Management Practices and Consumption Patterns of Small Ruminants in the Fiji Islands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

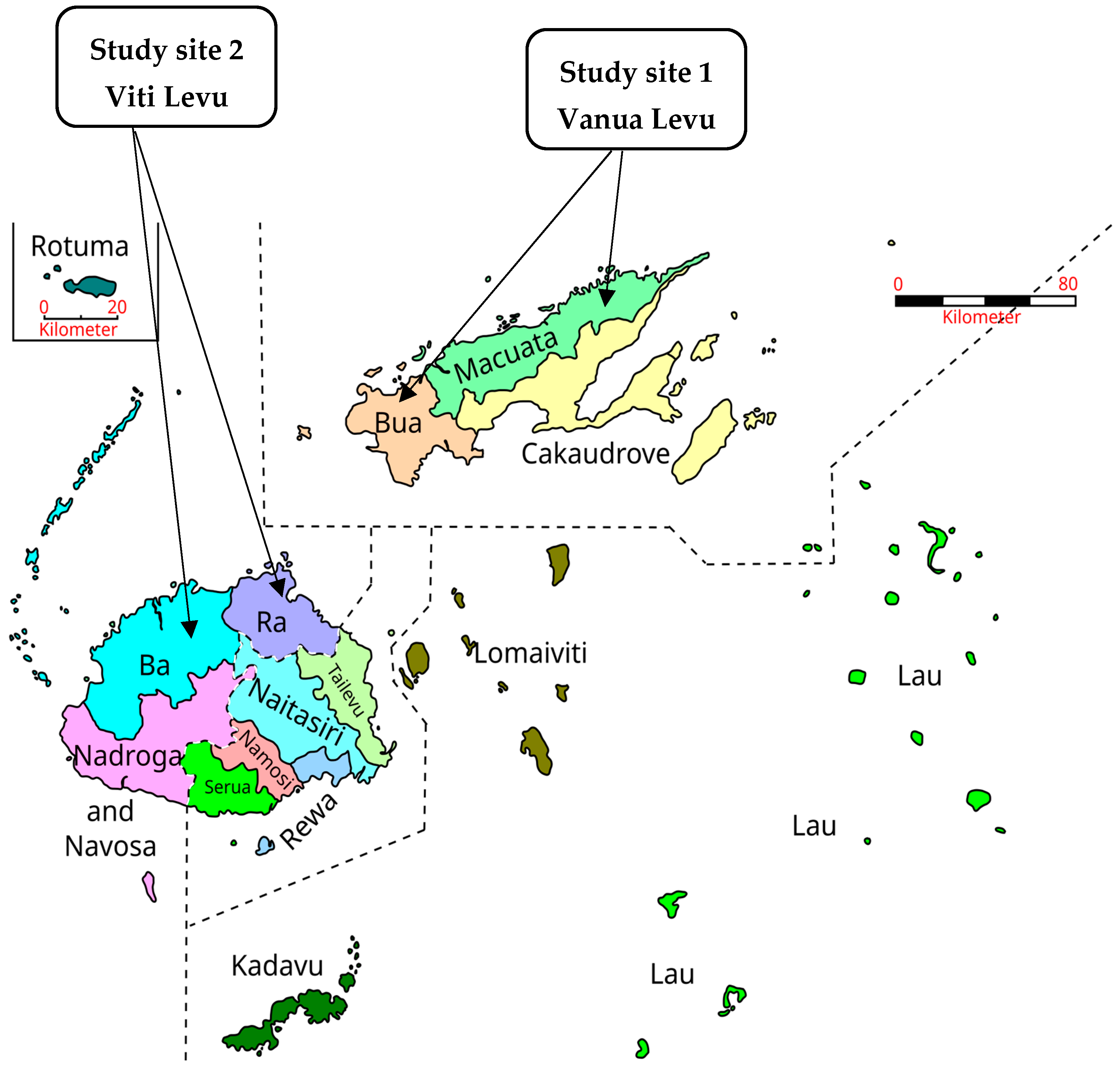

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Sampling Procedure and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Purposes for Keeping Small Ruminants and Challenges Faced

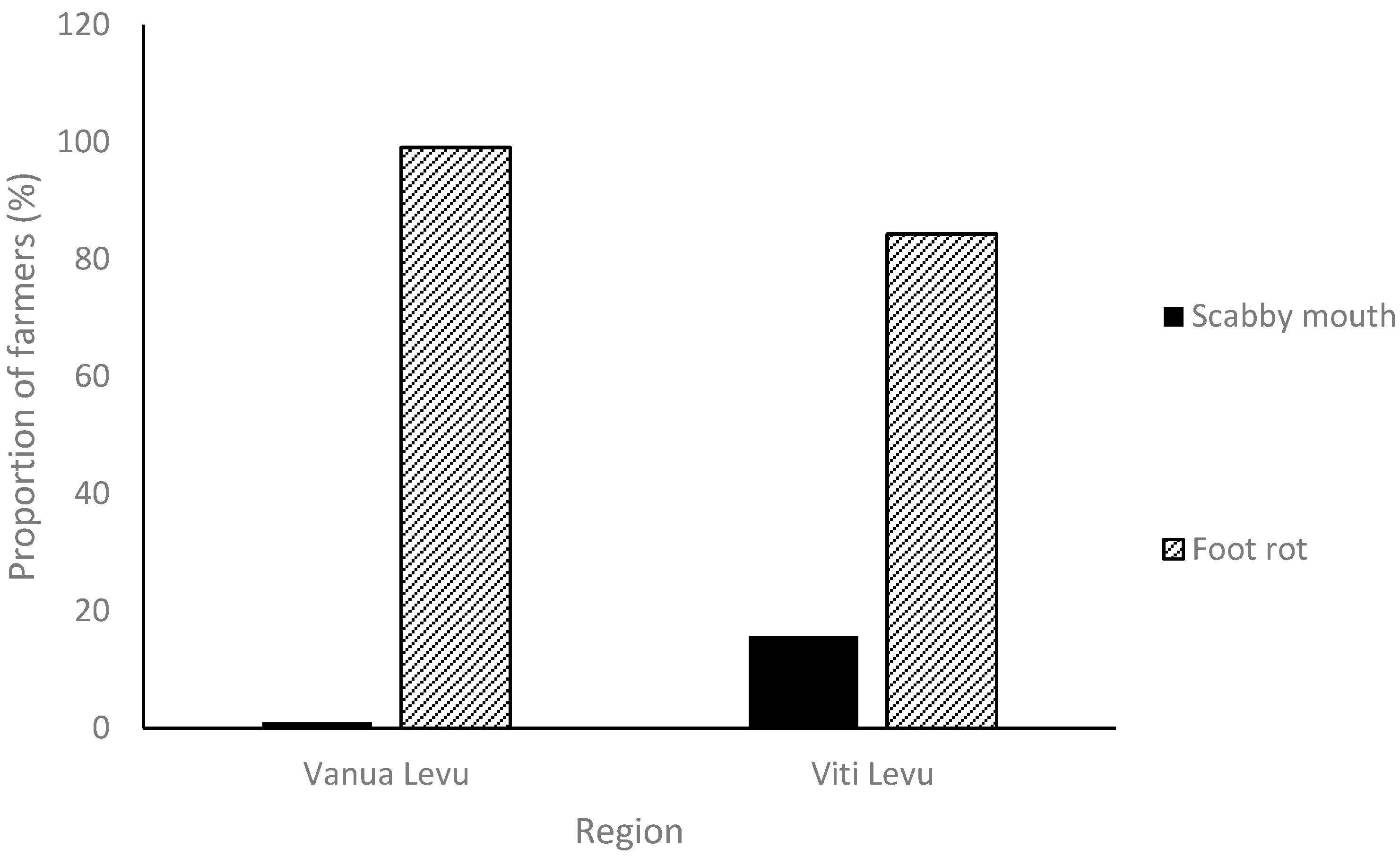

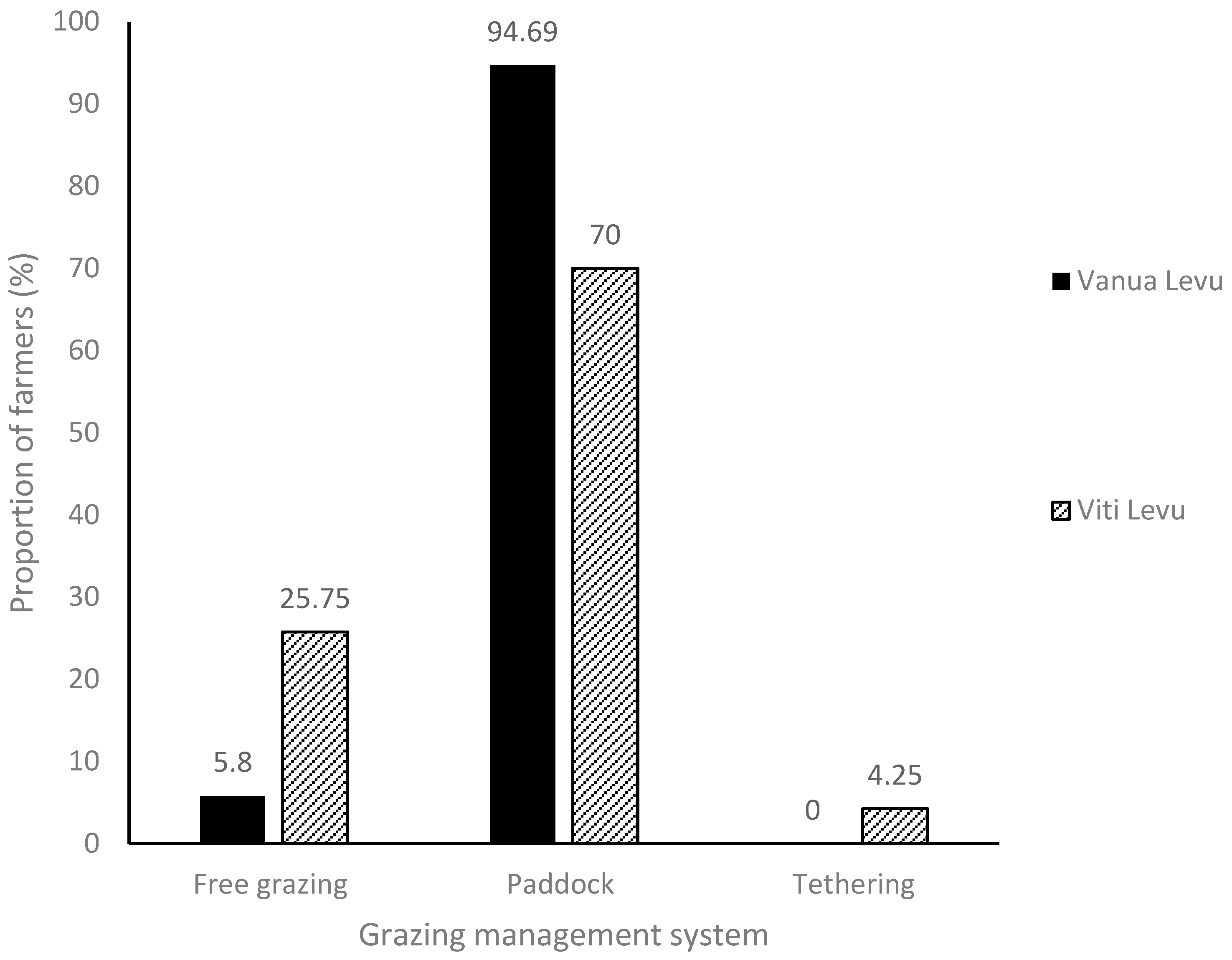

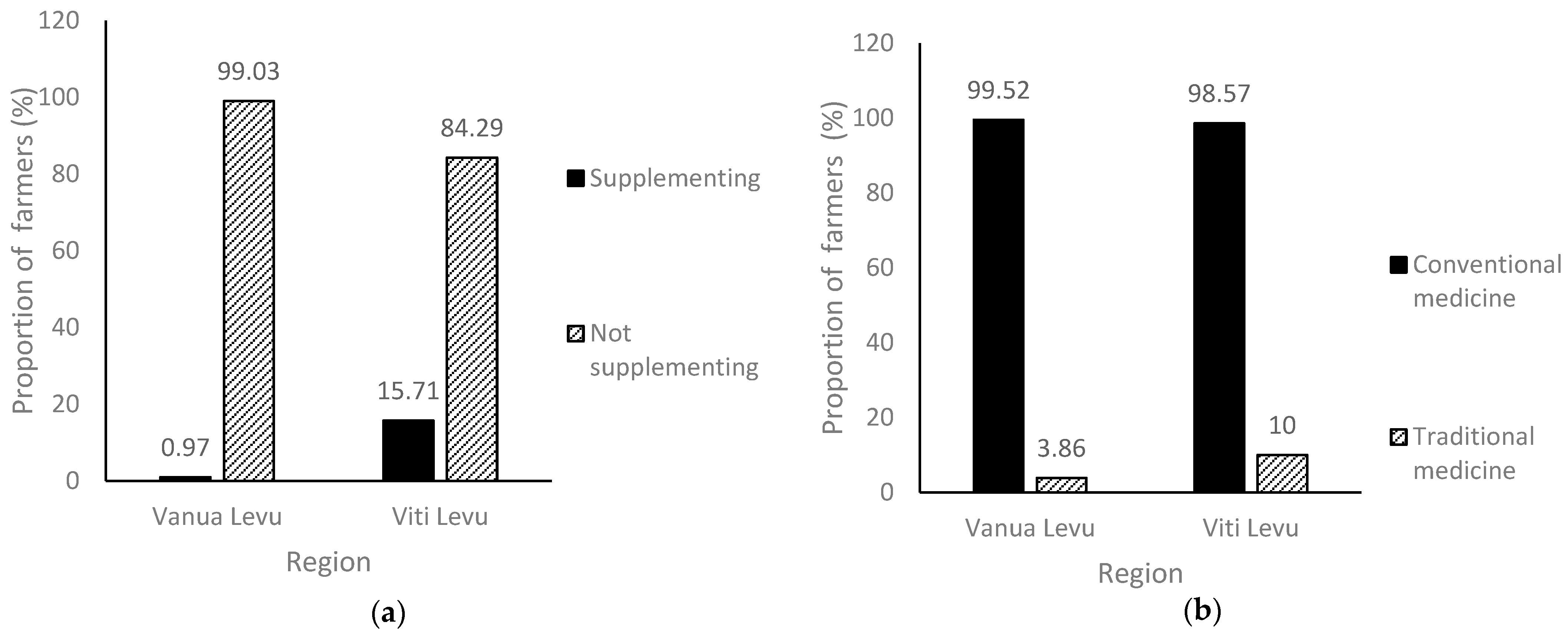

3.3. Small Ruminant Management Practices

3.4. Slaughter and Consumption Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowley, F.; Smith, G.; Roschinsky, R.; Carnegie, M.; Juan, D.; Tabuaciri, P.; Chand, A.; Okello, A. Project Assessment of Markets and Production Constraints to Small Ruminant Farming in the Pacific Island Countries. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/lps-2016-021 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Foraete, H.M. Food Security Strategies for the Republic of Fiji. The ESCAP Repository. 2001. Available online: https://repository.unescap.org/handle/20.500.12870/5914 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Taylor, M.; McGregor, A.; Dawson, B. Vulnerability of Pacific Agriculture and Forestry to Climate Change; Secretariat of the Pacific Community: Noumea, New Caledonia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trudinger, H.; Crimp, S.; Friedman, R.S. Food systems in the face of climate change: Reviewing the state of research in South Pacific Islands. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Moala, A.; McKenzie, B.; Santos, J.A.; Palu, A.; Deo, A.; Lolohea, S.; Sanif, M.; Naivunivuni, P.; Kumar, S.; et al. Food insecurity, COVID-19 and diets in Fiji–A cross-sectional survey of over 500 adults. Glob. Health 2023, 19, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacific Community (SPC). Fiji Livestock Sector Strategy Final Report. 2018. Available online: https://pafpnet.spc.int/attachments/article/535/Fiji%20Livestock%20Sector%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Duncan, R. Setting Agricultural Research Priorities in Fiji (No. eco_2010_06). Research Papers in Economics. 2010. Available online: https://www.econbiz.de/Record/setting-agricultural-research-priorities-in-fiji-duncan-ronald/10008665204 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Balehegn, M.; Duncan, A.; Tolera, A.; Ayantunde, A.A.; Issa, S.; Karimou, M.; Zampaligré, N.; André, K.; Gnanda, I.; Varijakshapanicker, P.; et al. Improving adoption of technologies and interventions for increasing supply of quality livestock feed in low-and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidano, A.; Holt, H.; Durrance-Bagale, A.; Tak, M.; Rudge, J.W. Exploring why animal health practices are (not) adopted among smallholders in low and middle-income countries: A realist framework and scoping review protocol. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 915487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilong, G.P. Smallholder Livestock Development in Papua New Guinea. 1986, pp.119–122. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20210454478 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- FAO. (Ed.) Grazing Livestock in the Southwest Pacific; FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific: Apia, Samoa, 1998; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/w9676e/W9676E00.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Rae, A.N. Changing food consumption patterns in East Asia: Implications of the trend towards livestock products. Agribus. Int. J. 1997, 13, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Rounsevell, M.D.; Dislich, C.; Dodson, J.R.; Engström, K.; Moran, D. Drivers for global agricultural land use change: The nexus of diet, population, yield and bioenergy. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafere, K.; Worku, I. Consumption Patterns of Livestock Products in Ethiopia: Elasticity Estimates Using HICES (2004/05) Data. CGSpace. 2012. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/153861 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Mao, Y.; Hopkins, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X. Consumption patterns and consumer attitudes to beef and sheep meat in China. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2016, 4, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, J. Vegetation ecology of Fiji: Past, present, and future perspectives. Pac. Sci. 1992, 46, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Benefits of crop diversification in Fiji’s sugarcane farming. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2020, 7, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiiba, N.; Singh, P.; Charan, D.; Raj, K.; Stuart, J.; Pratap, A.; Maekawa, M. Climate change and coastal resiliency of Suva, Fiji: A holistic approach for measuring climate risk using the climate and ocean risk vulnerability index (CORVI). Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2023, 28, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeou, N.; Hawksley, C.; Wali, N.; Lountain, S.; Rowe, E.; West, C.; Barratt, L. Food security and small holder farming in Pacific Island countries and territories: A scoping review. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2022, 1, e0000009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Molecular Genetic Characterization of Animal Genetic Resources; FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines: Apia, Samoa, 2011; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Wali, N.; Georgeou, N.; Molimau-Samasoni, S. Indigenous Knowledge, Gender and Agriculture: A Scoping Review of Gendered Roles for Food Sustainability in Tonga, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Fiji. Land 2025, 14, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, F.O. Gender participation in sheep and goat farming in Najran, Southern Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyemo, A.A.; Silas, E. The role of culture in achieving sustainable agriculture in South Africa: Examining zulu cultural views and management practices of livestock and its productivity. In Regional Development in Africa; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Ogolla, K.O.; Chemuliti, J.K.; Ngutu, M.; Kimani, W.W.; Anyona, D.N.; Nyamongo, I.K.; Bukachi, S.A. Women’s empowerment and intra-household gender dynamics and practices around sheep and goat production in South East Kenya. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiono, J.R. Fifty Years of Independence: Indigenous Perception on Sustainable Land Development in Fiji. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Schaub, S.; Wuepper, D.; Finger, R. Culture and agricultural biodiversity conservation. Food Policy 2023, 120, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bhati, J.P. Challenges and opportunities for agrarian transformation and development of agribusinesses in Fiji. Asia-Pacific J. Rural. Dev. 2011, 21, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talore, D.G.; Girma, A.; Azage, T.; Gemeda, B.S. Factors affecting sheep and goat flock dynamics and off-take under resource-poor smallholder management systems, southern Ethiopia. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2018, 8, 2224–3208. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.D.; Nguyen, C.O.; Chau, T.M.L.; Nguyen, D.Q.D.; Han, A.T.; Le, T.T.H. Goat production, supply chains, challenges, and opportunities for development in Vietnam: A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocho, T.; Abebe, G.; Tegegne, A.; Gebremedhin, B. Marketing value-chain of smallholder sheep and goats in crop-livestock mixed farming system of Alaba, Southern Ethiopia. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 96, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, C. Goats—A pathway out of poverty. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 60, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APAARI. Sheep and Goats in Fiji and Papua New Guinea—Success Story; Asia Pacific Association of Agricultural Research Institutions: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021; ISBN 978-81-85992-12-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold, R.; Sonevilay, N.; Masami, T. Backyard farming and slaughtering—Keeping tradition safe. In Food Safety Technical Toolkit for Asia and the Pacific No. 2; FAO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.; Budisatria, I.G.S.; Widayanti, R.; Artama, W.T. The impact of religious festival on roadside livestock traders in urban and peri-urban areas of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Vet. World 2019, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutibvu, T.; Maburutse, B.E.; Mbiriri, D.T.; Kashangura, M.T. Constraints and opportunities for increased livestock production in communal areas: A case study of Simbe, Zimbabwe. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2012, 24, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, K.; Eeswaran, R.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Hernandez-Suarez, J.S. Livestock and aquaculture farming in Bangladesh: Current and future challenges and opportunities. Cogent Food Agric 2023, 9, 2241274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongoma, V.; Rahman, M.A.; Ayugi, B.; Nisha, F.; Galvin, S.; Shilenje, Z.W.; Ogwang, B.A. Variability of diurnal temperature range over Pacific Island countries, a case study of Fiji. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2021, 133, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, B.; Kiunga, P.; Gachohi, J.; Sindato, C.; Mbotha, D.; Robinson, T.; Lindahl, J.; Grace, D. Effects of climate change on the occurrence and distribution of livestock diseases. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 137, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brioudes, A.; Warner, J.; Hedlefs, R.; Gummow, B. A review of domestic animal diseases within the Pacific Islands region. Acta trop. 2014, 132, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naden, K. The prevalence of livestock diseases in the South Pacific. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2191–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukana, A.; Hedlefs, R.; Gummow, B. The impact of national policies on animal disease reporting within selected Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018, 50, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakare, A.G.; Kour, G.; Akter, M.; Iji, P.A. Impact of climate change on sustainable livestock production and existence of wildlife and marine species in the South Pacific island countries: A review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; Shah, S.; Gibson, D. Demystifying agritourism development in Fiji: Inclusive growth for smallholders. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 22, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, E.L.; Grahn, C.; Ljung, I.; Sattorov, N.; Boqvist, S.; Magnusson, U. Prevalence and risk factors for Brucella seropositivity among sheep and goats in a peri-urban region of Tajikistan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loul, S.; Wade, A.; Nlôga, A.M.N. Sero-Prevalence and Risk Factors of Diffusion of Peste des Petits Ruminants in Cameroon. Open J. Vet. Med. 2020, 10, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.B.; Smith, T. Feeding strategies to increase small ruminant production in dry environments. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 77, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yisehak, K.; Janssens, G.P. The impacts of imbalances of feed supply and requirement on productivity of free-ranging tropical livestock units: Links of multiple factors. Afr. J. Appl. Res. 2014, 6, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Liehr, E.; Millar, J.; Walkden-Brown, S.; Chittavong, M.; Olmo, L. Farmer experiences with goat raising in Lao PDR: Implications for improving husbandry and sustaining viable systems. Int. J. Agricult. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2344778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, A.H.B.A. Animal Welfare in Islam, 1st ed.; Kube Publishing Ltd.: Leicestershire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tesema, Z.; Alemayehu, K.; Kebede, D.; Getachew, T.; Deribe, B.; Alebachew, G.W.; Yizengaw, L. Performance evaluation of boer × central highland crossbred bucks and farmers’ perceptions on crossbred goats in northeastern Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022, 6998276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chae, B.J.; Bhuiyan, A.K.F.H.; Sarker, S.C.; Hossain, M.M. Goat production system at Mymensingh district in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 47, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Diarra, S.S.; Silva, T.; Mala, S.; Baleiverata, A.R.; Tiko, A.; Cowley, F. Differences in Feeding Practices and Supplementation on Small Ruminant Farms in Four Provinces of Fiji. USP Repository. 2022. Available online: https://repository.usp.ac.fj/id/eprint/13799/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Islam, M.A.; Islam, A.F. Socio-economic condition of goat farmers and management practices of goats in selected areas of Munshiganj district of Bangladesh. Asian Australas. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2018, 3, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaze, F.R.; Chimonyo, M.; Dzama, K. Variation in the functions of village goats in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewdie, B.; Urge, M.; Tadesse, Y.; Gizaw, S. Factors affecting Arab goat flock dynamics in western lowlands of Ethiopia. Open J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 9, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, N.H.; Webb, E.C. Managing goat production for meat quality. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 89, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocho, T.K. Production and Marketing Systems of Sheep and Goats in Alaba, Southern Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia, April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aepli, M.; Finger, R. Determinants of sheep and goat meat consumption in Switzerland. Agric. Food econ. 2013, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.T. Goat meat production and research in Africa and Latin America. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Goat Conference, New Delhi, India, 2–8 March 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, V.S.S.; Kirton, A.H. Evaluation and classification of live goats and their carcasses and cuts. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Goats, New Delhi, India, 2–8 March 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jemberu, W.T.; Mayberry, D. Farm-level livestock loss and risk factors in Ethiopian livestock production systems. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency (%) | Chi-Square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sub-Components | Vanua Levu | Viti Levu | |

| Gender | ns | |||

| Male | 99.45 | 100 | ||

| Female | 0.55 | 0 | ||

| Age | ns | |||

| <30 years | 3.9 | 1.4 | ||

| >30 years | 96.1 | 98.6 | ||

| Education | ns | |||

| Formal Education | 100 | 90 | ||

| No formal Education | 0 | 10 | ||

| Religion | ns | |||

| Hindus | 94.54 | 88.57 | ||

| Islam | 4.92 | 2.86 | ||

| Christians | 0.55 | 8.57 | ||

| Occupation | ns | |||

| Unemployed | 90.16 | 84.29 | ||

| Employed | 9.84 | 15.71 | ||

| Land size | ns | |||

| <10 acres | 15.5 | 8.6 | ||

| 10–19 acres | 24.8 | 20 | ||

| >20 acres | 59.7 | 71.4 | ||

| Vanua Levu | Viti Levu | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose for keeping small ruminants | ||

| Meat | 2.05 ± 0.02 (2) a | 2.36 ± 0.05 (2) b |

| Hobby | 2.85 ± 0.19 (3) a | 2.86 ± 0.03 (3) a |

| Main income | 1.01 ± 0.004 (1) a | 1.00 ± 0.01 (1) a |

| Ceremonies | 3.98 ± 0.017 (4) a | 3.97 ± 0.03 (4) a |

| Challenges faced | ||

| Theft | 3.69 ± 0.076 (4) a | 3.04 ± 0.12 (4) b |

| Predation | 2.82 ± 0.04 (3) a | 2.62 ± 0.06 (3) b |

| Diseases | 1.38 ± 0.072 (1) a | 1.96 ± 0.12 (1) b |

| Cyclones | 2.12 ± 0.03 (2) a | 2.37 ± 0.3 (2) b |

| Predictors | Paddock | Free Grazing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds | LCI | UCI | Odds | LCI | UCI | |

| Location (Vanua Levu vs. Viti Levu) | ||||||

| Religion (Hindus vs. Muslims) | 3.61 * | 1.78 | 7.48 | 0.351 * | 0.169 | 0.731 |

| Age (Young vs. old) | 1.42 NS | 0.452 | 4.447 | 1.059 NS | 0.368 | 3.046 |

| Education (not educated vs. educated) | 2.543 NS | 0.729 | 8.873 | 0.397 NS | 0.114 | 1.382 |

| Size (small vs. large) | 0.571 NS | 0.273 | 1.194 | 2.055 NS | 0.964 | 4.382 |

| Occupation (not working vs. working) | 0.142 NS | 0.018 | 1.133 | 6.816 NS | 0.848 | 54.769 |

| Vanua Levu | Viti Levu | |

|---|---|---|

| Source of small ruminant | ||

| Own flock | 1.00 ± 0.006 a (1) | 1.05 ± 0.008 a (1) |

| Buy from neighbors | 2.60 ± 0.038 a (3) | 2.10 ± 0.052 b (2) |

| Buy from other villagers | 2.39 ± 0.038 a (2) | 2.90 ± 0.052 b (3) |

| Gift | 3.99 ± 0.006 a (4) | 4.00 ± 0.008 a (4) |

| Age at slaughter | ||

| Less than a year | 1.77 ± 0.0324 a (1) | 1.92 ± 0.0442 b (2) |

| A year and a half | 1.22 ± 0.032 a (2) | 1.07 ± 0.044 b (1) |

| Older than 2 years | 2.99 ± 0.006 a (3) | 2.90 ± 0.052 a (3) |

| Vanua Levu | Viti Levu | |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred meat cuts | ||

| Ribs | 4.73 ± 0.073 (5) | 4.70 ± 0.0998 (5) |

| Shoulder | 3.10 ± 0.028 (3) | 3.10 ± 0.0382 (3) |

| Neck | 4.10 ± 0.044 (4) | 4.20 ± 0.061 (4) |

| Shank | 1.16 ± 0.046 (1) | 1.20 ± 0.064 (1) |

| Loin | 6.05 ± 0.022 (6) | 6.10 ± 0.030 (6) |

| Brisket | 1.91 ± 0.053 (2) | 1.90 ± 0.073 (2) |

| Offal | 6.56 ± 0.104 (7) | 6.80 ± 0.142 (7) |

| Reasons for preference | ||

| Tender and juicy | 3.00± 0.009 a (3) | 3.00 ± 0.011 a (3) |

| Taste | 2.00 ± 0.118 a (2) | 2.42 ± 0.169 b (2) |

| Fat content | 5.00 ± 0.037 a (5) | 4.68 ± 0.051 b (5) |

| Habituated | 1.00± 0.039 a (1) | 1.31± 0.051 b (1) |

| Affordability | 3.99± 0.020 a (4) | 3.82 ± 0.028 b (4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swarath, P.P.; Bakare, A.G.; Iji, P.A.; Zindove, T.J. Management Practices and Consumption Patterns of Small Ruminants in the Fiji Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310497

Swarath PP, Bakare AG, Iji PA, Zindove TJ. Management Practices and Consumption Patterns of Small Ruminants in the Fiji Islands. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310497

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwarath, Prethy P., Archibold G. Bakare, Paul A. Iji, and Titus J. Zindove. 2025. "Management Practices and Consumption Patterns of Small Ruminants in the Fiji Islands" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310497

APA StyleSwarath, P. P., Bakare, A. G., Iji, P. A., & Zindove, T. J. (2025). Management Practices and Consumption Patterns of Small Ruminants in the Fiji Islands. Sustainability, 17(23), 10497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310497