A Hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger with a Subsurface Water Tank: Experimental Validation in a Hot–Arid Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

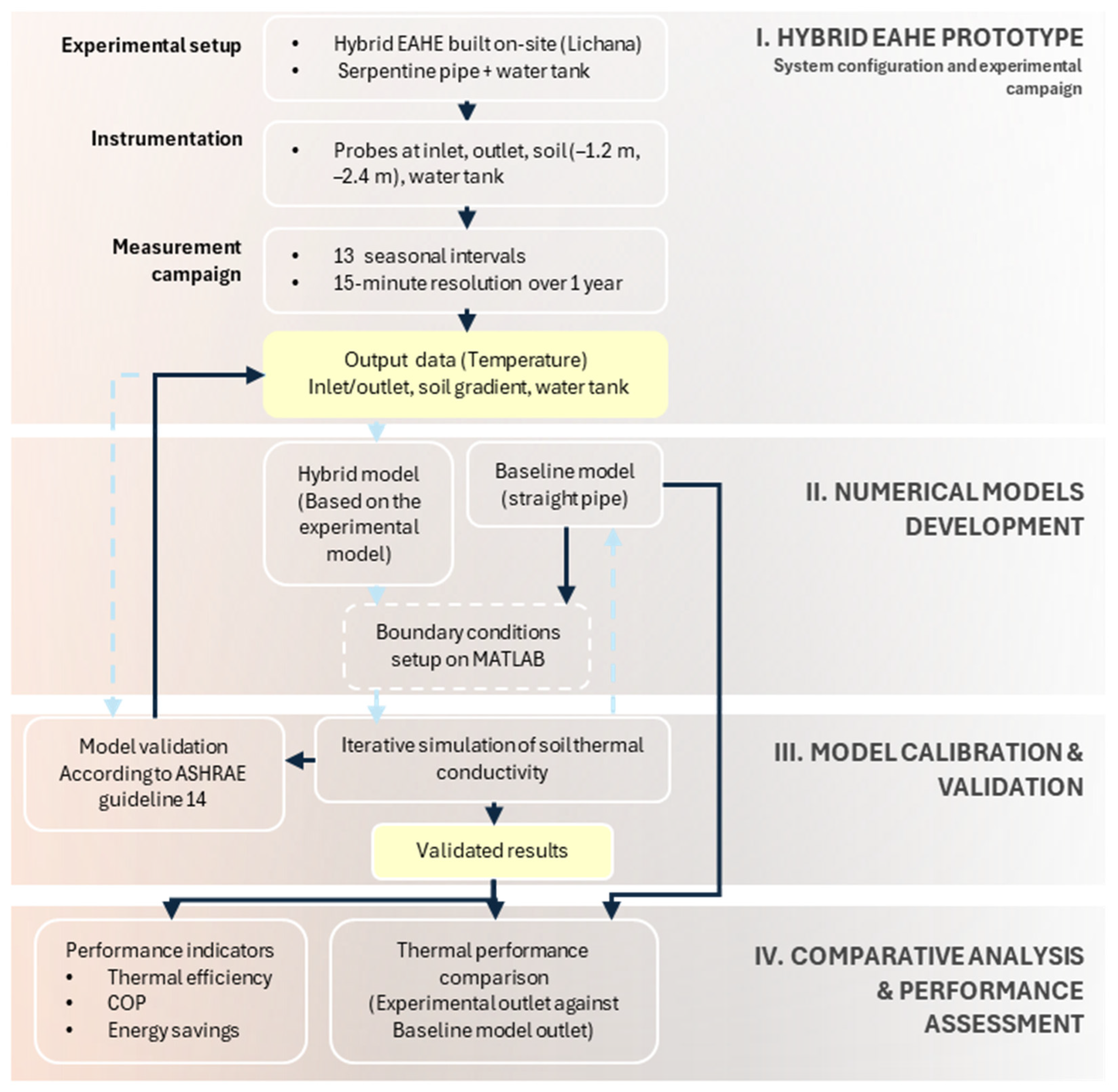

2. Methodology

- 1.

- Experimental setup: covers the on-site construction and monitoring of the serpentine EAHE system, integrated with a subsurface water tank. The system was tested under real boundary conditions representative of a hot arid climate, and the instrumentation protocol was designed to capture air and soil thermal responses over selected periods (Section 2.2).

- 2.

- Numerical model development involves the construction of two transient heat transfer models in MATLAB R2024b: one reproducing the experimental hybrid configuration and the other representing a simplified conventional baseline model EAHE used as a reference. Both models are designed to operate under identical climatic and geometric inputs (Section 3).

- 3.

- Model calibration and validation focus on tuning the numerical model parameters, primarily the soil thermal conductivity and initial temperature field, using a selected subset of the experimental data.

- 4.

- Comparative analysis and performance assessment apply the experimental hybrid device and the numerical baseline model to representative scenarios under the same operating conditions to quantify the impact of the tank integration and pipe layout on efficiency. For the performance assessment, thermal efficiency, Coefficient of Performance (COP), and energy-saving potential are addressed.

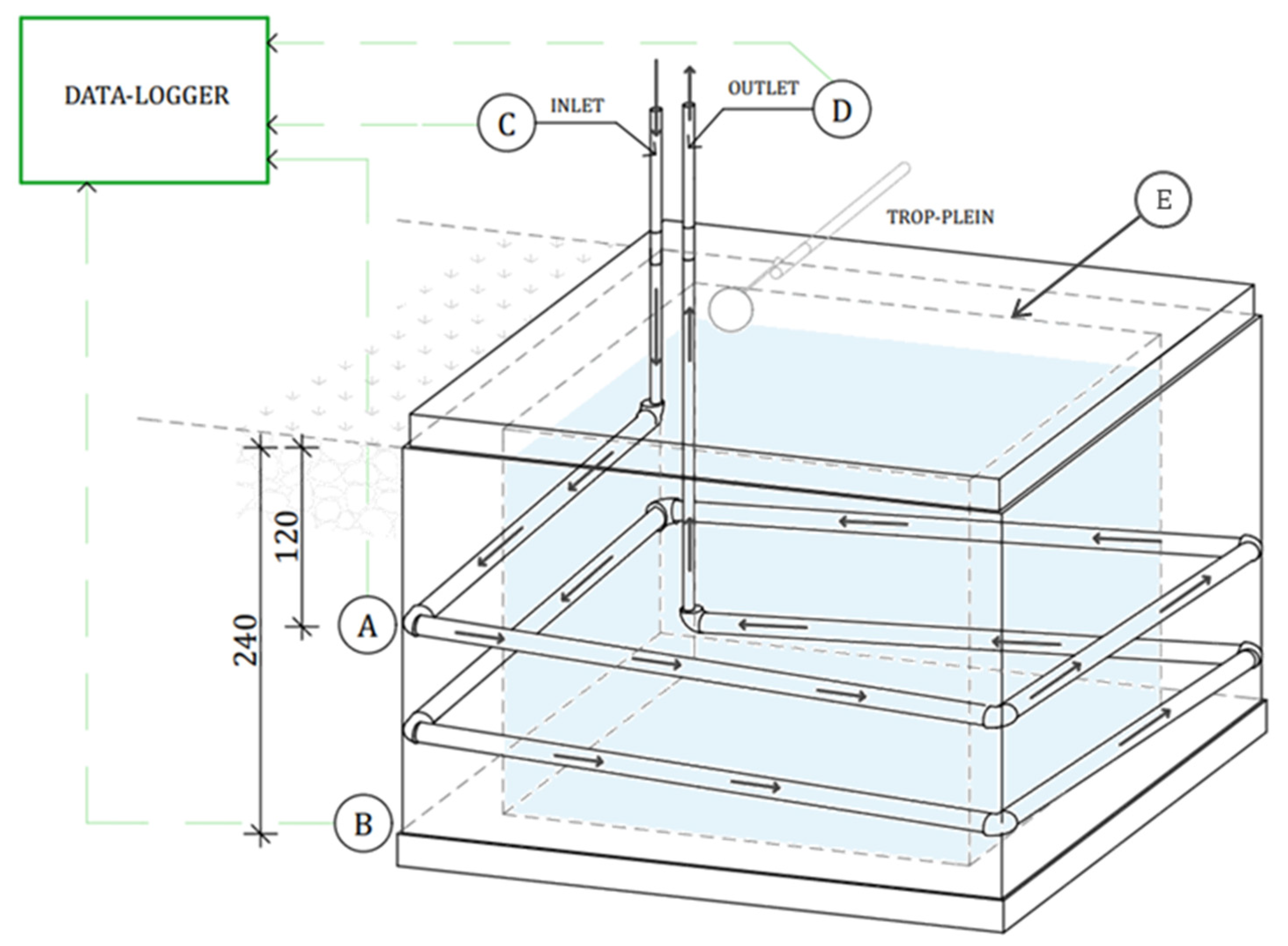

2.1. Experimental Setup and Data Acquisition

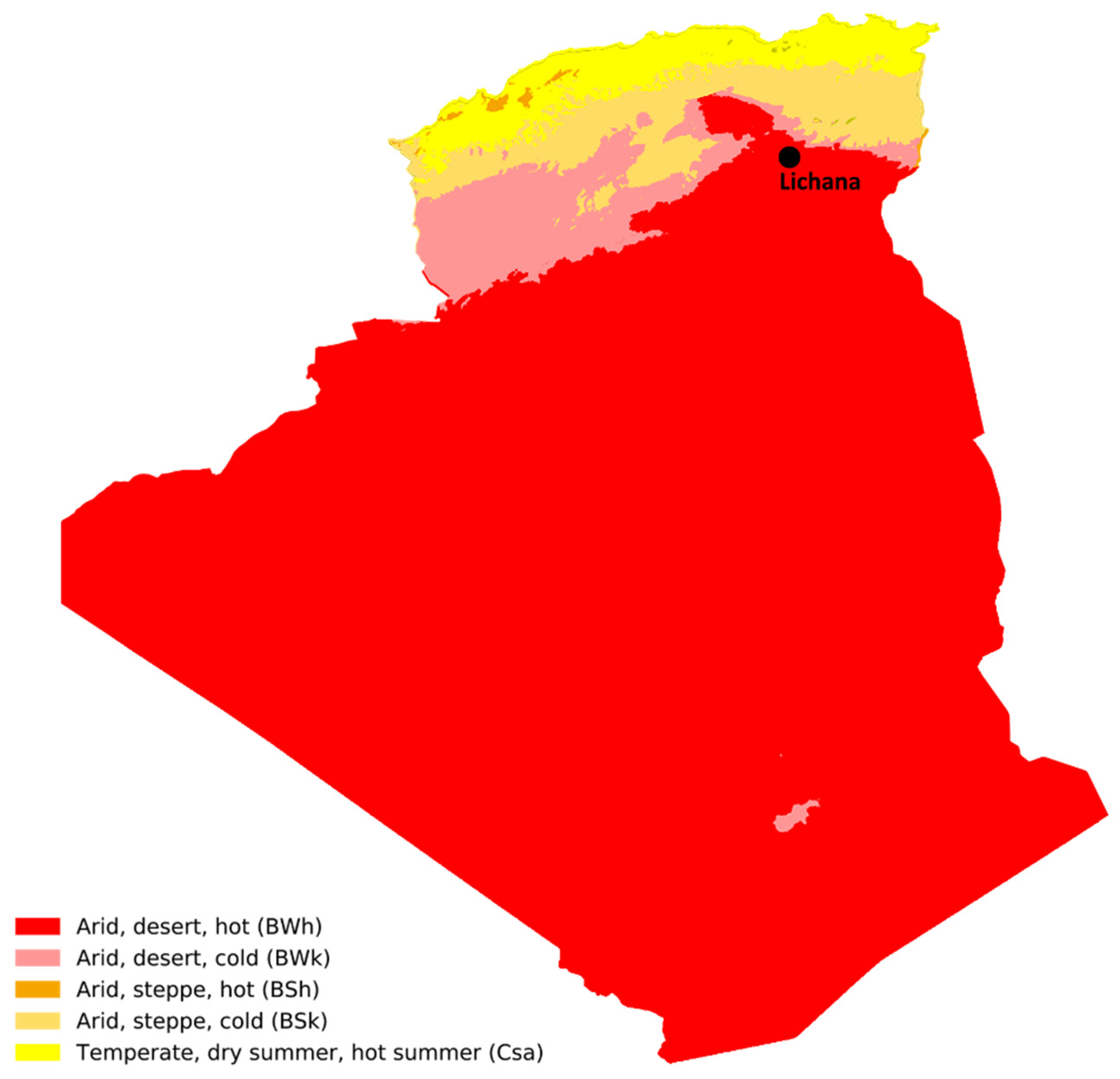

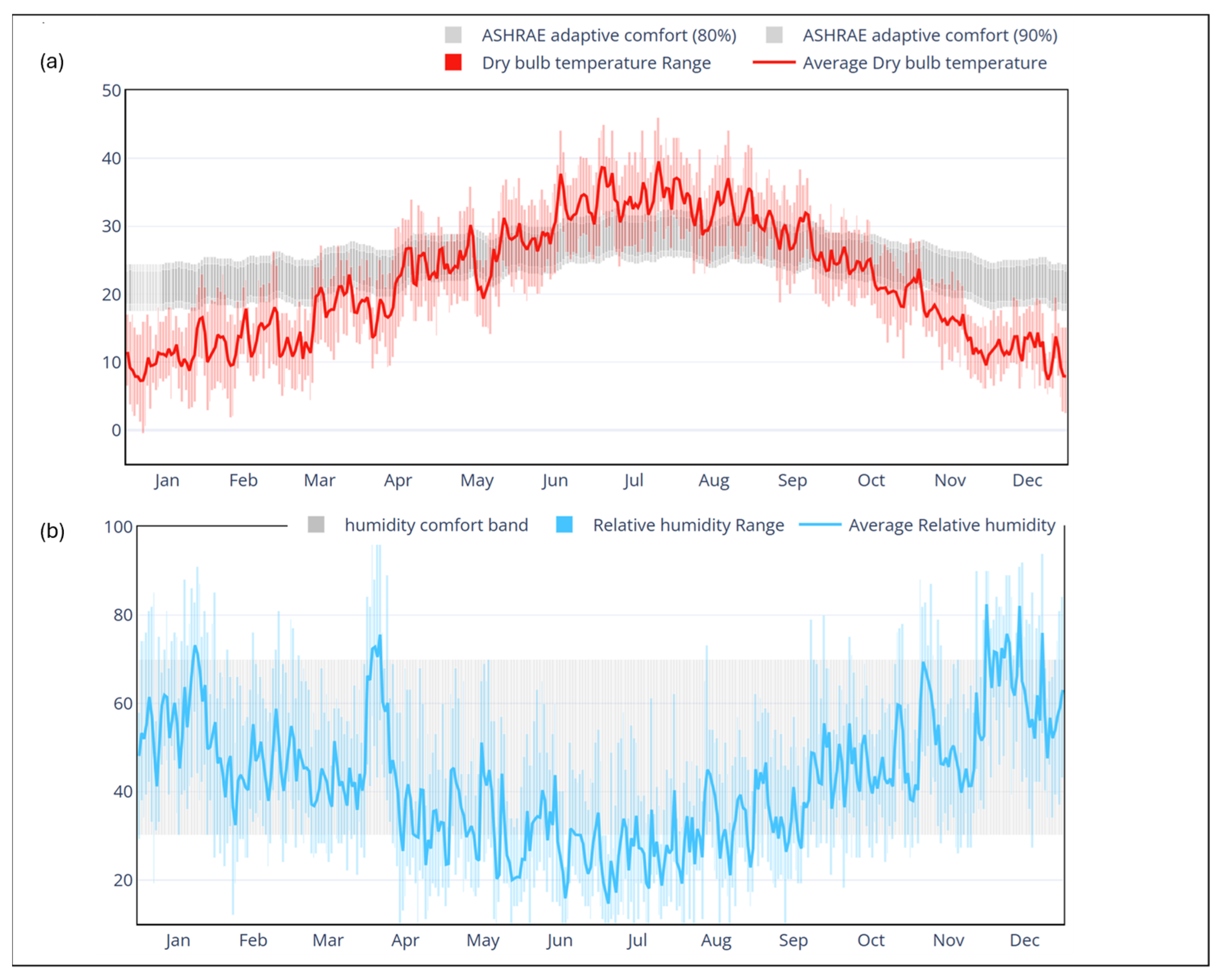

2.1.1. Site and Climate

2.1.2. System Configuration

2.2. Instrumentation and Monitoring Protocol

3. Numerical Model Development

- 1.

- A hybrid model for the EAHE (serpentine pipes + water tank) was developed, calibrated and validated, corresponding to the experimental setup and against its reported measured data,

- 2.

- A baseline model of an EAHE consisting of a straight buried pipe without a water tank, used for comparison against the hybrid model’s performance. In detail, in this model, the EAHE is represented by a straight, uniformly buried pipe of 27 m length at −2.4 m depth, operating under the same ambient and soil conditions as the hybrid system. Notably, the conventional baseline model omits the water tank integration; thus, the soil thermal resistance remains unchanged along the entire length of the pipe.

- The surrounding gypsum soil was thermally homogeneous and isotropic, with constant conductivity and diffusivity values. This is consistent with typical EAHE modeling practices and is supported by previous findings that soil thermal properties remain relatively stable over such time scales [24].

- Airflow inside the pipes was assumed to be fully developed and turbulent, allowing for a fixed convective heat transfer coefficient derived from Reynolds- and Nusselt-based correlations. Due to the ventilation system-controlled operation, transient fluctuations were neglected.

- Given its low thermal inertia and rapid equilibrium response, the thin PVC pipe wall was treated as conductive resistance with negligible thermal storage capacity.

- In the hybrid configuration, the buried water tank was modeled as a passive thermal mass. Its effect was represented by a stable boundary condition imposed on the adjacent soil, reflecting the tank’s high heat capacity and buffering role during the simulation period.

- is the air temperature at the pipe inlet.

- is the air temperature at the pipe after a length of pipe.

- is the undisturbed soil temperature far from the pipe (assumed constant over the segment).

- is the mass flow rate of air through the pipe.

- is the specific heat capacity of air.

- is the overall heat transfer coefficient between the air and the soil (W/m.K per unit length of pipe). It encompasses all the thermal resistances in series: convective resistance on the inner air side, conductive resistance of the pipe wall, and conductive resistance of the soil out to an effective far-field radius. In terms of thermal resistance. Therefore, is defined as follows:

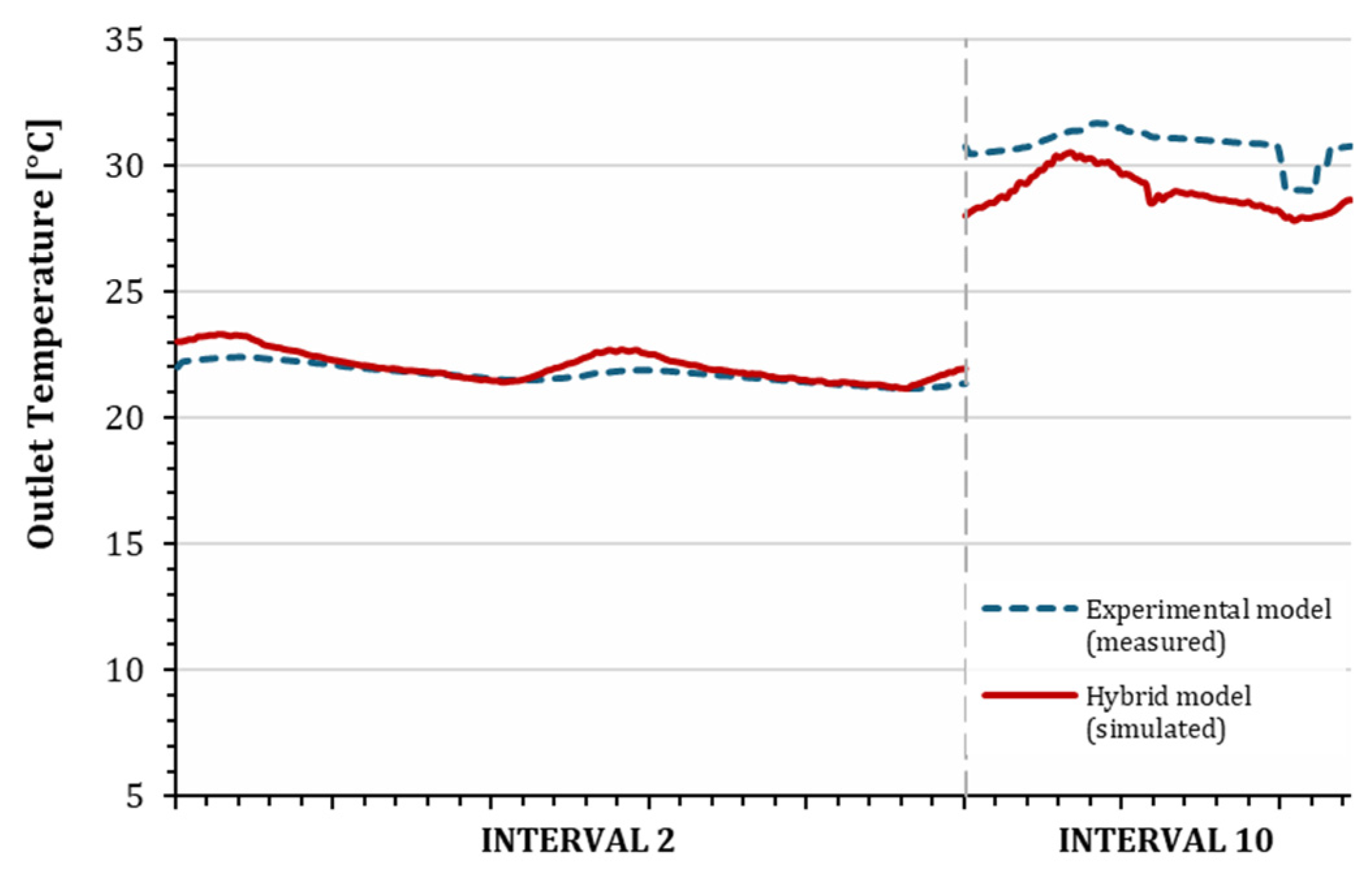

Hybrid EAHE Numerical Model Validation

- is the experimental temperature at time .

- is the simulated temperature at time .

- is the number of data points.

- Interval 2 (10–11 December 2023): winter heating operation, with average inlet air temperature of 11.6 °C and outlet temperature near 22.4 °C.

- Interval 10 (4–June 2024): peak summer cooling, with inlet air temperatures exceeding 45 °C and average outlet reduction exceeding 12 °C.

4. Results and Discussion

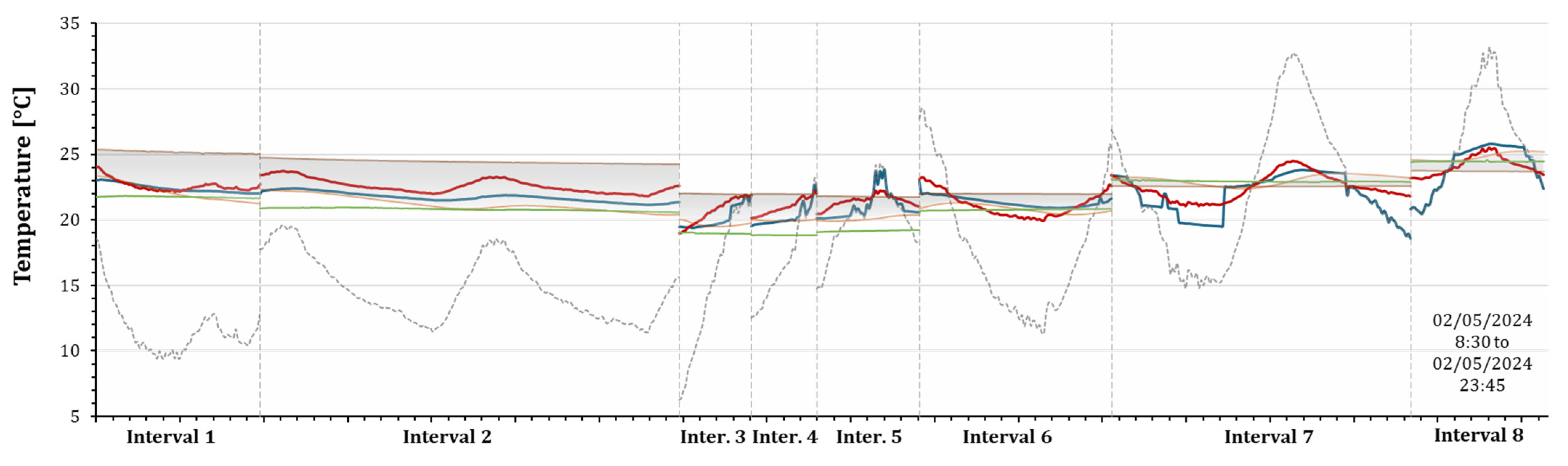

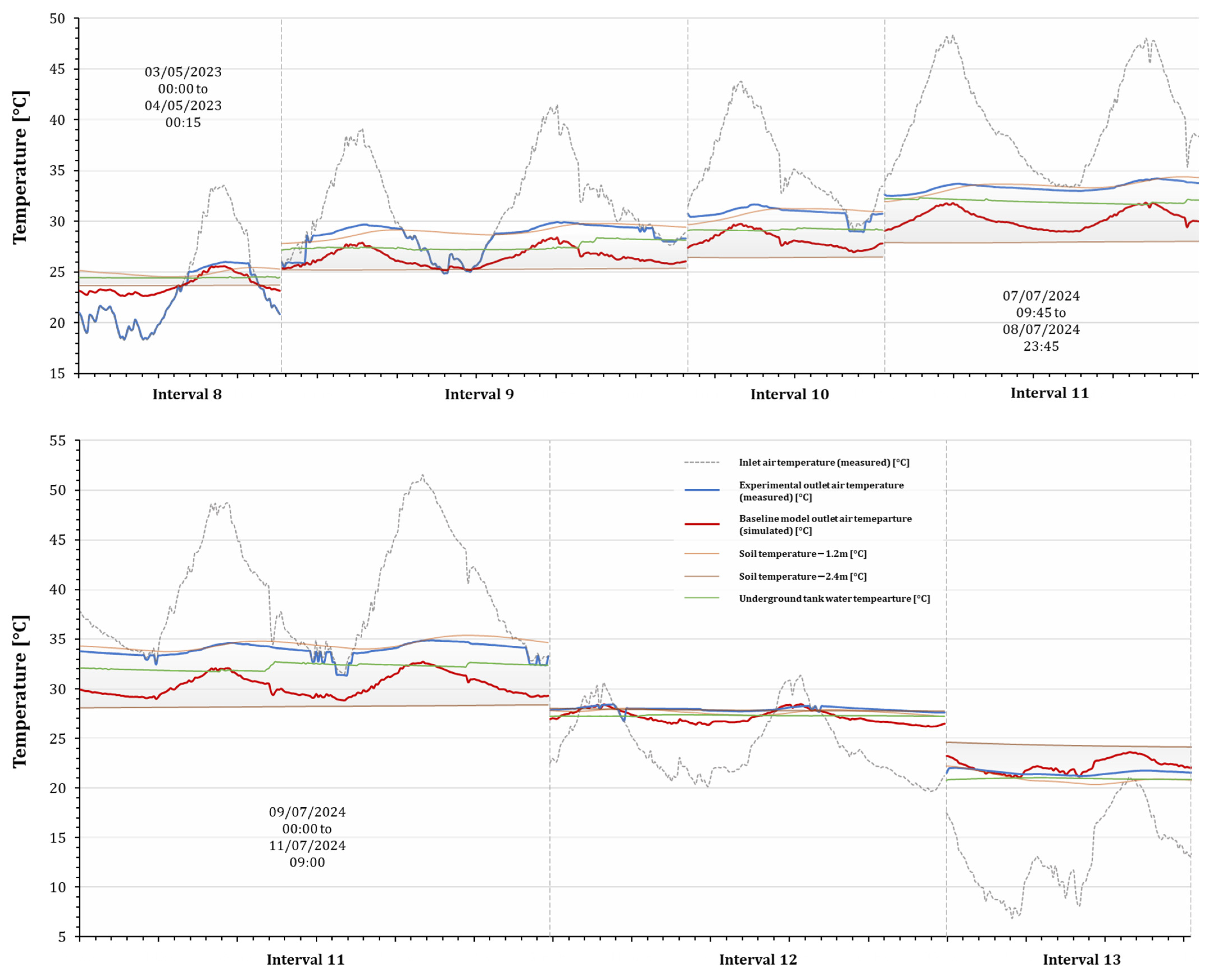

4.1. Thermal Performance Comparison

- Winter extremes (Interval 2: 10–11 December 2023). Baseline heating outperforms by ~0.8 °C, but both systems maintain outlet temperatures close to 22 °C from an inlet of ≈12 °C, demonstrating reliable heat gain in cold conditions.

- Moderate spring (Interval 8: 2–4 May 2024). The hybrid system slightly outperforms the baseline (ΔThybrid − ΔTbaseline ≈ +0.8 °C), indicating that the water tank’s thermal mass smooths soil–air exchange and enhances performance when inlet–soil gradients are moderate.

- Peak summer cooling (Interval 10: 17–18 June 2024). Baseline cooling exceeds hybrid by 2.6 °C (from inlet ≈ 42 °C to outlet ≈ 35 °C vs. 38 °C). While the baseline model thus attained a greater cooling magnitude, its outlet displayed larger daily swings linked to rapid soil-air heat transfer. The hybrid, buffered by the tank’s thermal inertia, produced a steadier outlet profile that tracked the ground temperature, offering moderate but more stable performance.

4.2. Performance Metrics and Energy Impact

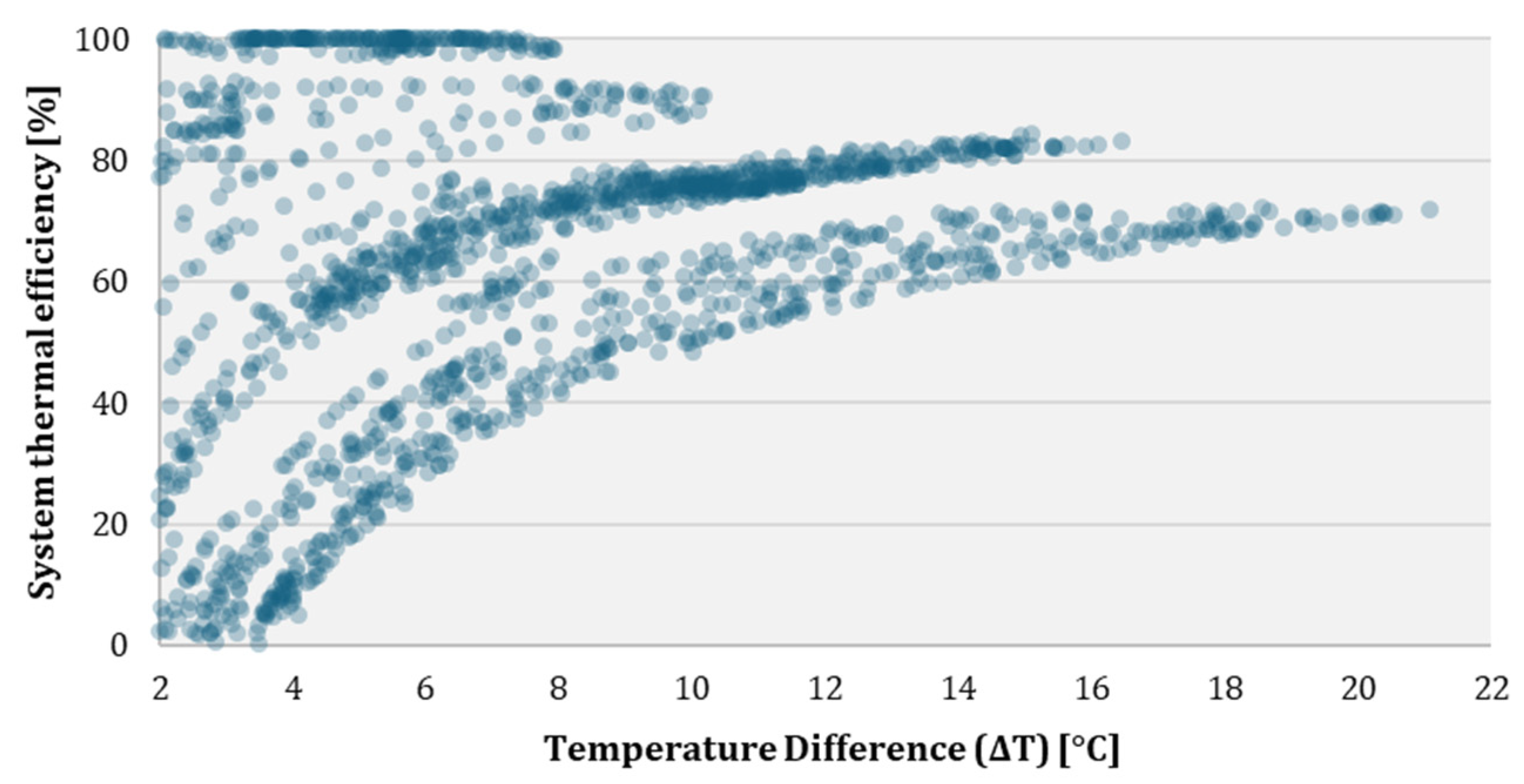

4.2.1. Thermal Efficiency

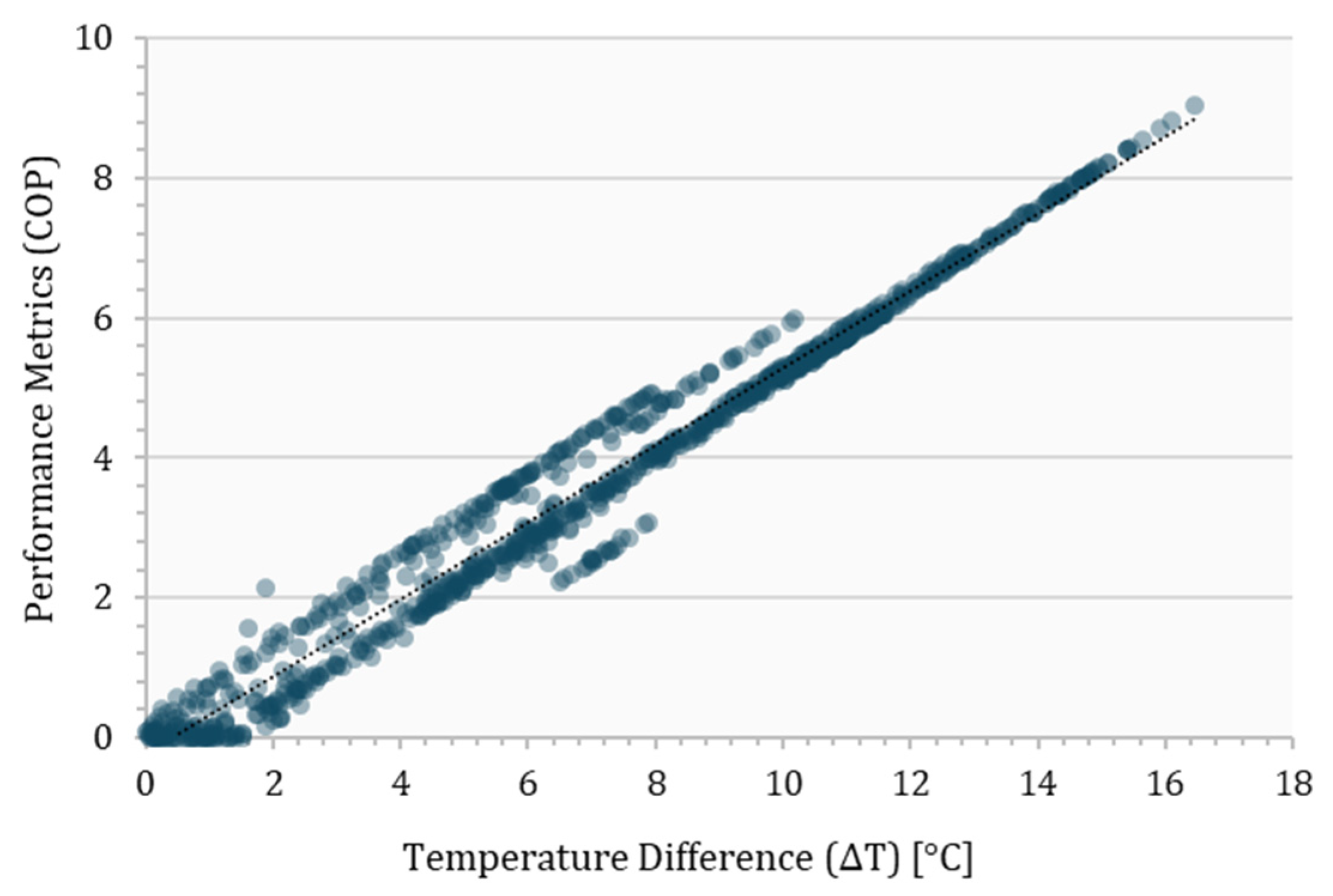

4.2.2. Coefficient of Performance (COP)

- Low-gradient regime (): In this zone, the COP values are highly scattered and fluctuate near zero. This behavior reflects a physically marginal heat exchange under such weak thermal gradients. The system performs minimal practical work and becomes highly sensitive to noise, particularly under real-world experimental variability.

- Moderate-gradient regime (): COP stabilizes within a functional operating band, mostly between 1.0 and 2.5, indicating that for every watt of electrical input, the system provides 1–2.5 W of thermal output. These values correspond predominantly to spring and autumn intervals, where moderate gradients enable steady, if not extreme, thermal recovery.

- High-gradient regime (): During peak heating and cooling episodes, the COP rises significantly, often exceeding 3.0 and reaching values up to 4.0. These high values align with periods when ambient conditions create strong contrasts with the subsurface thermal reservoir (water tank), typically in deep winter (Intervals 1–5, 13) and summer (Intervals 10–11).

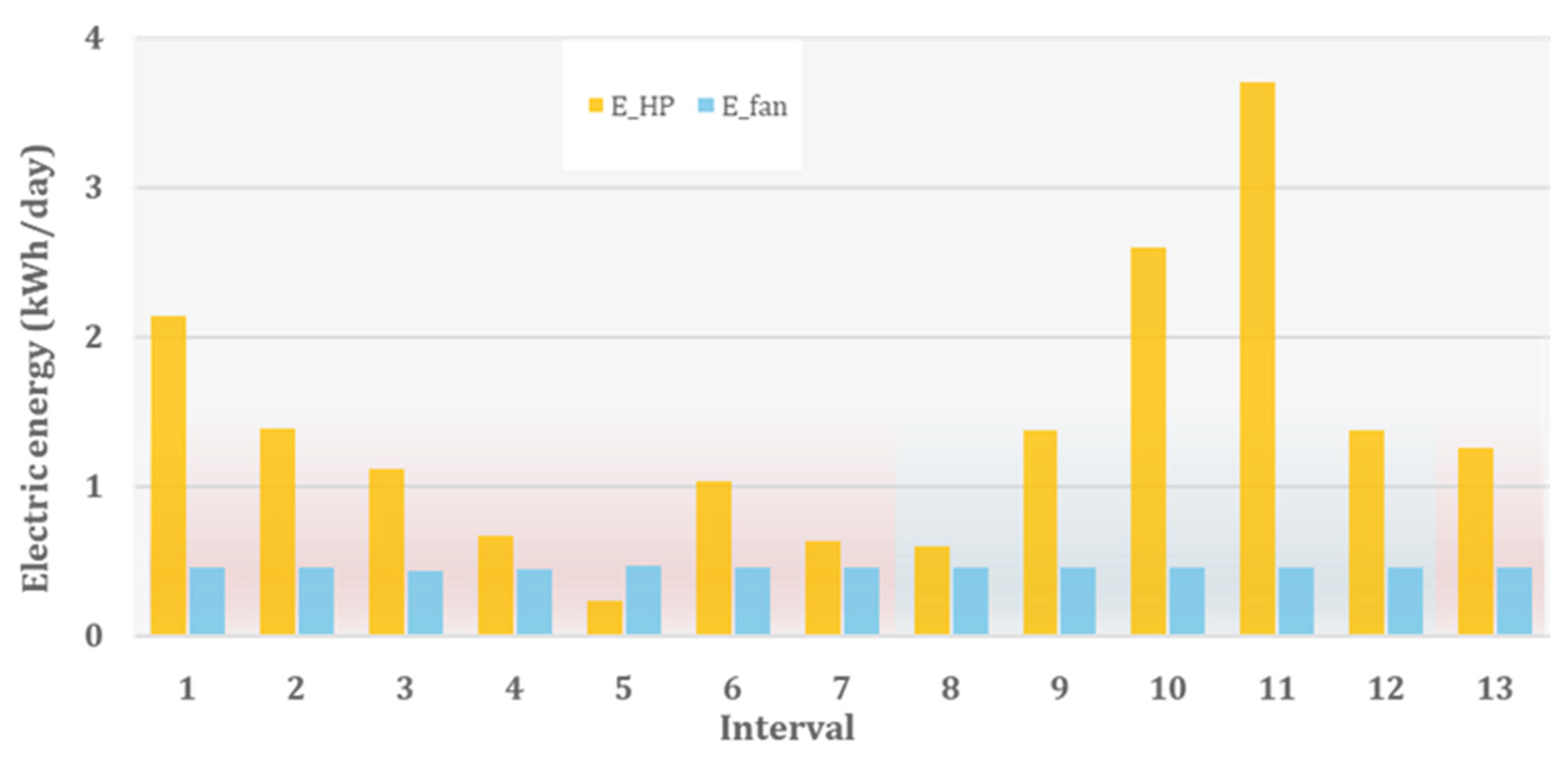

4.2.3. Energy Saving Potential

- The heat-pump electricity requirement EHP (kWh/day),

- The fan energy consumption Efan (kWh/day).

5. Conclusions

- Soil temperature data were limited to two depths in proximity to the water tank, which may not fully capture spatial thermal heterogeneity across the installation zone.

- The comparative baseline employs a single-depth straight pipe at −2.4 m, whereas the hybrid uses a depth-distributed serpentine (−1.2 to −2.4 m); the geometries are therefore not strictly equivalent. While results are normalized to the inlet–soil temperature difference (ΔT) and analyzed in season-specific intervals, depth selection can favor higher ΔT in the baseline.

- The baseline simulation model, although calibrated, is governed by simplified assumptions that do not incorporate transient soil thermal inertia or dynamic environmental coupling, potentially affecting short-term predictive accuracy.

- Experimental monitoring was conducted over a single climatic year, and while intervals were selected to reflect seasonal diversity, long-term performance consistency under atypical weather patterns remains unverified.

- Although incorporating subsurface water tanks aligns with widely adopted construction practices in Algeria and the hybrid configuration demonstrates measurable thermal stability benefits, its economic advantage over a conventional EAHE is not yet established. Accordingly, a dedicated life-cycle cost assessment, supported by multi-site validation across different soil types and climatic conditions, is required to verify scalability and confirm cost-effectiveness beyond thermal performance alone.

- The proposed configuration was tested on a single experimental rig, implying that broader generalizations across soil types, geographic locations, and design scales should be approached cautiously until further multi-site or parametric studies are conducted.

- In the numerical analysis, ambient air temperature was used as the inlet boundary condition. Coupling the EAHE to a specific building’s envelope and internal gains would require an integrated building energy model and is deferred to future studies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deroubaix, A.; Labuhn, I.; Camredon, M.; Gaubert, B.; Monerie, P.-A.; Popp, M.; Ramarohetra, J.; Ruprich-Robert, Y.; Silvers, L.G.; Siour, G. Large Uncertainties in Trends of Energy Demand for Heating and Cooling under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wei, H.; He, X.; Du, J.; Yang, D. Experimental Evaluation of an Earth–to–Air Heat Exchanger and Air Source Heat Pump Hybrid Indoor Air Conditioning System. Energy Build. 2021, 246, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Comprehensive Review on Climatic Feasibility and Economic Benefits of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 68, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi, N.; Sharma, A.; Nautiyal, H.; Goel, V. An Intense Review on the Latest Advancements of Earth Air Heat Exchangers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerdata. Algeria Energy Report 2022; Enerdata: Grenoble, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Algeria’s Energy Profile: Natural Gas and Electricity Consumption in 2024; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Albarghooth, A.; Ramiar, A.; Ramyar, R. Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger for Cooling Applications in a Hot and Dry Climate: Numerical and Experimental Study. Int. J. Eng. 2023, 36, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhri, N.; Benzaoui, A. Experimental Investigation of the Performance of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers in Arid Environments. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 180, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy and Mines. Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Development Plan (2015–2030); Ministry of Energy and Mines: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlikhani, F.; Goudarzi, H.; Solgi, E. Numerical Analysis of the Efficiency of Earth to Air Heat Exchange Systems in Cold and Hot-Arid Climates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 148, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Gang, W. Performance Evaluation of EAHE in Arid and Semi-Arid Climates Based on Parametric Simulation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darius, D.; Misaran, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Ismail, M.; Amaludin, A. Effects of Soil Moisture and Type on Thermal Performance of EAHE. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 226, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, N.; D’Agostino, D.; Vityi, A. Properties of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers (EAHE): Insights and Perspectives Based on System Performance. Energies 2025, 18, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshlak, H. A Review of Earth-Air Heat Exchangers: From Fundamental Principles to Hybrid Systems with Renewable Energy Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, D.M.N.; Aljubury, I.M.A.; Al Maimuri, N.M.L.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Rashid, F.L.; Ameen, A.; Dong, S.; Mukhtar, Y. Experimental Evaluation of a Hybrid Evaporative and Groundwater Cooling System for Enhancing Photovoltaic Efficiency in Arid Climates. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, S.; Shahrestani, M.I.; Sayadian, S.; Maerefat, M.; Poshtiri, A.H. Performance Analysis of an Integrated Cooling System Consisted of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) and Water Spray Channel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 143, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaama, M.H.; Menhoudj, S.; Mokhtari, A.M.; Lachi, M. Comparative Study of the Thermal Performance of an Earth Air Heat Exchanger and Seasonal Storage Systems: Experimental Validation of Artificial Neural Networks Model. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, N.; Rosa, N.; Monteiro, H.; Costa, J.J. Advances in Standalone and Hybrid Earth-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) Systems for Buildings: A Review. Energy Build. 2021, 240, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; Tartarini, F.; Nguyen, C.; Schiavon, S. CBE Clima Tool: A Free and Open-Source Web Application for Climate Analysis Tailored to Sustainable Building Design. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajmi, F.; Loveday, D.L.; Hanby, V.I. The Cooling Potential of Earth–Air Heat Exchangers for Domestic Buildings in a Desert Climate. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, S.; Mahboub, C.; Moummi, A. Numerical Approach to Predict the Outlet Temperature of Earth-to-Air-Heat-Exchanger. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 21, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, S. Parametric Study of Air/Soil Heat Exchanger Destined for Cooling/Heating the Local in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, University Mohamed Khider of Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdid, C.-E.; Benchabane, A.; Rouag, A.; Moummi, N.; Melhegueg, M.-A.; Moummi, A.; Benabdi, M.-L.; Brima, A. Thermal Design of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger. Part II: A New Transient Semi-Analytical Model and Experimental Validation for Estimating Air Temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Guideline 14-2014; Measurement of Energy, Demand, and Water Savings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ounis, S.; Aste, N.; Butera, F.M.; Del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Adhikari, R.S. Optimal Balance between Heating, Cooling and Environmental Impacts: A Method for Appropriate Assessment of Building Envelope’s U-Value. Energies 2022, 15, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervals | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | 7 December 2023 17:05 | 14 December 2023 11:40 | 1 February 2024 07:50 | 3 February 2024 07:50 | 16 February 2024 08:05 | 14 March 2024 14:45 | 28 March 2024 18:40 | 2 May 2024 08:30 | 30 May 2024 08:30 | 17 June 2024 10:23 | 7 July 2024 09:45 | 31 October 2024 09:00 | 18 December 2024 16:55 |

| End | 8 December 2023 11:50 | 16 December 2023 11:40 | 1 February 2024 16:05 | 3 February 2024 15:20 | 16 February 2024 19:50 | 15 March 2024 12:45 | 30 March 2024 04:55 | 4 May 2024 00:15 | 1 June 2024 09:15 | 18 June 2024 09:53 | 11 July 2024 09:00 | 2 November 2024 09:00 | 21 December 2024 17:10 |

| Inlet Mean Temperature [°C] | 11.64 | 14.72 | 15.21 | 16.92 | 19.95 | 17.71 | 22.18 | 24.69 | 31.35 | 35.37 | 39.73 | 24.31 | 14.67 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Inlet air temperature [°C] | As measured |

| Soil temperatures at −1.2 m and −2.4 m | As measured |

| Inlet air velocity (u) | 2.5 m/s |

| Pipe inner diameter (Din) | 0.110 m |

| Pipe outer diameter (Dout) | 0.115 m + wall thickness |

| Pipe length (L) | 27 m |

| Soil thermal conductivity (λsoil) | 0.52 W/m.K (0.54 calibrated) |

| Pipe thermal conductivity (λpipe) | 0.17 W/m.K |

| Air density (ρair) | 1.127 kg/m3 |

| Air specific heat capacity (cp,air) | 1006 J/kg.K |

| Air thermal conductivity (λsair) | 0.026 W/m.K |

| Dynamic viscosity of air (μ) | 1.85 × 10−5 kg/m·s |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| MBE (%) < 10% | 3.66 |

| CVRMSE (%) < 30% | 5.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ounis, S.; Boucherit, O.; Moummi, A.; Bouzir, T.A.K.; Berkouk, D.; Leonforte, F.; Pero, C.D.; Gomaa, M.M. A Hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger with a Subsurface Water Tank: Experimental Validation in a Hot–Arid Climate. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210216

Ounis S, Boucherit O, Moummi A, Bouzir TAK, Berkouk D, Leonforte F, Pero CD, Gomaa MM. A Hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger with a Subsurface Water Tank: Experimental Validation in a Hot–Arid Climate. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210216

Chicago/Turabian StyleOunis, Safieddine, Okba Boucherit, Abdelhafid Moummi, Tallal Abdel Karim Bouzir, Djihed Berkouk, Fabrizio Leonforte, Claudio Del Pero, and Mohammed M. Gomaa. 2025. "A Hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger with a Subsurface Water Tank: Experimental Validation in a Hot–Arid Climate" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210216

APA StyleOunis, S., Boucherit, O., Moummi, A., Bouzir, T. A. K., Berkouk, D., Leonforte, F., Pero, C. D., & Gomaa, M. M. (2025). A Hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger with a Subsurface Water Tank: Experimental Validation in a Hot–Arid Climate. Sustainability, 17(22), 10216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210216