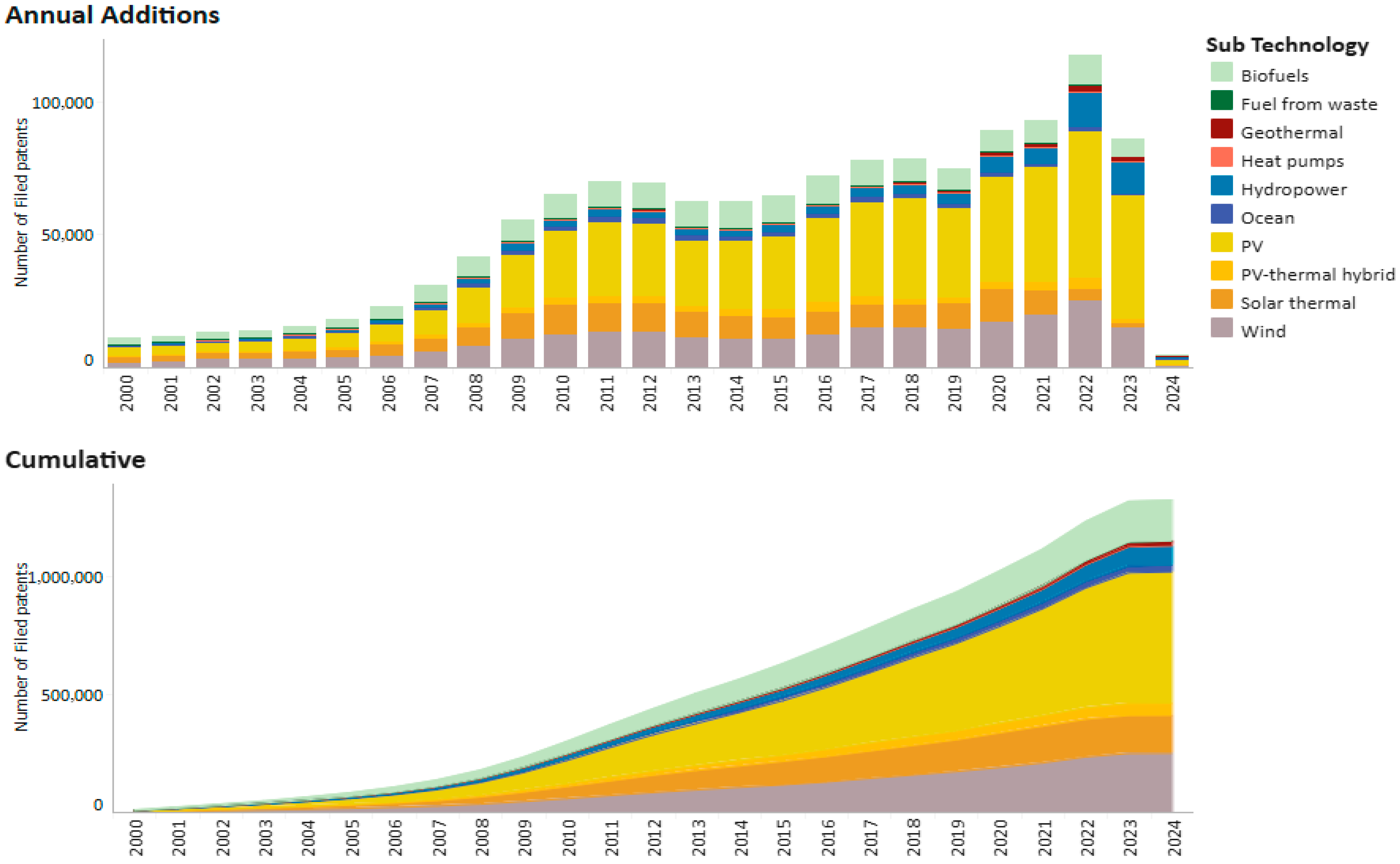

Based on previous experience of measuring human capital in an economy undergoing energy transformation, the classic variable of expenditure on research and development was used to capture the essence of this component. Additionally, to adapt the classic measure to an economy undergoing energy transformation, the number of renewable energy patents was used as a variable. According to data published by IRENA in Renewable Energy Patents Evolution [

75] the number of patents worldwide is increasing, with solar energy (PV) accounting for the largest share.

Figure 6 below presents data on patents worldwide in recent years, including all technologies and subtechnologies.

To compare European countries in terms of their level of innovation, data on renewable energy patents per 100,000 inhabitants over the last three years was used (see

Figure 7).

In general, three countries stood out as leaders in innovation during the analysed period: Germany, Croatia and Denmark. The countries with the fewest patents per 100,000 inhabitants (i.e., less than two) are: Ireland, Latvia, Greece, Bulgaria and Belgium. Examining the diversity of technologies used in renewable energy patents, it was observed that, since 2018, most patents filed are essentially related to the area of ‘adaptation’, i.e., modifying and adapting existing patented technologies to improve them, expand their applications, or circumvent existing rights. This is a key element of continuous development and innovation in the clean energy sector. Some changes have been observed since 2021, with the exceptions to the observed trend being: Iceland (power and geothermal energy), Ireland (power and ocean energy in 2021 and wind energy in 2022), Estonia (wind energy in 2022 and building and enabling technologies in 2021) and Poland (building and solar energy PV in 2022) [

76].

3.6.2. Component: Health [HLH]

The next component of the human capital structure was the ‘Health’ component. This component was modified and new empirical variables were introduced to express the essence of this resource in the context of an energy transformation economy. Health is now considered one of the forms of human capital [

6,

77,

78]. Good health is a fundamental prerequisite for human life and social well-being [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. This section focuses on justifying the variables adopted in the ‘Health’ area in the context of the energy transformation economy.

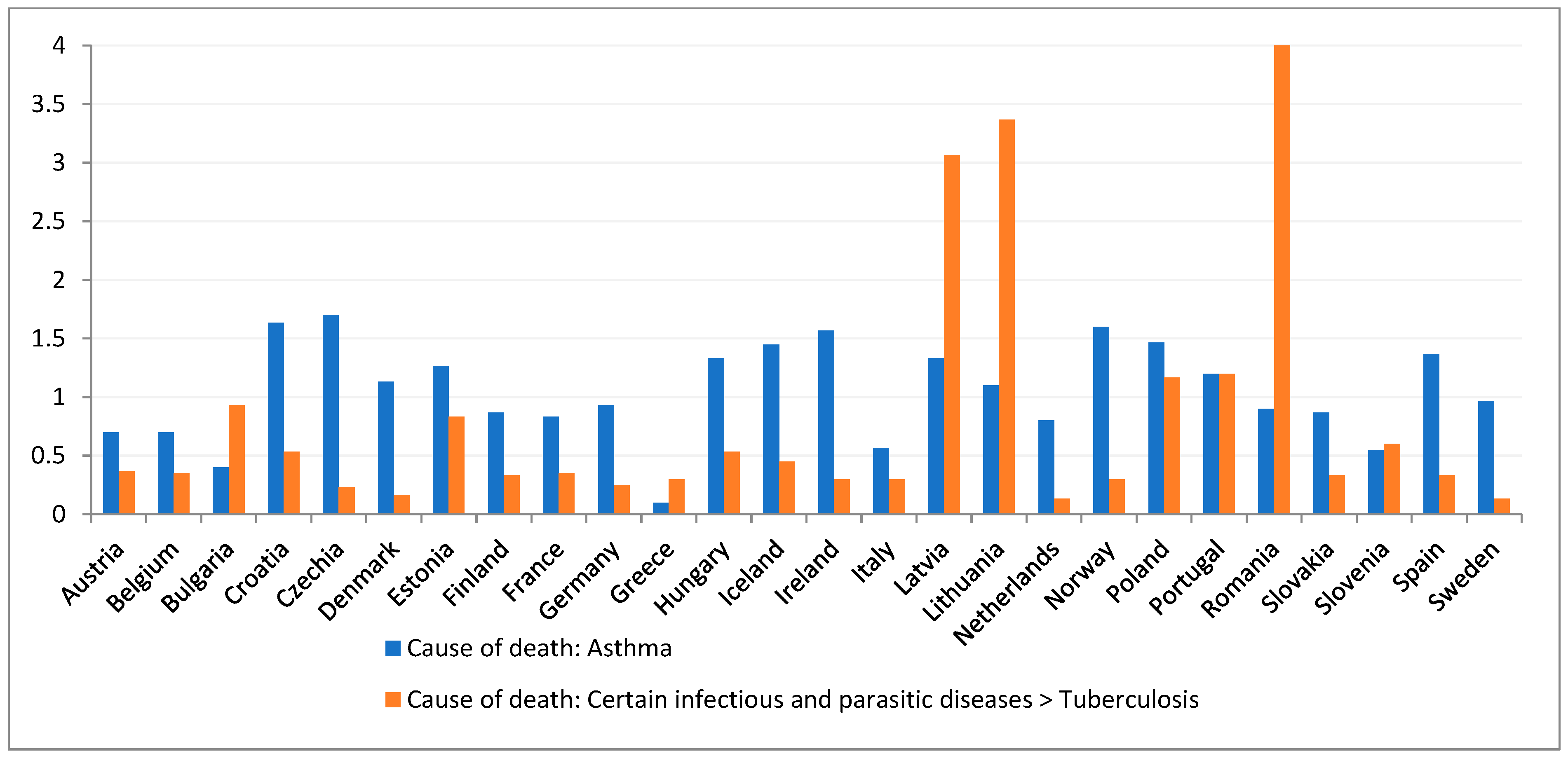

The HCIe index in the ‘Health’ area comprises seven variables, five of which are directly related to causes of death. Analysing these causes of death reveals potential links with energy policy, although these are not direct and require further analysis and context. Nevertheless, there are several arguments that justify the selection of these variables and suggest that energy policy may impact the listed causes of death. The impact of energy policy on respiratory diseases can be assessed on the basis of pollutant emissions, for example. The main source of air pollution is the combustion of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) in power plants, heating systems and transport. Gaseous air pollutants include carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur oxides, nitrogen oxides, ammonia and ground-level ozone. Particulate matter includes dust, soil, acids, organic molecules and some metals. Long-term exposure to these pollutants significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, heart attacks and strokes [

84], as well as respiratory diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumonia and lung cancer [

85]. Exposure is also associated with adverse birth outcomes and obesity [

86]. In 2019, outdoor air pollution in urban and rural areas was estimated to cause 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide each year. Additionally, certain industrial processes in the energy sector (e.g., fuel extraction and processing) can expose workers and local communities to carcinogens. There is growing evidence that widespread environmental contaminants known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can have an adverse effect on the reproductive health of animals and humans, and are associated with infertility [

87,

88], as well as ageing and female reproductive diseases [

89,

90]. Energy policies that promote renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, electromobility, and cleaner combustion technologies can reduce emissions of these pollutants and thus improve air quality, reducing morbidity and mortality due to respiratory diseases [

86,

91]. As indicated by data on mortality from selected causes in European countries, there is huge variation in scale (see

Figure 8).

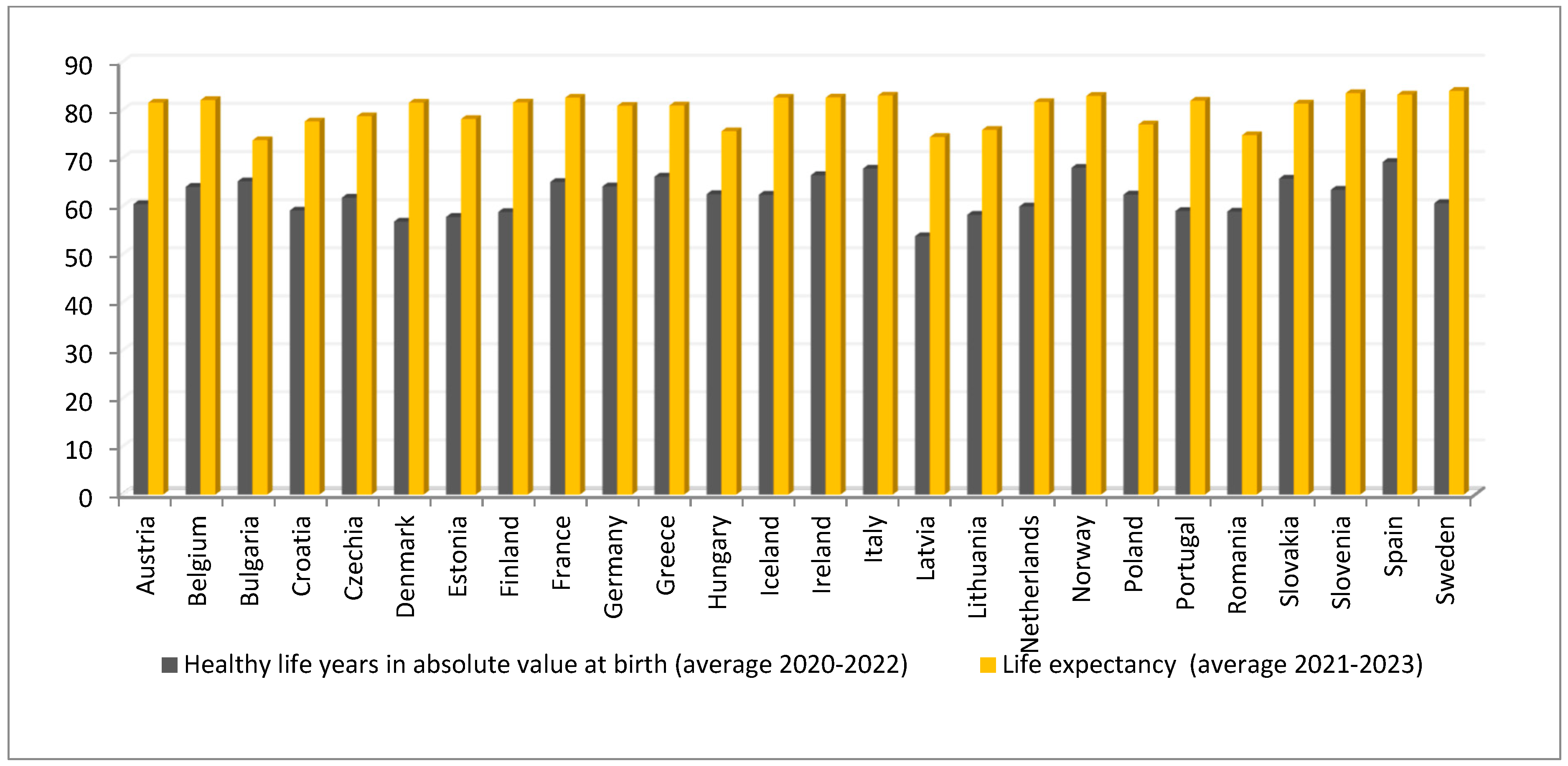

In addition to the causes of death, two further indicators were used to illustrate human capital: healthy life years at birth and life expectancy. These data are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. The average life expectancy in the group of 26 European countries is 80.1 years. The longest life expectancy is found in the northern countries (more than 83 years): Sweden (83.9 years), Slovenia, Spain, Norway and Iceland. The shortest life expectancy (approximately 74 years) is found among the inhabitants of Bulgaria, Romania and Latvia. On average, people live in good health for 62.2 years. The shortest average was observed in Latvia at 53.8 years, while in southern European countries such as Spain and Greece, it is the longest at over 69 years.

Zandel et al. [

92] have also implicated neurological and mental disorders, albeit less directly, in energy policy. Air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter, is increasingly associated with adverse neurological and mental health outcomes, especially in children and the elderly. It may ultimately contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases and poor mental health. There is growing evidence that exposure to air pollution affects the central nervous system [

93,

94,

95], with studies showing adverse effects on cognitive and behavioural functioning, attention, intelligence quotient (IQ), memory and academic performance [

96,

97,

98]. Recent studies have also shown that air pollution is a major risk factor for internalising psychopathology. For instance, a recent meta-analysis revealed a strong association between elevated levels of airborne particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) and an increased risk of anxiety, depression, and suicide, as well as changes in brain regions linked to psychopathological risk [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103].

Anxiety and depression are the most common mental health conditions worldwide [

104] and can increase the risk of suicide attempts and completion [

105]. They can also have an adverse effect on family and social relationships and are associated with a significant economic burden for individuals and society. Indeed, these disorders cost the global economy approximately US

$1 trillion per year in lost productivity [

106]. Given that 99% of the world’s population lives in environments that do not meet World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for air quality [

107], understanding the potential role of air pollution in the risk of mental illness is a major public health concern. Furthermore, more than one in ten people worldwide lived with a mental health disorder in 2019 [

104]. In addition to the above-listed diseases, endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases are also associated with energy policy, albeit indirectly. Some air pollutants have been found to have endocrine-active effects, which can potentially affect the hormonal system and increase the risk of metabolic diseases [

108]. Furthermore, energy policy can influence the availability and cost of food through its impact on agriculture and transport, which may be significant for nutritional and metabolic diseases [

107]. Promoting sustainable energy production and transport can have a positive indirect impact on these areas of health [

106]. Switching to cleaner energy sources and implementing stricter regulations on industrial emissions could reduce exposure to these risk factors.

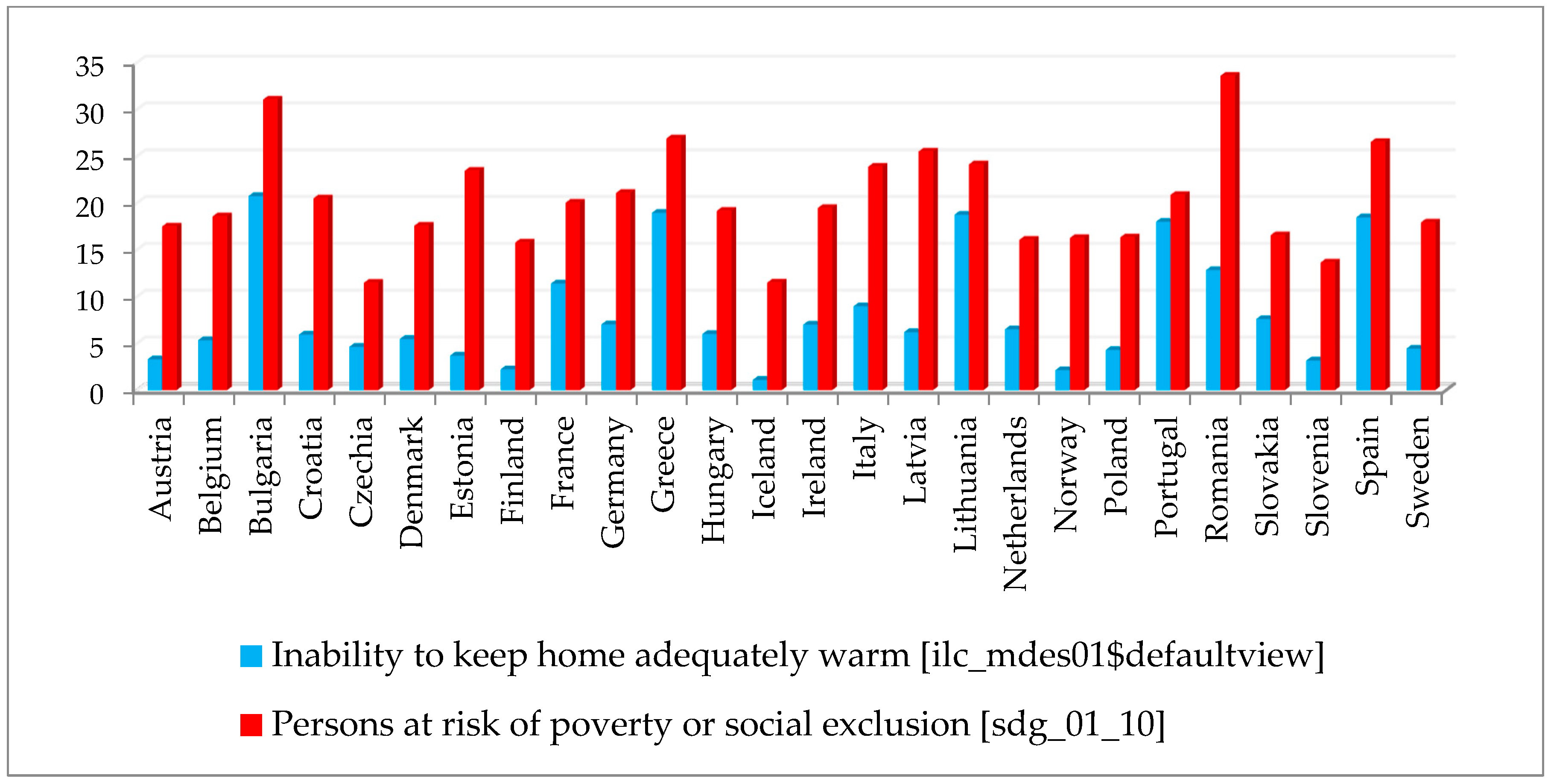

3.6.3. Component: Quality of Life (LQ)

A classic and widely used measure of human capital in the area of quality of life is GDP per capita, but it could also be the number of people living in poverty or the long-term unemployment rate. However, the focus of this study was on variables that would explain quality of life in the context of an economy undergoing energy transformation (see

Table 7). The question of the social aspects of a just energy transformation is particularly important in this context. Does the transition to renewable energy sources and the decarbonisation of the economy have the potential to reduce or increase energy poverty? How can energy policy contribute to reducing the negative health effects associated with an inability to heat a home? How can programmes to improve the energy efficiency of buildings reduce demand and lower bills for poor households? In this context, one of the variables included in the expression of the essence of human capital was the indicator ‘Inability to keep home adequately warm’, which refers to energy poverty. This measures the percentage of the population or households that cannot afford to heat their homes to an adequate temperature for health and comfort. A high value of this indicator suggests that a significant proportion of society is struggling to meet their basic energy needs for heating. This highlights a social and economic problem.

According to the Energy Poverty Observatory [

109], energy poverty is defined as a lack of access to basic energy services by households and individuals. This phenomenon has many consequences, affecting health [

110,

111], life satisfaction [

112,

113] and the environment [

114]. It can also indirectly reflect the quality of housing, since poorly insulated properties require more energy to heat efficiently, thereby increasing the risk of energy poverty. In Central and Eastern Europe, district heating plays a significant role in providing heat to households. The material and social characteristics of district heating mean it can both prevent and cause energy poverty. Households in Central and Eastern Europe are often ‘trapped’ in unsatisfactory or unprofitable heating systems with limited options for change [

115,

116].

The energy transition required to achieve decarbonisation goals is expected to radically alter the technologies and energy sources used in our economies, as well as how we consume energy. This could have significant impacts on low-income, vulnerable consumers, who may be unable to make the necessary investments or fuel changes, or who may suffer from higher prices. Some studies show that households with lower incomes, smaller sizes or lower levels of education are disproportionately affected by energy poverty during transitions to cleaner energy sources, such as electricity and gas [

117]. Other studies highlight that, under these policies, households affected by energy poverty may have difficulty accessing basic energy services, which could deepen social inequalities. With the implementation of the EU CO

2 Emissions Trading System in 2027, transport costs could increase by almost one third, affecting the prices of goods and services and exacerbating energy poverty [

118,

119,

120].

Figure 11 presents data on the scale of energy and social poverty. It should be noted that these are not identical phenomena. A high level of the ‘inability to keep home adequately warm’ indicator suggests a risk of growing social inequalities and primarily affects the poorest European countries (Romania and Bulgaria) as well as southern countries such as Greece, Spain and Portugal, and some Eastern European countries (Lithuania). The scale of social poverty is much higher and less diverse than that of energy poverty in all European countries. Even in highly developed and wealthy countries such as Sweden, a significant proportion of the population is at risk of social poverty. Despite theoretical cost advantages over fossil and nuclear energy sources, renewable energy deployment is currently associated with higher income needs and increased risk of energy poverty, mainly because commercial producers retain the economic surplus from renewable energy. At the same time, consumers are burdened with subsidies. For example, the renewable energy tax in Germany has disproportionately burdened households affected by energy poverty [

121]. In summary, energy poverty, or the inability of a household to afford basic energy services, is an expression of a fundamental socio-political injustice with serious detrimental effects on equality, health and well-being [

122] (On 1 July 2022, the EEG fee (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz—Renewable Energy Sources Act) in Germany was completely abolished, which was intended to provide relief to consumers in the face of rising energy costs.).

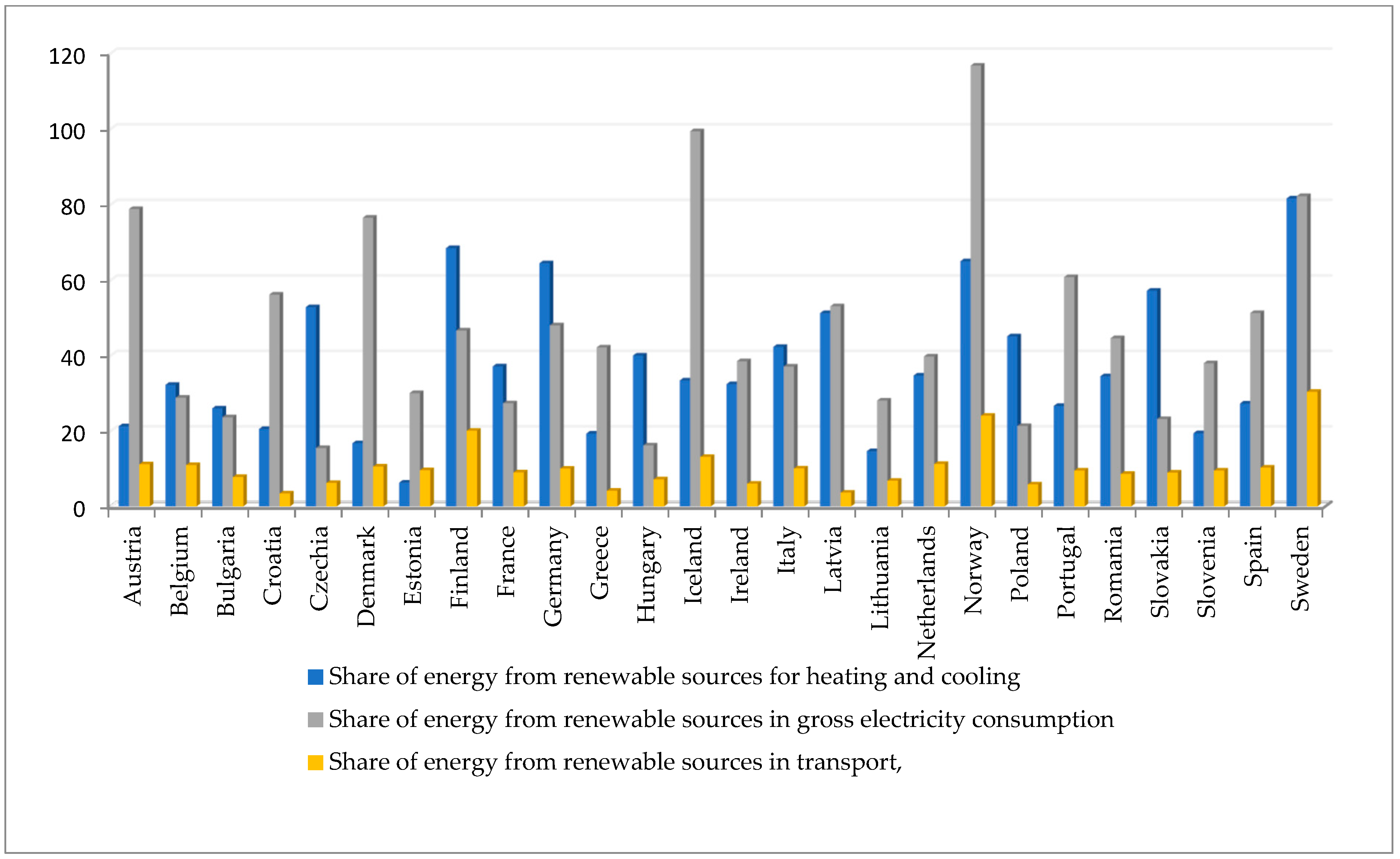

Another indicator used in the empirical analysis of the “Quality of life” area is the “Overall share of energy from renewable sources”, which is closely linked to human capital in the transformation to a zero-emission economy (

Figure 12). The first is the quality of public health, which was described in detail in an earlier section of the article. The literature indicates that energy transformation has a positive impact on public health by reducing air pollution. Studies such as the global analysis of cardiovascular diseases by Lelieveld et al. [

123] emphasise the negative effects of pollution from the combustion of fossil fuels. The Lancet Countdown systematically documents the health benefits of switching to cleaner energy sources [

124]. Raunio and Karjalainen’s [

125] analysis of Nordic countries provides evidence of the positive local health effects of reducing energy-related emissions. Together, these publications argue that an energy transition leads to improved population health and increased productivity, as well as reduced healthcare costs, thereby enhancing human potential.

Another aspect of the quality of life in an economy undergoing energy transformation is the mitigation of climate change and the promotion of well-being. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s extensive reports provide compelling scientific evidence of the key role of renewable energy sources [

126]. The Stern economic analysis (2007) argues that investments in clean energy, including renewable energy sources, are economically justified in the long term [

127]. These investments contribute to the protection of natural resources and a stable environment, both of which are essential for the sustainable well-being and development of future generations. It is impossible to talk about quality of life without considering social development itself. Reports in the International Energy Agency’s “Energy Access Outlook” [

128] series emphasise the role of decentralised renewable energy solutions in providing access to energy for remote and underdeveloped communities. This has a direct impact on improving living conditions and enabling the development of human potential [

128]. Bhattacharyya’s (2019) review examines the links between access to energy, often based on renewable energy sources in rural areas, and social development and poverty reduction [

129].

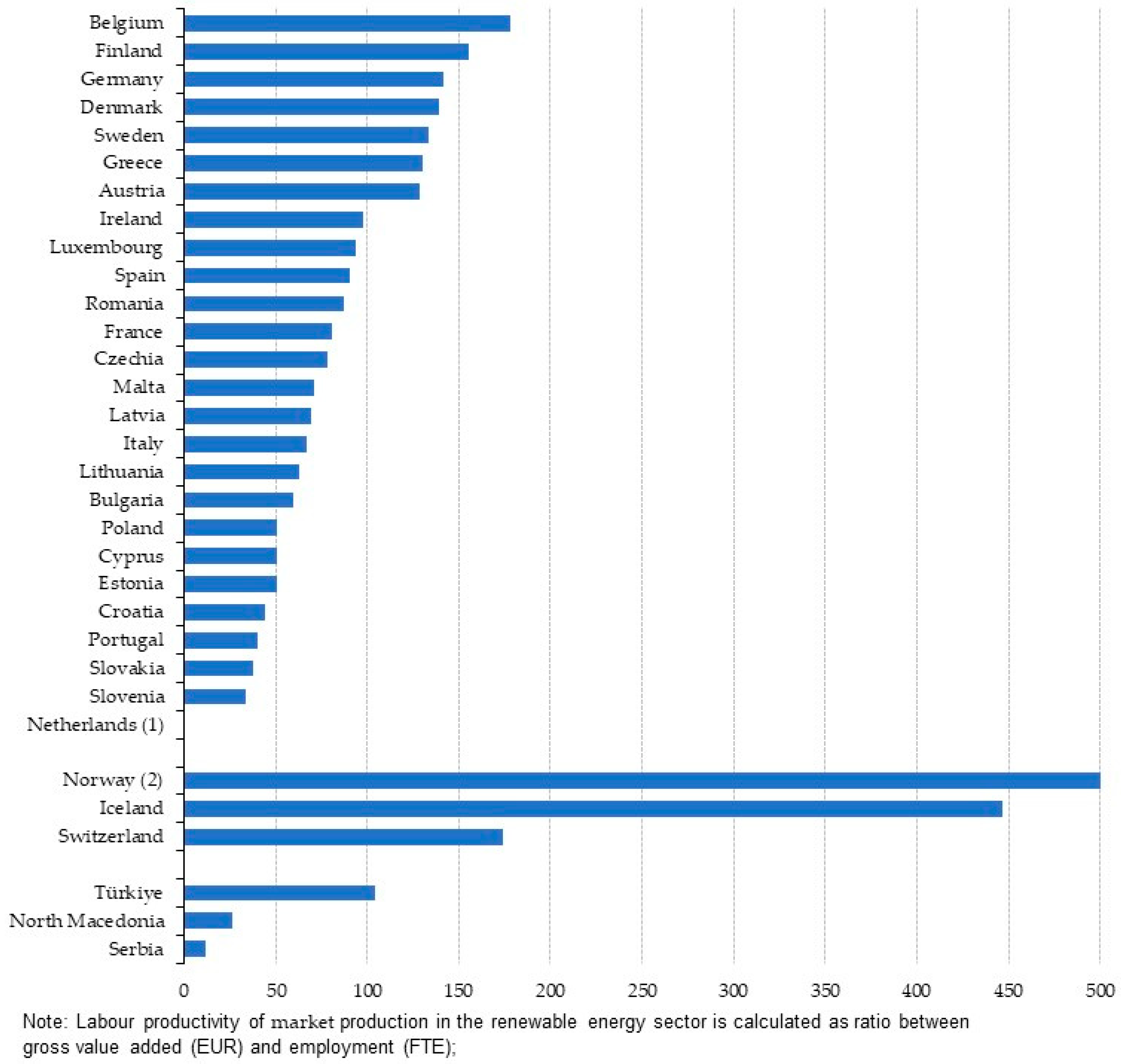

3.6.4. Component: Labour Market (LM)

Quality of life is undoubtedly related to health and well-being, but it also affects the labour market and employment. From an individual’s perspective, economic security and a decent standard of living thanks to employment are essential for a good life. In macroeconomic terms, increasing the share of renewable energy sources requires suitably qualified staff to operate, develop and manage this new energy system and related sectors of the economy (‘green’ skills). Studies analyse how investments in clean energy, including RES, affect job creation and economic growth potential. Reports by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), such as the annual Renewable Energy and Jobs—Annual Review, provide global data confirming the creation of new jobs in the renewable energy sector. Pollin, Heintz and Garrett-Peltier’s (2009) study analyses the potential for economic growth and job creation through clean energy investments. These publications indicate that energy transformation is necessary not only from an environmental point of view, but also creates new economic and professional opportunities, thereby improving quality of life and strengthening human capital [

130].

According to reports by [

54] investments in renewable energy create jobs in the production, installation, operation and maintenance of equipment, while energy efficiency programmes for buildings, transport and industry generate employment opportunities in areas such as energy audits, modernisation and the production of energy-efficient technologies. A number of actions can ensure that the transition to a clean energy future is job-rich and fair. To demonstrate the role of human capital in the labour market of a transforming economy, the study uses data on ‘Labour productivity of market production in the renewable energy sector’, among others. This indicator measures the efficiency with which labour is used to produce goods and services in the renewable energy sector (see

Figure 13). High labour productivity means that the sector is more competitive and generates more added value per employee. This allows for comparison of labour productivity in the renewable energy sector with labour productivity in other energy sectors (e.g., the fossil fuel sector) or in the entire economy. An increase in labour productivity in the renewable energy sector may indicate technological progress and innovation, enabling the production of more energy with fewer workers. Changes in labour productivity can affect employment in the renewable energy sector. Increases in productivity could lead to more energy being produced with fewer workers, but they could also stimulate growth in the sector and job creation in other areas (e.g., research and development, equipment manufacturing).