Sustainable Maize Forage Production: Effect of Organic Amendments Combined with Microbial Biofertilizers Across Different Soil Textures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

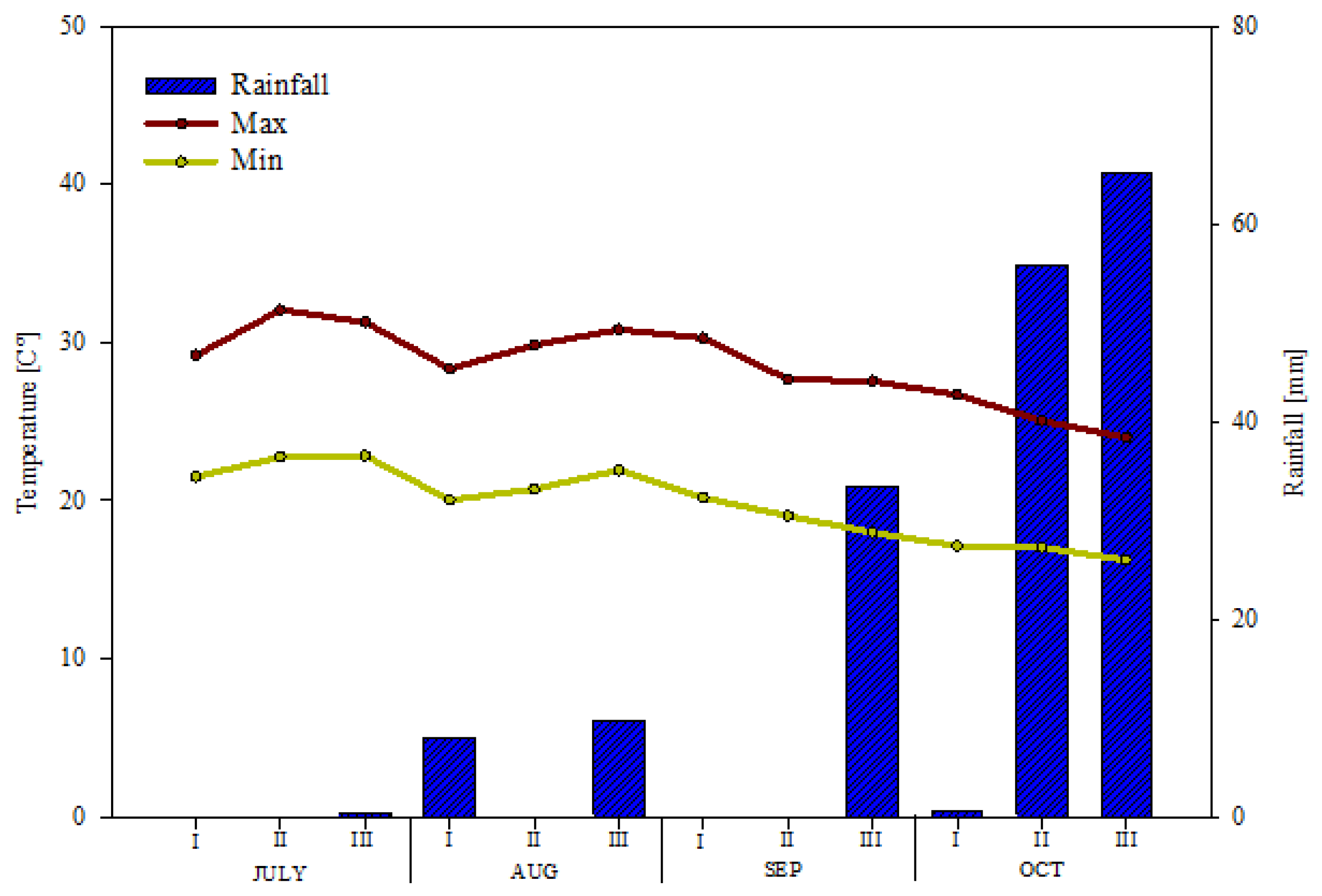

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Setup

2.2. Experimental Measures

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Soil

2.3.2. Maize Biomass

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

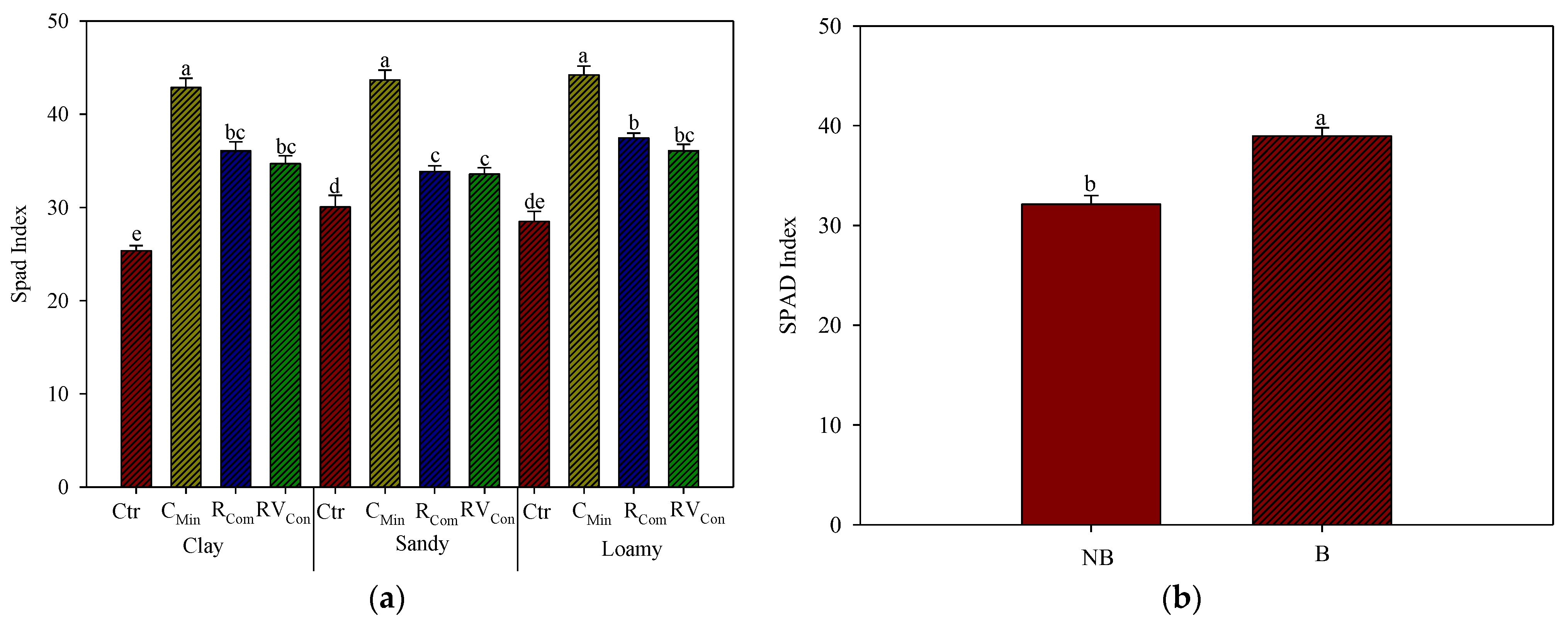

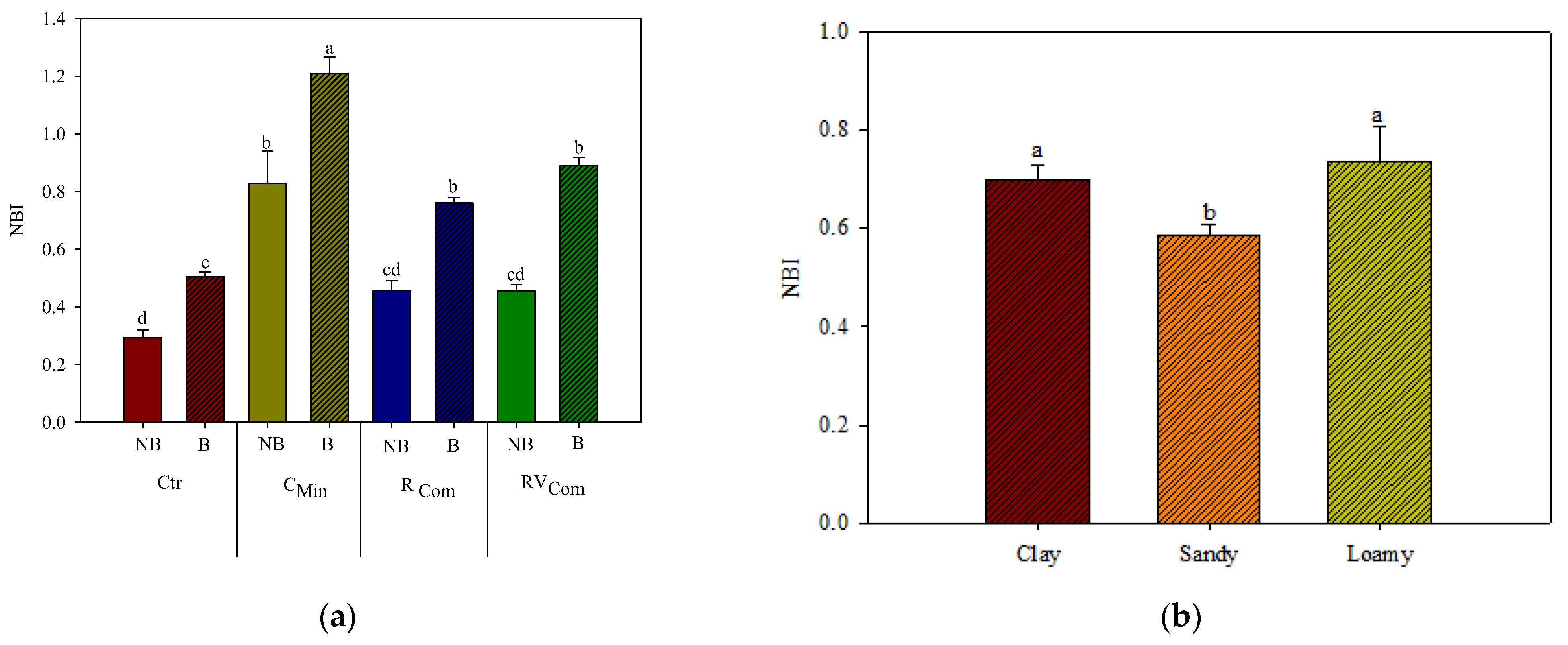

3.1. SPAD and Dualex Measurements

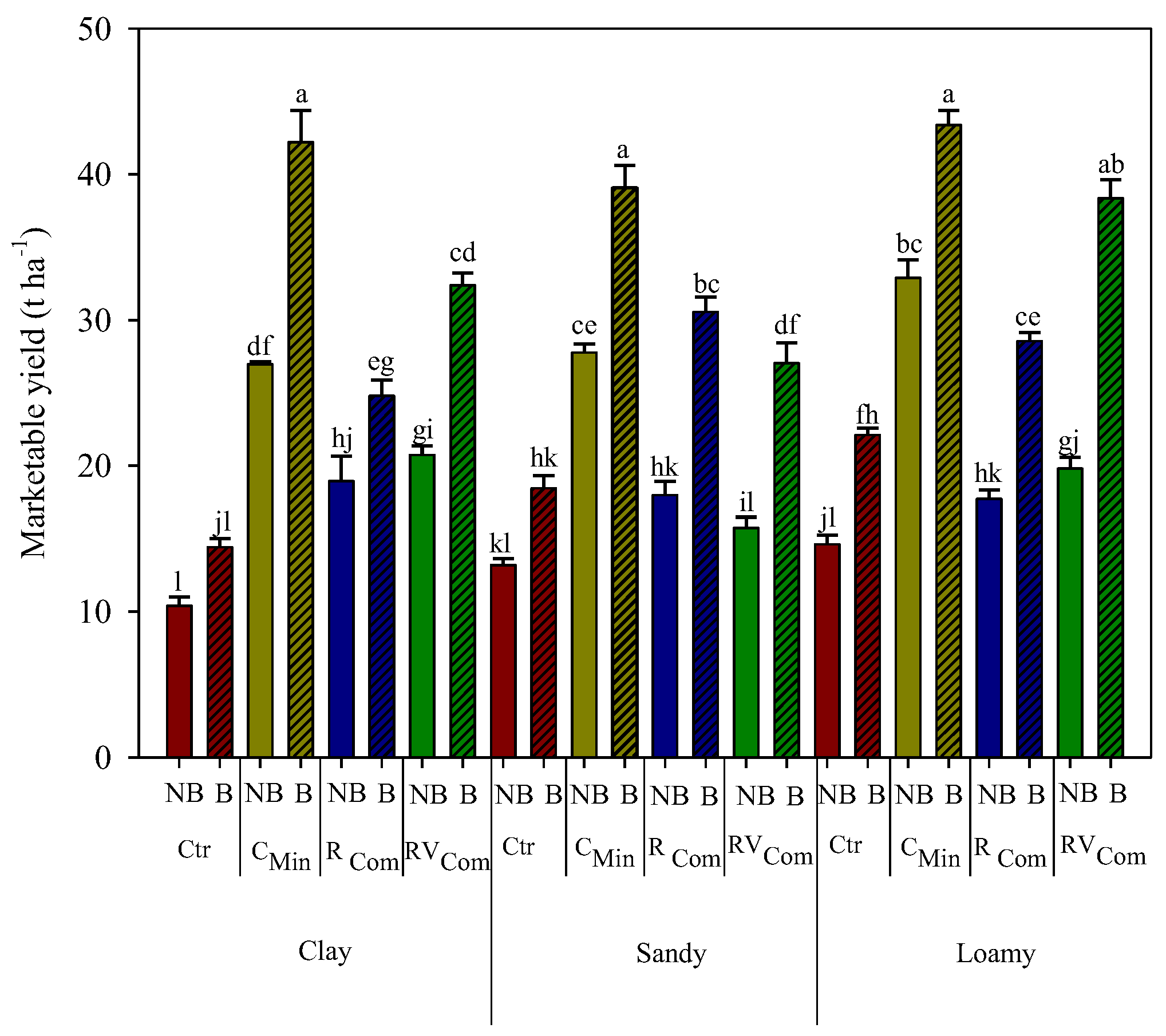

3.2. Maize Yield and Dry Matter Repartition

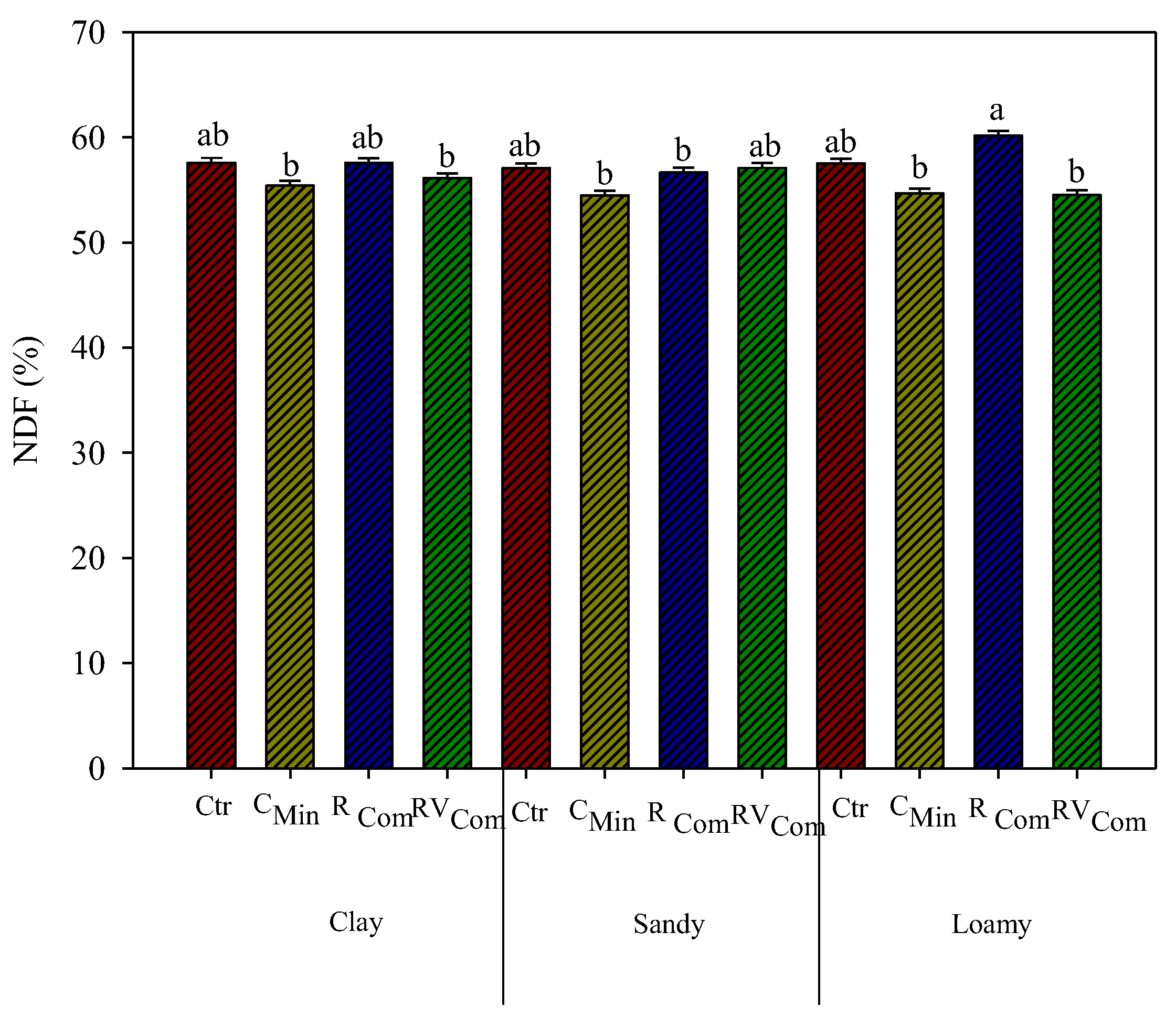

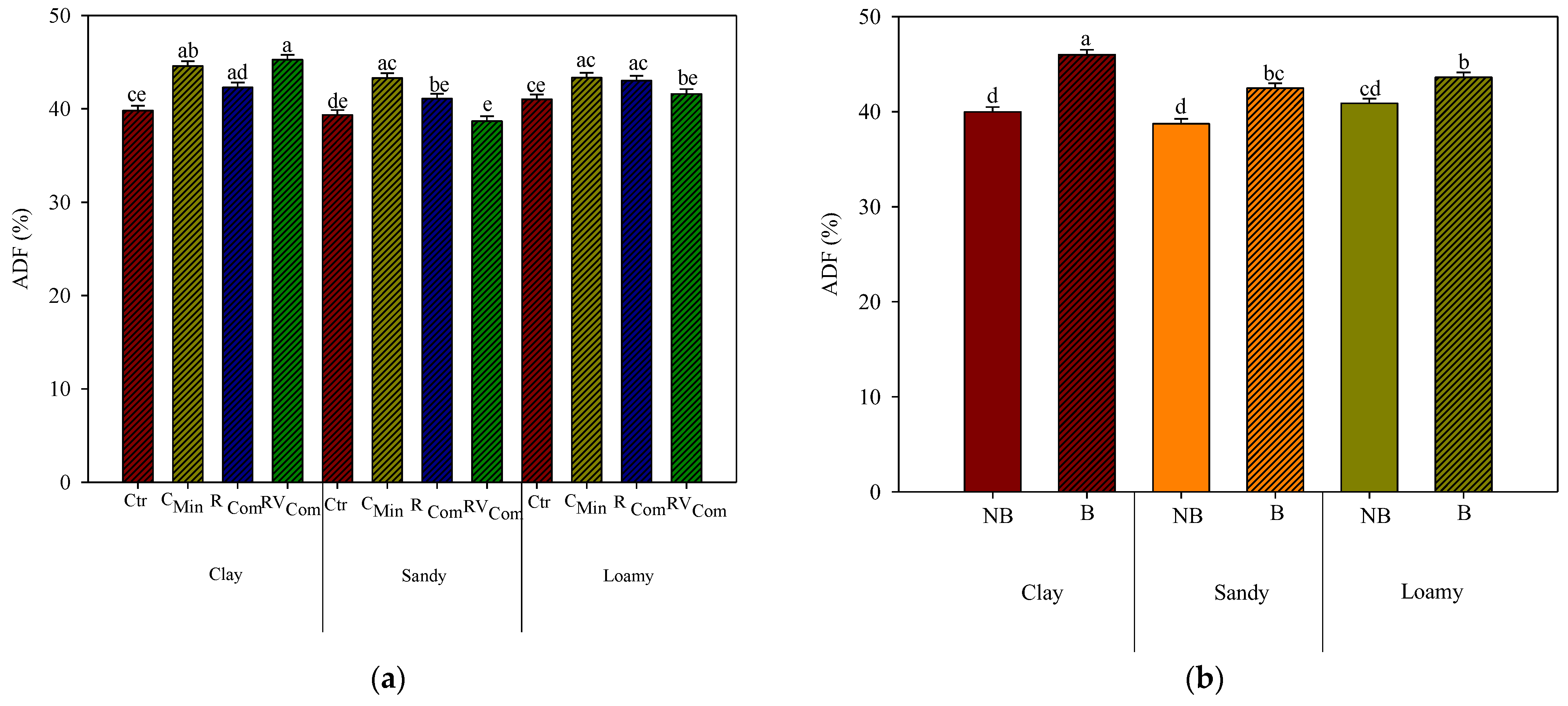

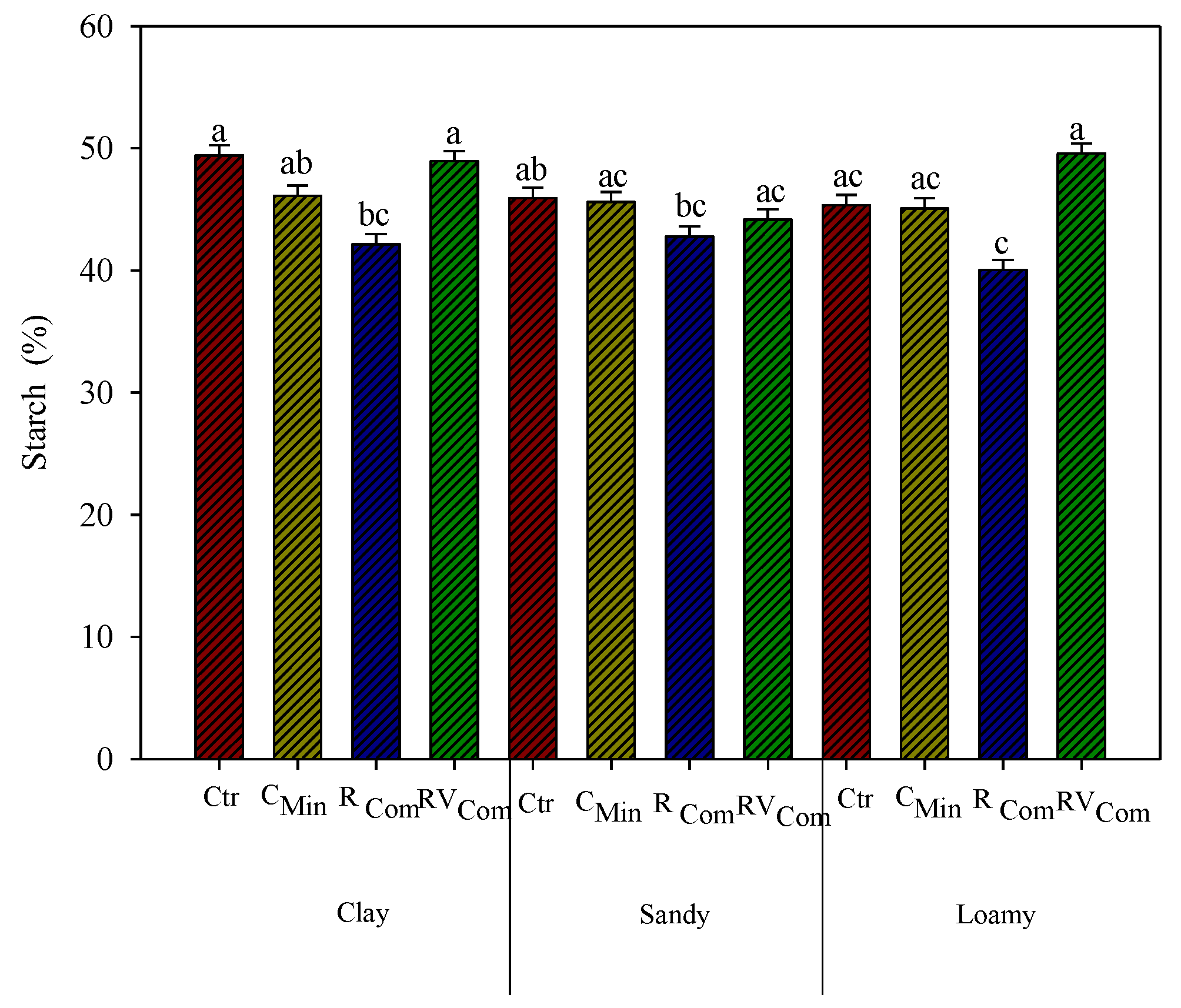

3.3. Maize Chemical Composition and In Vitro Digestibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBF | Bio-based fertilizers |

| Com | Compost |

| VCom | Vermicompost |

| MBF | Microbial biofertilizers |

| B | Treated with MBF |

| NB | Not treated with MBF |

| AMF | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| RCom | Residual fertility from compost |

| RVCom | Residual fertility from vermicompost |

| CMin | Mineral fertilization control |

| Ctr | No-fertilization control |

| DM | Dry matter |

| OM | Organic matter |

| CP | Crude protein |

| EE | Ether extract |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fiber |

| ADF | Acid detergent fiber |

| ADL | Acid detergent lignin |

| IVDMD | In vitro digestibility of dry matter |

| IVNDFD | In vitro digestibility of neutral detergent fiber |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Tyagi, J.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, M. Nitrogenous Fertilizers: Impact on Environment Sustainability, Mitigation Strategies, and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11649–11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuland, G.; Van de Sande, T.; Dekker, H.; Sigurnjak, I.; Meers, E. Digestate in Replacement of Synthetic Fertilisers: A Comparative 3–Year Field Study of the Crop Performance and Soil Residual Nitrates in West-Flanders. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 161, 127380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fertilizer Association (IFA). Top Fertilizer Calls for 2024. CRU Group 2024. Available online: https://www.bcinsight.crugroup.com/2024/01/31/top-ten-fertilizer-calls-for-2024 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural Sustainability and Intensive Production Practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Zhang, X.; Qi, L.; Li, L.; Guo, J.; Zhong, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, J. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer Increases the Uptake of Soil Heavy Metal Pollutants by Plant Community. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 109, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, P.; Arneth, A.; Henry, R.; Maire, J.; Rabin, S.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. High Energy and Fertilizer Prices Are More Damaging than Food Export Curtailment from Ukraine and Russia for Food Prices, Health and the Environment. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, V.; Garagounis, I.; Vourros, A.; Vasileiou, E.; Stoukides, M. An Electrochemical Haber-Bosch Process. Joule 2020, 4, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, I.M.; Lacasa, J.; van Versendaal, E.; Lemaire, G.; Belanger, G.; Jégo, G.; Sandaña, P.G.; Soratto, R.P.; Djalovic, I.; Ata-Ul-Karim, S.T.; et al. Revisiting the Relationship between Nitrogen Nutrition Index and Yield across Major Species. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 154, 127079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goucher, L.; Bruce, R.; Cameron, D.D.; Lenny Koh, S.C.; Horton, P. The Environmental Impact of Fertilizer Embodied in a Wheat-to-Bread Supply Chain. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamini, V.; Singh, K.; Antar, M.; El Sabagh, A. Sustainable Cereal Production through Integrated Crop Management: A Global Review of Current Practices and Future Prospects. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1428687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester-Larsen, L.; Müller-Stöver, D.S.; Salo, T.; Jensen, L.S. Potential Ammonia Volatilization from 39 Different Novel Biobased Fertilizers on the European Market—A Laboratory Study Using 5 European Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröster, M.F. Assessing the Value of Organic Fertilizers from the Perspective of EU Farmers. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarifinnur, S.; Nuraini, Y.; Prasetya, B.; Handayanto, E. Comparing Compost and Vermicompost Produced from Market Organic Waste. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldan, E.; Nedeff, V.; Barsan, N.; Culea, M.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Mosnegutu, E.; Tomozei, C.; Chitimus, D.; Irimia, O. Assessment of Manure Compost Used as Soil Amendment—A Review. Processes 2023, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebe, M.C.; Erasmus, M. Vermicomposting Technology—A Perspective on Vermicompost Production Technologies, Limitations and Prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.S.J.; Hermes, P.H.; Miriam, S.V.; López, A.M. Benefits of Vermicompost in Agriculture and Factors Affecting Its Nutrient Content. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 4898–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Gómez, C.V.; Flórez-Martínez, D.H.; Cayuela, M.L.; Tortosa, G. Compost and Vermicompost Improve Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation, Physiology and Yield of the Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis: A Systematic Review. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2025, 210, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Wester-Larsen, L.; Jensen, L.S.; Salo, T.; Garrido, R.R.; Arkoun, M.; D’Oria, A.; Lewandowski, I.; Müller, T.; Bauerle, A. Agronomic Performance of Novel, Nitrogen-Rich Biobased Fertilizers across European Field Trial Sites. Field Crops Res. 2024, 316, 109486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Xiong, C.; Egidi, E.; Singh, B.K. Formulation Challenges Associated with Microbial Biofertilizers in Sustainable Agriculture and Paths Forward. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Cope, K.R.; Raths, R.; Krishna Yakha, J.; Subramanian, S.; Bücking, H.; Garcia, K. Harnessing Soil Microbes to Improve Plant Phosphate Efficiency in Cropping Systems. Agronomy 2019, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, A.; Toth, G.; Ylivainio, K.; Toth, Z. Opportunities and Challenges of Bio-Based Fertilizers Utilization for Improving Soil Health. Org. Agric. 2023, 13, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscardi, S.; Ventorino, V.; Duran, P.; Maggio, A.; De Pascale, S.; Mora, M.L.; Pepe, O. Assessment of Plant Growth Promoting Activities and Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Azotobacter chroococcum Strains for a Potential Use in Sustainable Agriculture. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 16, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Reheul, D. The Application of Vegetable, Fruit and Garden Waste (VFG) Compost in Addition to Cattle Slurry in a Silage Maize Monoculture: Nitrogen Availability and Use. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 19, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.J.; Han, K.J.; Muir, J.P.; Weindorf, D.C.; Lastly, L. Dairy Manure Compost Effects on Corn Silage Production and Soil Properties. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrouzi, D.; Diyanat, M.; Majidi, E.; Mirhadi, M.J.; Shirkhani, A. Yield and Quality of Forage Maize as a Function of Diverse Irrigation Regimes and Biofertilizer in the West of Iran. J. Plant Nutr. 2023, 46, 2246–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazbawi, I.; Jahanbakhshi, A.; Sepehr, B. Modeling and Optimization of Yield and Physiological Indices of Fodder Maize (Zea mays L.) under the Influence of Vermicompost and Irrigation Percentage Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, L.; Pecetti, L. Wheat yield as a measure of the residual fertility after 20 years of forage cropping systems with different manure management in Northern Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2019, 14, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noceto, P.-A.; Bettenfeld, P.; Boussageon, R.; Hériché, M.; Sportes, A.; van Tuinen, D.; Courty, P.-E.; Wipf, D. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, a Key Symbiosis in the Development of Quality Traits in Crop Production, Alone or Combined with Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, G.M.; Di Mola, I.; Mori, M.; Cozzolino, E.; Morrone, B.; Trasacco, F.; Carillo, P. From Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) Manure to Vermicompost: Testing a Sustainable Approach for Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Di Mola, I. Guida Alla Concimazione: Metodi, Procedure e Strumenti per un Servizio di Consulenza, 1st ed.; Imago Editrice s.r.l.: Dragoni, Italy, 2012; pp. 196–197. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, S.W.; Hanway, J.J.; Benson, G.O. How a Corn Plant Develops; Special Report No. 48; Iowa State University of Science and Technology, Cooperative Extension Service: Ames, IA, USA, 1993; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 18400-102; Soil Quality—Sampling—Part 102: Selection and Application of Sampling Techniques. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 11464; Soil Quality—Pretreatment of Samples for Physico-Chemical Analysis. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Duri, L.G.; Paradiso, R.; Di Mola, I.; Cozzolino, E.; Ottaiano, L.; Marra, R.; Mori, M. Organic Fertilization and Biostimulant Application to Improve Yield and Quality of Eggplant While Reducing the Environmental Impact. Plants 2025, 14, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11277; Soil Quality—Determination of Particle Size Distribution in Mineral Soil Material—Method by Sieving and Sedimentation. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Visconti, D.; Carrino, L.; Fiorentino, N.; El-Nakhel, C.; Todisco, D.; Fagnano, M. Phytomanagement of Shooting Range Soils Contaminated by Pb, Sb, and as Using Ricinus communis L.: Effects of Compost and AMF on PTE Stabilization, Growth, and Physiological Responses. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.N. Nitrate-nitrogen Determination—A Critical Review. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 1994, 25, 2841–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Total Nitrogen. In Methods of Soil Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 1149–1178. ISBN 978-0-89118-204-7. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morari, F.; Lugato, E.; Giardini, L. Olsen Phosphorus, Exchangeable Cations and Salinity in Two Long-Term Experiments of North-Eastern Italy and Assessment of Soil Quality Evolution. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 124, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderman, F.W., Jr.; Sunderman, F.W. Studies in Serum Electrolytes XXII. A Rapid, Reliable Method for Serum Potassium Using Tetraphenylboron. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1958, 29, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicarelli, F.; Sarubbi, F.; Iommelli, P.; Grossi, M.; Lotito, D.; Tudisco, R.; Infascelli, F.; Musco, N.; Lombardi, P. Nutritional Characteristics of Corn Silage Produced in Campania Region Estimated by Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS). Agronomy 2023, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.H.; Mathews, M.C.; Fadel, J.G. Influence of Storage Time and Temperature on in Vitro Digestion of Neutral Detergent Fibre at 48h, and Comparison to 48h in Sacco Neutral Detergent Fibre Digestion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1999, 80, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrapica, F.; Masucci, F.; Raffrenato, E.; Sannino, M.; Vastolo, A.; Barone, C.M.A.; Di Francia, A. High Fiber Cakes from Mediterranean Multipurpose Oilseeds as Protein Sources for Ruminants. Animals 2019, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masucci, F.; Serrapica, F.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Sabia, E.; Balivo, A.; Di Francia, A. Replacing Maize Silage with Hydroponic Barley Forage in Lactating Water Buffalo Diet: Impact on Milk Yield and Composition, Water and Energy Footprint, and Economics. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 9426–9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoero, F.; Gallo, A.; Zanfi, C.; Giuberti, G.; Spanghero, M. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilization on Chemical Composition and Rumen Fermentation of Different Parts of Plants of Three Corn Hybrids. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 164, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, L.; Van linden, V.; De Meester, S.; Vandecasteele, B.; Muylle, H.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Nemecek, T.; Dewulf, J. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Grain Maize Production: An Analysis of Factors Causing Variability. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 553, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingeri, A.; Cabrera, V.; Gallo, A.; Liang, D.; Masoero, F. A Survey of Dairy Cattle Management, Crop Planning, and Forages Cost of Production in Northern Italy. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 18, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrapica, F.; Masucci, F.; De Rosa, G.; Braghieri, A.; Sarubbi, F.; Garofalo, F.; Grasso, F.; Di Francia, A. Moving Buffalo Farming beyond Traditional Areas: Performances of Animals, and Quality of Mozzarella and Forages. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, P.; Masucci, F.; Serrapica, F.; Varricchio, M.L.; Pacelli, C.; Claps, S.; Francia, A.D. Use of Mycorrhizal Inoculum under Low Fertilizer Application: Effects on Forage Yield, Milk Production, and Energetic and Economic Efficiency. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ashraf, M.N.; Sanaullah, M.; Maqsood, M.A.; Waqas, M.A.; Rahman, S.U.; Hussain, S.; Ahmad, H.R.; Mustafa, A.; Minggang, X. Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization Potential of Manures Regulated by Soil Microbial Activities in Contrasting Soil Textures. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 3056–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.u; De Castro, F.; Aprile, A.; Benedetti, M.; Fanizzi, F.P. Vermicompost: Enhancing Plant Growth and Combating Abiotic and Biotic Stress. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Rengel, Z.; George, T.S.; Feng, G. Exploring the Secrets of Hyphosphere of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Processes and Ecological Functions. Plant Soil 2022, 481, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Holanda, S.F.; Vargas, L.K.; Granada, C.E. Challenges for Sustainable Production in Sandy Soils: A Review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.T.T.; Verma, S.L.; Penfold, C.; Marschner, P. Nutrient Release from Composts into the Surrounding Soil. Geoderma 2013, 195–196, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, A.P.; Verma, P.O.; Appel, C. Nitrogen Dynamics of Vermicompost Use in Sustainable Agriculture. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 2016, 7, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Z. Effects of Vermicompost on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. Crispa) Yield in Greenhouse under Different Soil Water Regimes. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 2151–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Romero, D.; Juárez-Sánchez, S.; Venegas, B.; Ortíz-González, C.S.; Baez, A.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. A Bacterial Consortium Interacts with Different Varieties of Maize, Promotes the Plant Growth, and Reduces the Application of Chemical Fertilizer Under Field Conditions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 616757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cano, C.; Ferrández-Gómez, B.; Jordá, J.D.; Cerdán, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, A. Comparative Evaluation of Organic and Conventional Biostimulant Application in Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Plants: Effects on Flowering, Ripening, and Fruit Quality. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Miao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, F. Improving Maize Nitrogen Nutrition Index Prediction Using Leaf Fluorescence Sensor Combined with Environmental and Management Variables. Field Crops Res. 2021, 269, 108180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhezali, A.; Aissaoui, A.E. Feasibility Study of Using Absolute SPAD Values for Standardized Evaluation of Corn Nitrogen Status. Nitrogen. 2021, 2, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Bocianowski, J.; Nowosad, K.; Zielewicz, W.; Kobus-Cisowska, J. SPAD Leaf Greenness Index: Green Mass Yield Indicator of Maize (Zea mays L.), Genetic and Agriculture Practice Relationship. Plants 2021, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.E.; Fraterrigo, J.M. Plant–Microbial Competition for Nitrogen Increases Microbial Activities and Carbon Loss in Invaded Soils. Oecologia 2017, 184, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Roiloa, S.; Yu, F.-H. Potential Roles of Soil Microorganisms in Regulating the Effect of Soil Nutrient Heterogeneity on Plant Performance. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola-Vargas, V.M.; Sánchez de Jiménez, E. Regulation of Glutamine Synthetase/Glutamate Synthase Cycle in Maize Tissues, Effect of the Nitrogen Source. J. Plant Physiol. 1986, 124, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Conn, V.; Plett, D.; Conn, S.; Zanghellini, J.; Mackenzie, N.; Enju, A.; Francis, K.; Holtham, L.; Roessner, U.; et al. The Response of the Maize Nitrate Transport System to Nitrogen Demand and Supply across the Lifecycle. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S.; Nigro, D.; Lasorella, C.; Marcotuli, I.; Gadaleta, A.; de Pinto, M.C. The Role of Glutamine Synthetase (GS) and Glutamate Synthase (GOGAT) in the Improvement of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Cereals. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.-Q.; Lin, H.-X. Contribution of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism to Plant Development and Plant–Environment Interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Feng, K.; Xie, M.; Barros, J.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Muchero, W.; Chen, J.-G. Phylogenetic Occurrence of the Phenylpropanoid Pathway and Lignin Biosynthesis in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 704697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, C.; Cozzolino, V.; Verrillo, M.; Vinci, G.; De Martino, A.; Scopa, A.; Piccolo, A. Combination of Humic Biostimulants with a Microbial Inoculum Improves Lettuce Productivity, Nutrient Uptake, and Primary and Secondary Metabolism. Plant Soil 2022, 481, 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Fang, Y.; Hou, H.; Lei, K.; Ma, Y. Regulation of Density and Fertilization on Crude Protein Synthesis in Forage Maize in a Semiarid Rain-Fed Area. Agriculture 2023, 13, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, E.G.; Silva, C.A.; Maluf, H.J.G.M.; Paiva, I.d.O.; de Paula, L.H.D. Effects of Compost-Based Organomineral Fertilizers on the Kinetics of NPK Release and Maize Growth in Contrasting Oxisols. Waste Biomass Valor. 2023, 14, 2299–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Li, G.; Dong, S. The Role of Nitrogen in Leaf Senescence of Summer Maize and Analysis of Underlying Mechanisms Using Comparative Proteomics. Plant Sci. 2015, 233, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Shi, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Dong, S. The Mechanisms of Low Nitrogen Induced Weakened Photosynthesis in Summer Maize (Zea mays L.) under Field Conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 105, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejbaruah, R.; Sharma, R.C.; Banik, P. Split Application of Vermicompost to Rice (Oryza sativa L.): Its Effect on Productivity, Yield Components, and N Dynamics. Org. Agric. 2013, 3, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, V.; Romano, I.; Woo, S.L.; Di Stasio, E.; Lombardi, N.; Comite, E.; Pepe, O.; Ventorino, V.; Maggio, A. Inoculation with a Microbial Consortium Increases Soil Microbial Diversity and Improves Agronomic Traits of Tomato under Water and Nitrogen Deficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1304627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figiel, S.; Rusek, P.; Ryszko, U.; Brodowska, M.S. Microbially Enhanced Biofertilizers: Technologies, Mechanisms of Action, and Agricultural Applications. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Giuberti, G.; Masoero, F.; Palmonari, A.; Fiorentini, L.; Moschini, M. Response on Yield and Nutritive Value of Two Commercial Maize Hybrids as a Consequence of a Water Irrigation Reduction. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 13, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameldin, H.; Izadi-Darbandi, A.; Smith, S.A.; Balan, V.; Jones, A.D.; Sticklen, M. Production of Seed-like Storage Lipids and Increase in Oil Bodies in Corn (Maize; Zea mays L.) Vegetative Biomass. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Ren, B.; Zhao, B.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J. Nitrogen Rate Effects Reproductive Development and Grain Set of Summer Maize by Influencing Fatty Acid Metabolism. Plant Soil 2023, 487, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawke, J.C.; Rumsby, M.G.; Leech, R.M. Lipid Biosynthesis in Green Leaves of Developing Maize 1. Plant Physiol. 1974, 53, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolera, A.; Sundstøl, F. Morphological Fractions of Maize Stover Harvested at Different Stages of Grain Maturity and Nutritive Value of Different Fractions of the Stover. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1999, 81, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Malvar, A.; Malvar, R.A.; Souto, X.C.; Gomez, L.D.; Simister, R.; Encina, A.; Barros-Rios, J.; Pereira-Crespo, S.; Santiago, R. Elucidating the Multifunctional Role of the Cell Wall Components in the Maize Exploitation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, F.; Alborino, V.; Dini, I.; Balestrieri, A.; Marra, R.; Davino, R.; Di Francia, A.; Masucci, F.; Serrapica, F.; Vinale, F. In Vitro Application of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes from Trichoderma Spp. to Improve Feed Utilization by Ruminants. Agriculture 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastolo, A.; Matera, R.; Serrapica, F.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Neglia, G.; Kiatti, D.d.; Calabrò, S. Improvement of Rumen Fermentation Efficiency Using Different Energy Sources: In Vitro Comparison between Buffalo and Cow. Fermentation 2022, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Texture | Fertilization | OM, % | Total N, % | pH | NO3-N, ppm | NH4-N, ppm | P2O5, ppm | K2O, ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay 1 | Ctr | 1.66 | 0.09 | 7.72 | 59.11 | 13.40 | 48.11 | 1592 |

| RVCom | 1.79 | 0.10 | 7.65 | 61.89 | 15.40 | 92.21 | 1633 | |

| RCom | 2.25 | 0.11 | 7.53 | 60.23 | 16.22 | 55.23 | 1665 | |

| Min | 1.79 | 0.09 | 7.82 | 62.35 | 13.77 | 50.81 | 1601 | |

| Loamy 2 | Ctr | 1.96 | 0.10 | 7.61 | 14.33 | 11.50 | 74.32 | 1161 |

| RVCom | 2.48 | 0.14 | 7.59 | 15.45 | 12.2 | 87.65 | 1199 | |

| RCom | 1.95 | 0.12 | 7.56 | 15.21 | 13.18 | 82.32 | 1208 | |

| Min | 1.98 | 0.12 | 7.73 | 15.89 | 11.80 | 82.63 | 1161 | |

| Sandy 3 | Ctr | 1.63 | 0.11 | 7.74 | 17.41 | 8.27 | 43.71 | 723 |

| RVCom | 2.19 | 0.13 | 7.56 | 18.25 | 8.72 | 82.79 | 748 | |

| RCom | 1.72 | 0.11 | 7.62 | 18.18 | 9.17 | 55.94 | 755 | |

| Min | 1.58 | 0.11 | 7.82 | 19.12 | 8.25 | 56.62 | 729 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrapica, F.; Di Mola, I.; Cozzolino, E.; Ottaiano, L.; Sarubbi, F.; Pezzullo, G.; Di Francia, A.; Mori, M.; Masucci, F. Sustainable Maize Forage Production: Effect of Organic Amendments Combined with Microbial Biofertilizers Across Different Soil Textures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219617

Serrapica F, Di Mola I, Cozzolino E, Ottaiano L, Sarubbi F, Pezzullo G, Di Francia A, Mori M, Masucci F. Sustainable Maize Forage Production: Effect of Organic Amendments Combined with Microbial Biofertilizers Across Different Soil Textures. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219617

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrapica, Francesco, Ida Di Mola, Eugenio Cozzolino, Lucia Ottaiano, Fiorella Sarubbi, Giannicola Pezzullo, Antonio Di Francia, Mauro Mori, and Felicia Masucci. 2025. "Sustainable Maize Forage Production: Effect of Organic Amendments Combined with Microbial Biofertilizers Across Different Soil Textures" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219617

APA StyleSerrapica, F., Di Mola, I., Cozzolino, E., Ottaiano, L., Sarubbi, F., Pezzullo, G., Di Francia, A., Mori, M., & Masucci, F. (2025). Sustainable Maize Forage Production: Effect of Organic Amendments Combined with Microbial Biofertilizers Across Different Soil Textures. Sustainability, 17(21), 9617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219617