Operational Challenges and Potential Environmental Impacts of High-Speed Vessels in the Brazilian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

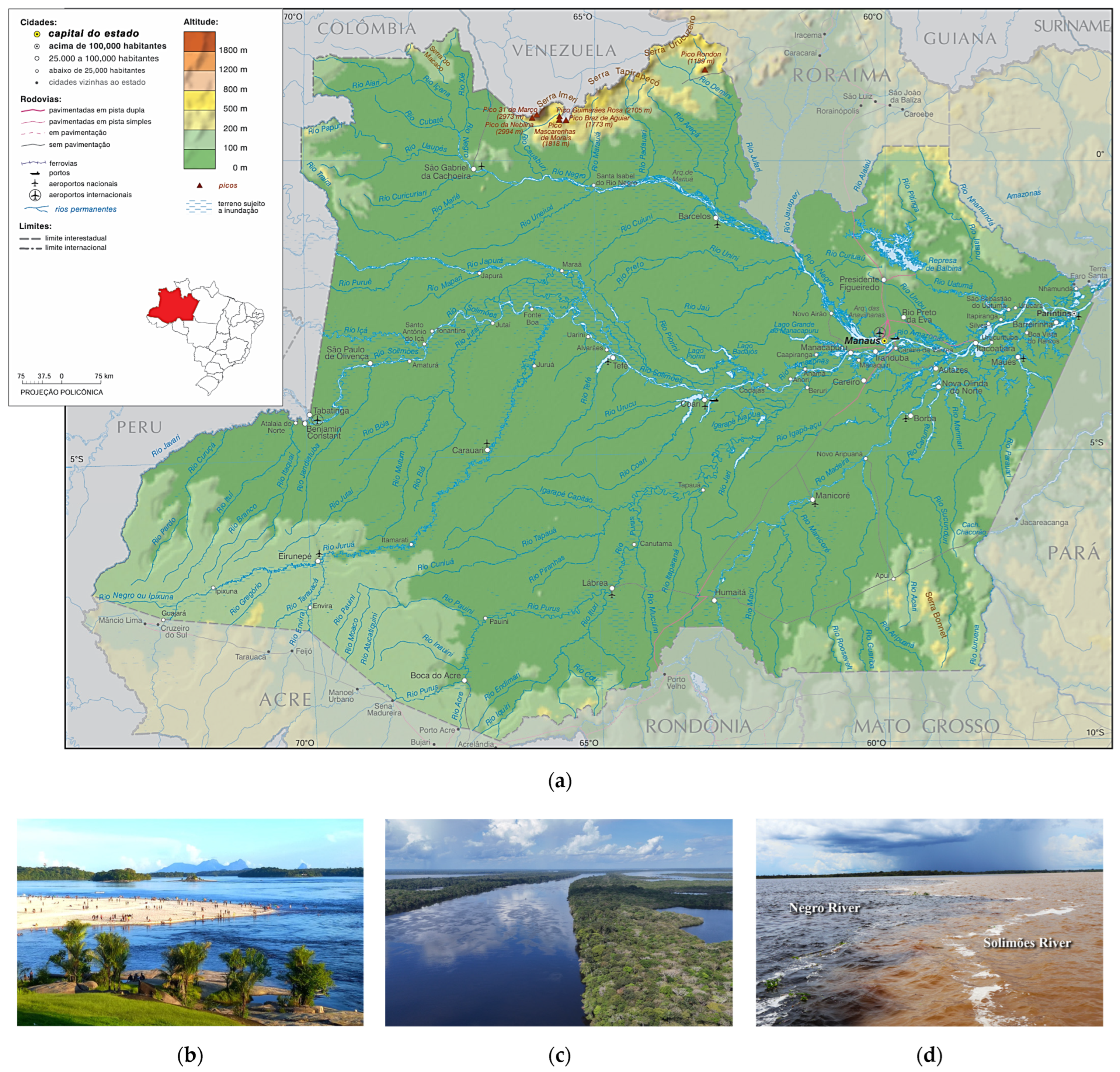

2.1. Region of Study

2.2. Procedure of Analysis

3. Operational Challenges

3.1. General Considerations for High-Speed Vessels

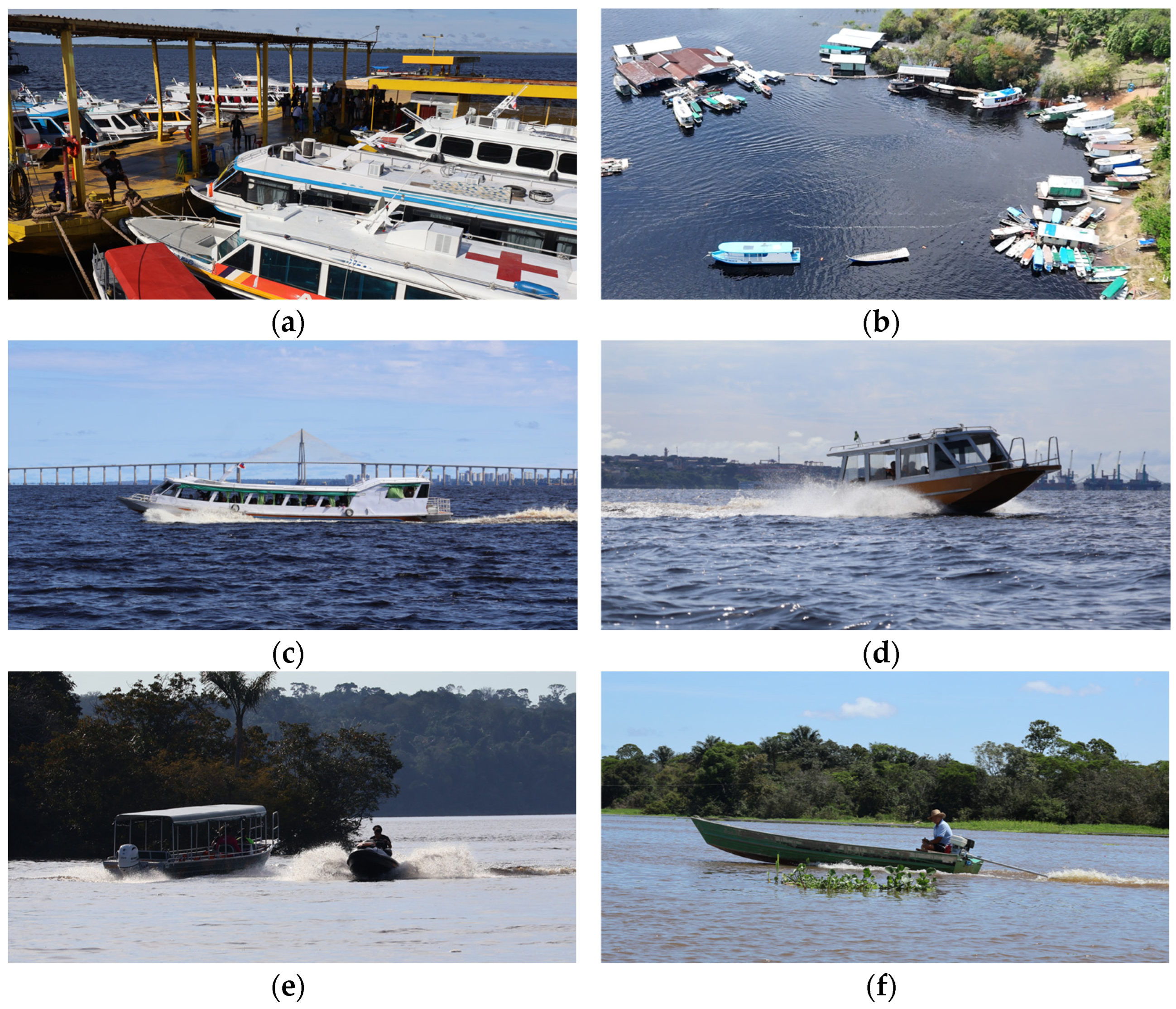

3.1.1. Types of Vessels

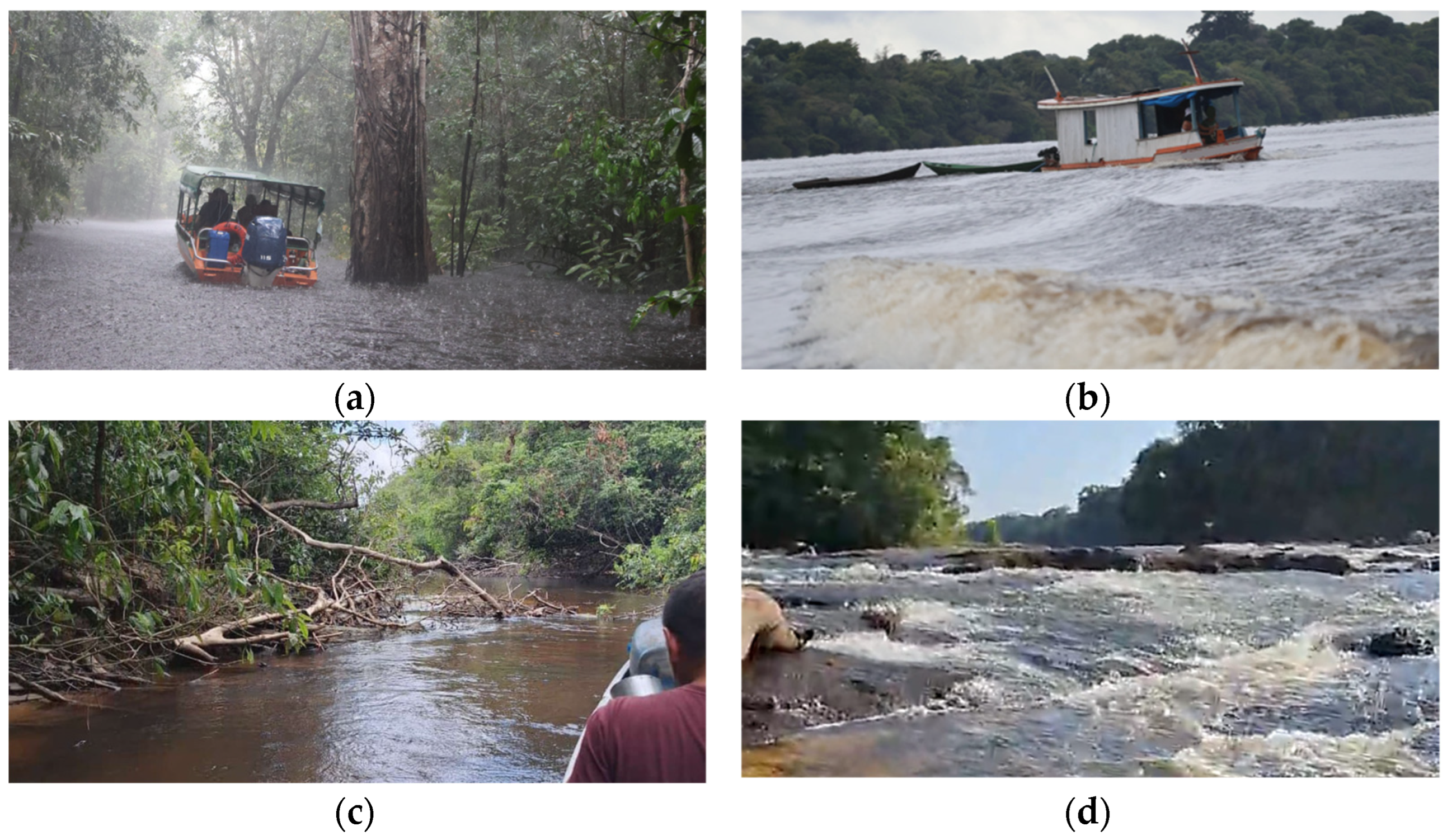

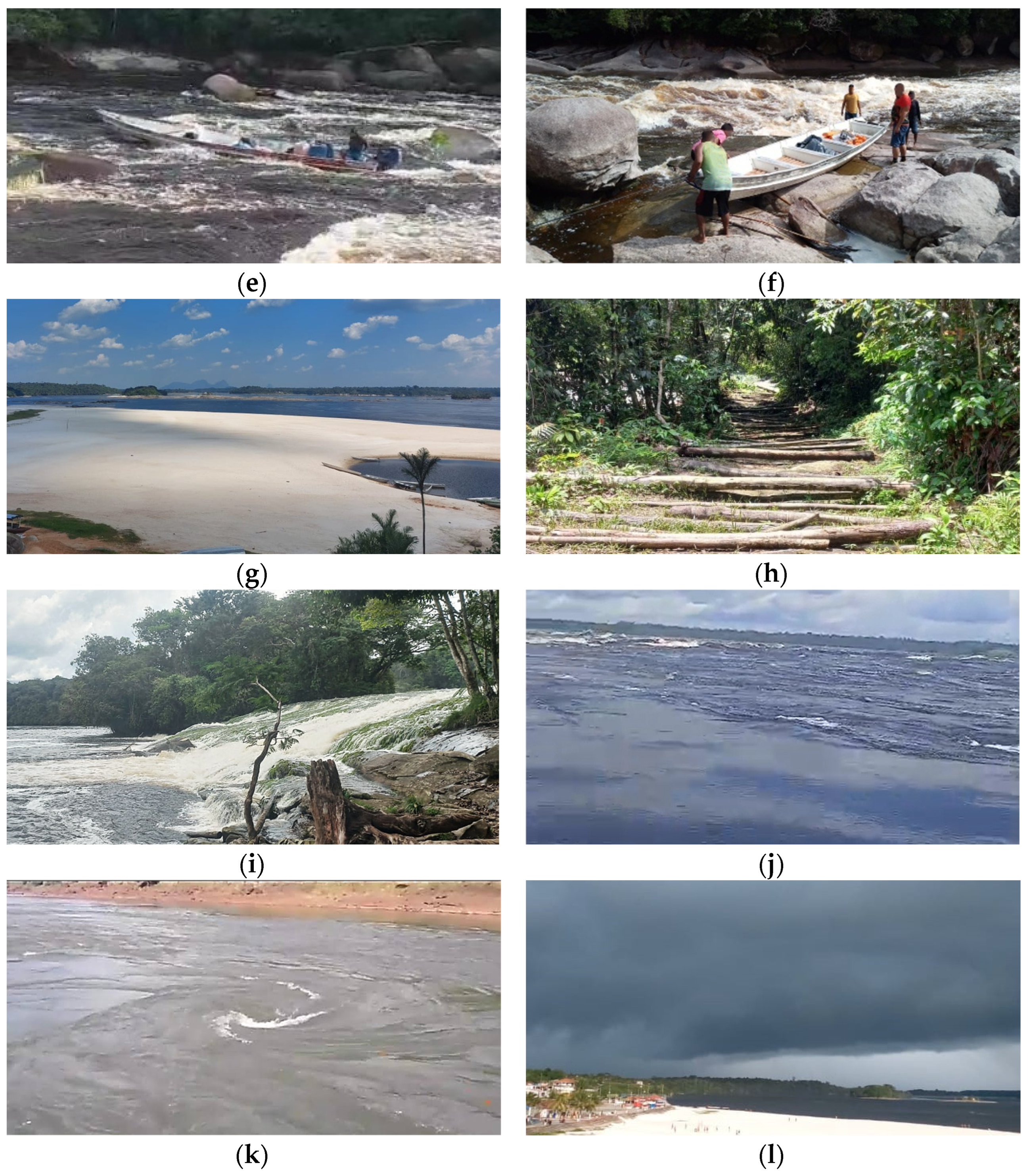

3.1.2. Seasonal Variations

3.2. Operational Challenges Identified in the Upper-Course River Region

3.3. Suggested Strategies to Overcome the Operational Challenges

3.3.1. Research and Innovation

- Application of knowledge in naval architecture and marine engineering: More advanced specific technical and scientific knowledge is required in analyzing every part of vessels’ project and operation, particularly with regard to structural integrity, materials, hydrodynamics, and propulsion. In the study region many vessels are built using age-old empirical techniques [26,27]. Digitalization and the three-dimensional design of hulls could allow for better analysis of stability, hydrodynamics, and structural optimization employing numerical simulation methods.

- Analysis of structural behavior: The structural analysis of the vessels used in the area would improve our understanding of their resistance during critical situations, such as collisions with rocks or sand banks. Investigating the stresses and deformations on hulls could be done, as proposed for ship grounding analysis by Zhou et al. [28]. Approaches based on Finite Element Methods (FEMs) to investigate structural behavior [29] are commonly applied elsewhere. Composite or plastic-based materials could be considered to make more flexible hulls. Moreover, composite patch techniques to repair damaged hulls, as proposed by Bianchi [30] for aluminum hulls and by Bianchi et al. [31] for underwater structures, could be considered, as they increase the useful life of vessels.

- Investigation of the hydrodynamics of vessels: High-speed vessels are used around the world for transportation, racing, and military purposes [32]. A more thorough analysis of the hull behavior of moving vessels improves their reliability in different conditions. Validated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods can be used to examine the hydrodynamic behavior of high-speed boats, exploring parameters such as drag and lift forces, and flow kinematics, both in steady-state or transient analyses [33]. Research into the dynamic behavior of the vessels in complex flow environments, such as those in Figure 3e, would require the use of time-domain simulations because of the transient flow conditions. In harsh environments, the effects of wind and waves on vessels could also be investigated. Again, CFD approaches can be used in investigating complex boat–flow interactions, either with mesh [34] or meshless [35,36] methods. Coupled FEM and CFD approaches [37] would allow for a more detailed fluid–structure interaction analysis. To improve the vessels’ dynamic stability, control systems such as interceptors or flaps [17] are often suggested. However, these could easily be damaged in the interaction of the vessels and obstacles.

- Investigation into the propulsion characteristics of the vessels: Navigating in rapids, see Figure 3d–f, using outboard motors, requires experienced operators who can avoid obstacles. In the study region, journeys can sometimes be undertaken in complex hydrodynamic conditions thanks to the operator’s knowledge of the region. However, there are always risks as conditions change throughout the year. Fixed and moving obstacles, such as tree trunks and rocks, are also an ever-present risk. It may be advisable to provide some degree of structural protection for the propellers using shock-resistant materials. Research could be encouraged on integrating shock-absorption technologies into motor-shaft-propeller systems to minimize the effects of impacts. Finally, the use of composites as potential replacements for propellers should be evaluated, as proposed by Islam et al. [38]. Although these authors described the pending tasks of this type of approach, they also presented potential benefits of marine composite propellers. Among them, it is possible to mention the high strength-to-weight ratio, damping, design flexibility, and susceptibility to low-velocity impacts with floating and submerged debris and aquatic animals.

- Applying national and international regulations to improve safety: Currently, marine activities in the Brazilian Amazon are mainly regulated by the Brazilian Navy through Maritime Authority Norms (NORMAM, [39]). However, it is possible that navigation with small high-speed crafts in remote regions presents particularities that need to be reviewed for implementation purposes. New recommendations related to the small vessels under study could be found in updates provided by International Maritime Organization (IMO) and in scientific literature on new technologies and mechanisms that would decrease damage to vessels operating in risk conditions [18,40].

- Possible new technologies: aerial or amphibious transport: In the future, perhaps marine vehicles will be designed to avoid obstacles, such as rocks and sand banks. A possibility for transportation in the dry season could be amphibious vessels that can operate in water and on land, as shown in Pan et al. [41]. Another possibility could be Wing-In-Ground (WIG) crafts, which operate in water and in the air, flying just above the water surface [42]. Yang et al. [43] gives examples of these devices, and the Aeroriver Barco Voador company has recently sought to implement this type of device as a means of transportation in the Brazilian Amazon [44].

- Research alternatives for signalization in remote regions: To improve signage and thus reduce accidents, devices powered by renewable energies, such as buoys [45], powered by solar, wind, and hydrokinetic energy, could be developed and installed in strategic positions to provide information, such as the direction of the main routes or warnings of dangers. These devices could also be equipped with sensors to measure and communicate environmental parameters to control stations (e.g., [46]); however, connectivity between the stations and the devices could be an additional challenge to be evaluated for remote regions.

3.3.2. Promote Education

- Disseminate technical knowledge: In remote regions of the Amazon, academic training in naval architecture and marine engineering is scarce. Although marine activities are common in the Brazilian Amazon, including frequent shipbuilding and repair activities [47], the only undergraduate courses in this region are in Manaus (at Amazonas State University) and Belem (at Federal University of Para). It is therefore suggested that lectures and courses are organized in Amazonian cities, including remote communities. Relevant technical advice could be presented to the owners and users of the small vessels regarding safety requirements, emergency procedures, and alternatives for safer navigation. Although this kind of information is available from the Maritime Authority in Brazilian Norms (e.g., NORMAM, [39]), perhaps there is a need to transmit such information in a more didactic way, through educational campaigns. Operational information should also be disseminated, such as recommendations for load distribution and stability on vessels, the proper use of propulsion systems, and emergency procedures.

- Disseminate information on safety to the local populations: The small vessels operating in the Brazilian Amazon should be equipped with basic safety kits, and users should know how to use the equipment properly. In the study region, it can be very difficult to supervise the use of safety equipment in remote regions, so users should constantly be kept up to date on safety procedures.

3.3.3. Improve Infrastructure

- Increase signage in dangerous locations: Due to the vast size of the study area, navigation signage is a complex issue; it cannot be installed in a short period. However, signage should be installed on the main navigation routes in especially dangerous and/or protected areas.

- Improving communication and maintenance services: It is suggested that communication and maintenance services for vessels be improved, including the implementation of boat repair services and emergency assistance, along the main routes connecting remote communities. Although financial resources would be needed for this, emergency assistance for navigation in complex water environments, such as in areas with rapids, could save lives and cause positive impacts to the transportation of essential goods.

- Alternative ways to get into the forest to complement the transport of boats: For the more remote communities, where some stretches of the river are not navigable and boats must be lifted out of the water and carried into the forest (Figure 3h), monitoring of these inaccessible routes would provide valuable data. Identifying where infrastructure could be improved, to reduce the energy and time required to access these communities, would greatly improve the well-being of their inhabitants.

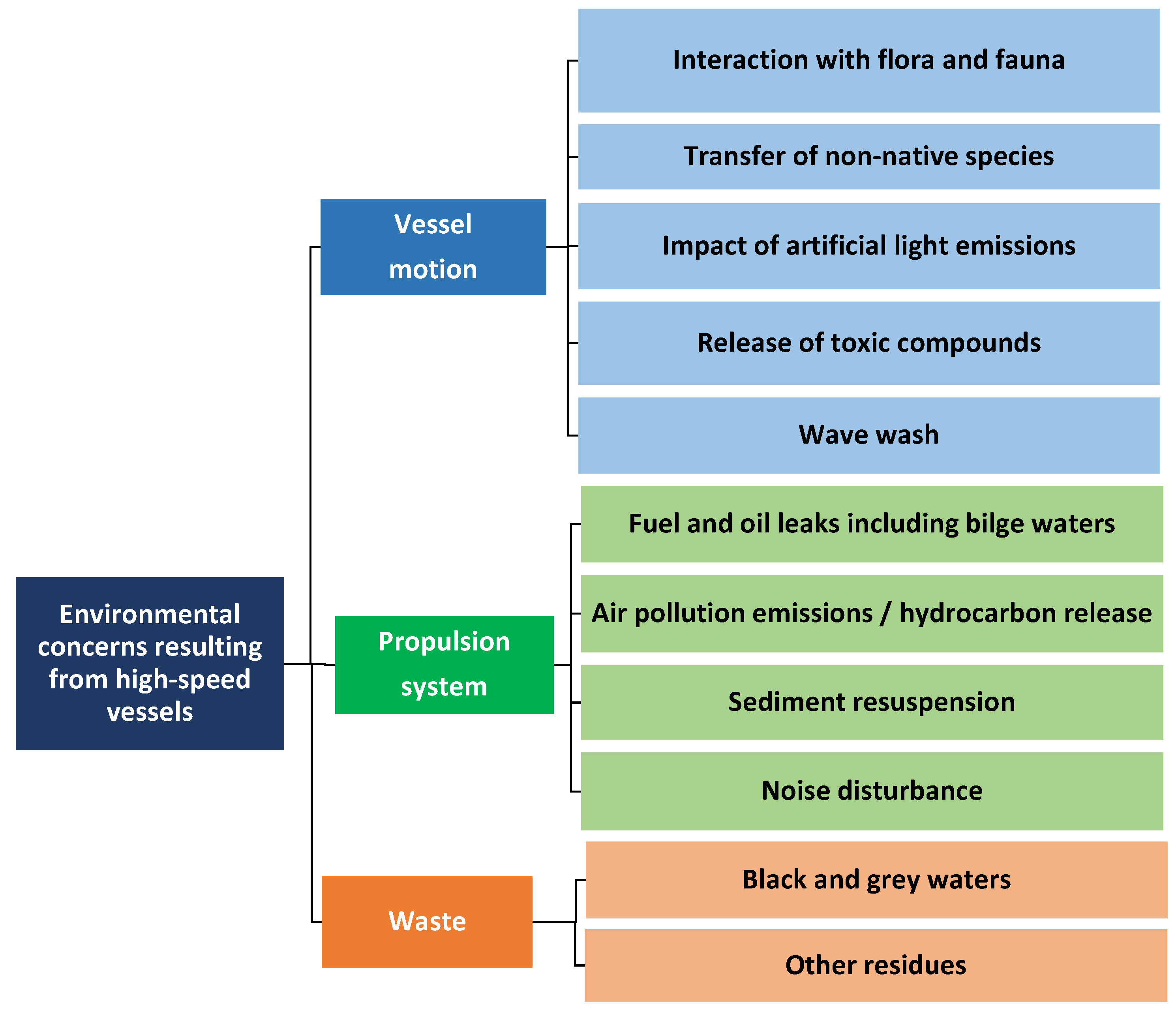

4. Potential Environmental Impacts

4.1. Impacts Related to Vessel Motion

4.1.1. Interaction with Flora and Fauna

4.1.2. Transfer of Non-Native Species

4.1.3. Impact of Artificial Light Emissions

4.1.4. Release of Toxic Compounds

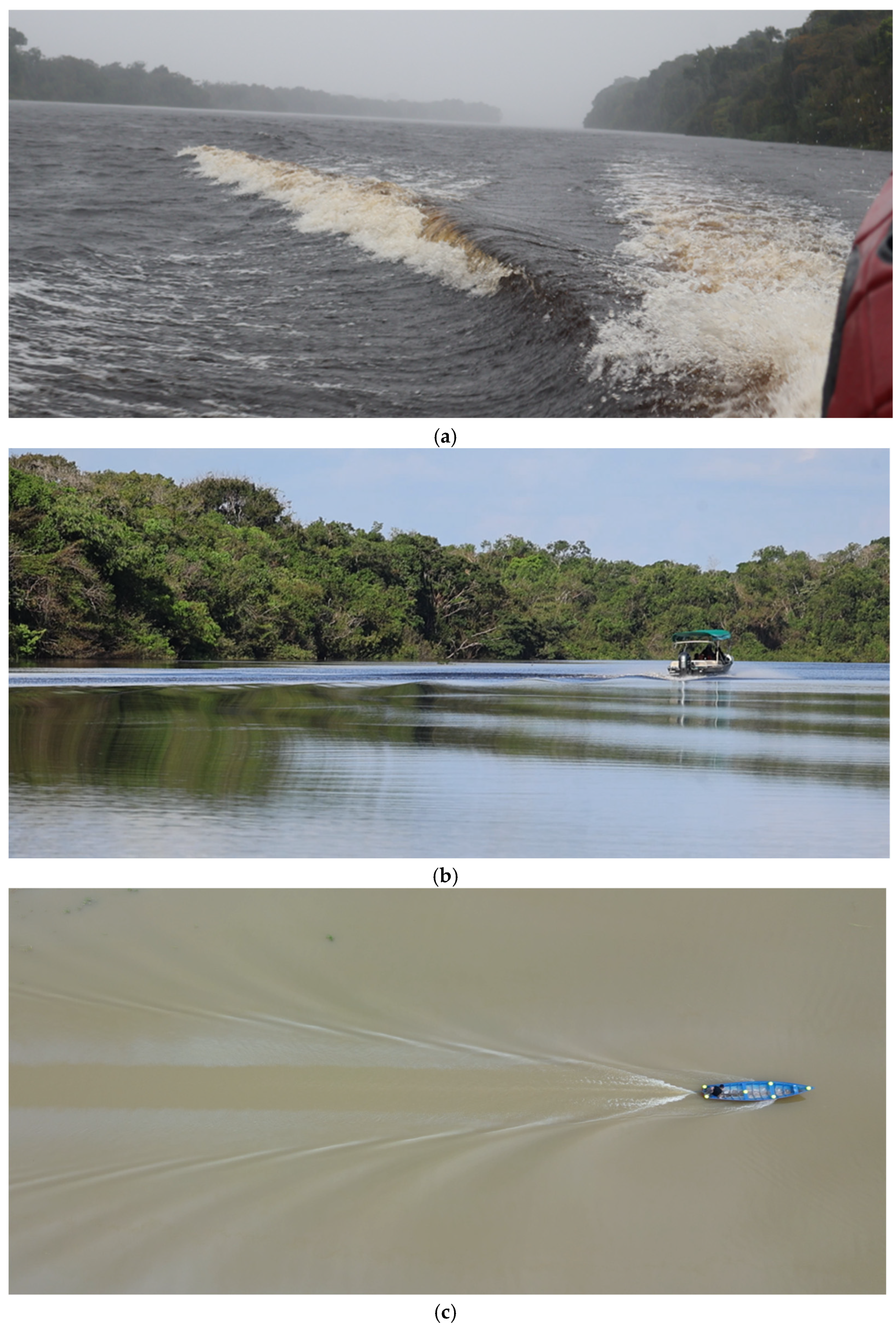

4.1.5. Wave Wash

4.2. Impacts Related to the Propulsion System

4.2.1. Fuel and Oil Leaks Including Bilge Waters

4.2.2. Air Pollution Emissions

4.2.3. Sediment Resuspension

4.2.4. Noise Disturbance

4.3. Impacts Related to Waste

4.3.1. Black and Grey Waters

4.3.2. Other Residues

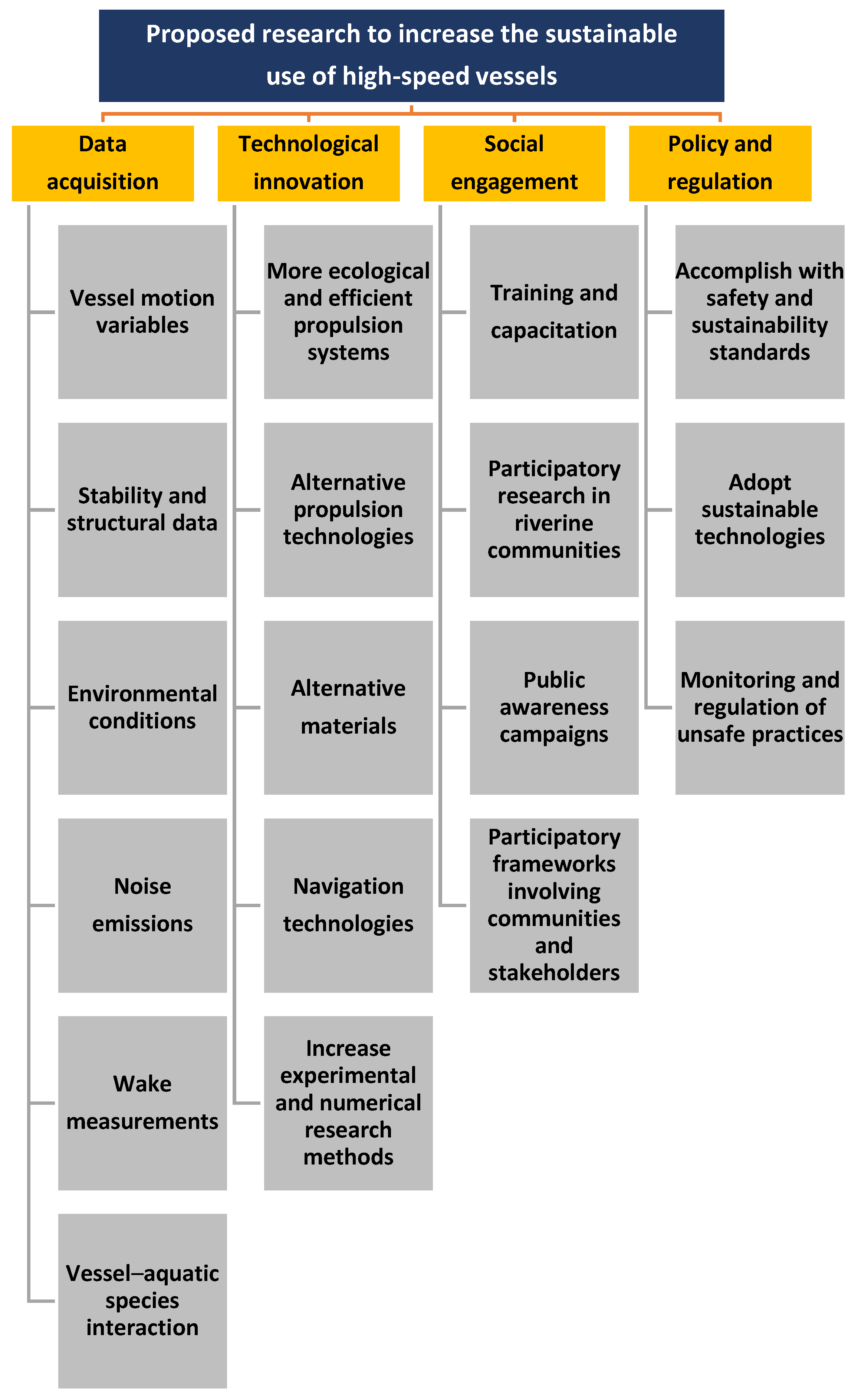

5. Further Research Developments

- Data acquisition: Firstly, information on vessel parameters and environmental conditions, acquired through measurement campaigns, is needed. In terms of operational challenges, it is necessary to gather more data on the motion of vessels in different operating conditions, which is relevant for research into control systems and propulsion [74,110]. Data on the stability of vessels is needed to determine safe loading conditions and evaluate potential dynamic instabilities [17]. Furthermore, data on the structural behavior of vessels is also required, particularly to quantify the typical damage on hulls resulting from collisions and groundings, and to develop alternative materials for repair and construction procedures [111]. Measurements of environmental conditions, such as wave height, currents, and wind speed, in regions frequented by high-speed vessels are crucial for analyzing possible real-life scenarios through numerical simulation, as done in sea-related applications [112]. Regarding environmental aspects, data on noise emissions, kinematics, and the energy of wake wash, and possible interactions with aquatic species, should be gathered, as suggested by Suprayogi et al. [85] for the wave wash phenomenon. To achieve this, research protocols may need to be developed to maintain ethical standards in research in protected environments.

- Technological innovation: The above information could be used in research and development in technological innovation. For example, more ecological and efficient propulsion systems could be developed, as suggested by [113,114]. This could be attained by optimizing vessel hull forms to minimize drag, wakes, and energy consumption, and by researching sustainable energy sources (e.g., biofuel, hydrogen fuel cells, etc.). The use of alternative materials, including composites, should be investigated for the construction and repair of lightweight, sustainable vessels. New technologies for safer and more efficient navigation, including smart technologies and monitoring sensors, should be tested [115]. Research into the relationship between analytical, numerical, and experimental approaches is crucial for the technological innovation of high-speed vessels, as demonstrated by [116].

- Social engagement: Research that promotes social action and seeks to engage the community and stakeholders should be encouraged [6,117]. Relevant topics include increasing the training of local builders and the pilots of high-speed vessels. Participatory research in communities could be carried out by engaging riverine communities to identify potential issues and co-develop solutions based on local needs and knowledge. Furthermore, public awareness campaigns and disseminating information through schools and the media are also advisable. The planning of participatory frameworks that involve local communities in decision-making and impact mitigation strategies are also important.

- Policy and regulation: Ensuring compliance with safety and sustainability objectives, in line with available policies and regulations, requires substantial work due to the particular operational challenges posed by high-speed vessels in some Amazon regions [5,7,11]. For example, research should be conducted into the speed limits of vessels, monitoring of loading procedures, optimized routing, scheduling, safety of operations, and so on. Moreover, policies and regulations applicable elsewhere should be collated to determine the feasibility of adopting green vessel technologies, facing decarbonization challenges, as discussed by [118]. Approaches to increase the monitoring and fiscalization of unsafe practices, including the operation of high-speed vessels in remote areas, are also needed. Proposals for integrated river traffic management mechanisms are also required, including the application of monitoring and control systems, to make vessel operations sustainable.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guayasamin, J.M.; Ribas, C.C.; Carnaval, A.C.; Carrillo, J.D.; Hoorn, C.; Lohmann, L.G.; Riff, D.; Ulloa Ulloa, C.; Albert, J.S. Evolution of Amazonian Biodiversity: A Review. Acta Amaz. 2024, 54, e54bc21360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F. The Amazon beyond the Forests, Rivers and Schools: Social Representations and Environmental Problems. Ambiente Soc. 2018, 21, e00250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fontes, J.V.; Maia, H.W.S.; Chávez, V.; Silva, R. Toward More Sustainable River Transportation in Remote Regions of the Amazon, Brazil. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoni-Andrade, A.C.; Fleischmann, A.S.; Papa, F.; de Paiva, R.C.D.; Wongchuig, S.; Melack, J.M.; Moreira, A.A.; Paris, A.; Ruhoff, A.; Barbosa, C.; et al. Amazon Hydrology from Space: Scientific Advances and Future Challenges. Rev. Geophys. 2021, 59, e2020RG000728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, J.V.H.; Hernández, I.D.; Mendoza, E.; Silva, R.; Santander, E.J.; Sanches, R.A. Challenges to Accident Prevention for High-Speed Vessels Used in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, J.V.; de Almeida, P.R.; Maia, H.W.; Hernández, I.D.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Silva, R.; Mendoza, E.; Esperança, P.T.; Sanches, R.A.; Mounsif, S. Marine Accidents in the Brazilian Amazon: The Problems and Challenges in the Initiatives for Their Prevention Focused on Passenger Ships. Sustainability 2023, 15, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, J.V.H.; de Almeida, P.R.R.; Hernández, I.D.; Maia, H.W.S.; Mendoza, E.; Silva, R.; Santander, E.J.O.; Marques, R.T.S.F.; Soares, N.L.; Sanches, R.A. Marine Accidents in the Brazilian Amazon: Potential Risks to the Aquatic Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredini, P.; Arasaki, E. Engenharia Portuária; Editora Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jézéquel, C.; Oberdorff, T.; Tedesco, P.A.; Schmitt, L. Geomorphological Diversity of Rivers in the Amazon Basin. Geomorphology 2022, 400, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO IMO and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/SustainableDevelopmentGoals.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Padovezi, C. Avaliação de Riscos Do Transporte Fluvial de Passageiros Na Região Amazônica. In Proceedings of the Congresso Nacional de Transporte Aquaviário, Construção Naval e Offshore-2012, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 15–19 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Padovezi, C.D. Segurança Operacional de Comboios Fluviais. In Proceedings of the 11° Seminário Internacional de Transporte e Desenvolvimento Hidroviário Interior, Brasília, Brazil, 22–24 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, H.W.; Said, M. Analysis for Resistance Reduction of an Amazon School Boat Through Hull Shape Modification Utilizing a CFD Tool. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2019, 53, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.D.A.; Brescovit, A.D.; Perbiche-Neves, G.; Venticinque, E.M. Spider (Arachnida-Araneae) Diversity in an Amazonian Altitudinal Gradient: Are the Patterns Congruent with Mid-Domain and Rapoport Effect Predictions? Biota Neotropica 2021, 21, e20211210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, S.F.; Souza, R.d.C.B.d.; Pinheiro, R. Territórios Da Gestão Socioambiental e Saúde Na Amazônia. Saúde Em Debate 2024, 48, e8734. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE Mapa Físico-Político de Amazonas—IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografía e Estatística). Available online: https://portaldemapas.ibge.gov.br/portal.php#mapa142 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Faltinsen, O.M. Hydrodynamics of High-Speed Marine Vehicles; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO HSC 2000 Code—International Code of Safety for High-Speed Craft, 2000—Resolution MSC.97(73). Available online: https://www.imorules.com/HSC2000.html (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Maia, H.W.; Fontes, J.V.; Bitencourtt, D.S.; Mendoza, E.; Silva, R.; Hernández, I.D.; Almeida, H.R. COVID Pandemics and Inland Transportation in the Brazilian Amazon: A Note on the Risks of Infection in Typical Passenger Vessels. COVID 2023, 3, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursino, M.W.d.J. Descrição de Embarcações Regionais Rápidas Comuns Em Parintins (AM) e Estudo Da Dinâmica de Uma Embarcação Tipo Expresso Usando Ansys Aqwa. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, I.T.; Omura, K.M.; Paixão, G.M.d. Análise Da Acessibilidade e a Percepção de Pessoas Com Deficiência Em Embarcações. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocupacional 2023, 31, e3383. [Google Scholar]

- de Neto, P.F.; Fontes, J.V.H.; Santander, E.J.O.; del Campo, E.R.B.; Cursino, M.W.d.J.; Sanches, R.A.; Feitoza, J.W.d.S.; Almeida, H.R. Rumo À Classificação de Embarcações Regionais de Alta Velocidade Comuns NA Amazônia Brasileira. Rev. Foco Interdiscip. Stud. J. 2024, 17, e5674. [Google Scholar]

- Zumak, A.; Fassoni-Andrade, A.C.; Pereira, H.C.; Papa, F.; dos Santos Silva, P.; do Nascimento, A.C.S.; Fleischmann, A.S. Riverine Communities in the Central Amazon Are Largely Subject to Erosion and Sedimentation Risk. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordon, N.G.; Nogueira, A.; Leal Filho, N.; Higuchi, N. Blowdown Disturbance Effect on the Density, Richness and Species Composition of the Seed Bank in Central Amazonia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 453, 117633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loredo-Souza, A.M.; Lima, E.G.; Vallis, M.B.; Rocha, M.M.; Wittwer, A.R.; Oliveira, M.G. Downburst Related Damages in Brazilian Buildings: Are They Avoidable? J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 185, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, N.V.M. Construção Naval No Amazonas; Editora Valer: Manaus, Brazil, 2022; ISBN 978-65-5585-049-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lins, N.V.M.; Rodrigues, L.R.Q.; Barreiros, N.R.; Machado, W.V. Construção Naval No Amazonas: Proposições Para o Mercado. In Proceedings of the Copinaval, Congreso Panamericano de Ingenieria Naval, Montevideo, Uruguay, 18–22 October 2009; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, C.B. Ship Grounding Simulation with Different Rock Shapes and Its Verification. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025, 20, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.L.; Cyrino, J.C.; Vaz, M.A. FPSO Collision Local Damage and Ultimate Longitudinal Bending Strength Analyses. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 17, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.W. Diver-Applied Underwater Composite Patch Repair on Aluminum Hulls. M.Sc. Dissertation, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Kwon, Y.; Alley, E. Composite Patch Repair for Underwater Aluminum Structures. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2019, 141, 064501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, R.; Shafaghat, R.; Shakeri, M. Hydrodynamic Analysis Techniques for High-Speed Planing Hulls. Appl. Ocean Res. 2013, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.; Zhang, M.; Kondratenko, A.A.; Hirdaris, S. A Review on the Hydrodynamics of Planing Hulls. Ocean Eng. 2024, 303, 117046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Tavakoli, S.; Dashtimanesh, A.; Sahoo, P.K.; Kõrgesaar, M. Performance Prediction of a Hard-Chine Planing Hull by Employing Different CFD Models. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, S.; Tagliafierro, B.; Mancini, S.; Martínez-Estévez, I.; Altomare, C.; Domínguez, J.M.; Viccione, G. Regular Wave Seakeeping Analysis of a Planing Hull by Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: A Comprehensive Validation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliafierro, B.; Mancini, S.; Ropero-Giralda, P.; Domínguez, J.M.; Crespo, A.J.; Viccione, G. Performance Assessment of a Planing Hull Using the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, B.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Deng, B. A Review of the Numerical Strategies for Solving Ship Hydroelasticity Based on CFD-FEM Technology. Ships Offshore Struct. 2024, 19, 1912–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Caldwell, R.; Phillips, A.W.; St John, N.A.; Prusty, B.G. A Review of Relevant Impact Behaviour for Improved Durability of Marine Composite Propellers. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 8, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinha Diretoria de Portos e Costas. Marinha Do Brasil. NORMAM—Normas da Autoridade Marítima. Available online: https://www.marinha.mil.br/dpc/normas-autoridade-maritima-brasileira (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Kartoğlu, C.; Kum, S. The Place of High Speed Crafts (HSCs) in Maritime Transportation. In Handbook of Research on the Applications of International Transportation and Logistics for World Trade; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 258–287. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Xu, X.; Liu, B.; Xu, H.; Wang, X. A Review on Drag Reduction Technology: Focusing on Amphibious Vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO Wing-in-Ground (WIG) Craft. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/safety/pages/wig.aspx (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, J.; Yao, G.; Liu, M. Survey on the Novel Hybrid Aquatic–Aerial Amphibious Aircraft: Aquatic Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (AquaUAV). Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2015, 74, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeroriver Aeroriver Barco Voador. Available online: https://www.aeroriver.com.br/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Pattanaik, B.; Rao, Y.N.; Murthy, P.K.; Viswanath, A.; Jalihal, P. Wave Powered Navigational Buoy Electrical Power Assessment during Open Sea Trial. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Power Electronics & IoT Applications in Renewable Energy and Its Control (PARC), Mathura, India, 28–29 February 2020; pp. 428–431. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, P.; Thoss, H.; Kaempf, L.; Güntner, A. A Buoy for Continuous Monitoring of Suspended Sediment Dynamics. Sensors 2013, 13, 13779–13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acritica Ministro de Portos e Aeroportos Entrega 15° Balsa Do Estaleiro Juruá. Available online: https://www.acritica.com/politica/ministro-de-portos-e-aeroportos-entrega-15-balsa-do-estaleiro-jurua-1.384898 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Carreño, A.; Lloret, J. Environmental Impacts of Increasing Leisure Boating Activity in Mediterranean Coastal Waters. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 209, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, A.; Becker, A. Impacts of Recreational Motorboats on Fishes: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 83, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigada, S.; Pesante, G.; Zanardelli, M.; Capoulade, F.; Gannier, A.; Weinrich, M.T. Mediterranean Fin Whales at Risk from Fatal Ship Strikes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, A.L. Fishes of the Amazon: Diversity and Beyond. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2019, 91, e20190260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.S.; Carvalho, T.P.; Petry, P.; Holder, M.A.; Maxime, E.L.; Espino, J.; Corahua, I.; Quispe, R.; Rengifo, B.; Ortega, H.; et al. Aquatic Biodiversity in the Amazon: Habitat Specialization and Geographic Isolation Promote Species Richness. Animals 2011, 1, 205–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagerman, J.; Hansen, J.P.; Wikström, S.A. Effects of Boat Traffic and Mooring Infrastructure on Aquatic Vegetation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ambio 2020, 49, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.-F.; Bernard, G.; Bonhomme, P.; Charbonnel, E.; Diviacco, G.; Meinesz, A.; Pergent, G.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Ruitton, S.; Tunesi, L. Protection and Conservation of Posidonia Oceanica Meadows; RAMOGE and RAC/SPA: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012; ISBN 2-905540-31-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sobreiro, T. Urban-Rural Livelihoods, Fishing Conflicts and Indigenous Movements in the Middle Rio Negro Region of the Brazilian Amazon. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 2015, 34, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.E.; Rivas, A.A.; Nascimento, F.A.; Siqueira-Souza, F.K.; Santos, I.L. The Effects of Sport Fishing Growth on Behavior of Commercial Fishermen in Balbina Reservoir, Amazon, Brazil. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008, 10, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.R.; Wells, R.S. Recreational Fishing Depredation and Associated Behaviors Involving Common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncatus) in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2011, 27, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clua, E.E. Managing Bite Risk for Divers in the Context of Shark Feeding Ecotourism: A Case Study from French Polynesia (Eastern Pacific). Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Issaris, Y.; Poursanidis, D.; Thessalou-Legaki, M. Vulnerability of Marine Habitats to the Invasive Green Alga Caulerpa Racemosa Var. Cylindracea within a Marine Protected Area. Mar. Environ. Res. 2010, 70, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metri, R.; Baptista-Metri, C.; Tavares, Y.A.G.; Lacerda, M.B.; Correia, E.L.; Soares, G.D.C.B.; Guilherme, P.D.B. Navigation Buoys as Stepping-Stones for Invasive Species. Ocean Coast. Res. 2024, 72, e24049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulman, A.; Ferrario, J.; Forcada, A.; Seebens, H.; Arvanitidis, C.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A.; Marchini, A. Alien Species Spreading via Biofouling on Recreational Vessels in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 2620–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.N.; Botter, R.C.; Folena, R.D.; Pereira, J.P.F.N.; Cunha, A.C. da Ballast Water: A Threat to the Amazon Basin. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 84, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, J.B.M.; da Costa, K.G.; de Oliveira, A.R.G.; Brito, E.P.; Nunes, Z.M.P.; Pereira, L.C.C.; da Costa, R.M. Ballast Water Transport of Alien Phytoplankton Species to the Brazilian Amazon Coast. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 360, 124656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longcore, T.; Rich, C. Ecological Light Pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.M.; Shillinger, G.L.; Robinson, N.J.; Tomillo, P.S.; Paladino, F.V. Effect of Light Intensity and Wavelength on the In-Water Orientation of Olive Ridley Turtle Hatchlings. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2018, 505, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüning, A.; Hölker, F.; Franke, S.; Preuer, T.; Kloas, W. Spotlight on Fish: Light Pollution Affects Circadian Rhythms of European Perch but Does Not Cause Stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, C.; Green, N.F.; McClure, E.C.; Osorio, D.C.; Vorobyev, M.; Marshall, N.J.; Cheney, K.L. Fish Use Colour to Learn Compound Visual Signals. Anim. Behav. 2017, 125, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Dann, P.; Chiaradia, A. Reducing Light-Induced Mortality of Seabirds: High Pressure Sodium Lights Decrease the Fatal Attraction of Shearwaters. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 39, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO Anti-Fouling Systems. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/anti-fouling.aspx (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Evans, S. TBT or Not TBT?: That Is the Question. Biofouling 1999, 14, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E.D. TBT: An Environmental Dilemma. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 1986, 28, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Í.B.; Iannacone, J.; Santos, S.; Fillmann, G. TBT Is Still a Matter of Concern in Peru. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ytreberg, E.; Bighiu, M.A.; Lundgren, L.; Eklund, B. XRF Measurements of Tin, Copper and Zinc in Antifouling Paints Coated on Leisure Boats. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molland, A.F.; Turnock, S.R.; Hudson, D.A. Ship Resistance and Propulsion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McConchie, J.A.; Toleman, I. Boat Wakes as a Cause of Riverbank Erosion: A Case Study from the Waikato River, New Zealand. J. Hydrol. N. Z. 2003, 42, 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zajicek, P.; Wolter, C. The Effects of Recreational and Commercial Navigation on Fish Assemblages in Large Rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.J. Displacement of Epifauna from Seagrass Blades by Boat Wake. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008, 354, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar-Kunze, E.; Dittrich, A.-L.; Gmeiner, P.; Liedermann, M.; Hein, T. The Effect of Ship-Induced Wave Trains on Periphytic Algal Communities in the Littoral Zone of a Large Regulated River (River Danube, Austria). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benassai, G.; Piscopo, V.; Scamardella, A. Field Study on Waves Produced by HSC for Coastal Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 82, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkegaard, J.; Kofoed-Hansen, H.; Elfrink, B. Wake Wash of High-Speed Craft in Coastal Areas. In Coastal Engineering 1998; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 1998; pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, N.L.D.N.; Fontes, J.V.H.; del Campo, E.R.B.; Santander, E.J.O.; Hernández, I.D.; Sanches, R.A. Estudo Das Ondas Geradas Por Uma Embarcação Regional Do Tipo Expresso Utilizando o Software Maxsurf Resistance. Rev. Foco 2023, 16, e3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, Z.-M.; Tao, L. Wash Waves Generated by Ship Moving across a Depth Change. Ocean Eng. 2023, 275, 114073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group 41, M.N.C.W.; Association, I.N. Guidelines for Managing Wake Wash from High-Speed Vessels: Report of Working Group 41 of the Maritime Navigation Commission; Pianc: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, G.K.; Abdullah, M.S.B.; Ashrafuzzaman, M. Wave Wash and Its Effects in Ship Design and Ship Operation: A Hydrodynamic Approach to Determine Maximum Permissible Speed in a Particular Shallow and Narrow Waterway. Procedia Eng. 2017, 194, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprayogi, D.T.; bin Yaakob, O.; Ahmed, Y.M.; Hashim, F.E.; Prayetno, E.; Elbatran, A.A.; Purqon, A. Speed Limit Determination of Fishing Boats in Confined Water Based on Ship Generated Waves. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 3165–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elentably, A.; van Essen, P.; Fahad, A.B.; Aljahdly, B.B.S. Innovative Floating Fuel Stations Enhance Seaport Productivity. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2024, 18, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Secades, L.A. Abatement of Bilge Dumping: Another Piece to Achieve Maritime Decarbonization. Soc. Impacts 2024, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.R.; Edman, M.; Gallego-Urrea, J.A.; Claremar, B.; Hassellöv, I.-M.; Omstedt, A.; Rutgersson, A. The Potential Future Contribution of Shipping to Acidification of the Baltic Sea. Ambio 2018, 47, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molski, B.; Dmuchowski, W. Effects of Acidification on Forests and Natural Vegetation, Wild Animals and Insects. In Studies in Environmental Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 30, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J.R.; Schreiber, R.K.; Novakova, E. Air Pollution Effects on Terrestrial and Aquatic Animals. In Air Pollution Effects on Biodiversity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 177–233. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, R.; Wittamore, K.; Mayer, H.; Roeder, D. Nautical Activities: What Impact on the Environment. Available online: https://www.europeanboatingindustry.eu/images/Documents/For_publications/Nautical-activities_what-impact-on-the-environment.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Ruiz, J.; Romero, J. Effects of Disturbances Caused by Coastal Constructions on Spatial Structure, Growth Dynamics and Photosynthesis of the Seagrass Posidonia Oceanica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.T.; Wigart, R.C. Effect of Motorized Watercraft on Summer Nearshore Turbidity at Lake Tahoe, California–Nevada. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2013, 29, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, M. The Effects of Suspensoids on Fish. Hydrobiologia 1985, 125, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Sriram, V.; Murali, K. Investigation of Ship-Induced Hydrodynamics and Sediment Resuspension in a Restricted Waterway. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 142, 103831. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Ouahsine, A.; Smaoui, H.; Sergent, P.; Jing, G. Impacts of Ship Movement on the Sediment Transport in Shipping Channel. J. Hydrodyn. 2014, 26, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, S.; Devillers, R.; Yurk, H.; MacGillivray, A.; McWhinnie, L.; Canessa, R. Noise Exposure from Commercial Shipping for the Southern Resident Killer Whale Population. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 136, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, M.A.; Simpson, S.D.; Radford, A.N. Noise Negatively Affects Foraging and Antipredator Behaviour in Shore Crabs. Anim. Behav. 2013, 86, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, W.D.; Insley, S.J.; Hilliard, R.C.; de Jong, T.; Pine, M.K. Potential Impacts of Shipping Noise on Marine Mammals in the Western Canadian Arctic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 123, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladich, F. Effects of Noise on Sound Detection and Acoustic Communication in Fishes. In Animal Communication and Noise; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johansson, L.; Andersson, M.H.; Majamäki, E.; Sigray, P. Underwater Noise Emissions from Ships during 2014–2020. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 119766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciulin, M.; Armelloni, E.; Falkner, R.; Rako-Gospić, N.; Radulović, M.; Pleslić, G.; Muslim, S.; Mihanović, H.; Gaggero, T. Characterization of the Underwater Noise Produced by Recreational and Small Fishing Boats (<14 m) in the Shallow-Water of the Cres-Lošinj Natura 2000 SCI. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 183, 114050. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, W.D.; Pine, M.K.; Citta, J.J.; Harwood, L.; Hauser, D.D.; Hilliard, R.C.; Lea, E.V.; Loseto, L.L.; Quakenbush, L.; Insley, S.J. Potential Exposure of Beluga and Bowhead Whales to Underwater Noise from Ship Traffic in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 204, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, P.D.; Serra-Sogas, N.; McWhinnie, L.; Pearce, K.; Le Baron, N.; O’Hagan, G.; Nesdoly, A.; Marques, T.; Canessa, R. Automated Identification System for Ships Data as a Proxy for Marine Vessel Related Stressors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 160987. [Google Scholar]

- Ytreberg, E.; Eriksson, M.; Maljutenko, I.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johansson, L.; Hassellöv, I.-M.; Granhag, L. Environmental Impacts of Grey Water Discharge from Ships in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP Drowing in Plastics: Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355467650_Drowning_in_Plastics_Marine_Litter_and_Plastic_Waste_Vital_Graphics (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Gündoğdu, S.; Bour, A.; Köşker, A.R.; Walther, B.A.; Napierska, D.; Mihai, F.-C.; Syberg, K.; Hansen, S.F.; Walker, T.R. Review of Microplastics and Chemical Risk Posed by Plastic Packaging on the Marine Environment to Inform the Global Plastics Treaty. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayassamy, P. Ocean Plastic Pollution: A Human and Biodiversity Loop. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvoisin, S., Jr.; Albuquerque, P.M.; Oliveira, R.L.; de Loiola, S.K.; Neta, A.S.; Estefani Batista, C.; Nobre Arcos, A.; dos Banhos, E.F. A Water Quality Index for the Black Water Rivers of the Amazon Region. Water 2025, 17, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P.; Suárez-Bermejo, J.C.; Sanz-Horcajo, E.; Pinilla-Cea, P. Reduction of Slamming Damage in the Hull of High-Speed Crafts Manufactured from Composite Materials Using Viscoelastic Layers. Ocean Eng. 2018, 159, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Hudson, D.; Temarel, P. The Influence of Forward Speed on Ship Motions in Abnormal Waves: Experimental Measurements and Numerical Predictions. J. Fluids Struct. 2013, 39, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo, J.; Dominguez-Jimenez, J.; Cabrera, J. Sustainable Boat Transportation throughout Electrification of Propulsion Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd Latin American Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS LATAM), Bogota, Colombia, 19–20 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stavroulakis, P.J. The evolution of ship propulsion technologies. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, A.; Vandchali, H.R.; Siddiqui, A.W.; Montewka, J. The Impact of Shipping 4.0 on Controlling Shipping Accidents: A Systematic Literature Review. Ocean Eng. 2021, 243, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Abdelwahab, H.; Soares, C.G. Experimental and CFD Investigation of the Effects of a High-Speed Passing Ship on a Moored Container Ship. Ocean Eng. 2021, 228, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.K. Riverine Passenger Vessel Disaster in Bangladesh: Options for Mitigation and Safety. Ph.D. Thesis, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, H.; Hansen, T. IMO off Course for Decarbonisation of Shipping? Three Challenges for Stricter Policy. Mar. Policy 2023, 147, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Filho, B.; Moutinho, P.; Nepstad, D.; Anderson, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Garcia, R.; Dietzsch, L.; Merry, F.; Bowman, M.; Hissa, L.; et al. Role of Brazilian Amazon Protected Areas in Climate Change Mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10821–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Operational Challenge | Issues |

|---|---|

| Navigation in shallow and/or rapid waters is dangerous | Lightweight hulls with flat bottoms are needed. The propellers tend to operate close to the water surface. Acceleration effects can cause displacement of cargo and passengers. Vessels must have good maneuverability and experienced pilots. Sudden motions can exceed recommended acceleration thresholds, affecting people’s safety. |

| Impacts with fixed or moving rocks are an ever-present threat | Hull damage (deformation, fractures). Shaft–propeller system damage. If the hull is perforated, the vessel would let in water. Capsizing. Injuries due to impacts, particularly at high speeds. |

| Interaction with small waterfalls is perilous | A loss of stability is increased if the hull comes out of the water. The bow may become submersed and then water could enter the boat. Sudden motions may propel people into the water. |

| Interaction of currents with underwater obstacles can cause waves or swirling flows | Dynamic instabilities are possible, particularly if the vessel is travelling at a high speed. Capsizing is a possibility if the formed flows are encountered at a high speed. The water may lie over rocks and resemble waves, which may confuse operators, and thus contribute to collisions. |

| Sand banks are often difficult to see | Grounding and collision damage to the hull or propulsion system. The vessel may need to be lifted off the sand bank and perhaps carried for a long distance. If the sand bank is extensive, it could cause water bodies to become isolated, and lead to subsequent difficulty in accessing fuel and essential services. |

| Severe environmental conditions make navigation more difficult | Perturbation of the river surface can cause waves that may affect small vessels. Strong winds could induce additional loads on the vessels, contributing to instability or capsizing. Heavy rain can flood open-hulled vessels. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fontes, J.V.H.; Hernández, I.D.; Silva, R.; Mendoza, E.; de Araújo, J.C.F.; Esperança, P.T.T.; da Silva, L.D. Operational Challenges and Potential Environmental Impacts of High-Speed Vessels in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310673

Fontes JVH, Hernández ID, Silva R, Mendoza E, de Araújo JCF, Esperança PTT, da Silva LD. Operational Challenges and Potential Environmental Impacts of High-Speed Vessels in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310673

Chicago/Turabian StyleFontes, Jassiel V. H., Irving D. Hernández, Rodolfo Silva, Edgar Mendoza, João Carlos Fontes de Araújo, Paulo T. T. Esperança, and Lucas Duarte da Silva. 2025. "Operational Challenges and Potential Environmental Impacts of High-Speed Vessels in the Brazilian Amazon" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310673

APA StyleFontes, J. V. H., Hernández, I. D., Silva, R., Mendoza, E., de Araújo, J. C. F., Esperança, P. T. T., & da Silva, L. D. (2025). Operational Challenges and Potential Environmental Impacts of High-Speed Vessels in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability, 17(23), 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310673