1. Introduction

Social justice forms the foundation of contemporary debates on access to public goods and increasingly influences the shaping of spatial structures. This is reflected in the philosophy of Henri Lefebvre [

1], who introduced the concept of the “right to the city” as an element of social justice in urban space, promoting the idea that residents should have an active role in shaping their surroundings. The classical concept of social justice, as outlined by John Rawls [

2] and further developed by scholars such as Nancy Fraser [

3], Edward Soja [

4], and David Harvey [

5,

6], emphasizes equality in access to common goods—including space. From this perspective emerges the concept of spatial justice, which examines how urban structures reinforce or suppress social diversity, participation, and inclusivity.

This issue is also significant from the perspective of the European Union’s sustainable development policy. For example, in the European Green Deal, spatial justice and inclusivity are identified as key criteria for transforming cities and revitalizing urbanized areas. The necessity of creating resilient, accessible, and climate-friendly urban spaces is emphasized [

7].

It should also be noted that the idea of the “right to the city” [

1] has taken on a new dimension in recent decades within revitalization efforts—including those involving university campuses, which serve as places of exchange of ideas, social interaction, and active co-creation of space. Research highlights that the “right to the city” refers not only to physical access but to genuine influence over the shaping of space—through participation, agency, and urban citizenship [

8]. From this perspective, a university campus can be viewed as a spatial community in which users have the right not only to be present but also to be heard—especially in the context of planning decisions.

The university campus, as a specific urban microscale, is becoming a space for testing and implementing not only technological solutions (e.g., Internet of Things systems) but also social ones—especially those related to inclusive planning and participatory design of shared spaces [

9,

10]. In this context, the campus is increasingly referred to as a Living Lab—a living environment where the academic community co-creates and tests innovative urban and social solutions [

11,

12,

13,

14]. These initiatives are developed in the spirit of spatial justice and universal design, in line with the principles of equality and accessibility [

15]. Within this framework, the role of the campus community is increasingly viewed not just as recipients but as co-creators of space. They are increasingly recognized as carriers of situated knowledge—practical, local, and rooted in everyday experience—which can support planning and design processes [

16,

17]. This approach opens up possibilities for democratizing planning practices and overcoming the traditional divide between experts and space users.

Tools such as geo-surveys, mobile applications, and serious (geo)games represent a key component of the so-called (geo)spatial participation. Their use enables the democratization of the planning process—from identifying needs to design and implementation. Moreover, by engaging different user groups in spatial deliberation, they support the principles of deliberative democracy and contribute to the development of the so-called Digital Agora [

18].

The upcoming 200th anniversary of the Warsaw University of Technology in 2026 provides both a symbolic and practical opportunity to initiate the transformation of the Central Campus. This raises important questions: How can the needs of campus users be defined, and how can the academic community’s participation in shaping the future campus be ensured?

This article aims to develop a methodology for applying spatial data mining methods to the exploratory analysis of data collected through extensive geosurvey research. The resulting spatial knowledge base may serve as a valuable decision-support tool for university authorities. The proposed methodology, tested within the Living Lab of one of Poland’s leading technical universities, can also be adapted for application at the scale of a city or a territorial administrative unit.

The article presents the results of a survey conducted among the academic community of the Warsaw University of Technology, representing the first stage in the creation of a university Living Lab on the WUT campus. The collected data made it possible to identify places important for identity, safety, or social integration—aspects that are often overlooked in traditional spatial analyses. The aim of the study was to demonstrate a methodology for using geospatial participation tools and spatial data mining methods in planning a just, inclusive, and sustainable university campus environment, taking into account the principles of spatial justice and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The methodology is based on the “Digital Agora” model, which integrates contemporary social geospatial participation technology with the Athenian concept of deliberative democracy, conceptualizing a hybrid digital and social platform.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, university campuses have increasingly been regarded as “Living Labs”—real-world test environments for innovative technological, social, and spatial solutions [

19]. The concept of a Living Lab is based on the idea of co-creating solutions through an iterative process involving end users, aligning with the need to design the campus of the future in a spirit of participation and adaptability.

Designing shared spaces at universities must now address not only environmental and functional challenges but also social ones. The concept of universal design involves creating spaces that are accessible to all users, regardless of age, ability, or social status [

15]. Applying this concept on university campuses represents a practical implementation of the idea of spatial justice.

University campuses around the world are undergoing increasingly spatial transformations, in which users—students, faculty staff, administrative staff, and local residents—actively participate [

20,

21]. Methods such as geo-surveys, participatory mapping (PPGIS), and even urban games—the so-called serious games—not only gather opinions but also foster engagement and a sense of agency among participants [

22,

23]. Revitalization can also serve a symbolic function of control, promoting uniformity rather than diversity, and order rather than openness [

24,

25]. This raises a crucial question: who is this space being designed for—and whose voices are being heard in the process. In many cases, marginalized groups such as service staff, persons with disabilities, or short-term campus users remain underrepresented in participatory processes. Their exclusion often results from digital barriers, limited access to consultation platforms, or institutional hierarchies that privilege academic and administrative stakeholders. As a result, the spatial outcomes may reinforce existing social asymmetries rather than challenge them.

Geoinformatics tools can now be effectively used for participatory spatial design, particularly geo-surveys—a method based on the concept of Volunteered Geographic Information [

26]. This approach enables users to actively identify spatial issues directly on a map. The methodology forms part of a broader framework known as “serious geogames”—geoinformation-based games that support spatial deliberation [

22,

23].

Research highlights the growing role of universities as spaces for implementing geospatial participation tools [

10,

12], where not only technological innovations (such as IoT and mobility systems) are tested but also mechanisms for co-decision-making and participatory planning. As such, the university campus can serve as a model example of an “urban laboratory,” developing scalable solutions that can be applied at the district, city, or regional level.

Table 1 presents the most relevant publications directly related to the research objectives. Several papers illustrate how Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) and related participatory geospatial methods can be effectively applied to revitalizing and planning university campuses. A study by Soares et al. [

10] on the Zernike Campus in Groningen integrates space syntax analysis with VGI collected through face-to-face interviews to capture users’ perceptions of space. Their findings highlight that VGI reveals socially valuable microspaces—such as those associated with safety, identity, or gathering—that are not always visible through formal spatial analysis, thus contributing to more inclusive and responsive campus planning. Similarly, Martella et al. [

12] developed a gamified framework called CampusMapper at the University of Münster, enabling students to map indoor spaces by drawing features such as doors and corridors based on floor plans. The gamification approach significantly increased user engagement and spatial data quality, demonstrating how VGI can support infrastructure management and emergency planning within university environments. Although focused on urban resilience, Moghadas et al. [

13] propose a scalable framework for integrating VGI into planning processes, emphasizing the importance of data credibility, consistency, and institutional oversight—principles directly applicable to long-term campus development strategies. Foundational literature on VGI and Public Participation Geographic Information System (PPGIS), such as that by Goodchild [

26] and others, further supports the role of participatory geographic data in democratizing spatial decision-making, especially in complex, multi-user environments, e.g., academic campuses. While direct case studies from Ivy League universities (e.g., Harvard Yard, Yale Campus Master Plan, Princeton, Columbia, UC Berkeley, or Cambridge University) are not readily available in the public domain, the methods and insights from these European examples provide a valuable foundation that can be adapted to the context of elite university campuses, enhancing the inclusivity, functionality, and long-term resilience of their spatial development.

In the context of campus design from the perspective of the academic community’s expectations, the literature describes mixed methods, including surveys, behavioral mapping, and spatial analysis. Comfort, safety, sustainability, and multifunctionality are the primary criteria for accepting campus design. Additional factors, such as greenery, soundscape, and thermal comfort, significantly influence the well-being of the academic community and the overall experience of being on campus. Spatial configuration and amenities significantly influence the evaluation of campuses [

27,

28].

Table 1.

Key studies on geoparticipation and campus revitalization in the context of spatial justice.

Table 1.

Key studies on geoparticipation and campus revitalization in the context of spatial justice.

| Paper | Research Topic | Tools/Methods | Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| Ducci et al. [29] | Geoparticipation in rural spatial planning | Maptionnaire (geo-questionnaire); participatory mapping | Demonstrates the usefulness of local perception mapping to inform landscape planning |

| Yang et al. [30] | Co-design and mobility planning in urban contexts | Agent-based modeling; serious games; public engagement workshops | Found serious games to be effective in engaging citizens in future planning |

| Butt and Li [9] | Web-based participatory Geographic Information System (GIS) for urban planning | Web GIS; online PPGIS platform | PPGIS facilitates early community involvement and spatial awareness |

| Harsia and Nummi [21] | Enhancing marginalized voices in planning | Participatory GIS; qualitative mapping | Highlights the importance of visual storytelling for inclusion |

| Delaney [23] | Game-based public engagement in city-making | Minecraft; co-design workshops; youth engagement | Digital games help include youth perspectives in spatial design |

| Szarek-Iwaniuk and Senetra [31] | Digital participation and social equity | Surveys; spatial Information and Communications Technology (ICT) access analysis | Reveals socio-spatial digital divides in public participation |

University campuses—particularly those historically situated within central urban structures—play a vital role in shaping the urban fabric. This occurs both from a historical perspective, where campuses are integral components of the existing city tissue, and in the context of contemporary urban development, as they continue to function as strong urban-forming agents [

32]. They serve as significant centers of social and economic relations on both local and global scales. The spatial configuration of a campus impacts the strengthening of socio-economic ties with the surrounding neighborhood and the wider city [

33,

34,

35].

The evolving role of the university in its core activities—research and education—necessitates spatial reconfigurations of academic campuses. In the field of research, such changes arise, among other factors, from the concept of the “entrepreneurial university” and the spatial strategies associated with it [

36]. In education, transformations stem from shifts in learning models, including peer-to-peer learning, new pedagogical approaches such as problem-based learning (PBL), an emphasis on teamwork, and the emergence of new user groups through lifelong learning—often with special needs [

37,

38].

An analysis of the primary conditions influencing campus development reveals several prevailing trends in campus design and revitalization. The International Sustainable Campus Development Network [

39] identifies four key areas that must be addressed when designing a sustainable campus: “Living Lab Approach (providing opportunities for students to engage with hands-on experience); Equality and Wellbeing for All (embracing the social aspects of sustainable development in creative and impactful ways); Sustainability on Campus (integrating sustainability into campus infrastructure and operations); Education as a Catalyst (learning activities as a catalyst for solutions-oriented approaches to global challenges)”. These thematic areas highlight four key categories of design determinants:

Integration with the City and Sense of Place: The mid-20th century model of detached, self-contained suburban campuses has been increasingly supplemented—or even replaced—by a renewed emphasis on integrating the university into the urban fabric [

40,

41]. In the case of historic campuses located within city structures, strategies such as urban renewal, adaptive reuse, and heritage conservation are applied, reflecting their cultural and historical value [

42]. Urban-integrated campuses also act as catalysts for local sustainable economic development [

43]. A strong sense of place enhances user identification with the university [

44], which in turn positively influences academic performance [

45].

Sustainable and Environmentally Oriented Design: Campus planning and revitalization increasingly follow principles of sustainable development and the circular economy [

46]. Environmentally conscious approaches promote the introduction of diverse greenery and rational water management systems. The implementation of green and blue infrastructure has a proven positive effect on user health [

47,

48,

49] and contributes to place identity [

50,

51]. Similarly, the introduction of walkability as part of sustainable mobility trends also supports user well-being [

52,

53].

Universal Design: Designing for all users, including those engaged in lifelong learning, as well as addressing emerging socio-economic relationships and the notion of the university as an inclusive institution, requires the application of Universal Design principles [

54]. These include solutions ensuring sensory-cognitive quality, ease of use, and social engagement for all [

55].

Creation of Informal Interaction Spaces: This aspect intersects with campus-city integration but also responds to new trends in higher education, which in the 21st century are moving away from the traditional teacher-oriented model [

56]. Instead, education increasingly centers on horizontal relationships among students and active engagement in the learning process [

57]. Informal, inclusive spaces for interaction foster a sense of participation and affiliation with the academic community, aligning with the symbolic dimension of university space [

58]. The symbolic and experiential qualities of campus environments significantly shape user experiences, empowering the creation of social ties [

59].

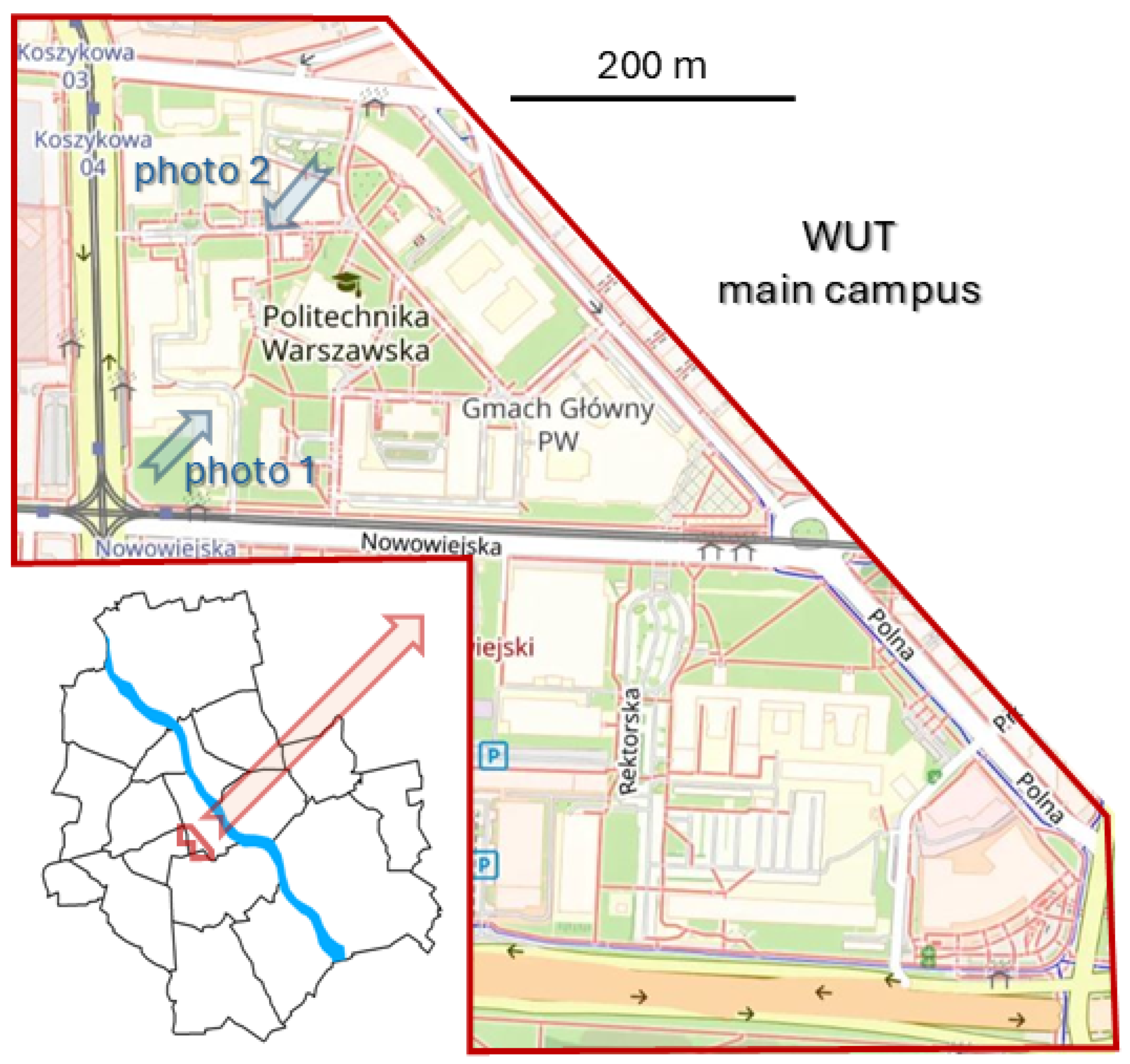

3. Diagnosis of Spatial Organization Challenges on the Central Campus of Warsaw University of Technology

Despite its central location and rich historical heritage, the Central Campus of Warsaw University of Technology (WUT) faces multidimensional spatial challenges (

Figure 1). Although it stands out for its architectural richness, the campus space is subordinated mainly to transport and communication functions—primarily car traffic.

WUT is one of the leading technical universities in Poland, boasting nearly two centuries of history and a strong scientific legacy. It conducts research in most key engineering disciplines, and its designation as a research university—granted as part of an elite group of ten institutions nationwide—further enhances its development potential. Nevertheless, a significant challenge remains: the low level of integration among the various faculties, which manifests not only organizationally but also spatially.

Even the university’s main campus, located in the very heart of the city, lacks cohesion. Its layout is dominated by automotive infrastructure, numerous parking lots, and roads that fragment the space, hindering pedestrian movement. There is a noticeable absence of an academic community atmosphere; the space does not encourage spontaneous interactions, intellectual exchange, or the sharing of ideas.

Despite its prestigious location and historical character, the campus faces a range of functional and spatial problems. One of the most pressing issues is its multilayered alienation: on the one hand, there is a lack of cohesion between university faculties and buildings; on the other, the campus has weak connections to the surrounding urban fabric. Physical accessibility is limited, and interaction with the local community is minimal. As a result, the campus functions as a largely closed enclave, with little openness to the city (

Figure 2a,b).

Additionally, the campus space is dominated by car traffic. An excess of parking spaces and vehicles encroaching on pedestrian zones hinders free mobility—especially for people with disabilities. The environment is characterized by hard surfaces and concrete, with a shortage of greenery, resting areas, and environmentally friendly solutions (

Figure 2b). Despite the presence of valuable elements, such as historic buildings from the late 19th century and protected natural monuments, large parts of the campus remain underinvested and underutilized.

Every day, approximately 15,000 students, 3000 employees, and several hundred guests are present on campus. The insufficient amount of green space (approx. 10% of the entire campus), lack of bike paths, and places to eat are significant problems for the entire academic community of WUT.

The planned revitalization of the campus aims to transform its character fundamentally—turning it into a modern, multifunctional, accessible, and sustainable academic space. Key objectives include improving accessibility, integrating green infrastructure in line with climate adaptation policies, and strengthening the sense of place by combining architectural heritage with a modern vision for the university’s development as a competitive research and teaching center.

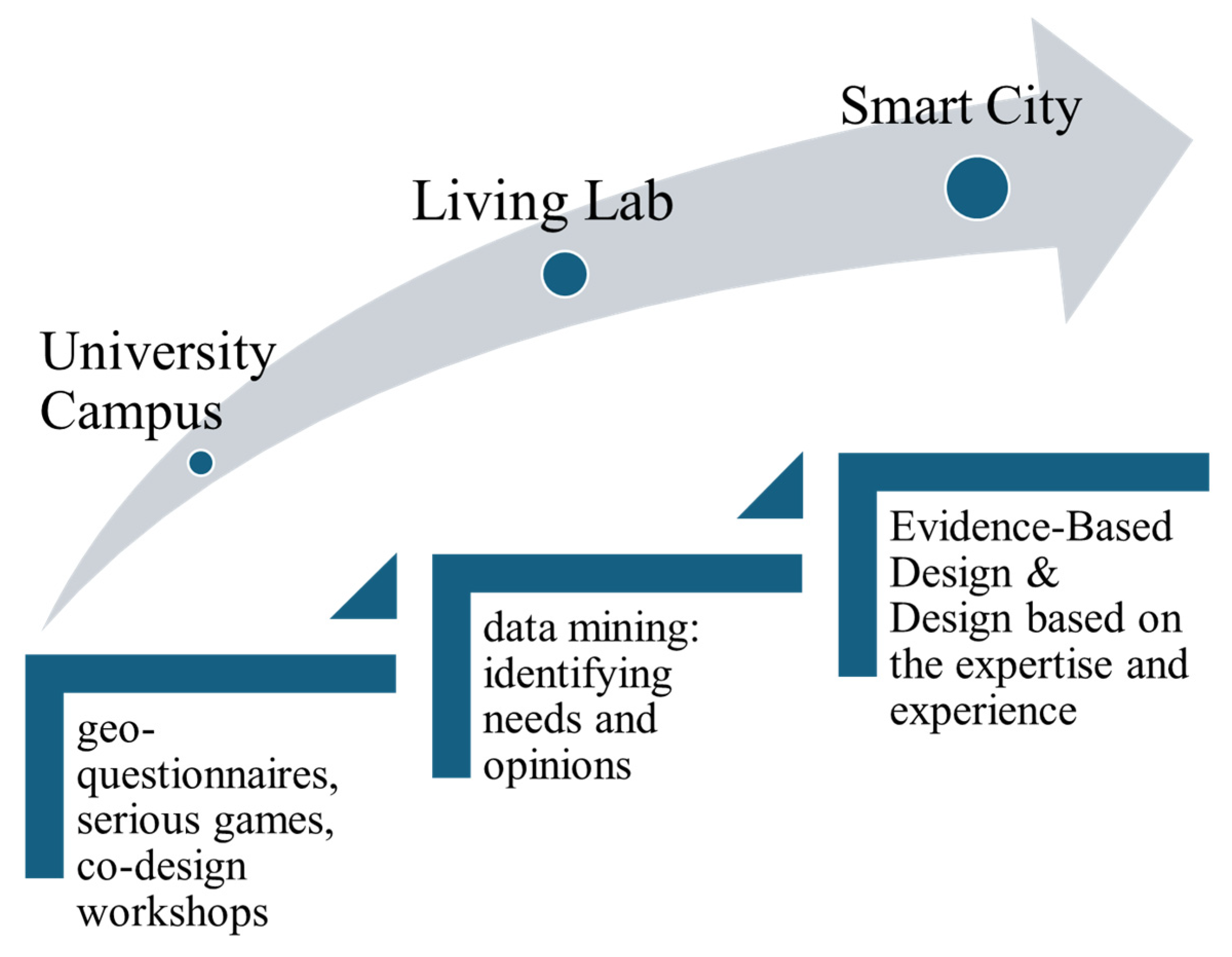

4. Research Methodology, Surveying the Academic Community’s Opinions Using a Geo-Questionnaire and Geospatial Data Analysis

All of the aforementioned trends converge in a holistic approach to campus design and revitalization, aiming to improve the quality of learning and research while affirming the contemporary mission of the university [

60]. Given the need to mitigate anthropogenic pressures, campus design increasingly employs adaptive reuse, focusing on the modernization of existing spatial structures. Such projects must respond to contemporary needs while respecting historical patterns of use. Three interrelated and complementary approaches are typically applied in campus design and revitalization:

Design based on the expertise and experience of the architect—incorporating the creative aspects of the design process, analysis of precedent cases, and so-called tacit knowledge [

61].

Evidence-Based Design (EBD)—relying on scientific studies concerning the impact of spatial environments on the functioning of academic communities and on data collected through observation of campus use, including data obtained from IoT technologies, enabling precise analysis of current spatial utilization [

62].

Participatory Design (PD)—involving academic communities in the design process [

63], including identifying needs and opinions via tools such as geo-questionnaires, surveys, serious games, and co-design workshops.

These approaches facilitate an understanding of how campus spaces should be shaped, how they currently function, and how they are perceived and desired by users. A balanced integration of all three approaches helps establish robust design rationales, thereby enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the design process and contributing to the overall improvement of campus space quality.

The revitalization of a university campus, taking into account the opinions of the academic community, is only the first step in the process of participatory planning for smart city development. The campus can be treated as a Living Lab of the city, while the developed methodology for activating the local community, as well as collecting and processing respondents’ opinions, can be applied in community-based city development, taking into account the idea of spatial justice.

The proposed methodology (

Figure 3) allows for not only the subjective treatment of the local community by taking into account the opinions of stakeholders but also the use of modern spatial data mining tools to analyze the collected data. The use of visually appealing geo-surveys or serious geogames, such as our invited Campus Changer, allows for the collection of “raw” spatial data, while their processing is carried out by specialists using advanced methods of exploratory spatial data analysis. Methods tested and refined at the scale of a university campus can then be implemented at the scale of metropolises aspiring to become smart cities. This approach is a realization of the Digital Agora concept [

18]. The essence of VGI lies not only in obtaining spatial data from residents (the classic “citizens as sensors” approach [

26], but also in stimulating them to be active in terms of social (geo)participation and the creation of an open (geo)information society are concerned. The contemporary challenge of the “smart city” era is the creation of a Digital Agora, which not only facilitates (and analytically supports) social debate on spatial planning but also creates tools for analyzing spatially localized social data.

The proposed methodology (

Figure 3) involves collecting input from the local community through simple and user-friendly geo-surveys accessible to non-experts, followed by the use of advanced spatial data mining tools to analyze the “raw” data. This process leads to the development of a spatial knowledge base and decision-support tools intended for use by professional planners. This approach, understood as Participatory Evidence-Based Design, can first be tested at the spatial scale of a university campus Living Lab, and subsequently adapted for implementation at the city level—particularly in urban areas aspiring to become smart cities.

Following the proposed methodology (

Figure 3), the authors developed two geoinformation tools—the serious geogame Campus Changer and a geo-questionnaire of the same name. The results of the geogame are discussed in a separate article [

64]. This article focuses on the analysis of data collected via the geo-questionnaire.

In March 2025, an email explaining the purpose of the study was sent to approximately 30,000 members of the WUT academic community—including staff, PhD candidates, and students. The questionnaire was also made available to campus guests and permanent residents of the central campus. The geo-questionnaire was developed using ArcGIS Experience Builder (Developer Edition) and ArcGIS Survey123 Connect. The use of ArcGIS Survey123 Connect allowed for customization of both the style and content of the questions. The application stored collected data in an ArcGIS Online repository, which facilitated subsequent data processing and analysis in the ArcGIS Pro environment. ArcGIS Survey123 Connect also made it possible to embed an interactive map within the questionnaire, allowing users to select specific locations—i.e., to mark areas on the WUT Central Campus that, in their opinion, should undergo specific changes. Due to its capacity to create modern and visually appealing applications, ESRI’s ArcGIS Experience Builder (Developer Edition) was also employed in the app’s development. Experience Builder enabled the integration of the questionnaire with logos and background information about the study’s purpose, and made it possible to prepare a mobile-friendly version of the geo-questionnaire. Since Experience Builder does not natively offer a widget or function to collect and display all the drawn areas from the questionnaire on a map, a custom function was developed to meet the requirements of the geo-questionnaire fully. The application was ultimately deployed within the CENAGIS domain of the IT infrastructure of Warsaw University of Technology.

The study fully utilized the integration of descriptive questions with an interactive map, allowing respondents to indicate locations in need of change and specify the types of interventions required (e.g., more greenery, improved cycling infrastructure, enhanced safety, reduced car traffic).

The general section of the questionnaire included questions assessing the campus—its appearance, functionality, and atmosphere—as well as preferences for changes and the perceived need for transformation. The questionnaire also included a demographic section that identified the type of user (student, staff member, or guest) and the frequency of their use of WUT campus spaces.

The geo-questionnaire remained active for one month, yielding 710 complete responses and nearly 1000 identified problem locations. These were analyzed using GIS tools and spatial statistics.

5. Results

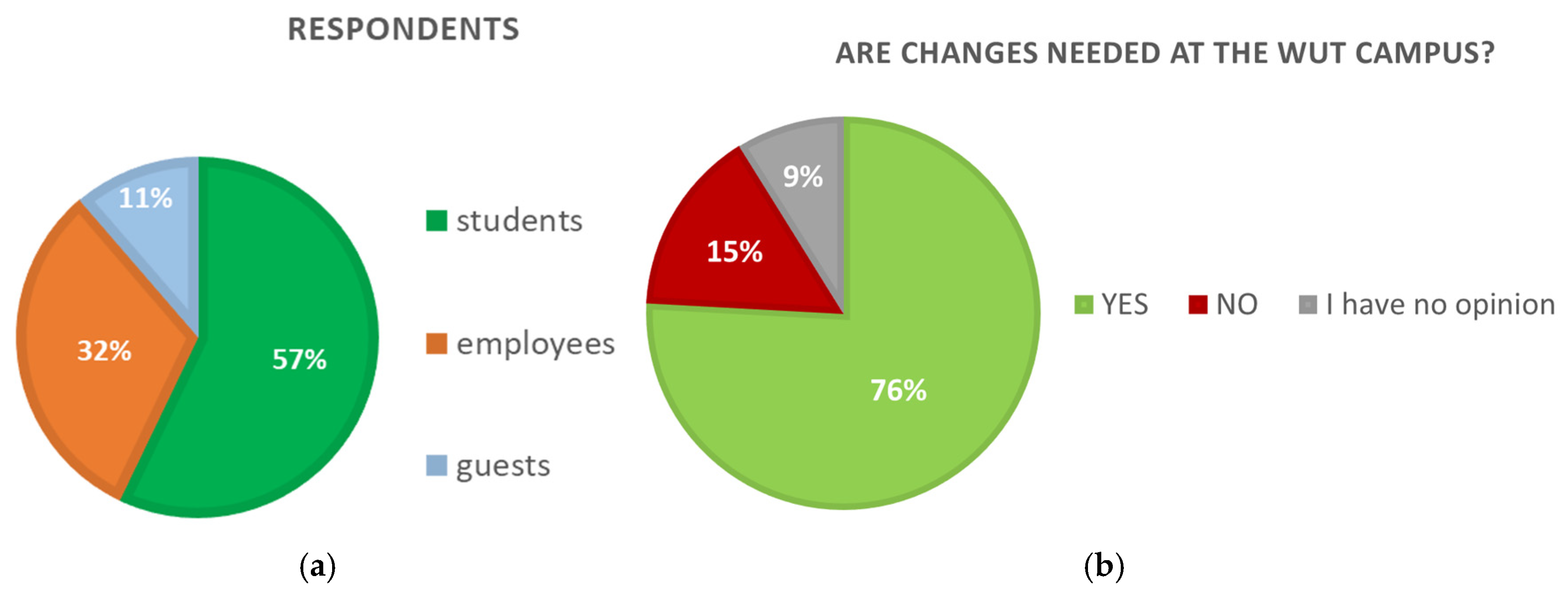

The survey, completed by 710 participants (405 students, 227 university staff, and 78 guests)—a sufficiently large and representative sample of the WUT academic community—reveals a complex picture of user experiences on the Warsaw University of Technology campus. The largest group of respondents was students (57%), followed by university staff (32%), and guests, residents, and alumni (11%) (

Figure 4a). Three-quarters of respondents stated that the campus requires changes (

Figure 4b). Only 15% expressed the opposite view, while 9% were undecided. This strong preference for transformation suggests that the campus is not perceived merely as a neutral “backdrop” for educational and professional activities—instead, it becomes an active component of daily experiences and emotional evaluations. The campus space is continually negotiated—both functionally (Can I work here? Rest? Eat?) and symbolically (Do I feel welcome here? Does this space exclude me, or does it represent me?).

These results can be interpreted as a sign of growing awareness among campus users that institutional space is not “set in stone,” but instead can—and should—respond to the evolving needs, lifestyles, and expectations of the academic community.

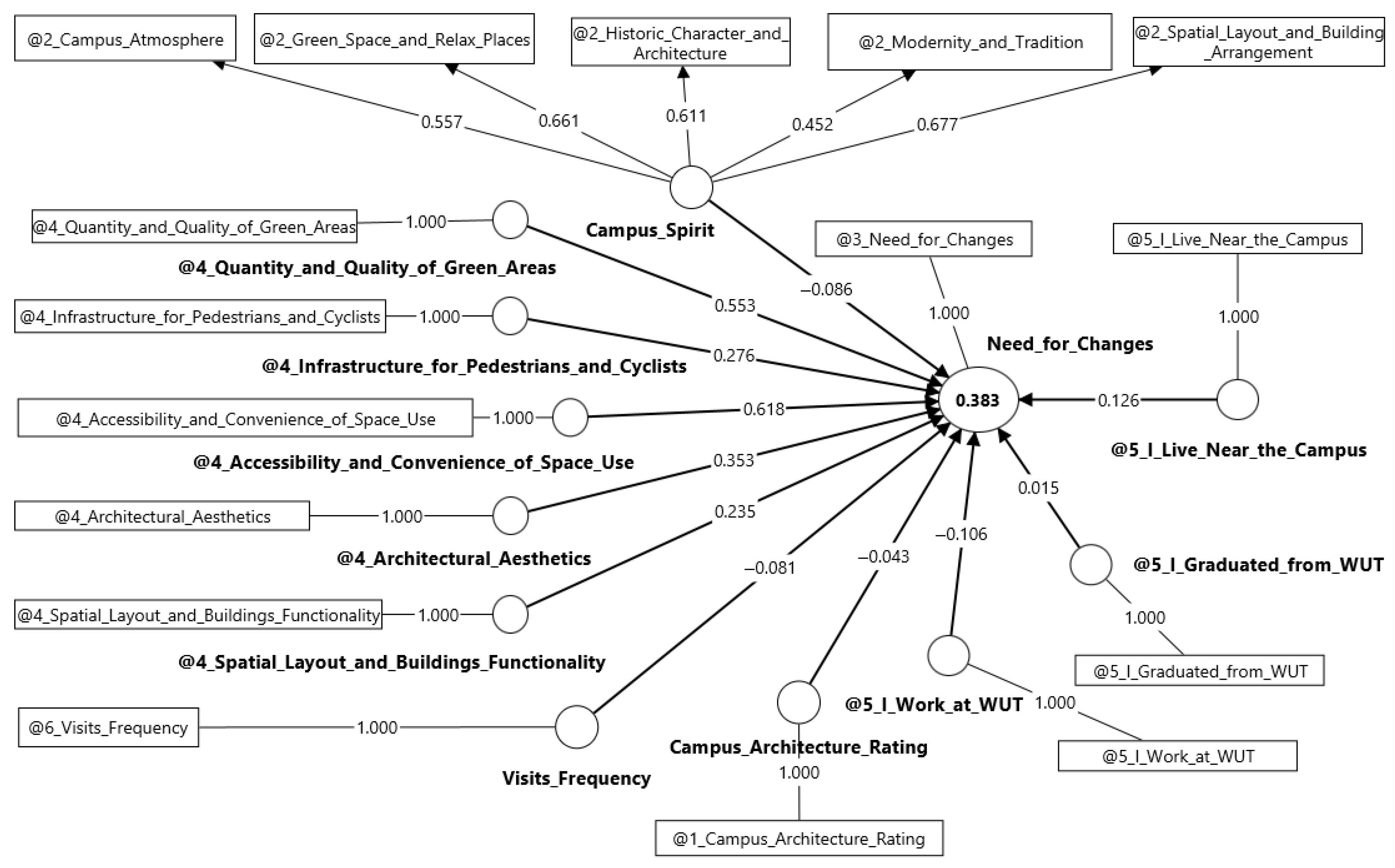

The robust inclination toward campus transformation revealed in the survey results calls for a deeper analysis to identify the factors driving this demand for change. To develop a comprehensive regression model, the authors employed the structural equation modeling (SEM) method. Research using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method has been frequently employed to assess satisfaction with campus urban design [

65,

66]. A statistical analysis of community expectations was conducted using the results of a survey carried out as part of this project. A structural model was prepared to assess the reasons for the need for changes at the WUT campus.

The outcome variable in the PLS-SEM model prepared in SmartPLS 4 software was the Need for Change construct. The exogenous variables in the model were single-item constructs measured by survey questions, and the construct Campus_Spirit, which was measured reflectively by indicator variables: Campus Atmosphere, Green Space and Relax Places, Historic Character and Architecture, Spatial Layout, and Building Arrangement. Single-item constructs were Quantity and Quality of Green Areas, Infrastructure for Pedestrians and Cyclists, Accessibility and Convenience of Space Use, Architectural Aesthetics, Spatial Layout and Buildings Functionality, Visits Frequency, Campus Architecture Rating, Working at the Warsaw University of Technology, the Fact of Graduating from the University, and Living Near the Campus. The PLS-SEM model is presented in

Figure 4. Latent variables’ fit accuracy and model accuracy were checked in accordance with [

67]. The model explains 38.3% of the variance.

Among the variables presented in

Figure 4 in the model paths directly explaining the dependent variable Need for Change, only Visits Frequency and variables related to campus infrastructure: Quantity and Quality of Green Areas, Infrastructure for Pedestrians and Cyclists, Accessibility and Convenience of Space Use, Architectural Aesthetics, Spatial Layout, and Buildings Functionality are statistically significant. The variable Visits Frequency has a negligible regression coefficient and therefore has little impact on the dependent variable. The regression coefficient on the Campus Spirit—Need for Changes path is not statistically significant, indicating that the variable has no impact on assessing the need for changes on campus. The atmosphere of the campus and its historical character do not influence the Need for Change in campus urban design. Similarly, the assessment of campus architecture and connections with the campus do not affect this variable. The campus assessment is not influenced by whether someone works at the university, has graduated, or lives nearby. The Campus Infrastructure is the most important factor influencing the assessment of the Need for Change. Among the directly measured variables, the most important are Accessibility and Convenience of Space Use (β = 0.618) and the Quantity and Quality of Green Areas (β = 0.553), followed by Architectural Aesthetics (β = 0.353), Infrastructure for Pedestrians and Cyclists (β = 0.276), and Spatial Layout and Building Functionality (β = 0.235). The model indicates that emphasis should be placed on improving campus infrastructure, as this is expected by the university community.

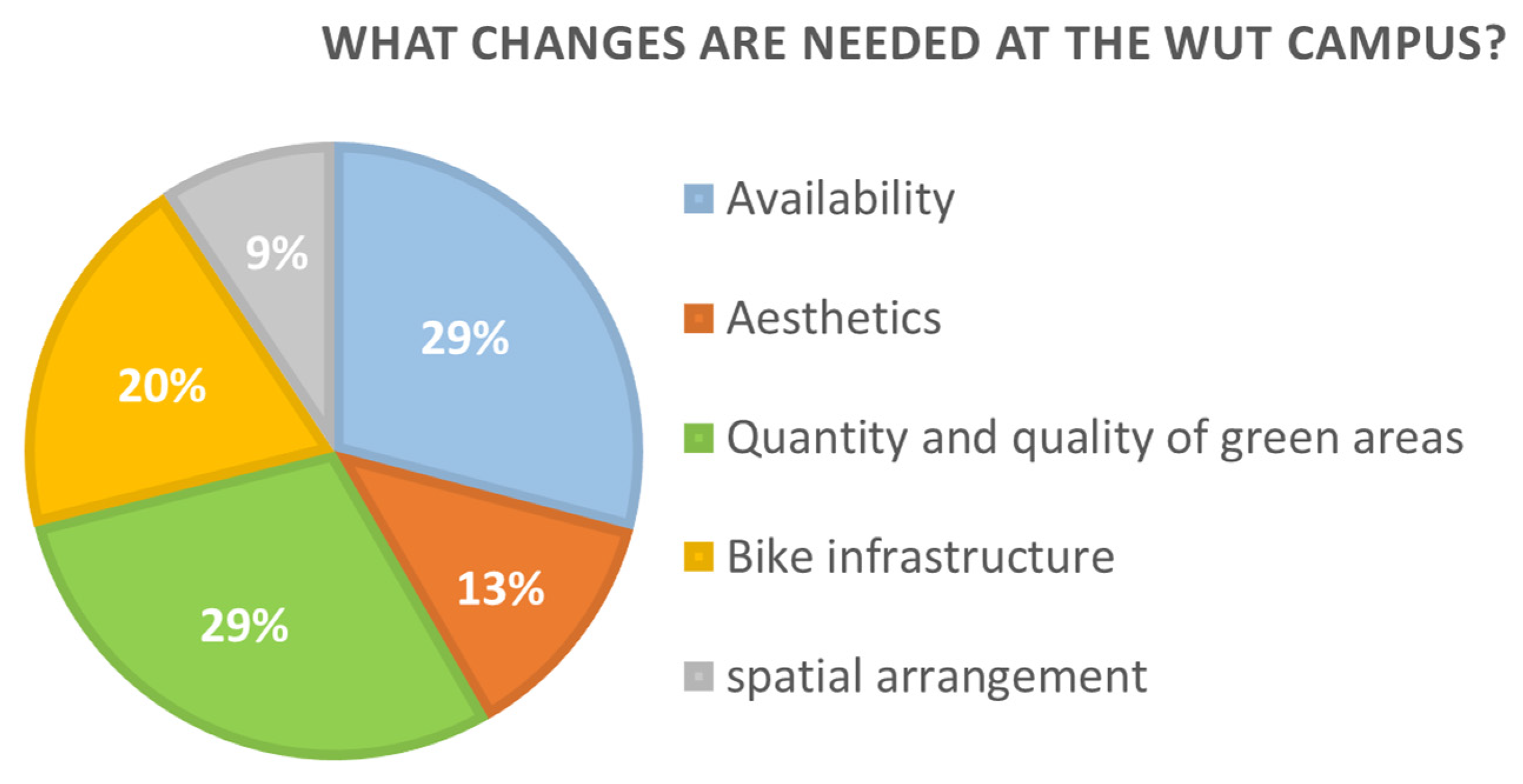

Although the perceived need for change is similarly strong among students (77%) and staff (75%), their priorities often diverge (

Figure 5). Improved accessibility and the quality of green areas are the most frequently cited directions for change (both at 29%). However, greenery is mentioned as a key issue by 34% of staff members, compared to only 27% of students. This difference may reflect distinct patterns of campus use: for staff, the campus is a space of prolonged presence and the need for regeneration, whereas for students, it is more often a space of transit. Conversely, the spatial arrangement of buildings is of interest to 11% of students but only 2% of staff. This may indicate differing perceptions of the potential for transformation, as younger users tend to view the space as more open to change.

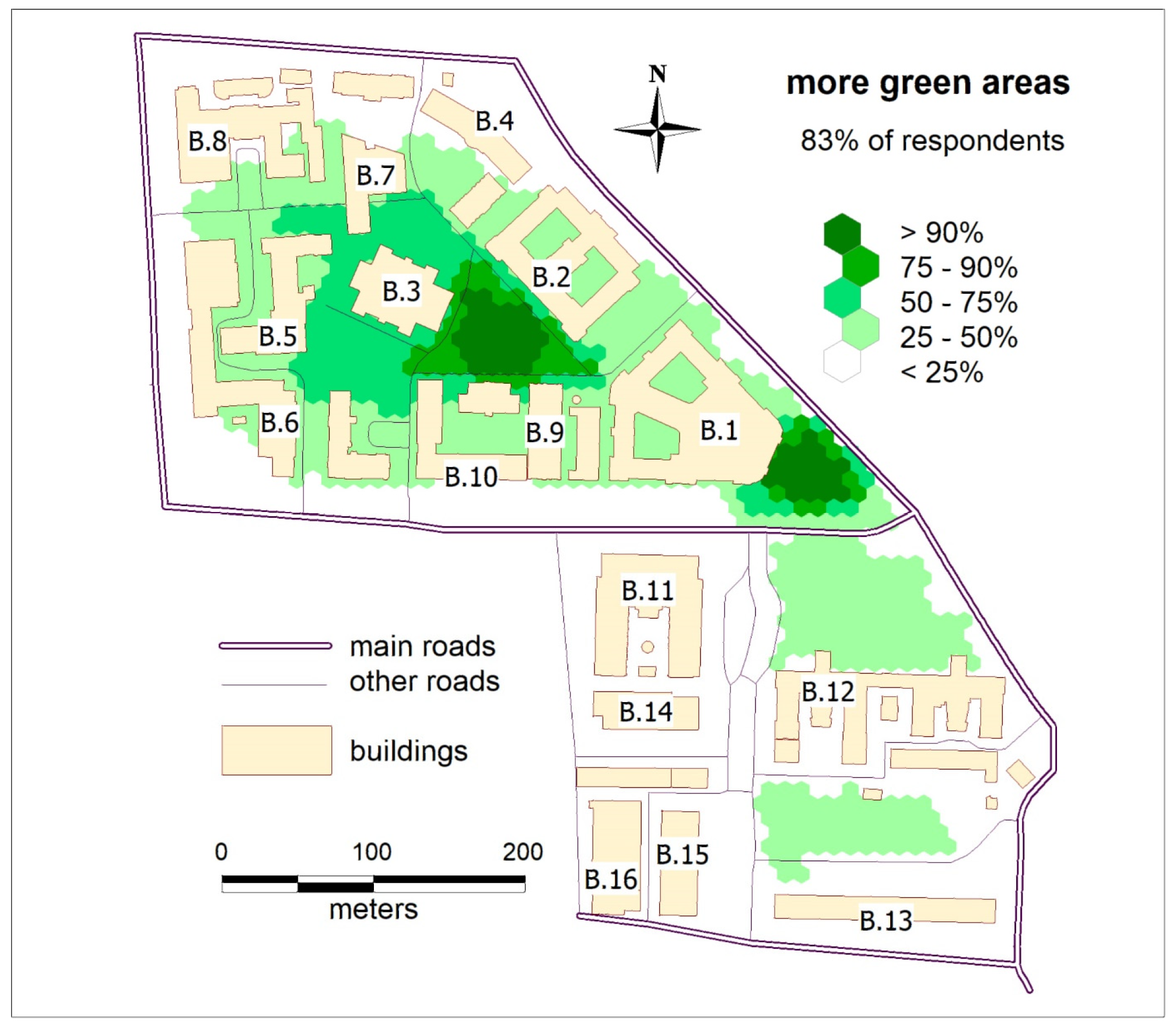

In other aspects, there is a relative consensus: around 20% of respondents call for the expansion of cycling infrastructure, and 13% point to the need to improve the campus’s aesthetics. Greenery emerges as a central theme: 29% of the respondents identify it as the most important issue (

Figure 6), and in the spatial section of the geo-questionnaire, as many as 83% mark it on the map as a topic requiring intervention. Thus, greenery is not merely an aesthetic demand but a symbol of the quality of life and spatial accessibility.

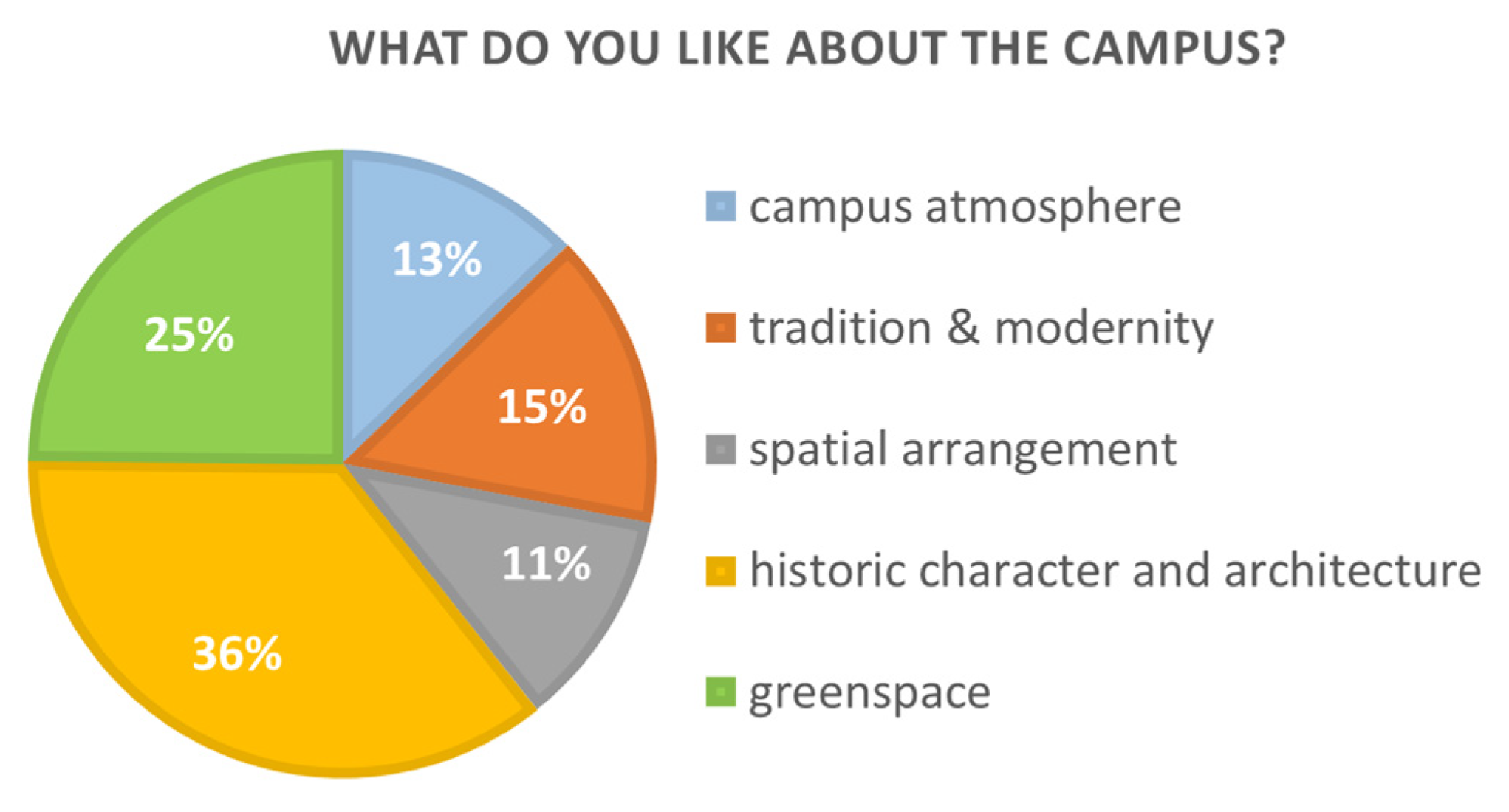

It is worth noting that declaring a desire for change on campus is not incompatible with recognizing the advantages of the current situation (

Figure 7). Notably, 36% of respondents appreciate the historical character of the university and its historic architecture, while 15% point to the successful combination of tradition and modernity. One in four respondents considers greenery to be the greatest asset of the campus, and 13% appreciate its atmosphere. Thus, the WUT campus is perceived both as a space of value (symbolic roots) and as a functional infrastructure in need of modernization.

6. Exploratory Analysis of Spatial Data

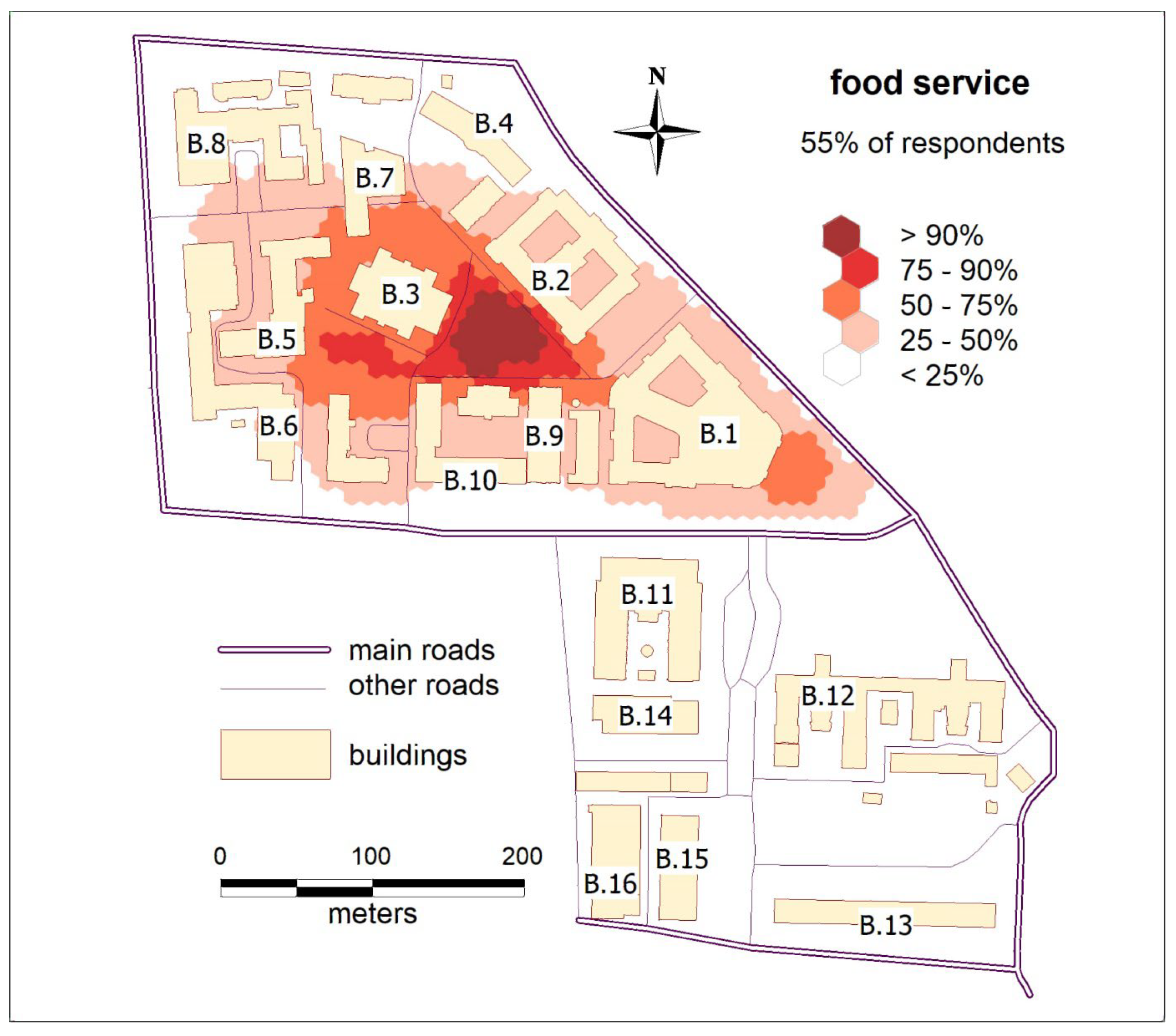

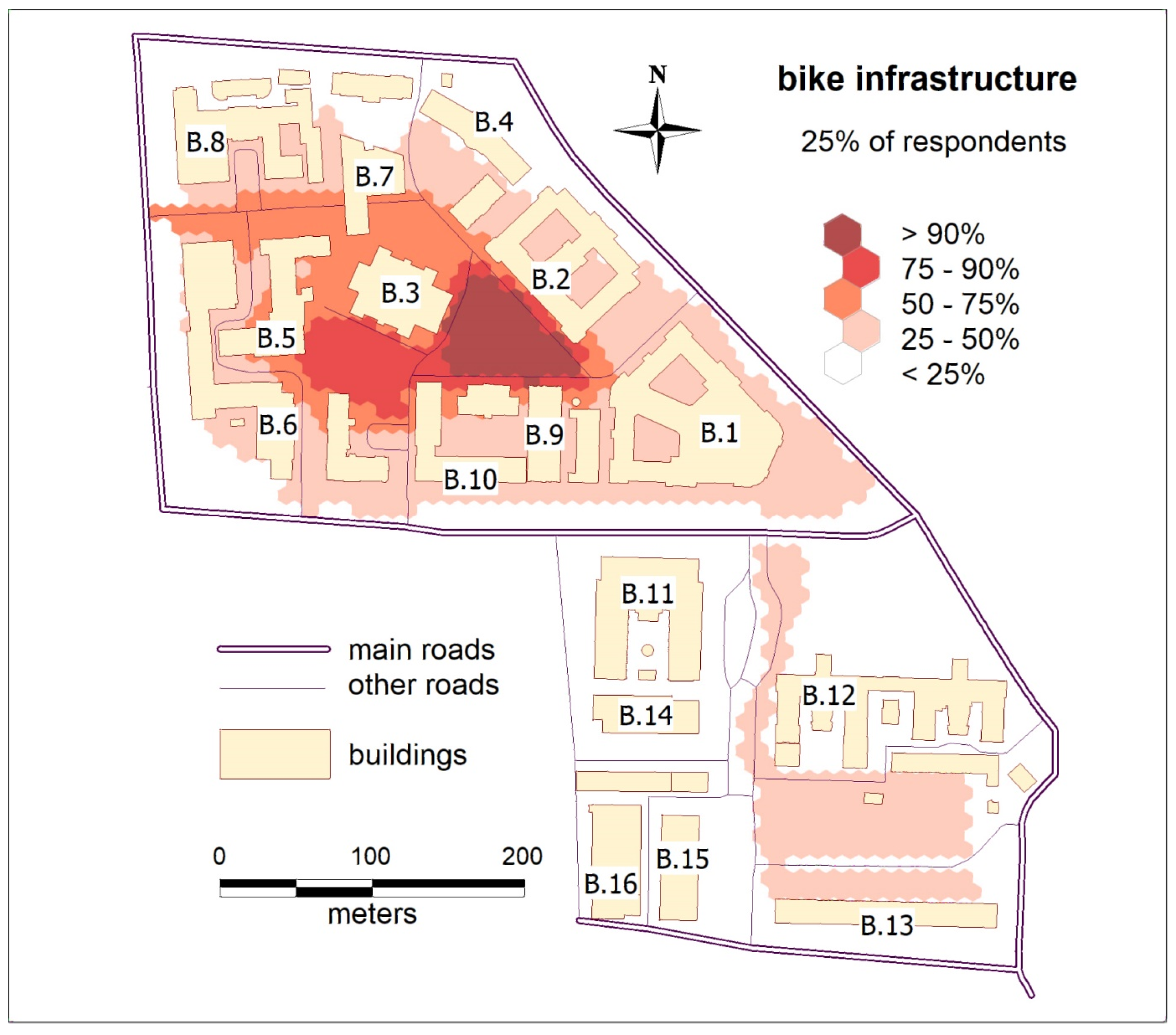

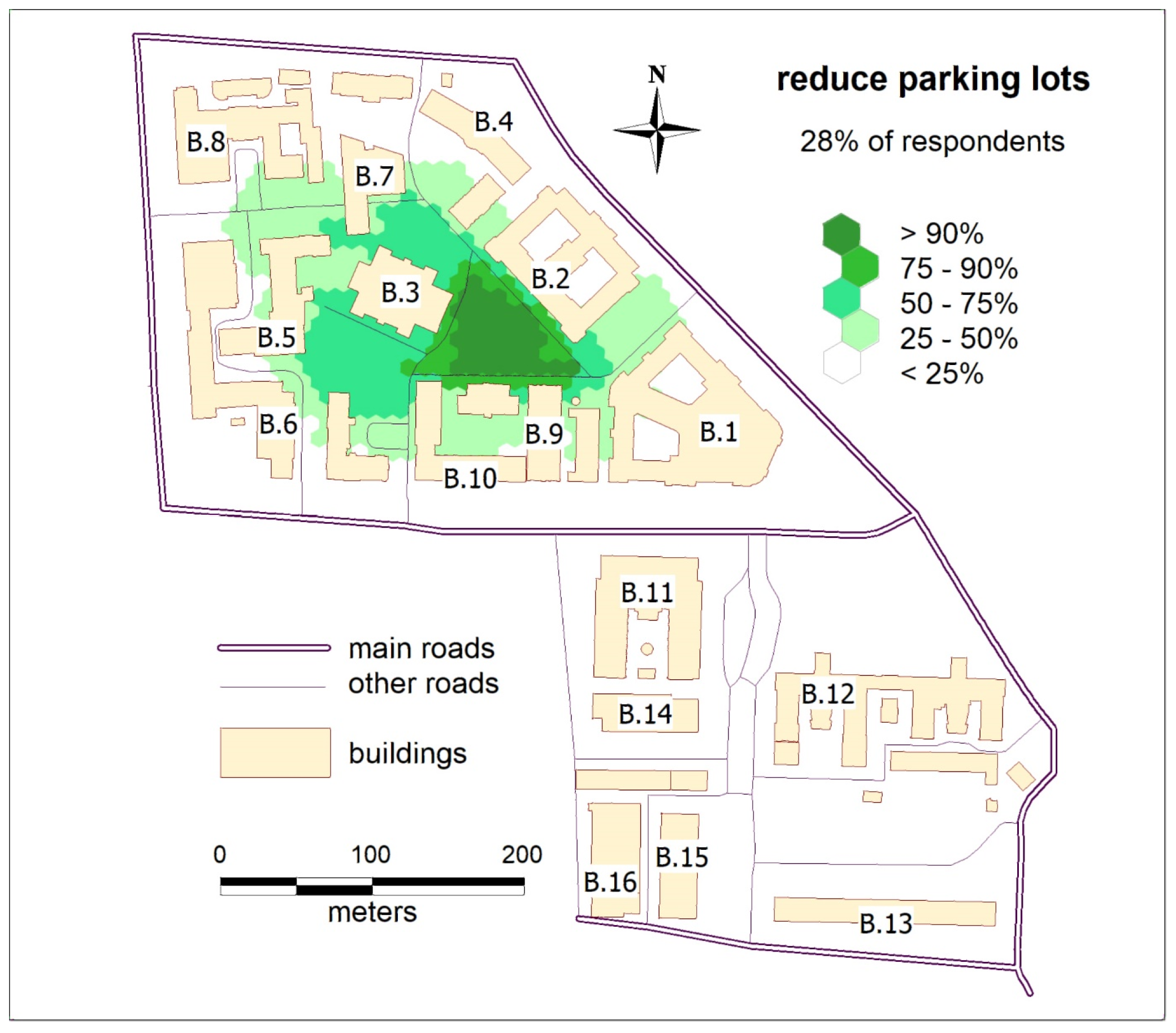

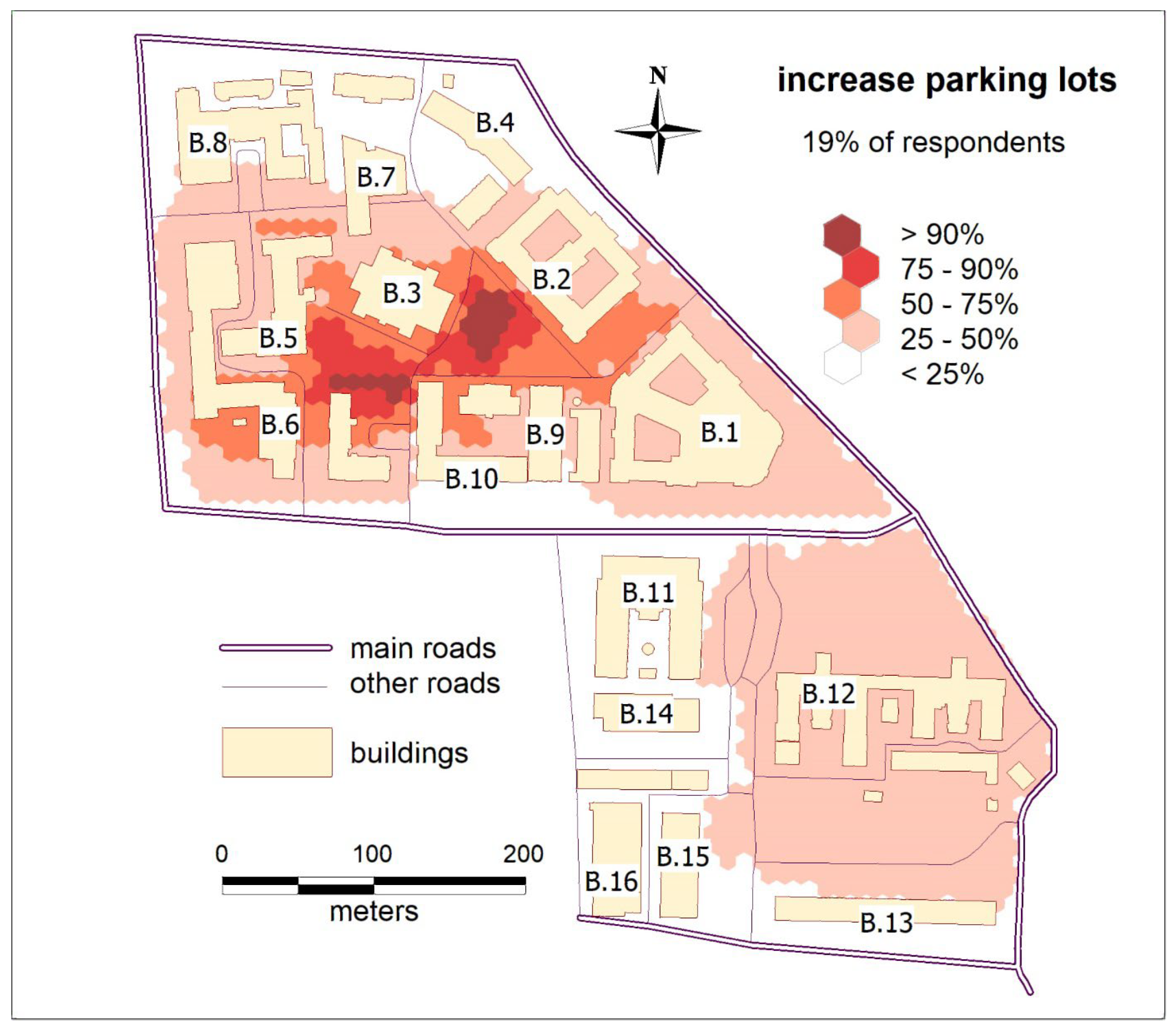

Due to the nature of the research and the use of social geoparticipation methods, specifically a geo-survey, analyzing the spatial distribution of the respondents’ declared need for change is crucial for understanding their opinions. Using geospatial tools, the participants drew on a base map to define the area for which they proposed a specific change, such as increasing the number of restaurants in the area or expanding the cycling infrastructure. Some respondents indicated several problems in the marked areas. At the same time, most drew independent ‘colored spots’ on the map for areas which, in their opinion, should be used, for example, to reduce the number of parking spaces or enlarge car parks. The geo-survey mechanism developed allowed users to draw any number of areas of any shape and size. The spatial database collected nearly a thousand areas of various sizes, indicated by respondents. The collected data were analyzed using GIS tools. To understand the spatial distribution of respondents’ opinions and the intensity of indications related to a specific location, a grid of 2131 hexagons, each with an area of 100 m

2 (1 are), was superimposed on the campus area of approximately 21 hectares. For each regular hexagon, the number of areas of a given type (e.g., more green areas—

Figure 7) drawn on the base map by respondents was determined. The results obtained were divided into five classes with varying degrees of intensity indicated by the respondents. The lowest class included hexagons that were indicated by less than 25% of respondents, while the highest class included those indicated by more than 90% of respondents. It should be emphasized that the percentages were determined independently for each problem (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). This means that the five-point color scale for each map indicates the relative interest in a given hexagon by respondents interested in a given problem. The metric characterizing the absolute interest in a given problem is the percentage of respondents who marked at least one area related to that topic on the map. For example, the problem of insufficient green areas on campus was important for as many as 83% of respondents (

Figure 8). In comparison, the problem of insufficient catering facilities was important for 55% of respondents (

Figure 9), and the problem of cycling infrastructure was important for 25% (

Figure 10). To emphasize this diversity, the map (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) features an increasing level of color intensity on a five-point color scale (as respondents’ interest in a given topic decreases).

The dominant problem, which was significant for over 80% of respondents—including employees, students, and visitors to the WUT campus—is the insufficient quantity and quality of green areas (

Figure 8). The vast majority of those who pointed to this issue highlighted the central area of the campus between the Main Building (B.1 on the maps), the Faculty of Chemistry (B.2), the Faculty of Physics (B.3), and buildings B.9 (Mechanics Building) and B.10 (Faculty of Environmental Engineering). This area currently serves as a tree-lined square, but it is surrounded by streets and pavements where cars are parked (

Figure 2b). There are not enough benches here, and cars parked on the pavements force pedestrians to walk on the lawns or the street. Respondents would like to see this square enlarged to include the area around the Faculty of Physics (B.3). Respondents also pointed to the problem of a lack of greenery at Plac Politechniki (the Polytechnic Square) (

Figure 2a), adjacent to the Main Building (B.1) on the south-east side. This place, traditionally called the ‘Rector’s Jaw’ due to its specific shape, used to serve as a car park, but now it is a representative and completely empty square with just a few small trees.

It should also be noted that respondents indicated that the park in front of the Faculty of Electronics building (B. 12), which lacks benches, is problematic. A significant proportion of respondents also believe that it would be advisable to convert the car park between the Faculties of Electronics (B.12) and Civil Engineering (B.13) into a green area.

An analysis of the academic community’s needs regarding catering services is also interesting. This issue is important for 55% of respondents (

Figure 9). Most of them believe that small catering establishments (cafés, bars, food trucks) should be located in the central part of the campus. For some of the respondents, the appropriate place to expand the catering offer is also Plac Politechniki (the Polytechnic Square) in front of the Main Building (B.1). It should be emphasized that, unlike the map showing the lack of greenery (

Figure 8), the problem of catering facilities only concerns the northern part of the campus. The central WUT canteen (B.14) meets the catering needs of people associated with the southern part of the central campus.

Another issue of concern for 25% of respondents is the insufficiently developed cycling infrastructure (

Figure 10). This problem affects almost the entire campus to varying degrees. As with other topics, respondents identified the central ‘triangle’ between B.1, B.2, B.3, and B.9 as key, but almost equally intense indications concern the western part of the campus. Respondents would like to see the development of bicycle paths near the Electrical Engineering Building (B.5), Faculty of Mathematics (B.7) and the Chemical Technology Building (B.8). Members of the academic community also pointed to the southern part of the campus, where makeshift and poorly constructed car parks between B.12 and B.13 make it difficult to ride and park bicycles.

One of the most interesting aspects of the research is the analysis of the parking needs of the WUT academic community. This issue is important for almost 30% of respondents. A significant proportion of them (

Figure 11) would like to see a reduction in the number of parking spaces in the central part of the campus, i.e., on the streets and pavements surrounding the centrally located triangular square. Some of the respondents would also like to see a reduction in the parking area around the Faculty of Mathematics (B.3). It is interesting to note that the car parks located in the southern part of the campus, occupying a significant part of the space between B.11, B.12, B.13, B.14 and B.15, do not raise any objections among the respondents.

Similar conclusions can be drawn from an analysis of the map, indicating the need to increase the number of parking spaces on the WUT campus (

Figure 12). Practically the entire southern part of the area has been designated as a parking area. However, some respondents believe that the northern part of the campus could also be used as an extended parking area. The respondents indicated the area in front of the entrance to the Physics Building (B.3), as well as the Electrical Engineering Building (B.5), the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering (B.6) and the Faculty of Environmental Engineering (B.10). Some respondents also felt that parking should be reinstated on Plac Politechniki (the Polytechnic Square) in front of the Main Building (B.1). However, it should be noted that the issue of increasing the number of parking spaces (

Figure 12) was important only for 19% of respondents, while the issue of reducing their number (

Figure 11) was important for 28% of them.

7. Discussion

The analysis of the results obtained indicates a high level of interest in the revitalization of the central campus of the WUT among members of the university’s academic community. The significant number of surveys collected (710) and the diverse thematic and spatial responses of the respondents indicate a high level of engagement on their part. Students, academic staff, and visitors to WUT identified the most important problems of the campus in a similar way. The analysis of spatial data obtained through the use of a geo-survey is particularly valuable in terms of knowledge. The spatial diversity of the responses obtained allows us to see not only what is important to the participants in the study, but also to locate them in a specific place on the campus. A cursory assessment of the results obtained could lead to the conclusion that the respondents want everything at once and that their expectations are contradictory. However, a deeper analysis of thematic maps indicates the rationality of the average opinion of the academic community. The central part of the campus and the triangular square around the (inactive) fountain constitute the heart of the university (

Figure 2b), where the respondents would like to see a functional park with small catering facilities. The square in front of the university’s Main Building, currently a concrete desert, should play a similar role. At the same time, respondents do not want to reduce the number of parking spaces in the southern part of the campus, while expecting the expansion of bicycle paths in this area. The central canteen provides wide access to catering services in the south, so respondents expect small eateries (or at least food trucks) in the northern part of the campus. This issue will be the subject of further research.

Therefore, a holistic spatial analysis of the survey results indicates that the expectations of the WUT academic community are reasonable and that it is possible to meet their needs. Naturally, when planning the revitalization of the campus to mark the university’s 200th anniversary, financial possibilities and applicable legal regulations must also be taken into account.

The social participation methodology proposed in the article can be applied to university campuses due to the relative ease of obtaining respondents’ opinions expressed in geo-surveys. Applying this approach on a city-wide scale requires significant activation of residents, which can be achieved through methods such as gamification and the use of serious games.

As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report [

68] shows, the effective implementation of digital participation—including geospatial participation tools—requires not only the right technologies, but above all a sustainable institutional and political framework that ensures the genuine inclusion of local communities in decision-making processes. The OECD identifies four key factors that promote effectiveness: clarity of objectives, transparency of processes, feedback loops for participants, and citizen agency. The absence of these conditions often leads to superficial participation practices in which residents are treated as a source of data rather than as equal co-creators of space.

To overcome these barriers, a multi-stage approach based on building trust, inclusiveness, and recognition of situated knowledge as equivalent to expert knowledge is necessary [

16]. There is also a need to diversify participation channels—by integrating digital consultations with offline activities, local animation, the use of community leaders, and communication support for digitally excluded groups (OECD, 2020 [

68]). Only then is it possible to truly democratize the planning process and overcome the asymmetry of knowledge and power in urban space [

17].

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research on campus spatial organization and user experience. Similar relationships between accessibility, greenery, and perceived spatial quality have been identified in other university contexts. For example, studies by Zhang et al. [

53] and Liao & Zhu [

52] confirm that walkability and the presence of green areas significantly enhance user satisfaction and well-being on campus. Moreover, research by Aghabozorgi et al. [

47] and Lau et al. [

48] demonstrates that natural environments and open-space design support users’ mental health and social interaction, aligning with the results obtained for the university. The observed importance of accessibility and green infrastructure also supports earlier findings by Hopff et al. [

46] and Mosca et al. [

55], who highlight that inclusive and sustainable design strategies improve both functionality and equity in university environments. Thus, the Warsaw University of Technology case confirms broader global tendencies toward greener, more inclusive, and pedestrian-oriented campuses.

It is worth noting that the results obtained may serve as recommendations for decision-makers and planners on how to implement the Digital Agora methodology on other university campuses and in cities. The implementation of these solutions would also ensure the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, with a particular emphasis on the role of geoparticipation in shaping inclusive, resilient, and sustainable cities. It should be emphasized that the issue of taking into account the requirements of sustainable development requires not only activity on the part of universities, but above all, education at the school level. By embedding sustainability in education from an early age, schools can cultivate informed communities that contribute significantly to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 11, ultimately positioning themselves as essential pillars of sustainable urban development. “The concept of pragmatic sustainability emphasizes the importance of practical approaches to environmental stewardship, making sustainable communities within schools vital for fostering responsible citizenship.

8. Conclusions

Academic campuses, thanks to their compact structure and strong symbolic ties, can serve as pilot environments (Living Labs) in which innovative models of spatial participation are tested. The solutions applied here, if effective and adequately adapted, can serve as a starting point for creating participatory planning models in more complex and diverse urban environments.

The use of social geoparticipation tools also helps to activate the academic community and brings the idea of the Digital Agora to life. Extensive, transparent research into the needs and expectations associated with the use of shared space is the first step towards managing this space using deliberative democracy methods. This is much easier on a university scale than on a city or national scale. A university campus is a kind of Living Lab where technological solutions facilitating the development of smart cities are tested. However, a university campus can also serve as a Living Lab for the application of geoinformation tools to the process of social geoparticipation and the participatory development of open common spaces. Examples obtained on the campuses of leading universities can be not only a contemporary realization of Plato’s Academy, but also an implementation of the idea of the Athenian Agora. A Digital Agora, using modern geoinformation technologies—serious geogames, geoinformation applications dedicated to mobile devices, or geo-surveys—can enable participatory planning and spatial development, both on a campus scale and on a national scale.

However, it is worth remembering that participation alone—even if technologically advanced—does not guarantee spatial justice if its results do not have a tangible impact on design decisions. It is therefore crucial not only to gather the community’s voice but also to effectively take it into account in decision-making and implementation processes. The methodology used—combining a geo-survey, spatial analysis, and a deliberative approach—can serve as a model for other universities planning spatial transformations. It shows that, with the use of available geoinformation tools and participatory strategies, it is possible to effectively involve the academic community in the design of the shared space. In this sense, the Warsaw University of Technology campus can serve as a laboratory for social and spatial innovation, as well as a model for institutions striving for a more inclusive, democratic, and equitable academic environment.

The methodology proposed in the article supports the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by fostering inclusive urban governance through social geoparticipation. By integrating community feedback and leveraging volunteered geographic information (VGI), the approach addresses spatial inequalities and enhances accessibility and green infrastructure—key indicators for sustainable urban development (SDG 11). The empirical findings highlight the community’s demand for improved green spaces, reinforcing the role of educational institutions as catalysts for change. This transferable methodology not only informs sustainable design practices at the campus level but also serves as a practical guide for broader city-scale revitalization efforts, promoting holistic and responsible community engagement in alignment with the SDGs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W., P.P. and R.O.; methodology, A.W. and R.O.; software, H.Ś.; validation, A.W. and K.E.; formal analysis, K.E. and K.K.; investigation, A.W., R.W., K.K., K.E., H.Ś., U.S.-B., P.P. and R.O.; resources, R.W.; data R.W. and H.Ś.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W., R.W., K.K., K.E., H.Ś., U.S.-B., P.P. and R.O.; writing—review and editing, A.W.; visualization, R.O.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, A.W.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Digital Europe programme under the grant number No. 101100728, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland and Warsaw University of Technology under the grant number STRATEG II CPR-IDUB/155/Z01/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the completely anonymous nature of the tests conducted on members of the WUT academic community—including staff, PhD candidates, and students.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EBD | Evidence-Based Design |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| PD | Participatory Design |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| PPGIS | Public Participation Geographic Information System |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VGI | Volunteered Geographic Information |

| WUT | Warsaw University of Technology |

References

- Lefebvre, H. Le Droit à la Ville; Anthropos: Paris, France, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J.A. Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution recognition participation. In Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Fraser, N., Honneth, A., Eds.; Verso: London, UK, 2003; pp. 7–109. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. New Left Rev. 2008, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Revised edition; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Purcell, M. Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant. GeoJournal 2002, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Li, H. Web-based participatory GIS for urban planning and community decision-making. Int. J. E Plan. Res. 2012, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, I.; van der Spek, S.; Beekhuizen, J. Using VGI and space syntax for inclusive campus design: A case study from Groningen. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2019, 8, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Jones, R.; Karvonen, A.; Millard, L.; Wendler, J. Living labs and co-production: University campuses as platforms for sustainability science. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, C.; Mirri, S.; Menarini, M.; van Steen, M. Mapping indoor spaces through gamification: The Campus-Mapper project. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 82, 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadas, S.; Hossain, M.; Rahimi, M. Integrating VGI into resilience planning: A scalable framework. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 2123–2141. [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg, S.; Horst, M.; O’Donovan, C.; Bombaerts, G.; Hansen, M.; Takahashi, M.; Viscusi, G.; Ryszawska, B. University Campus Living Labs: Unpacking Multiple Dimensions of an Emerging Phenomenon. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 37, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities in the 21st Century; Continuum: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, R.; Wendland, A. Digital Agora—Knowledge acquisition from spatial databases, geoinformation society VGI and social media data. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A. Living Laboratories for Sustainability: Exploring the Politics and Epistemology of Urban Transition. In Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ducci, M.; Janssen, R.; Burgers, G.-J.; Rotondo, F. Mapping Local Perceptions for the Planning of Cultural Landscapes. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2023, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsia, E.; Nummi, P. Beyond the Blind Spot: Enhancing Polyphony Through City Planning Activism Using Public Participation GIS. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A.; Chappin, E.J.L.; van Dam, K.H. Integrating agent-based modeling, serious gaming, and co-design for planning transport infrastructure and public spaces. Urban Des. Int. 2021, 26, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, B. Game-based public engagement in city-making: Minecraft as a participatory platform. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, L. Gentrification and Social Mixing: Towards an Inclusive Urban Renaissance? Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 2449–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaha, E.; Alsyouf, I.; Hamad, R.; Elmualim, A.; Maksoud, A.; Yahia, M.W. Developing design guidelines for university campus in hot climate using Quality Function Deployment (QFD): The case of the University of Sharjah, UAE. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2022, 18, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Haque, M. Campus Commons: Analysis of IIT Patna’s Public open Spaces. Qubahan Acad. J. 2024, 4, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducci, L.; Salvati, L.; Romano, B. Geo-participation in rural spatial planning: A case study using Maptionnaire and participatory mapping. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106678. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Lehmann, M.; Scholz, R.W. Co-designing mobility futures using serious games and agent-based modeling. Futures 2021, 132, 102810. [Google Scholar]

- Szarek-Iwaniuk, P.; Senetra, A. Access to ICT in Poland and the co-creation of Urban space in the process of modern social participation in a smart city-a case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, N.; Elnokaly, A.; Mills, G. The role of a university in city transfromation. In Proceedings of the 12th International Space Syntax Symposium, Beijing, China, 8–13 July 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, S.; Sharr, A. The University of Nonstop Society: Campus Planning, Lounge Space, and Incessant Productivity. Archit. Cult. 2021, 9, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlenz, M.M. The university and its neighborhood: A study of place-making and change. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.; Powers, M. Before the Neoliberal Campus: University, Place and the Business of Higher Education. Archit. Cult. 2021, 9, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terro, M.J.; Soliman, A.M.; Angell, J. Taxonomy of Tertiary Education Campus Planning. J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidou, C.; Gugerell, K.; Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Jauschneg, M.; Berger, M. All work and no play? Facilitating serious games and gamified applications in participatory urban planning and governance. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, M.; Jackowski, S.; Matysiak-Rakoczy, K. Przestrzenie Uniwersytetu: Trendy, Wizje Projektowania; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, C.M.; Do, A.; Elayan, S.; Feick, R.; Gruebner, O.; Rank, E.; Shaughnessy, K.; Sheppard, H.; Solter, M.; Sykora, M.; et al. Smart Citizens Enabling Resilient Neighbourhoods (SCERN): Participatory mapping platform for resilience planning at a neighbourhood scale. Cities 2025, 165, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbert, M. The campus and the city: A design revolution explained. J. Urban Des. 2019, 23, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, N. The university within, of and for the city: Reflections on the entanglement of academic practice and the local. Local Gov. Stud. 2024, 50, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, R.; Pullan, N.; Saniga, A. The making of a city campus. Geogr. Res. 2021, 59, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perondi, E. The Role of the University Campus in the Local Sustainable Economic Development. In Universities as Drivers of Social Innovation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Rezaei Liapee, S.; Mohajer, M. The Role of Sense of Belonging to the Architectural Symbolic Elements on Promoting Social Participation in Students within Educational Settings. Space Ontol. Int. J. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Sprowles, A.E.; Goldenberg, K.R.; Margell, S.T.; Castellino, L. Effect of a Place-Based Learning Community on Belonging, Persistence, and Equity Gaps for First-Year STEM Students. Innov. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopff, B.; Nijhuis, S.; Verhoef, L.A. New Dimensions for Circularity on Campus—Framework for the Application of Circular Principles in Campus Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabozorgi, K.; Jagt, A.V.D.; Bell, S.; Smith, H. How university blue and green space affect students’ mental health: A scoping review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 97, 128394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y. Healthy campus by open space design: Approaches and guidelines. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.; Santana, K.V.D.S.; Oliver, S.L. Natural Environments in University Campuses and Students’ Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croog, R. Campus sustainability at the edges: Emotions, relations, and bio-cultural connections. Geoforum 2016, 74, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousighichi, P.; Mousavi Samimi, P.; Mousapour, B. Impact of biophilic design parameters on university students’ place attachment and quality of campus life. J. Archit. 2024, 29, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Zhu, J. Exploring the Causal Relationship between Walkability and Affective Walking Experience: Evidence from 7 Major Tertiary Education Campuses in China. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L. Examining non-linear relationships between campus layout, street design, and walking activity. Transp. Policy 2025, 163, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, C.; Kondrashov, O. Universal Design on University Campuses: A Literature Review. Except. Educ. Int. 2019, 29, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mosca, E.I.; Crotti, G.B.; Capolongo, S.; Buffoli, M. Universal Design in University Environments. Are the New Buildings More Inclusive? A Tool for Equal Design Assessment. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, P. Designing more effective on-campus teaching and learning spaces: A role for academic developers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2003, 8, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, C.B. O’Donnell and Tuomey’s University Architecture: Informal Learning Spaces that Enhance User Engagement. Archit. Cult. 2021, 9, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Kennedy, G. Issues and Ideas Paper The Value of Campus in Contemporary Higher Education; Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.; Mahat, M.; Tregloan, K.; Rivera-Yevenes, C.; Lomer, S.; Cockayne, H.; Zhang, A.Y. Exploring the meaning of campus through lived experiences of students, staff, and visitors. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2025, 44, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, L.C.; Hajrasouliha, A.H.; Riggs, W.W. State of the Art in Planning for College and University Campuses: Site Planning and Beyond. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2018, 84, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewski, K.; Olszewski, R.; Pałka, P.; Walczak, R.; Korpas, P.; Dąbrowska-Żółtak, K.; Wyszomirski, M.; Czeranowska-Panufnik, O.; Manujło, A.; Szczepankowska-Bednarek, U.; et al. Utilizing IoT Sensors and Spatial Data Mining for Analysis of Urban Space Actors’ Behavior in University Campus Space Design. Sensors 2025, 25, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanoff, H. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wendland, A.; Samociuk, K.; Szalwa, A.; Arruti, I.B.; Szczepankowska-Bednarek, U.; Wesołowski, J.; Wnuk, J.; Olszewski, R. Campus Changer—A serious geogame for transforming the Main Campus of the Warsaw University of Technology. Urban Plan. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Manifesty, O.R.; Lee, J. A Spatial Adaptation Strategy for Safe Campus Open Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Korea University. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurahaju, R.; Widanti, N.S. Model Analysis of Student Satisfaction Based on Campus Image and Quality of Service. J. Educ. Pract. 2021, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; p. 363. ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Development Co-operation Report 2020. Learning from Crises, Building Resilience. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/development-co-operation-report-2020_f6d42aa5-en.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).