1. Introduction

Societal well-being is inseparable from the synergy between welfare state objectives, social policy actions, effective governance, and positive economic development. Political discourse in different contexts reflects a consistent emphasis on ensuring equal opportunities and reducing inequality, which are also central to sustainable development. For example, in 2016, the United States President Donald Trump declared that the American Dream was “dead,” while committing to its restoration [

1]. Similarly, former UK Prime Minister Theresa May emphasized that the opportunity should not be restricted to “the privileged few,” but should be accessible to all, regardless of background [

2]. Furthermore, the program of Lithuania’s 18th Government [

3] pledged to ensure equal educational opportunities for all children, regardless of residence or socio-economic status. Such statements underscore not only the persistence of inequality rooted in social origins but also its recognition as a pressing policy issue. In addition, they highlight the link between inequality reduction and long-term social sustainability. Evidence from Lithuania confirms this concern: Vilnius University survey data [

4] show that students from low socio-economic backgrounds are four times less likely to enter higher education, thus limiting their opportunities to accumulate human capital and access higher-skilled professions.

It is important to emphasize that social mobility is a concern not only for individual countries but also for many international organizations, such as Eurofound, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United Nations (UN), and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). These organizations emphasize social policy objectives that increasingly focus on improving the social and economic situation of young people, ensuring equal opportunities, and mitigating structural barriers to the intergenerational transmission of status, making the issue of social mobility particularly pressing and relevant [

5]. The OECD has also highlighted the importance of social policy and related reforms that can reduce barriers to intergenerational mobility, thus addressing inequality [

6]. Moreover, for more than a decade, the United Nations has focused on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), many of which are directly or indirectly linked to social mobility through their targets and indicators. Collectively, these organizations contribute to the improvement of social and economic conditions through a variety of measures, including systematic collection and analysis of data, monitoring of political processes, provision of recommendations, allocation of funding, and other forms of policy support. In this sense, social mobility functions both as a means to achieve sustainable development and as an indicator of societal openness and inclusion.

In the academic field, international research has extensively examined social mobility. Sorokin [

7] provided its foundational conceptualization, while Blau and Duncan’s The American Occupational Structure [

8] introduced the influential status attainment model, linking family history to children’s educational and occupational outcomes. Although widely applied across countries, this model has received little attention in Lithuanian scholarship, where studies remain fragmented, focusing on definitions, typologies, post-socialist transitions, or specific cohorts [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Consequently, only a partial picture of social mobility in Lithuania has been revealed. A comprehensive, data-driven study is lacking, particularly one that situates social mobility within the broader framework of sustainable development and the reduction of intergenerational inequality.

This study addresses a central research question: to what extent is social mobility in present-day Lithuania shaped by parental socio-economic status? The objective is to identify which family characteristics foster mobility through education and occupation and to determine the factors of the greatest influence. Two hypotheses are proposed:

H1. The education and occupation of fathers exert the strongest influence on children’s education.

H2. The combined effect of maternal and paternal education has a significant impact on children’s occupation.

To test these hypotheses, data from the European Social Survey (2020) [

14] were analyzed using descriptive, correlational, and regression methods. The focus is on intergenerational mobility. Individual characteristics of the respondents were not included in the analysis, which represents a limitation. However, the findings are expected to enhance the understanding of social mobility in Lithuania and provide a foundation for future research, while also forming policies that link mobility with sustainability goals.

This article makes several important contributions. First, it bridges the fields of sociology, economics, and sustainable development by exploring intergenerational social mobility as both a driver and indicator of sustainability, thus addressing the research gap in connecting mobility studies with sustainable development. Second, it presents evidence from an Eastern European country—Lithuania—illustrating how structural transformations, such as post-Soviet reforms and EU integration, shape educational and occupational trajectories. In doing so, it supports the argument that systemic change may interact with family background to determine life outcomes. Third, it advances fundamental sociological literature by incorporating both maternal and paternal characteristics, as well as gender-sensitive dimensions, into the status attainment framework, thus offering a novel approach to linking classical theories with contemporary social realities. Finally, the study provides governance-oriented recommendations, offering actionable insights for policymakers seeking to design strategies that foster social mobility, reduce inequality, and strengthen sustainable development.

The article is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the concept and types of social mobility and outlines the research strategies;

Section 3 presents the materials and methods;

Section 4 reports the empirical results and analysis, with particular reference to their interfaces with sustainable development;

Section 5 presents the discussion and recommendations based on the results. The conclusion reflects on the main implications and challenges.

2. Literature Analysis

2.1. Types of Social Mobility

The study of social mobility originated with Sorokin’s assertion that it represents the movement of an individual or any social object or value from one social position to another [

7]. In simpler terms, it refers to the movement of individuals, families, or other social units between different positions within the societal stratification system. As a central object of investigation, social mobility has been a popular topic in sociological research for more than three decades [

10]. Scholars have sought to determine how the positions of individuals in society change and which specific factors influence upward or downward movement within the social hierarchy. This underscores the need to discuss social mobility as a sociological phenomenon by addressing its conceptual foundations and examining its implications for reducing inequality and supporting sustainable development.

The late twentieth century was marked by what both policymakers and scholars referred to as the ‘end of class’, which was theoretically expected to create more favorable conditions to reduce inequality and shape various social processes, regardless of socio-economic status. Later, the perspective shifted toward meritocracy, which was expected to trigger a boom in social mobility. Sorokin [

7] emphasized that no society is completely open (based on class) or completely closed (as in the caste system of India). This means that social change occurs over time, as individuals move from one position to another through various forms of social interaction. Mobility generally benefits societies as individuals are motivated by different factors. For example, people work to obtain new roles that offer a higher standard of living and better remuneration. They compete and collaborate with others in society to climb the ladder of mobility [

7]. Werner [

15] defines social mobility in a way that echoes Sorokin [

7], describing it as movement between social positions within a multidimensional social space. Aldridge similarly defines social mobility as movement (or the possibility of movement) between different social classes and occupational groups [

16]. Thus, it can be argued that there is a broad academic consensus on the concept of social mobility and its key characteristics, with education and occupational achievement commonly emphasized as central drivers of both personal advancement and societal progress.

Researchers interested in social mobility focus mainly on intergenerational mobility, examining the relationship between the educational and occupational status of parents and that of their children. Breen and Jonsson [

17] conclude that social mobility can be understood as the evaluation of an individual’s social origins relative to their current social position, revealing the degree of openness within a society. In open societies, the institutional environment allows young people from families of lower social status to attain higher levels of education and rise within the social hierarchy [

18]. However, higher levels of education do not always correspond to higher levels of occupational prestige or higher earnings, highlighting the challenge of ensuring that education translates into sustainable and equitable outcomes.

Most historical studies of social mobility use occupation as an indicator of social status rather than education, income, or wealth. Nevertheless, occupation has been observed to be the most common indicator of social mobility among sociologists, while income is used more frequently by economists [

19]. Since theoretical analyses reveal that sociological research places the greatest emphasis on educational and career achievements, this study also focuses on these variables. In addition, a review of the literature reveals that social mobility is a multifaceted phenomenon that can manifest in diverse forms. Individuals may encounter different types of mobility at various stages of life, reflecting the dynamic and context-dependent nature of social movement. These forms of mobility can be classified into distinct types and are subject to evaluation and measurement using different research strategies. Two primary types are distinguished: horizontal and vertical mobility. Horizontal social mobility is associated with changes in physical location or occupation without alterations in an individual’s economic status, prestige, or lifestyle. In contrast, vertical social mobility is characterized by upward or downward movement within the social hierarchy. Although vertical mobility has received greater academic attention, it is important to address the conceptual foundations of both types [

7]. Other types reflecting the multifaceted nature of the concept of social mobility include Sorokin’s [

7] theoretical distinctions between intergenerational and intragenerational mobility. Intergenerational mobility is defined as the movement between generations (parents and children and/or grandchildren), whereas intragenerational mobility refers to changes observed throughout a person’s life course [

20]. In the analysis of intergenerational movement, a distinction is made between structural (absolute) and relative social mobility. Structural mobility reflects the overall number of individuals who have moved to a different level within the social structure [

20]. Relative mobility, by contrast, refers to the likelihood or probability of changing one’s social position compared to that of one’s parents. Both forms are highly relevant for transitional societies such as Lithuania, where systemic changes create opportunities for upward movement but also pose risks of reproducing inequality.

2.2. Social Mobility Research Strategies

Social mobility has often been viewed in terms of its role in shaping social classes and groups. Subsequent research, however, has increasingly sought to determine the degree to which the social opportunities to individuals are shaped by their socioeconomic origins. Empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of prior occupational achievements, educational attainment, and parental status in shaping employment prospects and social standing at different stages of a career. For this reason, it is essential to discuss the main strategies that can facilitate a deeper understanding of the approaches employed in the study of social mobility, particularly with regard to the reduction of intergenerational inequality and its contribution to sustainable development.

A common point of departure in many studies is the status-attainment framework, initially developed through the seminal research of Blau and Duncan [

8]. The primary objective of this approach is to understand how family background (economic origin) relates to educational attainment and occupational position within society. Blau and Duncan [

8] demonstrated how the education and occupational status of a father influence the son’s education, as well as subsequent variables such as initial job placement and later career achievements. Although parental occupation exerts a direct effect, the principal influence on occupational attainment is indirect, operating through education. Education, in turn, affects both early and later occupational outcomes. The distinction between direct and indirect parental influences underscores the greater importance of education compared to parental occupation. In all cases, the direct effect on occupational status is considerably weaker than the effect mediated first by education and subsequently by occupation. This finding confirms that a child’s educational attainment has a much stronger impact on occupational achievements than the corresponding status of the parents [

8]. Thus, it was concluded that in the mid-20th-century United States, individual characteristics outweighed ascribed family socioeconomic background in determining occupational status. Such insights remain highly relevant for transitional societies such as Lithuania, where education is regarded as a key lever of upward mobility and a foundation for sustainable social progress.

However, this framework has faced criticism for focusing exclusively on male social mobility. In its classical formulation, it overlooked the fact that women constitute more than half of the global population and that single-parent households are also a prevalent phenomenon. As a result, studies comparing only fathers and sons, along with their socioeconomic status, reflect only male trajectories and do not represent the population as a whole. In response to this critique, research on social mobility expanded to incorporate factors that explain not only general indicators of mobility, but also the reasons for differences in individual opportunities, bringing attention to sex inequalities that remain central to sustainable development agendas.

A further refinement was introduced in the Wisconsin model [

21], which examined the relative influence of family history and education on subsequent educational and occupational achievements. This perspective emphasized both social and psychological factors, including aspirations and motivation, together with the social and economic circumstances of the family that shape the outcomes of children. The Wisconsin model investigated the “mediating mechanisms” through which family history affects individual educational attainment and occupational status. In addition, it highlighted the importance of additional influences, such as peers and teachers, which significantly affect the educational and occupational outcomes of students. Subsequent research has shown that both parents and peers contribute to the formation of students’ ambitions and attitudes toward learning, factors that are critical for later educational and occupational success. Such mechanisms are especially relevant in societies that undergo transition, where aspirations, role models, and institutional support can determine whether young people overcome structural barriers to achieve upward mobility.

By integrating the findings of Blau and Duncan [

8], Sewell and Haller [

21], and subsequent studies, scholars have argued that the influence of family background on occupational status has diminished over time. Both strands of research converge on the conclusion that parental status exerts a significant impact on early occupational attainment, but that education contributes an even greater additional effect. Once educational attainment is taken into account, the remaining effect of parental status on occupational outcomes becomes negligible. In particular, both directions of research employ the same core variables—parental status (occupation), education, and individual occupational attainment—which are also used in the present study. This underscores the dual role of education as both a determinant of individual mobility and a structural condition necessary to achieve inclusive and sustainable development.

Thus, it can be asserted that research on social mobility has contributed substantially to understanding how family-related social and economic circumstances shape educational and occupational achievements. In most studies, socioeconomic status is operationalized as fathers’ education and occupation, or as a composite measure incorporating these and other family characteristics. Some researchers have modified this model due to data limitations or local contextual factors, but the core variables have remained consistent. In this study, the framework is adapted to include maternal characteristics, addressing a gap in Lithuanian research, and link intergenerational mobility more directly to policies that promote sustainable development and intergenerational equity. The main status attainment models, their mechanisms, and their relevance for sustainable development and the Lithuanian case are summarized in

Table 1.

These theoretical insights provide the foundation for the empirical analysis presented in the following section, which applies the status attainment framework to the Lithuanian case.

3. Research Data and Methods

Empirical analysis draws on data from the European Social Survey (ESS) 2020 Round 10 [

14], applying statistical techniques to examine the impact of independent variables on dependent outcomes and thus address research questions. Following previous studies on social mobility [

8], the dependent variables are defined as the highest level of educational attainment and the occupation of the respondents, while the independent variables include the education and occupation of the parents, as well as the gender of the respondents.

The Lithuanian ESS sample included 1643 respondents (38.5% men and 61.5% women) aged 15–85. To ensure comparability across cohorts, respondents younger than 30 were excluded, as most had not yet completed their education or established stable careers. The final analytical sample comprised 1412 respondents aged 30 and above (36.8% men and 63.2% women) and those who provided complete information about their educational and occupational achievements. By this age, the majority had completed their highest level of education and entered the labor market, making it possible to assess long-term educational and occupational outcomes.

Occupations were categorized according to the ISCO-08 classification, while parental occupations were grouped into three categories: unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled. Education was recoded into four ISCED-based groups: no/primary, lower secondary, upper secondary/vocational, and higher education. This classification of occupation and education was chosen because the available data did not meet the conditions required for the regression model. This classification was also chosen based on references to ISCO-08 and ISCED, which provide clear skill requirements for specific levels of classification. In addition, this restructuring simplified the analysis and improved comparability between generations.

Three analytical methods were applied. First, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribution of education and occupation between generations, disaggregating the results by gender and age. Second, correlation analysis (Spearman’s rank coefficient) was used to assess the relationships between parents’ education and children’s occupation, following the Blau and Duncan [

8] model. The correlations were interpreted using standard thresholds. Finally, ordinal logistic regression analysis was applied to evaluate the extent to which parental characteristics and respondents’ gender predict educational and occupational attainment.

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27, with Microsoft Excel 2019 used for data management.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The data reveal significant generational differences in education and occupation, reflecting broader patterns of social mobility in Lithuania. By age group, the largest cohorts of respondents were those aged 50–59 years (n = 313) and 60–69 years (n = 300), while the smallest group comprised respondents aged 80 and above (n = 99) (see

Table 2).

Occupational patterns also demonstrate strong intergenerational differences. Among the respondents, the largest share was employed as managers and senior officials (20.4%), service and sales workers (15.5%), agricultural workers (14.1%), and highly skilled professionals (12.1%). Analyzing the distribution of occupations among fathers, it was observed that the majority were medium-skilled workers (20.3%), agricultural workers (19%), and highly skilled manual workers (12.7%). The contrast is particularly sharp in managerial roles: 20.4% of respondents compared with only 3.4% of fathers, and similarly for service occupations (15.5% versus 3.65%). Conversely, fathers outnumbered children by nearly tenfold in highly skilled manual work. Mothers’ occupations showed different patterns: only 1.3% held managerial positions, compared to 20.4% of their children. Yet mothers were more often employed in clerical and professional positions than fathers. The largest disparity occurred in managerial roles, where children outnumbered mothers by a factor of fifteen (see

Table 3).

Descriptive analysis suggests that children surpass their parents, as parents predominantly occupy lower levels of education, while children are concentrated in higher levels. This confirms the prevalence of vertical, upward intergenerational mobility trends in Lithuanian society. The difference can be explained by structural social mobility, driven by changes in the Lithuanian education system (such as the introduction of compulsory preschool education) and by greater demand for and supply of a more qualified workforce. This transformation was influenced by the country’s historical past and the collapse of the Soviet Union, which prompted both the market and society as a whole to transition to a market economy and adapt to globalization. It can be emphasized that structural social mobility also prevails, stimulated by Lithuania’s path toward European Union accession and its efforts to meet progress-oriented criteria. The reduced influence of the state (following the collapse of the Soviet Union) and the incentives to create a modern, industrial welfare state based on a market economy have encouraged comprehensive national development and natural social changes in terms of both education and occupation.

It is crucial to note that previous studies of Lithuanian society indicate that education is one of the main factors influencing social mobility processes, although its importance varies considerably between generations [

12,

13]. Individuals with higher levels of education and greater social capital tend to gain access to employment more easily and contribute to economic growth, which can be directed toward welfare-state objectives. Education is also strongly associated with improved health, longer life expectancy, and intergenerational benefits, as children of educated parents aspire to higher academic and life goals. Empirical evidence also shows that reducing poverty mitigates its negative effects on well-being, such as stress caused by deprivation [

22].

In terms of sustainable development, education plays a dual role: it increases individual productivity—returns to schooling range from 9% to 27% per additional year [

23]—and fosters ecological awareness and sustainable practices. Social capital, particularly “bridging ties” that connect individuals across socioeconomic divides, is a key determinant of long-term upward mobility [

24]. Greater social mobility not only alleviates poverty but also enhances resilience to systemic shocks, aligning with the UN’s 2030 Agenda [

25]. Taken together, expanding equitable access to education and strengthening social capital are crucial for promoting well-being, reducing inequality, and advancing sustainable development. This confirms that effective social policy interventions expand opportunities to attain higher education, develop individual talents, and accumulate human capital [

26], which in turn influences social mobility.

When analyzing social mobility theoretically, considerable attention is paid not only to education but also to individuals’ occupations. It has been observed that respondents are less likely to occupy lower-skilled positions (except for civil servants) compared to their parents. This means that in families where parents worked in these fields, children were socially mobile, achieving professional statuses recognized as more skilled. These results highlight that Lithuanian society is facing a decline in agricultural employment, paralleled by the development of the industrial and service sectors. This undoubtedly promotes structural social mobility through the increasing demand for a more qualified workforce, facilitated by the education system. Attaining higher education is becoming a prerequisite for adapting to the changing labor market, which is shaped by labor demand and influences career choices.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

This study is based on the traditional Blau and Duncan (1967) [

8] model of status attainment, which emphasizes correlations between key variables such as the highest level of education and the occupational status of both parents and their children. In response to critiques regarding the omission of the socioeconomic background of mothers in similar research, the model has been refined to incorporate maternal characteristics and to include the gender of the children as a variable. These modifications also contribute to addressing the broader research gap on social mobility in Lithuania and comparable contexts. To this end, the Blau and Duncan [

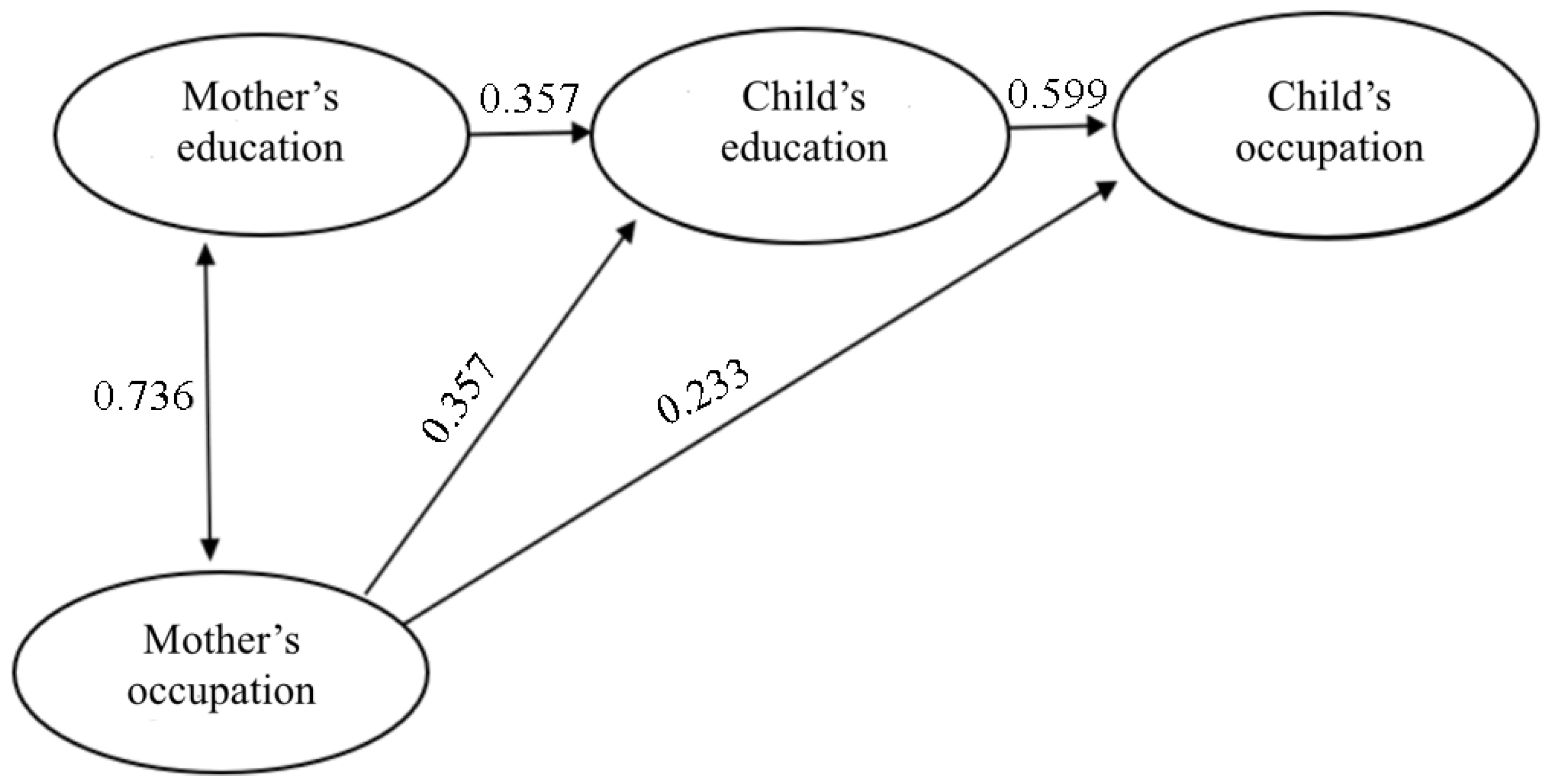

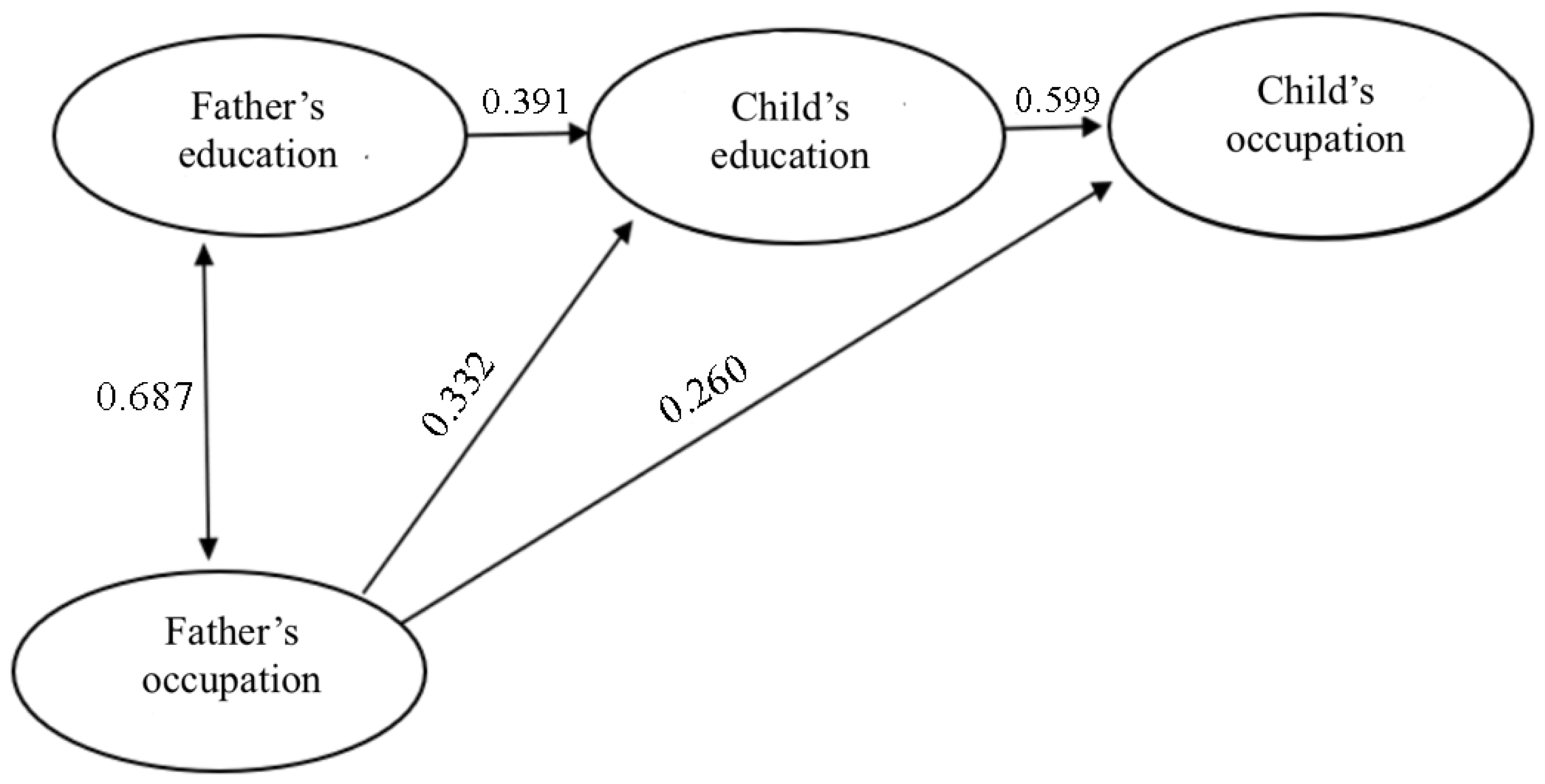

8] status-attainment framework was applied to assess the strength and direction of these relationships, which are crucial for interpreting intergenerational mobility patterns. Both maternal and paternal models include the education and occupation of the parents (measured when the respondent was 14 years old), the highest educational attainment of the respondents, and their current occupation. All correlations were found to be statistically significant (

p < 0.05).

The analysis reveals that the relationship between parents’ education and children’s occupation is significant and has a considerable influence on children’s life outcomes. Parental education, including that of both fathers and mothers, exerts a positive influence on children’s educational attainment. Although the correlations are relatively weak (

Appendix A,

Figure A1 and

Figure A2), they indicate that parental socioeconomic status explains almost 30% of the variation in children’s trajectories, influencing both education and occupation.

The moderate correlation between the highest education of the respondents and their current occupation confirms that education strongly predicts occupational status. Furthermore, moderate to strong correlations were observed between both parents’ occupation and education. Interestingly, parental education appears to have had a stronger impact on their own career outcomes than on those of their children, suggesting a generational shift in the role of education.

The main findings indicate that the weakest positive correlation occurs between the occupation of mothers and the occupation of their children, suggesting that the occupational level of the mother has the least influence on the child’s future career. By contrast, the strongest correlation exists between the education and occupation of the respondents, confirming that education is the most powerful driver of occupational attainment. In addition, strong positive correlations are evident between parental education and their own occupation, highlighting that education—both for parents and children—remains the key determinant of occupational status across generations.

4.3. Logistic Regression Analysis

To examine the main factors shaping intergenerational mobility, two ordinal logistic regression models were developed. Both models included the education and occupation of the respondents as dependent variables, with the education and occupation of the parents, the respondents’ gender, and the interaction terms as independent variables.

It should be emphasized that only the final specifications of the models are presented. Prior to their development, a series of preliminary models were estimated, many of which yielded statistically insignificant results. Consequently, several variables (such as fathers’ characteristics) were excluded because their inclusion rendered the model statistically insignificant. Through this iterative process, a statistically significant model was obtained. Given that the theoretical analysis indicated that sociological research predominantly emphasizes educational and occupational outcomes, this study likewise focuses on these variables.

The first model, with education as the dependent variable, initially showed limited explanatory power, with only parental education emerging as statistically significant. However, when interaction terms were introduced, the model improved (

p < 0.05; Nagelkerke R

2 = 0.473) (

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

Table A2). The results revealed that the combined effect of parental education has a positive and significant influence on the educational attainment of children. This confirms that educated parents are better positioned to transfer social, cultural, and financial capital to their children, providing favorable conditions for skill development, access to quality schools, and extracurricular resources (

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

Table A2).

By contrast, as both models indicate, maternal occupational status shows a negative association with children’s education when considered in isolation. An increase in the occupational level of the mother does not automatically lead to a higher educational attainment of the child unless reinforced by the father’s education (

Appendix A,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4). This pattern is particularly notable in Lithuania, where high divorce rates and gender inequalities often constrain women’s ability to invest in children’s education. Persistent occupational segregation (“glass walls”) places women in less prestigious and flexible sectors such as health care, social work, and education, while there is a significant gender pay gap (exceeding 30% in several sectors) reduces women’s long-term financial security. These disparities are especially relevant in single-parent households, where resources to invest in education are limited. Time poverty further compounds the problem: Lithuanian women spend more hours than men in both paid and unpaid work, leaving less time for direct child-rearing.

The second model, with occupation as the dependent variable, confirmed the centrality of the respondents’ own education. The model demonstrated acceptable explanatory power (Nagelkerke R

2 = 0.341), with only fathers’ occupation and the respondents’ education emerging as statistically significant predictors. After refinement, parental occupation and interaction effects were excluded, while the combined effect of parental education remained a weak but significant predictor (

Appendix A,

Table A3 and

Table A4). Crucially, the respondents’ own education was the strongest determinant of occupational achievement, while the gender variables in both first and second models (

Appendix A,

Table A3 and

Table A4) indicated that men (the value with a minus) may face greater barriers to upward mobility than women.

Taking into account the results of the first and second models, it is important to expand the gender aspect. An analysis of gender differences shows that men are significantly less likely to attain higher education compared to women, a finding consistent with national higher education trends. Women dominate the tertiary and postgraduate levels, while men predominate in lower levels of education [

27]. Economic explanations suggest that men without higher education historically accessed relatively well-paid manual jobs, reducing incentives to pursue further study, while sociological perspectives point to role-model effects: children identify strongly with the same-gender parent as boys raised by single mothers are therefore especially disadvantaged [

17,

20,

22,

26]. Consequently, boys in single-parent households (predominantly headed by mothers in Lithuania) face higher educational disadvantages than girls. Rising divorce rates and the prevalence of single-parent families may therefore generate gender-differentiated outcomes, a pattern corroborated by Hetherington [

22], who finds that boys are more negatively affected than girls by single-parent upbringing.

These results must be interpreted within the historical context of Lithuania. Respondents aged 30–49 years were born in the Soviet era, but built their educational and occupational careers during independence, benefiting from democratization, EU integration, and labor market modernization. Older cohorts, on the contrary, were constrained by Soviet-era conditions of centralized planning and restricted access to higher education, where opportunities largely reflected state priorities rather than individual aspirations. Following Lithuania’s independence, post-Soviet reforms—including EU accession, the expansion of compulsory pre-primary education, and other progressive measures—reshaped opportunities by reducing state control and strengthening welfare systems aligned with both personal aspirations and market principles.

In general, the limited differences observed in parental education and occupation suggest that intergenerational disparities were shaped more by structural constraints and historical legacy than by individual capacity. These patterns reflect structural mobility [

21], driven by broad social transformations, while the respondents’ own education remains the decisive factor in achieving upward mobility.

5. Discussion

The analysis across all stages of this study revealed that Lithuanian respondents attain not only higher levels of education but also a higher occupational status compared to their parents. This confirms the persistence of upward structural mobility in Lithuanian society. Comparable educational and occupational outcomes were observed between mothers and fathers, and the correlation analysis highlighted the strong association between parental socioeconomic circumstances and children’s achievements. A higher socioeconomic status of parents positively influences individual outcomes, improving both educational and occupational attainment. However, parental education exerts a stronger effect on the parents’ own occupational status than on their children’s, with the father–child education link slightly stronger than the equivalent mother–child link. By contrast, the weakest association was observed between parental and child occupations—a finding also confirmed by the regression analysis. Despite the substantial role of education in shaping outcomes, its influence across generations appears to weaken, suggesting that education alone cannot guarantee occupational advancement.

In line with this, Vencius [

12,

13] demonstrates that upward mobility is constrained by the diminishing role of education, implying that higher attainment does not always translate into improved social standing. These findings are consistent with Blau and Duncan’s [

8] status attainment model and subsequent studies [

28], which emphasize parental education as a key determinant influencing children’s achievements and intergenerational mobility.

Descriptive statistics also show pronounced generational differences. Fathers are concentrated at lower educational levels, while children more often hold higher qualifications, except for vocational education, where distributions are similar. This divergence reflects the structural mobility shaped by reforms in Lithuania’s educational system, which expanded from primary schooling to compulsory secondary education. In 1975, universal secondary education was implemented and in 1986–1987, the transition was made to 12 years of secondary education and four years of primary education for children aged 6–10 years. In addition, Soviet-era reforms introduced vocational and technical pathways alongside higher education institutions. These reforms illustrate the role of state-led policies in creating favorable conditions for younger cohorts to pursue higher education. Education must therefore be considered a central—but not exclusive—factor in social mobility.

The regression analysis confirms the decisive role of education in career achievement. Education significantly increases the likelihood of achieving a higher occupational status, and this effect is reinforced when both parents have higher levels of education. At the same time, the analysis revealed that the occupational status of mothers can negatively affect the outcomes of children when not supported by the education of fathers. This suggests that uneven intergenerational transmission of educational resources, combined with gender inequalities, may constrain children’s career achievements.

Together, descriptive, correlation, and regression analyses highlight intergenerational differences in both education and occupation. These results underscore the prevalence of vertical upward social mobility, shaped not only by individual characteristics but also by the broader historical transformations of Lithuania. Beyond the national context, the study demonstrates the broader significance of social mobility as a catalyst for sustainable development. Educational attainment is essential in shaping occupational trajectories, as the quantitative analysis revealed—higher levels of education substantially improve the chances of upward occupational attainment. Ensuring equitable access to education is, therefore, not only a matter of personal advancement but also a prerequisite for achieving sustainable development objectives. Higher education fosters human capital, enhances employability, and contributes to economic growth, while reducing structural inequalities.

The observed influence of parental education—particularly the interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ levels—highlights the intergenerational dimension of inequality. Addressing these disparities aligns directly with social policy objectives, that emphasize inclusive and equitable education for all. Targeted social policies that mitigate the effect of socioeconomic background on educational outcomes are essential for breaking cycles of disadvantage. The analysis underscores the need for policies that promote equal pay, support work–life balance, and reduce occupational segregation. Ensuring equal opportunities in education and employment, particularly for vulnerable groups such as women, not only strengthens households and communities, but also reinforces the social foundations of sustainable development.

Although education strongly predicts occupational attainment, the findings confirm that higher education alone does not automatically guarantee higher wages or higher-status positions. The value of education depends on broader labor market dynamics, including demand for specific qualifications, occupational segregation, and structural inequalities. This suggests that education must be complemented by inclusive labor market structures and employer recognition of skills. Effective policy measures are therefore needed to better align educational outcomes with labor market needs, ensure fair pay, and reduce barriers that prevent educational achievements from translating into upward social mobility.

In summary, the findings highlight the importance of integrated social policy measures that connect education, labor market structures, and gender equality. By addressing the mechanisms through which inequalities are reproduced across generations, policymakers can foster inclusive growth and long-term resilience. Social mobility is therefore not only an individual achievement but also a core pillar of sustainable development. Within this framework, the SDGs emphasize mobility as both a means of breaking cycles of disadvantage and as an indicator of more equitable societies. The UN SDGs Report [

25] underscores that innovative governance—through stronger institutions, inclusive policies, and effective inequality reduction—is essential to achieve this progress.

Based on the Lithuanian case, several policy directions are proposed:

Ensure equitable access to quality education—particularly state-funded secondary and higher education—to reduce achievement disparities and support upward social mobility (central government).

Expand early childhood and after-school programs, including tutoring and digital/AI-based mentorship, with priority given to children from single-parent or socio-economically disadvantaged households (regional government).

Reform higher education admissions by incorporating applicants’ motivation and socio-economic background alongside standardized examinations (central government).

Promote multi-level cooperation between businesses and central/regional authorities to align human resource development with national and regional labor market needs (central and regional government).

Support work–family balance through subsidized childcare, flexible schedules, remote work options, and part-time employment, particularly for single parents (central and regional government).

Strengthen family financial support through increased child allowances, tax incentives, and social insurance relief to mitigate intergenerational disadvantage (central and regional government).

Reduce gender pay disparities by monitoring, regulating, and equalizing wage systems across the public and private sectors (central and regional government).

Expand active labor market policies and retraining opportunities to facilitate transitions to higher-skilled and sustainable occupations (central and regional government)

Encourage entrepreneurialism and access to networks for underrepresented groups to improve occupational mobility (central and regional government).

Using the SDGs as both a means and an indicator of social mobility provides an opportunity to address structural inequalities holistically. Long-term success depends on strengthening educational and family systems, fostering innovative governance, and ensuring inclusive participation, so that social and environmental objectives are mutually reinforced.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that Lithuania has undergone notable upward intergenerational mobility, with respondents attaining higher levels of education and occupational status than their parents. Education remains the central driver of occupational achievement, but its effect across generations appears to be weakening, indicating that higher education alone no longer guarantees career advancement. Parental education—particularly the combined influence of both parents—continues to shape outcomes, whereas maternal occupation has a more limited effect. Gender disparities also persist, as men are less likely to achieve higher education compared to women, highlighting structural inequalities that remain embedded in the system.

In this study, two hypotheses were formulated. The first hypothesis stated that an individual’s education is primarily determined by the educational attainment of the father and his occupational status. However, the analysis showed that the father’s occupation was not a significant predictor of educational or occupational outcomes. Parental education proved relevant only when interacting with the mother’s education. Consequently, the first hypothesis was not supported. The second hypothesis posited that the interaction between the education of mothers and fathers exerts a significant influence on an individual’s occupational achievements. Quantitative analyses revealed that parental educational interaction was a statistically significant factor in both the educational and occupational regression models. In the case of education, this variable exerted a stronger effect than in the occupational model, where the individual’s own educational attainment emerged as the dominant predictor. Therefore, the second hypothesis received only partial empirical support.

These findings align with theoretical insights from Blau and Duncan’s [

8] status-attainment model and its later refinements, which emphasize the decisive role of education as a mediator of social mobility. At the same time, Lithuania’s trajectory illustrates how large-scale structural transformations—such as post-Soviet reforms and EU integration—have created conditions for generational progress.

In general, the results highlight that equitable access to quality education, gender equality, and inclusive labor markets are crucial for strengthening social mobility as a foundation for sustainable development.

This article has several limitations. First, it focuses on a single-country case and is constrained by both data availability and reliance on a specific time period. Second, the analysis focuses on educational and occupational attainment without explicitly addressing labor market dynamics or the extent to which employers reward particular qualifications. Future research should therefore employ longitudinal data, extend to cross-country comparisons, and incorporate additional variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how social mobility contributes to long-term societal resilience and sustainable development. In particular, further studies should examine the interaction between educational attainment and labor market demand, identifying which qualifications are most valued by employers and how these factors shape mobility outcomes.