Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Carriers Preparation

2.3. Determination of Textural and Morphology Properties of Untreated SCG and SCG-Derived Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carriers

2.4. Immobilization

2.5. Biochemical and Operational Characterization of Lipases

2.6. Immobilized Lipase Functionality Testing

2.6.1. Wastewater Pretreatment

2.6.2. Cocoa Butter Substitute Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Textural Properties of SCG-Derived Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carrier

3.2. Morphology of SCG-Derived Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carrier

3.3. Immobilization of Lipases

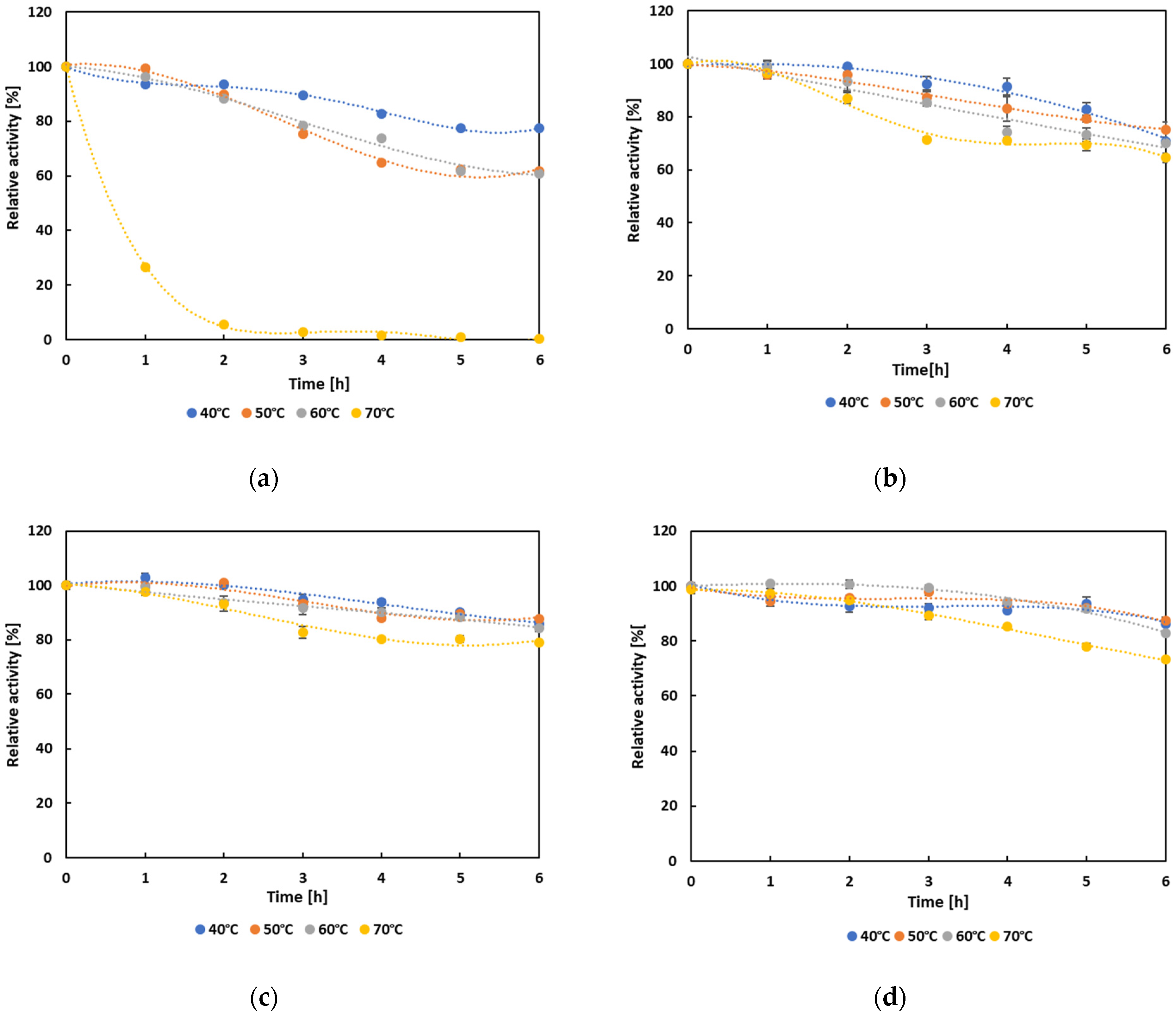

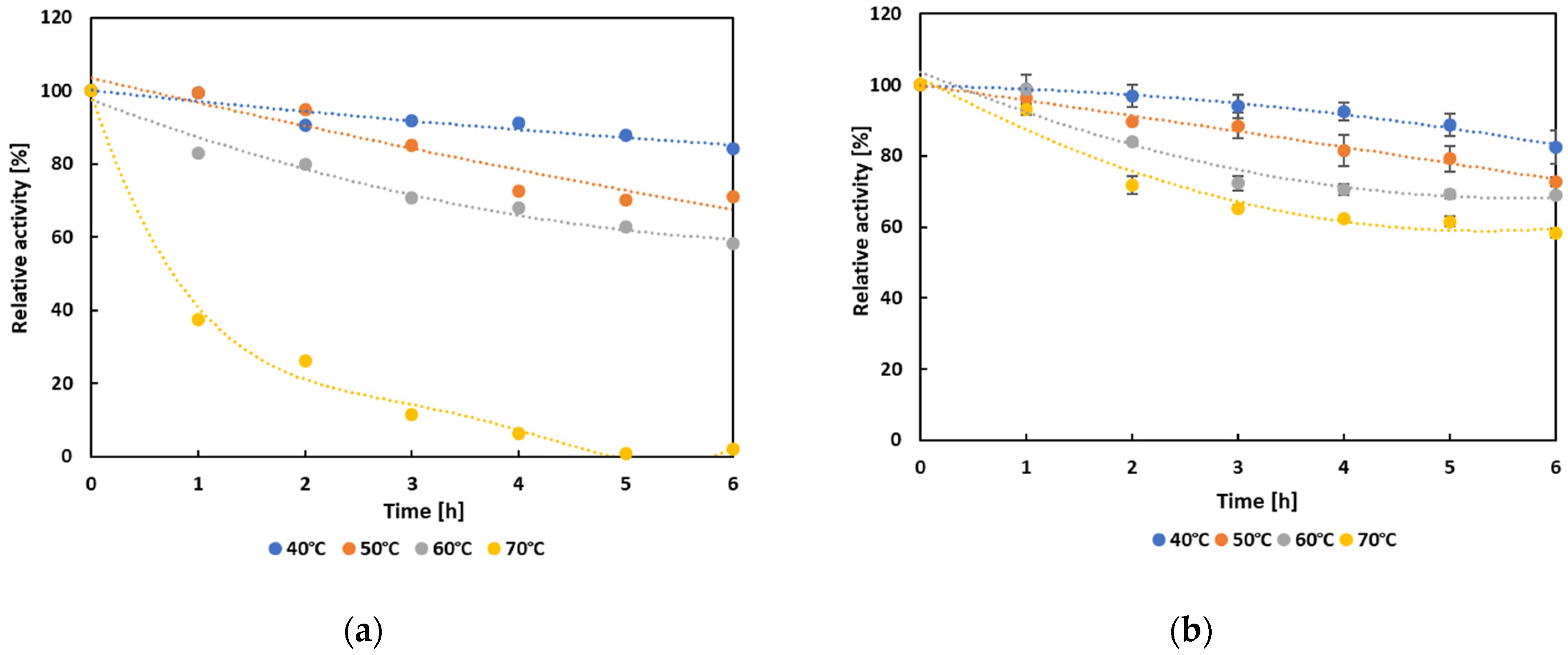

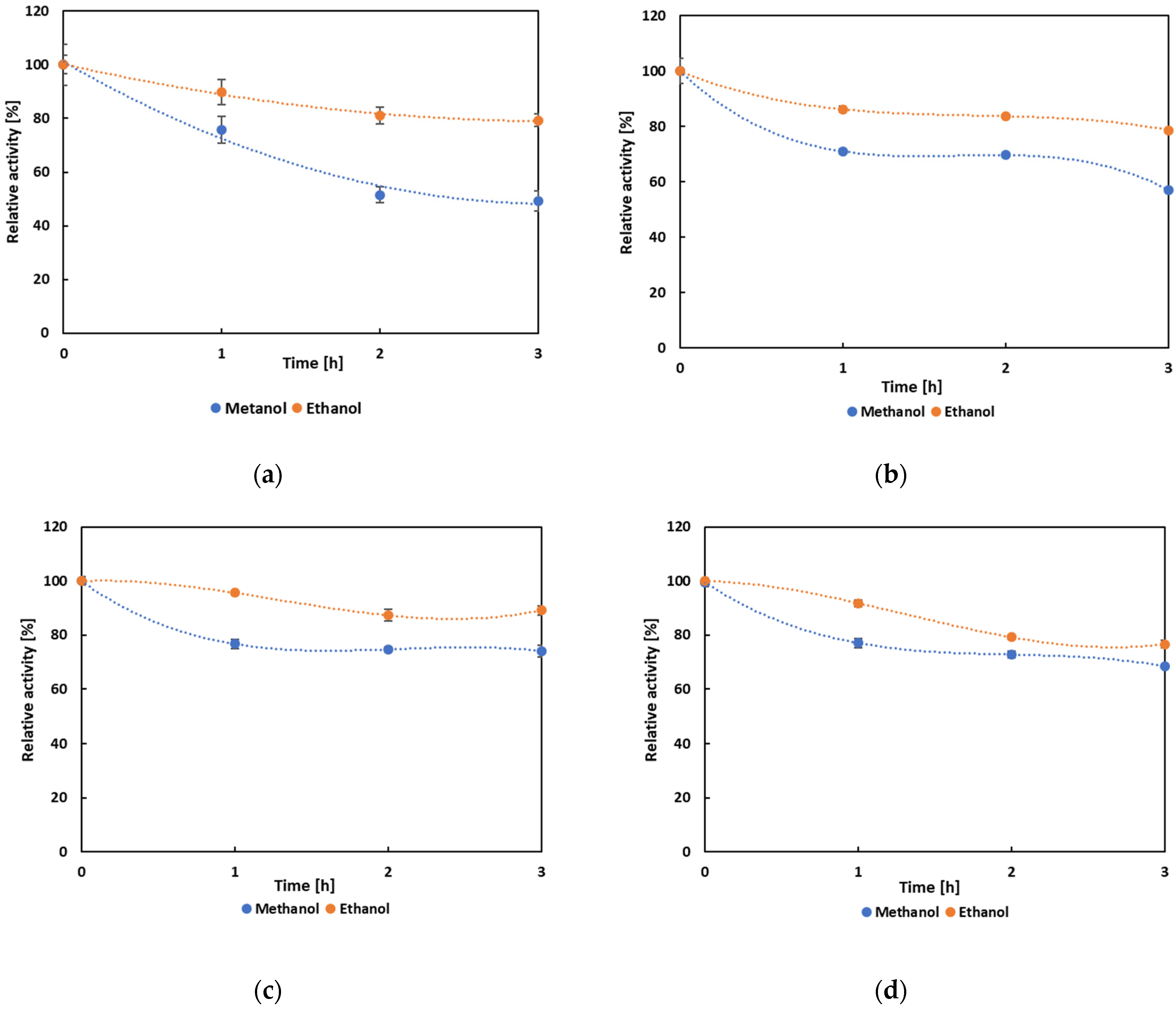

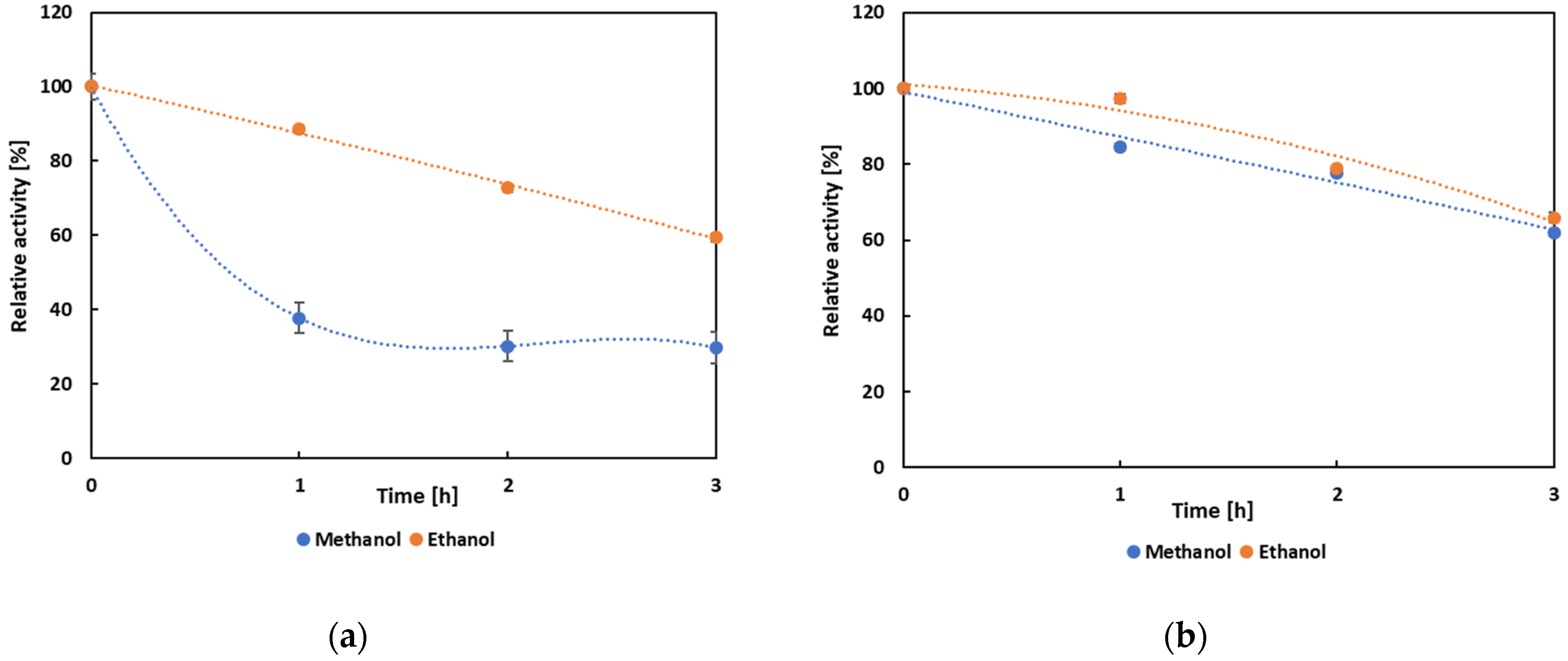

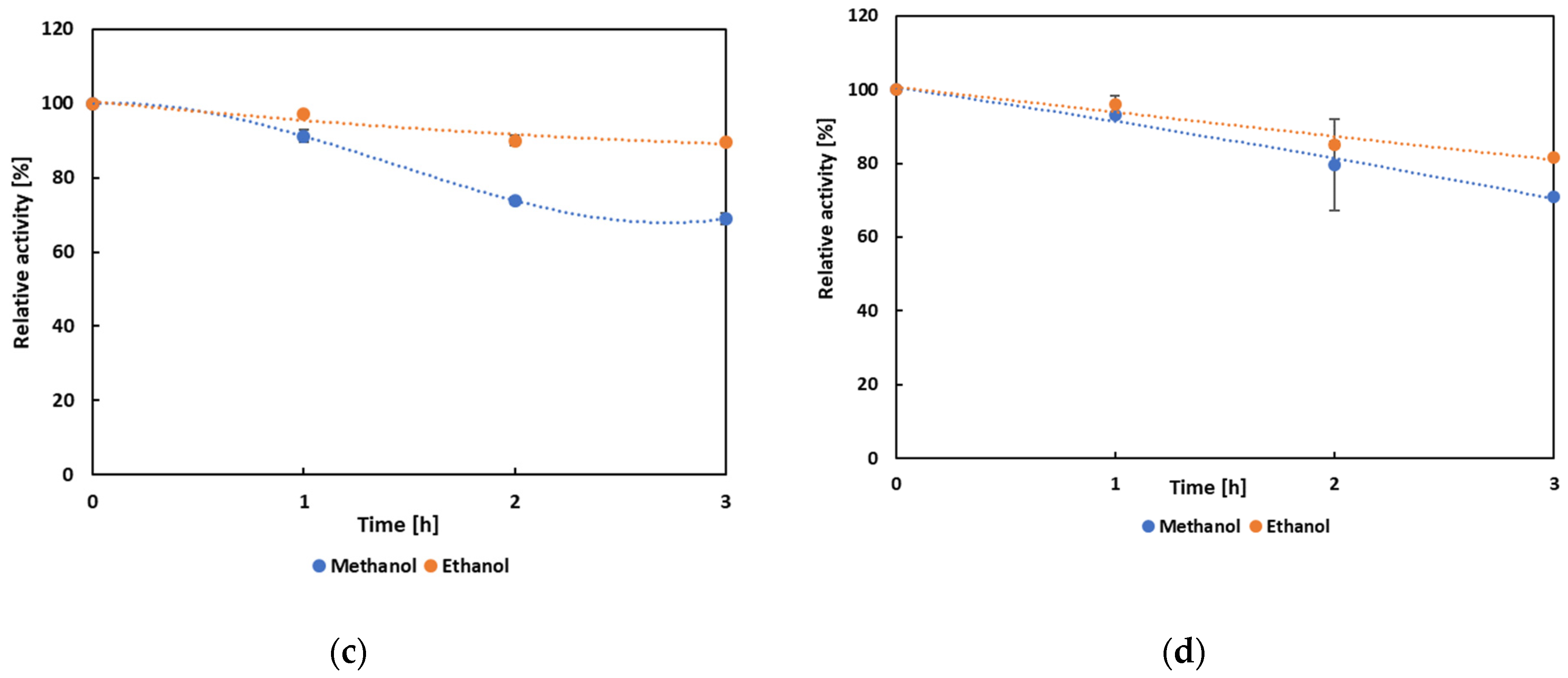

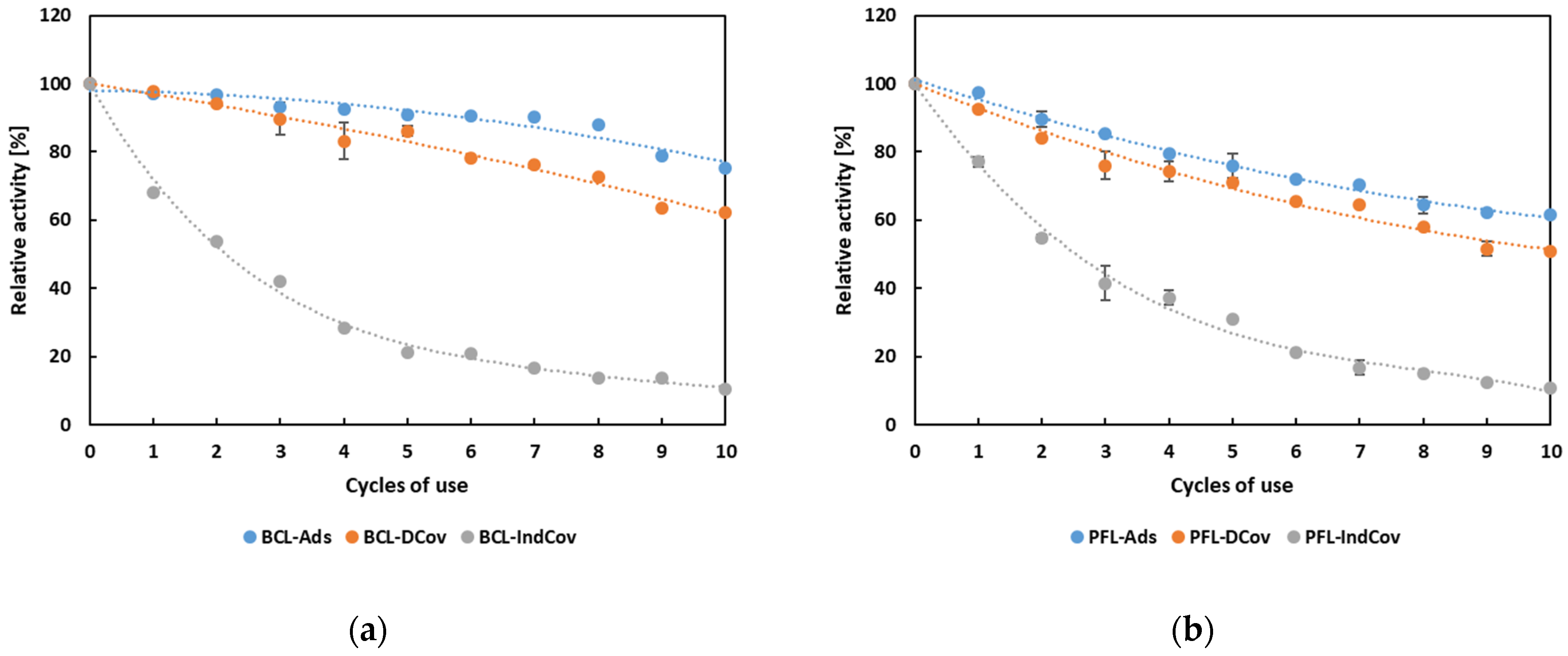

3.4. Biochemical Characterization and Operational Properties of Selected Lipases

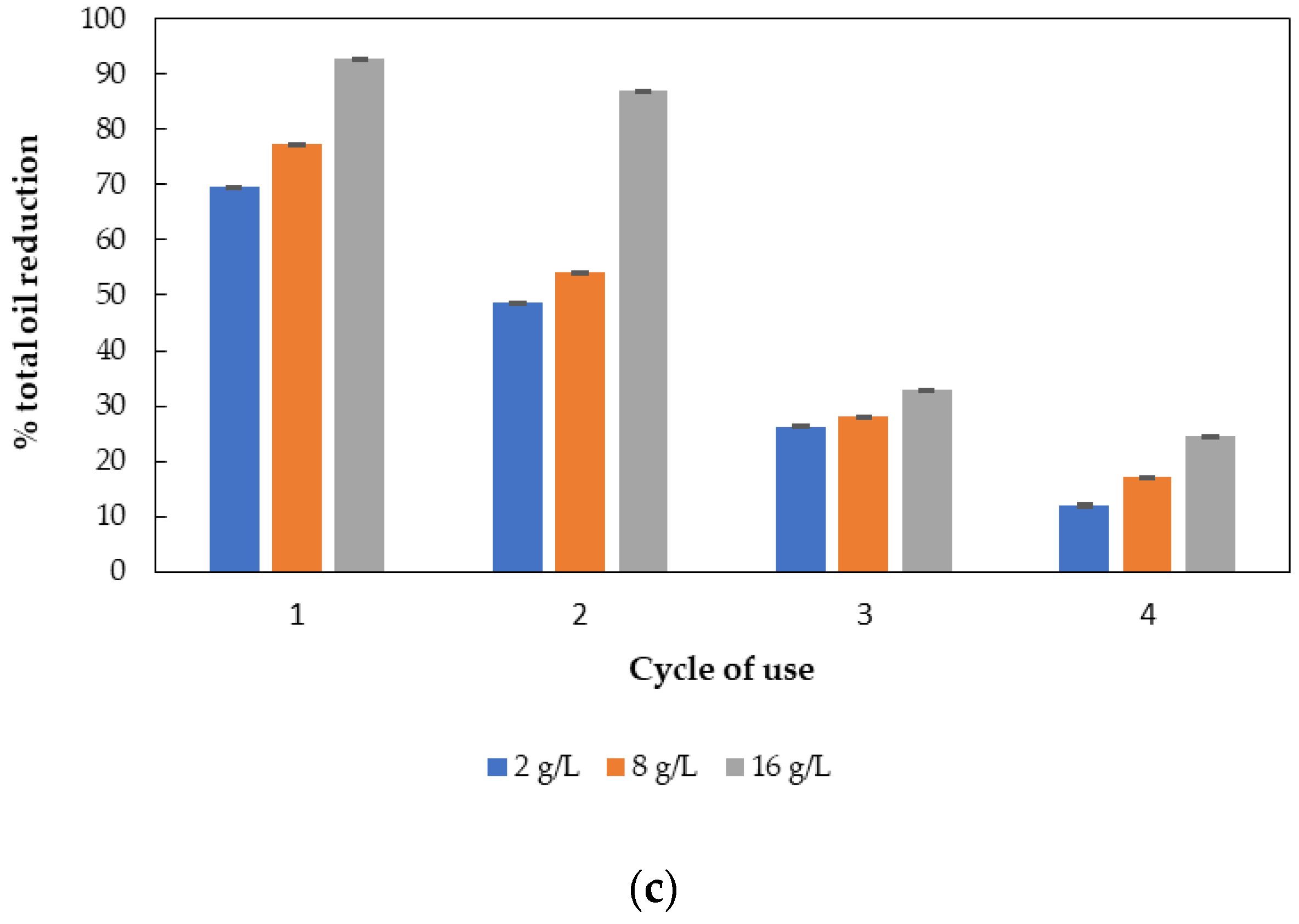

3.5. Wastewater Pretreatment

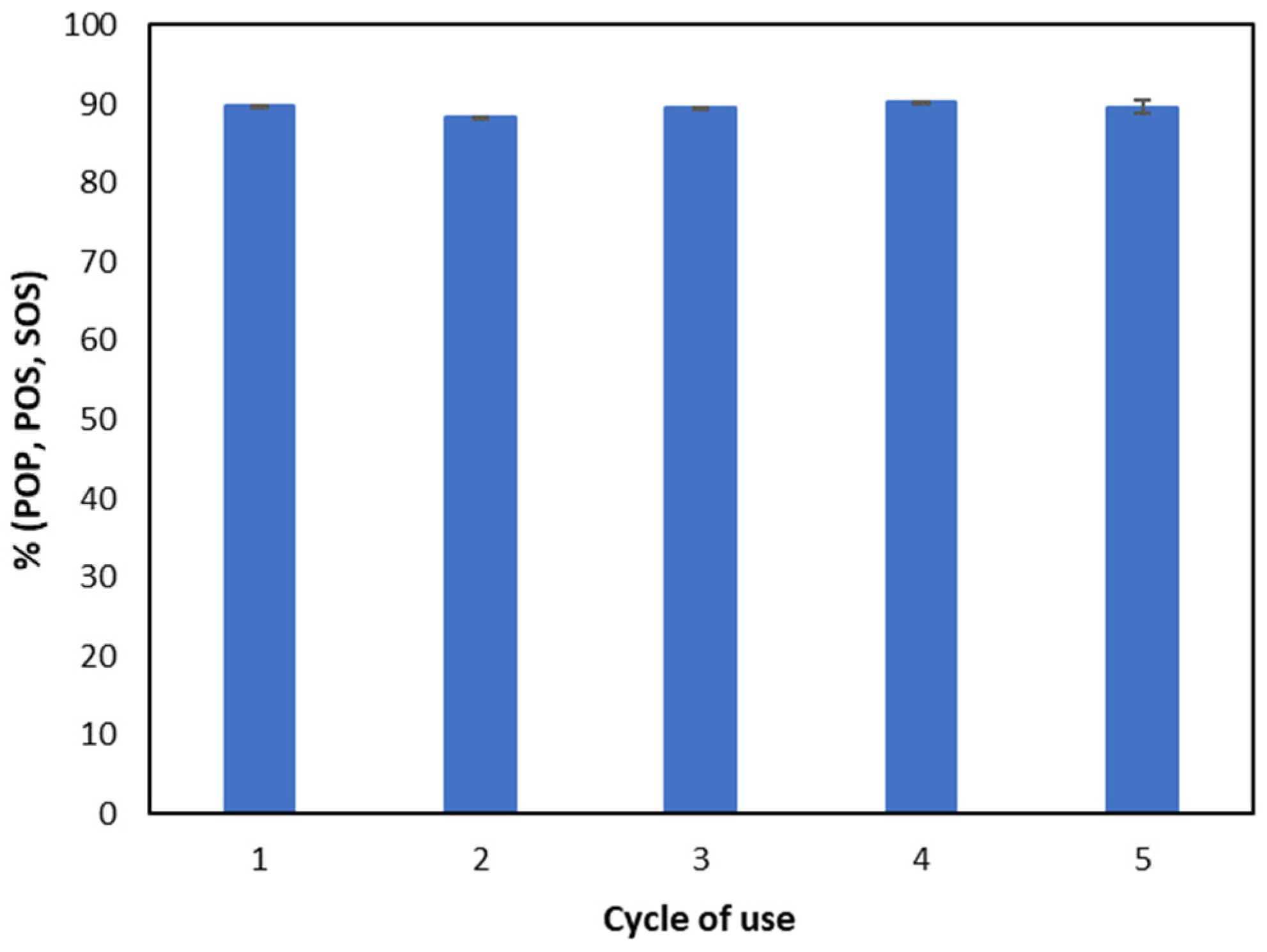

3.6. Cocoa Butter Substitute Syntnesis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCG | Spent Coffee Grounds |

| BCL | Burkholderia cepacia lipase |

| PFL | Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase |

| Ads | Immobilization by adsorption |

| DCov | Immobilization by direct covalent binding |

| IndCov | Immobilization by indirect covalent binding |

| CBS | Cococa butter substitute |

| POP | 1,3-dipalmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycerol |

| POS | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3-stearoyl-glycerol |

| SOS | 1,3-distearoyl-2-oleoyl-glycerol |

| pNPP | p-nitrophenyl palmitate |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method |

| BJH | Barrett-Joyner-Halenda method |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

References

- Pascucci, F. The State of the Global Coffee Sector. In Sustainability in the Coffee Supply Chain: Tensions and Paradoxes; Pascucci, F., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 57–75. ISBN 978-3-031-72502-9. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Vergara-Castañeda, H.A.; Oomah, B.D. Spent Coffee Grounds: A Review on Current Research and Future Prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.; Cardoso, M.M.; Fernandes, L.; Oliveira, M.; Mendes, E.; Baptista, P.; Morais, S.; Casal, S. Espresso Coffee Residues: A Valuable Source of Unextracted Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7777–7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNutt, J.; He, Q. Spent Coffee Grounds: A Review on Current Utilization. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janissen, B.; Huynh, T. Chemical Composition and Value-Adding Applications of Coffee Industry by-Products: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, A.T.; Chun, B.S. Influence of Pretreatment and Modifiers on Subcritical Water Liquefaction of Spent Coffee Grounds: A Green Waste Valorization Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3719–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekalo, M.; Rajs, B.B.; Aladić, K.; Jakobek, L.; Šereš, Z.; Krstović, S.; Jokić, S.; Budžaki, S.; Strelec, I. Multistep Extraction Transformation of Spent Coffee Grounds to the Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carrier. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Nunes, F.M.; Domingues, M.R.; Coimbra, M.A. Extractability and Structure of Spent Coffee Ground Polysaccharides by Roasting Pre-Treatments. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 97, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, C.P.; Coimbra, M.A. Microwave Superheated Water Extraction of Polysaccharides from Spent Coffee Grounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-Y.; Muruganantham, R.; Tai, S.-H.; Chang, B.K.; Wu, S.-C.; Chueh, Y.-L.; Liu, W.-R. Coffee Grounds-Derived Carbon as High Performance Anode Materials for Energy Storage Applications. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Chemical, Functional, and Structural Properties of Spent Coffee Grounds and Coffee Silverskin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.; van Pelt, S. Enzyme Immobilisation in Biocatalysis: Why, What and How. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6223–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, C.; Palomo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Improvement of Enzyme Activity, Stability and Selectivity via Immobilization Techniques. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, A.; Serban, S. Industrial Applications of Immobilized Enzymes—A Review. Mol. Catal. 2019, 479, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavlinskaya, M.S.; Sorokin, A.V.; Holyavka, M.G.; Zuev, Y.F.; Artyukhov, V.G. Cellulose and Cellulose-Based Materials for Enzyme Immobilization: A Review. Biophys. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Martínez, E.F.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Levin, L.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Lignocellulosic Residues as Supports for Enzyme Immobilization, and Biocatalysts with Potential Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, K.-E.; Eggert, T. Lipases for Biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.; Gupta, M.N. Lipase Promiscuity and Its Biochemical Applications. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Shah, A.A.; Hameed, A. Industrial Applications of Microbial Lipases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006, 39, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P.; Enespa; Singh, R.; Arora, P.K. Microbial Lipases and Their Industrial Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.S.; Fernandes de Melo Neta, M.M.; Sales, M.B.; Silva de Oliveira, F.A.; de Castro Bizerra, V.; Sanders Lopes, A.A.; de Sousa Rios, M.A.; Santos, J.C.S.d. Research Progress and Trends on Utilization of Lignocellulosic Residues as Supports for Enzyme Immobilization via Advanced Bibliometric Analysis. Polymers 2023, 15, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.B.; Miguez, J.P.; Bolina, I.C.A.; Salviano, A.B.; Gomes, R.A.B.; Tavano, O.L.; Luiz, J.H.H.; Tardioli, P.W.; Cren, É.C.; Mendes, A.A. Preparation, Functionalization and Characterization of Rice Husk Silica for Lipase Immobilization via Adsorption. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2019, 128, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, M.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization: The Role of Artificial Intelligence, Novel Nanomaterials, and Dynamic Carrier Systems. Catalysts 2025, 15, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-J.; Hu, J.-L. Biomass and Circular Economy: Now and the Future. Biomass 2024, 4, 720–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattatraya Saratale, G.; Bhosale, R.; Shobana, S.; Banu, J.R.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Sirohi, R.; Kant Bhatia, S.; Atabani, A.E.; Mulone, V.; et al. A Review on Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds (SCG) towards Biopolymers and Biocatalysts Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 314, 123800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Z.; Yu, T.; Yan, F. Spent Coffee Grounds: Present and Future of Environmentally Friendly Applications on Industries-A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Woodley, J.M.; Fernandez-Laufente, R. Is Enzyme Immobilization a Mature Discipline? Some Critical Considerations to Capitalize on the Benefits of Immobilization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 6251–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Review on Bioconversion of Agro-Industrial Wastes to Industrially Important Enzymes. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budžaki, S.; Velić, N.; Ostojčić, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Rajs, B.B.; Šereš, Z.; Maravić, N.; Stanojev, J.; Hessel, V.; Strelec, I. Waste Management in the Agri-Food Industry: The Conversion of Eggshells, Spent Coffee Grounds, and Brown Onion Skins into Carriers for Lipase Immobilization. Foods 2022, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet-Ragel, K.; López-Pou, L.; Tutusaus, G.; Benaiges, M.D.; Valero, F. Rice Husk Ash as a Potential Carrier for the Immobilization of Lipases Applied in the Enzymatic Production of Biodiesel. Biocatal. Biotransformation 2018, 36, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, A.M.; Chiappini, V.; Amadoro, P. Immobilization of Lipase on Spent Coffee Grounds by Physical and Covalent Methods: A Comparison Study. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 192, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, K.; Zieniuk, B.; Piasek, A.M.; Wysocki, Ł.; Sobiepanek, A.; Fabiszewska, A. Obtaining a Biodegradable Biocatalyst—Study on Lipase Immobilization on Spent Coffee Grounds as Potential Carriers. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 59, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, R.; Sanny, S.A.; Derman, E. Stability Studies of Immobilized Lipase on Rice Husk and Eggshell Membrane. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 206, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.J.P.A.; Marques, M.B.F.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Development of Films from Spent Coffee Grounds’ Polysaccharides Crosslinked with Calcium Ions and 1,4-Phenylenediboronic Acid: A Comparative Analysis of Film Properties and Biodegradability. Foods 2023, 12, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, E.; Cruzat, V.; Singh, I.; Rose’Meyer, R.B.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. The Potential of Spent Coffee Grounds in Functional Food Development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigliobianco, M.R.; Campisi, B.; Vargas Peregrina, D.; Censi, R.; Khamitova, G.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Zannotti, M.; Ferraro, S.; Giovannetti, R.; et al. Optimization of the Extraction from Spent Coffee Grounds Using the Desirability Approach. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmet, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers | Journal of the American Chemical Society. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, B.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J. Interpretation of BJH Method for Calculating Aperture Distribution Process. Univ Chem 2020, 35, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittrat, P.; Chacho, T.; Pholprayoon, J.; Suttiwarayanon, N.; Charoenpanich, J. Application of Agriculture Waste as a Support for Lipase Immobilization. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Tao, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, B.; Tan, T. Improving the Activity and Stability of Yarrowia Lipolytica Lipase Lip2 by Immobilization on Polyethyleneimine-Coated Polyurethane Foam. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 91, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespugli, M.; Lotteria, S.; Navarini, L.; Lonzarich, V.; Del Terra, L.; Vita, F.; Zweyer, M.; Baldini, G.; Ferrario, V.; Ebert, C.; et al. Rice Husk as an Inexpensive Renewable Immobilization Carrier for Biocatalysts Employed in the Food, Cosmetic and Polymer Sectors. Catalysts 2018, 8, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Ni, Y. Sodium Periodate Oxidation of Cellulose Nanocrystal and Its Application as a Paper Wet Strength Additive. Cellulose 2015, 22, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Lai, Q.; Jiang, B. Loofah Sponge Activated by Periodate Oxidation as a Carrier for Covalent Immobilization of Lipase. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustranta, A.; Forssell, P.; Poutanen, K. Applications of Immobilized Lipases to Transesterification and Esterification Reactions in Nonaqueous Systems. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1993, 15, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, D.; Busto, M.D.; Ortega, N. Study of a New Spectrophotometric End-Point Assay for Lipase Activity Determination in Aqueous Media. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, R.; Misra, S.; Rawat, I.; Gupta, P.; Dutt, K.; Parmar, V. Production of 1, 3 Regiospecific Lipase From Bacillus Sp. RK-3: Its Potential to Synthesize Cocoa Butter Substitute. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2011, 7, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutakridsada, P.; Prajaksud, C.; Kuboonya-Aruk, L.; Theerakulpisut, S.; Kamwilaisak, K. Adsorption Characteristics of Activated Carbon Prepared from Spent Ground Coffee. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, N.N.; Tan, V.M.; Trung, D.H.; Huong, P.T.M.; Nhung, L.T.H.; Ha, N.M.; Van, N.T.; Tung, N.T.; Thuy, N.T.T. Effect of Alkaline-Treated Spent Coffee Grounds and Compatibilizer on the Mechanical Properties of Bio-Composite Based on Polypropylene Matrix. Vietnam J. Chem. 2023, 61, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkov, B.; Čermák, J.; Šefara, M.; Janků, J. Pore Classification in the Characterization of Porous Materials: A Perspective. Open Chem. 2007, 5, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.; Bairwan, R.D.; Rizg, W.Y.; Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Murshid, S.S.A.; Sindi, A.M.; Alissa, M.; Saharudin, N.I.; Abdullah, C.K. Enhancement of Spent Coffee Grounds as Biofiller in Biodegradable Polymer Composite for Sustainable Packaging. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 9317–9334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Modifying Enzyme Activity and Selectivity by Immobilization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6290–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, G. da S.; Santana, J.C.C.; Alegre, R.M.; Tambourgi, E.B. Extraction of Lipase from Burkholderia Cepacia by PEG/Phosphate ATPS and Its Biochemical Characterization. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Oikawa, T. Physicochemical Properties of a Lipase from Pseudomonas Fluorescens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1977, 489, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buntić, A.V.; Pavlović, M.D.; Antonović, D.G.; Šiler-Marinković, S.S.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.I. Utilization of Spent Coffee Grounds for Isolation and Stabilization of Paenibacillus Chitinolyticus CKS1 Cellulase by Immobilization. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Galan, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rodrigues, R.C. Potential of Different Enzyme Immobilization Strategies to Improve Enzyme Performance. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2885–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Christena, L.R.; Rajaram, Y.R.S. Enzyme Immobilization: An Overview on Techniques and Support Materials. 3 Biotech 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Strategies for the One-Step Immobilization–Purification of Enzymes as Industrial Biocatalysts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, V.; Conti, C.; Astolfi, M.L.; Girelli, A.M. Characteristic Study of Candida Rugosa Lipase Immobilized on Lignocellulosic Wastes: Effect of Support Material. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 48, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rós, P.C.M.; Silva, G.A.M.; Mendes, A.A.; Santos, J.C.; de Castro, H.F. Evaluation of the Catalytic Properties of Burkholderia Cepacia Lipase Immobilized on Non-Commercial Matrices to Be Used in Biodiesel Synthesis from Different Feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5508–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencreac’h, G.; Leullier, M.; Baratti, J.C. Properties of Free and Immobilized Lipase from Pseudomonas Cepacia. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 56, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojčić, M.; Budžaki, S.; Flanjak, I.; Bilić Rajs, B.; Barišić, I.; Tran, N.N.; Hessel, V.; Strelec, I. Production of Biodiesel by Burkholderia Cepacia Lipase as a Function of Process Parameters. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37, e3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Jiao, L.; Xie, X.; Xu, L.; Yan, J.; Yang, M.; Yan, Y. Characterization of a New Thermostable and Organic Solution-Tolerant Lipase from Pseudomonas Fluorescens and Its Application in the Enrichment of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiCosimo, R.; McAuliffe, J.; Poulose, A.J.; Bohlmann, G. Industrial Use of Immobilized Enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6437–6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, N.R.; Marzuki, N.H.C.; Buang, N.A.; Huyop, F.; Wahab, R.A. An Overview of Technologies for Immobilization of Enzymes and Surface Analysis Techniques for Immobilized Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, P.F.; Finn, R.K. Alcohol Precipitation of Proteins: The Relationship of Denaturation and Precipitation for Catalase. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1981, 23, 2569–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzydlewska, E.; Roszkowska, A.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. A Comparison of Methanol and Ethanol Effects on the Activity and Distribution of Lysosomal Proteases. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 1999, 8, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, I.Y.; Prieto, E.; Jimenez-Junca, C. Ethanol as Additive Enhance the Performance of Immobilized Lipase LipA from Pseudomonas Aeruginosa on Polypropylene Support. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 31, e00659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, S.K.; Srivastava, S.K.; Dutta, N.N.; Garlapati, V.K. Engineering Aspects of Immobilized Lipases on Esterification: A Special Emphasis of Crowding, Confinement and Diffusion Effects. Eng. Life Sci. 2018, 18, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, C.; Saraç, N.; Teke, M.; Uğur, A. A New Bioremediation Method for Removal of Wastewater Containing Oils with High Oleic Acid Composition: Acinetobacter Haemolyticus Lipase Immobilized on Eggshell Membrane with Improved Stabilities. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, P.; Ramani, K.; Sekaran, G. Biocatalytic Approach on the Treatment of Edible Oil Refinery Wastewater. RSC Adv. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, J.; Nakhla, G.; Bassi, A. Hydrolytic Pretreatment of Oily Wastewater by Immobilized Lipase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 145, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.W.; Ahmed Khan, F.S.; Mubarak, N.M.; Karri, R.R.; Khalid, M.; Walvekar, R.; Abdullah, E.C.; Mazari, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Dehghani, M.H. Insight into Immobilization Efficiency of Lipase Enzyme as a Biocatalyst on the Graphene Oxide for Adsorption of Azo Dyes from Industrial Wastewater Effluent. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 354, 118849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Silva, T.; Keijok, W.J.; Guimarães, M.C.C.; Cassini, S.T.A.; de Oliveira, J.P. Impact of Immobilization Strategies on the Activity and Recyclability of Lipases in Nanomagnetic Supports. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtar, N.F.; Rahman, R.N.Z.; Sani, F.; Ali, M.S. Extraction and Reimmobilization of Used Commercial Lipase from Industrial Waste. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 176, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charfi, A.; Aslam, M.; Kim, J. Modelling Approach to Better Control Biofouling in Fluidized Bed Membrane Bioreactor for Wastewater Treatment. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SenSharma, S.; Kumar, G.; Sarkar, A. Chapter 26—Immobilized Enzyme Reactors for Bioremediation. In Metagenomics to Bioremediation; Kumar, V., Bilal, M., Shahi, S.K., Garg, V.K., Eds.; Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 641–657. ISBN 978-0-323-96113-4. [Google Scholar]

- Homaei, A.A.; Sariri, R.; Vianello, F.; Stevanato, R. Enzyme Immobilization: An Update. J. Chem. Biol. 2013, 6, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachosz, K.; Zdarta, J.; Bilal, M.; Meyer, A.S.; Jesionowski, T. Enzymatic Cofactor Regeneration Systems: A New Perspective on Efficiency Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legoy, M.D.; Garde, V.L.; Le Moullec, J.M.; Ergan, F.; Thomas, D. Cofactor Regeneration in Immobilized Enzyme Systems: Chemical Grafting of Functional NAD in the Active Site of Dehydrogenases. Biochimie 1980, 62, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqdi, K.A.; Elmerhi, N.; Athamneh, K.; Bilal, M.; Alzamly, A.; Ashraf, S.S.; Shah, I. Challenges and Recent Advances in Enzyme-Mediated Wastewater Remediation—A Review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojčić, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Bilić Rajs, B.; Strelec, I.; Velić, N.; Brekalo, M.; Hessel, V.; Budžaki, S. Immobilized Pseudomonas Fluorescens Lipase on Eggshell Membranes for Sustainable Lipid Structuring in Cocoa Butter Substitute. Processes 2025, 13, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornla-ied, P.; Podchong, P.; Sonwai, S. Synthesis of Cocoa Butter Alternatives from Palm Kernel Stearin, Coconut Oil and Fully Hydrogenated Palm Stearin Blends by Chemical Interesterification. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme Immobilization Carrier Property | SCG | SCG-Derived Carriers |

|---|---|---|

| Specific surface area [m2/g] | 4.42 | 7.12 |

| Total pore volume [cm3/g] | 4.80 × 10−3 | 7.71 × 10−3 |

| Pore diameter [nm] | 3.40 | 3.80 |

| Immobilization Technique | Adsorption | Direct Covalent | Indirect Covalent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipase Activity | [U/g w.b.] 1 | [U/g l.d.b] 2 | [U/g w.b.] 1 | [U/g l.d.b] 2 | [U/g w.b.] 1 | [U/g l.d.b] 2 |

| BCL | 30.38 ± 0.52 | 233.67 ± 5.51 | 227.75 ± 7.30 | 337.08 ± 4.89 | 40.77 ± 3.51 | 203.31 ± 5.48 |

| PFL | 143.95 ± 2.05 | 441.67 ± 5.51 | 105.55 ± 3.85 | 304.12 ± 8.16 | 44.06 ± 0.69 | 301.73 ± 2.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ostojčić, M.; Brekalo, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Bilić Rajs, B.; Velić, N.; Šarić, S.; Djerdj, I.; Budžaki, S.; Strelec, I. Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9633. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219633

Ostojčić M, Brekalo M, Stjepanović M, Bilić Rajs B, Velić N, Šarić S, Djerdj I, Budžaki S, Strelec I. Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9633. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219633

Chicago/Turabian StyleOstojčić, Marta, Mirna Brekalo, Marija Stjepanović, Blanka Bilić Rajs, Natalija Velić, Stjepan Šarić, Igor Djerdj, Sandra Budžaki, and Ivica Strelec. 2025. "Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9633. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219633

APA StyleOstojčić, M., Brekalo, M., Stjepanović, M., Bilić Rajs, B., Velić, N., Šarić, S., Djerdj, I., Budžaki, S., & Strelec, I. (2025). Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance. Sustainability, 17(21), 9633. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219633