Proposal for a New Indicator of the Economic Dimension of Sustainable Development: The Unproductive Employment Rate (UER)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

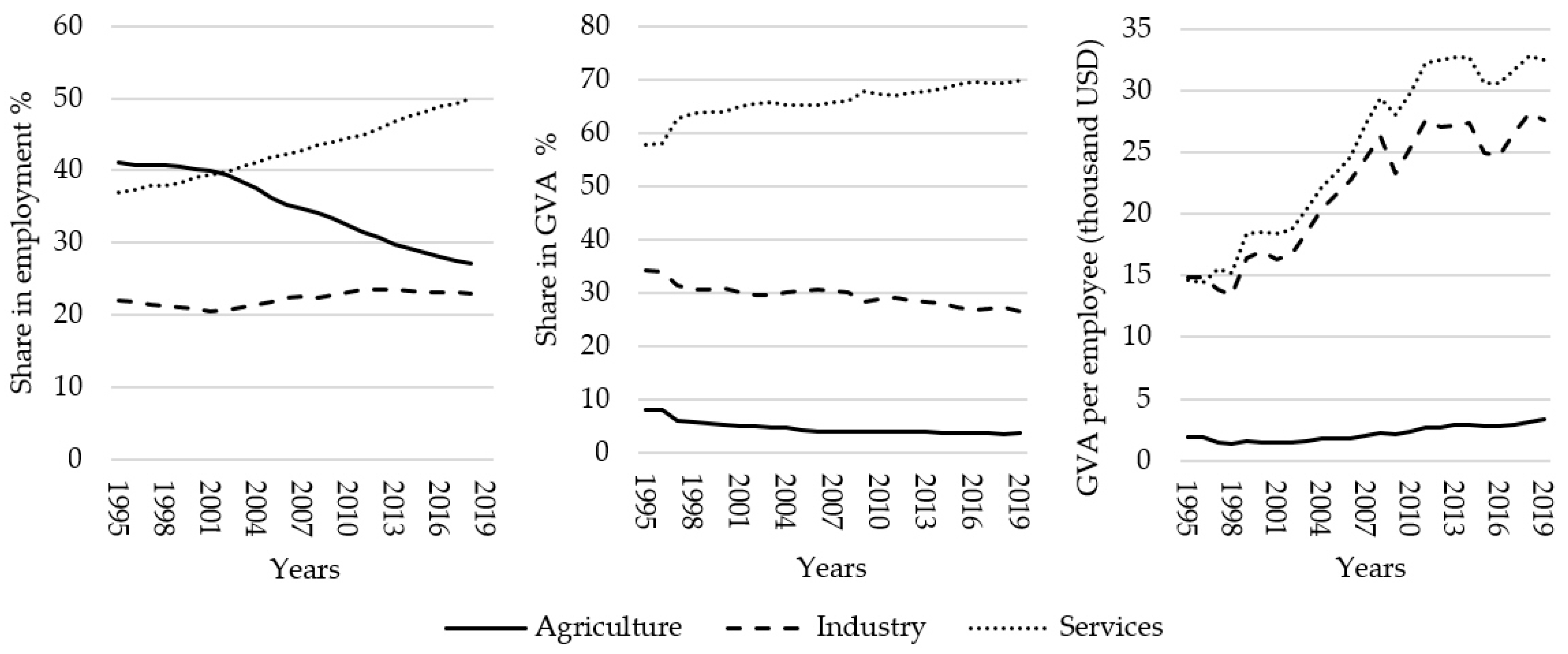

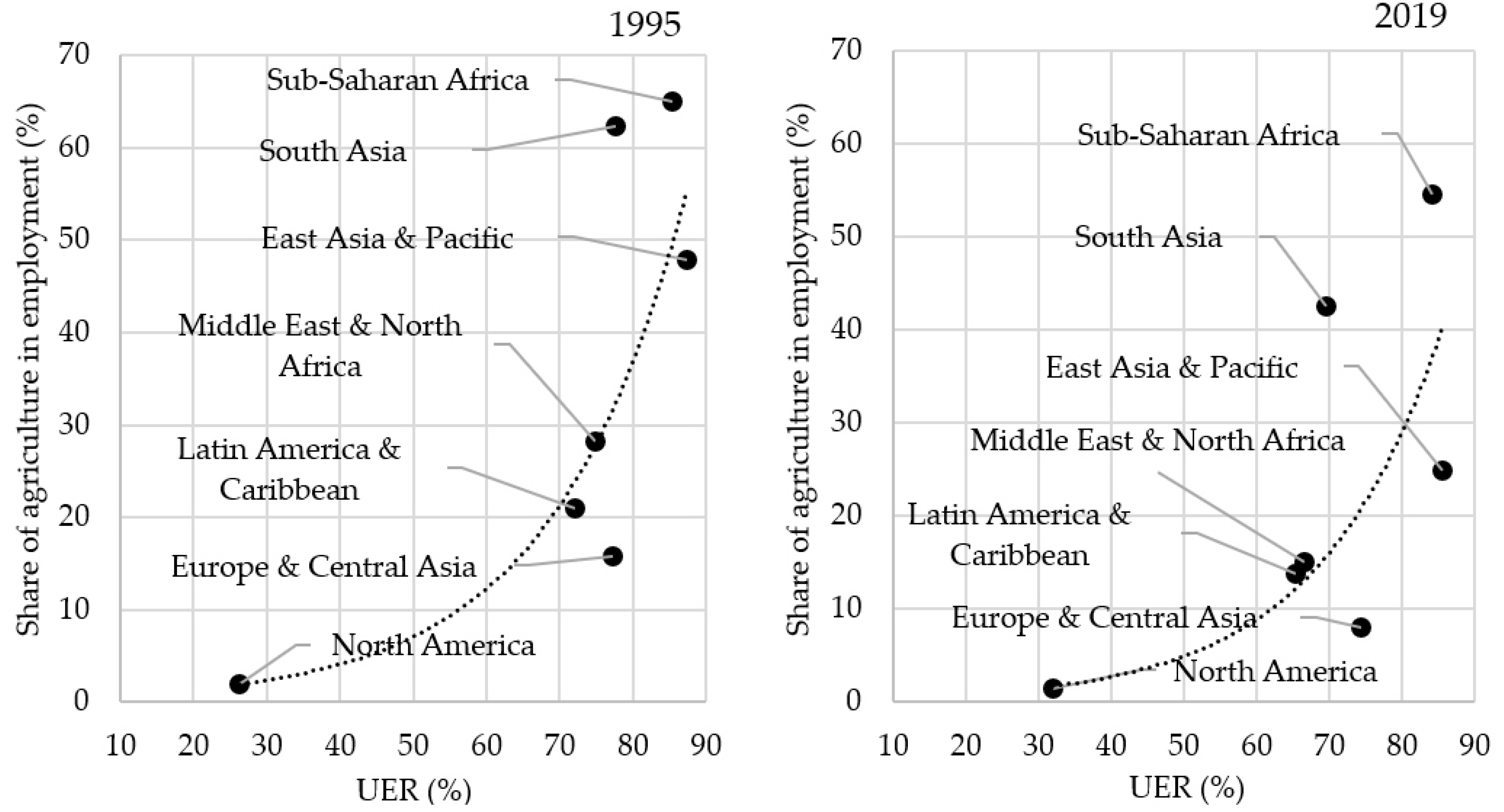

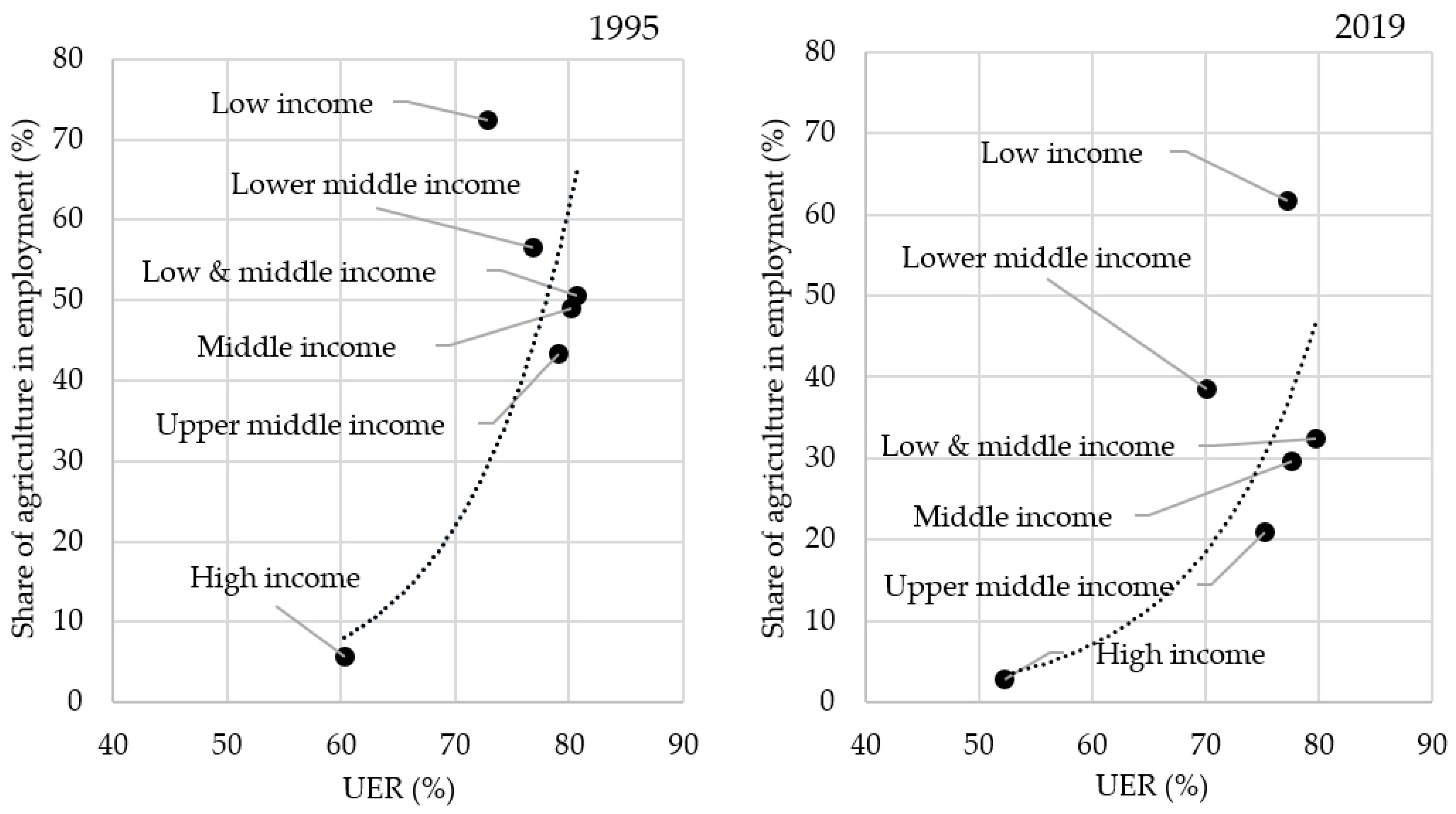

2.1. Unproductive Labour and Surplus Employment

2.2. The Issue of Low Labour Productivity in Agriculture

2.3. Optimal Level and Unproductive Employment in Agriculture

2.4. Sustainable Development Goals and Their Indicators

- Goal 1—No poverty (sdg_01);

- Goal 2—Zero hunger (sdg_02);

- Goal 3—Good health and well-being (sdg_03);

- Goal 4—Quality education (sdg_04);

- Goal 5—Gender equality (sdg_05);

- Goal 6—Clean water and sanitation (sdg_06);

- Goal 7—Affordable and clean energy (sdg_07);

- Goal 8—Decent work and economic growth (sdg_08);

- Goal 9—Industry, innovation, and infrastructure (sdg_09);

- Goal 10—Reduced inequalities (sdg_10);

- Goal 11—Sustainable cities and communities (sdg_11);

- Goal 12—Responsible consumption and production (sdg_12);

- Goal 13—Climate action (sdg_13);

- Goal 14—Life below water (sdg_14);

- Goal 15—Life on land (sdg_15);

- Goal 16—Peace, justice, and strong institutions (sdg_16);

- Goal 17—Partnerships for the goals (sdg_17).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construction of the Indicator

- and

3.2. Limitations and Comments on the Interpretation of the UER

3.3. Data Collection Used in the Presented Application Examples

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ea | Actual employment in agriculture |

| Ear | Actual share of agriculture in total employment |

| Eis | Total employment in industry and services |

| Etotal | Total number of employees in the economy |

| GVA | Gross value added |

| GVAa | GVA in the agricultural sector |

| GVAi | GVA in the industry |

| GVAisp | GVA per employee in industry and services on average |

| GVAs | GVA in services |

| OEa | Optimal employment in agriculture |

| OEra | Optimal employment rate in agriculture (share of the total number of employees in the economy) |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UEa | Unproductive employment in agriculture |

| UER | Unproductive employment rate |

Appendix A

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | J | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etotal (Thousands Employees) | Ea (Thousands Employees) | Eis (Thousands Employees) | GVAa (Thousands USD) | GVAis (Thousands USD) | GVAap (Thousands USD) | GVAisp (Thousands USD) | Ear (%) | UER (%) | UEa (Thousands Employees) | OEa (Thousands Employees) | OEra (%) | |

| World Bank Data | D/B | E/C | B/A × 100 | (1 − D/G/B) 100 | B × I | B − K | J/A × 100 | |||||

| East Asia and Pacific | 1,026,605 | 491,321 | 535,284 | 846,956 | 7,322,798 | 1.7 | 13.7 | 47.9 | 87.4 | 429,410 | 61,911 | 6.0 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 389,177 | 61,486 | 327,691 | 197,696 | 4,650,841 | 3.2 | 14.2 | 15.8 | 77.3 | 47,557 | 13,929 | 3.6 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 191,773 | 40,216 | 151,558 | 120,761 | 1,633,037 | 3.0 | 10.8 | 21.0 | 72.1 | 29,008 | 11,208 | 5.8 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 78,036 | 22,057 | 55,979 | 61,180 | 616,826 | 2.8 | 11.0 | 28.3 | 74.8 | 16,504 | 5552 | 7.1 |

| North America | 149,689 | 2968 | 146,721 | 130,173 | 8,730,755 | 43.9 | 59.5 | 2.0 | 26.3 | 780 | 2188 | 1.5 |

| South Asia | 443,554 | 276,091 | 167,463 | 118,105 | 320,240 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 62.2 | 77.6 | 214,330 | 61,761 | 13.9 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 218,252 | 141,729 | 76,523 | 72,281 | 266,929 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 64.9 | 85.4 | 121,007 | 20,721 | 9.5 |

| Pre-demographic dividend | 172,243 | 113,277 | 58,967 | 44,053 | 122,736 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 65.8 | 81.3 | 92,112 | 21,164 | 12.3 |

| Early-demographic dividend | 810,103 | 424,138 | 385,965 | 354,584 | 2,010,302 | 0.8 | 5.2 | 52.4 | 83.9 | 356,060 | 68,078 | 8.4 |

| Late-demographic dividend | 1,024,568 | 472,596 | 551,972 | 398,443 | 2,500,612 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 46.1 | 81.4 | 384,645 | 87,950 | 8.6 |

| Post-demographic dividend | 480,737 | 29,888 | 450,849 | 387,617 | 17,859,188 | 13.0 | 39.6 | 6.2 | 67.3 | 20,102 | 9785 | 2.0 |

| Low income | 127,009 | 92,016 | 34,993 | 32,525 | 50,738 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 72.4 | 75.6 | 69,584 | 22,432 | 17.7 |

| Low and middle income | 2,002,028 | 1,012,171 | 989,857 | 763,494 | 4,021,411 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 50.6 | 81.4 | 824,239 | 187,931 | 9.4 |

| Lower middle income | 816,966 | 461,958 | 355,008 | 266,183 | 932,079 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 56.5 | 78.1 | 360,575 | 101,383 | 12.4 |

| Middle income | 1,875,019 | 919,995 | 955,024 | 733,344 | 3,967,483 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 49.1 | 80.8 | 743,470 | 176,525 | 9.4 |

| Upper middle income | 1,058,053 | 458,201 | 599,852 | 472,206 | 3,029,368 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 43.3 | 79.6 | 364,698 | 93,503 | 8.8 |

| High income | 495,059 | 27,760 | 467,299 | 413,976 | 18,948,749 | 14.9 | 40.5 | 5.6 | 63.2 | 17,551 | 10,209 | 2.1 |

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | J | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etotal (Thousands Employees) | Ea (Thousands Employees) | Eis (Thousands Employees) | GVAa (Thousands USD) | GVAis (Thousands USD) | GVAap (Thousands USD) | GVAisp (Thousands USD) | Ear (%) | UER (%) | UEa (Thousands Employees) | Oea (Thousands Employees) | Oera (%) | |

| World Bank Data | D/B | E/C | B/A × 100 | (1 − D/G/B) × 100 | B × I | B − K | J/A × 100 | |||||

| East Asia and Pacific | 1,266,543 | 314,923 | 951,621 | 1,178,681 | 24,731,545 | 3.7 | 26.0 | 24.9 | 85.6 | 269,569 | 45,353 | 3.6 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 437,926 | 34,891 | 403,035 | 445,024 | 20,007,092 | 12.8 | 49.6 | 8.0 | 74.3 | 25,926 | 8965 | 2.0 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 309,380 | 42,530 | 266,850 | 270,072 | 4,888,291 | 6.4 | 18.3 | 13.7 | 65.3 | 27,787 | 14,743 | 4.8 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 149,586 | 22,478 | 127,108 | 188,760 | 3,202,675 | 8.4 | 25.2 | 15.0 | 66.7 | 14,986 | 7491 | 5.0 |

| North America | 185,901 | 2588 | 183,313 | 212,474 | 22,132,421 | 82.1 | 120.7 | 1.4 | 32.0 | 829 | 1760 | 0.9 |

| South Asia | 664,285 | 282,553 | 381,732 | 604,475 | 2,682,486 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 42.5 | 69.6 | 196,533 | 86,020 | 12.9 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 415,312 | 226,695 | 188,618 | 262,064 | 1,374,893 | 1.2 | 7.3 | 54.6 | 84.1 | 190,743 | 35,952 | 8.7 |

| Pre-demographic dividend | 331,374 | 180,381 | 150,993 | 249,418 | 1,082,875 | 1.4 | 7.2 | 54.43 | 80.7 | 145,603 | 34,778 | 10.5 |

| Early-demographic dividend | 1280,576 | 450,854 | 829,722 | 1,136,607 | 9,854,922 | 2.5 | 11.9 | 35.21 | 78.8 | 355,159 | 95,695 | 7.5 |

| Late-demographic dividend | 1,242,530 | 280,079 | 962,451 | 1,285,039 | 20,557,161 | 4.6 | 21.4 | 22.54 | 78.5 | 219,916 | 60,163 | 4.8 |

| Post-demographic dividend | 562,150 | 17,333 | 544,817 | 634,744 | 4,644,8974 | 36.6 | 85.3 | 3.08 | 57.0 | 9888 | 7445 | 1.3 |

| Low income | 245,022 | 150,986 | 94,035 | 119,992 | 329,796 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 61.62 | 77.3 | 116,773 | 34,214 | 14.0 |

| Low and middle income | 2,817,159 | 911,988 | 1,905,172 | 2,726,463 | 28,164,887 | 3.0 | 14.8 | 32.37 | 79.8 | 727,560 | 184,428 | 6.5 |

| Lower middle income | 1,259,995 | 485,153 | 774,841 | 1,142,691 | 6,120,229 | 2.4 | 7.9 | 38.50 | 70.2 | 340,485 | 144,668 | 11.5 |

| Middle income | 2,572,137 | 760,279 | 1,811,859 | 2,608,866 | 27,787,718 | 3.4 | 15.3 | 29.56 | 77.6 | 590,172 | 170,107 | 6.6 |

| Upper middle income | 1,312,143 | 273,940 | 1,038,202 | 1,414,947 | 21,715,723 | 5.2 | 20.9 | 20.88 | 75.3 | 206,293 | 67,647 | 5.2 |

| High income | 611,774 | 17,024 | 594,750 | 686,710 | 50,313,348 | 40.3 | 84.6 | 2.78 | 52.3 | 8906 | 8118 | 1.3 |

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | J | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etotal | Ea | Eis | GVAa | GVAis | GVAap | GVAisp | Ear | UER | UEa | OEa | Oera | |

| East Asia and Pacific | 123.4 | 64.1 | 177.8 | 139.2 | 337.7 | 217.1 | 190.0 | 52.0 | 97.9 | 62.8 | 73.3 | 59.4 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 112.5 | 56.7 | 123.0 | 225.1 | 430.2 | 396.7 | 349.8 | 50.4 | 96.1 | 54.5 | 64.4 | 57.2 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 161.3 | 105.8 | 176.1 | 223.6 | 299.3 | 211.5 | 170.0 | 65.6 | 90.6 | 95.8 | 131.5 | 81.5 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 191.7 | 101.9 | 227.1 | 308.5 | 519.2 | 302.7 | 228.7 | 53.2 | 89.1 | 90.8 | 134.9 | 70.4 |

| North America | 124.2 | 87.2 | 124.9 | 163.2 | 253.5 | 187.1 | 202.9 | 70.2 | 121.8 | 106.2 | 80.4 | 64.8 |

| South Asia | 149.8 | 102.3 | 227.9 | 511.8 | 837.6 | 500.1 | 367.5 | 68.3 | 89.6 | 91.7 | 139.3 | 93.0 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 190.3 | 159.9 | 246.5 | 362.6 | 515.1 | 226.7 | 209.0 | 84.1 | 98.5 | 157.6 | 173.5 | 91.2 |

| Pre-demographic dividend | 192.4 | 159.2 | 256.1 | 566.2 | 882.3 | 355.6 | 344.6 | 82.8 | 99.3 | 158.1 | 164.3 | 85.4 |

| Early-demographic dividend | 158.1 | 106.3 | 215.0 | 320.5 | 490.2 | 301.6 | 228.0 | 67.2 | 93.8 | 99.7 | 140.6 | 88.9 |

| Late-demographic dividend | 121.3 | 59.3 | 174.4 | 322.5 | 822.1 | 544.2 | 471.5 | 48.9 | 96.5 | 57.2 | 68.4 | 56.4 |

| Post-demographic dividend | 116.9 | 58.0 | 120.8 | 163.8 | 260.1 | 282.4 | 215.2 | 49.6 | 84.8 | 49.2 | 76.1 | 65.1 |

| Low income | 192.9 | 164.1 | 268.7 | 368.9 | 650.0 | 224.8 | 241.9 | 85.1 | 102.3 | 167.8 | 152.5 | 79.1 |

| Low and middle income | 140.7 | 90.1 | 192.5 | 357.1 | 700.4 | 396.3 | 363.9 | 64.0 | 98.0 | 88.3 | 98.1 | 69.7 |

| Lower middle income | 154.2 | 105.0 | 218.3 | 429.3 | 656.6 | 408.8 | 300.8 | 68.1 | 89.9 | 94.4 | 142.7 | 92.5 |

| Middle income | 137.2 | 82.6 | 189.7 | 355.7 | 700.4 | 430.5 | 369.2 | 60.2 | 96.1 | 79.4 | 96.4 | 70.2 |

| Upper middle income | 124.0 | 59.8 | 173.1 | 299.6 | 716.8 | 501.2 | 414.2 | 48.2 | 94.6 | 56.6 | 72.3 | 58.3 |

| High income | 123.6 | 61.3 | 127.3 | 165.9 | 265.5 | 270.5 | 208.6 | 49.6 | 82.7 | 50.7 | 79.5 | 64.3 |

References

- Simonis, U.E. Beyond Growth: Elements of Sustainable Development; Edition Sigma: Berlin, Germany, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, B. Produktywność zasobów w rolnictwie w Polsce wobec paradygmatu zrównoważonego rozwoju (Resource Productivity in Polish Agriculture: Towards the Paradigm of Sustainable). Stud. Ekon. 2012, 2, 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Uziak, J.; Lorencowicz, E. Sustainable Agriculture–Developing Countries Perspective. In IX International Scientific Symposium “Farm Machinery and Processes Management in Sustainable Agriculture”; University of Life Sciences: Lublin, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, B.; Kłodowska, M.; Matuszczak, A.; Matuszewska, A.; Śmidoda, D. Social Sustainability in Agricultural Farms with Selected Types of Production in European Union Countries. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2018, 20, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinina, O.V.; Olentsova, J.A. Elements of Sustainable Development of Agricultural Enterprises. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 421, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. 2025. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Kołodziejczak, W. Employment and Gross Value Added in Agriculture Versus Other Sectors of the European Union Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, F. The National System of Political Economy; Longmans, Green Co.: London, UK, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A.G.B. Production, Primary, Secondary and Tertiary. Econ. Rec. 1939, 15, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourastié, J. Die Grosse Hoffnung des Zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts (The Great Hope of the 20th Century); Bund-Verlag: Köln-Deutz, Germany, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C. The Conditions of Economic Progress; MacMillan, St. Martin’s Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Drejerska, N. Przemiany Sektorowej Struktury Zatrudnienia Ludności Wiejskiej (Changes in the Sectoral Employment Structure of the Rural Population); Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejczak, M. Zmieniająca Się Natura Usług. Studium Usług Produkcyjnych w Rolnictwie Krajów Unii Europejskiej (The Changing Nature of Services. A Case Study of Production Services in Agriculture in EU Member Countries); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Kraków, Poznań, 2019; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.P.; Palacio, A. Structural Change and Income Inequality—Agricultural Development and inter-sectoral Dualism in the Developing World, 1960–2010. OASIS 2015, 23, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsushi, S.I.; Bilal, M. Asia’s Rural-Urban Disparity in the Context of Growing Inequality; 27 IFAD Research Series; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Data Catalog. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Kolodziejczak, W. Labour Productivity and Employment in Agriculture in the European Union. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2025, XXVIII, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025. 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- European Commission. Poverty and Social Exclusion in Rural Areas: Final Report. DG Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=2085&langId=en&utm_source (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Decent Work Deficits Among Rural Workers. 2022. Available online: www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_dialogue/%40actrav/documents/publication/wcms_850582.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- White, B. Agriculture and the Generation Problem; Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series the Open Access ICAS Small eBook Book Series; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2020; Available online: https://pure.eur.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/56253917/Agriculture_and_the_Generation_Problem.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Wu, X.; Qi, X.; Yang, S.; Ye, C.; Sun, B. Research on the Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty in Rural China Based on Sustainable Livelihood Analysis Framework: A Case Study of Six Poverty-Stricken Counties. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichsteller, M.; Njagi, T.; Nyukuri, N. The role of agriculture in poverty escapes in Kenya–Developing a capabilities approach in the context of climate change. World Dev. 2022, 149, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, P.; Leach, L.S.; Strazdins, L.; Olesen, S.C.; Rodgers, B.; Broom, D.H. The psychosocial quality of work determines whether employment has benefits for mental health: Results from a longitudinal national household panel survey. BMJ J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 68, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Environmental regulation and high-quality agricultural development. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA. Sustainable Agricultural Productivity Growth: What, Why and How. 2025. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/staff-offices/office-chief-economist/sustainability/sustainable-productivity-growth-coalition/sustainable-agricultural-productivity-growth-what-why-and-how (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9a0fca06-5c5b-4bd5-89eb-5dbec0f27274/content (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Fuglie, K.; Gautam, M.; Goyal, A.; Maloney, W.F. Harvesting Prosperity: Technology and Productivity Growth in Agriculture. World Bank Group, 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/750a202b-825d-5c26-94c3-2d04aa170973/content (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Valin, H.; Hertel, T.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Hasegawa, T.; Stehfest, E. Achieving Zero Hunger by 2030 A Review of Quantitative Assessments of Synergies and Tradeoffs Amongst the UN Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations Food Systems Summit 26 May 2021. Available online: https://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SDG2_Synergies_and_tradeoffs.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Introduction to Book IV; Metalibri: Amsterdam, The Netherland; Lausanne, Switzerland; Melbourne, Australia; Milan, Italy; New York, NY, USA; Sao Paulo, Brasil, 2007; Available online: https://www.ibiblio.org/ml/libri/s/SmithA_WealthNations_p.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Marx, K. Capital Volume 1; Penguin Classics: London, UK, 1982; Available online: https://www.surplusvalue.org.au/Marxism/Capital%20-%20Vol.%201%20Penguin.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Marx, K. Theories of Surplus-Value, Part I, Chapter IV: Productive and Unproductive Labour. 1863. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value/ch04.htm (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Martínez-Castillo, R. Sustainable Agricultural Production Systems. Tecnol. Marcha 2016, 29 (Suppl. S1), 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Productivity and Efficiency Measurement in Agriculture. Literature Review and Gaps Analysis. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca6428en/ca6428en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Jialing, Y.; Jian, W. The Sustainability of Agricultural Development in China: The Agriculture–Environment Nexus. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelsman, E.; Haltiwanger, J.; Scarpetta, S. Cross-Country Differences in Productivity: The Role of Allocation and Selection. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apap, W.; Gravino, D. A Sectoral Approach to Okun’s Law. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farole, T.; Ferro, E.; Gutierrez, V.M. Job Creation in the Private Sector; Jobs Working Paper; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, E.; Bürgi, C. Sectoral Okun’s Law and Cross-Country Cyclical Differences; RPF Working Paper No. 2019-002; The George Washington University, The Center for Economic Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J. Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis. Am. Econ. Rev. 1967, 57, 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, L.R.; Pissarides, C.A. Structural Change in a Multisector Model of Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Economic Development and the Decline of Agricultural Employment. In Handbook of Development Economics; Schulz, T.P., Strauss, J.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 3051–3083. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.S. Spatial Variations, Changes and Trends in Agricultural Efficiency in Uttar Pradesh, 1953–1963. Indian J. Agric. Econ. 1967, XXII, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, W.; Kołodziejczak, M. Potencjał Produkcyjny Rolnictwa Polskiego i Efektywność Gospodarowania w Aspekcie Integracji z Unią Europejską (The Production Potential of Polish Agriculture and Management Efficiency in Terms of Integration with the European Union); Akademia Rolnicza w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baležentis, T.; Tianxiang, L.; Xueli, C. Has Agricultural Labor Restructuring Improved Agricultural Labor Productivity in China? A Decomposition Approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 76, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Restuccia, D.; Santaeulàlia-Llopi, R. The Effects of Land Markets on Resource Allocation and Agricultural Productivity; Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series; Working Paper No 1011; GSE: Columbia, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. A Global Analysis of Agricultural Productivity and Water Resource Consumption Changes over Cropland Expansion Regions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 321, 107630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L. Agricultural Investment, Production Capacity and Productivity. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/x9447e/x9447e03.htm. (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Kołodziejczak, W.; Wysocki, F. Determinanty aktywności ekonomicznej ludności wiejskiej w Polsce (Determinants of Economic Activity of the Rural Population in Poland); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heyneman, S.P. Improving the Quality of Education in Developing Countries. Financ. Dev. 1983, 20, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A.D. Education and Agricultural Development in the Caribbean: The Case of Barbados. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 1995, 15, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porceddu, E.; Rabbinge, R. Role of research and education in the development of agriculture in Europe. Dev. Crop Sci. 1997, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, L. From Agriculture Education for Rural Development and Food Security: All for Education and Food for All. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Higher Agricultural Education, Plymouth, UK, 10–13 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, F.; Alexandre, R.; Diman, C.; Alexandre, G.; Diman, J.L.; Archimede, H. A participatory approach in agricultural development: A Case Study of a Research-Education-Development Project to Optimise Mixed Farming Systems in Guadeloupe (FWI). Adv. Anim. Biosci. 2010, 1, 507–508. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, A.S. Rural Education As Rural Development: Understanding the Rural School–Community Well-Being Linkage in a 21st-Century Policy Context. Peabody J. Educ. 2016, 91, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Moulton, J. Improving Education in Rural Areas: Guidance for Rural Development Specialists; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://policytoolbox.iiep.unesco.org/library/45954DFT (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Christiansen, L.; Rutledge, Z.; Taylor, J.E. Viewpoint: The future of work in agri-food. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, A.; Guth, M.; Matuszczak, A.; Majchrzak, A.; Brelik, A.; Stepien, S. Socio-Economic Determinants of Small Family Farms’ Resilience in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Dercon, S.; Gollin, D.; Zeitlin, A. Agricultural productivity and structural transformation: Evidence and questions for African development. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2023, 32, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, I. Ludność, Zatrudnienie i Bezrobocie na Wsi. Dekada Przemian; IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, A. Zrównoważony Rozwój Gospodarstw Rolnych z Uwzględnieniem Wpływu Wspólnej Polityki Rolnej Unii Europejskiej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell, M. The European Model of Agriculture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, K.; Cardwell, M. The European Model of Agriculture. by Michael Cardwell. Review by: Keith Vincent 2005. Mod. Law Rev. 2005, 68, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, S.; Sobiecki, R. European Model of Agriculture in Relation to Global Challenges 2014. Zagadnienia Ekonomiki Rolnej 2011, 4, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejczak, W. Reduction of Employment as the Way to Balance Production Processes in the Polish Agriculture. In Agrarian Perspectives XXVII Food Safety-Food Security. Proceedings of the 27th International Scientific Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 19–20 September 2018; Tomšík, K., Ed.; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Economics and Management: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. A/RES/71/313. 2017. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/RES/71/313 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. SDG Indicators. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations, 2017. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Our World in Data. Sustainable Development Goal 8. Promote Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/sdgs/economic-growth (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- FADN (Committee for the Farm Accountancy Data Network). Typology Handbook. European Commission, July 2020. Available online: https://fadn.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Typology_Handbook_RICC1500rev5_202012.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- GUS. Rocznik Statystyczny Rolnictwa 2023; Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS): Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Godoy, D.; OECD. Aligning Agricultural and Rural Development Policies in the Context of Structural Change. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Paper; October 2022, 187. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/10/aligning-agricultural-and-rural-development-policies-in-the-context-of-structural-change_3b594208/1499398c-en.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Socha, M.; Sztanderska, U. Strukturalne Podstawy Bezrobocia w Polsce; Wyd. Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejczak, W.; Wysocki, F. Identyfikacja charakteru bezrobocia w Polsce w latach 2006–2009 (The Nature of Unemployment in Poland in 2006–2009). Gospod. Nar. 2013, 9, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M.; Mitra, A. Technology Adoption and Employment in Less Developed Countries: A Mixed-Method Systematic Review. World Dev. 2017, 96, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Lu, S.; Wu, G. Exploring the Impact of Rural Labor Mobility on Cultivated Land Green Utilization Efficiency: Case Study of the Karst Region of Southwest China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. The Impact of Agricultural Labor Migration on the Urban–Rural Dual Economic Structure: The Case of Liaoning Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Oxley, L.; Ma, H. What Makes Farmers Exit Farming: A Case Study of Sindh Province, Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Ji, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. The Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Farmland Production Efficiency: An Empirical Study Based in Jiangsu Province, China. Processes 2023, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Ponnusamy, S. Structural transformation away from agriculture in growing open economies. Agric. Econ. J. IAAE 2023, 54, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, J.; Dacuycuy, C.; Lanzafame, M. The Declining Share of Agricultural Employment in the People’s Republic of China: How Fast? ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 419; Asian Development Bank (ADB): Manila, Philippines, 2014; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Chapter 5 Income Protection for Farmers. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/w7440e/w7440e06.htm (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Caldarola, B.; Mazzilli, D.; Patelli, A.; Sbardella, A. Structural Change, Employment, and Inequality in Europe: An Economic Complexity Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.07906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczak, M. The Use of Agricultural Services in European Union Regions Differing in Selected Agricultural Characteristics. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, V. The impact of the age structure of active population on agricultural activity rate: The case study of the Timok Krajina region. East. Eur. Countrys. 2023, 28, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, Y.; Lalley, C. Education Expansion, Income Inequality and Structural Transformation: Evidence From OECD Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 169, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotschy, R.; Suarez Urtaza, P.S.; Sunde, U. The demographic dividend is more than an education dividend. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25982–25984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Liang, H.; Shi, W. Rural Population Aging, Capital Deepening, and Agricultural Labor Productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | SDG Indicator |

|---|---|

| 8.1. Sustainable economic growth | 8.1.1. GDP per capita growth rate |

| 8.2. Diversify, innovate, and upgrade for economic productivity | 8.2.1. GDP per capita growth rate per employed person |

| 8.3. Promote policies to support job creation and growing enterprises | 8.3.1. Informal employment |

| 8.4. Improve resource efficiency in consumption and production | 8.4.1. Material footprint 8.4.2. Domestic material consumption |

| 8.5. Full employment and decent work with equal pay | 8.5.1. Hourly earnings 8.5.2. Unemployment rate |

| 8.6. Promote youth employment, education, and training | 8.6.1. Youth employment, education, and training |

| 8.7. End modern slavery, trafficking, and child labour | 8.7.1. Child labour |

| 8.8. Protect labour rights and promote safe working environments | 8.8.1. Occupational injuries 8.8.2. Compliance with labour rights |

| 8.9. Promote beneficial and sustainable tourism | 8.9.1. Tourism contribution to GDP |

| 8.10. Universal access to banking, insurance, and financial services | 8.10.1. Access to financial services 8.10.2. Population with financial accounts |

| 8.a. Increase aid for trade support | 8.a.1. Aid for Trade |

| 8.b. Develop a global youth employment strategy | 8.b.1. Youth employment strategy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kołodziejczak, W. Proposal for a New Indicator of the Economic Dimension of Sustainable Development: The Unproductive Employment Rate (UER). Sustainability 2025, 17, 10711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310711

Kołodziejczak W. Proposal for a New Indicator of the Economic Dimension of Sustainable Development: The Unproductive Employment Rate (UER). Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310711

Chicago/Turabian StyleKołodziejczak, Włodzimierz. 2025. "Proposal for a New Indicator of the Economic Dimension of Sustainable Development: The Unproductive Employment Rate (UER)" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310711

APA StyleKołodziejczak, W. (2025). Proposal for a New Indicator of the Economic Dimension of Sustainable Development: The Unproductive Employment Rate (UER). Sustainability, 17(23), 10711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310711