Building Climate Adaptation Capacity: A Pedagogical Model for Training Civil Engineers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Adaptation to Climate Change for Civil Engineers

3. Pedagogical Models in Civil Engineering Education

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

- A collaborative online workshop: Hosted by the research team (see workshop agenda in Appendix A), this consisted of structured breakout groups (60–75 min each over two days, in English). The workshop focused on climate adaptation training in the civil engineering sector and included semi-structured dialogues exploring best practices and success measures. A total of 21 participants attended the workshops and their profiles are listed in Table 1. For clarity, these attendees are referred to as “participants.” While there was no formal mechanism for one-on-one interviews within the workshop, several smaller breakout rooms allowed for deeper engagement in semi-private groupings.

- Follow-up semi-structured interviews: Conducted the following year with two selected participants (P20 and P21) from the original workshop group. These interviews lasted approximately 20 min each and were designed to capture evolving perspectives, implementation challenges, and suggestions for training design. These are referred to as “interviewees”. These interview responses were synthesized with the workshop data during thematic analysis and are presented alongside the broader participant insights for coherence and depth.

- Peer review by members of the research team, who have expertise in engineering education, adaptation planning, and qualitative research.

- Pilot testing with two external colleagues in engineering and climate policy, leading to minor revisions to improve question flow and clarity.

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Awareness and Engagement

If there is a stage of knowledge that’s known to the average person but that’s not reflected in the codes and standards, then you still must operate in the codes and standards…sometimes it’s not about the carrot (costs/benefits) it’s about a stick (regulations).

We are always treating climate change as an add-on, how do we get this no longer to be an add-on and something that we usually do, standards is a way to do that.

I think that by putting stricter rules in place, I think that it’s one of the only ways to change practices in general because otherwise everyone will always just have the minimum costs as their goal.

Use continuing education credits approved by professional regulators which could mandate engineers to take the training courses.

We should implement a national exchange central entity responsible to encourage end enable climate change adaptation training.

The trainers need to understand what they are teaching, they should be local and authentic. Who delivers the training really matters, ideally someone from the community.

5.2. Reflective Practice

Training for engineers is different than for other professions and needs to be more technical.

…you know how to try to find the information to really tailor the activity to the group you want, separate the activities by profession.

Civil engineers need to be more open minded and open to solutions outside the traditional way of doing things is… we need to move past that and start coming up with different solutions that will sustain us into the future.

5.3. Project-Based Learning

Training needs to bear in mind the regional realities, how adaptation in approaches and solutions can be put into place. Climate change is global but it’s felt locally and needs to be adapted locally.

We actually had an in-person activity on-site which was incredible. I think it has more power to change people’s perception, but other than that… as much as possible it’s the case studies on the ground, it’s really something that is powerful, along with the person who did the project who could explain and then answer questions and ideally this person is an engineer… in any case, the person who really led the project and who knows the most things about it.

5.4. Design Thinking

I think the best tool would be to have more diverse teams with perhaps a few more generalists. You know, you can be an expert in one field but also a generalist or open to other expertise and also other professions, such as ecologists, biologists, development planners and all that.

We are currently working on simplifying an assessment tool that should be more user friendly for small communities, allowing the process to be completed in a number of weeks instead of months.

They want to be able to implement things, people love to see case studies, opportunities for discussion, bring training on site, or go to a site with a camera, play a video with a live presenter if a site visit is not possible.

6. Model Development, Structure and Application

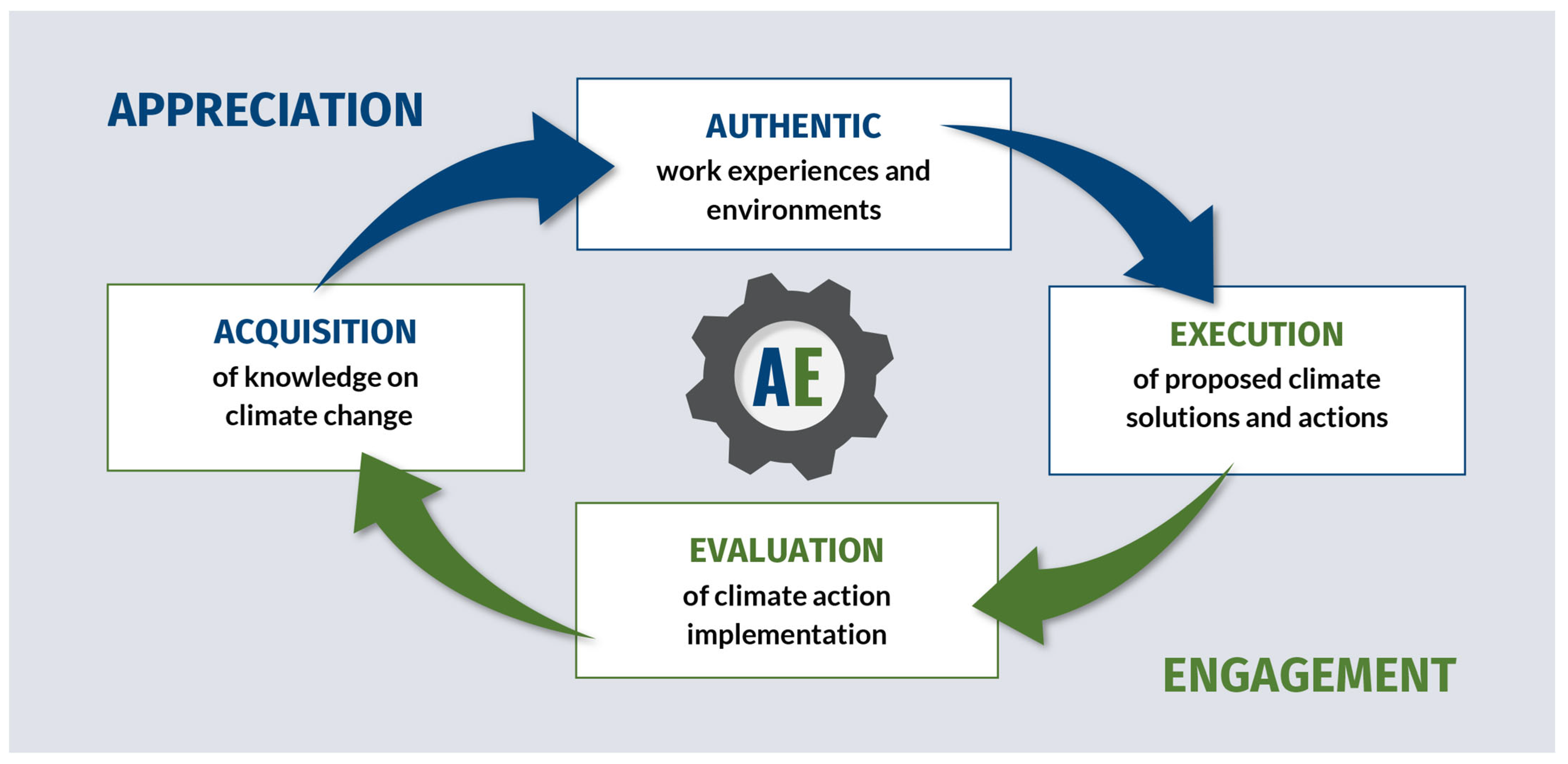

- Acquisition—Appreciation (Climate Awareness): foundational literacy and motivational framing.

- Authenticity—Project-Based Learning: application in real contexts and localized decision-making.

- Execution—Design Thinking: iterative and collaborative problem-solving focused on adaptation solutions.

- Evaluation—Reflective Practice: structured reflection on performance and learning to reinforce long-term engagement.

6.1. Stages of the AAEE Model

- Acquisition (Appreciation/Climate Awareness)This stage builds foundational understanding of climate risks, relevance to engineering practice, and potential professional impacts. Delivery formats may include webinars, online modules, or foundational briefings tailored to local asset lifecycles or regulatory contexts.

- Authentic (Project-Based Learning)This stage emphasizes situating learning in real-world or place-based practice. Participants engage in case studies or field-based activities involving their own assets, challenges, or design environments to connect theory to context.

- Execution (Design Thinking)Applying design thinking, this stage encourages co-creation of solutions through collaborative workshops or challenge-based scenarios (e.g., the multiplication of urban heat islands during extreme heat waves or the redesign of stormwater infrastructure under future climate projections).

- Evaluation (Reflective Practice)Structured reflection helps embed adaptive thinking and learning. Reflective journaling, peer discussions, follow-up assessments, or post-project debriefs support learners in internalizing lessons and planning future change.

6.2. Tools to Support Training Design and Delivery

- Table 3—Overview of recommended practices aligned with the AAEE Model.

- Table 4—Checklist that guides instructional designers in ensuring all four stages are represented within a training session or course outline.

- Table 5 —Detailed guidance for the Acquisition (Appreciation/Climate Awareness) stage, including pedagogical intent, delivery formats, and an applied example.

- Table 6 —Detailed guidance for the Execution (Engagement/Design Thinking) stage, including practice-based workflows and evaluation tools.

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Workshop Interview Agenda

- Agenda

- Engineers in a Changing Climate

- Engineering Collaborative Workshop

- RCERA-BRACE (hosted by Université de Moncton)

- March 22nd (1:00 p.m.–4 p.m. EDT)

- 1:00 p.m.–1:15 p.m. Welcome remarks

- 1:15 p.m.–1:45 p.m. BRACE Project Exchange

- 1:45 p.m.–2:30 p.m. Perfectly Adapting (breakout rooms)

- What are the essential elements of adaptation training for engineers?

- 2:30 p.m.–2:45 p.m. Break

- 2:45 p.m.–3:50 p.m. Knowledge exchange

- How to promote knowledge exchange in the engineering sector?

- 3:50 p.m.–4:00 p.m. Wrap-up

- March 23rd (1:00 p.m.–4 p.m. EDT)

- 1:00 p.m.–1:15 p.m. Day 1 review

- 1:15 p.m.–2:30 p.m. Measuring success

- How to measure the success of adaptation training?

- 2:30 p.m.–2:45 p.m. Break

- 2:45 p.m.–3:30 p.m. Engineering adaptation pathway (breakout rooms)

- What key components should be included?

- 3:30 p.m.–3:50 p.m. Next steps

- 3:50 p.m.–4:00 p.m. Conclusion and acknowledgements

Appendix B. Semi-Structured Workshop Interview Guide (During the Workshop)

- Climate change adaptation

- How do you feel about climate change?

- Tell me about the role of the engineer in the fight for climate change.

- How can engineers consider climate change in their work?

- What kind of knowledge should engineers need in regard to climate change?

- What skills should engineers need to take into consideration the effects of climate change?

- Training format

- Tell me about your experience (as a trainer, organizer or participant) with engineering professional learning.

- What do professional learning activities usually look like in engineering?

- How to ensure a proper delivery of educational content on a professional learning activity?

- Describe the optimal format for a professional learning activity in engineering.

- ○

- What is the optimal duration of a professional learning activity?

- ○

- What do you think of online training?

- ○

- How to measure and evaluate the delivery of educational content of a professional learning activity?

- ○

- How to measure and evaluate the effects of training?

- Best practices and challenges in engineering professional learning

- Tell me about your experiences with professional learning activities in the field of climate change.

- What should engineering professional learning activities about climate change look like?

- ○

- What are the best practices in the type of training?

- ▪

- How do you explain that these practices are «best»?

- ○

- What are the challenges in this type of training?

- ▪

- How do you explain the appearance of these challenges?

- Do you have any suggestions for climate change professional learning activities targeted towards engineers?

Appendix C. Semi-Structured Interview Guide (One Year After the Workshop)

- What role do you have in adaptation training?

- Do you find your perspective has changed since you took on this role?

- What should the main message be to engineers about adaptation and climate change?

- What are the principal skills that engineers need to be able to apply adaptation in their work?

- What were the types of training that you were offering to engineers on your project?

- What are some successes that came out of your project?

- What about some of the challenges in training engineers? Have you found that there were challenges along the way?

- How do you measure the success of your training or what to change for the future?

- How do you get the engineers to apply what they have learned in their practice, or have you thought about that side of things?

- If you had an unlimited budget and all the time in the world to create training for engineers, what would that look like?

- Do you have any suggestions for future training of different activities that you would have liked to try out if you had more time?

Appendix D. Pedagogical Tools Supporting the Appreciation and Engagement Model

Appendix D.1. Summary of Recommended Practices

Appendix D.2. Practice Descriptions and Case Study Example

- Table 5 focuses on the Appreciation side of the model (Acquisition + Authenticity)

- Table 6 focuses on the Engagement side of the model (Execution + Evaluation)

- A concise definition of the practice

- Guidance on how to implement it

- A case study example to illustrate potential application

References

- Anderson, A. Climate Change Education for Mitigation and Adaptation. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, N. Civil Engineers’ Role in Saving the World: Updating the Moral Basis of the Profession. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 2021, 174, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, R.; Clark, D.; Bourque, J.; Coffman, D.; Beugin, D. Submergés: Les Coûts des Changements Climatiques Pour les Infrastructures au Canada; Institut Canadien pour des Choix Climatiques: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). United in Science 2021: A Multi-Organization High-Level Compilation of the Latest Climate Science Information; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, F.J.; Lulham, N. Canada in a Changing Climate: National Issues Report; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, S.; Arnold, S. Provinces de l’Atlantique. In Le Canada Dans un Climat en Changement: Le Rapport sur les Perspectives Régionales; Warren, F.J., Lulham, N., Lemmen, D.S., Eds.; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eyquem, J. Mers Montantes et Sables Mouvants: Allier les Infrastructures Naturelles et Grises Pour Protéger les Collectivités des Côtes et Ouest du Canada; Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2021: The Heat is on–A World of Climate Promises Not Yet Delivered; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Spreading Like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Wiek, A.; Keeler, L.; Redman, C. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key Competencies in Sustainability in Higher Education—Toward an Agreed-Upon Reference Framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K.; Rieckmann, M.; Barth, M. Seeking Sustainability Competence and Capability in the ESD and HESD Literature: An International Philosophical Hermeneutic Analysis. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop; UNESCO-UNEVOC. Meeting Skill Needs for the Green Transition: Skills Anticipation and VET for a Greener Future. In Cedefop Practical Guide 4; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassani, F.; Saleem, M.R.; Messner, J. Integrating Sustainability in Engineering: A Global Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy: Building Resilient Communities and a Strong Economy; Government of Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bramald, T.M.; Heidrich, O.; Hall, J.A. Teaching Sustainability to First-Year Civil Engineering Students. Eng. Sustain. 2015, 168, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canney, N.; Bielefeldt, A. A Framework for the Development of Social Responsibility in Engineers. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 31, 414–424. [Google Scholar]

- Chance, S.; Lawlor, R.; Direito, I.; Mitchell, J. Above and Beyond: Ethics and Responsibility in Civil Engineering. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 26, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineers Canada. Public Guideline: Principles of Climate Adaptation and Mitigation for Engineers; Engineers Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, B.; Leduc, R.; Savard, L. Sustainable Development in Engineering: A Review of Principles and Definition of a Conceptual Framework. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2009, 26, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Deng, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, T.; Deng, S.; Zhao, Z. Teaching Sustainability Principles to Engineering Educators. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 37, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Jowitt, P.W. Sustainability and the Formation of the Civil Engineer. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2004, 157, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, L.; Chang, R.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Coddington, A.; Daniel, S.; Cook, E.; Crossin, E.; Cosson, B.; Turner, J.; Mazzurco, A.; et al. From Problem-Based Learning to Practice-Based Education: A Framework for Shaping Future Engineers. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 46, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Cooper Ordoñez, R.E.; Silva, D.; Quelhas, O.I.G.; Leal Filho, W.; Santa-Eulália, L.A. An Analysis of the Difficulties Associated to Sustainability Insertion in Engineering Education: Examples from HEIs in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.; Rooney, D.; Gardner, A.; Willey, K.; Boud, D.; Fitzgerald, T. Engineers’ Professional Learning: A Practice-Theory Perspective. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 40, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, F.J.; Lemmen, D.S. Canada in a Changing Climate: Sector Perspectives on Impacts and Adaptation; Natural Resources Canada, Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, N.; Norton, E. Educating Civil Engineers for the Twenty-First Century: The ‘New-Model Engineer’. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 2023, 177, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, J.; Ferranti, E. Infrastructure Resilience under a Changing Climate: The Urgent Need for Engineers to Act. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 2024, 177, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineers Canada. Climate Change and Infrastructure Risk Training for Engineering Professionals. 2024. Available online: https://engineerscanada.ca/news-and-events/news/climate-change-and-infrastructure-risk-training-for-engineering-professionals (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Engineers Canada. Principes D’adaptation aux Changements Climatiques à L’intention des Ingénieurs; Bureau Canadien des Conditions d’Admission en Génie, Engineers Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, F. More than Technical Experts: Engineering Professionals’ Perspectives on the Role of Soft Skills in Their Practice. Ind. High. Educ. 2021, 36, 095042222110347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environics Research. Building Capacity to Accelerate Climate Change Adaptation Action in Canada; Environics Research: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Building Regional Adaptation Capacity and Expertise Program; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/climate-change/building-regional-adaptation-capacity-and-expertise-program/21324 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Kolmos, A.; Hadgraft, R.G.; Holgaard, J.E. Response Strategies for Curriculum Change in Engineering. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2015, 26, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. Teaching and Learning STEM: A Practical Guide; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sundman, J.; Feng, X.; Shrestha, A.; Johri, A.; Varis, O.; Taka, M. Experiential learning for sustainability: A systematic review and research agenda for engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2025, 50, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The Integration of Competences for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: An Analysis of Bachelor Programs in Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. Le Praticien réflexif: À la Recherche du Savoir Caché Dans L’agir Professionnel; Heynemand, J.; Gagnon, D., Translators; Les Éditions Logiques: Montréal, QC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Huang, Z.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Ren, K. Individual sustainability competence development in engineering education: Community interaction open-source learning. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J.; IDEO. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2009, 7, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Lynham, S.A.; Guba, E.G. Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences, Revisited. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 108–151. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M.A. A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M. Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2020, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mucchielli, A. L’analyse Qualitative en Sciences Humaines et Sociales; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, C.; Allard, R. La pédagogie de la conscientisation et de l’engagement: Pour une éducation à la citoyenneté démocratique dans une perspective planétaire. Éduc. Francophonie 2002, 30, 66–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marleau, M.-È. Les Processus de Prise de Conscience et D’action Environnementales: Le cas d’un Groupe D’enseignants en Formation en Éducation Relative à L’environnement. Ph.D. Thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, M. La pédagogie en milieu minoritaire francophone: Une recension des écrits. Inst. Can. Rech. Minor. Linguist. 2005. Available online: https://icrml.ca/fr/recherches-et-publications/publications-de-l-icrml/download/125/8422/47?method=view (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Goyette, N.; Martineau, S. Les Défis de la Formation Initiale des Enseignants et le Développement d’une Identité Professionnelle Favorisant le Bien-Être. Phronesis 2019, 7, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kolmos, A.; Du, X. Forms of Implementation and Challenges of PBL in Engineering Education: A Review of Literature. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 46, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruneau, D.; El Jai, B.; Dionne, L.; Louis, N.; Potvin, P. Pensée Design pour le Développement Durable: Applications de la Démarche en Milieux Scolaire, Académique et Communautaire. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 24, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, T.; O’Reilly, J. Theory, Practice and Interiority: An Extended Epistemology for Engineering Education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 45, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifler, O.; Dahlin, J.-E. Curriculum Integration of Sustainability in Engineering Education—A National Study of Programme Director Perspectives. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S.; Holton, E.F.; Swanson, R.A. The Adult Learner. The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 8th ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Participant ID | Province | Sector | Role | Academic Background | Years Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Ontario | Federal Government | BRACE Coordinator | Project Management | 25+ |

| P2 | Quebec | Federal Government | Climate Agency | Service Delivery | 15+ |

| P3 | British Columbia | Federal Government | Climate Agency | PhD. Climate | 20 |

| P4 | Ontario | Federal Government | Climate Agency | Education | 10 |

| P5 | Alberta | Provincial Government | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 15+ |

| P6 | Saskatchewan | Water Resources | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 25+ |

| P7 | Manitoba | Engineering Consultant | BRACE Manager | Engineering/Education | 25+ |

| P8 | Manitoba | Engineering Consultant | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 25+ |

| P9 | Manitoba | Professional Regulator | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 15 |

| P10 | Manitoba | Provincial Government | BRACE Manager | Administration | 25+ |

| P11 | Ontario | Climate Consultant | BRACE Manager | Masters Geography | 25+ |

| P12 | Ontario | Climate Consultant | BRACE Manager | Masters Administration | 25+ |

| P13 | Quebec | Researcher | BRACE Manager | PhD. Education | 25+ |

| P14 | Prince Edward Island | Provincial Government | BRACE Project | Masters Environmental | 25+ |

| P15 | Nova Scotia | Engineering Consultant | BRACE Project | Engineering | 20 |

| P16 | New Brunswick | Engineering Consultant | BRACE Project | Masters Engineering | 22 |

| P17 | Prince Edward Island | Provincial Government | BRACE Project | Climate/ Environmental | 10 |

| P18 | New Brunswick | Engineering Consultant | BRACE Project | Engineering | 12 |

| P19 | Newfoundland and Labrador | Researcher | BRACE Manager | PhD. Engineering | 25+ |

| P20 | Newfoundland and Labrador | Graduate Student | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 1 |

| P21 | New Brunswick | Environmental NGO | BRACE Manager | Engineering | 2 |

| Pedagogical Theme | Subtopic | Frequency of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness & Engagement | Codes, standards, and regulations | 7 |

| Professional certifications (PDH, CEUs) | 5 | |

| Time constraints | 4 | |

| Central coordinating entity | 4 | |

| Credible trainers and data | 3 | |

| Competency frameworks | 2 | |

| Reflective Practice | Context-specific training | 9 |

| Qualified trainers with credibility | 3 | |

| Defined competencies | 2 | |

| Formal recognition/certification | 1 | |

| Project-Based Learning | Use of local case studies | 4 |

| Qualified facilitators | 3 | |

| Real-world examples and datasets | 2 | |

| Support for small communities | 2 | |

| Peer knowledge exchange | 1 | |

| Design Thinking | Cross-sector collaboration | 3 |

| Networking and peer exchange | 3 | |

| Local capacity building | 1 | |

| Behavioral change orientation | 1 | |

| Outcome measurement and feedback | 1 |

| Appreciation | Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Brainstorm on climate knowledge and challenges (Acquisition) | Mentorship in the workplace (Execution) | ||

| Integration of an authentic work experience into the training (Authenticity) | Training over several sessions (Execution) | ||

| Site visits (Authenticity) | Refection on own practice (Execution) | ||

| Conceptualization of work context (Authenticity) | Dissemination of training benefits and knowledge sharing (Evaluation) | ||

| Acquisition of globalizing perspectives (Authenticity) | Networking (Evaluation) | ||

| Yes | No | Pedagogical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Does the training rely on the development of values and attitudes rather than on the transmission of a list of ecological techniques or materials to use? (Acquisition) | ||

| Do the engineers have the opportunity to share what they appreciate about climate change, including their social, economic and environmental effects, as well as the adaptative tools they already know? (Acquisition) | ||

| Do the engineers describe their authentic work context and identify the challenges, needs and issues which they face in their daily practice? (Authenticity) | ||

| Do the engineers identify their problems (and their context) rather than the trainer imposing a problem? (Authenticity) | ||

| Are the engineers’ authentic work realities used (directly in the field or as a case study) to contextualize the climate knowledge studied and more importantly, to conceive adaptative climate actions to execute? (Authenticity) | ||

| Are the engineers given time during training to research and identify codes and standards related to adaptation (including techniques and materials) that apply to the case study? (Authenticity) | ||

| Are the engineers proposing general solutions that are then translated into concrete climate actions to be executed relevant to their workplaces while identifying the codes and standards to which they must adhere? (Execution) | ||

| During training, are strategies offered (logbook, questions to answer, verification lists, blogs, etc.) to encourage engineers to constantly exercise professional judgment and to autonomously reflect on their professional activities? (Execution) | ||

| Does the training unfold over several sessions to encourage autonomous execution of climate actions in the workplace and, more particularly, the haring of collaborative reflections on the evaluation of their implementation? (Execution) | ||

| For each action, are the engineers discussing the best ways to evaluate their implementation, its effects on the climate and a cost analysis based on the actions undertaken? (Evaluation) | ||

| Does the training prepare the means of disseminating the benefits and knowledge generated (describe what has been done and what could not be done to attenuate the effects of profes-sional activities on climate change) by using an efficient language designed to inform engineering colleagues, decision makers, the general public, partners or clients? (Evaluation) | ||

| Is the knowledge generated in the training connected to current codes and standards so as to evaluate their relevance and communicate adjustments? (Evaluation) |

| Practice | Description | Case Study (Heat Wave Example) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Brainstorm on climate knowledge | Engineers’ prior knowledge can influence training and must be connected to social, economic and ecological issues. Out of a brainstorming session can emerge climate issues that engineers consider important. Brainstorming activities can be conducted online (ex.: by dividing the participants in expert groups) and in person (ex.: talk shops, discussion groups), and could take place prior to the training activity. | Divided into small groups, the engineers draw up a list of what they know of adaptation (impacts, issues, etc.) and describe the origin of this knowledge (reports, organizations, work documents, etc.). Later, in a big group, the engineers raise the issue of heat waves as an important climate phenomenon and reflect on this change’s social, economic, and environmental consequences. They reflect on the effect of heat waves on their work, and to their activity’s potential contribution to this climate phenomenon. |

| Authenticity | Integration of an authentic work experience into the training | The authentic professional experience of engineers is ideal for contextualizing climate knowledge studied in a training activity. Engineers find more relevance in proposing climate solutions and concrete actions when these relate to an actual situation that is familiar to them. From a climate perspective, engineers can examine future projects, find ways to adapt ongoing projects, and bring to light challenges or obstacles related to their practice. | Each engineer is invited to describe their workplace by articulating their challenges and successes relating to climate change adaptation. During this discussion, they note that several engineers share a common challenge, i.e., the multiplication of urban heat islands during extreme heat waves. |

| Authenticity | Site visits | Access to actual authentic professional situations facilitates the contextualization of climate knowledge, the identification of challenges, the starting point for solutions, and finally, the implementation of climate actions. Staging professional training directly in the field is a way to reinforce the training’s experiential aspect. | During their visit to the field (when accessible, though virtual visits can be enacted remotely), the engineers notice that there are many buildings with either even roof slopes or flat roofs close to the urban heat islands and consider installing vegetation on these roofs as a climate action. Once the climate action is formulated, the engineers identify ways to evaluate the impact installing green roofing could have. |

| Authenticity | Conceptualization of the work context | Engineers have codes and standards that create a framework for the smooth execution of their projects. When training engineers in climate change adaptation, it is important to give them the opportunity to identify the codes and standards that apply to the climate situation studied and to the context of their usual work, knowing that climate solutions and actions must stem from this framework. | The engineers review the codes and standards that apply to their green roof installation project (building codes, construction permits, etc.). They reflect on their understanding of the framework and on ways to implement climate actions that take it into account. This framework, juxtaposed with the proposed climate action—i.e., the installation of vegetation on roofs—determines the latitude of the project, and can inform engineers of potential partners to help modify codes and standards. |

| Authenticity | Acquisition of globalizing perspectives | Climate change engenders various social, economic and political effects that dis-proportionately impact different population groups and requires ethical sensitivity from engineers. Engineers must reflect on the context of their work from the point of view of various stakeholders (the client, surrounding com-munities, the public) and social issues (poverty, inequality and social justice). It is important to nourish engineers’ reflection on their projects’ potential impacts and, if necessary, to create the necessary partnerships required of the expected effects, and in so doing, honour the realities of the various populations involved. Therefore, they reflect on how to execute climate actions that take this framework into account. | By working together, the engineers identify the necessary partnerships (decision makers, citizen groups, First Nations, organizations, etc.) to ensure the smooth installation of green roofs and the acquisition of diverse perspectives on the project. The instructor invites the engineers to reflect on the social objectives connected to the green roofs project, among them its cost, the community resources required for its maintenance, its life span, and its effects on the community involved and its surrounding communities. |

| Practice | Description | Case Study (Heat Wave Example) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Execution | Mentorship in the workplace | Through mentorship, an instructor or colleague offers continuous support to learners by imple-menting climate actions in the field. Mentorship encourages reflection on practices in a collaborative rather than an individual context. Also, mentorship can be enacted periodically through meetings online or on site. | The instructor accompanies an engineer who has participated in heat wave management training through their workday. Together, the instructor and the engineer reflect on the implementation of the target climate action (installation of green roofs) in the engineer’s practice. Mentorship can be enacted periodically through weekly online meetings, for example. |

| Execution | Training over several sessions | Planning a training activity across several sessions facilitates the translation of appreciation into engagement since engineers put the acquired knowledge into practice, reflect on it individually, and discuss it as a group as part of the training. When engineers are in the field with reflective intentions (list of questions, strategies to consider, important data, core issues, etc.) they take the knowledge acquired during training into account, which favours reflection on the role climate change plays on their professional activities. | Discussion groups and visits to the field are periodically organized by the instructor to support engineers’ reflections on the installation of green roofs. The engineers share the challenges they face and their successes since the last session, but more importantly, the ways in which they evaluate their professional activities regarding green roofs. |

| Execution | Reflection on own practice | To encourage the exercise of professional judgment on a daily basis, the engineer is expected to continually reflect on their practice’s effect on the climate, which is however not an innate skill. | The instructor must encourage self-reflection in the engineer before, during and after the action by suggesting reflective intentions and ways to document them (blog, logbook, message board, etc.). The engineers are mandated to share a one sentence reflection on a message board on a particular theme each week (urban heat wave management, urban forestry initiatives, green roof installation, etc.). These reflections are accessible to all participants. |

| Evaluation | Dissemination of training benefits and knowledge sharing | To encourage engineers to evaluate and question what has been done in terms of climate change adaptation, it is important to insert the sharing of generated knowledge into the training itself. The sharing of generated knowledge includes the act of translating success stories, the identification of challenges, and the compromises made during the implementation of climate actions, in a simple and practical language intended for the general public, engineers or decision makers. To this is added a revision of codes and standards that make up the engineer’s work context by suggesting potential updates. | The engineers revisit the building codes related to the green roofs case study and suggest potential updates that can be presented to decision makers (ex.: make green roofs mandatory on certain buildings). The engineers work on jargon-free messaging intended for the public on the heat island phenomenon and its effects. |

| Evaluation | Networking | The interdisciplinary nature of engineering projects reinforces the importance of working collectively rather than in silos. The identification of potential partners (other than engineers) is particularly suitable to training activities. Yet, meeting such partners during networking activities, whether online or in person, can also be part of the training (break-fast meetings, pairing activities, training sessions, etc.). | The instructor invites one of the partners (i.e., the apartment building tenant committee) identified during the appreciation phase of the green roof installation project to discuss with the engineers, their issues and expected outcomes and what type of collaboration is expected from such a project. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dupuis, S.T.; Gagnon, S.; LeBlanc, C.E. Building Climate Adaptation Capacity: A Pedagogical Model for Training Civil Engineers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210200

Dupuis ST, Gagnon S, LeBlanc CE. Building Climate Adaptation Capacity: A Pedagogical Model for Training Civil Engineers. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210200

Chicago/Turabian StyleDupuis, Serge T., Samuel Gagnon, and Catherine E. LeBlanc. 2025. "Building Climate Adaptation Capacity: A Pedagogical Model for Training Civil Engineers" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210200

APA StyleDupuis, S. T., Gagnon, S., & LeBlanc, C. E. (2025). Building Climate Adaptation Capacity: A Pedagogical Model for Training Civil Engineers. Sustainability, 17(22), 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210200