Source Apportionment of Urban GHGs in Hong Kong from Regional Transportation Based on Diagnostic Ratio Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Instruments and Analytical Tools

2.1. Observation Site

2.2. Apparatus and Data Source

2.2.1. Online Measurements

Calibration and QA/QC

2.2.2. Laboratory Analysis

2.2.3. Meteorological Parameters

2.2.4. Other Data Sets and Analytical Tools

3. Results and Discussion

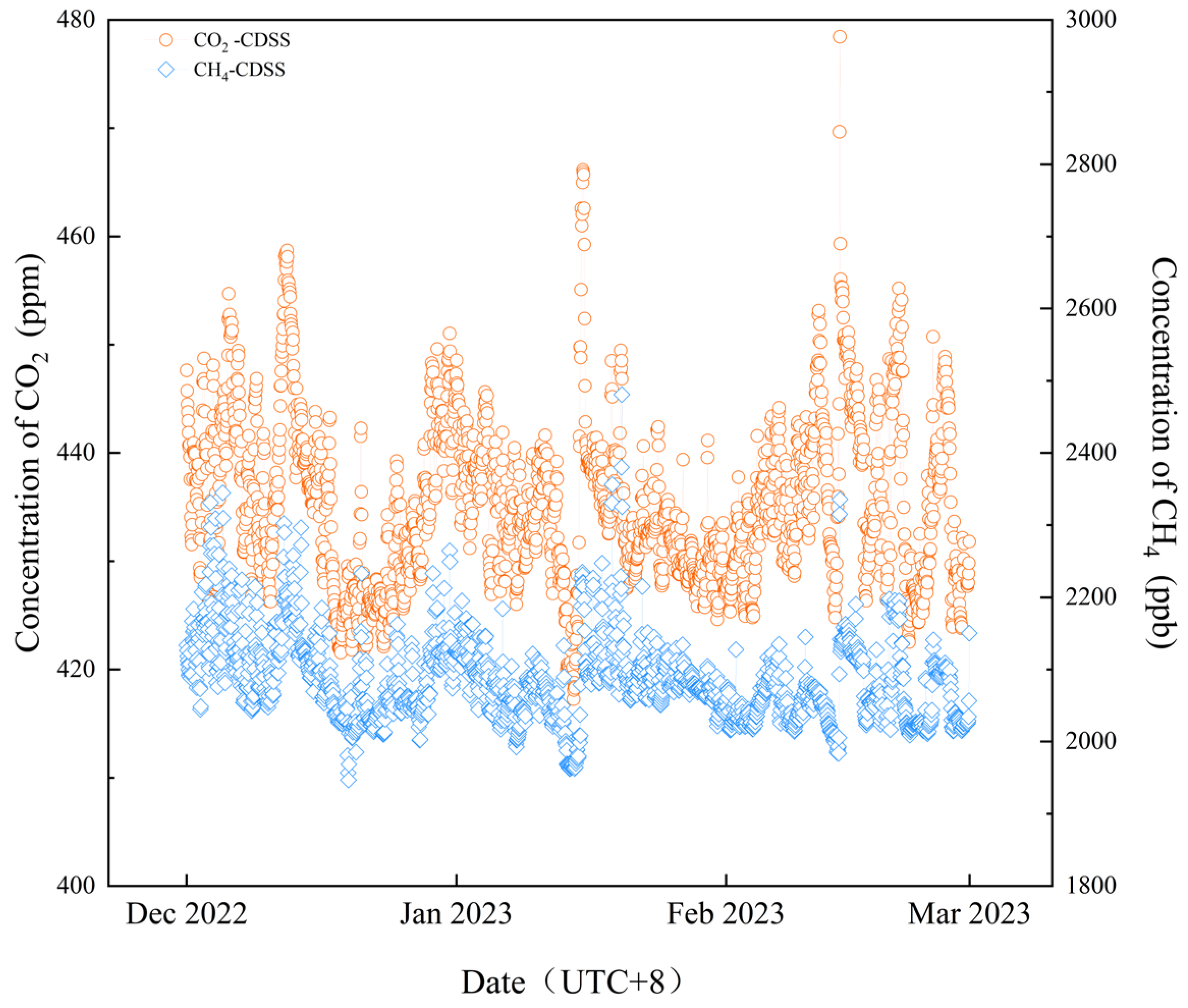

3.1. Characteristics of CO2 and CH4 Levels in Winter

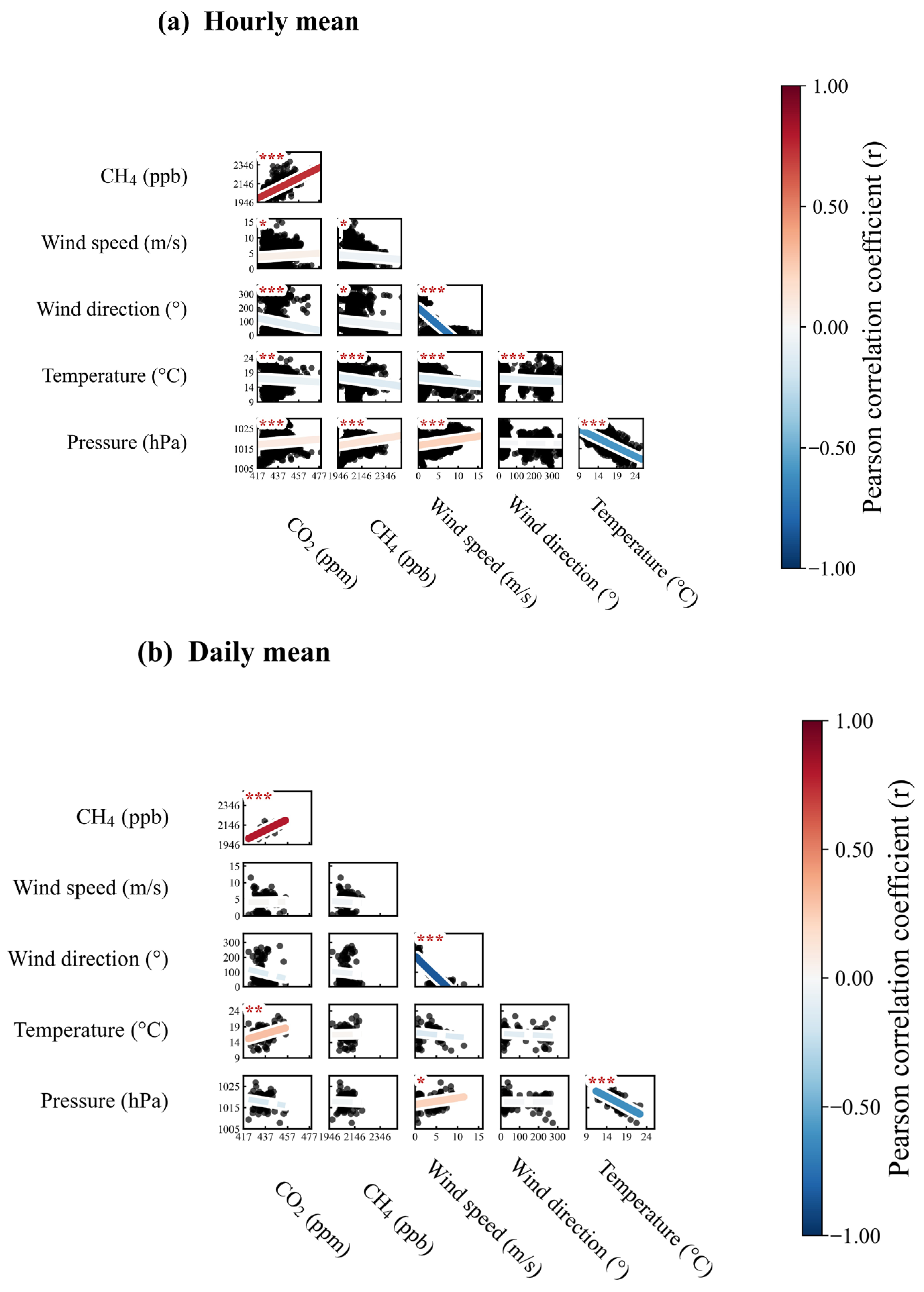

3.2. Correlation Analysis

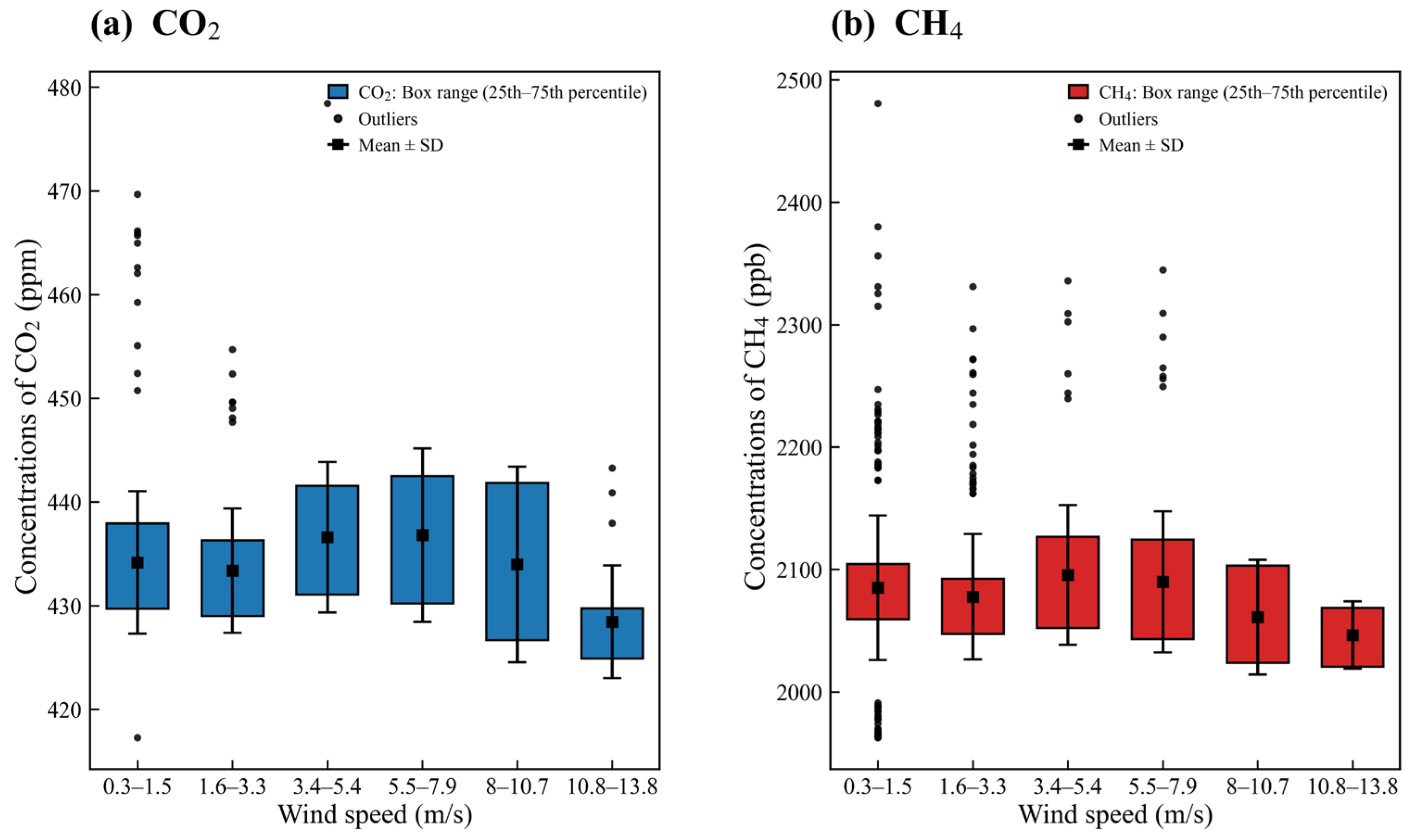

3.3. Source Distance Theory

3.4. Assessment of Transportation

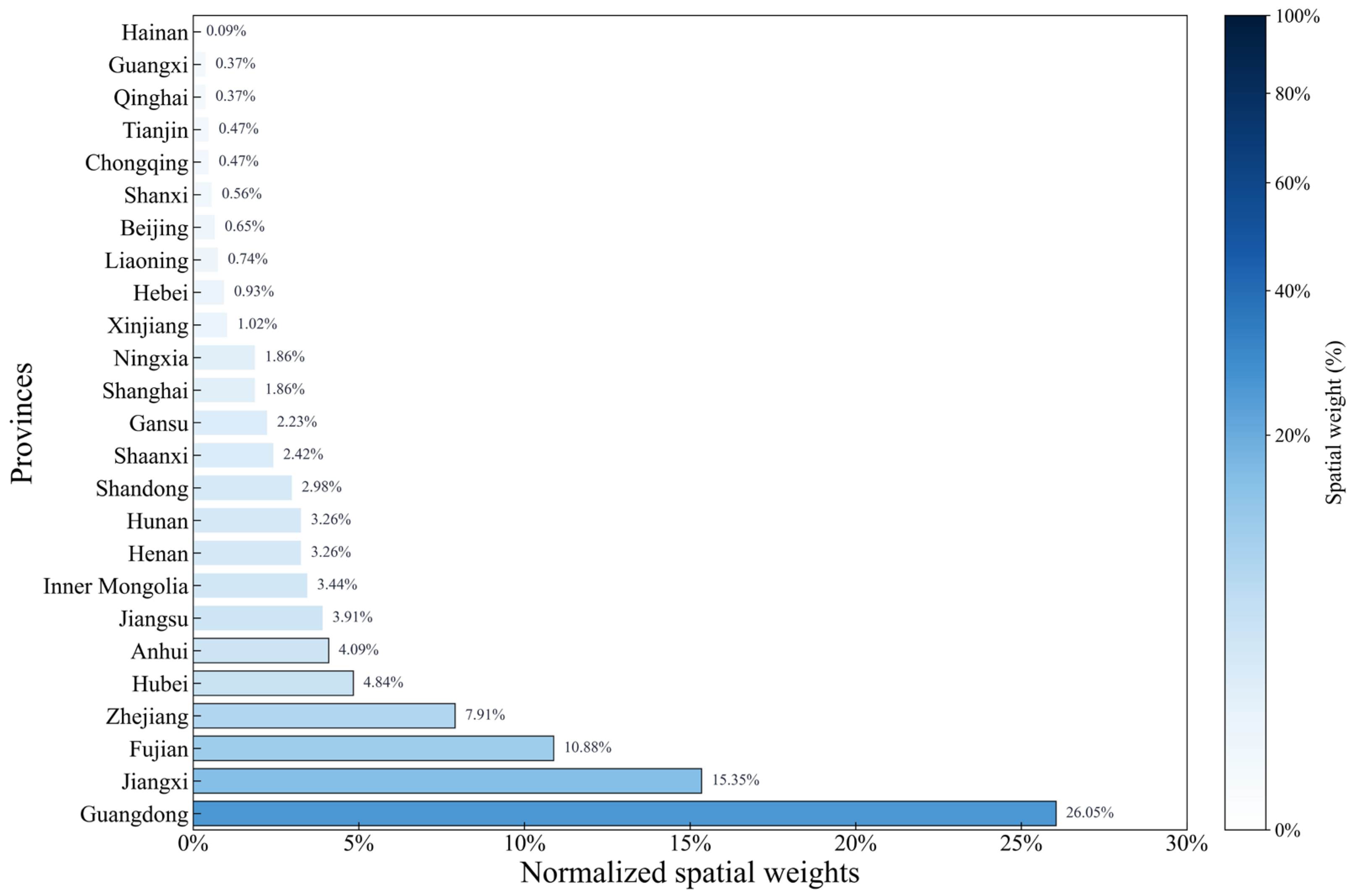

3.4.1. Identification of Regional Transport Events and Provincial Spatial Weighting

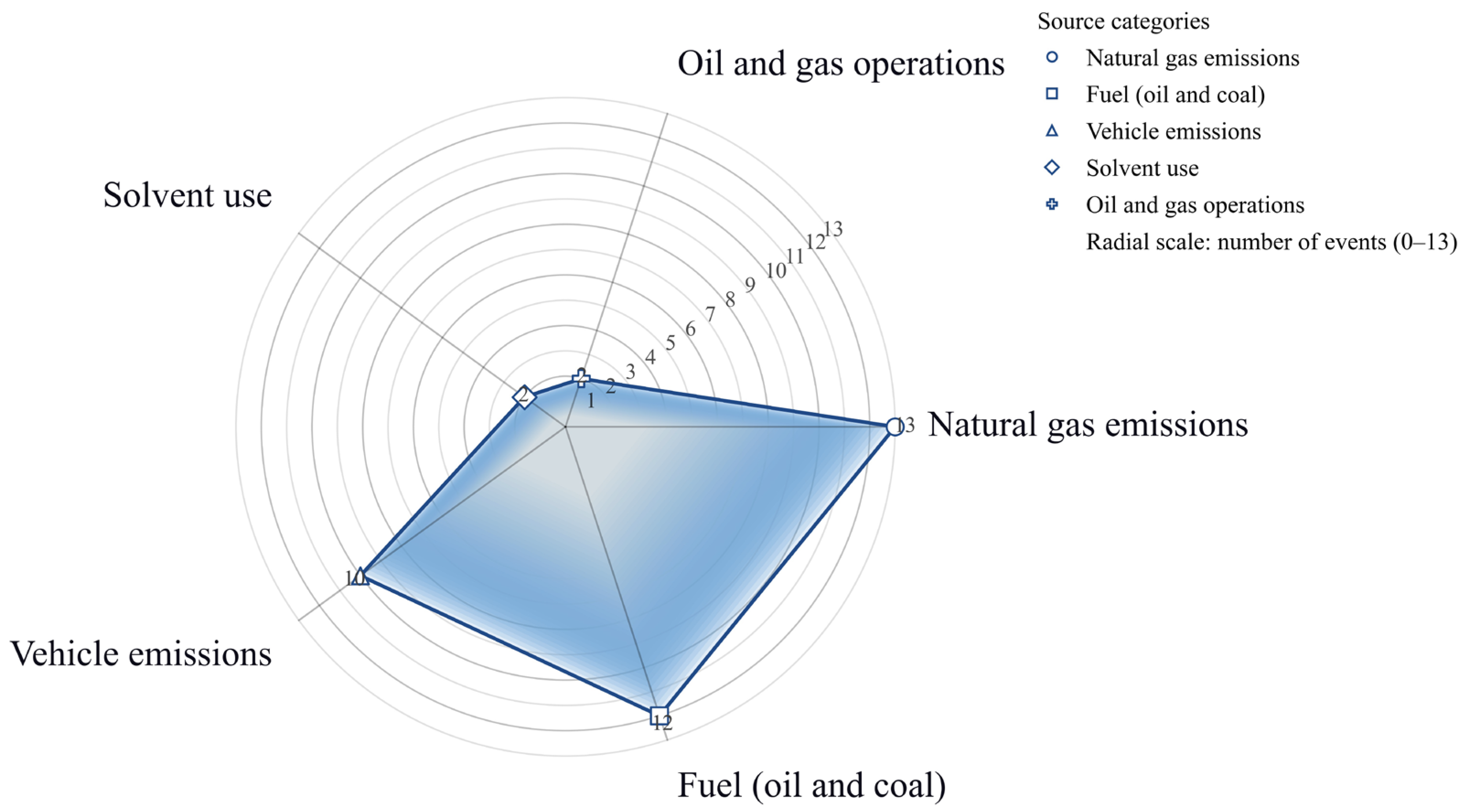

3.4.2. Source Attribution and Emission-Inventory Reconstruction

- (1)

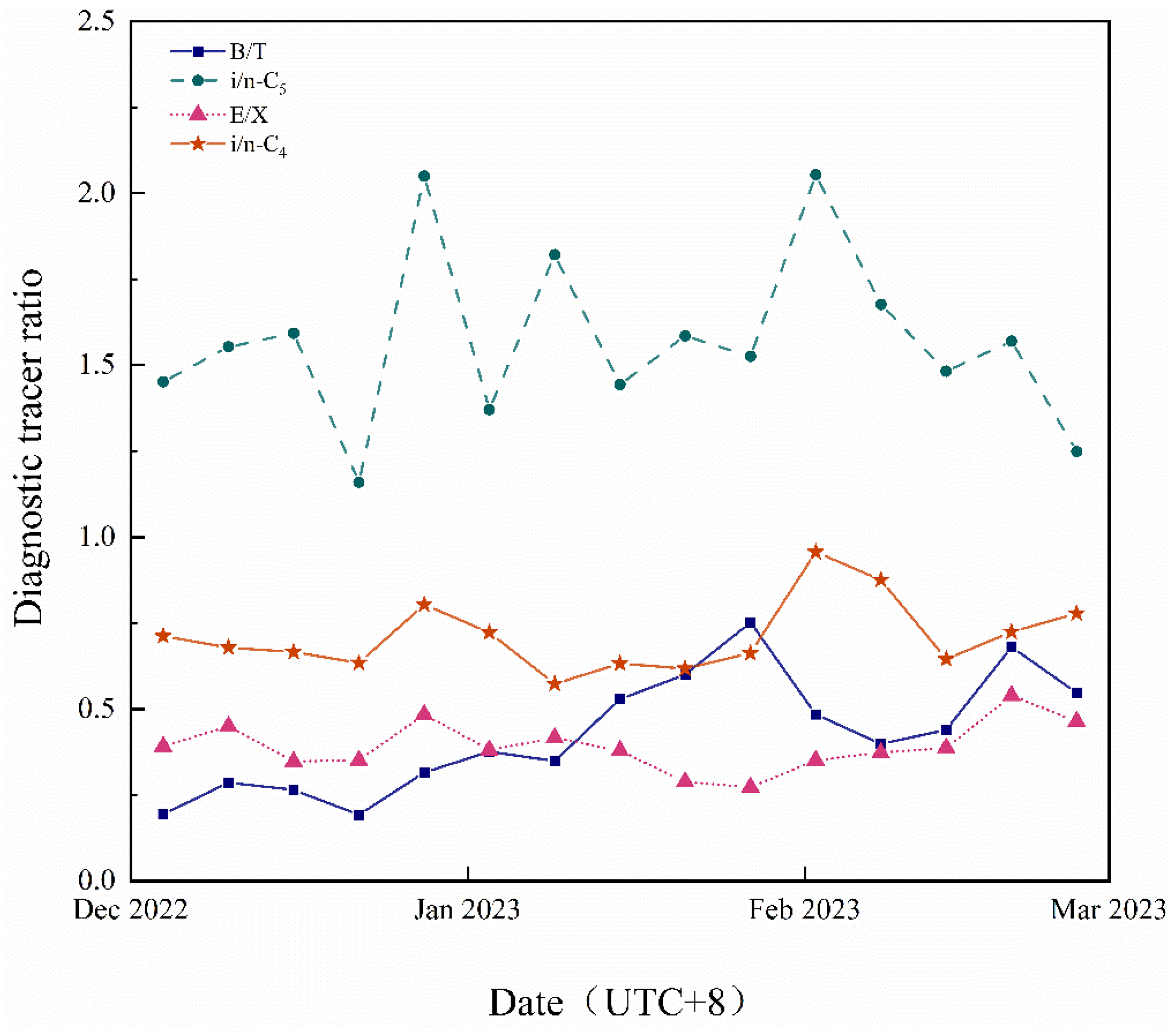

- Benzene/Toluene (B/T) Ratio

- (2)

- Isopentane/n-Pentane (i/n-C5) Ratio

- (3)

- Isobutane/n-Butane (i/n-C4) Ratio

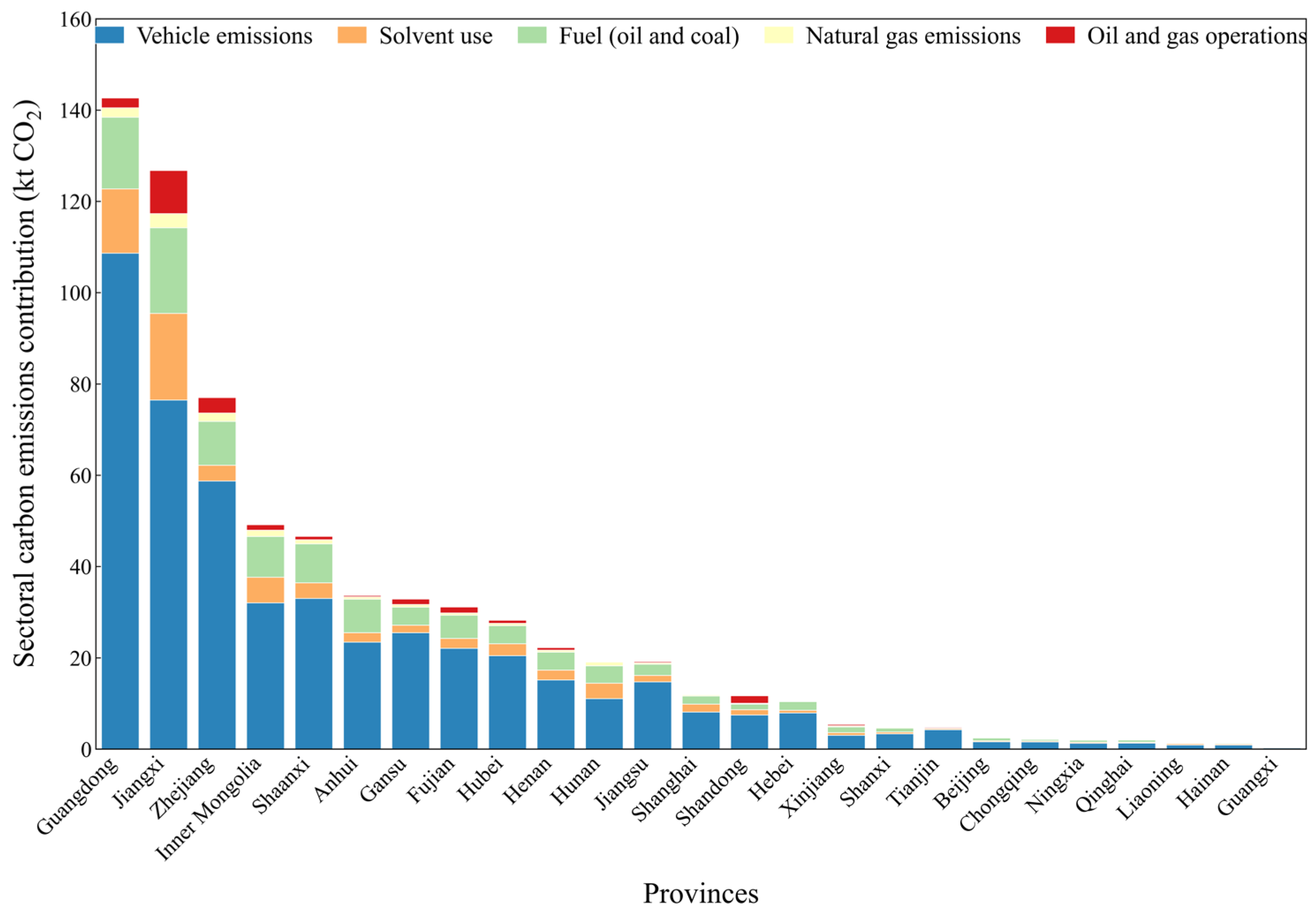

3.4.3. Quantifying Provincial and Sector Contributions to Cross-Regional GHG Transport

3.5. Uncertainty Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harde, H. Radiation and heat transfer in the atmosphere: A comprehensive approach on a molecular basis. Int. J. Atmos. Sci. 2013, 2013, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 19: The State of Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere Based on Global Observations Through 2022; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://public.wmo.int/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P.; Zhang, L.; Hurynovich, V.; He, Y. Greenhouse gases emissions and global climate change: Examining the influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harriss, R.C.; Sebacher, D.I.; Day, F.P. Methane flux in the Great Dismal Swamp. Nature 1982, 297, 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, D.; Shao, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; He, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24463–24469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Xu, S.; Cao, J.; Ren, F.; Wei, W.; Meng, J.; Wu, L. Air pollution reduction and climate co-benefits in China’s industries. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Wang, P.; Yu, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H. Drivers of alleviated PM2.5 and O3 concentrations in China from 2013 to 2020. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, H.M.; Guo, K.D.; Liu, Y. Research Progress on Cooperative Governance of Greenhouse Gases and Air Pollutants. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, P.; Brandon, N.P.; Hawkes, A.D. Characterising the distribution of methane and carbon dioxide emissions from the natural gas supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.P.; Gao, S.; Gonzales, M.; Thao, T.; Bischak, E.; Ghezzehei, T.A.; Berhe, A.A.; Diaz, G.; Ryals, R.A. Dairy manure co-composting with wood biochar plays a critical role in meeting global methane goals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10987–10996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rabaza, J.A.; Andrade, J.L.; Us-Santamaría, R.; Morales-Rico, P.; Mayora, G.; Aguirre, F.J.; Fecci-Machuca, V.; Gade-Palma, E.M.; Thalasso, F. Impacts of leaks and gas accumulation on closed chamber methods for measuring methane and carbon dioxide fluxes from tree stems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpasi, S.O.; Akpan, J.S.; Amune, U.O.; Olaseinde, A.A.; Kiambi, S.L. Methane advances: Trends and summary from selected studies. Methane 2024, 3, 276–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sheng, L.F.; Wang, W.C.; Yu, J.Z. Circulation clustering characteristics causing air pollution in Hong Kong and their impact on fine particulate matter. Geochimica 2021, 50, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lyu, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zou, S.; Ling, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, F.; Zeren, Y.; Pan, W.; et al. Ozone pollution around a coastal region of South China Sea: Interaction between marine and continental air. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 4277–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianghong, H.; Yue, L.; Ying, Z.; Qinyu, C.; Xiuyong, Z.; Dongsheng, C. The ozone concentration and changes in the sensitivity of its formation in Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) from a carbon neutral perspective. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 15, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, C.; Augustin, P.; Leroy, C.; Willart, V.; Delbarre, H.; Khomenko, G. Impact of a sea breeze on the boundary-layer dynamics and the atmospheric stratification in a coastal area of the North Sea. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2007, 125, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.A.; de Arellano, J.V.-G.; Dudhia, J.; Bosveld, F.C. Role of synoptic- and meso-scales on the evolution of the boundary-layer wind profile over a coastal region: The near-coast diurnal acceleration. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2015, 128, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipalatkar, P.; Khaparde, V.V.; Gajghate, D.G.; Bawase, M.A. Source apportionment of PM2.5 using a CMB model for a centrally located Indian city. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Choudhary, N.; Masiwal, R.; Saxena, M.; Sharma, A.; Mandal, T.K.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, N.C.; Sharma, C. Chemical characteristics and source apportionment of PM2.5 using PCA/APCS, UNMIX, and PMF at an urban site of Delhi, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 14637–14656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hussain, S.A.; Sobri, S.; Md Said, M.S. Overviewing the air quality models on air pollution in Sichuan Basin, China. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hui, L.; Wang, M.; Xia, M.; Zou, Z.; Wei, W.; Ho, K.F.; Wang, Z.; et al. Origin and transformation of volatile organic compounds at a regional background site in Hong Kong: Varied photochemical processes from different source regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draxler, R.R.; Hess, G.D. An overview of the HYSPLIT_4 modelling system for trajectories, dispersion, and deposition. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 1998, 47, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.C.; Pleim, J.; Mathur, R.; Binkowski, F.; Otte, T.; Gilliam, R.; Pouliot, G.; Xiu, A.; Young, J.O.; Kang, D. WRF-CMAQ two-way coupled system with aerosol feedback: Software development and preliminary results. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhou, X. A review of the CAMx, CMAQ, WRF-Chem and NAQPMS models: Application, evaluation and uncertainty factors. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.K.; Huang, X.H.H.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Yu, J.Z. Estimating primary vehicular emission contributions to PM2.5 using the chemical mass balance model: Accounting for gas–particle partitioning of organic aerosols and oxidation degradation of hopanes. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Han, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Lee, S. Characteristics and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at a coastal site in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ho, S.S.H.; Man, C.L.; Qu, L.; Wang, Z.; Ning, Z.; Ho, K.F. Characteristics and sources of oxygenated VOCs in Hong Kong: Implications for ozone formation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosson, E.R. A cavity ring-down analyzer for measuring atmospheric levels of methane, carbon dioxide, and water vapor. Appl. Phys. B 2008, 92, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Winderlich, J.; Gerbig, C.; Hoefer, A.; Rella, C.W.; Crosson, E.R.; Van Pelt, A.D.; Steinbach, J.; Kolle, O.; Beck, V.; et al. High-accuracy continuous airborne measurements of greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4) using the cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) technique. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2010, 3, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.R.; Smith, T.W.; Chen, T.-Y.; Whipple, W.J.; Rowland, F.S. Effects of biomass burning on summertime nonmethane hydrocarbon concentrations in the Canadian wetlands. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 1699–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, T.W.; Vogt, R.; Oncley, S.P. Measurements of flow distortion within the IRGASON integrated sonic anemometer and CO2/H2O gas analyzer. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2016, 160, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhen, X.; Li, Y.; Hao, G.; Shen, H.; Gao, T.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, N. Recovery of the three-dimensional wind and sonic temperature data from a physically deformed sonic anemometer. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 5981–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Data Centre for Greenhouse Gases (WDCGG). WMO GAW World Data Centre for Greenhouse Gases. Available online: https://gaw.kishou.go.jp/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Li, K.; Jacob, D.J.; Liao, H.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Bates, K.H. Anthropogenic drivers of 2013–2017 trends in summer surface ozone in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, D.; Chen, C.; Hong, C.; Li, M.; Geng, G.; Lei, Y.; Huo, H.; He, K. Resolution dependence of uncertainties in gridded emission inventories: A case study in Hebei, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Tong, D.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Hong, C.; Geng, G.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Peng, L.; Qi, J.; et al. Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 14095–14111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Cheng, J.; Yan, L.; Wu, N.; Hu, H.; Tong, D.; Zheng, B.; et al. Efficacy of China’s clean air actions to tackle PM2.5 pollution between 2013 and 2020. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centers for Environmental Prediction; National Weather Service; NOAA; U.S. Department of Commerce. NCEP FNL Operational Model Global Tropospheric Analyses, Continuing from July 1999 (1° × 1° Global Grid, Updated Daily); Research Data Archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Computational and Information Systems Laboratory: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; Rolph, G.D.; Stunder, B.J.B.; Cohen, M.D.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Lau, A.K.H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.Z.; Louie, P.K.K.; Fung, J.C.H. Identification and spatiotemporal variations of dominant PM10 sources over Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Fung, J.C.H.; Yao, T.; Lau, A.K.H. A study of control policy in the Pearl River Delta region by using the particulate matter source apportionment method. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 76, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.W.; He, G.; Pan, Y. Mitigating the air pollution effect? The remarkable decline in the pollution–mortality relationship in Hong Kong. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2020, 101, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, G.; Guan, D. Emissions and low-carbon development in Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area cities and their surroundings. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Rajesh, T.A. Black carbon aerosol mass concentrations over Ahmedabad, an urban location in western India: Comparison with urban sites in Asia, Europe, Canada, and the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D06211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, P.; Sharma, N.; Dadhwal, V.K.; Rao, P.V.N.; Apparao, B.V.; Ghosh, A.K.; Mallikarjun, K.; Ali, M.M. Impact of land–sea breeze and rainfall on CO2 variations at a coastal station. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2014, 5, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.X.; Tans, P.P.; Steinbacher, M.; Zhou, L.X.; Luan, T. Comparison of the regional CO2 mole fraction filtering approaches at a WMO/GAW regional station in China. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 5301–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R.; Briggs, G.A.; Hosker, R.P., Jr. Handbook on Atmospheric Diffusion; U.S. Department of Energy, Technical Information Center: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1982; Report No. DOE/TIC-11223 (DE82002045).

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, G.P.; Jacob, D.J. Modeling of Atmospheric Chemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Meteorological Administration (CMA). Regulations on Typhoon Operations and Services; China Meteorological Administration: Beijing, China, 2001. Available online: https://www.cma.gov.cn/kppd/kppdsytj/201508/t20150808_290036.html (accessed on 20 January 2025). (In Chinese)

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Manual on Marine Meteorological Services. Volume I—Global Aspects. WMO-No. 558; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/bitstream/handle/11329/119/wmo_558_en-v1.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Rappenglück, B.; Fabian, P.; Kalabokas, P.; Viras, L.G.; Ziomas, I.C. Quasi-continuous measurements of non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHC) in the Greater Athens Area during MEDCAPHOT-TRACE. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 2103–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, A.; Sive, B.C.; Avino, P.; Chen, T.; Blake, D.R.; Rowland, F.S. Monoaromatic compounds in ambient air of various cities: A focus on correlations between the xylenes and ethylbenzene. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, M.; Fu, L.; Lu, S.; Zeng, L.; Tang, D. Source profiles of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) measured in China: Part I. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 6247–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Shao, M.; Lu, S.; Wang, B. Source profiles of volatile organic compounds associated with solvent use in Beijing, China. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, S.; Huang, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y. Ambient air benzene at background sites in China’s most developed coastal regions: Exposure levels, source implications and health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Bari, M.A.; Xing, Z.; Du, K. Ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in two coastal cities in western Canada: Spatiotemporal variation, source apportionment, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, B.; Meinardi, S.; Simpson, I.J.; Zou, S.; Sherwood Rowland, F.; Blake, D.R. Ambient mixing ratios of nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) in two major urban centers of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region: Guangzhou and Dongguan. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 4393–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.L.; Lonneman, W.A.; Seila, R.L. Transportation-related volatile hydrocarbon source profiles measured in Atlanta. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1995, 45, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.G.; Chow, J.C.; Fujita, E.M. Review of volatile organic compound source apportionment by chemical mass balance. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 1567–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaughey, G.R.; Desai, N.R.; Allen, D.T.; Seila, R.L.; Lonneman, W.A.; Fraser, M.P.; Harley, R.A.; Pollack, A.K.; Ivy, J.M.; Price, J.H. Analysis of motor vehicle emissions in a Houston tunnel during the Texas Air Quality Study 2000. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 3363–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.S.; Zhou, Y.; White, M.L.; Mao, H.; Talbot, R.; Sive, B.C. Multi-year (2004–2008) record of nonmethane hydrocarbons and halocarbons in New England: Seasonal variations and regional sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 4909–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, J.B.; Burkhart, J.F.; Lerner, B.M.; Williams, E.J.; Kuster, W.C.; Goldan, P.D.; Murphy, P.C.; Warneke, C.; Fowler, C.; Montzka, S.A.; et al. Ozone variability and halogen oxidation within the Arctic and sub-Arctic springtime boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 10223–10236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, J.B.; Lerner, B.M.; Kuster, W.C.; de Gouw, J.A. Source signature of volatile organic compounds from oil and natural gas operations in northeastern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Hong, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Characteristics of atmospheric volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at a mountainous forest site and two urban sites in the southeast of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Liu, X.; Tan, Q.; Feng, M.; An, J.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhai, R.; Wang, Z. VOC characteristics, chemical reactivity and sources in urban Wuhan, central China. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 224, 117340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Lamb, B.; Westberg, H.; Allwine, E.; Sosa, G.; Arriaga-Colina, J.L.; Jobson, B.T.; Alexander, M.L.; Prazeller, P.; Knighton, W.B.; et al. Distribution, magnitudes, reactivities, ratios and diurnal patterns of volatile organic compounds in the Valley of Mexico during the MCMA 2002 & 2003 field campaigns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; He, X.; Mu, Y. Ambient volatile organic compounds in urban and industrial regions in Beijing: Characteristics, source apportionment, secondary transformation and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; He, T.; Yi, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; He, K. Advancing shipping NOx pollution estimation through a satellite-based approach. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgad430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Latitude | Longitude | CO2 Maximum | CO2 Minimum | CO2 Mean | CH4 Maximum | CH4 Minimum | CH4 Mean | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (North: +; South: −) | (East: +; West: −) | (ppm) | (ppm) | (ppm) | (ppb) | (ppb) | (ppb) | ||

| MLO | 19.54 | −155.58 | 424.42 | 418.81 | 420.11 ± 1.31 | 1952.34 | 1929.34 | 1939.38 ± 8.98 | WDCGG |

| MKO | 19.83 | −155.48 | 425.53 | 416.01 | 419.76 ± 0.98 | 1989.31 | 1901.68 | 1943.57 ± 12.16 | WDCGG |

| CDSS | 22.22 | 114.25 | 478.44 | 417.27 | 435.29 ± 7.64 | 2480.84 | 1946.92 | 2083.45 ± 56.50 | This study |

| LLN | 23.47 | 120.87 | 424.99 | 419.30 | 422.05 ± 1.73 | 1983.87 | 1926.67 | 1967.31 ± 15.59 | WDCGG |

| MNM | 24.29 | 153.98 | 429.84 | 417.48 | 422.08 ± 1.85 | 2021.00 | 1930.00 | 1979.25 ± 16.32 | WDCGG |

| GSN | 33.29 | 126.16 | 455.65 | 420.63 | 430.11 ± 5.21 | 2215.32 | 1986.08 | 2040.22 ± 32.36 | WDCGG |

| RYO | 39.03 | 141.82 | 454.12 | 420.74 | 427.53 ± 3.37 | 2072.00 | 1986.00 | 2018.59 ± 13.32 | WDCGG |

| Major Source in Reconstructed Inventory | Sectors in the High-Resolution Inventory (MEIC) |

|---|---|

| Natural gas emissions | Gas works, gasification plants, liquefaction/regasification plants, pipeline transport |

| Fuel (oil and coal) | Oil refineries, coal liquefaction, GTL plants |

| Vehicle emissions | Cars, light-duty trucks, buses, heavy-duty trucks, motorcycles, other fleets |

| Solvent use | Chemical, pulp and paper, wood product, textile and leather industries |

| Oil and gas operations | Oil and gas extraction, transport equipment *, domestic navigation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Chiu, A.W.L.; Tsui, W.B.C.; Mak, G.Y.H.; Ma, N.; Qin, J. Source Apportionment of Urban GHGs in Hong Kong from Regional Transportation Based on Diagnostic Ratio Method. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210099

Xu Y, Wang J, Zhu L, Chiu AWL, Tsui WBC, Mak GYH, Ma N, Qin J. Source Apportionment of Urban GHGs in Hong Kong from Regional Transportation Based on Diagnostic Ratio Method. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210099

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yiwei, Jie Wang, Libin Zhu, Aka W. L. Chiu, Wilson B. C. Tsui, Giuseppe Y. H. Mak, Na Ma, and Jie Qin. 2025. "Source Apportionment of Urban GHGs in Hong Kong from Regional Transportation Based on Diagnostic Ratio Method" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210099

APA StyleXu, Y., Wang, J., Zhu, L., Chiu, A. W. L., Tsui, W. B. C., Mak, G. Y. H., Ma, N., & Qin, J. (2025). Source Apportionment of Urban GHGs in Hong Kong from Regional Transportation Based on Diagnostic Ratio Method. Sustainability, 17(22), 10099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210099