Can Rural Entrepreneurship Promote the Development of New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture?—Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Rural Entrepreneurial Activities and New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture

2.2. The Role of Agricultural Technological Innovation

2.3. The Roles of Rural Industrial Integration

2.4. Spatial Spillover Effects of Rural Entrepreneurship on New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Specification

3.1.1. Benchmark Regression Model

3.1.2. Panel Threshold Model

3.1.3. Spatial Durbin Model

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2.1. Rural Entrepreneurship

3.2.2. New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture

3.2.3. Agricultural Technological Innovation

3.2.4. Rural Industrial Integration

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Hypothesis Testing on the Impact of Rural Entrepreneurship on New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture

4.2. Testing the Mediating Effects of Agricultural Technological Innovation and Rural Industrial Integration

4.3. Hypothesis Testing of Threshold Effects in Agricultural Technological Innovation and Rural Industrial Integration

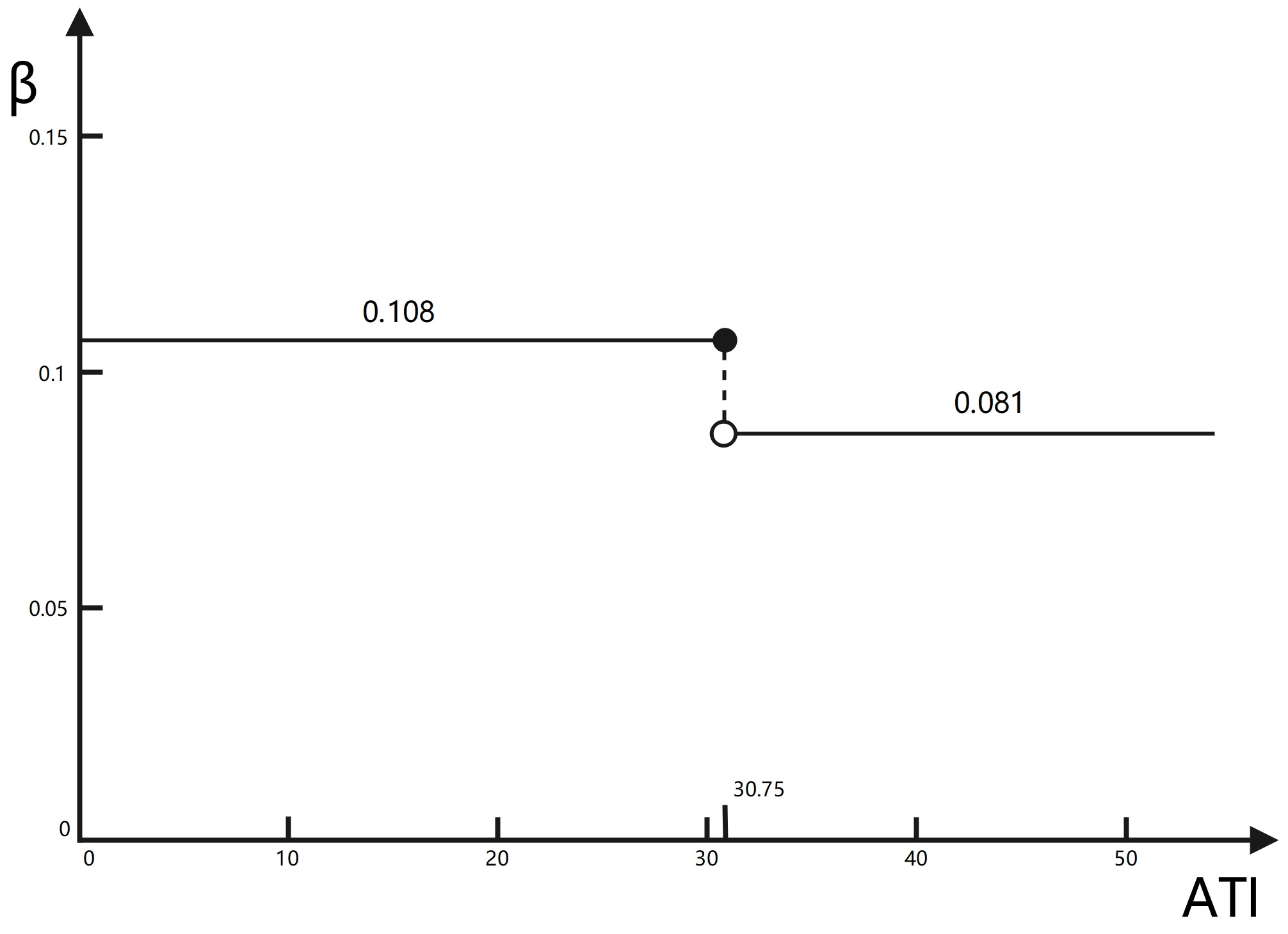

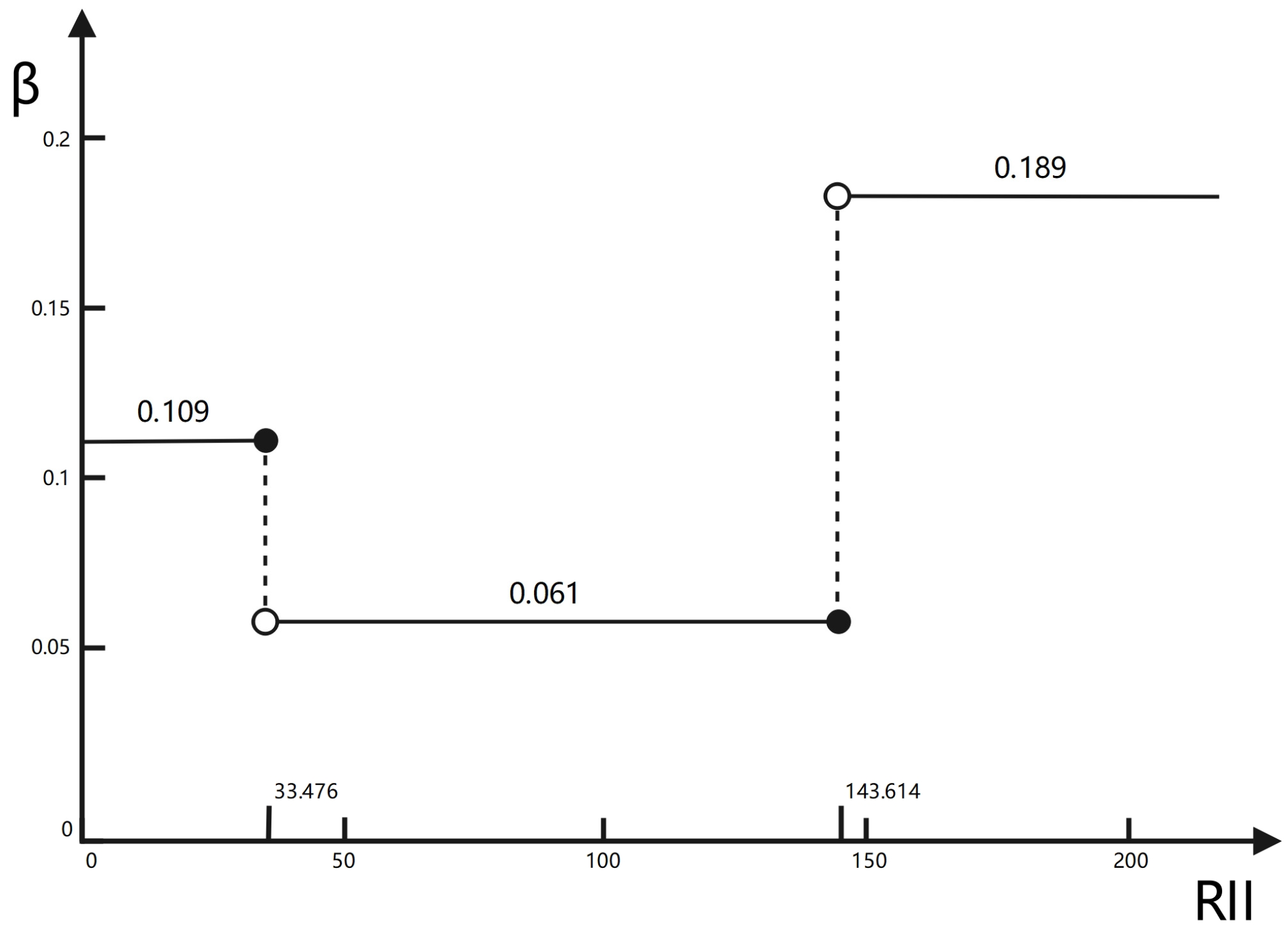

4.4. Test of Spatial Spillover Effects of Rural Entrepreneurship on New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture

4.5. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Discussion and Conclusions

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Long, S.B.; Zhang, M.X. Re-measurement and influencing factors of China’s agricultural total factor productivity—Moving from traditional to high-quality development. Res. Financ. Issues 2021, 10, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.F.; Zhao, Q.F.; Zhang, L.Y. Theoretical framework, efficiency enhancement mechanism and realization path of high-quality development of agriculture empowered by digital technology. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Lyu, X. Agricultural total factor productivity, digital economy and agricultural high-quality development. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Zeng, Z.Q.; Li, G.D. Measuring the level of high-quality development of China’s agricultural economy and its spatial variation analysis. World Agric. 2022, 4, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Regional Governments and Opportunity Entrepreneurship in Underdeveloped Institutional Environments: An Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Perspective. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-Koch, S.; Nordqvist, M.; Carter, S.; Hunter, E. Entrepreneurship in the Agricultural Sector: A Literature Review and Future Research Opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kademani, S.B.; Nain, M.S.; Mishra, J.R.; Singh, R. Policy and Institutional Support for Agri- Entrepreneurship Development in India: A Review. J. Ext. Syst. 2020, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohns, F.; Revilla, D.J. Explaining micro entrepreneurship in rural Vietnam—A multilevel analysis. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 50, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Gu, T.; Shi, Y. The Influence of New Quality Productive Forces on High-Quality Agricultural Development in China: Mechanisms and Empirical Testing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xie, F. Can new quality productivity promote high-quality agricultural development?—An empirical study based on provincial panel data in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1601227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Zou, Y. A Study on the Impact of New Quality Productivity on the High-quality Development of Manufacturing Enterprises. Environ. Soc. Gov. 2025, 2, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, Z. Research on the Theoretical Connotation and Realization Path of New Quality Productivity. Front. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 5, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kuang, Y. Evaluation, Regional Disparities and Driving Mechanisms of High-Quality Agricultural Development in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, K.A.; Koursaros, D.; Savva, C.S. The influence of the “environmental-friendly” character through asymmetries on market crash price of risk in major stock sectors. J. Clim. Financ. 2024, 9, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Cai, T.; Deng, W.; Zheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Bao, H. Indicators for Evaluating High-Quality Agricultural Development: Empirical Study from Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 1101–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zha, H. On the Measurement and Improvement Strategies of New Quality Productivity in Chinese Rural Areas. Front. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 5, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Cao, K.; Shen, Y. Construction, Index Measurement, and Promotion Strategies of Agricultural New-Quality Productivity Development System under the Perspective of Urban-Rural Integrated Development. Front. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2025, 2, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, F.G.M.; Nejad, A.H. Opportunities and Challenges of Rural Entrepreneurship in Afghanistan. J. Entrep. Bus. Divers. 2023, 1, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipo, D.T.; Lily, J.; Fabeil, N.F.; Jamil, I.A.A. Transforming Rural Entrepreneurship Through Digital Innovation: A Review on Opportunities, Barriers and Challenges. J. Manag. Sustain. 2024, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, U.; Kumar Dwivedi, A. Manifestations of rural entrepreneurship: The journey so far and future pathways. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 71, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Müller, S.; Tanvig, H.W. Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural—Between place and space. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2015, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, F.; Hao, R.; Wu, L. Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation, Spatial Spillover and Agricultural Green Development—Taking 30 Provinces in China as the Research Object. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, S. Measurement and evaluation of agricultural technological innovation efficiency in the Yellow River Basin of China under water resource constraints. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modjo, A.S.; Tapi, T.; Safruddin, S.; Ansar, M.u.h.; Fitriani, D. Harnessing Technology for Agricultural Sustainability: Case Studies and Future Directions. Join: J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-T.; Shahreki, J.; Hong, P.V.; Tung, N.V. Rural entrepreneurship in Vietnam: Identification of facilitators and barriers. Rural. Entrep. Innov. Digit. Era 2021, 1, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, X. The Impact of Technological Innovations on Agricultural Productivity and Environmental Sustainability in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Jiang, K.; Xu, C.; Yang, X. Industrial clustering, income and inequality in rural China. World Dev. 2022, 154, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yang, X.; Long, H.; Zhang, F.; Xin, Q. The Sustainable Rural Industrial Development under Entrepreneurship and Deep Learning from Digital Empowerment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, H.; Bai, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, G.; Shen, Q. Can the Integration of Rural Industries Help Strengthen China’s Agricultural Economic Resilience? Agriculture 2023, 13, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, L.; Chen, J.; Deng, X. Impact of rural industrial integration on farmers’ income: Evidence from agricultural counties in China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 93, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Sun, X. Rural Industrial Integration and New Urbanization in China: Coupling Coordination, Spatial–Temporal Differentiation, and Driving Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Qin, S.; Nisar, N.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, T.; Wang, L. Does rural industrial integration improve agricultural productivity? Implications for sustainable food production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chi, H.; Zhang, T. Effects of Entrepreneurial Activities on Rural Revitalization: Based on Dissipative Structure Theory. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, T. Digital factors spur rural industrial integration: Mediating roles of rural entrepreneurship and agricultural innovation in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1649953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Geng, B.; Wu, B.; Liao, L. Determinants of returnees’ entrepreneurship in rural marginal China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.D.; Hui, L.W. Spatial differences in the resilience of China’s agricultural economy and identification of influencing factors. World Agric. 2022, 1, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H. Knowledge-Based Regional Economic Development: A Synthetic Review of Knowledge Spillovers, Entrepreneurship, and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Econ. Dev. Q. 2018, 32, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B.; Lehmann, E.E. The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, S.; Bengtsson, L.; Karlsson, C. Strategic entrepreneurship and knowledge spillovers: Spatial and aspatial perspectives. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.P.; Yin, K. Can the Development of Digital Inclusive Finance Enhance Rural Entrepreneurship Activity? Financ. Econ. 2023, 8, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Ye, L.X. New-Quality Productive Forces in Chinese Agriculture: Measurement and Dynamic Evolution. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Wang, H.L. Environmental Regulation, Agricultural Technological Innovation, and Agricultural Carbon Emissions. J. Hubei Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 47, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.H.; Wang, M.; Tang, Y.M. Rural Tertiary Industry Integration, Consumption of Urban and Rural Residents, and Income Disparity—Can Efficiency and Equity Be Achieved Simultaneously? Chin. Rural. Econ. 2022, 3, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.Y.; Bai, L.X. Research on the Impact of Rural Tertiary Industry Integration on Farmers’ Income in China—From the Perspective of Mediating Effects. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2023, 4, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.L. Digital Inclusive Finance, Rural Entrepreneurship, and Farmers’ Income Growth. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, C.L.; He, X.R. Construction of an Evaluation Index System, Measurement, and Regional Disparities of New-Quality Productive Forces in Chinese Agriculture. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2025, 45, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Z.; Sun, B.J.; Sun, G.B. The Impact and Pathways of the Digital Economy on Agricultural Technological Innovation in China. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2025, 45, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Y.; Cheng, C.M. The Path of Tertiary Industry Integration in the Rural Revitalization Strategy: Logical Necessity and Empirical Determination. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 11, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Size | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHCL | 330 | 6.600 | 9.910 | 8.125 | 0.564 | 8.105 |

| UL | 330 | 36.300 | 89.600 | 61.187 | 12.062 | 59.680 |

| RID | 330 | 2.085 | 337.773 | 41.358 | 24.843 | 38.366 |

| RE | 330 | 0.022 | 2.846 | 0.288 | 0.454 | 0.159 |

| ATI | 330 | 0.520 | 166.510 | 31.898 | 31.567 | 20.990 |

| RII | 330 | 9.572 | 347.682 | 90.816 | 70.371 | 64.282 |

| NQPFA | 330 | 0.062 | 0.433 | 0.162 | 0.065 | 0.151 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| RE | 0.129 *** (0.012) | 0.081 *** (0.011) |

| RHCL | —— | 0.043 *** (0.007) |

| UL | —— | 0.003 *** (0.000) |

| RI | —— | 0.000 (0.000) |

| CT | 0.125 *** (0.004) | −0.391 *** (0.054) |

| R-squared (within) | 0.268 | 0.533 |

| R-squared (between) | 0.346 | 0.386 |

| R-squared (overall) | 0.304 | 0.383 |

| F-value | 18.96 *** | 29.91 *** |

| Variable | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|

| RE | 0.064 *** (0.010) | 0.064 *** (0.008) |

| ATI | 0.001 *** (0.000) | —— |

| RII | —— | 0.005 *** (0.000) |

| RHCL | 0.036 *** (0.007) | 0.022 *** (0.019) |

| EL | 0.002 *** (0.004) | −0.006 ** (0.011) |

| RI | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| CT | −0.298 *** (0.053) | −0.142 ** (0.047) |

| R-squared (within) | 0. 594 | 0.712 |

| R-squared (between) | 0. 554 | 0.692 |

| R-squared (overall) | 0.544 | 0.696 |

| F-value | 15.71 *** | 19.45 *** |

| Variable | Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|

| RE 0 | 0.108 *** (0.016) |

| RE 1 | 0.081 ** (0.016) |

| RHCL | 0.045 * (0.021) |

| UL | 0.003 (0.001) |

| RI | 0.000 (0.000) |

| CT | −0.403 ** (0.125) |

| Variable | Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|

| RE 0 | 0.109 *** (0.010) |

| RE 1 | 0.061 *** (0.012) |

| RE 2 | 0.189 ** (0.052) |

| RHCL | 0.043 * (0.019) |

| UL | 0.002 (0.001) |

| RI | −0.000 (0.000) |

| CT | −0.361 ** (0.117) |

| Regression Coefficient | SE | z-Score | p-Value | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WX Rural Entrepreneurship | 0.659 ** | 0.247 | 2.670 | 0.008 | [0.175, 1.142] |

| Direct effect | 0.022 * | 0.009 | 2.540 | 0.011 | [0.005, 0.039] |

| Indirect effect | 0.153 * | 0.062 | 2.460 | 0.014 | [0.031, 0.275] |

| Total effect | 0.175 ** | 0.063 | 2.770 | 0.006 | [0.051, 0.299] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Zhang, K. Can Rural Entrepreneurship Promote the Development of New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture?—Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310676

Xu X, Zhang K. Can Rural Entrepreneurship Promote the Development of New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture?—Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310676

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xuejiao, and Kun Zhang. 2025. "Can Rural Entrepreneurship Promote the Development of New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture?—Evidence from China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310676

APA StyleXu, X., & Zhang, K. (2025). Can Rural Entrepreneurship Promote the Development of New-Quality Productive Forces in Agriculture?—Evidence from China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310676