Optimization of Start-Extraction Time for Coalbed Methane Well in Mining Area Using Fluid–Solid Coupling Numerical Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Modeling and Simulation Schemes

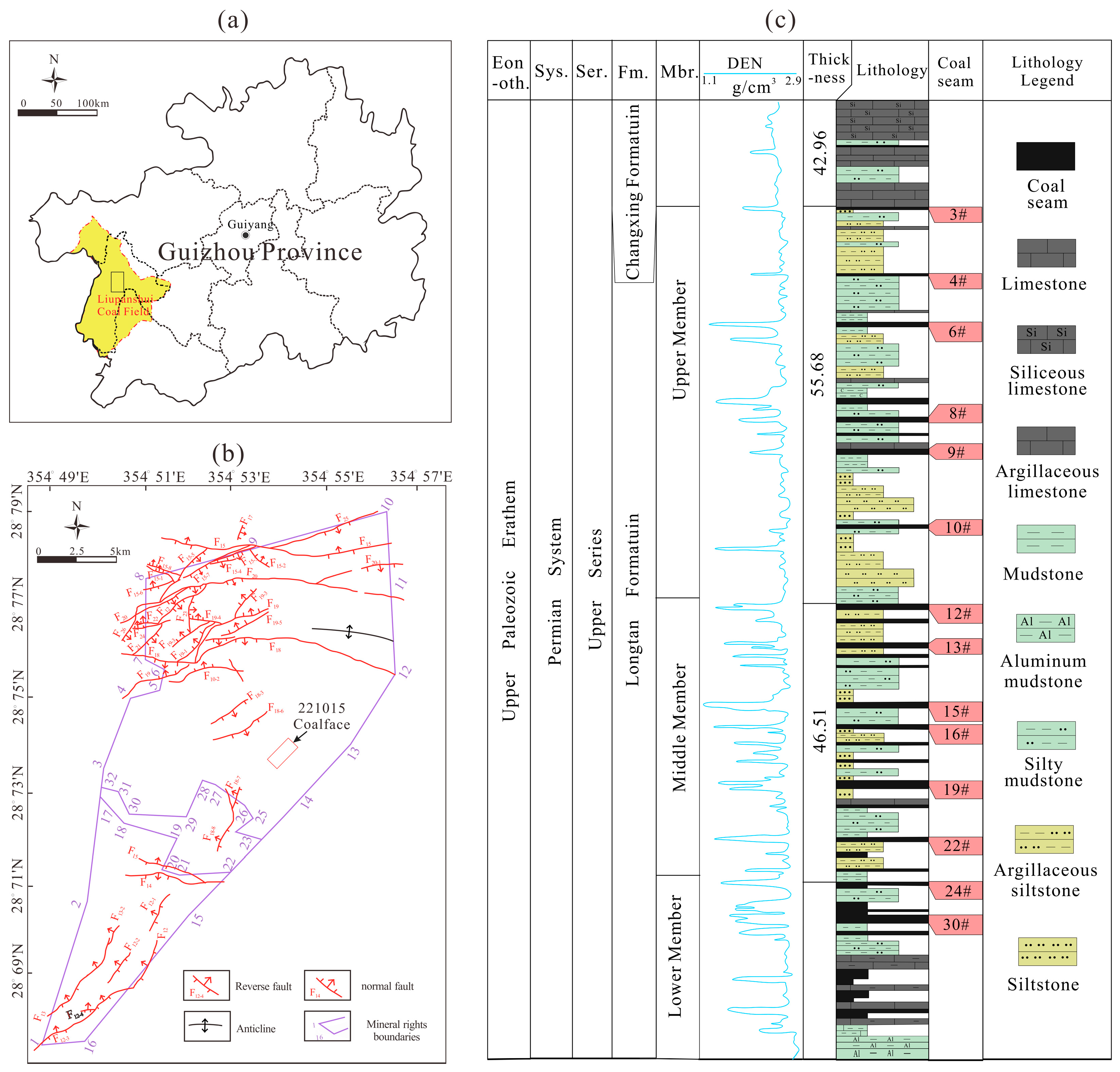

2.1. Geologic Background of the Study Area

2.2. Governing Equations

2.2.1. Mechanical Constitutive Relationship of Coal

2.2.2. Gas Quantity Equation of Coal

2.2.3. Gas Transportation Equation of Coal

2.2.4. Evolution Model of Coal Porosity and Permeability

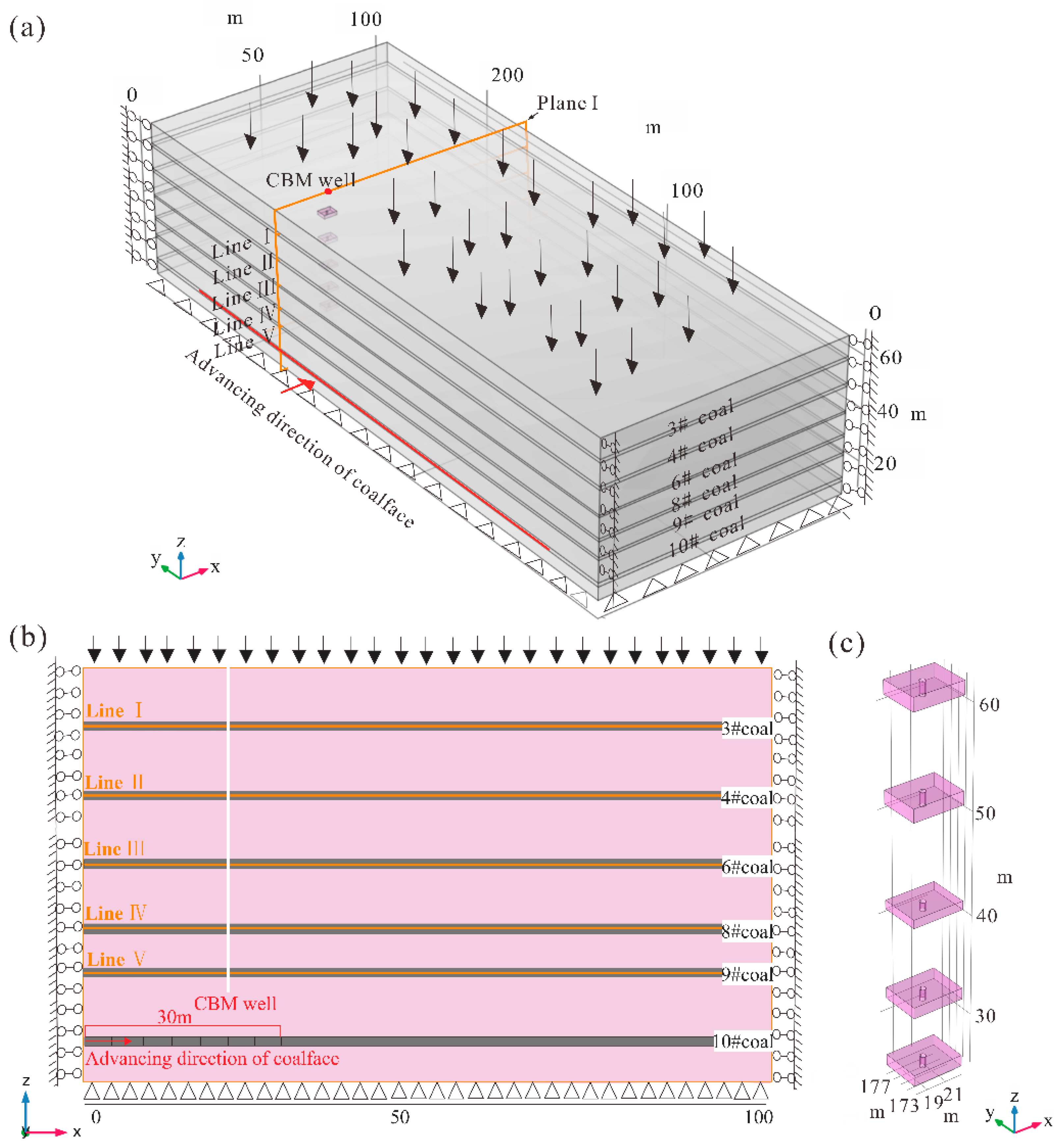

2.3. Geological-Engineering Model of the Study Area

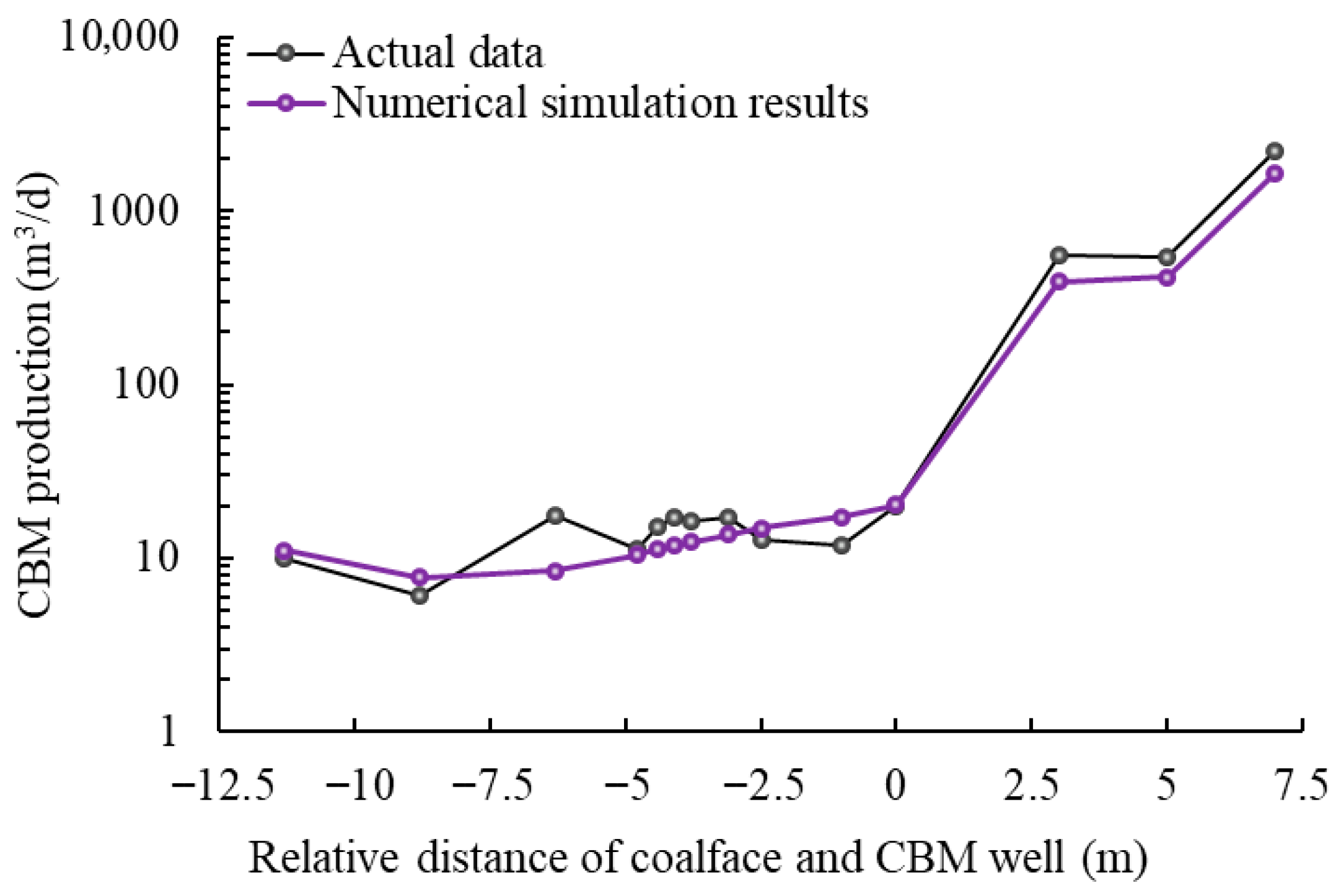

2.4. Model Validation

2.5. Numerical Simulation Schemes

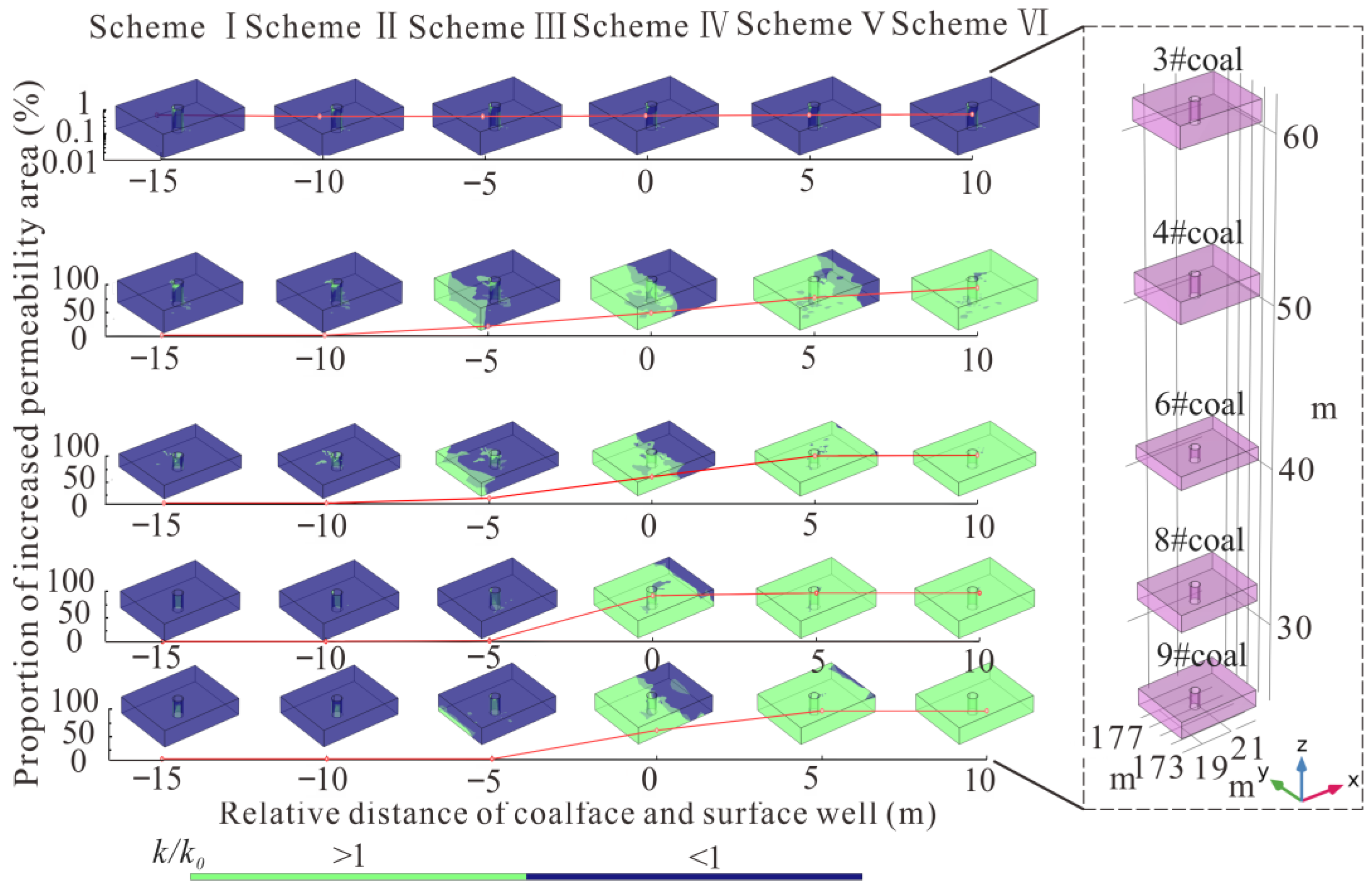

3. Results

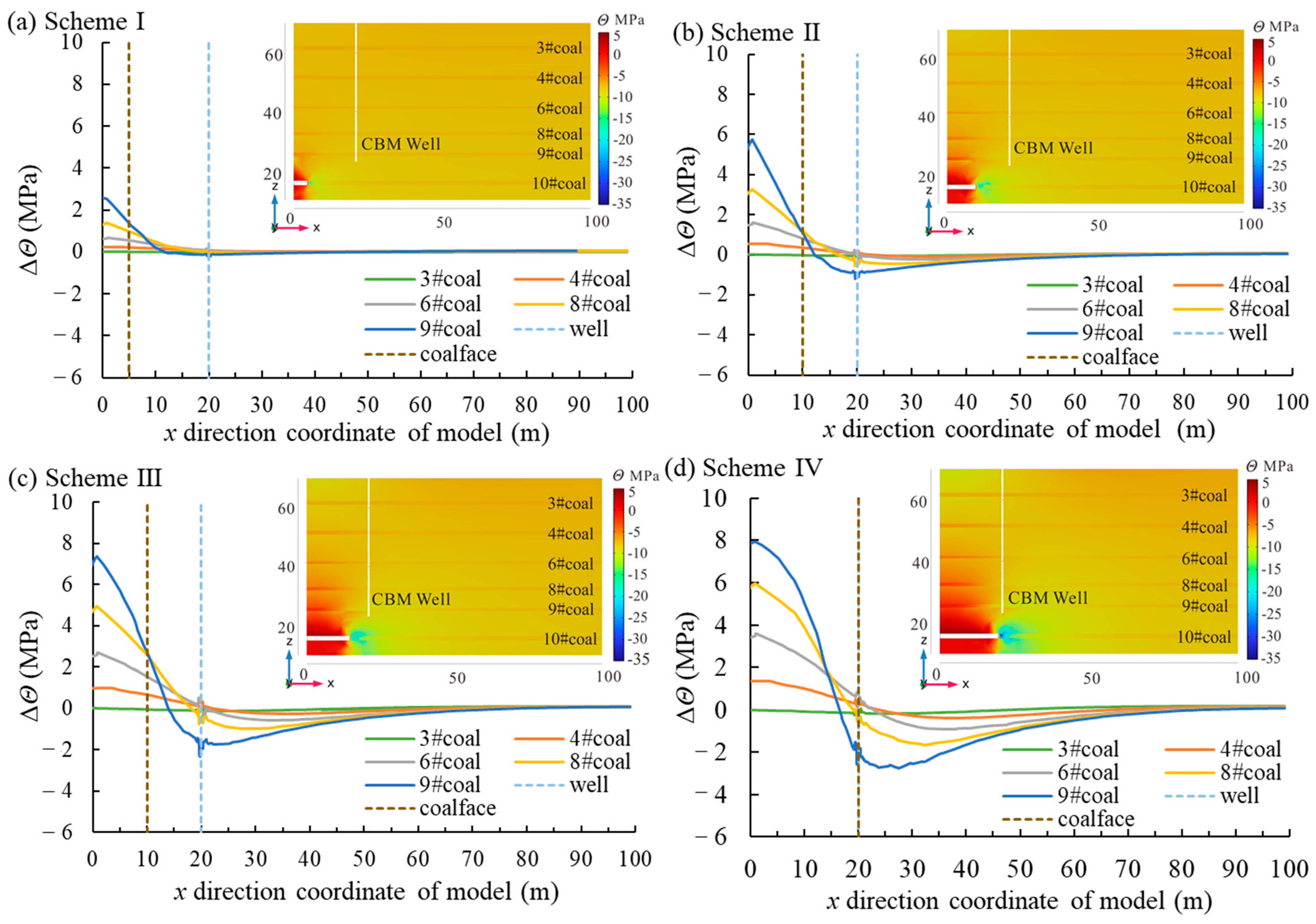

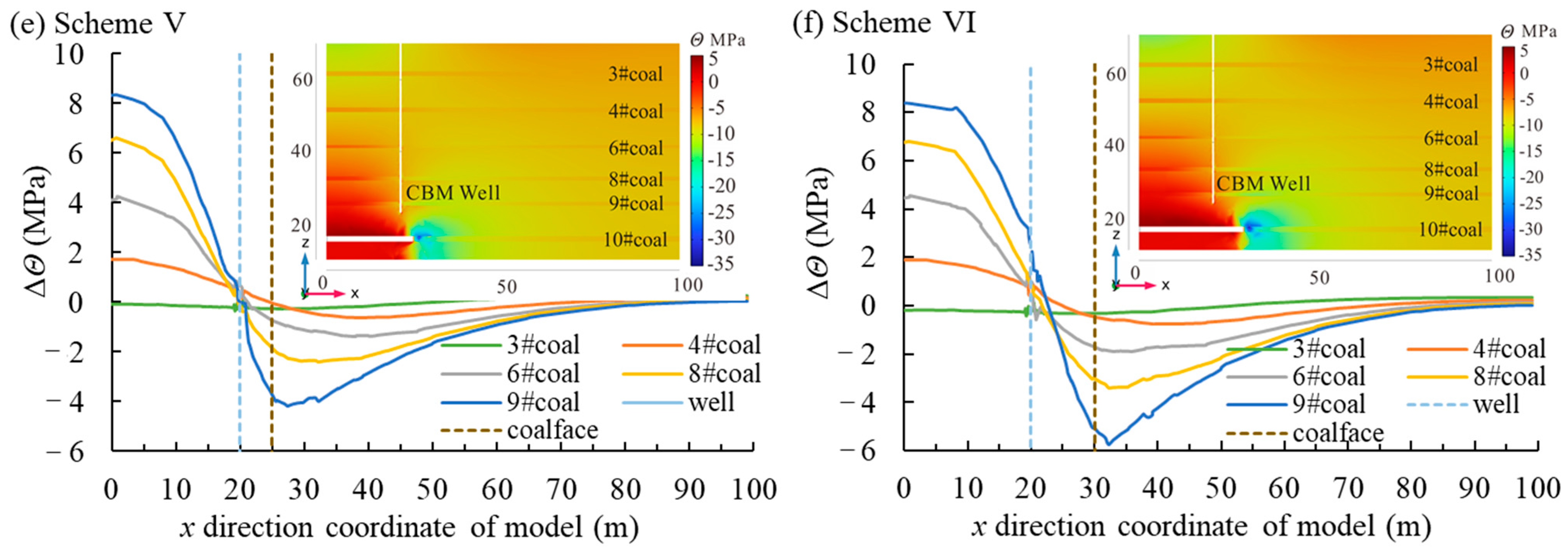

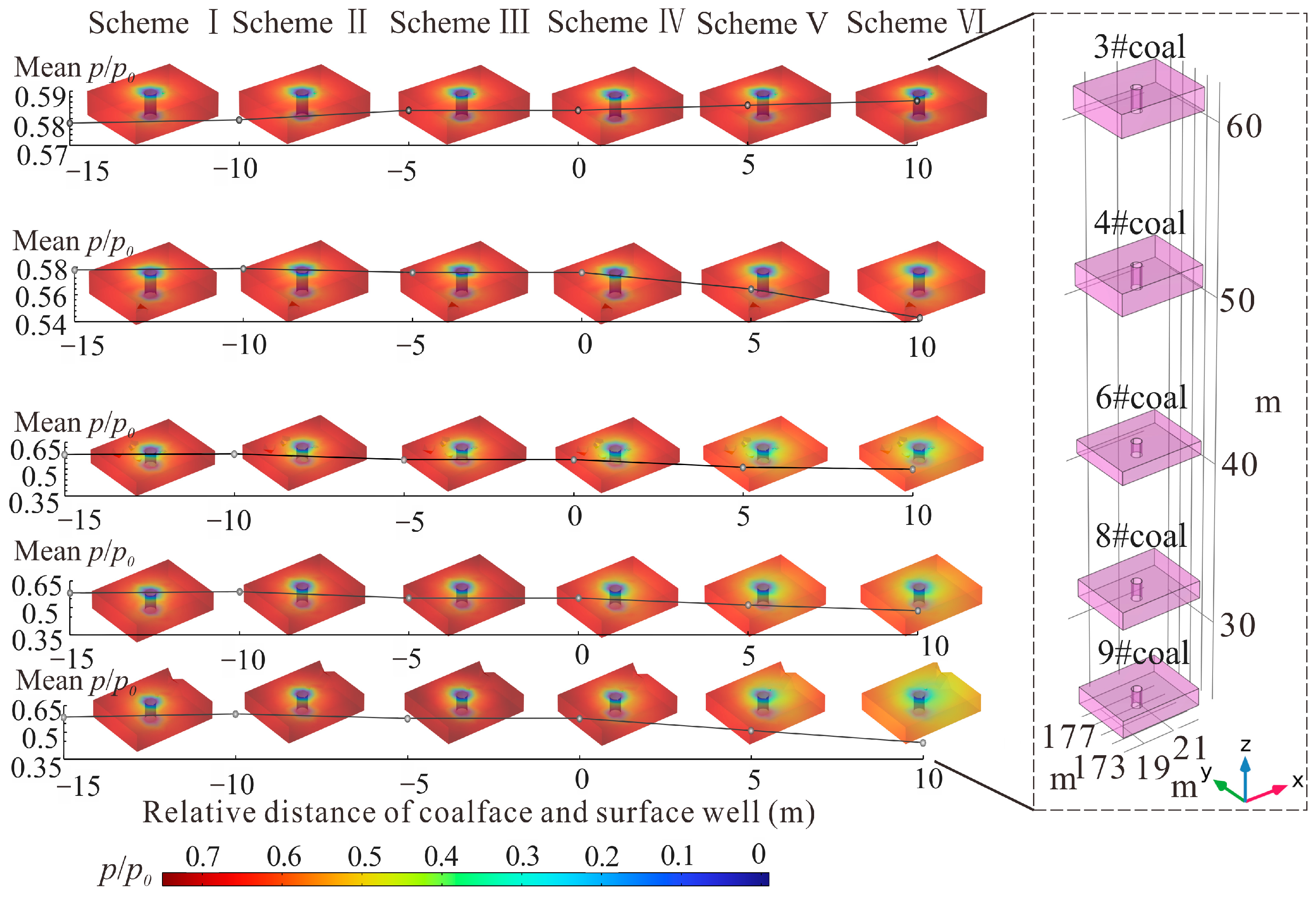

3.1. Mining Influence on Stress of Protected Seams

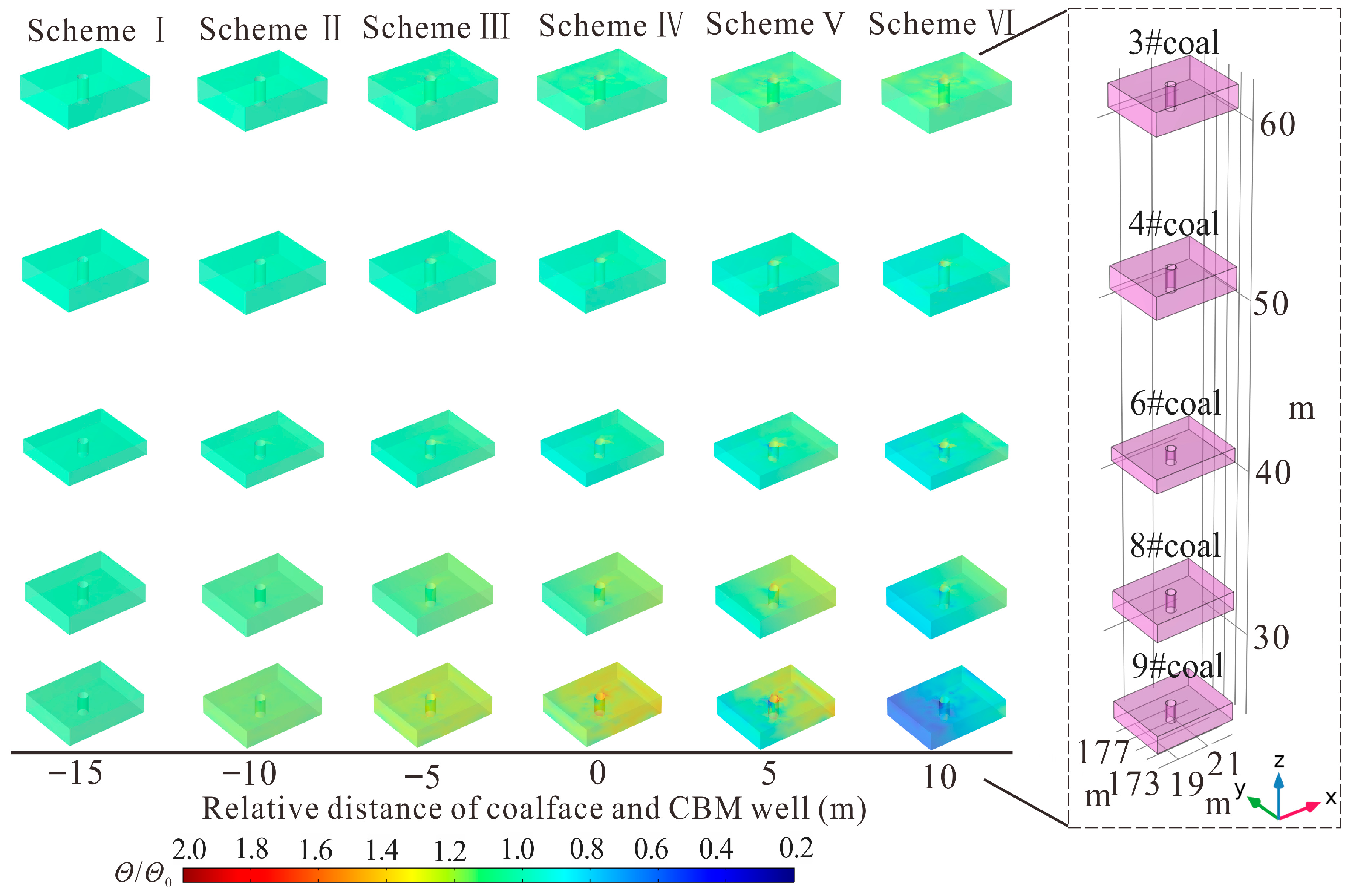

3.2. Mining Influence on Strain of Protected Seams

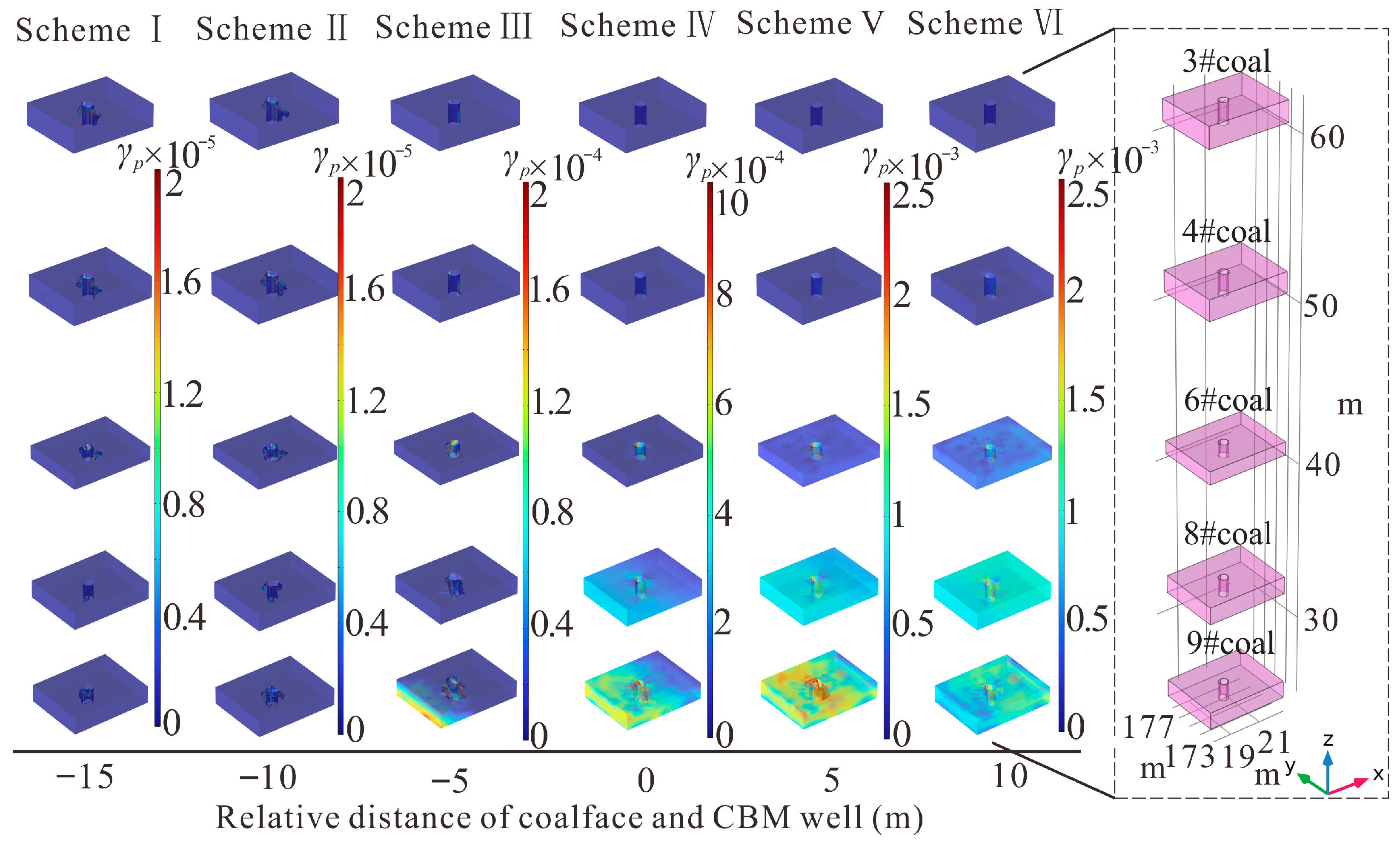

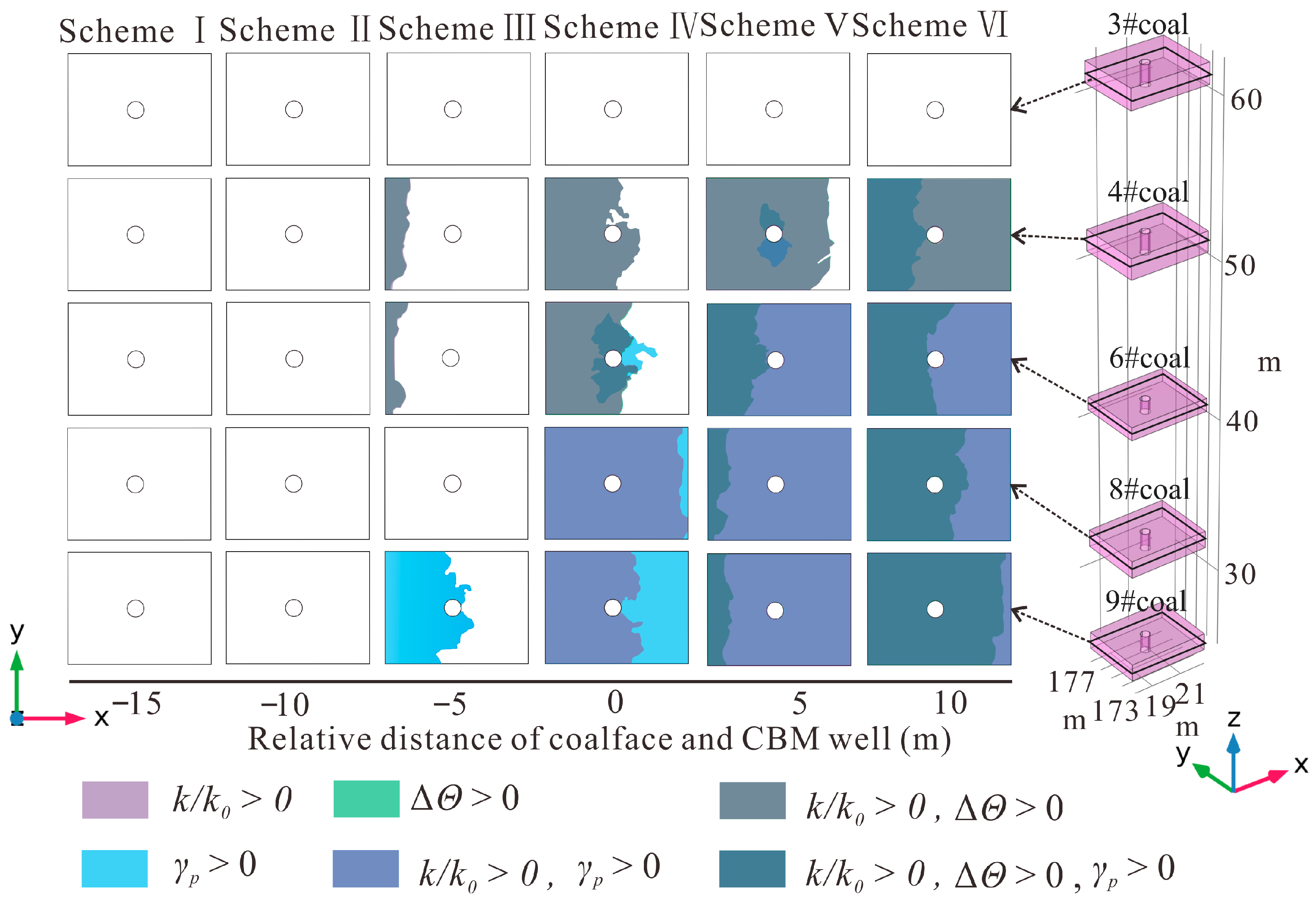

3.3. Mining Influence on Permeability of Protected Seams

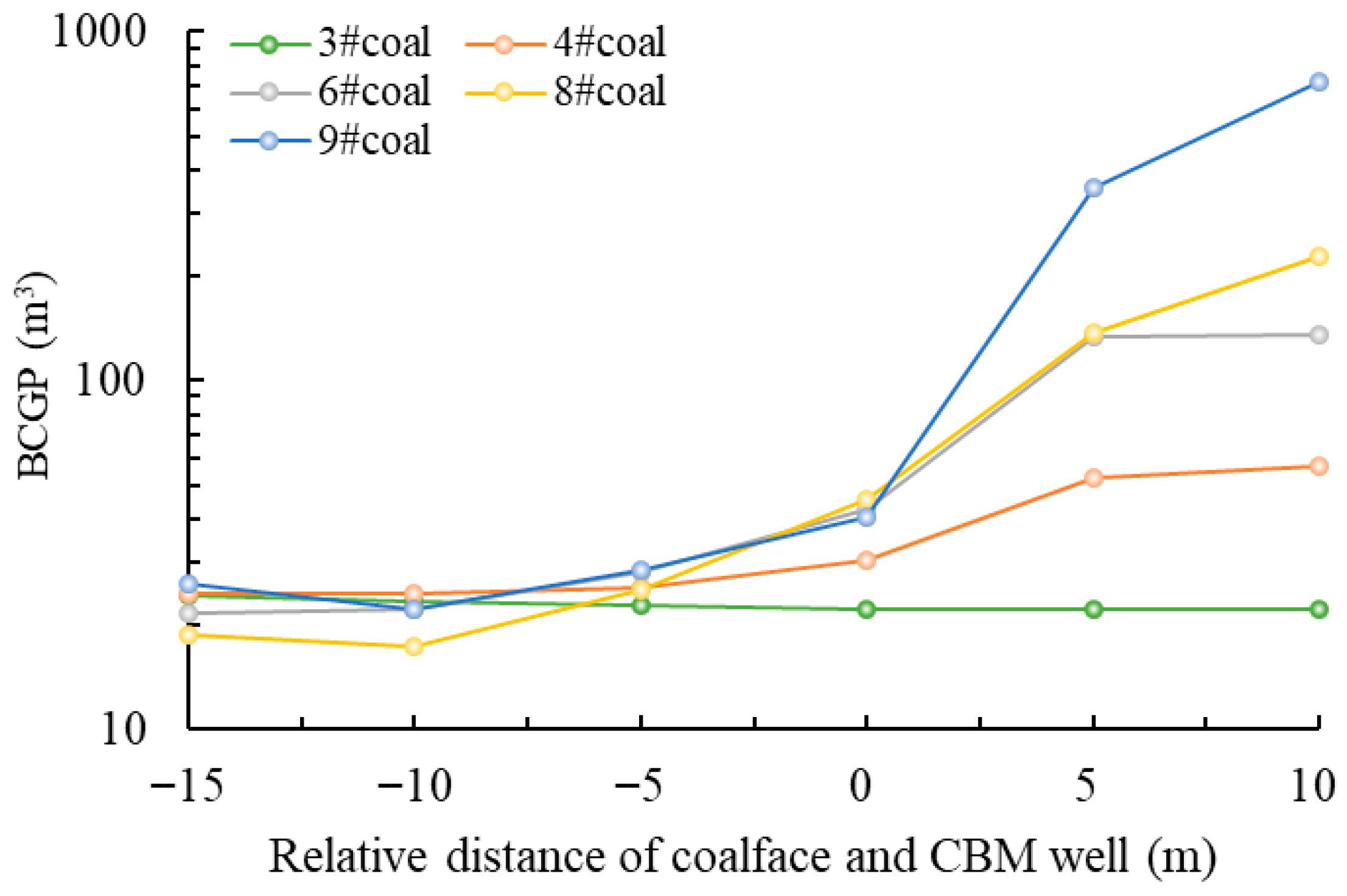

3.4. Mining Influence on CBM Well Production

4. Discussion

4.1. Mining Influence on the Evolution Law of Physical Properties, Mechanical Properties and Gas Seepage Behavior of Protected Seams

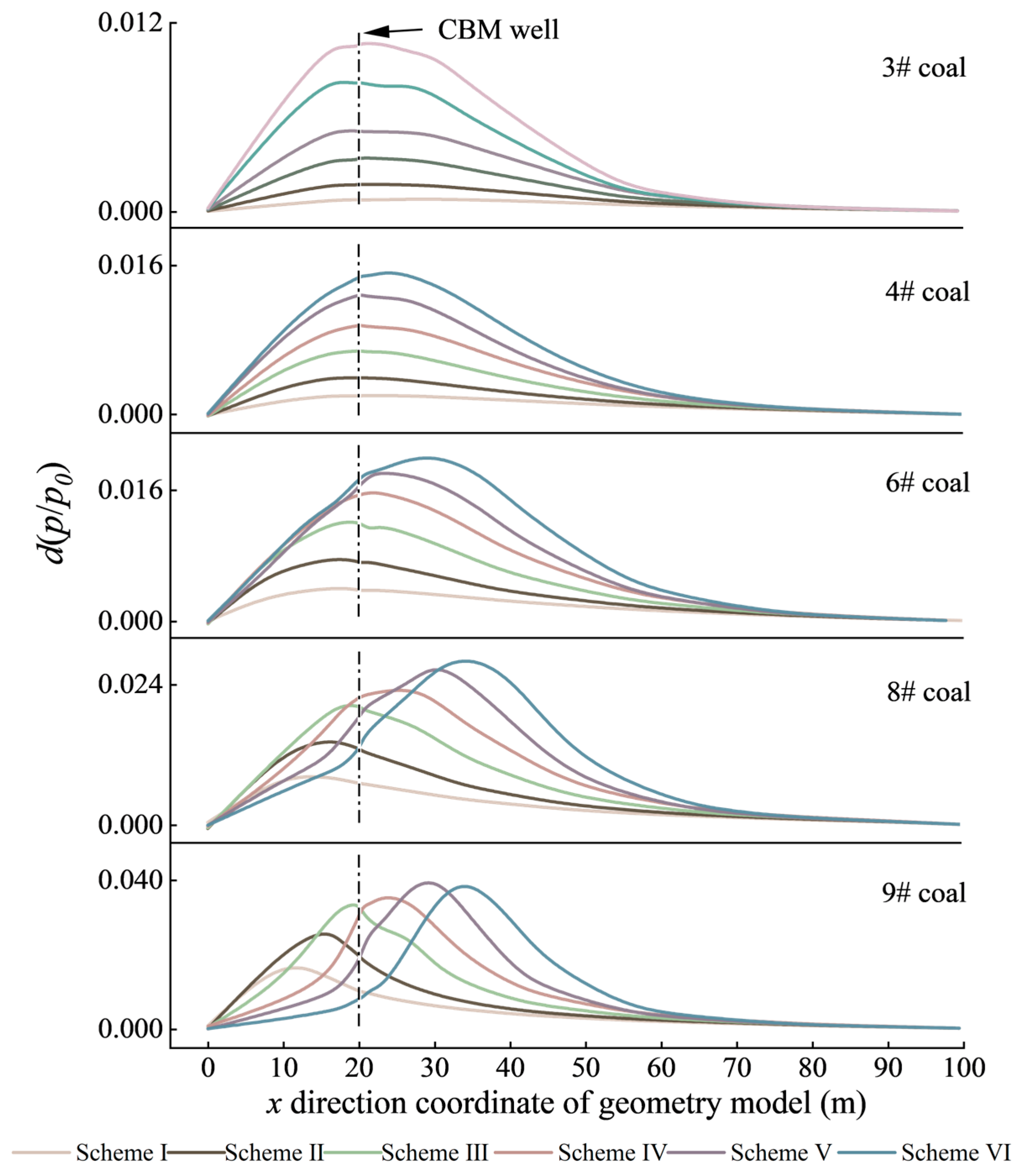

4.2. Control Mechanism of Permeability and Gas Pressure Gradient on CBM Well Production

4.3. Reasonable Start-Extraction Time of CBM Well and Its Application Prospect

5. Conclusions

- In mining areas, protected seams exhibit five permeability models under the combined influence of stress and strain. Distant protected seams develop only in the ECIPDM. Medium-distance protected seams successively exhibit the ECIPIM, ESIPDM, and PEIPIM. Close-distance protected seams evolve through the ECIPDM, PCIPDM, PSIPIM, and PEIPIM, with the latter two models primarily enhancing coal seam permeability and CBM production.

- During coal mining activities, the significant desorption and migration of CBM occur in protected seams. In permeability decrease zones, gas migration is hindered, leading to an elevated gas pressure gradient. This phenomenon, in conjunction with only a minor permeability reduction, can result in enhanced gas production. Conversely, when permeability increases, it becomes the controlling factor for gas production.

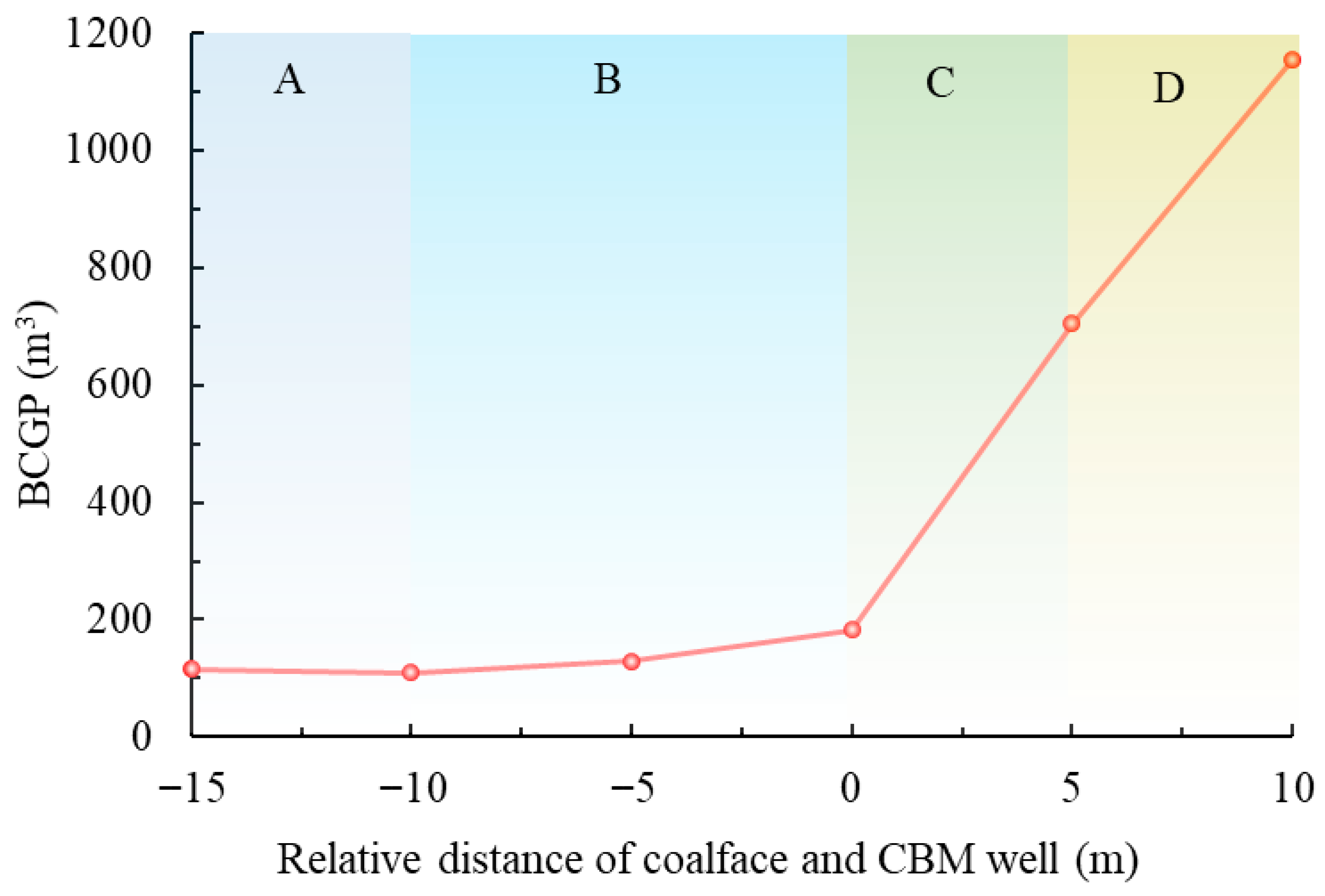

- Under the influence of permeability and the gas pressure gradient, the BCGP of the CBM well undergoes four types of variation: gradual decrease, slow rebound, rapid increase, and further surge. The onset of the rapid increase stage defines the optimal start-extraction time, which in the study area coincides with the coalface reaching the well location.

- The optimal start-extraction time shortens the extraction duration by at least 5.75 days and reduces electricity consumption by at least 2.07·104 kWh in study area. Influenced by coal structure and mining parameters, the optimal start-extraction time for the CBM well varies across different regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| G | Shear modulus, MPa |

| ui | Displacement along the i-direction, m |

| αm | Coefficient of the pore effective stress, MPa |

| αf | Coefficient of the fracture effective stress, MPa |

| pm | Gas pressure of coal matrix, MPa |

| pf | Gas pressure of coal fracture, MPa |

| δij | Kronecker delta coefficient |

| K | Bulk modulus, MPa |

| Fi | Body stress along the i-direction, MPa |

| C | Cohesion, MPa |

| φ | Internal friction angle, ° |

| I1 | First invariant of the stress tensor |

| J2 | Second invariant associated with the deviatoric stress tensor |

| C0 | Initial cohesion, MPa |

| Cr | Residual cohesion, MPa |

| γp | Equivalent plastic strain |

| γp* | γp at the commence of the residual stage |

| , , | Principal plastic strains |

| ϕf | Coal fracture porosity |

| M | Has molar mass, kg·mol−1 |

| R | Universal gas constant, 8.314, J mol−1·K |

| T | Environment temperature, K |

| ϕm | Coal matrix porosity |

| VL | Langmuir volume, m3 |

| PL | Langmuir pressure, MPa |

| Vstd | Gas molar volume, 0.0224, m3/mol |

| ϑ | Shape factor, m−2 |

| D | Gas diffusion coefficient, m−2·s−1 |

| μ | Gas viscosity coefficient, MPa·s |

| k0 | Initial coal permeability |

| bσ | Volume stress coefficient |

| Θ | Volume stress, MPa. |

| Cf | Fracture compression coefficient, MPa−1 |

| Mean principal stress, MPa | |

| fm | Internal expansion coefficient |

| Adsorption-induced strain. |

References

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, F.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Disaster-causing mechanism of spalling rock burst based on folding catastrophe model in coal mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 7591–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Sang, S.; Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, S.; Han, S.; Cai, J. Competitive adsorption-penetration characteristics of multi-component gases in micro-nano pore of coal. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, A.; Qu, Q. A formalism to compute permeability changes in anisotropic fractured rocks due to arbitrary deformations. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 125, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Xue, Y.; Du, F.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhai, M.; et al. Diffusion evolution rules of grouting slurry in mining-induced cracks in overlying strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 6493–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, B.; Cheng, W.; Lei, B.; Shi, H.; Chen, L. Investigation of permeability evolution in the lower slice during thick seam slicing mining and gas drainage: A case study from the Dahuangshan coalmine in China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 52, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Wang, K.; Du, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y. Mechanical properties and permeability evolution of gas-bearing coal under phased variable speed loading and unloading. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Xia, B.; Su, X.; Shen, Z. Numerical Investigation of 3D Distribution of Mining-Induced Fractures in Response to Longwall Mining. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 30, 889–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, K. Numerical assessment of CMM drainage in the remote unloaded coal body: Insights of geostress-relief gas migration and coal permeability. Nat. Resour. Res. 2017, 45, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, S. Evaluation of permeability damage for stressed coal with cyclic loading: An experimental study. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 216, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, Y. The elimination of coal and gas outburst disasters by long distance lower protective seam mining combined with stress-relief gas extraction in the Huaibei coal mine area. Nat. Resour. Res. 2015, 27, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wen, H.; Cheng, X.; Fan, S.; Ye, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Lin, J. Characteristics of Pressure Relief Gas Extraction in the Protected Layer by Surface Drilling in Huainan. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9966843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Li, B.; Dong, J.; Liu, Q. Optimal selection of coal seam pressure-relief gas extraction technologies: A typical case of the Panyi Coal Mine, Huainan coalfield, China. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 44, 1105–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Separation and fracturing in overlying strata disturbed by longwall mining in a mineral deposit seam. Eng. Geol. 2017, 226, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremin, M.; Esterhuizen, G.; Smolin, I. Numerical simulation of roof cavings in several Kuzbass mines using finite-difference continuum damage mechanics approach. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 30, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yuan, L.; Shen, B.; Qu, Q.; Xue, J. Mining-induced strata stress changes, fractures and gas flow dynamics in multi-seam longwall mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012, 54, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Li, G.; Yang, Y. Study on key technology for surface extraction of coalbed methane in coal mine goaf from Sihe Wells Area, Jincheng. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 49, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhao, H.; Ji, D.; Cui, L. Evolution of mining stress field and the control technology of stress relief gas in close distance coal seam. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2022, 40, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Fu, X.; Kang, J.; Tian, Z.; Shen, Y. Experimental Study on the Change of the Pore-Fracture Structure in Mining-Disturbed Coal-Series Strata: An Implication for CBM Development in Abandoned Mines. Energy Fuels. 2020, 35, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, W. A numerical model for outburst including the effect of adsorbed gas on coal deformation and mechanical properties. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 54, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Ju, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhao, W.; Du, C.; Guo, Y.; Lou, Z.; Gao, H. Numerical study on the mechanism of air leakage in drainage boreholes: A fully coupled gas-air flow model considering elastic-plastic deformation of coal and its validation. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2021, 158, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Tian, H. Technical scheme and application of pressure-relief gas extraction in multi-coal seam mining region. Int. J. Min. Sci. 2018, 28, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D.; Chen, J. Study on time–space characteristics of gas drainage in advanced self-pressure-relief area of the stope. Energy Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, Z.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. Intensive field measurements for characterizing the permeability and methane release with the treatment process of pressure-relief mining. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Lin, B. Fluid–Solid Coupling Characteristics of Gas-Bearing Coal Subjected to Hydraulic Slotting: An Experimental Investigation. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, M.; Zou, Q.; Li, J.; Lin, M.; Lin, B. Crack instability in deep coal seam induced by the coupling of mining unloading and gas driving and transformation of failure mode. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 170, 105526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H. Evaluation of the remote lower protective seam mining for coal mine gas control: A typical case study from the Zhuxianzhuang Coal Mine, Huaibei Coalfield, China. Nat. Resour. Res. 2016, 33, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Study on Numerical Simulation and Application of Gob Coal Seam Gas Well Productivity in Longwall Working Face. Ph.D. Thesis, China Coal Research Institute, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tu, S.; Yuan, Y.; Hao, D. Sensitivity analysis of longwall panel advancing rate on extraction of pressure relief gas. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2017, 34, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Study on Drainage system and matching technology of surface well in goaf of test area in Pan Zhuang Mine Field. China Coalbed Methane. 2018, 15, 1–4+16. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, D.; Prager, W.; Greenberg, H. Soil mechanics and plastic analysis or limit design. Q. Appl. Math. 1952, 9, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Shang, Z. A novel technology for enhancing coalbed methane extraction: Hydraulic cavitating assisted fracturing. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 72, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Sa, Z.; Wang, L. Numerical assessment of the energy instability of gas outburst of deformed and normal coal combinations during mining. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2019, 132, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, L.; Dong, J.; Wang, L.; Qi, Y.; Wang, W. A novel in-seam borehole hydraulic flushing gas extraction technology in the heading face: Enhanced permeability mechanism, gas flow characteristics, and application. Nat. Resour. Res. 2017, 46, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, B. Evolution of mechanical behavior and its influence on coal permeability during dual unloading. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 47, 2656–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z. Study on Crack Evolution and Permeability Characteristic of Protective Coal Seam Mining in Close Coal Seams Group. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Qi, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Evolution of the superimposed mining induced stress-fissure field under extracting of close distance coal seam group. J. China Coal Soc. 2014, 41, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Zeng, X. A Mini-Review on Coal Permeability under Combined Thermal and Mechanical Effects. Energ Fuels. 2025, 39, 21659–21676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Parameter | Value of Coal Seams | Value of Non-Coal Seams |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ρ | Density | 1400 | 2500 |

| E | Bulk modulus | 640 | 2000 |

| Φ | Internal friction angle | 38 | 32 |

| C0 | Initial cohesion | 1.5 | 7.3 |

| k0 | Initial permeability | 0.06 | 1 |

| ϕm | Initial fracture porosity | 0.012 | 0.03 |

| ϕf | Initial pore porosity | 0.049 | 0.1 |

| Cr | Residual cohesion | 1.2 | |

| γp* | Initial residual equivalent plastic strain | 0.01 | |

| VL | Langmuir volume | 28 | |

| PL | Langmuir volume | 2 | |

| Cf | Fracture compressibility coefficient | 0.1412 | |

| Maximum sorption-induced strain | 0.012 | ||

| fm | Internal expansion coefficient | 0.1 | |

| ξ | Increase coefficient of permeability | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, P.; Xu, A.; Sun, X.; Zhou, X.; Han, S.; Dong, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, W.; Feng, Y. Optimization of Start-Extraction Time for Coalbed Methane Well in Mining Area Using Fluid–Solid Coupling Numerical Simulation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310712

Zhou P, Xu A, Sun X, Zhou X, Han S, Dong J, Chen J, Gao W, Feng Y. Optimization of Start-Extraction Time for Coalbed Methane Well in Mining Area Using Fluid–Solid Coupling Numerical Simulation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310712

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Peiming, Ang Xu, Xueting Sun, Xiaozhi Zhou, Sijie Han, Jihang Dong, Jie Chen, Wei Gao, and Yunfei Feng. 2025. "Optimization of Start-Extraction Time for Coalbed Methane Well in Mining Area Using Fluid–Solid Coupling Numerical Simulation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310712

APA StyleZhou, P., Xu, A., Sun, X., Zhou, X., Han, S., Dong, J., Chen, J., Gao, W., & Feng, Y. (2025). Optimization of Start-Extraction Time for Coalbed Methane Well in Mining Area Using Fluid–Solid Coupling Numerical Simulation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310712