The Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- While existing literature focuses on ESG’s impact on investment efficiency and financial performance, this research specifically examines its effect on environmental performance, clarifying the theoretical relationship between disclosure quality and environmental outcomes.

- 2.

- The paper examines the mechanisms through three specific channels: green innovation, media attention, and executive compensation, providing empirical evidence on how ESG disclosure enhances environmental performance.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Direct Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Environmental Performance

2.2. The Mediating Mechanisms

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Definitions

3.2.1. Explained Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Empirical Model

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Main Results

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Multivariate Regression Analysis

4.2. Robustness

4.2.1. Replacing Key Variables

4.2.2. Excluding Extraordinary Years

4.2.3. Firm Fixed Effects

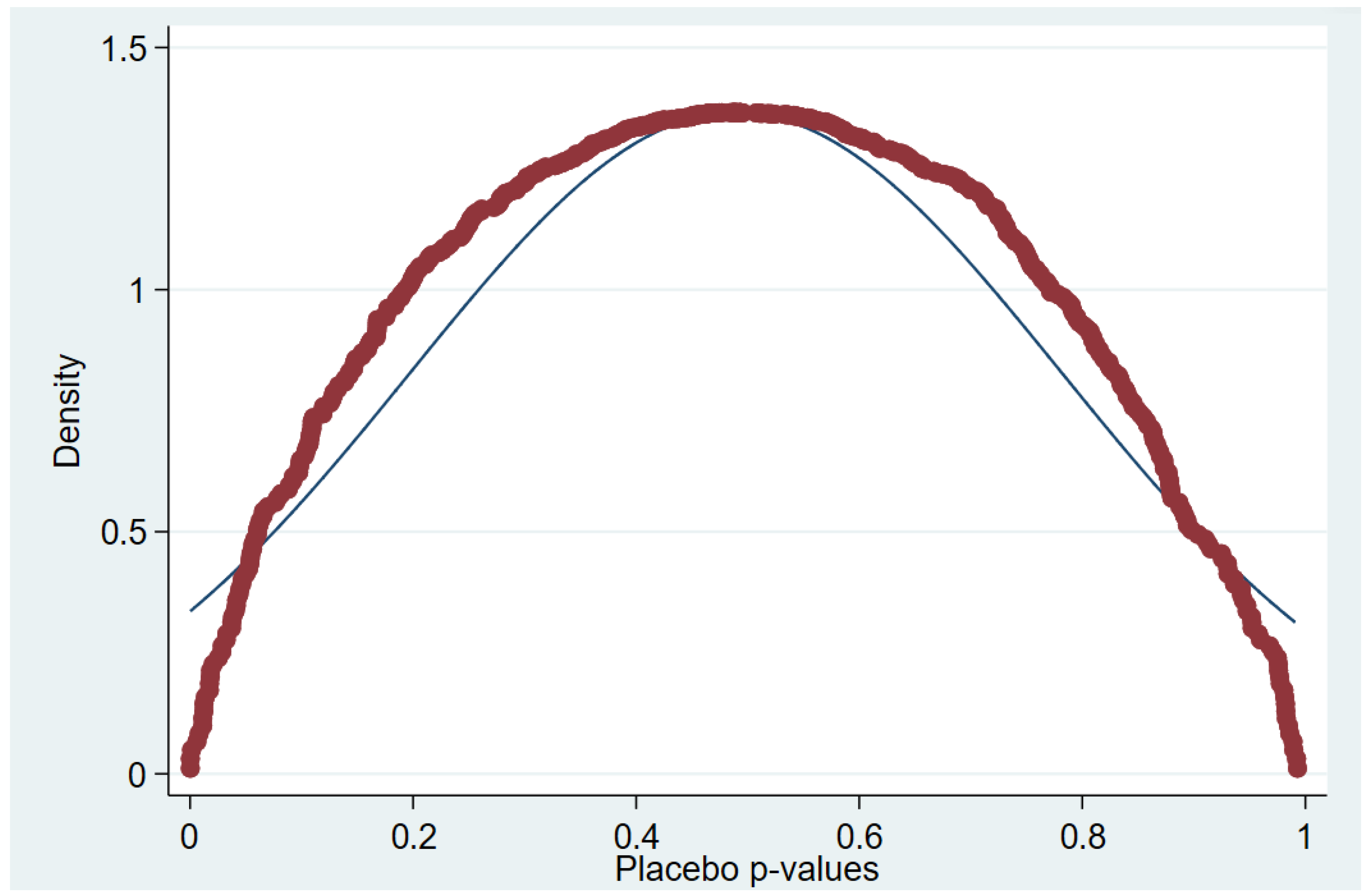

4.2.4. Placebo Test

4.2.5. Endogeneity Tests

4.3. Mechanism Test

4.3.1. Mediation Effect Test Based on Green Innovation

4.3.2. Mediation Effect Test Based on Media Attention

4.3.3. Mediation Effect Test Based on Executive Compensation

4.3.4. Bootstrap Robustness Test

4.4. Further Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity Test Based on Ownership Nature

4.4.2. Heterogeneity Test Based on Internal Control Quality

4.4.3. Heterogeneity Test Based on Industry Environmental Sensitivity

4.4.4. Heterogeneity Test Based on Time

4.5. The Moderating Role of Financial Constraints

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qu, Y. The impact of digital inclusive finance on corporate environmental performance. Stat. Decis. 2023, 39, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Khamisu, M.S.; Paluri, R.A. Emerging trends of environmental social and governance (ESG) disclosure research. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 7, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, C. Peer effects in corporate ESG information disclosure and high-quality development: Based on the perspective of competition and information mechanisms. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2025, 1, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Xu, X. The impact of environmental protection investment on type II agency costs: Also on the moderating effect of internal control. J. Nanjing Audit Univ. 2024, 21, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Hu, D. Corporate ESG performance and innovation: Evidence from A-share listed companies in China. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Eduard, D.; Javier, A. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores and Financial Performance of Multilatinas: Moderating Effects of Geographic International Diversification and Financial Slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.E.P.; Van Luu, B. International Variations in ESG Disclosure—Do Cross-Listed Companies Care More? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 75, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. “Greenwashing” and anti-“Greenwashing” in ESG reports. Finance Account. Mon. 2022, 1, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T. The pollutant discharge permit system and corporate ESG greenwashing. Macroecon. Res. 2025, 1, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y. Industry peer effects in ESG information disclosure of Chinese enterprises: Active response or passive follow-up? South China Financ. 2024, 46, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, C. Corporate strategic greenwashing under ESG disclosure uncertainty: Financing incentives and nonlinear effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Ping, Z.; Xi, Z. The Collaborative Innovation Effect of ESG Signals: Integrating Signaling and Trust Theories. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2025, 21, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. The corporate law response to data governance. Law Rev. 2025, 43, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y. A Study of the Impact Mechanism of Corporate ESG Performance on Surplus Persistence. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, L. Research on the environmental benefits of corporate ESG fulfillment: Analysis based on the perspective of resource acquisition and allocation. Financ. Theory Pract. 2025, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi, E.; Burchi, A.; Goodell, J.W.; Paltrinieri, A. Stakeholders and regulatory pressure on ESG disclosure. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 103, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, T. Does ESG Information Disclosure Improve Green Innovation in Manufacturing Enterprises? Sustainability 2025, 17, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J. Digital transformation and corporate environmental performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 76, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Dong, S. Political connections and environmental performance of private enterprises under the “dual carbon” goals: The mediating effect based on green innovation. Commun. Financ. Account. 2024, 46, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Li, R.; Xue, S.; Zhang, X. Mandatory versus voluntary: The real effect of ESG disclosures on corporate earnings management. J. Int. Money Financ. 2025, 154, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. ESG information disclosure and corporate total factor productivity. Stat. Inf. Forum 2024, 39, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Jiang, Z. ESG performance and corporate markup ratio: Empirical research based on A-share manufacturing listed companies. Financ. Trade Res. 2025, 36, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, R.; Lin, H.; Yu, M.; Ji, L.; Han, M. Media Pressure and Corporate Green Innovation: The Roles of Munificence, Dynamism, and Complexity. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Dou, Y.; Zhang, L. Can CEO’s green experience improve corporate environmental performance? Ecol. Econ. 2024, 40, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liang, Q.; Liu, H. The impact of dual motivations for ESG information disclosure on corporate green innovation performance: The mediating role of green image and the moderating role of value perception. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 42, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Z. The impact of ESG performance on corporate green innovation performance: Considering the mediating role of executive incentives. China Bus. Trade 2025, 34, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Rong, C.; Liu, Y. The impact of compensation incentives on the quality of corporate environmental information disclosure: Analysis based on the moderating and threshold effects of environmental regulation. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Bi, L.; Cen, J.; Wei, Y.; Tuo, Z.; Li, H. Research on the impact of board characteristics on environmental performance. China Mark. 2024, 14, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, W. Executive academic experience and corporate environmental performance. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Niu, J. Corporate governance efficiency, environmental regulation and the quality of ESG information disclosure. Commun. Financ. Account. 2025, 11, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Li, X. Research on the influence mechanism of digital economy spatial correlation network on pollution reduction and carbon mitigation. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 25, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xiao, H.; Ma, Y. Research on the impact of digital-real industrial technology integration on corporate cash flow risk: Empirical evidence from A-share listed companies. Financ. Theory Pract. 2024, 46, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, J.; Hu, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, N. Research on the impact mechanism of corporate ESG performance on new quality productivity: An empirical analysis based on resource-based theory. Sci. Decis. Mak. 2025, 32, 104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, X. Enabling or disabling: ESG performance and corporate labor investment efficiency. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2024, 46, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Lin, Z. Does the volatility of corporate ESG performance affect audit fees? Financ. Account. Mon. 2025, 46, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z. Can CEO Education Promote Environmental Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, X. External tariff shocks, entrepreneurial attention allocation, and innovation development. J. World Econ. 2024, 47, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, D.; Xu, K. Research on the impact of carbon information disclosure on corporate green competitiveness: An empirical analysis based on A-share listed companies in heavily polluting manufacturing industries. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 41, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y. “Integration of Informatization and Industrialization” policy and corporate ESG performance: A quasi-natural experiment based on the integration. Financ. Theory Pract. 2025, 47, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Cui, W. Research on the mechanism of ESG promoting corporate performance: From the perspective of corporate innovation. Sci. Sci. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Liu, Y. The impact of patient capital on the high-quality development of “Zhuanjingtexin” enterprises. Enterp. Econ. 2025, 44, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Testing methods for moderated mediation models: Competition or substitution? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Performance | EP | For details, refer to variable definition |

| ESG Information Disclosure | ESG | Hua Zheng ESG Rating |

| Green Innovation | RD | R&D expenditure/Total assets |

| Media Attention | Media | Natural logarithm of the total number of online media reports |

| Executive Compensation | Salary | Natural logarithm of the total compensation of the top three executives |

| Firm Size | SIZE | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Firm Age | AGE | Natural logarithm of (Year of observation − Year of establishment + 1) |

| Profitability | ROA | Net profit/Total assets |

| Leverage | LEV | Total liabilities/Total assets |

| Largest Shareholder Ownership | TOP1 | Percentage of shares held by the largest shareholder |

| CEO Duality | DUAL | Equals 1 if the chairman and general manager are the same person, otherwise 0 |

| Board Size | BOARD | Natural logarithm of (Number of board members + 1) |

| Proportion of Independent Directors | INDBOARD | Number of independent directors/Total number of board members |

| Big Four Auditing | AUDIT | Equals 1 if the auditor is one of the Big Four international firms, otherwise 0 |

| Management Shareholding Ratio | MHOLD | Total shares held by directors, supervisors, and senior executives/Total shares outstanding |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Industry | Industry dummy variables |

| Year Effects | Year | Year dummy variables |

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | 31,630 | 4.121 | 2.198 | 0.000 | 9.000 | 1.000 |

| EP1 | 1694 | 0.658 | 0.077 | 0.414 | 0.669 | 0.819 |

| ESG | 31,630 | 2.206 | 0.993 | 1.000 | 8.000 | 4.000 |

| SIZE | 31,630 | 22.177 | 1.243 | 20.070 | 26.152 | 21.972 |

| LEV | 31,630 | 0.396 | 0.199 | 0.051 | 0.884 | 0.384 |

| ROA | 31,630 | 0.039 | 0.061 | −0.229 | 0.201 | 0.040 |

| TOP1 | 31,630 | 33.326 | 14.441 | 8.350 | 72.800 | 31.070 |

| DUAL | 31,630 | 0.328 | 0.469 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| INDBOARD | 31,630 | 0.377 | 0.052 | 0.333 | 0.571 | 0.364 |

| AGE | 31,630 | 2.947 | 0.320 | 2.079 | 3.611 | 2.996 |

| MHOLD | 31,630 | 0.165 | 0.205 | 0.000 | 0.693 | 0.044 |

| BOARD | 31,630 | 2.109 | 0.194 | 1.609 | 2.639 | 2.197 |

| AUDIT | 31,630 | 0.055 | 0.228 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| EP Basic | EP Full Model | |

| ESG | 0.547 *** | 0.445 *** |

| (25.987) | (25.848) | |

| SIZE | 0.508 *** | |

| (22.598) | ||

| LEV | 0.282 ** | |

| (2.360) | ||

| ROA | 1.039 *** | |

| (4.194) | ||

| TOP1 | 0.004 *** | |

| (2.614) | ||

| DUAL | −0.129 *** | |

| (−3.474) | ||

| INDBOARD | −0.468 | |

| (−1.112) | ||

| AGE | 0.130 * | |

| (1.833) | ||

| MHOLD | −0.547 *** | |

| (−5.351) | ||

| BOARD | 0.478 *** | |

| (3.877) | ||

| AUDIT | 0.466 *** | |

| (4.714) | ||

| Constant | −0.180 ** | −12.387 *** |

| (−2.133) | (−21.386) | |

| Controls | No | Yes |

| Industry FEs | No | Yes |

| Year FEs | No | Yes |

| Observations | 31,630 | 31,630 |

| R2 | 0.061 | 0.382 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | EP1 | EP | EP | |

| EP Alternative ESG Measure | Alternative EP Measure | Excluding Pandemic Years | Firm & Year FEs | |

| ESG1 | 0.129 *** | |||

| (23.178) | ||||

| ESG | 0.007 ** | 0.476 *** | 0.167 *** | |

| (2.264) | (25.189) | (12.296) | ||

| Constant | −7.184 *** | 0.573 *** | −12.580 *** | −7.056 *** |

| (−6.114) | (5.927) | (−20.918) | (−5.823) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FEs | No | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 9391 | 1694 | 24,920 | 31,630 |

| R2 | 0.412 | 0.276 | 0.394 | 0.702 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | ESG | EP | ESG | EP | |

| PSM Sample | First Stage | Second Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | |

| ESG | 0.466 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.668 *** | ||

| (22.025) | (3.058) | (21.49) | |||

| IVESG | 0.969 *** | ||||

| (36.736) | |||||

| IVESG1 | 0.572 *** | ||||

| (99.88) | |||||

| Constant | −12.360 *** | −5.837 *** | −1.347 *** | ||

| (−17.304) | (−19.522) | (−8.93) | |||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F | 1349.511 | 9976.496 | |||

| [16.38] | [16.38] | ||||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM | 625.462 *** | 1199.855 *** | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 15,173 | 31,630 | 31,630 | 26,388 | 26,388 |

| R2 | 0.381 | 0.221 | 0.192 | 0.456 | 0.204 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | RD | EP | Media | EP | Salary | EP | |

| ESG | 0.445 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.441 *** | 0.014 * | 0.444 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.440 *** |

| (25.848) | (7.833) | (25.628) | (1.888) | (25.796) | (5.799) | (25.680) | |

| RD | 2.629 *** | ||||||

| (2.719) | |||||||

| Media | 0.101 *** | ||||||

| (4.609) | |||||||

| Salary | 0.146 *** | ||||||

| (4.319) | |||||||

| Constant | −12.387 *** | 0.056 *** | −12.533 *** | −2.591 *** | −12.125 *** | 9.215 *** | −13.729 *** |

| (−21.386) | (8.495) | (−21.608) | (−9.267) | (−21.018) | (44.319) | (−20.786) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 31,630 | 31,630 | 31,630 | 31,630 | 31,630 | 31,630 | 31,630 |

| R2 | 0.385 | 0.376 | 0.386 | 0.423 | 0.386 | 0.439 | 0.386 |

| Green Innovation | Media Attention | Executive Compensation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| bs_1 | 0.0037 *** | 0.0014 ** | 0.0049 *** |

| [0.0022, 0.0053] | [0.0004, 0.0024] | [0.0033, 0.0064] | |

| bs_2 | 0.4412 *** | 0.4435 *** | 0.4401 *** |

| [0.4200, 0.4624] | [0.4228, 0.4643] | [0.4184, 0.4617] | |

| bs_3 | 0.4449 *** | 0.4449 *** | 0.4449 *** |

| [0.4238, 0.4661] | [0.4241, 0.4658] | [0.4233, 0.4666] | |

| Observations | 31,630 | ||

| Ownership | Internal Control | Industry Env. Sensitivity | Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) EP SOEs |

(2) EP Non-SOEs |

(3) EP High |

(4) EP Low |

(5) EP High |

(6) EP Low |

(7) EP 2018–2023 |

(8) EP 2011–2017 | |

| ESG | 0.535 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.539 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.513 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.467 *** | 0.419 *** |

| (16.27) | (20.34) | (23.19) | (19.21) | (14.51) | (21.84) | (24.34) | (16.18) | |

| Constant | −11.164 *** | −11.448 *** | −13.162 *** | −11.319 *** | −11.435 *** | −12.701 *** | 13.014 *** | 11.128 *** |

| (−9.81) | (−17.19) | (−18.76) | (−15.76) | (−9.34) | (−19.77) | (−20.24) | (−13.54) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Group diff. p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.024 | ||||

| Observations | 8918 | 22,712 | 14,717 | 14,718 | 9420 | 22,210 | 19,885 | 11,745 |

| R2 | 0.420 | 0.349 | 0.419 | 0.349 | 0.336 | 0.364 | 0.371 | 0.323 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD | Media | Salary | EP | EP | EP | |

| ESG | 0.001 *** | 0.013 * | 0.033 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.442 *** |

| (7.47) | (1.92) | (5.82) | (25.62) | (25.78) | (25.67) | |

| FC_c | 0.002 | −0.181 | −0.097 | |||

| (0.57) | (−1.62) | (−1.13) | ||||

| ESG × FC | −0.002 *** | −0.114 *** | −0.055 *** | |||

| (−3.99) | (−4.72) | (−3.12) | ||||

| RD | 2.692 *** | |||||

| (2.78) | ||||||

| Media | 0.102 *** | |||||

| (4.63) | ||||||

| Salary | 0.144 *** | |||||

| (4.28) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.089 *** | 0.107 | 10.576 *** | −12.566 *** | −12.150 *** | −13.748 *** |

| (10.39) | (0.29) | (38.11) | (−21.64) | (−21.03) | (−20.81) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 31,242 | 31,242 | 31,242 | 31,242 | 31,242 | 31,242 |

| R2 | 0.374 | 0.428 | 0.436 | 0.382 | 0.383 | 0.383 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, L.; Sun, H.; Chen, L. The Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310583

Wu L, Sun H, Chen L. The Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310583

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Lianghai, Hao Sun, and Liwen Chen. 2025. "The Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310583

APA StyleWu, L., Sun, H., & Chen, L. (2025). The Impact of ESG Information Disclosure on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies. Sustainability, 17(23), 10583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310583