1. Introduction

Governments and their experts typically attempt to resolve the challenges of (vocational) education by exploring models that have worked elsewhere. Martínez-Izquierdo and Torres Sánchez explain, “This search for solutions beyond the limits of the system itself leads to a policy transfer process, which involves reforms or the articulation of new policies based on models which are already a successful reality in other locations” [

1] (p. 16). Policy transfer is a complex and extensively researched concept whose definition depends on the academic discipline and perspective of the author [

2]. For the purposes of this article, we understand it as a process that encompasses ideas, ideology, practices, and institutions and one that involves multiple actors [

3]. Thus, it is a continuum that can incorporate various influences, from voluntary ones to more coercive ones [

4].

In this article, we discuss the challenges posed by the re-introduction of apprenticeship in Slovenia initiated by the launch of the European Alliance for Apprenticeship in 2013. The European Union (EU) supports the introduction of a collective skill formation system inspired by Germanic vocational education and training (VET) systems, and Slovenia shares many of its features, including social partnership and work-based learning [

5]. Yet, attempts to develop a sustainable partnership have proven to be a constant challenge. Understanding the reasons behind this is one of the foci of the research, which has closely monitored the implementation of apprenticeships in Slovenia after 2017.

We seek to understand conditions that enhance the sustainability of social partnerships. Since gaining independence in 1991, Slovenia has been developing its VET system, drawing inspiration from the Germanic skills formation model while maintaining some of the previous features, such as the permeability of the education system and the commitment to the idea of public education and welfare state. Our central thesis posits that the challenges Slovenia faces are closely tied to the complexities of policy borrowing. Methodologically, we were inspired by the work of Rappleye and Komatsu [

6], who investigated whether the United States could successfully adopt Japanese Lesson Study, and if not, what factors hinder such transfers. Their research employs an interpretative approach to contextual analysis and extending it through the notion of a system’s onto-cultural fabric. This framework offers a cautiously optimistic view of transferability, suggesting that while specific practices may resist transplantation, the foundational “soil”—the underlying ontology—can be cultivated and transformed.

In examining the “soil” of Slovenia’s VET system, into which the new apprenticeship model has been introduced, we also aim to contribute to a deeper understanding of both the potential and limitations of Germanic collective skill system transfer. Despite shared characteristics, the Germanic model remains difficult to transfer [

7]. We argue that even systems like Slovenia’s, which exhibit structural similarities, encounter significant barriers to successful adoption.

The article is divided into three parts. In the first part, we discuss the aspects of sustainable policy transfer in the field of vocational education. The second part presents the context of the research from a comparative angle, followed by the presentation of the results, discussion of the research questions, and conclusion.

2. The Importance of Context in Policy Transfer

Policy borrowing is a form of policy transfer [

8], which “works best when there is some similarity between the different educational systems as well as between the political ideologies guiding reform within them” [

9] (p. 5). In other words, there should be as many similarities as possible in the contexts of transferring and receiving systems [

10]. Portnoi [

8] emphasizes that policy borrowing is shaped by global power dynamics, particularly the influence of the Global North and international governance organizations. Local actors play an active role in mediating, adapting, or resisting borrowed policies, and that these processes are embedded in complex cultural, historical, and institutional contexts. In comparative education, context is a highly debatable issue, as vividly emphasized by Rappleye [

11] (p. 223): “No sooner do we set to the task of analyzing transfer processes than we run headlong into the issue of context, which has beguiled, stymied, and divided comparative work on transfer since the field’s inception.” Rappleye urges researchers to “think in greater depth about context” [

11] (p. 228). In comparative education, context usually refers to administrative, economic, technological, historical, political, and national characters [

12]. The concept of culture has also been emphasized [

13,

14] as cultural incompatibilities that can decisively impede the policy process [

15].

Schweisfurth et al. [

6] distinguish between two principal approaches to the treatment of context in comparative education research. The first views context holistically, as an ecosystem in which various elements are interconnected and mutually reinforcing [

16] (p. 571). This represents interpretivist reading of context [

17] (p. 427) and includes Rappleye and Komatsu’s [

6] concept of onto-cultural context, which emphasizes the embedded cultural and ontological dimensions of educational systems. The second approach adopts a positivist or functionalist stance, treating context as a collection of pre-defined, measurable variables.

In addition to these paradigms, context is also critically examined through the lens of power relations [

18], particularly in relation to critiques of Europe’s colonial legacy and the dominance of Western epistemologies in comparative education [

19]. For post-socialist countries such as Slovenia, democratization has often been framed as a “return to Europe”—a symbolic and structural alignment with Western European models of market liberalization and political pluralism [

20]. This orientation is reflected in Slovenia’s tendency toward educational borrowing: for example, the comprehensive reform of its school system in the early 1990s was grounded in comparative data from Western European countries and used to legitimize the proposed changes [

21]. Accordingly, Slovenia can be situated among those countries where policy borrowing plays a more prominent role than policy lending [

9] (p. 347).

In the globalized world, policy transfer rarely occurs between a donating and receiving country; rather, it involves the worldwide diffusion of specific patterns [

3,

19]. Beyond their influence on one-to-one transfers, contextual factors are also crucial in a global alignment process [

2] (p. 191). Steiner-Khamsi [

22] has elaborated on third-generation studies on transfer that shifted the focus of research from bilateral policy transfer to the internationalization of national educational processes. Due to globalization, international organizations play an increasingly crucial role in the formation of global and European education policies. They have been identified as ‘central nodes for policy diffusion’ that are able to transfer policies between countries while promoting their own agendas [

23]. The adaptation of certain policies is often a condition to be fulfilled to receive financial or political gains [

23].

3. Transfer in the Context of the Europeanisation of Education

The adoption of the Lisbon Strategy in 2000 marked the starting point in establishing a European education policy defined by common goals, implementation tools, and financial resources, although the EU formal competencies in the field of education are limited by the subsidiarity rule [

24]. Due to the process of Europeanisation, policy borrowing has become one of the main processes initiating educational change, and knowledge transfer is the key element of policy transfer incorporated into numerous policy initiatives and tools. In VET, policy transfer in the global context is a highly relevant topic because there are numerous stakeholders involved: at the international level, the World Bank, the ILO, and the OECD are the main actors, and at the European level, key stakeholders are the European Council, the European Commission and the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) [

9]. From the perspective of any European government, it is important not to be “laggard” [

9] (p. 341), which is why they search for best practices and solutions elsewhere. But for researchers the impact of the Europeanisation on VET has been much more controversial [

25]. Barabasch, Bohlinger, and Wolf [

9] (p. 347) critically claim that the development of VET is “a result of Northern economic interests transmitted via VET policies.” Similarly, Martínez-Izquierdo and Torres Sánchez [

26] (pp. 7–8) show that in European VET, the improvement in the governance of the system and the inclusion of new actors are recurrent themes in European policy texts. With a new focus on work-based learning, the authors indicate that the EU supports the Germanic collective skill formation system governance regime as a model of good practice. Among others, the EU supports a system that includes the following elements: (a) different stakeholders are systematically included as active participants in governance and change management; their involvement is regulated; (b) sustainable funding mechanisms and shared funding and investment are in place; (c) cooperation takes place between schools and companies at the national, regional, sectoral, and micro levels; (d) social dialogue is perceived as a tool to enhance quality; and (e) VET policies respond to labor market needs and societal demands, thereby necessitating the development of anticipation tools which supports labor market actors to avoid potential skills mismatch by labor market monitoring and analysis of supply and demand [

27].

The transfer of any policy is always a matter of interpretation, modification, and re-contextualization, which can also cause the ideas behind the policy to be undermined or altered [

28]. The extant literature also highlights how European ideas are embedded deeply into the domestic perspective [

29]. Moreover, policy transfer can take years or decades for adjustments to be fully achieved because the policy is not implemented until local actors accept and implement it [

14].

4. The Sustainability of Policy Transfer in Dual VET and Apprenticeship

Given the high failure rate of policy transfer [

3,

30], the question arises as to conditions that can realistically support its sustainable implementation [

9] (p. 342). Valiente and Scandurra [

31] stress the great importance of contextual conditions, which should be considered when transferring dual systems. Among them, the involvement of employers, institutional capacity to monitor training activities, the reputation of VET, and the cooperation of social partners are central. In VET, policy transfer has been extensively researched, particularly on the issue of the transfer of the German dual vocational training system. This stream of research indicates that successful transfer largely depends on the country’s ability to pay attention to manifold aspects of the context—that is, a detailed analysis of the context should accompany any implementation of an imported policy [

32]. A recent synthesis of studies on the exportability of the German dual system performed by Li and Pilz [

2] is valuable because it proves the complexity and challenges faced by such an endeavor. In their study on the transfer of the German dual system to more distant countries such as China, India, and Mexico, Pilz and Wiemann [

33] found that local actors, such as employers, young people, public officials, representatives of the education system, and trade union representatives, determine which elements of VET may be transferred. Among the conditions for the sustainable implementation of VET policies, the role of local stakeholders is particularly important; thus, their perspectives must be taken into consideration and extensively elucidated. Furthermore, Rappleye [

11] draws attention to human dimensions, which involve resistance factors, including actors who strive to maintain the existing status quo.

In comparative (vocational) education, there is no definitive list of contextual factors to be considered, nor a methodological tool capable of capturing all potential enabling or constraining elements [

34]. Within an interpretative framework, the development of such a tool is inherently unattainable, as it would fail to account for the deeper, culturally embedded layers of a system that must first be recognized and understood. From the perspective of the receiving country, a thorough and nuanced exploration of these contextual dimensions becomes indispensable. This recognition forms the foundation of the study presented in this article.

5. Contextual Background

Historically, politically and culturally, most of current Slovenian territory was a part of the Germanic sphere. In VET, up to the first half of the twentieth century, the alternating training system was the prevailing model of vocational socialization in this part of Europe [

35]. In Slovenia, modern apprenticeship began to develop after the Second World War in response to the shortage of a skilled labor force. Apprentice law was adopted in 1946, which defined the role of an apprentice who was on the basis of a learning contract employed in industry, craft, or trade. In 1952, a division between apprentices and vocational schools was enforced; apprentice schools were organized in companies, while vocational schools organized practical training in school workshops. In 1967, this distinction was abolished, and all schools gained the status of secondary schools [

36]. The responsibility for VET was gradually transferred to the state. VET became financed by the state, which also planned its scope, determined the programs, and provided conditions for its implementation. The late 1970s saw the introduction of a career-oriented educational system. The reform created a model of comprehensive upper secondary education aimed at enabling the entire population to obtain a common basis for further education, personality growth, and higher cultural standards and at directing students towards work or an appropriate branch of further education. Later, the reform was criticized for not sufficiently preparing students for entry into the labor market, and employers did not cooperate in the reform process [

37]. The ideological goal of making a country and its educational system more compatible with Western and North European political, sociocultural, and economic ideas, was very much present. After Slovenia gained independence, part of its “path to Europe”, was also the reform of VET. Based on both the negative experience accumulated from career-oriented education and comparative research—Austria and Germany being the main reference countries—a conceptual design for a new VET system was developed. In 1996, new legislation on education was adopted. The development of social partnerships and dual VET was particularly highlighted, but still maintained a strong emphasis on general education subjects and broad technical knowledge in all types of vocational education, thereby maintaining the transition options between general and vocational education at upper secondary level and study opportunities for graduates of vocational programs [

38].

Three-year upper secondary vocational programs—which train students to take on occupations at the level of skilled workers in the craft and service sectors—are the focus of our attention, which, between 1996 and 2006, were provided in dual as well as in school-based learning routes. In 2006, the dual route was abolished because it was observed that it did not provide apprentices with equal educational standards. The school-based route prevailed, but it maintained a relatively large proportion of work-based learning and social partnership foundations. Since 2013, with the launch of the European alliance for apprenticeship and its reinforcement through Riga conclusions [

39] aimed also at promoting work-based learning, European stakeholders and member states have done much to extend the use of this form of learning [

5]. This external push was the reason why apprenticeship at the time again became a policy priority for the Slovenian government. The dialogue between the government and social partners resulted in the adoption of the Law on Apprenticeship [

40] and the (re)introduction of apprenticeship only applied to the 3-year vocational programs. The law conceptualized apprenticeship as a learning route towards a vocational qualification, the main difference from the school-based route being the amount of time spent in companies (minimum 50% instead of 20%). Apprentices must achieve all the learning outcomes prescribed by the education program.

The preparation of the law took place simultaneously with a Cedefop’s country thematic review [

5], a policy learning activity which aimed to “identify strengths and enabling factors, focused on the challenges and developed action points towards quality apprenticeships” [

5] (p. 6). The review concluded that due to pre-existing social partnership and a relatively large amount of work-based learning, Slovenia has many enablers on which the implementation could build (such as examples of established cooperation between schools and companies, competence-based approach in occupational standards and learning outcomes defined for all VET programs, the existence of intercompany training centers, etc.). However, many challenges were identified as well: lack of clear vision of apprenticeship, limiting apprenticeship to 3-year programs, lack of clear division of responsibilities among ministries, and funding that mainly comes from EU-funded projects [

5].

In 2017, a pilot apprenticeship scheme was also launched, which lasted three years. The pilot scheme, as well as further gradual implementation of the apprenticeship into Slovenian education, has been continuously and intensively monitored. The research plan of the scheme was approved by the National Council for Quality and Evaluations in Education, and it was carried out by the National VET Institute in cooperation with the University of Ljubljana.

5.1. The Characteristics and Challenges of Social Partnerships in Slovenian VET

Social dialogue is a process of exchange between social partners to promote consultation and collective bargaining [

41]. Studies indicate that social dialogue is a complex process that causes challenges in all countries [

42,

43,

44]. Hiim [

44] describes the difficulties in social dialogue in Scandinavian countries, which have been attributed to the school-based nature of their VET systems. However, challenges have also been reported in Germanic countries, where companies, the strongest partners in the dialogue, sometimes lack readiness for cooperation [

45]. Bechter et al. [

42] emphasize the importance of the capacities of the people involved in the dialogue. Capacities refer to formal and tacit knowledge on social dialogue and on the content of the dialogue, communication skills and the positions that the participants hold.

In Slovenia, social partnership has been relevant for the whole system of vocational education at the upper secondary and tertiary levels (short-cycle programs) as well as for the system of recognition of national vocational qualifications for adults. It is defined in the Law on Vocational Education [

46], which stipulates that partners of competent ministries are chambers, organizations, and trade unions that, in cooperation with the ministries, conduct activities related to vocational education. Among ministries, the main partner is the Ministry of Education. Therefore, the Law on Organization and Financing of Education in the Republic of Slovenia [

47] stipulates that social partners delegate their representatives to the National Professional Committee for Vocational and Technical Education, the main professional body to guide the development of VET in the country, and to participate in decision-making activities. The Law on Apprenticeship [

40] regulates the role of the chambers. Most of the legalization is under the Ministry of Education’s competency, the only exception being the Law on National Vocational Qualifications [

48], which falls under the Labor Ministry’s jurisdiction. Based on this law, the minister of labor formally approves the occupational standards, which are the basis for all public formal VET programs in the country. The minister of education is responsible for the approval of all formal education programs, for the maintenance of the public school network, and for the provision of financial means.

At the implementation level, the key actors are schools that prepare school curricula, learning and assessment plans for apprentices, assess the apprentices, award certificates, and provide support to companies. Companies are required to provide quality training, financial awards for apprentices, and safety at work. Chambers announce learning places, keep all records, and co-sign learning agreements between apprentices and companies. They are also required to support companies, provide promotions, and organize intermediate exams. Trade unions are responsible for protecting the rights of apprentices. Apprentices retain their formal student status, allowing them and their families to maintain all the benefits that the state offers to children, youth, and families.

Social partnerships never fully took off in practice. Doubts about its feasibility were first expressed in the evaluation conducted in the late 1990s [

49], in which the authors explained that the government had deliberately not given social partners a greater role in decision-making and implementation, as they needed time to develop their organizational, financial, and personnel capacities. A decade later, another evaluation found that their capacities were still weak [

21] (pp. 230–231), causing the abolition of the dual system in 2006. The low level of union engagement has also remained a concern [

50]. Recent evaluations [

5,

51] have confirmed that a comprehensive coordinated model has never been put into practice.

The introduction of social partnership in the early 1990s was perhaps one of the more radical interventions in VET, as it challenged a way of acting and thinking that had been intensively enforced in education since the end of the Second World War, when the state gradually “nationalized” education during the socialist era [

37]. Gradually, citizens adopted the mindset that the state is solely responsible for education.

5.2. Social Partnership and Apprenticeship from a Comparative Angle

Cedefop [

52] (pp. 24–26) published a comparative study on mechanisms of interaction between the labor market and the education system. They developed a classification of four typical models of feedback mechanisms [

52] (pp. 47–55): (a) The coordinated model—one in which occupational space dominates—is classified by Busemeyer and Trampusch [

53] as a collective skill formation system (Germany, Austria, Denmark, to a lesser extent Slovenia). (b) The liberal model is found in countries in which occupational/organizational space dominates and is classified as either a liberal or market-led skill-formation system (England, Ireland). (c) The participatory model refers to a strong state role and a focus on schools while maintaining strong ties with the occupational space. It can share some features with the coordinated model (Slovenia), or with the statist model (e.g., France and Finland). (d) The statist model is mostly found in countries that have a clear focus on state-regulated school-based VET (Bulgaria, Estonia, Sweden). It is the most common in Europe.

Another comparative study on institutional–employer partnership in VET [

54] distinguishes between four models of partnership: (a) Model A—the placement model (e.g., Sweden)—in which occupational formation mostly takes place in schools with short placements at work; (b) Model B—the complementary partnership (Germanic systems)—in which schools and companies undertake distinct roles in conveying particular forms of knowledge. These roles are coordinated and complement each other so that partners share the responsibilities for the educational program; (c) Model C—the network model (certain examples in the UK)—which is characterized by weak classification between institutions and employers, whose roles are more interchangeable and less bounded; (d) Model D—a workplace immersion model (UK, the United States)—in which occupational formation takes place primarily in companies with limited opportunities to learn at school. The employing organization takes responsibility for providing all learning activities for practitioners [

54] (pp. 5–10). In Slovenia, schools and companies complement each other, but companies do not have much say regarding the content of learning, which places Slovenia between Models A and B.

From the point of view of Gessler’s [

43] classification of company- and school-based apprenticeships, Slovenia clearly falls under the latter. Gessler explains that a major difference between the two approaches is who has the lead: in company-based apprenticeships, future apprentices apply for an apprenticeship directly with the company, which conducts the selection and formalizes the contract. The apprentice is an employee and receives a wage. In school-based apprenticeships, future apprentices apply at the school which selects candidates. Their placement in companies is formalized; they receive some financial awards, but they are not perceived as full members of the community of practice [

43] (pp. 681–682).

6. Research Problem and Methodology

This article presents part of the research that closely monitored the implementation of apprenticeship in Slovenia after 2017. The main aim of the article is to understand the features and challenges of apprenticeship and social partnership, and on these research questions: Why has a collective skill formation system with a coordinated model of feedback mechanism not been fully implemented and does not seem viable? Under what conditions could social partnership be conceptualized to allow VET, and particularly apprenticeship, to develop in a more sustainable manner? The underlying assumption is that over the years, some decisive contextual factors have been overlooked or disregarded because their detailed analysis and reflection had never been conducted [

2,

32]. Using the interpretative methodological approach, we aimed to identify contextual factors that cause challenges and tensions in existing social partnerships, as well as to provide an opportunity for the stakeholders to find common ground and formulate solutions.

To unfold the manifold decisive factors, I reflected upon the research results of a very comprehensive study in which I was participating as a leading researcher. The study used mixed-methods research combining qualitative and quantitative research techniques [

55]. Priority was given to the qualitative approach and the triangulation of research techniques, because a better understanding of the actors who give meaning to the processes was highlighted [

56]. There are local actors who determine which elements of VET may be transferred [

33], and qualitative and mixed-methods approaches allow for designing research in a more participatory manner and thus giving voice to those who are most affected by change. Moreover, these approaches are also pragmatic, which is relevant in cases where there is also a normative angle to the research [

57,

58].

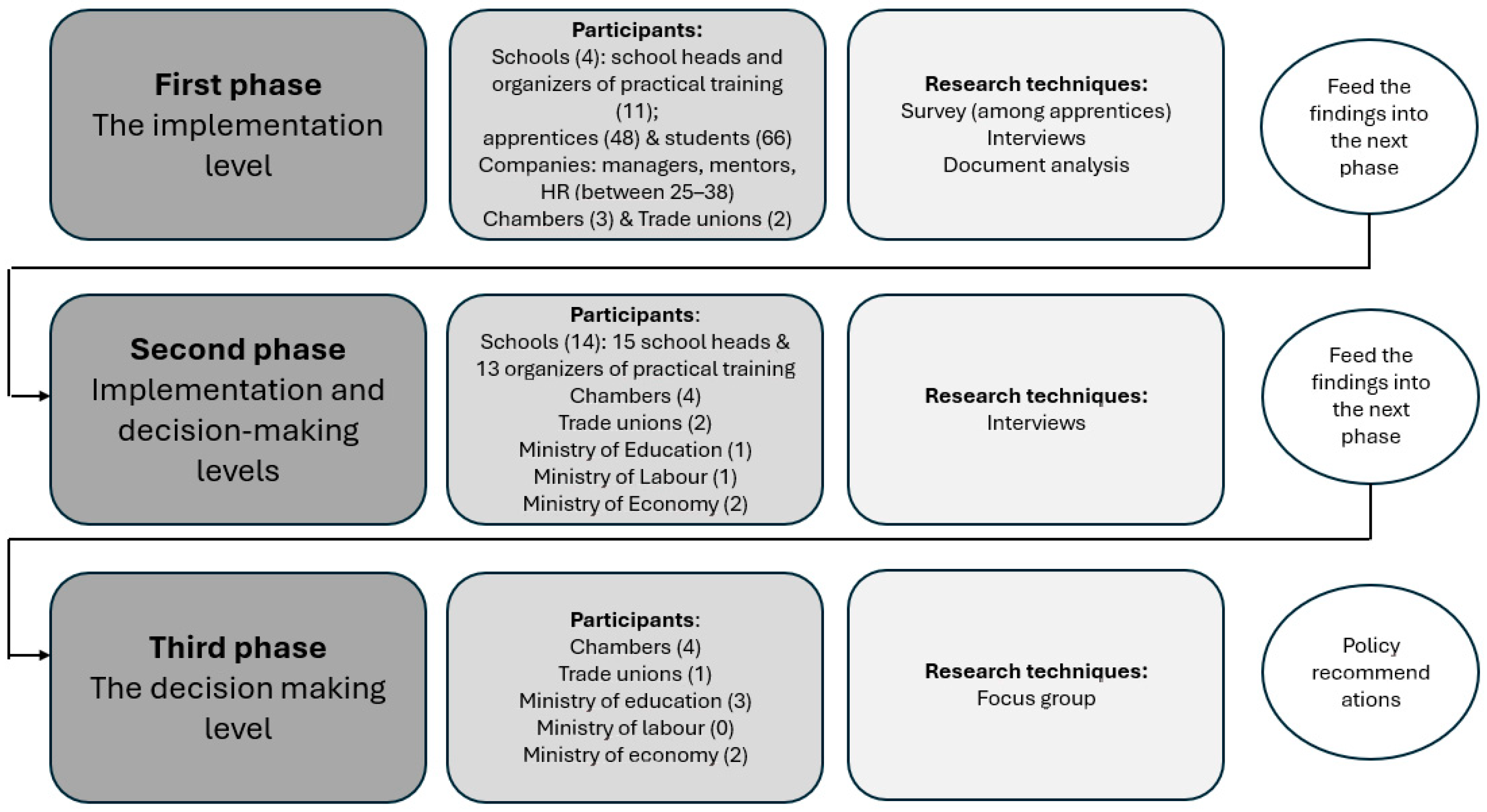

The research was flexible, complex and divided into three phases, and the first two phases were further subdivided into several subphases. Such a design enabled us to feed the findings of a previous stage into the following one. The first phase (with four sub-phases) took place between 2017 and 2020 and monitored pilot introduction of apprenticeship; the second phase took place between 2021 and 2024 and monitored the introduction of apprenticeship to the next generations of programs. The research design (

Figure 1) shows that the first phase focused primarily on the implementation level, the second one added some elements of the decision-making level, and the third one focused solely on the decision-making level.

In the first research phase, various techniques such as interviews, questionnaires, and document analysis were employed. All pilot schools involved in apprenticeships participated in the evaluation, providing education for deficit occupations including Carpentry, Toolmaking, Construction, and Hospitality. Interviews were conducted with school management representatives, chamber representatives, and trade union representatives. Since this was the pilot phase, representatives of all schools participated and representatives of all social partners and ministries. Surveys targeted learning companies and apprentices, the number of participating companies and apprentices fluctuated during different sub-phases, but the response rate was high: in all subphases the majority of apprentices and company representatives participated. During the school years 2017/2018 and 2019/2020 the number of apprentices was 62, 61, and 55, respectively, and 38 companies offered training places.

The qualitative analysis of all interview data followed a six-step process: editing the material, defining coding units, coding, identifying and defining relevant concepts, forming categories, and developing the final theoretical framework. Two university researchers (including the author of this article) and two VET experts participated in each analysis session. To achieve validity of the research, the researchers met regularly: they began with an orientation session during which coding logic was agreed upon and supplemented by a practice round. During the process the researchers met to compare results, identity discrepancies, build shared understanding and refine codes and categories. During the second and third phases, researchers and experts presented findings to participants and facilitated solution development through focus groups involving decision-makers, chamber, and trade union representatives. Survey data were processed using descriptive statistics (frequency, frequency percentage, mean) and presented in structured tables. The χ2 test was employed to identify statistically significant differences between programs.

In the second phase, the evaluation focused on next-generation programs, including qualifications such as Painter, Machine Mechanic, Mechatronic, Car Coachbuilder, Roofer, Glazier, and Electrician. Interviews with school representatives explored their experiences in implementing apprenticeship and identified best practices. The representatives of all schools that offered apprenticeships in the 2021/2022 school year participated, except for the pilot schools. These interviews took place in May and June 2022. Additionally, interviews concerning social partnerships in vocational education were conducted with representatives from social partners and relevant ministries. Four semi-structured questionnaires, tailored to different stakeholder groups, were used. These interviews occurred between December 2022 and July 2023 and were analyzed in the same manner as the first phase.

The third phase involved an in-depth focus group held in October 2023. Decision-maker representatives from the previous phases discussed key issues and divergent opinions that emerged earlier. The primary aim was to interpret the research findings and develop a model of sustainable social partnership and apprenticeship, one that considers the broader cultural, curricular, socio-political, managerial, and economic context of Slovenian society. The synthesis presented in the following chapter includes main findings of the whole study, their interpretation from the research questions’ perspective. In also includes proposals for improving social partnership and apprenticeships nationally. These proposals were made during the focus groups and are a results of the dialogue among researchers, VET experts, and research participants.

7. Results

7.1. Social Partners’ Capacities

The tripartite model of social partnership in Slovenia faces many challenges. We found that trade unions are the weakest link. They are not active in education, thus lacking their own educational agenda and human resources, and were reluctant to cooperate in the research. The absence of trade unions in social dialogue is, however, less visible, since they are formally members of the National Professional Committee for Vocational and Technical Education and participants of different committees. Yet, they tend to delegate teachers or school heads as their representatives, who do not have experience in sectoral trade unions’ interests and perspectives, but rather defend the education sector interests (e.g., contesting apprenticeship for fear of teachers losing jobs). Chambers are recognized by all stakeholders as important partners in Slovenia VET, but they also struggle to find appropriate candidates to cooperate in all activities related to social dialogue. Their candidates delegated to different committees are usually entrepreneurs and active members of the chambers. They receive support (information, guidance, consultations) from the experienced chambers’ staff, but they often lack the time and motivation to become deeply involved in education matters. Moreover, the composition of the committee is such that the chambers are always in the minority. A chamber representative said, “Wherever we go, we are in the minority as the voice of the economy. We are outvoted in any case, but we try to assert our opinions”. The participants in the focus group supported the need for a more balanced composition of the committees. A lack of human resources proved to be a wider problem, which was also happening at the ministry level. The participants said that a lack of human resources and their poorer capacities had a negative impact on the quality of the debate in the social dialogue. “Unfortunately, the quality of our engagement could be much higher”, a participant of the focus group sincerely concluded. Another challenge encountered was the lack of cooperation at the ministry level and the relative reluctance of the Ministry of Labor to assume greater responsibility for participation in social dialogue and contribute to reflections on further development of VET. The results indicate the ministry is willing to maintain its leading role only in relation to active employment policies. The latter falls entirely under its competence, and its representatives are unwilling to discuss it with other ministries. Despite the Ministry of Economy’s limited legal responsibilities, it expressed a willingness to cooperate with the Ministry of Education and its social partners. This research has even contributed to the deepening of their relationship.

7.2. Communication, Mutual Trust, and Government Support

Instead of systemic changes, all participants called for better, more regular and established forms of communication, improvement in mutual trust and respect for each other’s interests: “We have expert councils, commissions, coordination, we have to place new content in already functioning structures that need to be improved”. They also recommended more cooperation among the three ministries and demanded that apprenticeship become a governmental priority. The participants agreed that apprenticeship is no longer a government priority, which they see as one of the main hindrances to its development.

7.3. Epistemological and Organizational Conditions

Apprenticeship in Slovenia was conceived of as a learning route, and no distinctive apprentice programs were set up. Hence, students and apprentices must achieve all the learning outcomes prescribed by rather comprehensively conceptualized VET programs. Stakeholders agree that this is the proper way because it can ensure the same level of quality of qualifications and parity of esteem, which is another challenge for all VET programs. Document analysis and interviews with schools’ and companies’ representatives, however, reveal that it is almost impossible for apprentices—even in excellent working conditions—to achieve all the prescribed learning outcomes. The main obstacle is the structure of the VET programs. All vocational programs namely include general subjects, which comprise 30% of VET programs, and vocational modules rest on the concept of cognitive knowledge [

59] (p. 31) and generic technical skills [

25], with a great deal of emphasis on the theoretical underpinning of vocational competences. Yet, apprentices are obliged to spend at least 50% of their education in companies where learning is by nature more experiential and tacit. This epistemological context opened up many issues and posed many challenges to schools and companies, but the challenge has been relatively well overcome in situations where schools have, over the years, established good cooperation with local companies, in cases where these companies are dedicated to the development of their future workforce and are top companies in their field. In these schools, organizers of practical training are the connecting link between schools and companies who work individually with companies and apprentices and oversee the whole education process, making sure the school- and work-based learning are integrated. Guided by the researchers, the focus group recommended a solution to the problem. The participants were unanimous that VET programs should remain broad, and apprenticeship should still be considered a route, not a distinctive program, because the social status of such programs would be very low. In their opinion, work-based learning should be designed in a more flexible manner, giving space and responsibility to schools, companies, and intercompany training centers to agree upon the apprentices’ learning plans. The idea is inspired by the Swiss tripartite VET model, with one crucial difference: in Slovenia, intercompany training centers are run by larger school centers and not by companies. This solution would confer a more school-based character back to the apprenticeship.

7.4. Disconnections Between Educational, Social, and Labor Policies

Broader labor and social policies also proved to be decisive factors affecting the success and sustainability of apprenticeship. Companies express readiness to take on apprentices, and their motivation has increased in recent years. However, student status in Slovenia is fundamentally a social status related to family benefits and scholarships, allowing young people to engage in temporary part-time work without losing the benefits. Even apprentices who are in training at companies where they receive a modest financial award return to the companies in the afternoons or during holidays and continue to work. The minimum payment for apprentices/students is regulated in both cases, but in the case of part-time work, the minimum hourly rate is much higher than the apprenticeship award. The participants unanimously agreed that the current status of apprentice as student (not as employee) is appropriate. All other arrangements could endanger their social and financial wellbeing and penetrate too deeply into the social order. They would also encounter fierce resistance from student organizations and unions.

7.5. Unsustainable Funding

Finally, funding proved to be another very challenging obstacle in the provision of sustainable apprenticeship. Two issues have been raised in this respect. First, the introduction of apprenticeship in 2017 was mostly financed by EU funds, and the Law on Apprenticeship has not ensured sustainable means of financing after the completion of the EU-supported project. Second, the majority of funding for VET rests on public funds. To provide services to VET, the chambers receive some funds from the state budget; practical training for all VET programs is a responsibility of the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Economy participates. The chambers secure their own funds only for most promotional activities. Yet, the research participants did not support the idea of increased financial input from the companies, and much reluctance to a greater role for private investment in education in general was expressed. Some schools and chambers reported that some companies invest a lot of time and money in their apprentices, but that they are an exception to the rule. The majority of companies are either unable or willing to contribute more, and increased pressure for greater financial responsibilities could be a deterrent factor. The study indicates that the solution should be sought in the direction of establishing tax reliefs or incentives.

9. Conclusions

Our research indicates that the collective skills formation approach, which is also supported by the EU, cannot simply be used as a transfer model, particularly in those countries that also follow the school logic in VET. On the contrary, our research suggests that core principles of social partnership and apprenticeship from other countries can serve as starting points for developing innovative, country-specific solutions. In VET, collective skills formation systems and Germanic approach to VET can serve as a valuable learning opportunity but not as a direct policy transfer activity. To learn from the others and introduce sustainable innovations in VET, it is essential to cultivate a comparative perspective among local researchers, experts, stakeholders, and decision-makers. This approach fosters a deeper understanding of foreign systems as well as of the unique “soil” of the home system—the specific contextual factors that influence vocational education in a particular country. In the areas of social partnerships and apprenticeships, comprehensive and participatory research proved particularly vital. Such an approach enables exploration of a broader contextual framework and reflection on the cultural, political, and historical characteristics that shape vocational training. As a result, partners can develop innovative solutions that are not merely direct transfers of foreign practices but are well-informed by them, tailored to their local realities.

Finally, the research confirmed the assumption that intensive monitoring and participatory research also support the development of social dialogue and strengthen social partnership through the improvement in trust, cooperation, and mutual understanding. Billett et al. [

60] show that collaborative working among partners is a complex learning process. It entails building and maintaining shared purposes and goals, relations with partners, capacities for partnership work, partnership governance and leadership, and trust and trustworthiness. The Slovenian experience proves that the participation of partners in a monitoring and research process also has a significant impact on their cooperation, mutual understanding, and trust, making it a productive venue for designing common solutions.