How Does Digital Economy Drive High-Quality Agricultural Development?—Based on a Dynamic QCA and NCA Combined Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Model Construction

2.1. Theoretical Logic and Interaction Mechanisms Within the TOE Framework

2.2. Interdimensional Linkages Within the TOE Framework

- (1)

- From Technology to Organization (T → O): Robust digital infrastructure (T) generates vast amounts of agricultural data [50]. To harness this data, organizations must invest in digital resources (O), such as data analytics platforms and skilled personnel (a subset of DTT), and develop digital government systems (O) to manage and regulate data flows. Thus, technology necessitates organizational adaptation and investment.

- (2)

- From Organization to Environment (O → E): Organizational investments in digital resources (O) and effective digital governance (O) create a stable and predictable market environment, which attracts and spurs the growth of digital finance (E) and the digital industry (E) [51]. For instance, clear government data standards (O) can incentivize fintech companies to devise tailored agricultural credit products (E).

- (3)

- Direct and Feedback Effects: While the T → O → E chain is central, direct effects (e.g., technology directly reducing transaction costs in the environment) and feedback effects are also recognized [52]. Our configurational approach is well suited to capture these complex, non-linear interdependencies.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Method

3.1.1. NCA and Dynamic QCA Method

- (1)

- Sequential Integration: First, we use NCA to rigorously test whether any single digital economy element is an indispensable (necessary) condition for high AGTFP. A finding of “no single necessary condition” validates the core QCA premise of causal complexity and equifinality, justifying the subsequent search for multiple sufficient configurations. Then, dynamic QCA is applied to uncover these distinct, viable pathways and to track their evolution from 2011 to 2023.

- (2)

- Interpreting Seemingly Contradictory Results: It is crucial to anticipate and explain the potential for seemingly contradictory results between the two methods, as they test different types of causal relationships. For example, a condition may be identified by QCA as a core component of one or several sufficient configurations without being a necessary condition for the entire sample when tested by NCA. This is not a methodological inconsistency but a substantive finding that underscores causal complexity. For instance, if digital finance is identified as a core condition in several pathways by QCA but not as a necessary condition by NCA, it should be interpreted as being a critical enabler in specific contexts, but not a universal “show-stopper”. Our integrated framework is uniquely positioned to capture and make sense of this nuance.

3.1.2. SBM-GML Model

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. Outcome Variable

3.2.2. Condition Variables

3.2.3. Data Calibration

4. Data Analysis and Empirical Results

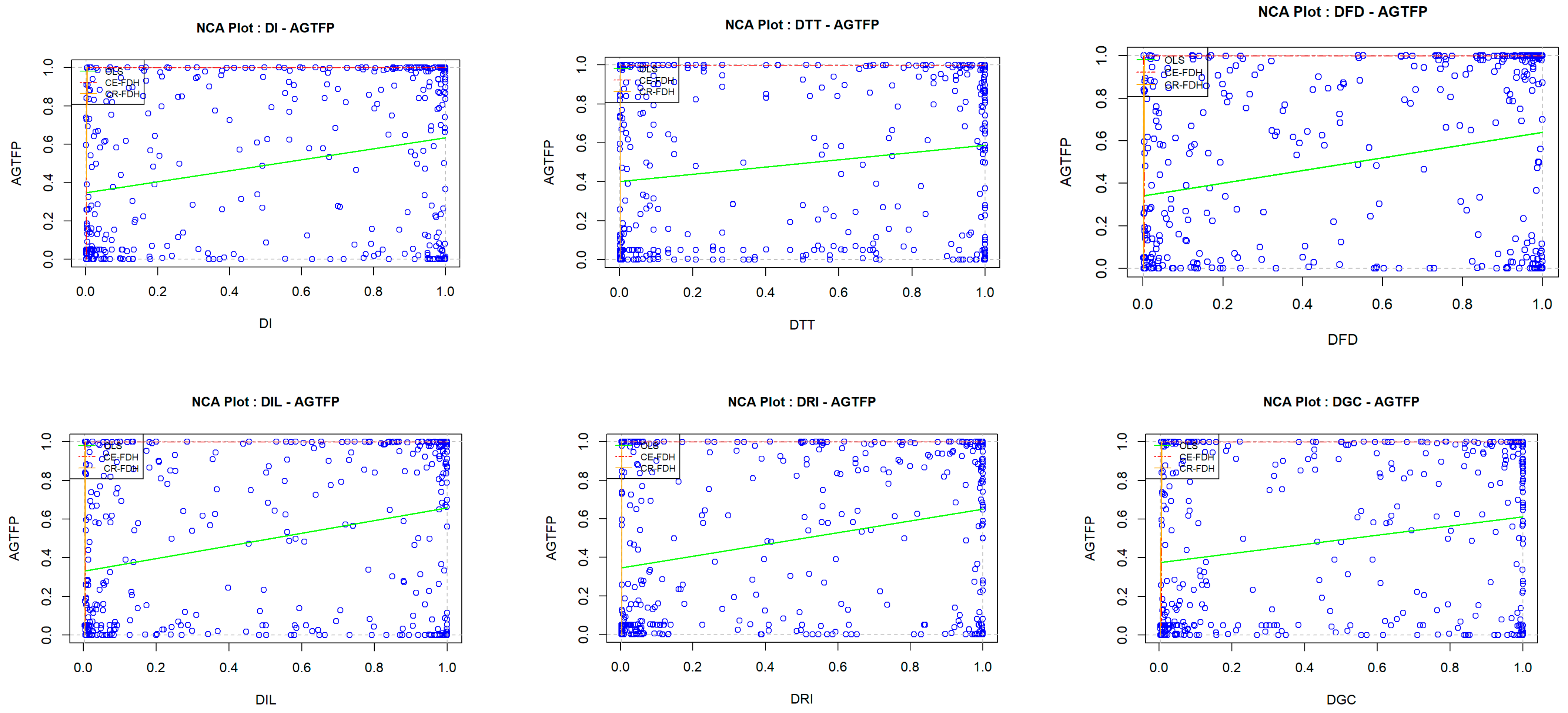

4.1. Necessary Condition Analysis

4.2. Analysis of Single-Condition Necessity

4.3. Analysis of Sufficiency for Condition Configurations

4.3.1. Summary of Results Analysis

- (1)

- Configuration Analysis of High-Quality Agricultural Development

- (2)

- Configuration Analysis of Low-Quality Agricultural Development

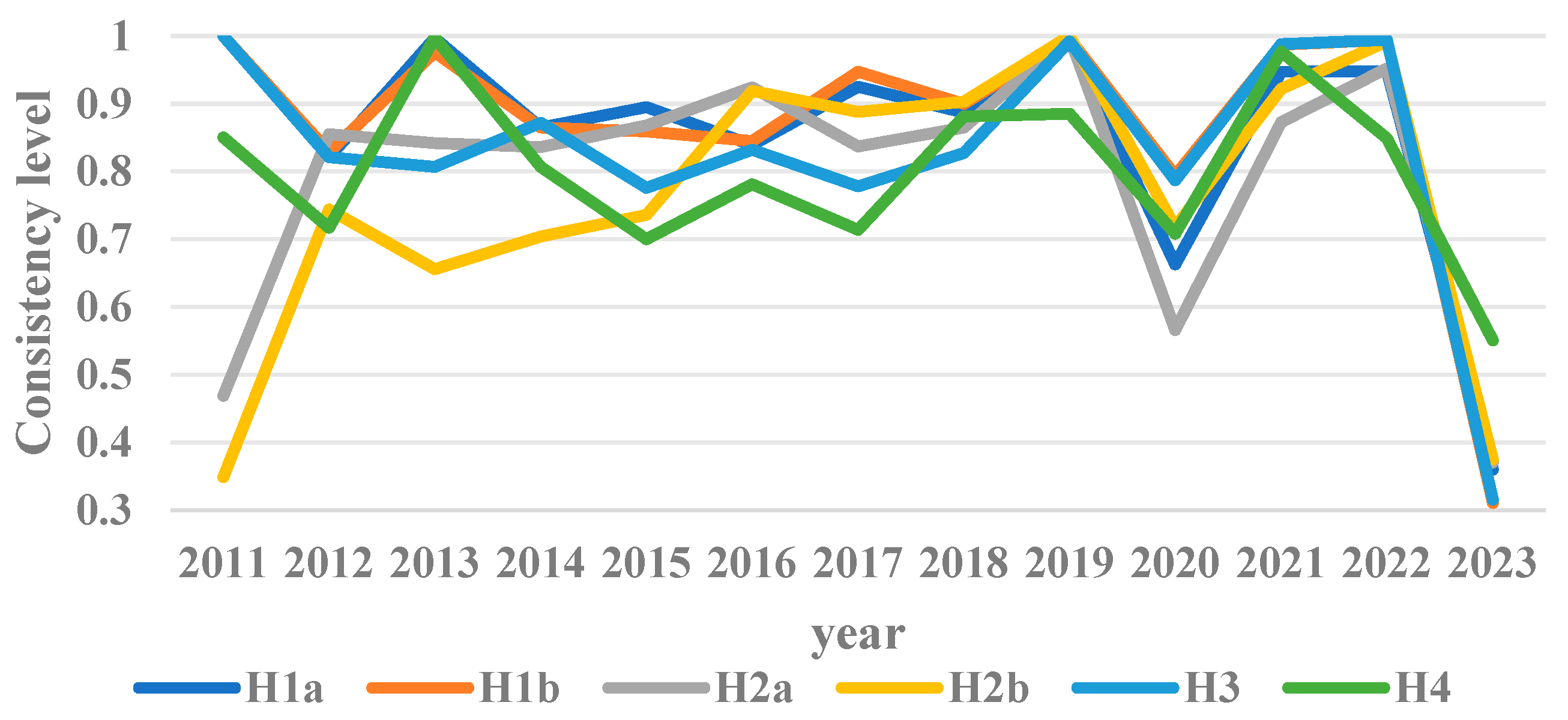

4.3.2. Inter-Group Consistency Analysis

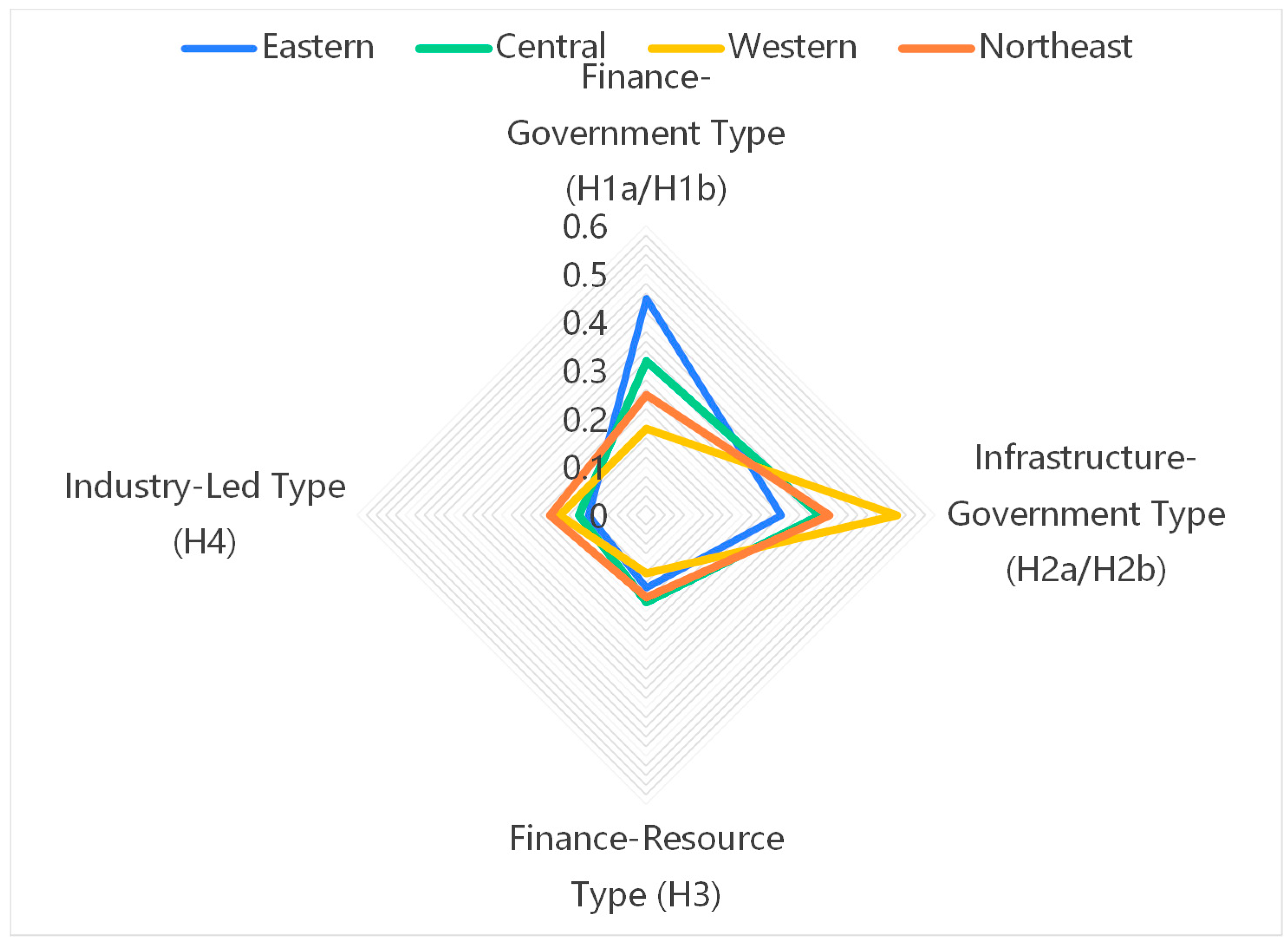

4.3.3. Regional Differences Analysis of High-Quality Agricultural Development Pathways

4.4. Robustness Test

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusion

5.2. Theoretical Significance

5.3. Practical Significance

- (1)

- Differentiated Regional Strategies Based on Path Characteristics

- (2)

- Differentiated Evaluation Mechanisms Based on Path Characteristics

- (3)

- Differentiated Talent Development Mechanisms

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, J.; Qiao, C. Digital economy and high-quality agricultural development: Mechanisms of technological innovation and spatial spillover effects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, H. Research on the impact and mechanism of digital economy on China’s food production capacity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Dai, X.; Luo, Y. The effect of farmland transfer on agricultural green total factor productivity: Evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhuang, J.; Sun, Z.; Huang, M. How can rural digitalization improve agricultural green total factor productivity: Empirical evidence from counties in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y. The impact of the digital economy on high-quality agricultural development—Based on the regulatory effects of financial development. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. How does the digital economy impact the high-quality development of agriculture? An empirical test based on the spatial Durbin model. Digit. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Kong, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, B. Can the digital economy reduce the rural-urban income gap? Sustainability 2024, 16, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Tian, M.; Wang, J. The impact of digital economy on green development of agriculture and its spatial spillover effect. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Qin, R.; Lei, S.; Tang, Y. Influence of data elements on China’s agricultural green total factor productivity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, L. Impact of Digital Economy on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of the “Broadband China” Strategy. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1607567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, J.; Song, J.; Chen, X. Digital agriculture’s impact on carbon dioxide emissions varies with the economic development of Chinese provinces. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Fang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Research on the Impact of the Integration of Digital Economy and Real Economy on Enterprise Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L. Digital economy and high-quality agricultural development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 99, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. The impact mechanism of digital rural construction on land use efficiency: Evidence from 255 cities in China. Sustainability 2024, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wei, W.; Ge, W.; Liu, S.; Chou, Y. Digital Technology and Agricultural Production Agglomeration: Mechanisms, Spatial Spillovers, and Heterogeneous Effects in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Yao, D. The impact of digital transformation on supply chain capabilities and supply chain competitive performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wan, J.; Dai, Z. How does digital technology application empower specialty agricultural farmers? Evidence from Chinese litchi farmers. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1444192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, D. Optimizing digital transformation paths for industrial clusters: Insights from a simulation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, K. The impact of the digital economy on industrial structure upgrading in resource-based cities: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, L.; Kang, X. Digital inclusive finance and agricultural green development in China: A panel analysis (2013–2022). Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Digital finance and agricultural green total factor productivity: Evidence from China. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 76, 214–229. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Zhong, Z. Impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural total factor productivity in Zhejiang Province from the perspective of integrated development of rural industries. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhlanga, D.; Ndhlovu, E. Digital Technology Adoption in the Agriculture Sector: Challenges and Complexities in Africa. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 2023, 6951879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, K.; Deng, X. Can internet use promote farmers’ diversity in green production technology adoption? Empirical evidence from rural China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Guo, C. Digital Inclusive Finance and the Construction of Agricultural Modernization. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liao, H.; Han, G.; Liu, Y. The impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural green total factor productivity: A study based on China’s provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePietro, R.; Wiarda, E.; Fleischer, M. The context for change: Organization, technology and environment. Process. Technol. Innov. 1990, 199, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Dong, S.; Xu, S.X.; Kraemer, K.L. Innovation diffusion in global contexts: Determinants of post-adoption digital transformation of European companies. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Q.A.; Zhang, H.; Chen, P.; Chen, S. A study on the influencing factors of corporate digital transformation: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, S.P.; Han, Z.M. Agricultural digitalization and the development of new-type agricultural management entities. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2023, 5, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, A.; Tumiwa, J.; Arie, F.; László, E.; Alsoud, A.R.; Al-Dalahmeh, M. A meta-analysis of the impact of TOE adoption on smart agriculture SMEs performance. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, R.; Jing, W.; Liu, Z.; Tang, A. Development of China’s Digital Economy: Path, Advantages and Problems. J. Internet Digit. Econ. 2024, 4, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Y.; Xu, Q. Design of an intelligent greenhouse water-saving irrigation control system. Mod. Agric. Equip. 2022, 43, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.F.; Zhao, Q.F.; Zhang, L.X. The theoretical framework, efficiency-enhancing mechanism and realization path of digital technology empowering high-quality agricultural development. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Daum, T. Digitalization and skills in agriculture. Outlook Agric. 2025, 54, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wei, F. Digital Infrastructure and Agricultural Global Value Chain Participation: Impacts on Export Value-Added. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lou, W. Digital Government Construction and Provincial Green Innovation Efficiency: Empirical Analysis Based on Institutional Environment in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yang, X.; Ren, J.; Yin, C. Towards digital transformation of agriculture for sustainable development in China: Experience and lessons learned. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, D. Digital transformation in rural governance: Unraveling the micro-mechanisms and the role of government subsidies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liao, F.; Tian, M. Examining the Factors Influencing the Digital Transformation of New Agricultural Operating Entities: Insights from Zhejiang, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Min, J.; Meng, S.; Dai, W.; Li, X. Can digital governance stimulate green development? Evidence from the program of “pilot cities regarding information for public well-being” in China. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1463532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finger, R. Digital innovations for sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 50, 1277–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, N. The impact of digital inclusive finance on the agricultural factor mismatch of agriculture-related enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Digital Inclusive Finance Harvest: Cultivating Creditworthiness for Small Agricultural Businesses. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2025, 91, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R. Can digitally-enabled financial instruments secure an inclusive agricultural transformation? Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choruma, D.J.; Dirwai, T.L.; Mutenje, M.J.; Mustafa, M.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Jacobs-Mata, I.; Mabhaudhi, T. Digitalisation in agriculture: A scoping review of technologies in practice, challenges, and opportunities for smallholder farmers in sub-saharan africa. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvagerd, M.; Mayer, M.; Hartmann, M. Digital platforms in the agricultural sector. Big Data Soc. 2024, 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.; Deng, X.; Lu, H.; Niu, L. Configurational Pathways to Breakthrough Innovation in the Digital Age: Evidence from Niche Leaders. Systems 2024, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Le, X.C.; Vu, T.H.L. An Extended Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework for Online Retailing Utilization in Digital Transformation: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, F. What drives the development of digital rural life in China? Heliyon 2024, 10, e39511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindeeba, D.S.; Tukamushaba, E.K.; Bakashaba, R. How digital capabilities and credit access influence green innovation performance in small and medium enterprises in resource constrained settings. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, F.; Le, V.; Masli, E.K. Determinants of digital technology adoption in innovative SMEs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Identifying single necessary conditions with NCA and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Fuzzy-Set Social Science; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Verweij, S.; Vis, B. Three strategies to track configurations over time with Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2021, 13, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. Understanding the green total factor productivity of manufacturing industry in China: Analysis based on the super-SBM model with undesirable outputs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Duan, J.; Geng, S.; Li, R. Spatial network and driving factors of agricultural green total factor productivity in China. Energies 2023, 16, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Guojia, H. Measurement and temporal–spatial comparison of the integration of the digital economy and the real economy in the context of new quality productivity: Based on the patent co-classification method. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2024, 41, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, M.; Zheng, X. Digital economy, agricultural technology innovation, and agricultural green total factor productivity. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231194388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, M.H.; Huber, R.; Finger, R. Agricultural policy in the era of digitalisation. Food Policy 2021, 100, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.W.; Tang, C. Impact of digital economy development on agricultural carbon emissions and its temporal and spatial effects. Sci. Tochnol. Manag. Res. 2023, 43, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Su, K.; Wang, S. Evaluation of digital economy development level based on multi-attribute decision theory. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Witt, M.A.; Aguilera, R.V.; Verbeke, A. The contributions of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, T.C.; Federo, R. Qualitative comparative analysis: Justifying a neo-configurational approach in management research. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Liu, Q.C.; Chen, K.W.; Xiao, R.Q.; Li, S.S. Robustness test of business environment configurations for high total factor productivity: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis approach. Manag. World 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Mensah, C.N.; Lu, Z.; Wu, C. Environmental regulation and green total factor productivity in China: A perspective of Porter’s and Compliance Hypothesis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, S.; Xie, F. Green Finance and Green Total Factor Productivity: Impact Mechanisms, Threshold Characteristics, and Spatial Effects. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251345879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Antecedent Condition | Measurement Indicator | Indicator Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological conditions | DI [58] | Internet penetration rate | Number of Internet users/total population | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Broadband access rate | Number of broadband Internet subscribers/total population | China Communication Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Number of broadband ports | Direct data | China Communication Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Length of long-distance optical cable lines | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| DTT | Number of employees in information transmission, software, and IT services | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| Organizational conditions | DRI [59] | Education expenditure | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Science and technology expenditure | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| R&D investment | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| DGD [60] | GDP per capita | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | |

| Number of industrial enterprises above designated size | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Total foreign enterprise investment | Regional GDP/total resident population | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Total retail sales of consumer goods | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Environmental conditions | DFD [61] | Digital Inclusive Finance Index | Direct data | Peking University Digital Finance Research Center [61] |

| DID [62] | Per capita telecommunications business volume | Total telecommunications business volume/total population | China Communication Statistical Yearbook | |

| Mobile phone penetration rate | Number of mobile phone users/total population | China Communication Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Number of legal entities in information transmission, software, and IT services | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| E-commerce sales | Direct data | China Statistical Yearbook | ||

| Share of enterprises engaged in e-commerce transactions | Number of enterprises with e-commerce activities/total enterprises | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Variable Type | Calibration Anchors | Descriptive Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Membership | Crossover Point | Full Non-Membership | Mean | SD | Min | Max | ||

| Outcome variable | AGTFP | 1.083 | 1.034 | 1.000 | 1.038 | 0.154 | 0.415 | 1.782 |

| Antecedent conditions | DI | 0.447 | 0.344 | 0.231 | 0.346 | 0.152 | 0.466 | 0.768 |

| DTT | 13.450 | 6.600 | 4.400 | 12.878 | 17.441 | 0.200 | 107.400 | |

| DFD | 340.735 | 267.800 | 173.190 | 253.511 | 110.701 | 16.220 | 498.280 | |

| DID | 0.215 | 0.112 | 0.061 | 0.154 | 0.132 | 0.008 | 0.720 | |

| DRI | 0.179 | 0.083 | 0.043 | 0.136 | 0.154 | 0.001 | 0.936 | |

| DGD | 0.157 | 0.089 | 0.044 | 0.119 | 0.108 | 0.002 | 0.571 | |

| Condition | Method | Accuracy (%) | Ceiling Zone | Scope | Effect Size (d) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DI | CR | 98.5% | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| DTT | CR | 99.5% | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.235 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.109 | |

| DFD | CR | 97.3% | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| CE | 100% | 0.002 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | |

| DID | CR | 99.3% | 0.001 | 0.997 | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| CE | 100% | 0.002 | 0.997 | 0.002 | 0.000 | |

| DRI | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.146 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.006 | |

| DGD | CR | 99.5% | 0.002 | 0.997 | 0.002 | 0.014 |

| CE | 100% | 0.003 | 0.997 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Y | DI | DTT | DFD | DID | DRI | DGD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN | NN | 0.0 | 0.0 | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 20 | NN | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 30 | NN | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 40 | NN | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 50 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 60 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 70 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 80 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 90 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 100 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Condition Variable | Y (High AGTFP) | ~Y (Low AGTFP) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Consistency | Overall Coverage | Inter-Group Consistency- Adjusted Distance | Intra-Group Consistency- Adjusted Distance | Overall Consistency | Overall Coverage | Inter-Group Consistency- Adjusted Distance | Intra-Group Consistency- Adjusted Distance | |

| DI | 0.649 | 0.635 | 0.555 | 0.350 | 0.448 | 0.454 | 0.727 | 0.426 |

| ~DI | 0.442 | 0.436 | 0.671 | 0.449 | 0.639 | 0.654 | 0.667 | 0.280 |

| DTT | 0.586 | 0.600 | 0.141 | 0.788 | 0.455 | 0.483 | 0.181 | 0.805 |

| ~DTT | 0.496 | 0.467 | 0.358 | 0.776 | 0.623 | 0.609 | 0.153 | 0.642 |

| DFD | 0.657 | 0.640 | 0.768 | 0.193 | 0.453 | 0.458 | 0.804 | 0.268 |

| ~DFD | 0.443 | 0.439 | 0.788 | 0.292 | 0.643 | 0.660 | 0.776 | 0.198 |

| DID | 0.648 | 0.650 | 0.559 | 0.333 | 0.424 | 0.441 | 0.687 | 0.566 |

| ~DID | 0.443 | 0.426 | 0.647 | 0.473 | 0.664 | 0.661 | 0.575 | 0.350 |

| DRI | 0.638 | 0.653 | 0.137 | 0.695 | 0.425 | 0.450 | 0.257 | 0.782 |

| ~DRI | 0.463 | 0.437 | 0.382 | 0.735 | 0.673 | 0.658 | 0.197 | 0.572 |

| DGD | 0.620 | 0.623 | 0.149 | 0.695 | 0.453 | 0.471 | 0.273 | 0.759 |

| ~DGD | 0.473 | 0.455 | 0.354 | 0.724 | 0.638 | 0.635 | 0.245 | 0.607 |

| Causal Combination | Indicator | Year | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||

| Case 1 ~DTT- AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.99 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.04 | |

| Case 2 DIL- AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 1.00 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.19 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.03 | |

| Case 3 ~DRI- AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.95 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.85 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.05 | |

| Case 4 ~DGD- AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.86 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.06 | |

| Case 5 DRI- ~AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.434 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.99 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.99 | |

| Case 6 DGD- ~AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.72 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.98 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 1.00 | |

| Case 7 ~DGD- ~AGTFP | Inter-group Consistency | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.29 |

| Inter-group Coverage | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.47 | 0.98 | |

| Condition Variable | High AGTFP | Low AGTFP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial– Government Dual-Driver | Infrastructure– Government Dual-Driver | Financial–Resource Dual-Driver | Industry-Led Driver | Talent Island Trap | |||

| H1a | H1b | H2a | H2b | H3 | H4 | NH1 | |

| DI | U | U | ● | ● | U | U | U |

| DTT | U | U | ● | ● | U | ● | |

| DFD | ● | ● | U | U | ● | U | U |

| DID | ● | U | ● | ● | U | ||

| DRI | ● | ● | ● | U | U | ||

| DGD | ● | ● | ● | ● | U | U | |

| Consistency | 0.869 | 0.895 | 0.846 | 0.801 | 0.843 | 0.801 | 0.806 |

| PRI | 0.74 | 0.784 | 0.663 | 0.626 | 0.726 | 0.625 | 0.679 |

| Coverage | 0.285 | 0.287 | 0.210 | 0.352 | 0.297 | 0.292 | 0.250 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.036 | 0.021 | 0.038 | 0.250 |

| Intergroup consistency adjusted distance | 0.217 | 0.225 | 0.261 | 0.297 | 0.229 | 0.165 | 0.342 |

| Intragroup consistency adjusted distance | 0.351 | 0.294 | 0.290 | 0.328 | 0.293 | 0.257 | 0.293 |

| Overall Consistency | 0.843 | 0.806 | |||||

| Overall PRI | 0.645 | 0.679 | |||||

| Overall Coverage | 0.424 | 0.250 | |||||

| Condition Variable | High Configuration Analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | |

| DI | U | ● |

| DTT | U | ● |

| DFD | ● | U |

| DID | ● | U |

| DRI | ● | ● |

| DGD | ● | |

| Consistency | 0.895 | 0.856 |

| PRI | 0.795 | 0.672 |

| Coverage | 0.294 | 0.306 |

| Overall consistency | 0.871 | |

| Overall PRI | 0.744 | |

| Overall Coverage | 0.36 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Li, B. How Does Digital Economy Drive High-Quality Agricultural Development?—Based on a Dynamic QCA and NCA Combined Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310683

Liu Z, Li B. How Does Digital Economy Drive High-Quality Agricultural Development?—Based on a Dynamic QCA and NCA Combined Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310683

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zihang, and Bingjun Li. 2025. "How Does Digital Economy Drive High-Quality Agricultural Development?—Based on a Dynamic QCA and NCA Combined Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310683

APA StyleLiu, Z., & Li, B. (2025). How Does Digital Economy Drive High-Quality Agricultural Development?—Based on a Dynamic QCA and NCA Combined Approach. Sustainability, 17(23), 10683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310683