1. Introduction

In the context of increasingly severe global climate change and resource constraints, promoting green and low-carbon transformation and achieving sustainable development have become shared challenges and strategic goals for countries around the world. Improving energy utilization efficiency is key to achieving the coordinated development of energy conservation, emission reduction, and economic growth. As core population, industry, and economic hubs, cities are major energy consumers and sources of carbon emissions, and their development models directly affect the progress of global ecological civilization construction. As the world’s largest energy consumer, China ascribes particular importance to exploring urban low-carbon transformation paths under the larger blueprint of the “dual carbon” goals (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality). To identify effective policy tools, the Chinese government released a list of new energy demonstration cities in 2014, aiming to promote the large-scale application and industrialization of new energy technologies such as solar, wind, and biomass energy in cities through financial subsidies, technical support, and policy guidance. This initiative is intended to optimize the energy structure and explore sustainable urban development paradigms, and it represents an important practice in advancing the green transformation of the energy system. Therefore, it is of great importance to explore the impact of the new energy demonstration city pilot policy on urban energy utilization efficiency.

With the implementation of various new energy and low-carbon city pilot policies, evaluating their policy effects has become an academic hotspot. Yi Shanyu and Yin Yuanyuan (2022) [

1], using panel data from 267 prefecture-level cities from 2005 to 2019, found that the new energy demonstration city policy can effectively attract the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) in China. Yan Jiang et al. (2024) [

2], focusing on the perspective of green innovation, found that the “campus to VAT” policy significantly improved cities’ green innovation capabilities. Peng Wang and Donghai Li (2025) [

3] used panel data from 286 prefecture-level cities from 2007 to 2021 to evaluate the impact of the “campus to VAT” policy on green total-factor productivity and found that policy effects varied across regions and urban levels. Feng Yuan and Nie Changfei (2022) [

4], focusing on the perspective of pollutant emission intensity control, found that China’s new energy demonstration city construction pilot policy had a significant negative impact on environmental pollution, especially in central and western cities and cities with low economic development levels. Huang Manyu and Yang Lu (2025) [

5] tested the carbon emission reduction effect of energy transition policies using the difference-in-differences (DID) model and also found that the new energy demonstration city policy played a significant role in carbon emission reduction. Mo Li et al. (2025) [

6] constructed a multi-dimensional evaluation system for urban ecosystem resilience and found that energy structure transformation significantly enhanced urban ecosystem resilience. Yang Ma (2025) [

7], using panel data from 217 prefecture-level cities from 2012 to 2021, found that the new energy demonstration city policy significantly promoted green growth in pilot cities.

Scholars have also extensively discussed the driving factors behind energy utilization efficiency. Yarong Shi and Bo Yang (2024) [

8] used panel data from 279 prefecture-level cities from 2011 to 2021 and adopted mediating and moderating models to verify the synergistic impact of digital finance and green finance on energy efficiency. Li Shanshan and Ma Yanqin (2024) [

9], explored carbon trading policies and found that they significantly improved urban single-factor energy productivity and total-factor energy efficiency and that their effect became more significant over time. Han Xue et al. (2024) [

10], focusing on digital innovation, found that the establishment of national big data comprehensive pilot zones played an important role in promoting sustainable energy practices and contributed to the global pursuit of harmony between humans and nature. Song Yijia et al. (2025) [

11] analyzed the mechanisms through which digital enterprises improved energy utilization efficiency based on both intra-enterprise and inter-enterprise effects and explored the formation mechanisms behind the advantages of ultra-large-scale markets. Zhuoya Ren (2025) [

12], from the perspective of green finance reform, used the DID model to evaluate the impact of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones on urban green total-factor energy efficiency.

Based on existing research, this study uses data from 293 prefecture-level cities in China from 2006 to 2023 as the research sample to empirically examine the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency. Compared with existing studies, the innovative elements of this study are as follows: firstly, we chose an innovative research perspective. Most existing studies explore the impact of a single policy on energy efficiency, while this study systematically verifies the positive strengthening effects of digital economy policies and environmental regulations on the relationship between new energy demonstration city construction and energy utilization efficiency. It clarifies the synergistic effects of policy tools and economic forms, providing a new perspective for understanding how multiple factors can jointly enhance the effects of new energy policies. Secondly, our research methods are innovative. Most existing studies analyze independent samples of individual cities, ignoring geographical interconnections. This study adopts spatial econometric analysis methods to empirically test and confirm the significant spatial spillover effects of the policy, providing a solid empirical basis for cross-administrative regional cooperation in energy and environmental governance.

2. Research Hypothesis

The theory of technological innovation states that economic development stems from “creative destruction”—the subversion of old technologies and systems by new technologies and business models [

13]. New energy demonstration cities can be seen as large-scale innovation testbeds and technology incubators, providing valuable application scenarios and testing platforms for a series of energy technologies that are still in the pre-commercialization stage. By concentrating resources on building public R&D platforms and implementing major demonstration projects, they not only reduce the technological innovation risks and costs of individual enterprises but also promote the rapid flow and iteration of knowledge and technology among the “government–industry–university–research–application” system. This systematic promotion transforms technological innovation related to energy efficiency improvement from isolated and occasional events into continuous and organized systematic activities, thereby significantly penetrating and reshaping the urban energy utilization model and fundamentally improving energy utilization efficiency. At the same time, the energy sector has typical negative externalities; for example, the environmental pollution and climate change costs caused by the consumption of traditional fossil energy are not included in the market pricing system, leading to excessive energy consumption and inefficient utilization. New energy technologies, due to their positive environmental externalities, raise the dilemma of high costs and low market acceptance (market failure) in the early stages of development. The new energy demonstration city policy is a major government intervention designed to correct this dual externality by building a policy-driven “social–technical testbed”. Furthermore, from the perspective of the agglomeration effect in spatial economics, the demonstration city policy guides the agglomeration of capital, talents, and technology in the new energy, energy conservation, and environmental protection industries [

14]. This geographical concentration not only generates economies of scale but also enables the development of specialized energy service companies through industrial linkages. These companies provide enterprises with professional energy efficiency diagnosis and improvement solutions through business models such as energy performance contracting (EPC), transforming energy efficiency improvement from a technical issue into a market-oriented service. This greatly promotes the introduction and popularization of advanced technologies and management models across industries, thereby improving energy utilization efficiency. In summary, as policy-driven socio-technical testbeds, new energy demonstration cities have systematically improved energy use efficiency by rectifying externalities, stimulating agglomeration effects, and accelerating technological iteration. Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Hypothesis 1. The construction of new energy demonstration cities can effectively enhance energy utilization efficiency.

From the perspective of information asymmetry and decision-making optimization, a core dilemma faced by traditional energy systems is information opacity and fragmented decision-making [

15]. Data on energy production, transmission, distribution, and consumption are scattered and lagging, leading to low accuracy in supply–demand matching and high redundancy in system operations. The big data, Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud computing technologies promoted in digital economy policies provide key tools for solving this dilemma. When these digital technologies are deeply integrated into the physical infrastructure of new energy demonstration cities, they can collect, transmit, and process massive real-time energy information flows [

16]. This makes the previous “black-box” energy system highly transparent and visible, significantly reducing information search and coordination costs in energy scheduling, trading, and management. Secondly, digital economy policies have led to the emergence of digital energy platforms. These platforms can break the former pattern of vertical monopoly and long chains in the energy industry, connecting tens of thousands of producers and consumers to form a new energy ecosystem with “source–grid–load–storage” interactions [

17]. Within the framework of demonstration cities, these platforms can easily incorporate decentralized distributed photovoltaics, user-side energy storage, electric vehicles, and other flexible resources and increase users’ willingness to participate in system regulation through market-oriented price signals. This platform-based ecological synergy achieves system synergy benefits far exceeding the simple sum of individual entities, expanding the breadth and depth of the resources that new energy demonstration cities can mobilize, thereby amplifying their potential to improve energy efficiency. In summary, digital economy policies have significantly reduced information and coordination costs by enabling transparency and platformization in the energy system while stimulating systemic synergy effects, thereby amplifying the potential for energy efficiency improvements in new energy demonstration cities. Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

Hypothesis 2. Digital economy policies can positively moderate the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency.

From the perspective of institutional complementarity, the effectiveness of any core policy depends on the coordination and support of other supporting systems [

18]. The new energy demonstration city policy mainly focuses on “establishing new systems”, i.e., cultivating and developing new energy industries and infrastructure, while environmental regulation policies focus on “abolishing old systems”, i.e., restricting and phasing out outdated technologies with a lower production capacity. The two are highly complementary in function. A lax environmental regulation attitude leads to an insufficient “abolition of old systems”: high-energy-consuming enterprises can still operate with low environmental costs, which weakens their demand for the new energy and energy efficiency technologies provided by demonstration cities and may even lead to “adverse selection” (the elimination of good enterprises by bad ones) [

19]. In contrast, a strict and effectively enforced environmental regulation system can form a “push–pull combination” policy package with the demonstration city policy: environmental regulations “push” enterprises away from high-carbon paths, while demonstration cities “pull” enterprises in by providing feasible low-carbon transformation solutions. This synergistic resonance between systems creates an optimal policy environment for improving energy utilization efficiency. Additionally, environmental regulations help establish strong societal values of resource conservation and environmental friendliness. They make energy utilization efficiency not just a corporate social responsibility or moral choice but a core factor in enterprises gaining competitive advantages in the market or even obtaining production permits. This fair, competitive environment shaped by regulations ensures that all enterprises can compete in terms of energy and environmental performance, allowing businesses in demonstration cities that take the lead in adopting high-efficiency and clean technologies to obtain real market returns [

20]. This reward mechanism will encourage more enterprises to take part, forming a virtuous cycle of “compliance–innovation–profit–re-innovation”, thereby greatly strengthening the positive spillover effect of the demonstration city policy. In summary, stringent environmental regulations and new energy demonstration city policies lead to an institutional synergy of “subverting old ways and establishing new ones”, creating a joint force combining push and pull that can effectively enhance the effect of energy efficiency improvements. Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

Hypothesis 3. Environmental regulations can positively moderate the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency.

The new energy demonstration city policy adjusts the price and demand signals for technological innovation by defining clear development goals for clean energy and investing policy resources. It increases the implicit costs of high-carbon technologies while reducing the relative prices of low-carbon and high-efficiency technologies [

21]. This non-market signal guides enterprises and scientific research institutions to concentrate R&D resources on new energy, energy conservation, energy management systems, and related fields such as materials science and information technology, directly driving the rapid growth of green technology patents. Meanwhile, as policy-designated units, demonstration cities promote exchanges and cooperation among various regional stakeholders by establishing public R&D platforms, organizing industry–university–research cooperation, and hosting industry technology forums. This reduces the transaction costs of technological innovation, accelerates knowledge accumulation and circulation, improves the innovation output efficiency of R&D investment, and drives cutting-edge, high-efficiency energy technologies from the laboratory to engineering demonstration, ultimately translating into observable improvements in energy use efficiency. In summary, the new energy demonstration city policy accelerates green technological innovation and transformation by guiding the agglomeration of R&D resources and promoting knowledge synergy, thereby driving improvements in energy use efficiency. Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 4 is proposed:

Hypothesis 4. The construction of new energy demonstration cities can effectively improve energy utilization efficiency through technological innovation.

From the perspective of industrial structural transformation, the policy shows a strong intention to foster industry. On the supply side, local governments vigorously encourage investment around the demonstration goals and prioritize the manufacture of new energy equipment and the development of new energy services and related information technology industries. As these emerging green industries expand in scale, their share in the regional total economic output continues to rise, driving significant improvements in regional energy economic efficiency [

22]. On the demand side, on the one hand, the vigorous development of the new energy industry generates strong intermediate demand for upstream producer services such as raw materials, high-end equipment manufacturing, and R&D design, driving the upgrading of related industries toward greener and more innovative approaches. On the other hand, the movement of the urban energy infrastructure toward greater cleanliness and intelligence leads to new requirements regarding energy inputs for all downstream industries. High-energy-consuming enterprises must undergo technological transformation to sustain operations in this environment; otherwise, they will face the risk of rising costs or market elimination. In addition, the policy has systematically reduced the barriers and costs that prevent enterprises from entering the green industry, increased the opportunity cost of adhering to traditional high-energy-consuming paths, and promoted the transfer of economic resources from high-energy-consuming sectors to low-energy-consuming ones. This has led to a decline in the energy consumption elasticity coefficient of the entire economic system, achieving a fundamental long-term improvement in energy use efficiency [

23]. In summary, the new energy demonstration city policy drives industrial optimization, fosters emerging industries on the supply side, and forms a pull and reverse-impact mechanism on the demand side, all of which promote long-term improvements in energy efficiency. Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 5 is proposed:

Hypothesis 5. The construction of new energy demonstration cities can effectively improve energy utilization efficiency through industrial optimization.

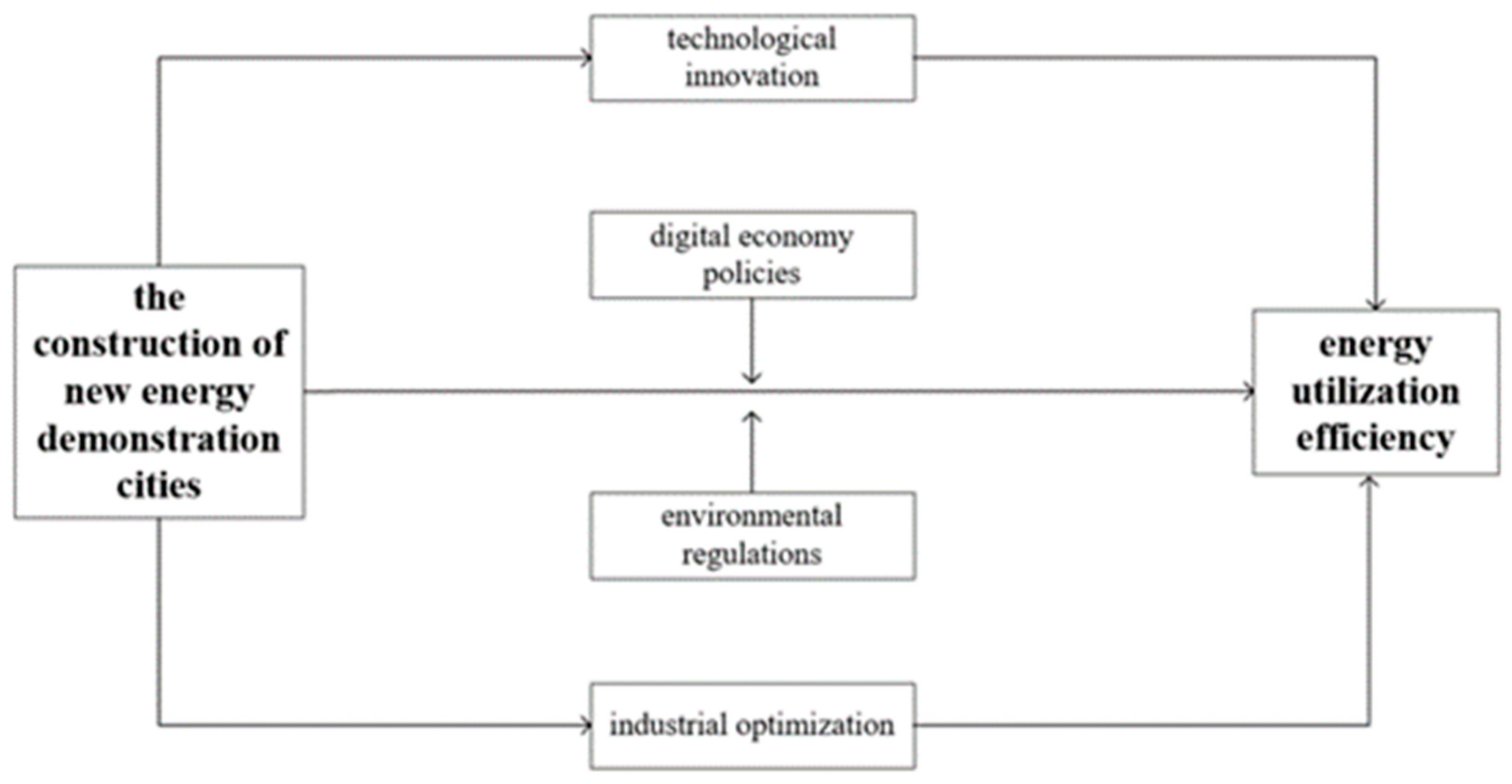

The hypothetical mechanism of the paper is shown in

Figure 1.

5. Further Analysis

Considering the regional disparities among Chinese cities, the construction of new energy demonstration cities may exhibit spatial correlation. Therefore, in this paper, we further analyze the spatial impact effects of new energy demonstration city construction on energy use efficiency.

5.1. Testing for the Existence of Spatial Effects

Firstly, the Moran’s I index is used to measure the spatial correlation in new energy demonstration city construction. The results are shown in

Table 11. It can be seen that during the period 2006~2023, the Moran’s I index for new energy demonstration city construction is significantly positive, indicating that during this stage, new energy demonstration city construction showed a significant spatial positive correlation trend of “high–high aggregation, low–low aggregation”.

5.2. Model Specification for Spatial Effects

Next, a spatial regression model is constructed to empirically test the spatial impact effects of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency. Firstly, model selection tests are conducted.

Table 12 shows the model test results. It can be seen that both the LR test and the Wald test significantly reject the null hypothesis that the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) can be simplified to the SAR model and the SEM model, indicating that the SDM has better adaptability.

Based on the model test results, a Spatial Durbin Model is constructed to empirically test the spatial impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency. The model is set as follows:

where

is the spatial weight matrix. In this paper, we select the geographical adjacency matrix for testing and use the geographical distance matrix for robustness testing;

is the spatial lag term for energy utilization efficiency, and

is the spatial lag term for new energy demonstration city construction.

and

represent regional fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively;

is the error term, and

is the intercept term. We focus on the coefficient

of

. If

is significant, this indicates that new energy demonstration city construction has a significant spatial impact effect on energy utilization efficiency.

5.3. Analysis of the Regression Results for Spatial Effects

Table 13 presents the test results for the spatial impact effects of new energy demonstration city construction on energy use efficiency. Column (1) shows the empirical results obtained using the spatial adjacency matrix, while column (2) presents those obtained using the spatial distance matrix.

From column (1), it can be observed that the correlation coefficient between Eue and Treat×Post is 0.024, statistically significant at the 1% level, once again confirming that the construction of new energy demonstration cities significantly promotes energy use efficiency. Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient between Eue and W×Treat×Post is 0.026, significant at the 5% level, indicating a significant positive spatial correlation between new energy demonstration city construction and energy use efficiency. That is to say, the construction of new energy demonstration cities in neighboring areas significantly enhances local energy use efficiency. This phenomenon may be attributed to the following mechanisms. Firstly, technological spillovers and learning effects occur between neighboring cities. The professional technical talents and management personnel cultivated during the construction of demonstration cities may move to work or provide consulting services in surrounding areas. Simultaneously, demonstration cities can drive the formation of new energy-related industrial chains in adjacent regions, and the planning and construction of large-scale new energy infrastructure often cover multiple areas. On the other hand, policy imitation and competition effects occur among neighboring cities. When a city observes that neighboring demonstration cities are gaining central financial subsidies, policy support, and economic growth through new energy development, it tends to imitate them and introduce similar supportive policies. Additionally, the success of nearby demonstration cities places pressure on local governments, prompting them to take measures to catch up and avoid falling behind in regional competition. As seen in column (2), after replacing the spatial weight matrix with the spatial distance matrix, the regression results remain consistent with those in column (1), demonstrating the robustness of the findings.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

Using data from 293 prefecture-level cities in China from 2006 to 2023 as the research sample, in this study, we empirically examined the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy utilization efficiency. The main research conclusions are as follows: First, the construction of new energy demonstration cities can effectively enhance energy use efficiency. Second, digital economy policies and environmental regulation positively moderate the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy use efficiency. Third, new energy demonstration city construction can effectively improve energy use efficiency through technological innovation and industrial optimization. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the promoting effect of new energy demonstration city construction on energy use efficiency is most pronounced in the eastern region, followed by the central region, while its impact on the western and northeastern regions is not significant. Additionally, the promoting effect is more evident in non-resource-based cities than in resource-based cities. Further analysis indicates a significant positive spatial correlation between new energy demonstration city construction and energy use efficiency, suggesting that the construction of such cities in neighboring areas significantly enhances local energy use efficiency.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on these research conclusions, the following policy implications are proposed: firstly, the demonstration policy should be further developed and promoted to leverage its leading and driving role. Based on the success of existing demonstration cities, more cities should be included in the project, selectively and in batches, and different access standards and support policies should be designed for the currently underserved western and northeastern regions. Secondly, policy coordination should be enhanced to achieve a “policy mix” effect and promote the integration of new energy into the digital economy. The government should take the lead in building urban energy data platforms, promoting data sharing, and incentivizing energy efficiency improvements and, at the same time, leverage the forcing and guiding role of environmental regulations, reasonably set and strictly enforce carbon emission and pollutant emission standards, and create stable market demand for new energy technologies. Thirdly, targeted support and guidance should be provided for key technological innovations and the strategic adjustment of industrial structures. Fiscal R&D investment should focus on breakthroughs and industrialization in core technologies, encourage “industry–university–research–application” cooperation, and accelerate the commercialization of technological achievement; simultaneously, fiscal, tax, and financial measures should be employed to guide traditional high-energy-consuming industries toward green and intelligent transformation. Finally, administrative barriers should be broken down and a new pattern of regional coordinated development created. Policies should reach beyond the scope of individual cities to plan and construct regional green coordinated development belts in a coordinated manner, with the establishment of experience exchange and compensation mechanisms between regions, allowing advanced regions to jointly build industrial parks in less developed regions and directly introducing advanced management models, technologies, and capital to maximize knowledge spillover effects.

Although this study provides useful empirical evidence to guide our understanding of the impact of new energy demonstration city construction on energy use efficiency, it still has certain limitations that highlight key future research directions. The sample in this study only extends up to 2023, meaning that the long-term dynamic effects of the new energy demonstration city policy may not yet be fully captured. At the same time, the research is primarily based on prefecture-level city data and does not explore the district, county, or enterprise levels, which may mask uneven development within cities. Future studies could employ data with longer time spans to assess the long-term effects and sustainability of the policy and utilize micro-level data from enterprises and households, or integrate new data sources, such as remote sensing and big data, to verify the micro-level effects and spatial heterogeneity of the policy at a more granular scale.