1. Introduction

The construction sector has long been one of the most accident-prone areas of economic activity, with consistently higher accident rates than other industries [

1,

2]. This is due, among other things, to the diversity of professions, materials, and construction equipment [

3]. According to data from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) [

4], on average, there are approximately 60,000 fatal accidents at work on construction sites worldwide each year. On average, this means that one fatal accident occurs approximately every ten min. In industrialised countries, as many as 25–40% of all fatal accidents at work occur on construction sites, even though this sector employs only 6–10% of the workforce in each country [

4]. A similar pattern [

5] can also be observed in countries around the world, including China, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Australia, and South Korea.

Although approximately USD 1.8 billion is spent annually on workplace safety audits and inspections, and the construction worker safety market is valued at around USD 3.5 billion in 2025 [

6,

7], accident rates remain high due to limited inspection frequency and human error, emphasising the urgent need for automated hazard detection systems.

Accidents at work and other dangerous incidents in construction generate significant material losses that burden not only companies but also entire societies. These costs include both direct expenses related to the treatment and rehabilitation of injured persons and indirect losses resulting from work stoppages, loss of productivity, and compensation payments [

8,

9]. The costs of accidents at work can place a significant burden on the budgets of companies and insurance institutions [

10]. For example, in Poland alone, the estimated material losses caused by accidents at work in the period 2015–2022 amount to approximately USD 3.75 million [

11]. However, it is worth noting that the losses associated with pain, suffering, and reduced quality of life for both the injured person and their family are practically impossible to estimate. In view of these devastating statistics, improving safety at work in the construction industry is now becoming a key priority [

12]. One of the most important preventive measures aimed at improving the current unfavourable situation is the identification of the most common and most dangerous factors in the work process. These are the direct causes of accidents at work and near misses [

13,

14].

The results of previous studies indicate that one of the main causes of injuries and deaths in construction is falls by workers [

15,

16]. In a study conducted by Chi and Han [

17], 42% of 9358 accidents at work were caused by falls from height. Similar results were observed when analysing data from the Polish branch of one of the largest construction companies [

13], where it was found that 25.8% of accidents at work and 6.2% of near misses were incidents involving falls from height.

Another significant problem on construction sites is the failure of workers to use personal protective equipment [

18]. The link between the lack or improper use of such equipment (including safety helmets) and the occurrence of accidents at work has been confirmed in studies [

19]. An analysis of accident reports carried out by the authors clearly showed that the most dangerous incidents during work at height were directly related to the lack or incorrect use of protective equipment. Similar conclusions were presented by Polish researchers, who indicated that the failure to use personal protective equipment by employees was the cause of approximately 20% of accidents related to work on construction scaffolding [

20].

In recent years, the automation of occupational safety monitoring through computer vision and artificial intelligence has gained significant attention. Numerous studies have focused on detecting the absence of personal protective equipment (PPE) or identifying unsafe worker behaviours using deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and real-time object detection frameworks such as YOLO, SSD, or Faster R-CNN. These approaches have demonstrated high accuracy in controlled or simulated conditions; however, their implementation on real construction sites remains limited due to high computational demands, lack of integration capabilities, and difficulties in adapting to variable lighting and environmental conditions.

In response to the identified problems related to work safety on construction sites, this article presents an original approach using machine learning algorithms and advanced image and data analysis techniques. The aim of the research conducted and presented in this paper was to develop a comprehensive system integrating automatic detection of key hazards and dangerous events occurring on construction sites with the functionality of monitoring them and generating alerts about identified events. The proposed solution, using machine learning algorithms, aims to identify health and safety violations, such as the failure of construction workers to wear protective helmets, and to detect potential hazards and incidents related to worker falls at an early stage. The proprietary system also enables automatic notification of the relevant supervisory services on the construction site about any dangerous events, which improves the response to hazards and supports rapid rescue operations.

The prototype developed in this study aims to address these challenges by employing a lightweight YOLOv8s model, which ensures real-time performance without the need for high-end hardware. Combined with a simple web-based interface and an open API, the system provides a flexible foundation for further research and development of affordable and easily deployable safety monitoring tools for small and medium-sized construction enterprises. According to the authors, the developed system can contribute to a significant reduction in the number of accidents at work, especially those with the most serious consequences. Consequently, the developed system not only addresses the practical need to improve safety on construction sites but also supports the implementation of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) defined in the United Nations 2030 Agenda [

21]. In particular, it contributes to Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by reducing the number of accidents and improving workers’ well-being; to Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by minimising economic losses resulting from downtime and accident-related disruptions; and to Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) by promoting the adoption of modern information technologies in the construction sector [

21]. In a broader perspective, the development of such AI- and image-analysis-based solutions supports the ongoing digital transformation of the construction industry and contributes to creating safer, more resilient, and sustainable working environments, consistent with the directions highlighted in recent reports on SDG progress [

22].

Despite substantial progress in YOLO-based PPE and fall-detection models, existing studies typically deliver stand-alone detection modules without integration into end-to-end systems capable of alerting, event registration, or low-latency deployment on resource-constrained devices. This limits practical adoption, as the safety impact depends on complete supervisory workflows rather than detection alone. The present study addresses this gap by demonstrating a lightweight, fully integrated system architecture that connects detection, alerting, and incident traceability within a unified, API-driven framework.

Based on the identified research gap, the main objective of this study is to design and experimentally evaluate a prototype system for the automatic detection of key safety hazards on construction sites using computer vision and deep learning methods. Additionally, the study includes a comprehensive literature review aimed at consolidating current findings and positioning the proposed solution within the broader research landscape. From a technical perspective, the research addresses several important challenges related to the development of AI-based detection systems, including the need to ensure reliable real-time performance, achieve accurate classification with limited training data, and integrate detection, alerting, and event recording within a unified modular architecture. Accordingly, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How effective is the proposed YOLOv8-based model in detecting the absence of safety helmets and worker falls within the designed prototype system?

RQ2: How can detection, alert generation, and event recording be conceptually integrated through an open API to support real-time safety monitoring?

RQ3: What are the main factors influencing detection accuracy and system performance under test conditions, and how can they inform further development of the model and its architecture?

The article is organised as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of the literature in the field of OHS hazard detection methods based on deep learning algorithms, with a particular focus on YOLO (You Only Look Once) models.

Section 3 presents the proposed system architecture, including technological solutions, detection modules, and the API interface.

Section 4 describes the experiments conducted, the test environment configuration, and the system effectiveness evaluation procedures.

Section 5 contains an analysis of the results obtained, together with a comparison to existing solutions.

Section 6 presents the conclusions, while the following

Section 7 and

Section 8 discuss the limitations of the research conducted and indicate directions for further development of the system.

2. Literature Review

Work in the construction sector involves a high level of risk, which results, among other things, from the diversity of tasks performed, the technologies used, and the constantly changing conditions on the construction site [

23,

24,

25]. The scale of hazards in construction and the consistently high number of accidents at work indicate an urgent need to implement modern, automated, and precise systems to increase the safety of workers. Existing methods, based mainly on periodic inspections and reporting incidents after they occur, are proving insufficient in the context of the growing dynamics and complexity of modern construction processes. In response to these challenges, digital technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are playing an increasingly important role, enabling the implementation of systems that provide continuous monitoring of working conditions and immediate detection of potential hazards.

2.1. Real-Time Image Analysis

Current scientific forecasts indicate that in the coming years, the development of predictive technologies and systems using real-time data analysis will play a key role in improving safety indicators in the construction sector [

26]. Of particular importance in this context are advances in deep learning algorithms, including single-pass models such as YOLO, which have enabled significant improvements in the quality and performance of object detection in real-world environments.

The YOLO system is an advanced algorithm based on convolutional neural networks (CNN) for real-time object detection [

27]. Its application is crucial in many fields, such as autonomous vehicles, robotics, video surveillance, and augmented reality [

28]. YOLO algorithms are distinguished by their combination of high speed and precision, making them one of the most effective tools in this field [

29].

Since the introduction of the first version of YOLO v1 by Redmon et al. [

30] in 2016, the framework underwent several improvements [

31]. Subsequent iterations have consistently improved, among other things, detection accuracy, speed, and processing efficiency on various hardware platforms [

32]. Other important approaches have also been developed in the field of object detection, including R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) and its newer versions, Fast R-CNN and Faster R-CNN. Although these methods are highly accurate, their computational complexity limits their use in systems where real-time detection is crucial. Alternatives include SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) [

33] and RetinaNet [

34], algorithms that offer a compromise between speed and detection accuracy.

Despite growing competition, YOLO remains one of the most versatile solutions, widely used in both scientific research and industrial applications. Its architecture is easily adaptable to diverse environmental conditions, making it a suitable tool for hazard detection on construction sites and in occupational safety support systems.

2.2. The Use of Image Analysis Systems in Construction

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in interest in the use of modern technologies in the construction sector, including artificial intelligence algorithms [

35]. An example of such an application is the detection of damage during the inspection of damaged wind turbines using the YOLO algorithm [

36] or during bridge inspections to detect damage to bridge structures using migration learning techniques [

37].

In the field of occupational safety, one of the most promising areas of research is the use of image analysis techniques for the automatic recognition of dangerous behaviour by construction workers and violations of occupational safety rules. Thanks to the use of deep learning algorithms, especially convolutional neural networks (CNN), it is possible to detect situations such as the lack of protective clothing or harnesses [

27]. It is also worth noting research using YOLOv8 in combination with the ByteTrack algorithm to track and count objects on a construction site, which enables, among other things, automatic monitoring of the number of personnel, machines, and construction equipment [

38].

Recent research on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced computer-vision techniques for detecting irregularities in the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by construction workers has progressed significantly in recent years. We restrict our review to a selected set of representative vision-based studies on construction-site occupational health and safety (OHS), covering PPE compliance and fall detection.

Table 1 summarises the detection tasks and system-level capabilities, while

Table 2 extends the same entries with dataset sizes/splits, key performance metrics, applicable scenarios, and concise innovation notes.

Details for each study (dataset size and split, metrics, scenarios, and innovation highlights) are provided in

Table 2.

As presented in

Table 2, recent YOLO-based architectures demonstrate mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5) values ranging from approximately 84.7% to 93.2%, while maintaining real-time inference performance between 60 and 90 frames per second. Wu et al. [

39] proposed the most computationally efficient lightweight configuration, achieving 89 FPS. In contrast, studies such as those by Qin et al. [

41] and Huang et al. [

43] emphasised robustness in fall detection tasks, particularly under challenging visual conditions, including occlusion and variable illumination.

All the above approaches indicate the great potential of modern technologies in the context of preventive occupational safety management on construction sites, while emphasising the need for further improvement of algorithms and their adaptation to the specific nature of the construction environment. The above research also shows that the use of systems employing artificial intelligence algorithms can contribute not only to reducing the number of accidents at work, but also to improving the safety culture in construction organisations [

47]. However, the implementation of such solutions requires appropriate organisational preparation, including training for employees [

48] and the adaptation of risk management procedures to new technologies [

49].

As seen across

Table 1 and

Table 2, helmet-focused methods primarily exploit attention and small-object heads to cope with occlusion and low light, whereas fall-detection approaches favour lightweight backbones and tailored losses to recover recall in cluttered scenes. Dataset scales vary markedly (from 95 annotated frames to 103,500 images), limiting direct leaderboard-style comparisons and motivating a scenario-aware synthesis. Most prior studies optimise a single task and rarely report system-level features (event logging, open APIs). In contrast, our system jointly addresses two priority hazards (no-helmet and human falls) within a low-compute, asynchronous pipeline with a web UI, incident register, and open API, prioritising deployability on real construction sites.

Our decision to adopt YOLOv8 for construction-site safety analytics is motivated by peer-reviewed evidence. First, in a head-to-head comparison on identical helmet-detection data, Wang et al. [

50] reported that YOLO attained both the highest accuracy (mAP 53.8%) and the fastest inference (10 FPS) relative to SSD and Faster R-CNN, while on the CHV dataset the YOLOv5 family scaled from real-time (YOLOv5s, 52 FPS on GPU) to high-accuracy (YOLOv5x, mAP 86.55%), with quantified robustness limits under face-blurring/occlusion perturbations (≈7 pp AP drop for helmets). At the same time, Fang et al. [

51] demonstrated that two-stage Faster R-CNN is effective for non-hardhat-use detection on real sites, but with the characteristic throughput penalty of region-proposal pipelines. Beyond daylight conditions, Wang et al. [

52] showed that an improved YOLOX variant maintains strong performance for small PPE targets in low-illumination tunnel environments, supporting the family’s resilience to adverse lighting. Finally [

53], lightweight YOLOv5 modifications (e.g., pruned/attention-augmented YOLOv5s) have been validated on safety-helmet tasks, indicating suitability for resource-constrained deployments without forfeiting accuracy. In

Table 3, we summarise the comparative evidence and concise characteristics of the referenced methods.

2.3. Identified Research Gap and Research Objective

Despite the growing number of solutions using artificial intelligence algorithms to monitor occupational safety hazards, their practical implementation on construction sites faces numerous difficulties. The main barriers include the complexity of integration, the lack of standardised interfaces, and the limited availability of technology for smaller companies. The lack of simple and inexpensive systems that can be implemented in environments with limited technical resources is particularly acute.

Recent studies confirm that these challenges are not merely general observations but well-documented barriers in the implementation of computer vision systems for safety management in construction. Research to date [

26,

27] highlights the technical and organisational complexity of integrating AI-based detection modules with BIM, IoT, and site management platforms, largely due to the absence of standardised data exchange protocols and interoperability frameworks, which increases both the cost and the risk of deployment in heterogeneous environments. Furthermore, computational requirements and limited hardware capabilities remain a significant obstacle for small and medium-sized enterprises, as many high-performance AI models are unsuitable for real-time inference on low-cost edge devices. However, recent works demonstrate that lightweight architectures such as YOLOv8s or MobileNet variants can maintain adequate detection accuracy while significantly reducing resource consumption, thus enabling feasible on-site deployment [

43]. These findings reinforce the relevance of the proposed solution, which addresses the identified gaps by combining a lightweight detection model, open API integration, and event traceability mechanisms, ensuring both scalability and affordability for SMEs.

Unlike prior single-task YOLOv8 implementations, our system contributes a modular foundation in which detection, event logging, and alert propagation form a cohesive workflow. This foundation is required because current YOLOv8-based studies rarely address interoperability, real-time system latency, data persistence, or hardware-constrained deployment—all of which determine whether predictive or proactive safety modules can be practically introduced.

To address this research gap, a vision system based on the YOLO algorithm was designed to detect key hazards such as the absence of a safety helmet and employee falls. The developed system is also equipped with an open API and an incident recording module, enabling easy integration and documentation of events. Unlike previous single-task models, the proposed system integrates an open API, an incident-logging module, and a lightweight cloud architecture, forming a closed loop of ‘detection–alert–record–traceability’. Hardware requirements are reduced to ordinary edge devices, making the solution affordable for small and medium-sized contractors.

3. Materials and Methods

A schematic diagram of the research and development process for the developed system is presented in

Figure 1.

The system development process began with defining the general design assumptions, including its functionality, technical requirements, and available hardware and software resources. At this stage, it was assumed that the system should enable automatic detection of two key hazards to the safety of workers on the construction site:

If one of the above events is detected, the system should automatically record the incident in the database and immediately forward the relevant information to the supervisory team on the construction site (i.e., the site manager or health and safety inspector) by means of an appropriate alert. Additionally, it was assumed that the system would be able to integrate with the existing technical infrastructure via an API interface and operate via an intuitive web application.

In the next stage of the work, the system architecture was developed, covering both analytical components and technical infrastructure. The first step was to select a suitable real-time object detection algorithm. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) model was chosen, which, thanks to the use of deep neural networks, enables high detection accuracy with low computational delays. YOLOv8 was selected as the detection framework due to its stability and proven performance in industrial safety applications, which made it well-suited for the prototype implementation on low-cost edge devices [

46,

47].

For the system, functions were implemented to detect selected threats to work safety. These included the detection of the presence and colour of safety helmets (e.g., yellow, blue, white, or red) and the identification of situations indicating a person has fallen. These modules were integrated with the analytical part of the system, enabling automatic classification of events based on camera images.

At the same time, a cloud environment was configured, in which a database for recording detected incidents and disc space for storing video material and analysis results were launched. Communication between system components was also ensured through the implementation of a backend layer and the provision of an API interface. This interface enabled the transmission of images from surveillance cameras and integration with external administrative systems.

As part of the system development, an administrative panel accessible via a web browser has been envisaged. The user interface allowed for viewing recorded incidents, analysing statistics, and basic management of system parameters.

After implementation, functional tests were carried out in an environment similar to the real one. The tests included system initialisation, transfer of test images from cameras to the cloud, evaluation of the effectiveness of the detection algorithm, and the correctness of event recording.

3.1. Design Requirements

The design requirements for the proposed solution were divided into functional requirements (

Table 4) and technological requirements (

Table 5).

3.2. System Architecture

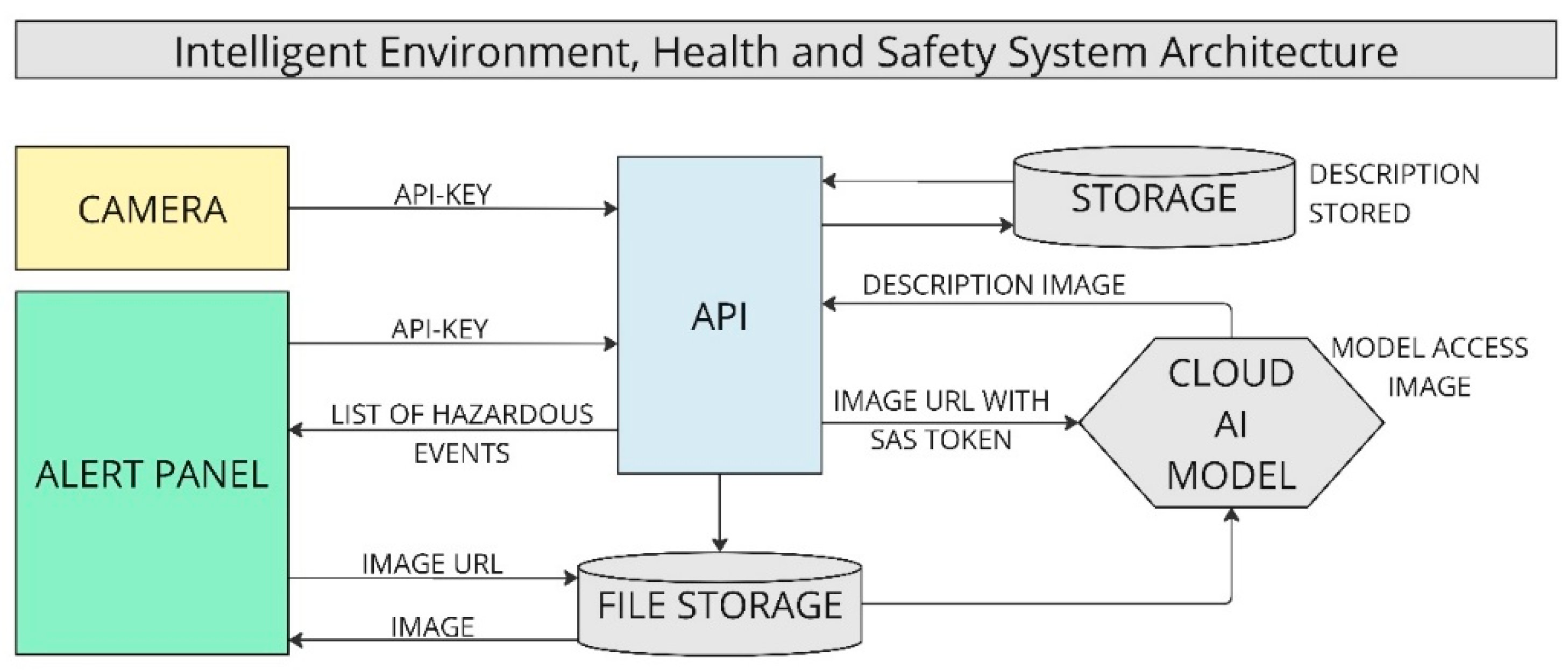

The data flow model developed in the proprietary construction site hazard detection system uses machine learning (ML) algorithms to analyse images in real time. The system aims to automatically monitor the working environment and identify potentially dangerous events based on defined behaviour patterns. The solution architecture includes key components such as a monitoring camera, an API programming interface, a data storage system, an ML model operating in a cloud environment, and an alarm panel. The data flow model is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The process begins with the acquisition of image data from a camera observing a specific workspace. Communication between system components is provided by an API, which acts as a central transmission hub. The API also authorises access to data using a unique identification key (API Key), which increases transmission security.

The API interface transmits image data and provides so-called descriptors containing important information necessary for further processing, including:

The location of files in the data store—images are stored on the server and accessible via unique URLs secured with a SAS (Shared Access Signature) token, enabling controlled and secure access;

Processing status—descriptors contain HasAlert and ResolvedAlert flags, indicating whether a potential threat has been detected and whether a given frame has already been verified by the system operator.

The developed system uses a RESTful API that enables communication between the monitoring module, the detection model, and the database. The communication between system components follows a sequence of asynchronous operations designed to ensure real-time performance and secure data handling.

The typical sequence of operations is as follows:

- (I)

Image acquisition: the camera periodically captures an image frame and sends it to the backend server via an HTTP POST request.

- (II)

Data validation: the API verifies the request parameters and stores the received image in the temporary data repository.

- (III)

Detection request: the backend triggers the YOLOv8 detection module through an internal API call, passing the image reference and metadata.

- (IV)

Analysis and classification: the detection module performs object detection (helmet absence/fall event) and returns a JSON response containing bounding box coordinates, class labels, and confidence scores.

- (V)

Incident registration: if a safety violation is detected, the API automatically records the event in the incident database with time, camera ID, and event type.

- (VI)

Alert notification: the system updates the web-based interface through a WebSocket channel, displaying the new event and enabling user acknowledgment.

Upon receiving a descriptor, the ML model retrieves images from the data warehouse and analyses them in a cloud environment. The model has been pre-trained on datasets containing patterns of dangerous behaviour (e.g., lack of a safety helmet). During the analysis, it compares new images with learned representations to identify undesirable situations.

Once a dangerous event has been identified, the developed programme flags the incident in the database, passing the appropriate status (e.g., “HasAlert”) via a POST request handled by the backend server. If they occur, a notification is generated on the panel, enabling immediate response by personnel. Automation of this process reduces the response time to potential incidents.

It is worth noting that the system also allows the collected data to be used to further improve the ML model, increasing its adaptability to the specific conditions of a given work environment. New cases can be used as additional training material, which has a positive impact on the accuracy of detection in the future.

The designed system uses two object detection models from the YOLO family:

YOLO (keremberke/yolov8s-hard-hat-detection)—enabling the detection of the presence of safety helmets and their colour.

YOLO (yolov8s.pt)—used to locate human silhouettes, which, in combination with geometric analysis, enables the identification of falls.

A detailed block diagram of the detection algorithm is shown in

Figure 3.

The video stream from the camera is analysed asynchronously. Every three seconds, the system extracts a single frame, which is then processed by the inference model using the hardhat_processing () and falling_detecting () functions.

The hardhat_processing () function identifies the presence of a safety helmet on the worker’s head. To do this, the image is subjected to object detection using the YOLO model. If a helmet is detected, its colour is analysed in the HSV space. If no helmet is detected, a “NO HARDHAT DETECTION” warning is generated. The algorithm allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple figures within the camera’s field of view.

The falling_detecting () function focuses on detecting human falls. The width-to-height ratio threshold (width ≥ 2× height) used to identify potential human falls was determined empirically during preliminary tests as a simplified heuristic for detecting horizontal body postures, aimed at ensuring computational efficiency in the prototype implementation. In the first stage, all persons in the image are identified, and then the ratio of the width to the height of the area reserved for each of them is analysed. A heuristic has been adopted whereby if the width of the area is at least twice its height, this is interpreted as a lying position, potentially indicating a fall. This approach reduces the number of false alarms, e.g., those resulting from a kneeling position.

The system-level novelty lies in combining two independent YOLOv8-based modules with a low-overhead asynchronous inference loop, an incident-logging backend, and a real-time alerting interface, which collectively support deployment on ordinary edge devices. This distinguishes the present work from prior YOLOv8 studies focused exclusively on algorithmic accuracy without addressing deployment constraints, modularity, or interoperability.

3.3. System Efficiency

After developing the system, the key stage was its validation. For this purpose, a database was developed consisting of photos of people wearing protective helmets and people without protective helmets, as well as falls. The database included 100 photos, which were analysed individually. The dataset used in this study was collected in situ by the authors during controlled observation sessions conducted on an active construction site. All image data were gathered directly by the research team and manually annotated to identify the presence or absence of safety helmets and human falls.

The proprietary dataset used for model training and validation consisted of 200 RGB images (100 for helmet detection and 100 for fall detection) captured on an active construction site under varying lighting and weather conditions. The images were captured on an active construction site under varying lighting and weather conditions using a USB camera connected to a Raspberry Pi 3B+ microcomputer, which streamed 1080p video to the storage server. The camera used for data acquisition was a Razer Kiyo Full HD webcam. All images were manually annotated using the open-source LabelImg 1.8.6. tool, and labels were saved in YOLO format (.txt files containing class ID and bounding box coordinates). The labelling process distinguished two main classes: person_with_helmet/person_without_helmet and person_falling. Given the exploratory scope of this study, the present experiments were conducted on the baseline dataset. In subsequent phases, we plan to extend the dataset and adopt a systematic augmentation pipeline (e.g., horizontal/vertical flips, small-angle rotations, photometric adjustments, and controlled noise injection) together with stratified train/validation/test protocols to preserve class balance. This staged approach is intended to improve generalisation and robustness of the YOLOv8s model while maintaining methodological transparency to support reproducibility.

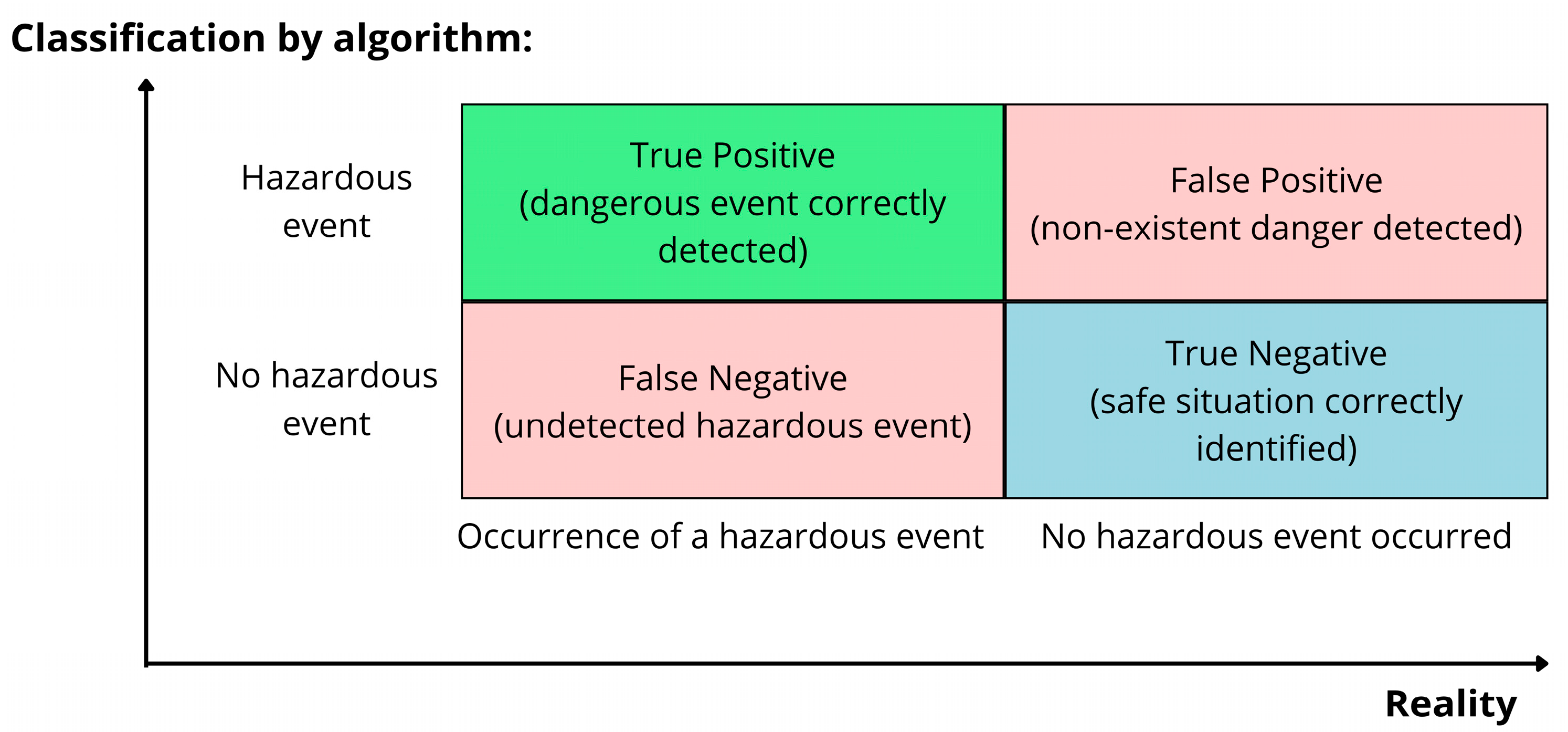

The significance of the classifiers in the analysed test is shown in

Figure 4. The high number of true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) results indicates the high effectiveness of the model. On the other hand, the significant number of false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) results indicates the need for further optimisation of the model.

The quality measures used are summarised in

Table 6.

5. Discussion

The evaluation showed that the developed hazard detection system on construction sites has varying effectiveness depending on the type of event analysed. In the safety helmet detection module (NHD), the system achieved high precision (0.93), which indicates a low level of false positives, and moderate sensitivity (0.68), indicating that some violations were missed. The F1-score (0.79) confirms that the model is well-balanced and effective in recognising irregularities related to the non-use of personal protective equipment. These effectiveness indicators directly address RQ1, confirming that the YOLOv8-based prototype achieves competitive precision and balanced performance for helmet-absence detection under the tested conditions. Similar relationships were observed in studies by Xing et al. [

45] and Feng et al. [

46], where high precision values also co-occurred with slightly lower sensitivity, especially in complex lighting conditions and with varying visibility of protective helmets.

The oblique-view and low-light sensitivities observed here translate into actionable controls: (i) prioritise camera placement with reduced obliqueness and stable heights to preserve discriminative body geometry; (ii) ensure illumination provisioning (task lighting or exposure control) at high-risk zones; and (iii) for fall detection, consider multi-camera overlap or short-clip analysis to recover temporal cues and suppress angle-specific misses. These measures are consistent with prior evidence [

27] on construction-site vision systems and can be implemented without high-end hardware.

In the fall detection module (FD), the system demonstrated very high precision (1.00), which means a complete absence of false alarms. However, the relatively low sensitivity (0.45) indicates that a significant proportion of actual events were not detected correctly. The overall classification accuracy for this category was 0.62, which is partly due to the limited size of the test dataset (

n = 100). This phenomenon is consistent with the observations reported in Alam et al. [

63], where the authors pointed out the low representation of rare classes (e.g., falls) as an important factor leading to the instability of recall metrics and potential overestimation of model performance. Taken together, the high precision but modest recall observed for falls constitutes a qualified answer to RQ1: the prototype avoids false alarms but misses a portion of true fall events, mainly due to data scarcity and viewpoint sensitivity. Although newer YOLO variants are emerging, YOLOv8 remains the most widely validated architecture with publicly replicable baselines in OHS-related tasks. More importantly, the novelty of this work is system-oriented: the method demonstrates how a lightweight YOLOv8 module can be embedded in an integrated safety pipeline under real deployment constraints. The detection stage thus serves not as a stand-alone contribution but as the enabling component of a full supervisory workflow.

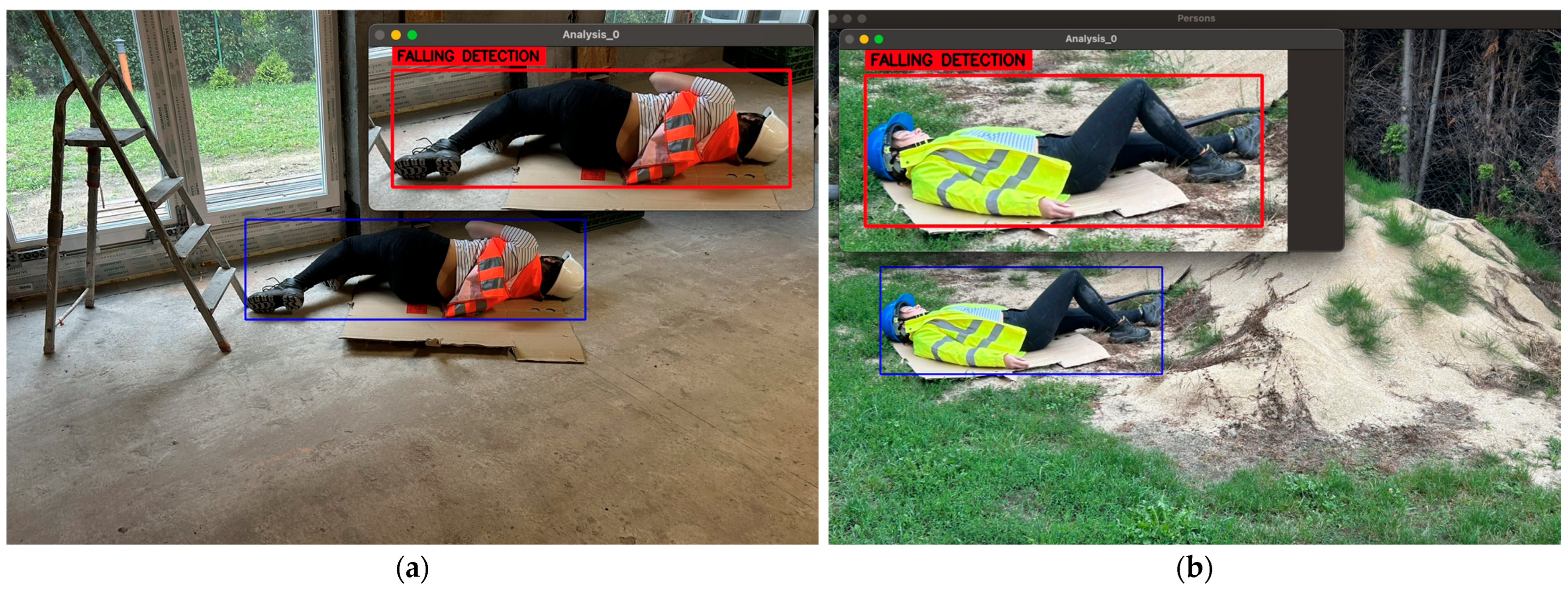

In relation to RQ3, the heuristic assumption used in the system, according to which a fall is identified when the proportions of the bounding box around the human silhouette satisfy the condition that its width is at least twice its height, has a significant impact on the classification effectiveness. In situations where a falling person is recorded, e.g., from the front, the required proportions may not be met even though the event took place. An example of such a situation is shown in

Figure 7b. In this case, the system did not generate an alert despite the actual fall of a person. This is a significant limitation of the currently used approach, which indicates the need for further development work.

Addressing RQ3, the analysis of single image frames is prone to errors resulting from a limited perspective, obstruction of the human silhouette, or an unusual camera angle. This phenomenon has also been described in other works, e.g., Wang et al. [

42] noted that the uniqueness of human body position classification significantly increases when using multi-camera detection, which enables triangulation and a more complete analysis of posture. Therefore, extending the system with data from multiple image sources could significantly increase its effectiveness in engineering practice.

The identified limitations indicate potential directions for further optimisation. In particular, the use of more advanced spatio-temporal analysis methods, such as video frame sequence analysis or the implementation of recurrent neural architectures (e.g., LSTM, GRU), may enable better representation of posture dynamics and improve fall detection performance [

64]. At the same time, expanding the training dataset, especially with different fall scenarios and camera perspectives, could improve the model’s generalisation ability. These observations collectively answer RQ3, pinpointing camera geometry, temporal context, and class imbalance as the dominant levers for improving both accuracy and system throughput in subsequent iterations.

In summary, the system demonstrates high stability and practical usability in detecting static health and safety violations, such as the failure of construction workers to wear protective helmets. Its limitations in detecting dynamic events such as falls are mainly due to simplified detection assumptions and the limited scope of the test data. Despite these limitations, the high accuracy and operational readiness of the system confirm its implementation potential, especially in the context of real-time monitoring of working conditions on construction sites.

Prior studies [

53,

62,

65] report that attention modules (e.g., CBAM/coordinate attention), small-object detection heads, and low-light enhancement routinely improve recall for PPE and human-posture cues in construction imagery while keeping real-time operation feasible on commodity GPUs. These modifications are orthogonal to our pipeline and can be incrementally adopted in subsequent iterations.

6. Conclusions

Based on the design and research work carried out and the analysis of the functional test results, the following conclusions were drawn:

The developed system enables automatic detection of two key safety hazards on construction sites: failure to wear a safety helmet (NHD) and human falls (FD). For the NHD class, a classification accuracy of 0.88, precision of 0.93, and an F1 score of 0.79 were achieved, which indicates high effectiveness in detecting health and safety violations with a low false alarm rate. The FD class was characterised by full precision (1.00), but with low sensitivity (0.45), which indicates the system’s limited ability to detect all falls and requires further development.

The effectiveness of the system is significantly higher in the case of detecting static violations and clearly recognisable visual features, such as the absence of a safety helmet, than in the case of dynamic and difficult to capture phenomena, such as human falls. The results confirm that the effectiveness of fall detection strongly depends on the camera’s viewing angle and the way the worker’s body position is represented. Limiting the analysis to single image frames and using simplified classification heuristics (based on bounding box proportions) can lead to false negative results. The use of multi-camera systems or integration with more advanced image analysis methods (e.g., time sequence analysis, 3D positions estimation) can significantly improve the effectiveness of dynamic event detection.

Thanks to its modular architecture and open API, the developed solution allows for flexible integration with various IT environments, which facilitates its adaptation to different implementation contexts. Thanks to the use of an API, a web application, and an automatic incident recording mechanism, the system can provide real-time support for health and safety supervision. This operational integration of detection, alerting, and event logging via an open API provides a concise, affirmative answer to RQ2, demonstrating near-real-time support for site supervision within the prototype.

The results of the tests indicate significant implementation potential for the developed solution. In particular, the development of the system with video sequence analysis, the use of data from multiple image sources (e.g., panoramic cameras, drones), and integration with IoT sensors (e.g., employee positioning, overload detection) can significantly increase its functionality, adaptability, and effectiveness in real-world conditions.

From a theoretical standpoint, the conducted research contributes to the advancement of adaptable frameworks for real-time hazard detection based on deep learning and open API integration. The proposed architecture demonstrates how convolutional neural networks can be effectively utilised to identify occupational risks in dynamic and unstructured construction environments. From a practical perspective, the developed system confirms the feasibility of deploying AI-driven monitoring solutions in conditions characterised by limited computational resources and constrained infrastructure. Furthermore, the modular design of the platform provides a foundation for future extensions aimed at improving proactive safety management and reducing accident rates in the construction industry. In contrast to prior YOLOv8-based studies, the proposed solution provides an integrated and deployable pipeline combining detection, alert generation, and persistent event documentation through an open API, forming a system-level contribution that extends beyond algorithmic performance.

Regarding RQ1, the prototype met real-time constraints and achieved competitive effectiveness on helmet-absence while exhibiting conservative (high-precision, lower-recall) behaviour for falls under the tested conditions. Concerning RQ2, the system integrates detection, alerting, and event recording through an open REST API, enabling end-to-end monitoring and traceable incident management. For RQ3, accuracy and performance were chiefly driven by training data balance, camera viewpoint/coverage, illumination variability, and single-frame inference limits, which directly motivate sequence-level modelling and multi-source sensing in future work.

7. Limitations

Despite the results confirming the functionality and usefulness of the developed system in engineering practice, this research has several significant limitations that should be taken into account in the further development of the solution.

Firstly, the use of single image frames as the basis for event classification makes it difficult to detect situations that require consideration of the temporal context, such as a sequence of movements leading to a fall. The lack of video sequence analysis reduces the accuracy of posture interpretation and makes it impossible to distinguish between potentially dangerous and harmless situations. This limitation also motivates a systems-level layer: disaster-chain analysis can prioritise cameras, sensors, and procedural barriers located at high-influence nodes of accident propagation, improving overall risk reduction despite per-event detection constraints [

66].

Second, the limited number of examples of the “fall” class in the training and test sets significantly affects the model’s ability to generalise and leads to reduced detection performance in real-world situations. The uneven distribution of data across classes increases the risk of overfitting and generating unstable performance metrics such as recall or F1-score, a phenomenon widely described in the literature on rare event detection.

Another limitation is the system’s dependence on a stable and fast Internet connection, which is required to transfer data to the cloud environment. Transmission disruptions can lead to delays in incident detection and recording, which in critical situations can reduce the effectiveness of the response of construction supervision services. The system has limited resistance to environmental disturbances, in particular changing lighting conditions and dynamic backgrounds (e.g., machines, moving elements of the environment), which may affect the quality of object detection. The developed detection model does not take into account adaptive or compensatory mechanisms that would allow automatic adjustment of analysis parameters to external conditions.