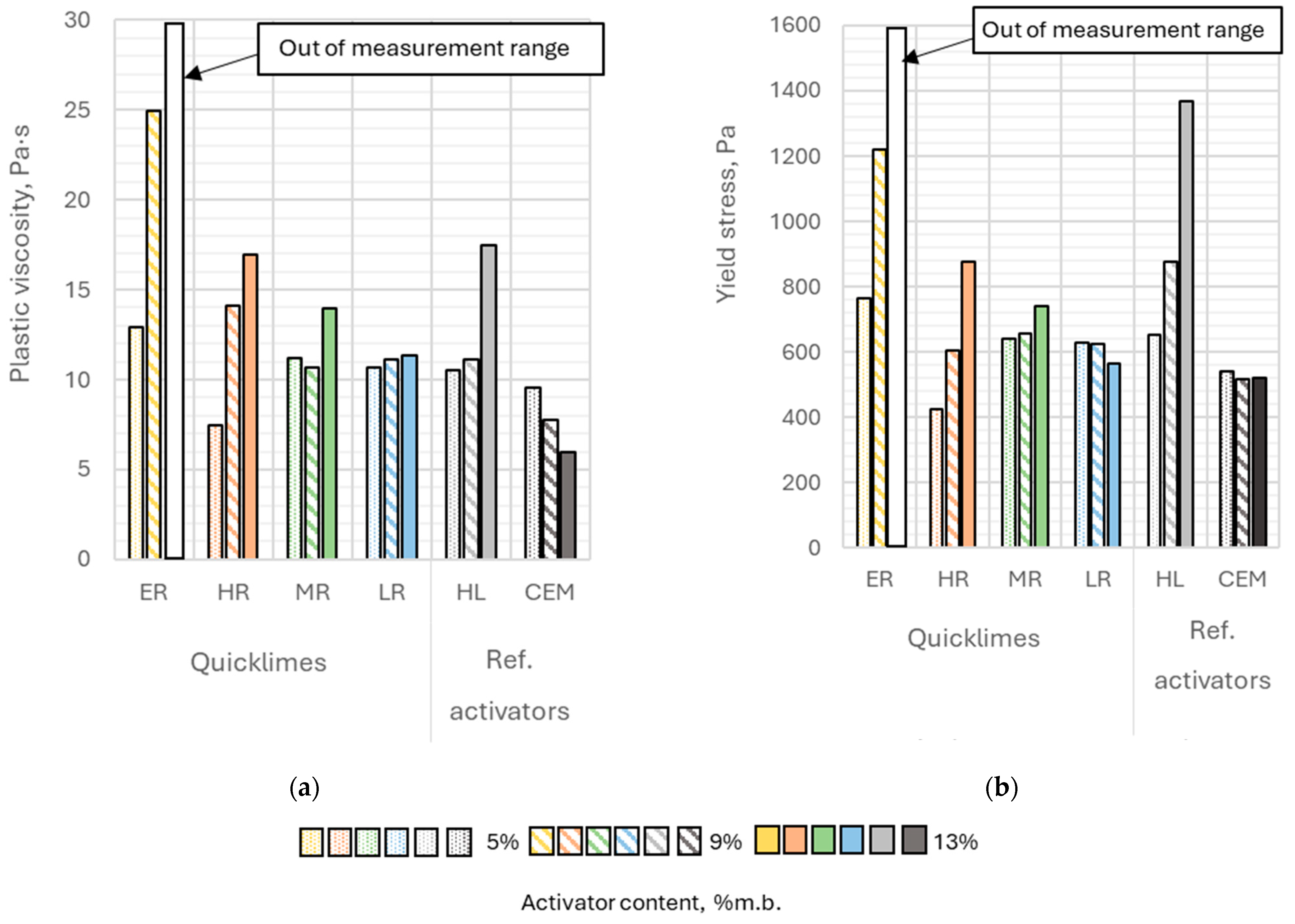

4.1. Viscosity and Yield Stress

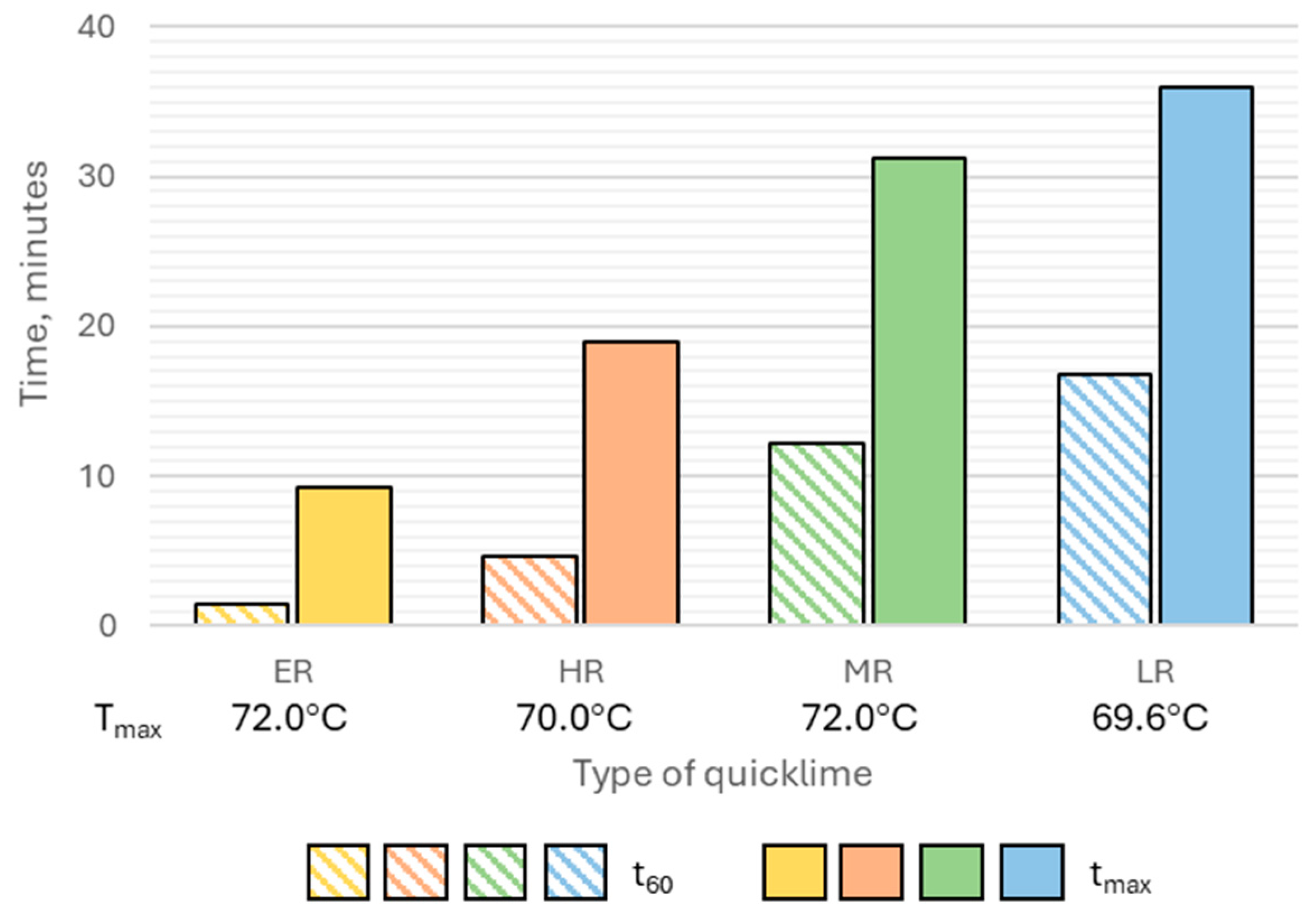

The plastic viscosity of the pastes ranged from 6.0 to 25.0 Pa·s (

Figure 7a). The highest measured plastic viscosity was observed for the paste containing 9% extremely reactive lime, while the lowest was for the paste with 13% Portland cement; however, this paste was not the least fluid. The fluidity of the paste with 13% extremely reactive lime was so low that a reliable measurement could not be obtained for this case. The plastic viscosity of this paste exceeded the measurement range of the rheometer.

The yield stress of the analyzed pastes ranged between 426 and 1366 Pa (

Figure 7b), indicating high variability within the examined set of results. The highest value (1366 Pa) was recorded for the binder containing 13% hydrated lime by binder mass. Similar to the plastic viscosity, the yield stress of the paste with the highest content of extremely reactive lime exceeded the measurement range of the viscometer. The lowest yield stress (426 Pa) was observed for the paste with 5% highly reactive lime content, which was more than three times lower than the yield stress of the paste containing 13% hydrated lime by binder mass.

Alkaline pastes with Portland cement exhibited a similar yield stress regardless of the amount of activator used. In contrast, binders activated with calcium hydroxide showed a significant increase in yield stress as the activator content in the binder increased. Increasing the content of this activator from 5% to 13% by binder mass resulted in more than a twofold rise in the yield stress value. A similar trend was observed when using highly reactive quicklime and lightly burned lime as activators.

The content of extremely reactive lime in the binder exhibited the strongest influence on both the plastic viscosity and yield stress of the analyzed pastes. Increasing the content of this activator from 5% to 9% by binder mass resulted in nearly a twofold increase in both yield stress and plastic viscosity. A similarly strong effect on yield stress was observed with changes in the content of hydrated lime. Increasing the content of hydrated lime led to yield stress increases of 34% (from 5% to 9% by mass) and 109% (from 5% to 13% by mass). A comparable trend was noted for highly reactive lime, with yield stress increasing by 42% (from 5% to 9% by mass) and 105% (from 5% to 13% by mass).

In contrast, plastic viscosity increased more rapidly with the addition of highly reactive lime compared to hydrated lime. The pronounced impact of ER and HR lime on the rheological properties of the pastes could be attributed to their high reactivity among the considered types of quicklime and their relatively large specific surface area.

Interestingly, hydrated lime showed a surprisingly strong influence, despite its lower specific surface area compared to other activators. This could be explained by its significantly lower bulk density compared to other activators, resulting in the largest volume for hydrated lime at the same mass.

Changes in the content of MR and LR lime had only a minor effect on the plastic viscosity and yield stress of the pastes containing these activators. For low reactive lime, even a slight decrease in yield stress (by approximately 10%) was observed when its content increased from 9% to 13% by binder mass.

A clear correlation was observed between the chemical reactivity of CaO and the rheological behavior of the activated slag pastes. Mixtures containing extremely reactive quicklime exhibited the greatest plastic viscosity and yield stress, both increasing sharply with CaO content. This behavior can be attributed to the rapid hydration of CaO, which not only accelerates the formation of Ca(OH)2 and early Ca-rich hydrates but also leads to intensive water absorption during the exothermic hydration process. The resulting reduction in free water and the increase in solid volume fraction enhance interparticle cohesion and friction, thereby increasing viscosity and yield stress. In contrast, pastes prepared with moderately or low-reactive quicklime showed a slower rise in rheological parameters or remained relatively stable, maintaining higher workability.

These observations indicate that the reactivity of CaO affects not only the kinetics of hydration but also the structure of the liquid phase and the intensity of particle–particle interactions. The rapid consumption of mixing water by extremely and highly reactive quicklimes significantly reduces the volume of the free liquid phase, increasing the solid concentration and limiting the hydrodynamic separation between particles. As a result, interparticle contacts become more frequent and frictional resistance rises, leading to the formation of a semi-rigid, cohesive network within the suspension. This interpretation is supported by the rheological measurements, where the most pronounced increases in plastic viscosity and yield stress were recorded for pastes containing the most reactive quicklimes, confirming that water depletion and intensified particle interactions are key factors controlling the flow behavior of CaO-activated slag binders.

4.3. Initial and Final Setting Time

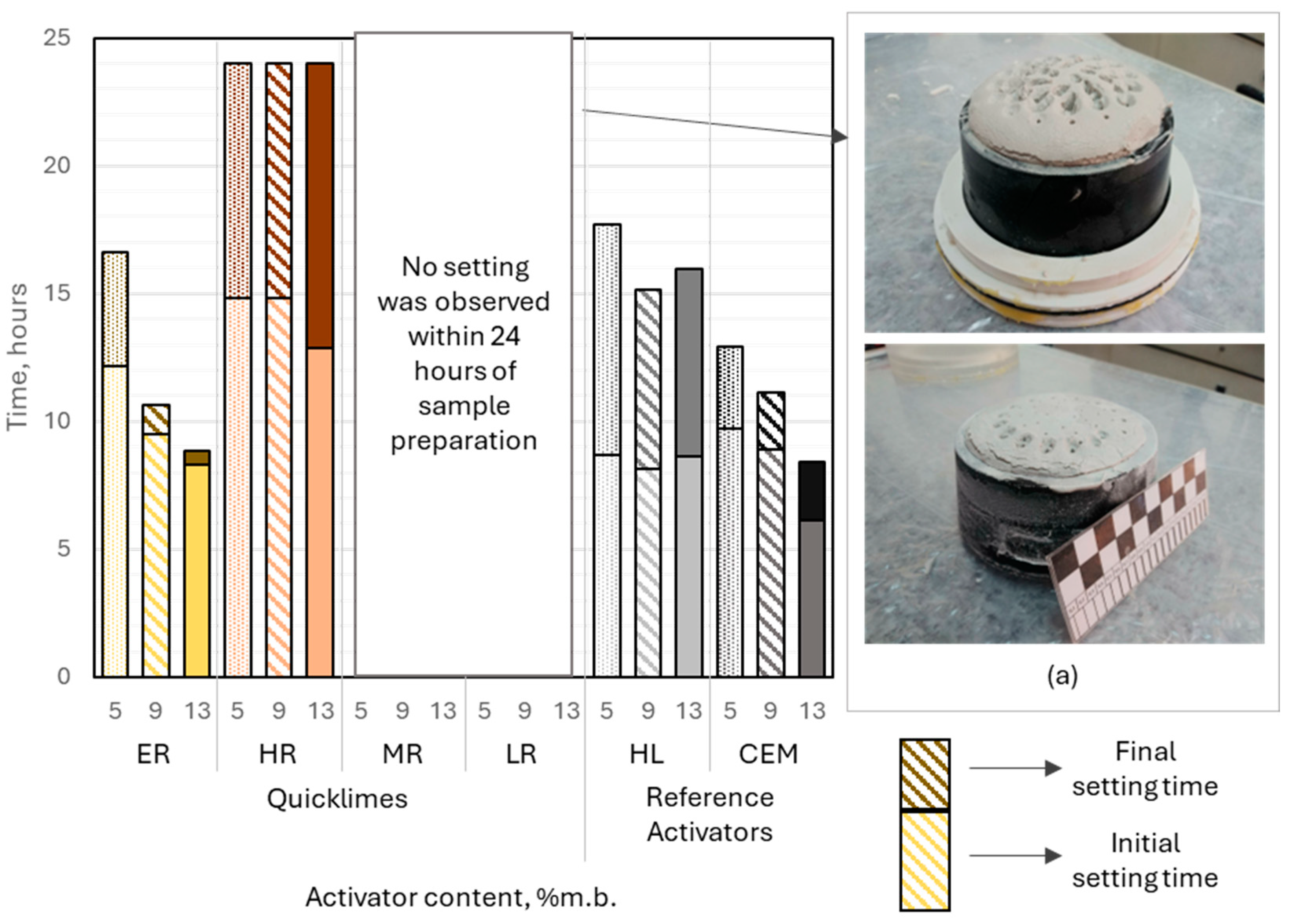

The setting process of CaO-activated binders was highly influenced by the environment in which it occurred—whether in water or in air. Samples containing moderately or low reactive lime did not exhibit setting properties in water within 24 h of preparation, even when the lime content relative to the binder mass was minimized. Instead, these samples demonstrated pronounced and uncontrolled expansion of the paste, driven by the hydration of calcium oxide due to abundant water availability from the surroundings.

When the deformation of the paste was constrained using a Vicat ring, significant internal stresses developed in the forming microstructure of the material, leading to partial damage. This was evident in the cracks observed on the sample surfaces, particularly near the walls of the Vicat ring (

Figure 9). The expansion was so intense that it prevented the development of a stable material structure within the first 24 h after sample preparation.

Extremely reactive CaO-activated binders demonstrated setting behavior under water curing conditions. The initial setting time ranged from approximately 8.2 to 12.1 h, with activator dosages of 9% and 13% (by binder mass) yielding results comparable to those of binders activated with hydrated lime. A significant reduction in setting time was observed as the activator content increased, dropping from 4.5 h at 5% dosage to 30 min at 13% dosage. Importantly, no measurable expansion of the paste was noted during water curing, indicating stable volumetric behavior of the binder.

Binders activated with highly reactive lime demonstrated initial setting times that were relatively insensitive to variations in activator dosage, ranging from 13 to 15 h. The final setting time of these binders, under water curing conditions, was not achieved within 24 h of sample preparation. Minor paste expansion was observed at activator dosages of 9% and 13% (relative to binder mass), which likely extended the time to initial setting and prevented the attainment of final setting within 24 h.

All binders incorporating reference activators exhibited successful setting behavior in water. The quantity of hydrated lime had no significant impact on the initial or final setting times. The initial setting time of these binders ranged from 8 to 9 h, with the setting times, understood as the difference between the initial and final setting times, between 7 and 9 h. Slag–alkali binders incorporating Portland cement at 5% and 9% (binder mass) showed initial setting times similar to those of hydrated lime-activated systems, at approximately 10 and 9 h, respectively. Increasing the cement dosage to 13% significantly shortened the initial setting time to 6.1 h. The setting time of slag-cement binders was less influenced by the activator dosage, ranging between 2 and 3.5 h.

The analyzed slag–alkali binders were characterized by a longer initial setting time compared to commonly used general-purpose cements. Considering their composition, the analyzed binders can be compared to blast-furnace cements CEM III/B and CEM III/C, in which blast-furnace slag may constitute 66% to 95% of the binder’s mass. Currently, the European cement market offers only CEM III/B cements. According to data published by cement manufacturers, the initial setting time of CEM III/B cements typically ranges from 240 to 300 min. In comparison, the binder with the shortest initial setting time among those analyzed contained 13% Portland cement, with an initial setting time of 366 min. Based on its composition, this binder could be classified as a blast-furnace cement CEM III/C.

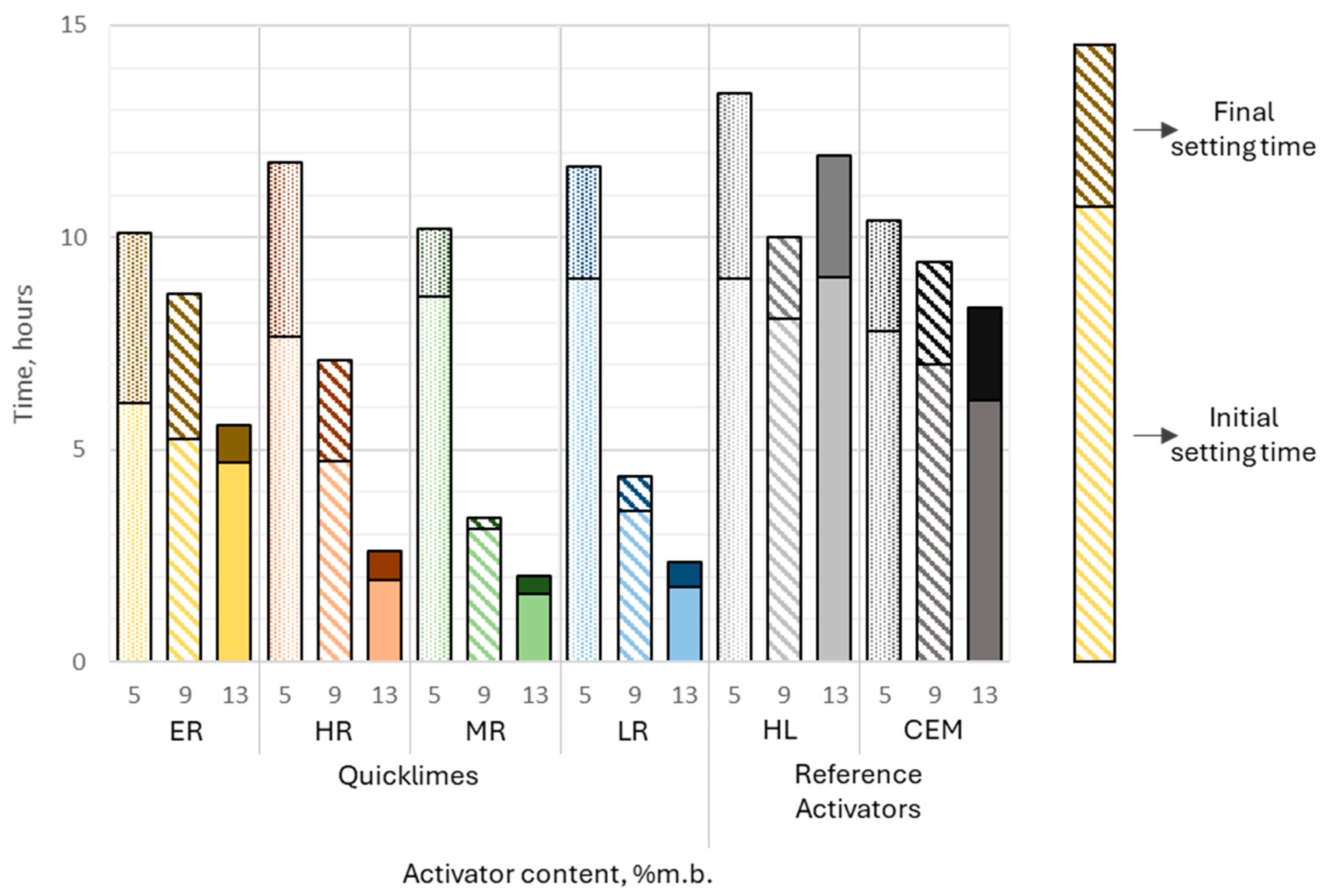

Adjusting the curing conditions had a significant impact on the setting kinetics of alkali-activated slag binders, particularly for binders incorporating calcined lime. The initial setting time of these binders exhibited strong sensitivity to the activator dosage, ranging from 1.6 to 9 h. Similarly, the setting time was markedly influenced by the activator content, spanning from 2 to over 11 h, demonstrating the critical role of activator content in controlling the setting behavior of these binders.

For all pastes containing quicklimes, setting times significantly decreased with increasing activator dosage. The most pronounced reductions were observed in pastes containing highly reactive (HR), moderately reactive (MR), and low-reactive (LR) limes. For MR lime, the initial setting time decreased sharply from approximately 8.5 h at 5% activator content to around 2 h at 13%, while the final setting time dropped from over 10 h to approximately 2 h. Similarly, LR lime pastes showed a substantial reduction, with the initial setting time decreasing from 9 h at 5% to 2 h at 13%, and the final setting time dropping from over 11 h to slightly above 2 h. The HR samples followed a similar trend, with initial setting times decreasing from approximately 12 h at 5% activator content to 2 h at 13% (

Figure 10).

In contrast, pastes activated with extremely reactive lime (ER) exhibited smaller reductions in setting times. For ER lime, the initial setting time decreased slightly from approximately 6 h at 5% to 5 h at 13%, while the final setting time dropped from 10 h to 5.5 h.

Reference activators behaved differently. Hydrated lime (HL) produced consistent setting times, with initial times ranging from 8 to 9 h and final times from 10 to 13 h. Samples containing Portland cement (CEM), however, displayed a linear decrease in both initial and final setting times as activator content increased from 5% to 13%. Initial setting times decreased from approximately 8 h to 6 h, while final setting times dropped from 10 h to 8 h.

Tian et al. [

14] reported that CaO-activated pastes with 8% CaO (by mass) exhibited an initial setting time of approximately 6–7 h and a final setting time of 8–9 h under the same testing conditions. These values varied depending on the source of GGBFS; however, no details were provided regarding the reactivity of the quicklime or the specific surface area of the GGBFS used. The results obtained by Tian et al. align with those observed in this study for samples containing 9% highly reactive lime, despite Tian et al. employing a significantly higher water-to-binder ratio of 0.5.

For comparison, Yum et al. [

27] reported an initial setting time of approximately 9 h and a final setting time of 19 h for pastes with 4% CaO and a GGBFS specific surface area of 2970 cm

2/g. When comparing these findings with the results from this study and Tian et al. [

14], it can be concluded that the specific surface area of GGBFS plays a crucial role in influencing the hydration kinetics of CaO-activated GGBFS binders.

As mentioned, increasing the content of HR, MR, and ER limes in the binder from 5% to 13% resulted in more than a fivefold reduction in the time to the initial setting of the binders. This could be attributed to the acceleration of the hydration process of blast-furnace slag. However, this effect was not observed in binders containing highly reactive lime, which served as the basis for formulating an alternative hypothesis.

The slaking reaction of quicklime was accompanied by a noticeable decrease in paste fluidity, as free water in the paste was consumed during calcium oxide hydration. According to the slaking reaction Equation (2), hydrating 1 g of CaO required approximately 0.3 g of water. At lime contents of 9% and 13% by binder mass, this corresponded to 12 g and 18 g of water, respectively, accounting for 8% to 15% of the initial water content in the analyzed pastes.

The results presented in

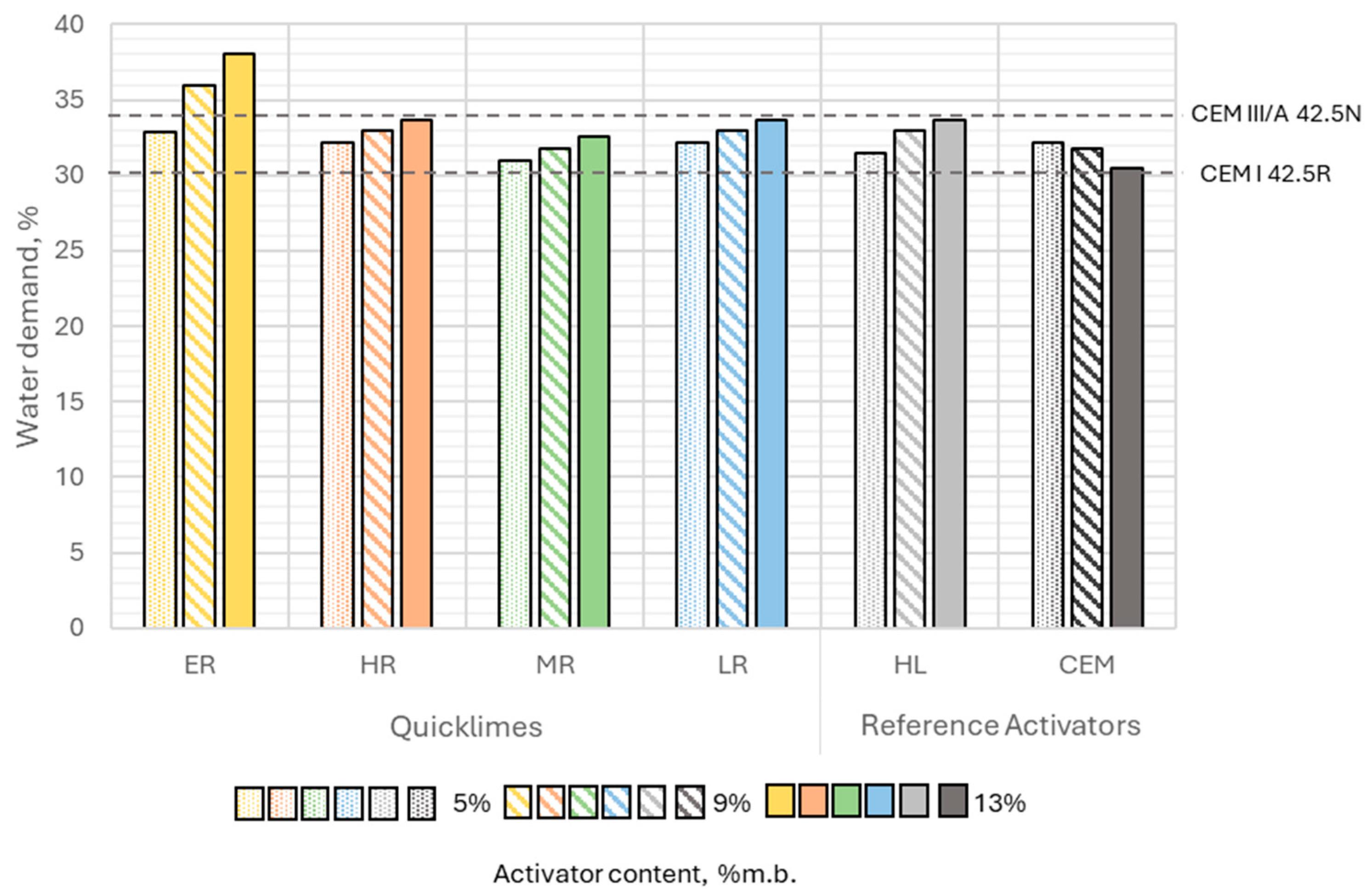

Section 3.2.2 regarding the reactivity of highly reactive lime indicated that pastes containing this quicklime should reached their maximum temperature within 10 min of mixing. This suggested that a significant portion of calcium oxide hydrated during mixing, before the paste was placed in the Vicat ring. The resulting decrease in fluidity was observed during the determination of the binder’s water demand (

Section 4.2) using the Vicat apparatus and was offset by increasing the water content. Consequently, binders containing ER quicklime at 9% and 13% by binder mass exhibited the highest water demand among the analyzed pastes.

In contrast, pastes with other types of quicklime behaved differently. According to reactivity tests, the hydration of these limes entered its critical phase much later. This delayed hydration was not accounted for during the determination of the water required to achieve standard consistency, as this test was typically completed within 5 to 6 min of mixing.

As a result, the observed acceleration in the setting process of binders activated with quicklimes, other than extremely reactive lime, was likely due not only to changes in the hydration kinetics of GGBFS but also to the extended slaking reaction of burnt lime. This reaction, occurring in the presence of limited free water, caused a gradual loss of paste fluidity over time, which in turn accelerated stiffening.

This hypothesis was supported by the observation that binders with reference activators, as well as those with highly reactive lime, exhibited a less pronounced effect of activator content on setting times and the time to initial setting. Additionally, the initial setting times of binders containing hydrated lime, determined in air, were comparable to those determined in water, with differences ranging from 1.9% to 4.5%. In contrast, binders with Portland cement showed more significant differences between initial setting times determined in air and in water. These binders began setting 4% to 27% faster in air than in water.

4.4. Long-Term Strength Development

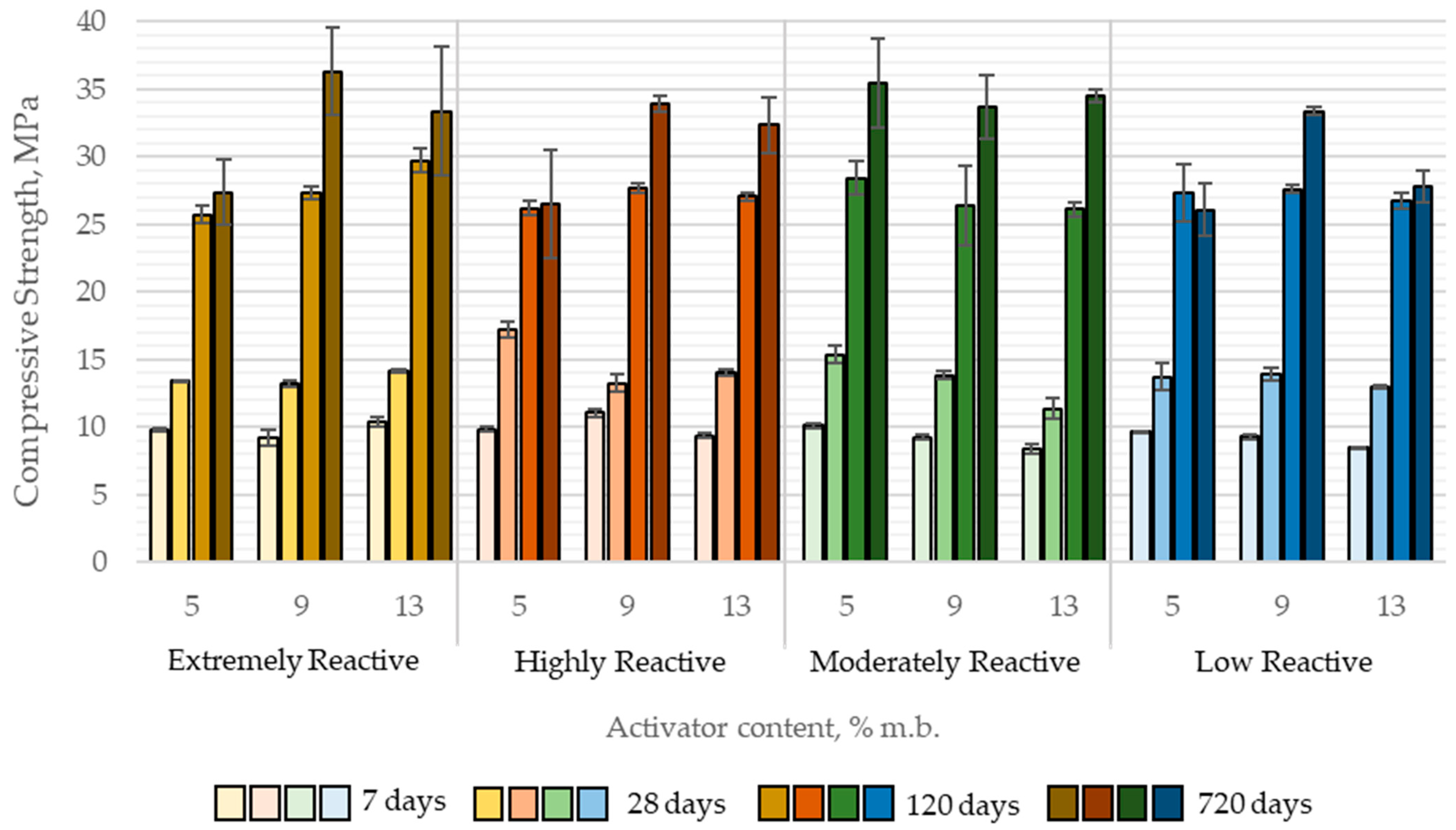

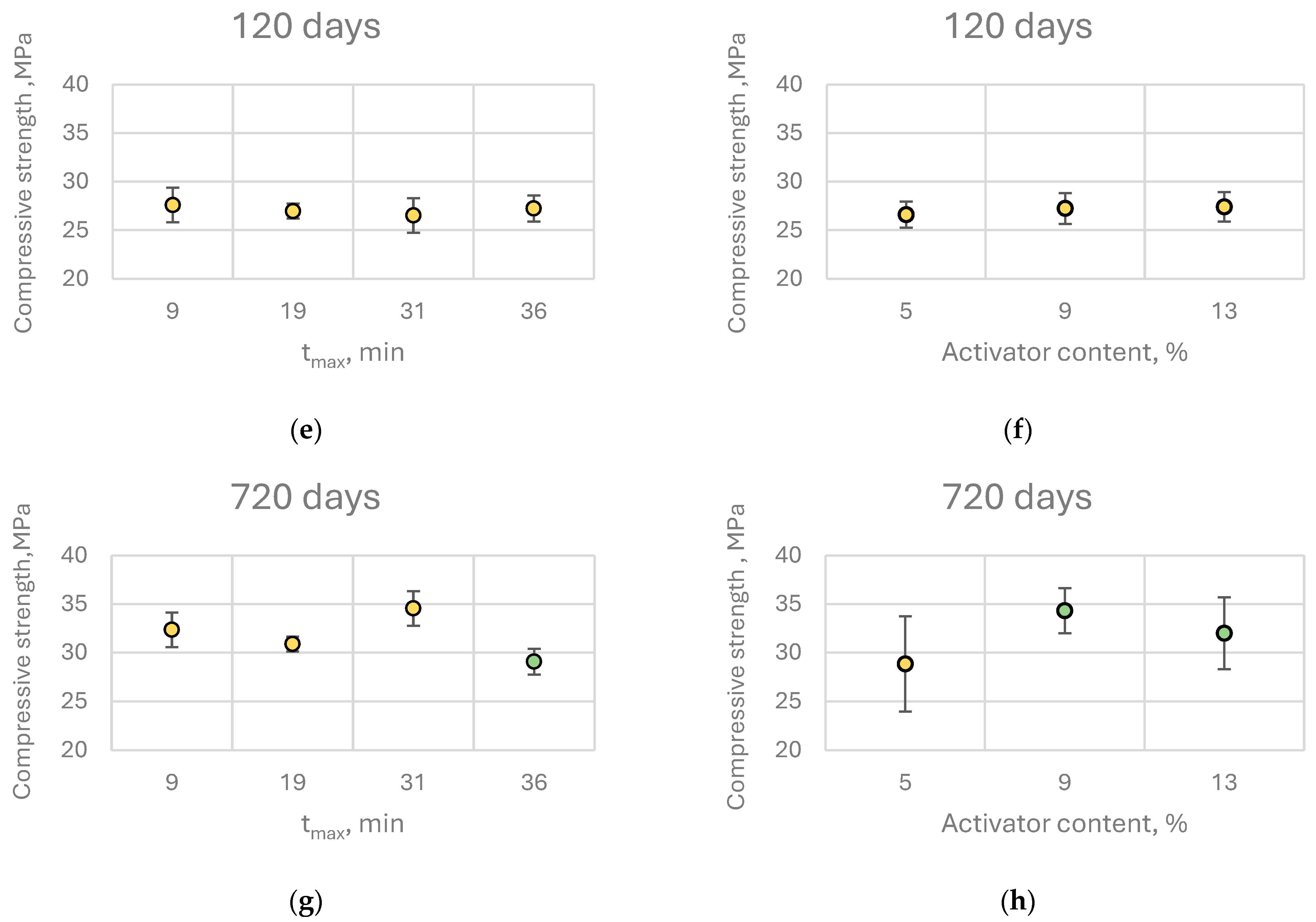

The average compressive strength of alkali-activated paste samples with quicklime ranged from 8.4 to 11.1 MPa at 7 days of curing, 11.4 to 17.2 MPa at 28 days, 25.7 to 29.7 MPa at 120 days, and 26.1 to 36.3 MPa at 720 days of curing (

Figure 11).

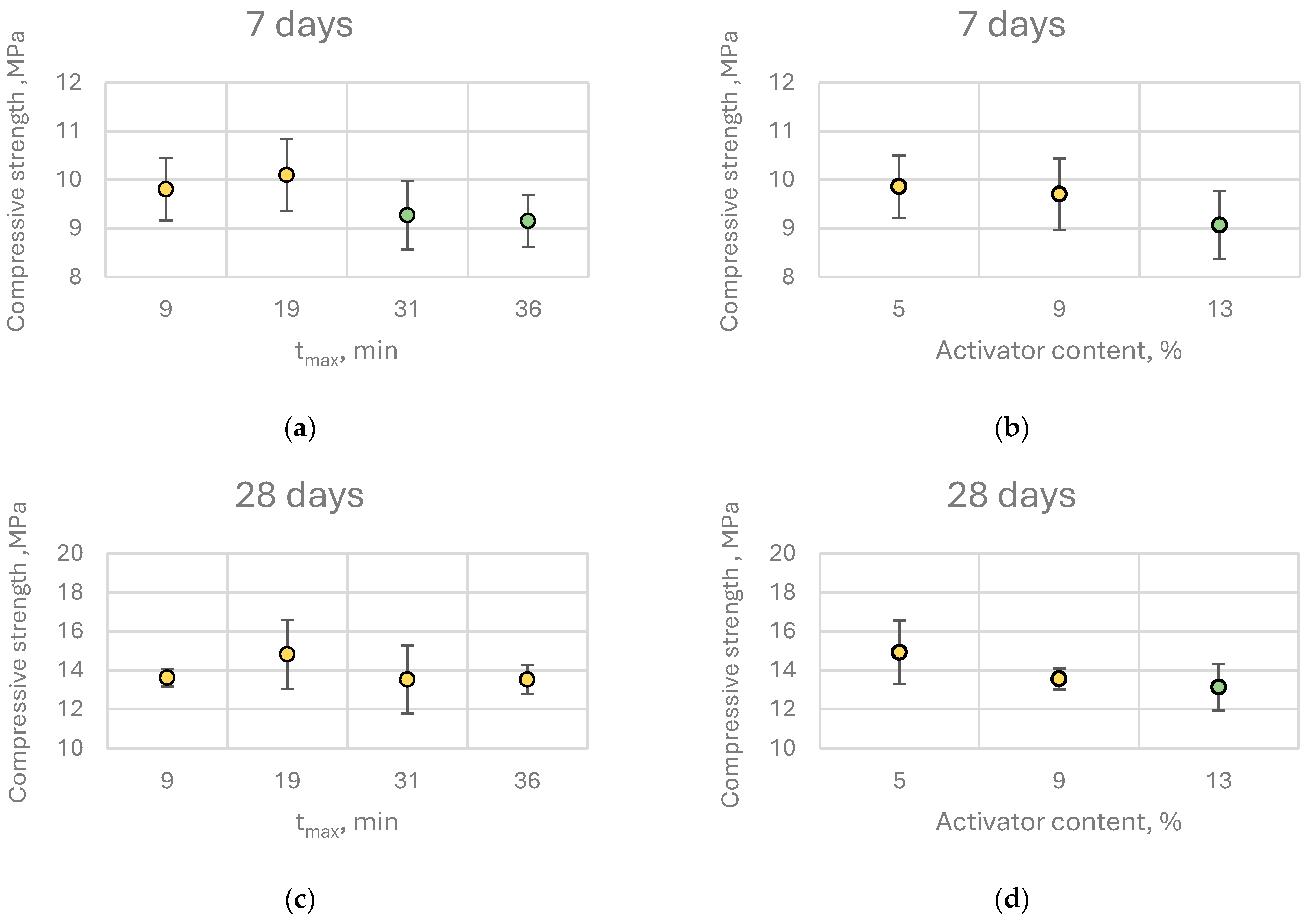

Given the extensive dataset comprising 192 individual measurements, a comprehensive statistical analysis was carried out to assess the influence of lime reactivity on binder properties. Initially, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was applied, with tₘₐₓ (time to reach maximum temperature) selected as the quantitative descriptor of quicklime reactivity. To facilitate group comparisons, tmax values were rounded to the nearest whole minute, yielding representative reactivity classes: 9 min for extremely reactive (ER), 19 min for highly reactive (HR), 31 min for moderately reactive (MR), and 36 min for low-reactive (LR) quicklimes. The primary goal of MANOVA was to determine whether statistically significant differences existed among these groups. Following MANOVA, a Scheffé’s post hoc test was conducted to identify homogeneous subsets and to clarify which groups exhibited statistically significant differences in their performance.

The results of the MANOVA analysis demonstrated that both quicklime reactivity and its content in the binder had a statistically significant influence on the compressive strength of CaO-activated pastes in three out of four tested time intervals, specifically at 7, 28, and 720 days. Notably, at 120 days, neither the reactivity of the quicklime nor its content showed a statistically significant effect on compressive strength.

The direction and magnitude of these effects varied with curing time. At early ages (7 and 28 days), an increase in quicklime content and a decrease in reactivity (higher tₘₐₓ values beyond those for highly reactive lime) were generally associated with a slight reduction in compressive strength. However, the magnitude of these differences was negligible from a practical perspective. For instance, increasing the quicklime content from 5% to 13% (by binder mass) led to a compressive strength decrease of 0.68 MPa at 7 days and 1.80 MPa at 28 days.

Interestingly, this trend did not persist at later curing stages. At 120 days, compressive strength was independent of both quicklime reactivity and content, while at 720 days, pastes containing higher quicklime content exhibited significantly greater compressive strength. This may be attributed to long-term processes such as carbonation, which could enhance the mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag binders containing CaO. Furthermore, at 720 days, no strength reduction was observed in relation to decreasing quicklime reactivity; in fact, the highest compressive strength was recorded for pastes activated with moderately reactive (MR) quicklime (

Figure 12).

Post hoc analysis (Scheffé’s test) revealed that increasing quicklime content beyond 9% by binder mass did not result in statistically significant improvements in compressive strength at any curing age. The same analysis indicated that for early-age (7 days) and 28-day strength, it is preferable to use highly reactive quicklime at the lowest investigated dosage, although the differences among groups were minor. Consequently, from a practical engineering standpoint, within the studied range of quicklime reactivity and content, these parameters do not exert a substantial influence on the early compressive strength of the binder.

In contrast, when considering the long-term compressive strength (720 days), samples containing LR quicklime exhibited significantly lower compressive strength compared to those activated with other types of quicklime. Conversely, the results also indicated that increasing the quicklime content from 5% to 9% of the binder mass was beneficial for the mechanical properties of CaO-activated composites, leading to a substantial increase in average compressive strength—nearly 20% at 720 days.

This finding indicates that curing conditions strongly influenced the microstructural evolution and long-term strength of CaO-activated composites. After 120 days of curing under water, the samples were transferred to air and stored under laboratory conditions, where exposure to atmospheric CO

2 enabled gradual carbonation. The two-stage curing regime therefore facilitated both initial hydration under saturated conditions and subsequent carbonation during air storage. In binders containing higher CaO content, the larger amount of residual Ca(OH)

2 in the matrix provided an additional source of reactive calcium for carbonation. As reported previously [

44], the formation of CaCO

3 from Ca(OH)

2 leads to a reduction in porosity, as the reaction product occupies a greater solid volume. A similar densification process likely occurred in the present study, where controlled carbonation during the air-curing stage improved the microstructural compactness and, consequently, enhanced the compressive strength of the pastes.

On the microstructural level, carbonation likely induced partial decalcification of the C–S–H phase and the precipitation of finely crystalline CaCO3, mainly calcite and vaterite, within gel pores and interparticle voids. These reaction products filled capillary spaces and refined the pore network, leading to a more compact and continuous matrix. The formation of CaCO3 at the C–S–H interfaces also contributed to improved particle bonding and reduced permeability. Such controlled carbonation resulted in a denser, more cohesive microstructure, which explains the observed long-term increase in compressive strength.

The influence of carbonation on the mechanical properties of CaO-activated composites is strongly time-dependent. At early stages of curing, when the pore structure remains relatively open, the system is particularly susceptible to CO

2 ingress, which facilitates rapid carbonation of Ca(OH)

2 and the formation of finely dispersed CaCO

3. This early carbonation can significantly enhance the compactness of the microstructure and contribute to the rapid development of mechanical strength. Recent findings by Jeon et al. [

45] confirmed that the introduction of NaHCO

3 as an in situ carbonation agent in CaO-activated slag systems more than doubled the 3-day compressive strength, demonstrating the potential of controlled early carbonation to accelerate hardening.

As hydration and carbonation progress, CaCO3 progressively fills capillary pores, and the matrix becomes denser and less permeable, thereby reducing the rate and extent of subsequent carbonation. At later ages, the ongoing but slower carbonation process continues to refine the microstructure, though its effect on strength becomes less pronounced. Thus, carbonation exerts its greatest influence at early curing stages and remains a secondary, yet beneficial, mechanism contributing to the long-term densification and strength evolution of CaO-activated GGBFS binders.

However, further increasing the CaO content to 13% of the binder mass did not produce any additional improvement in compressive strength, indicating an upper limit to the beneficial effect of quicklime dosage in these composites. At early ages, this plateau results from physicochemical constraints of slag activation under high Ca2+ concentrations. At elevated CaO contents, the pore solution rapidly becomes saturated with Ca2+ and OH− ions, and further additions of CaO do not increase the pH of the system, providing no additional benefit in promoting GGBFS dissolution. Simultaneously, rapid CaO hydration consumes a significant portion of the available mixing water, while the early precipitation of a dense Ca-rich layer on slag particle surfaces restricts ion diffusion and limits further reaction progress. This limitation could potentially be mitigated under accelerated or in situ carbonation conditions, where the excess Ca(OH)2 present in high-lime mixtures might contribute to early strength improvement through controlled CaCO3 formation.

At extended curing times (up to 720 days), the strength plateau likely results from the restricted carbonation of residual Ca(OH)2 within the hardened matrix. As the composite becomes progressively denser and less permeable, the ingress of CO2 is hindered, limiting further CaCO3 precipitation and microstructural densification. Consequently, despite the higher CaO content, no measurable long-term strength enhancement was observed, as the combined effects of Ca2+ saturation, early water depletion, and reduced permeability prevented additional C–S–H or carbonation-induced strengthening.

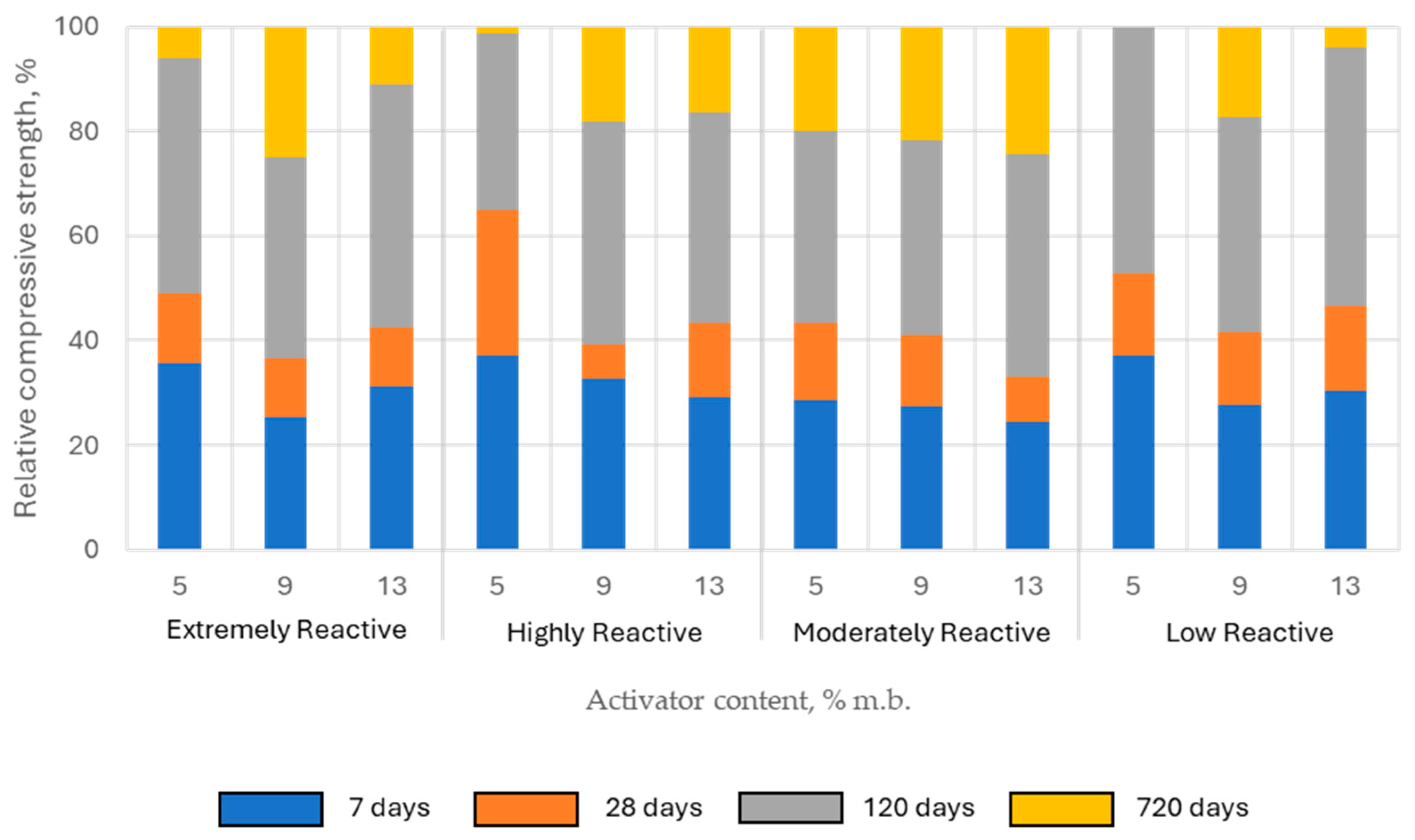

The compressive strength of pastes activated with quicklime increased gradually over time. On the 7th day of curing, the compressive strength of the tested samples ranged from approximately 24% to 37% of the 720-day strength, which was considered the reference level for further analysis (relative compressive strength). At 28 days, the relative compressive strength of the samples was mostly within the range of 33% to 52%. The only exception were the samples with highly reactive lime in the lowest content (5% of binder mass), where the relative compressive strength was higher than 60%. However, the most significant increase in mechanical properties was observed between 28 and 120 days of curing. After 120 days of curing, the strength gain slowed considerably. At this stage, the relative compressive strength of the samples ranged from 75% to 100% (

Figure 13).

Lower activator content favored higher early-age relative compressive strength (7 and 28 days), while increasing the lime content in the binder resulted in greater compressive strength gains over longer periods. This observed trend aligns with the hypothesis that carbonation plays a significant role in shaping the mechanical properties of CaO-activated composites.

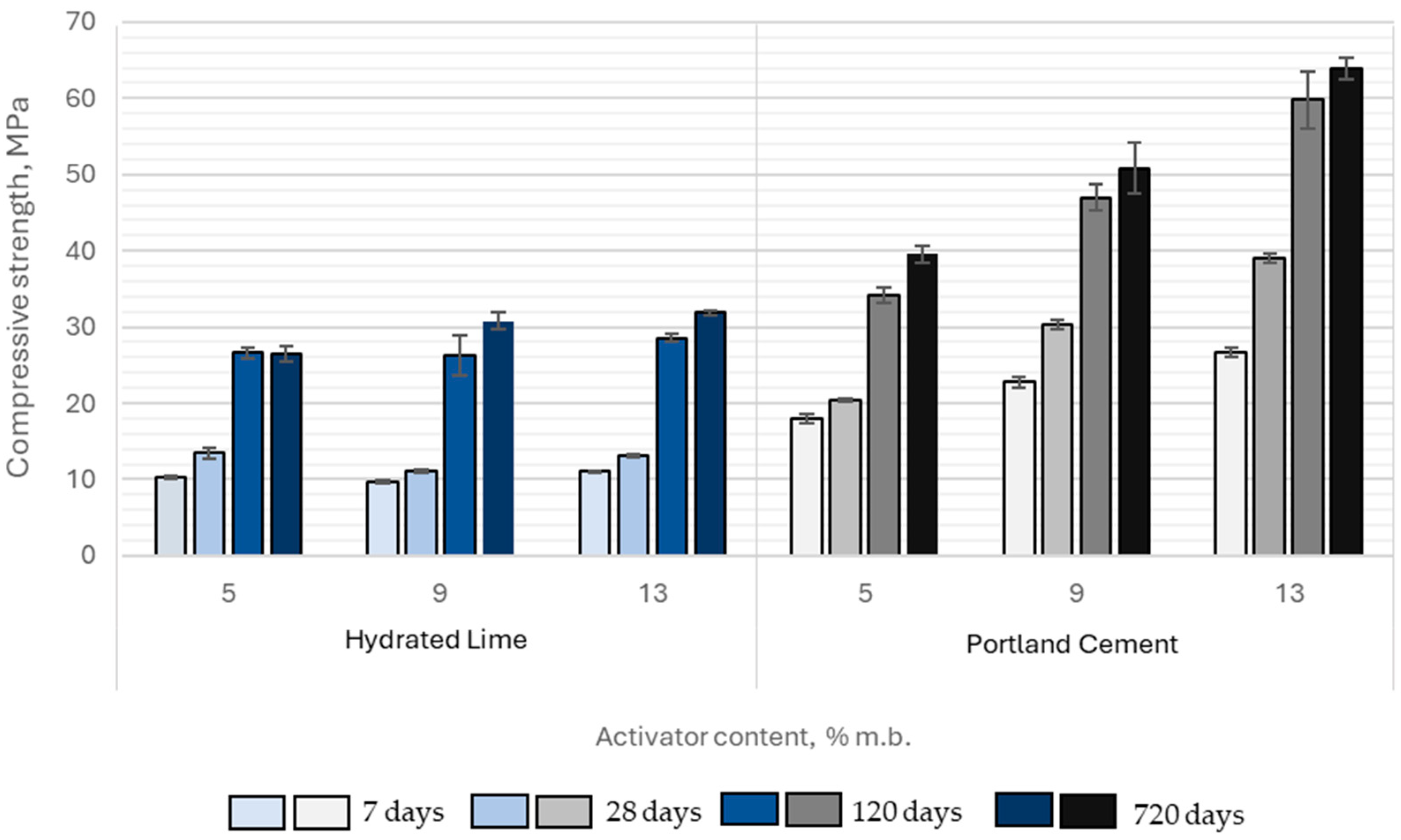

The average compressive strength of samples containing hydrated lime and Portland cement ranged from 9.7 to 26.7 MPa at 7 days of curing, 11.1 to 39.0 MPa at 28 days, 26.4 to 59.8 MPa at 120 days, and 26.5 to 63.9 MPa at 720 days. The highest strengths were achieved when Portland cement was used as the activator.

The compressive strength of paste samples activated with Portland cement was significantly higher compared to those activated with hydrated lime. At 7 days, the strength of cement-activated pastes exceeded that of hydrated lime-activated samples by 76% to 141%, while at 28 days, this difference ranged from 51% to 196%. Although the gap between the two groups narrowed slightly with extended curing time, it remained substantial. After 120 days, the compressive strength of Portland cement-activated samples was still 28% to 109% higher, and at 720 days, the difference ranged from 49% to 100%. Moreover, the magnitude of these differences increased proportionally with higher activator content in the binder (

Figure 14).

The compressive strength of samples activated with Portland cement increased proportionally with its content in the binder. In contrast, increasing the hydrated lime content above 5% by binder mass did not produce any significant improvement in compressive strength. This behavior can be explained by both chemical and microstructural constraints governing slag activation. At around 5% Ca(OH)

2, the pore solution becomes saturated with Ca

2+ and OH

− ions released from the activator and early slag dissolution. Further additions increase ionic strength without substantially elevating pH, which remains lower than in Na-based activators and therefore does not further accelerate slag dissolution. The excess Ca(OH)

2 tends to remain undissolved and may become incorporated into the developing C–S–H structure. In addition, surplus Ca

2+ promotes the early formation of Ca-rich surface layers on slag particles, which limit ion diffusion and hinder continued reaction and densification of the binding phase. As a result, a practical upper limit of approximately 5% Ca(OH)

2 can be considered optimal for strength development under the tested mix design and curing conditions. Similar observations were reported by Tang et al. [

46] and Lei et al. [

47], who found negligible improvements in compressive strength when increasing Ca(OH)

2 dosage beyond 3–5% of binder mass in alkali-activated slag mortars.

A similar mechanism was also observed in the case of CaO activation, although it occurred at a different activator dosage, as discussed earlier. In CaO-activated systems, the plateau in compressive strength appeared at around 9% CaO, which corresponds to a comparable degree of Ca2+ saturation in the pore solution. Despite the different hydration kinetics between Ca(OH)2 and CaO, both systems exhibited a similar physicochemical limitation: excess calcium availability and rapid hydroxyl ion release promoted surface passivation and reduced slag dissolution, thereby constraining further C–S–H formation and limiting the potential for additional strength development.

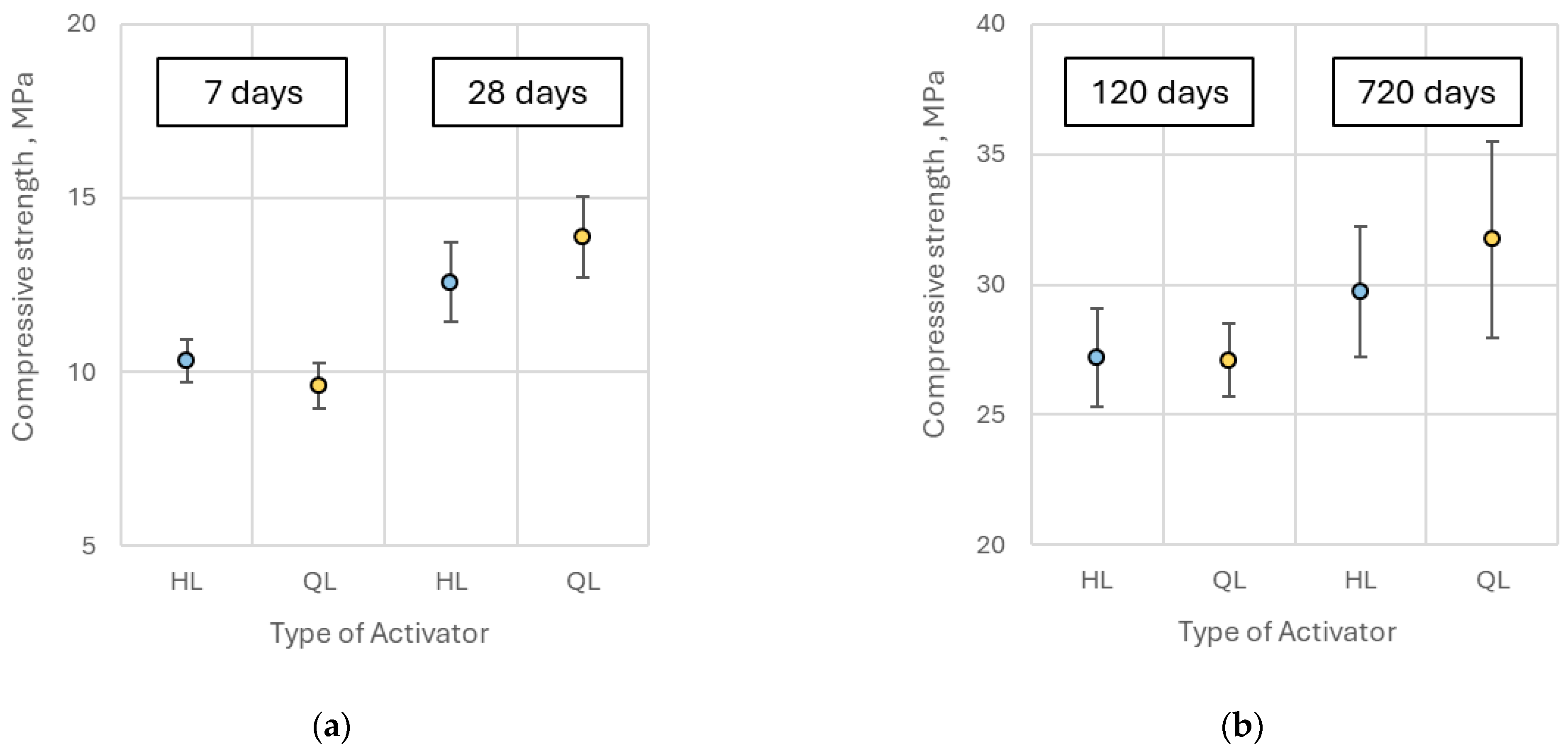

The compressive strength of pastes containing quicklime was comparable to that of hydrated lime-activated samples at 7, 28, and 120 days of curing, with no statistically significant differences observed. However, after approximately two years (720 days), specimens containing 9% and 13% quicklime demonstrated approximately 15% higher compressive strength relative to those activated with hydrated lime (

Figure 15). Overall, the substitution of hydrated lime with quicklime did not lead to a substantial enhancement in compressive strength of the alkali-activated slag pastes, consistent with observations reported by Kim et al. [

13].

The 28-day compressive strength obtained in this study was approximately 50% lower than the values reported in the literature for pastes with the same water-to-binder (

w/

b) ratio, but cured under air conditions (T = 23 °C, RH > 99%). Specifically, Yum et al. [

15] reported an average compressive strength of 27.3 MPa, while Sim et al. [

26] observed a mean value of 25 MPa. In comparison, the average compressive strength achieved in this research was only 13.9 MPa.

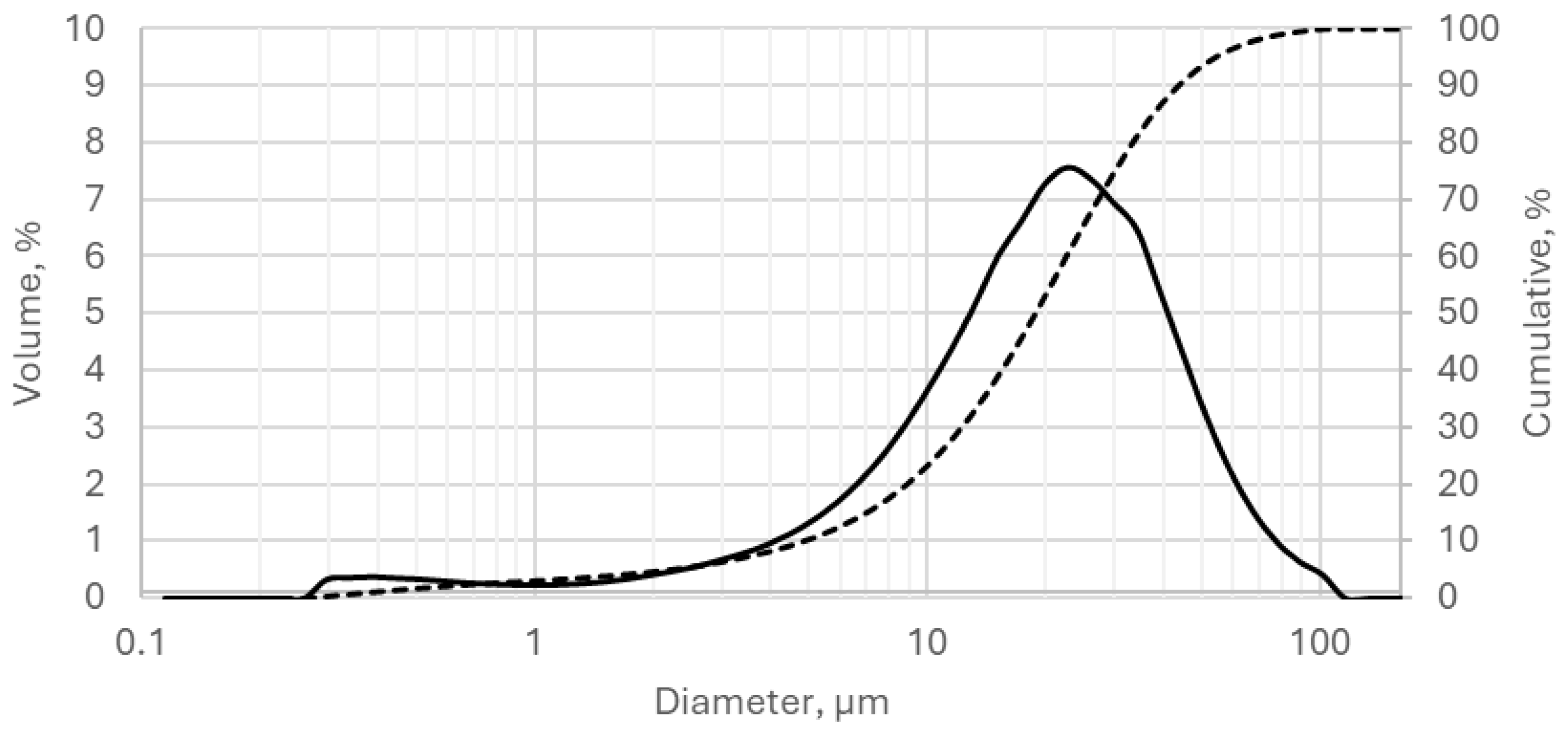

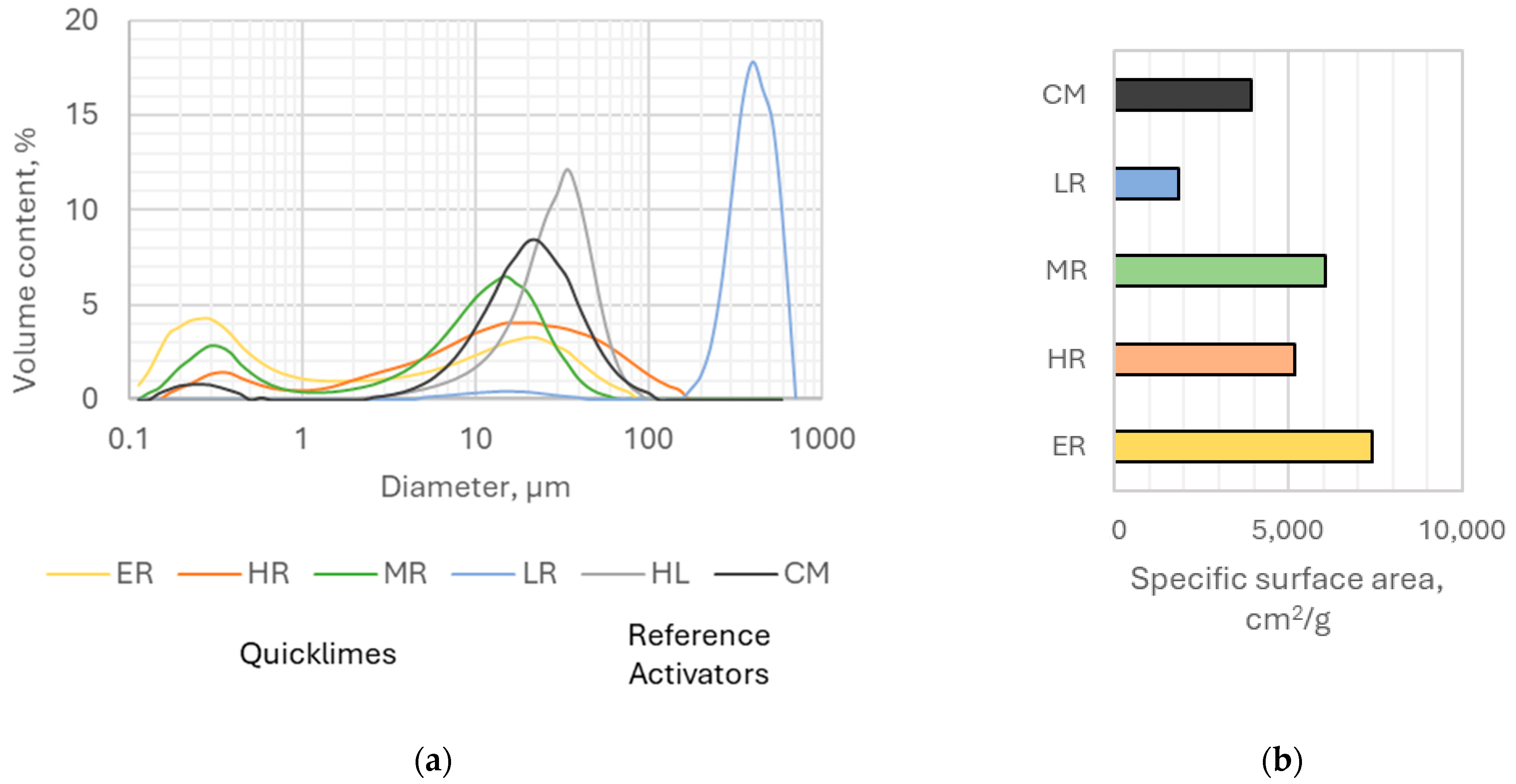

This significant discrepancy may be attributed primarily to differences in the particle size distribution of GGBFS and the applied curing conditions. Although neither Yum nor Sim provided data on the specific surface area of the slag used, they reported mean particle sizes of 15 μm and 9.7 μm, respectively. In contrast, the GGBFS employed in this study had a considerably coarser mean particle size of 22.3 μm, which likely contributed to its reduced reactivity and lower mechanical performance. The limited surface area restricts slag dissolution, reducing ion availability for C–S–H formation and slowing early hydration kinetics. Similar effects were reported by Burciaga-Díaz [

31], who demonstrated that increasing the Blaine fineness of GGBFS from 360 to 450 m

2 kg

−1 significantly enhanced dissolution, produced denser reaction products, and improved 90-day compressive strength.

Moreover, as discussed previously, the effect of carbonation on the mechanical properties of CaO-activated slag binders must also be considered. Samples cured under air conditions, as in the studies by Yum and Sim, were exposed to natural carbonation, which may have enhanced their strength. Conversely, samples in this study were water-cured for 120 days, preventing carbonation and possibly limiting strength development.