1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has long been viewed as a pathway to economic mobility and social empowerment, serving as a catalyst for innovation, job creation, and economic growth. However, persistent inequities continue to disadvantage women and minority entrepreneurs, limiting their access to critical resources necessary for venture success. Despite evidence that diverse founding teams, such as women and minority entrepreneurs, produce better financial outcomes, more innovative solutions [

1], bring unique perspectives, address underserved markets, and create businesses that contribute to community development and social welfare [

2], structural barriers reify disparities that prevent women and minority entrepreneurs from fully realizing their potential. Recent studies illustrate this stark imbalance. Women entrepreneurs receive less than 2% of all venture capital in the United States while Black and Latinx founders receive less than 3% combined [

3,

4]. These disparities persist even when controlling for education, experience, and industry, suggesting deep seated systemic barriers.

Such inequities are not merely economic inefficiencies but present deep concerns for social sustainability. Inclusive entrepreneurship is linked to resilient economies, job creation in underserved communities, and pathways for intergenerational wealth-building [

5,

6]. On the other hand, exclusion from these opportunity and resource structures reinforce cycles of inequality and undermines progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 5 (gender equality), Goal 8 (decent work and economic growth), and Goal 10 (reduced inequalities). Addressing entrepreneurial inequities is therefore critical to advance both economic and social sustainability.

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) presents an unprecedented opportunity for technology to address these inequities. AI has evolved from a passive analytical tool to an active co-creation partner capable of generating ideas, providing mentorship, facilitating connections, and supporting dynamic human-technology collaboration [

7,

8,

9]. Conceptualizing AI as a co-creation partner rather than a passive analytical tool opens new possibilities for expanding entrepreneurial capacity and democratizing access to critical resources [

10,

11]. Unlike traditional interventions that often require significant human and financial resources, AI-based solutions can provide personalized, on-demand support at scale, potentially democratizing access to entrepreneurial resources [

12]. For women and minority entrepreneurs, AI can operate as a multiplier of social capital across structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions [

13].

To clarify how AI actually functions for entrepreneurs, modern systems such as ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA USA), Claude Sonnet 4.5 and Haiku 4.5 (Anthropic, San Francisco, CA USA), Gemini-2.5-flash (Google, Mountain View, CA USA), and Perplexity AI (San Francisco, CA USA) are large-scale language models trained on diverse corpora of text, code, and other modalities. Increasingly, they use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which lets founders ground responses in up-to-date, user-provided materials (docs, sites, databases). Access models are practical today—free web portals, low-cost subscriptions (≈USD 20/month professional tiers), enterprise integrations (Microsoft 365 Copilot; Google Workspace), and APIs for embedding AI into custom workflows. No-code tools (e.g., Zapier AI (Zapier Inc., San Francisco, CA USA), ManyChat (ManyChat, Inc., San Francisco, CA USA)) allow deployment of chatbots, workflow automation, and customer service with minimal technical skill. In short, AI is already operational for everyday entrepreneurs, not merely experimental.

However, the integration of AI into entrepreneurial development is not without risks. AI systems trained on historical data can perpetuate and even amplify existing biases, potentially exacerbating rather than alleviating inequities [

14,

15]. Thus, safeguards against algorithmic discrimination and ensuring equitable access to these technologies are needed and AI’s role in entrepreneurship is best understood as a site of contestation. It may either entrench and reify existing inequalities or provide tools to overcome them depending upon how it is designed, deployed, and governed. This paper addresses the following research question; How can AI be leveraged as a co-creation tool to enhance beneficial social capital for women and minority entrepreneurs, thereby addressing critical resource gaps and overcoming social inequities in entrepreneurship? To answer this, we conceptualize AI as both a relational resource and a strategic capability [

16]. Through social capital theory and resource-based view (RBV) lenses, we argue that AI, when designed and implemented with intentionality, can serve as a powerful co-creation tool and partner that can democratize access to entrepreneurial resources. Specifically, by enhancing social capital across its structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, AI can co-create with women and minority entrepreneurs to overcome barriers to funding, mentorship, and knowledge acquisition and, when used strategically, can help achieve a competitive advantage. Thus, the research gap suggests that while prior work examines social capital and competitive advantage through a resource-based view lens, little explains how AI simultaneously acts as a relational resource, a knowledge partner, and a strategic capability that can democratize access for underrepresented founders. This paper presents theories that link explicitly to these gaps alongside testable propositions.

Our analysis reveals that AI’s potential impact operates through multiple mechanisms. Firstly, AI can enhance structural social capital by identifying valuable connections, optimizing weak tie formation, and bridging structural holes in networks. Secondly, AI strengthens relational social capital through trust-building mechanisms, enhanced communication across cultural boundaries, and relationship maintenance at scale. Thirdly, AI facilitates cognitive social capital by enabling knowledge translation, narrative alignment, and the development of shared mental models across diverse stakeholder groups.

This paper makes several key contributions. Firstly, we develop a theoretical framework that integrates social capital theory and resource-based view perspectives to understand AI’s role in fostering entrepreneurial equity. Secondly, we identify specific mechanisms through which AI can address resource gaps for underrepresented entrepreneurs. Thirdly, we analyze the risks and barriers to equitable AI implementation, including algorithmic bias, digital divides, and societal resistance. Fourthly, we propose governance strategies to ensure AI’s equitable deployment in entrepreneurial contexts. Finally, we provide AI-generated hypotheticals, grounded in the Los Angeles entrepreneurial ecosystem, to illustrate practical applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We begin with a review of the theoretical foundations of social capital and RBV, highlighting their relevance to entrepreneurial resource gaps experienced by women and minority entrepreneurs, and AI’s evolution as a co-creation tool. We then present our conceptual framework and develop five testable propositions regarding AI’s impact on structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital. Next, we illustrate the framework through AI-generated, Los Angeles-based hypothetical cases demonstrating practical applications in diverse contexts. Finally, we discuss implications for research, practice, and policy, highlight limitations, and outline pathways for future research on AI, entrepreneurship, and sustainability.

3. Conceptual Framework Development

3.1. AI and the Democratization of Social Capital in Entrepreneurship

The integration of AI into entrepreneurial practice represents a structural inflection point in how social capital is developed, accessed, and leveraged. Entrepreneurship research has long demonstrated that access to networks, relationships, and shared knowledge is central to resource mobilization, opportunity recognition, and venture success [

13]. Yet, women and minority entrepreneurs often remain excluded from elite networks, high-value mentorship, and knowledge flows due to systemic inequities in access, recognition, and representation [

44]. This exclusion translates into tangible disadvantages in raising capital, building partnerships, and scaling ventures.

AI, when conceptualized as a socio-technical augmenting force rather than a substitute for human interaction, has the potential to democratize access to the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital. Unlike traditional pathways of network development that rely heavily on geography, cultural fit, or inherited privilege, AI offers systematic and scalable mechanisms that can mitigate structural inequities while creating new pathways to entrepreneurial equity. For example, AI-driven platforms can identify compatible investors, mentors, or collaborators based on objective criteria, thereby reducing reliance on existing social hierarchies and subjective gatekeeping.

By embedding AI into the architecture of entrepreneurial ecosystems, underrepresented founders can potentially overcome entrenched barriers in resource access, mentorship availability, and cultural legitimacy. By enhancing discoverability, facilitating knowledge sharing, and enabling data-driven decision-making, AI can amplify the reach and efficacy of social networks that were previously inaccessible. In this context, AI functions not merely as a technological tool but as a catalyst for more inclusive entrepreneurial practices.

In the following sections, we present a theoretical model that delineates the mechanisms through which AI can enhance social capital for underrepresented entrepreneurs and offer five propositions regarding its potential to foster social equity and competitive advantage.

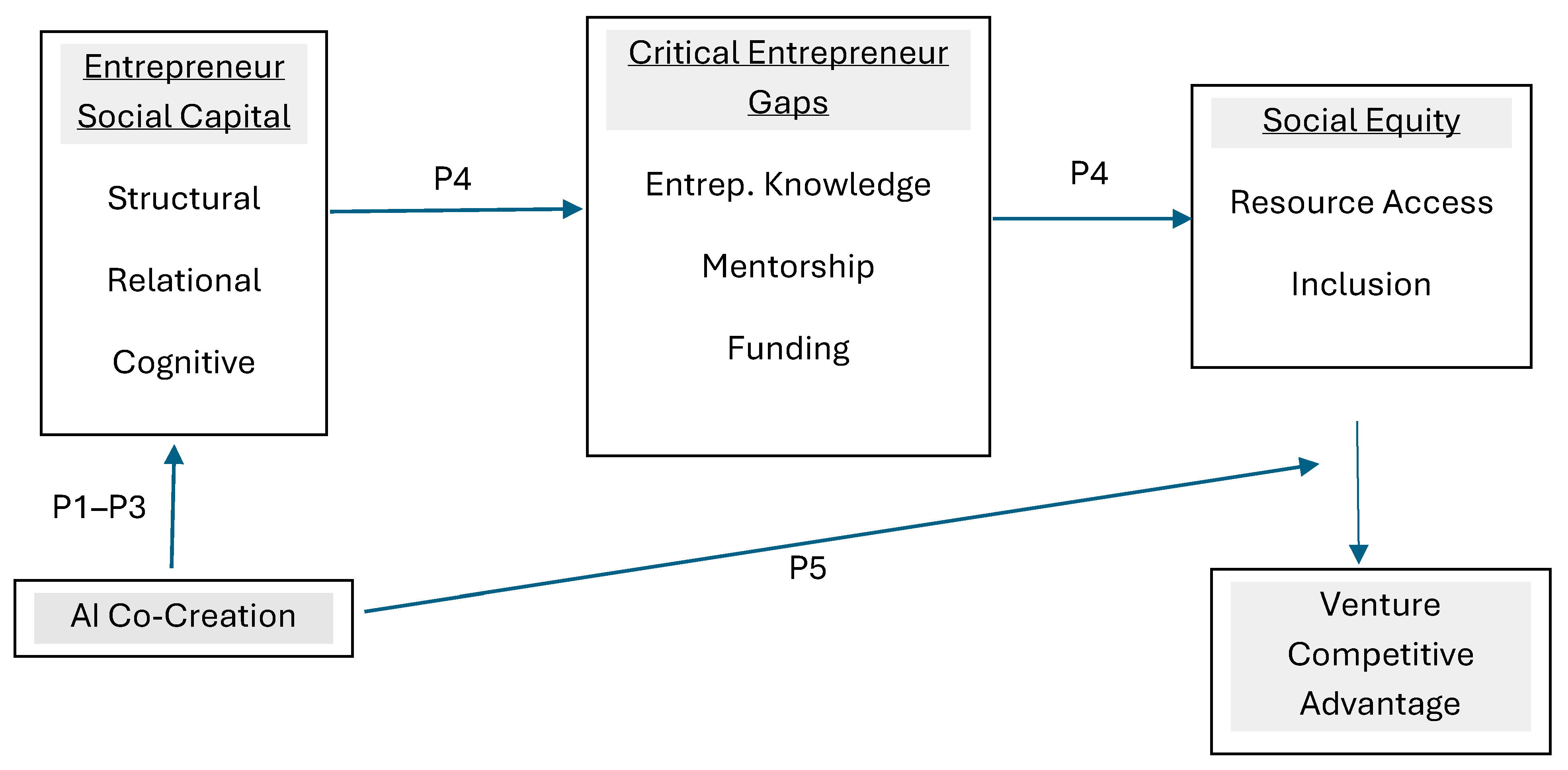

Figure 1 provides an overview of the conceptual framework guiding these propositions. Propositions are supported by AI-generated illustrative hypotheticals from Los Angeles.

Methodological note and testability: We organize the framework as five explicit propositions spanning structural, relational, and cognitive social capital. These propositions are testable via (a) surveys that measure network breadth, trust, and shared cognition pre-/post-AI adoption; and (b) longitudinal case studies tracking venture outcomes. Replication: The hypotheticals were developed with publicly available LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT-4o, Claude 3, Gemini 1.5) using RAG to combine general corpora with user-provided context. In this paper, AI outputs serve as structured thought experiments—boundary objects to animate mechanisms—not as empirical evidence.

3.2. Enhancing Structural Social Capital Through AI

Structural social capital refers to the configuration and breadth of connections across a network [

13]. Historically, proximity, institutional affiliation, and insider access constrained structural social capital, particularly for women and minority entrepreneurs excluded from elite “old boys’ networks” or prestigious institutions [

30]. AI-enabled tools reconfigure these constraints by systematically expanding network opportunities.

Intelligent recommendation systems, for instance, allow entrepreneurs to identify high-value connections based on complementary skills, trajectories, and market trends rather than serendipity or insider privilege [

66]. In doing so, these systems operationalize Granovetter’s [

21] insight regarding weak ties, highlighting the importance of distant connections likely to yield valuable opportunities while compensating for resource-poor strong-tie networks among marginalized groups [

67]. AI-mediated platforms further lower participation barriers by structuring exchanges around skill-based criteria, creating alternatives to traditional spaces where women and minority entrepreneurs often encounter cultural or gendered exclusion [

68].

Beyond expanding connections, AI can identify structural holes and facilitates bridging across disconnected network clusters [

24]. Minority entrepreneurs who navigate both community networks and mainstream markets can thus be positioned as brokers, generating both social capital and market insight. The scalability of AI also reduces the time-intensive burden of relationship building, an advantage particularly salient for women balancing multiple roles or minority entrepreneurs lacking institutional support. Through these mechanisms, AI transforms structural social capital from an exclusionary privilege into an inclusive enabler of entrepreneurial opportunity.

Hypothetical Case: Maria Rodriguez, East LA Manufacturing

Create a detailed hypothetical case study of a Mexican American woman entrepreneur in East Los Angeles who uses AI to enhance her structural social capital and expand her business networks.

Context:

- -

Focus on how AI helps bridge geographic and social divides

- -

Demonstrate weak tie optimization and structural hole bridging

- -

Show progression from local community networks to mainstream markets—Include specific, realistic AI tools available today (RAG, cloud workspaces, networking apps)

- -

Set measurable outcomes over 18-month period.

Requirements:

- -

Age 35–45, inherits/runs existing manufacturing business

- -

Geographic isolation from mainstream fashion/business networks

- -

Show specific AI implementation steps that are replicable today—Include revenue growth, employment expansion, client diversification

- -

Maintain cultural authenticity while accessing mainstream markets.

Maria Rodriguez, a 42-year-old Mexican American entrepreneur, inherited a textile manufacturing business in East Los Angeles, employing 15 local workers. Despite deep industry knowledge and community ties, Maria faced barriers scaling into West LA’s fashion markets due to geographic isolation and limited access to mainstream networks.

Through participation in a pilot program by the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator, Maria implemented AI-powered market analysis and network recommendation tools. AI identified sustainable fashion brands seeking local manufacturers, optimized pricing strategies, and connected her to minority-focused funding opportunities and peer networks. Within 18 months, Maria’s revenue increased by 145%, employment grew from 15 to 38, and her client base expanded from 8 to 23 brands, including five national labels. AI’s structural social capital enhancement enabled Maria to bridge the gap between East LA manufacturing expertise and mainstream fashion networks without sacrificing authenticity.

Process details (replicable today): Maria uploaded company info and past sales into a cloud AI workspace (e.g., ChatGPT Enterprise or Gemini for Workspace). Using RAG, the system linked internal data with market reports to segment customers and suggest target buyers. A no-code AI networking app then recommended investors and brands based on goals, geography, and production records. Finally, an AI financial planner simulated pricing strategies with side-by-side projections. Comparable tools exist now (ChatGPT, Perplexity Pro, Zapier AI, AI-enabled CRMs like Salesforce/HubSpot); integrated incubator bundles remain experimental.

Proposition 1. AI co-creation through network analysis and recommendation systems will significantly enhance women and minority entrepreneurs’ ability to develop structural social capital, particularly weak ties that provide access to novel resources and opportunities, thereby reducing their disadvantage relative to entrepreneurs with established network access.

This proposition predicts that AI’s impact on structural social capital will manifest through several measurable mechanisms. AI-powered network mapping will increase the total number of professionally relevant connections for women and minority entrepreneurs at rates exceeding that of traditional networking methods. The quality of these connections, measured by their relevance to business needs and access to resources, will surpass those formed through chance encounters or standard introductions.

Weak tie optimization enabled by AI will result in more diverse networks with greater reach into different industries, geographic regions, and resource pools. Entrepreneurs using AI-powered networking tools are anticipated to develop greater bridging capital, facilitating access to non-redundant information, earlier awareness of market opportunities, and increased likelihood of strategic partnerships. Furthermore, AI-facilitated virtual networking particularly benefits entrepreneurs facing barriers to conventional networking venues. Women entrepreneurs with caregiving responsibilities and minority entrepreneurs in geographically isolated areas can establish otherwise inaccessible connections. The asynchronous nature of AI-mediated networking accommodates diverse communication styles and time zones, enabling global network development.

Empirical testing of this proposition could involve comparing network metrics—size, diversity, reach, and resource access—between AI users and control groups relying on traditional methods. Longitudinal studies could track weak tie formation and the evolution of network value over time. The proposition anticipates that the networking gap between women and minority entrepreneurs and their traditionally advantaged counterparts will narrow more rapidly among AI users than non-users. The effectiveness of AI in enhancing structural social capital presupposes access to digital infrastructure and a minimum level of AI literacy. Geographic isolation, traditional relationship-based business cultures, and lack of ecosystem support may constrain outcomes. Thus, AI serves as an enabling tool rather than a universal solution, requiring complementary organizational and infrastructural support to realize its full potential.

3.3. Strengthening Relational Social Capital Through AI

Relational social capital, encompassing trust, reciprocity, and mutual identification, is another domain in which AI offers transformative potential. Traditional trust-building often requires extended interactions, which are both time-intensive and largely inaccessible to those outside established circles of legitimacy. For women and minority entrepreneurs, these constraints are compounded by systemic biases that affect credibility, reputation, and mentorship access [

69]. AI can strengthen relational social capital by increasing transparency, mitigating bias, and enabling relationship maintenance at scale.

Blockchain-integrated ledgers and verification systems, for example, authenticate interactions and reduce trust-building burden that disproportionately affect underrepresented entrepreneurs. Natural language processing (NLP) and sentiment analysis mitigate miscommunication and counteract gendered or cultural biases in interpreting behaviors [

70,

71]. AI-powered customer relationship management systems maintain personalized interactions over time, allowing entrepreneurs to nurture networks despite limited availability or resources [

72].

Mentorship exemplifies AI’s capacity to enhance relational social capital. The scarcity of experienced women and minority mentors limits access to critical tacit knowledge. AI-augmented mentorship systems offer hybrid solutions in which technology addresses routine guidance while human mentors focus on high-value engagement. These systems can analyze thousands of mentorship interactions to extract collective intelligence, effectively democratizing access to experiential knowledge for entrepreneurs without direct mentor connections [

73]. By aligning mentors and mentees based on personality traits, communication styles, and learning preferences rather than solely on demographic similarity, AI enhances the quality, efficacy, and inclusivity of mentoring relationships [

74]. Continuous AI-mediated support ensures guidance is available at critical decision-making moments, extending relational capital even under constraints of time and availability [

75]. In this manner, AI complements rather than replaces human trust and reciprocity, broadening access while reduces scarcity.

Hypothetical Case: Keisha Williams, South LA Wellness Tech

Generate a case study of a Black woman entrepreneur in South LA launching a health tech startup, focusing on how AI strengthens relational social capital and trust-building.

Context:

- -

Intersectional barriers in male-dominated tech ecosystem

- -

AI-enabled investor matching and relationship management

- -

Bridge community health networks with Silicon Beach tech resources

- -

Demonstrate trust-building, communication enhancement, relationship maintenance at scale.

Requirements:

- -

Age 30–40, digital health platform addressing health disparities

- -

Show AI tools for investor filtering, narrative tailoring, relationship management—Include specific funding outcomes, partnership numbers, network expansion

- -

Use current AI tools (ChatGPT/Claude/Gemini, CRM integrations, automation)

- -

Demonstrate both technical and relational capital building.

Keisha Williams, a 35-year-old Black woman entrepreneur, launched a digital health platform addressing maternal health disparities in South Los Angeles. Facing intersectional barriers in the male-dominated tech ecosystem, Keisha leveraged AI for investor matching, narrative tailoring, and hybrid network building. AI identified investors with genuine commitments to diversity, suggested pitch strategies for different audiences, and facilitated connections, bridging South LA health networks with Silicon Beach tech resources. As a result, Keisha raised USD 2.5 million in seed funding, partnered with 12 community health centers, and expanded her network across investors, healthcare executives, and policymakers. AI-supported relational capital enabled trust-building and reciprocity that would have been difficult through traditional networking.

Process details: Keisha used an investor-matching agent to filter funds by thesis, stage, and diversity track record; a narrative-tailoring assistant produced pitch versions for healthcare execs versus seed VCs; and a relationship-management AI scheduled follow-ups and summarized meetings. These workflows can be built today with general models (ChatGPT/Claude/Gemini), calendar-CRM integrations, and lightweight automation (e.g., Zapier AI).

Proposition 2. AI co-creation through communication and relationship management tools will strengthen the relational dimension of social capital for women and minority entrepreneurs by facilitating trust-building, enhancing cross-cultural communication, and enabling relationship maintenance at scale, thereby improving the quality and value of their network relationships.

This proposition emphasizes relationship quality over quantity. AI is expected to accelerate trust-building through transparency mechanisms that allow women and minority entrepreneurs to establish credibility more quickly than through traditional reputation-building processes. Blockchain-integrated AI systems that create verifiable records of business interactions and outcomes will reduce the “trust discount” often applied to entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups, resulting in faster progression from initial contact to substantive business relationships.

AI also enhances communication across cultural and gender boundaries. NLP tools that provide real-time feedback on communication effectiveness can help women entrepreneurs navigate the double bind of appearing both competent and likable while minority entrepreneurs using AI-powered translation and cultural intelligence tools may experience fewer failed partnerships due to cultural misunderstandings and higher satisfaction with cross-cultural interactions.

Relationship maintenance is further enabled by AI, particularly for entrepreneurs managing multiple responsibilities. AI-powered CRM systems allow women and minority entrepreneurs to maintain active engagement with larger networks, achieve higher response rates, and sustain more frequently meaningful interactions. Reciprocity facilitation through AI also allows resource-constrained entrepreneurs to contribute value to their networks via non-monetary exchanges, which strengthens centrality and recognition within the network.

Testing this proposition requires measuring relationship quality through surveys assessing trust, reciprocity, and perceived value of network relationships as well as evaluating communication effectiveness via response rate, collaboration success, and relationship longevity. The prediction is that relational social capital gaps will narrow most dramatically for entrepreneurs facing significant cultural or communication barriers. Boundary conditions include the recognition that AI cannot fully replace human mentorship and the effectiveness of these tools may be constrained by cultural norms, communication styles, or hostile/indifferent entrepreneurial ecosystems. Access to digital infrastructure and basic AI literacy also remain prerequisites for meaningful engagement.

3.4. Facilitating Cognitive Social Capital Through AI

Cognitive social capital refers to shared representations, mental models, and systems of meaning that enable coordinated action and collective understanding [

13]. These shared understandings are often tacitly encoded within dominant business cultures, creating cognitive barriers for underrepresented entrepreneurs who must translate community-centered logics into the frameworks that govern venture capital, market legitimacy, and institutional recognition. AI offers bridging mechanisms that allow entrepreneurs to navigate these cognitive gaps, aligning their narratives and practices with mainstream evaluative criteria without eroding authenticity.

Generative AI, for example, can translate social impact goals into financial performance metrics intelligible to investors [

64,

76]. AI-enabled collaboration platforms make implicit assumptions visible within diverse teams, enabling the negotiation of shared mental models that strengthen cohesion and decision-making [

77]. Cultural intelligence systems further enhance this bridging capacity by providing real-time guidance on context-specific norms and practices across different markets, mitigating the risk of miscommunication or cultural missteps [

78].

AI also addresses knowledge gaps that have historically disadvantaged women and minority founders. Formal business education and informal knowledge transfer are often embedded in elite ecosystems, privileging founders with existing access to networks, mentors, and precedent-setting examples. AI democratizes knowledge by tailoring learning pathways to individual entrepreneurs’ backgrounds, goals, and learning styles [

79]. Contextualized, just-in-time delivery ensures information is available at critical decision points—such as negotiation guidance upon receiving a term sheet—enhancing decision quality and strategic agility [

80]. Unlike traditional curricula that often reflect the experiences of white, male, Western entrepreneurs, AI can curate culturally relevant examples, simulations, and scenarios that resonate with the experiences of diverse founders [

81,

82]. AI-powered simulations allow entrepreneurs to practice high-stakes decisions in risk-free environments, from investor negotiations to multi-stakeholder management, building both competence and confidence.

Hypothetical Case: Jennifer Chen, San Gabriel Village E-Commerce

Create a hypothetical case of a first-generation Chinese American entrepreneur using AI to enhance cognitive social capital and bridge cultural/market boundaries.

Context:

- -

E-commerce business serving ethnic markets seeking mainstream expansion

- -

AI as cognitive bridge between cultural frameworks

- -

Demonstrate knowledge translation, narrative alignment, cultural intelligence

- -

Show how AI enables maintaining authenticity while accessing broader markets.

Requirements:

- -

Age 25–35, bilingual/bicultural background

- -

Specific AI applications: bilingual content, influencer discovery, demand forecasting

- -

Use RAG, marketplace APIs, A/B testing automation

- -

Show revenue growth, retail expansion, community multiplier effects

- -

Demonstrate cultural translation without authenticity loss.

Jennifer Chen, a 28-year-old first-generation Chinese American, operated an e-commerce business selling Asian beauty products. While her bilingual, bicultural background helped within ethnic markets, scaling beyond the community required cognitive alignment with mainstream retail practices. AI tools provided cross-cultural market intelligence, identified micro-influencers bridging ethnic and mainstream markets, optimized supply chains, and translated business concepts across cultures. Within two years, revenue grew from USD 200,000 to USD 3.2 million, she expanded to 15 retail locations and launched an incubator supporting 10 other Asian American beauty entrepreneurs. AI facilitated cognitive social capital by enabling Jennifer to act as a translator across diverse stakeholder groups without sacrificing authenticity.

Process details: Jennifer combined bilingual product copy generation, influencer discovery, and demand forecasting. She grounded model outputs in her product catalogs and order histories (RAG), used AI to shortlist micro-influencers bridging ethnic and mainstream markets, and automated A/B tests for creative variants. These steps are implementable with current tools (e.g., model-plus-RAG, marketplace APIs, and automation).

Proposition 3. AI co-creation through enabled knowledge sharing, translation, and cultural intelligence tools will enhance cognitive social capital by facilitating shared understanding across diverse stakeholder groups, enabling women and minority entrepreneurs to bridge cognitive gaps that have traditionally limited their access to resources and opportunities.

This proposition focuses on the cognitive dimension of social capital, the shared meanings and understandings that enable effective collaboration and opportunity recognition AI serves as a cognitive bridge, helping entrepreneurs translate across different business paradigms and cultural frameworks. Women and minority entrepreneurs using AI translation and narrative alignment tools are predicted to communicate their value propositions more effectively to mainstream investors and customers while maintaining authentic connections to their core markets and values. Success in narrative alignment will be reflected in positive outcomes such as progression to due diligence, callback rates, funding success, and enhanced entrepreneurial confidence.

AI-facilitated development of shared mental models also improves team performance in diverse founding teams. Teams leveraging AI to surface and reconcile assumptions and perspectives are predicted to make faster decisions, experience fewer conflicts requiring external mediation, and report higher satisfaction, particularly in teams with greater demographic and cultural diversity. Cultural intelligence enhancement through AI reduces the cognitive burden of cross-cultural operations. Minority entrepreneurs employing AI-guided cultural intelligence tools are expected to enter new markets more efficiently, form international partnerships more successfully, and report lower stress in cross-cultural business interactions.

Testing this proposition may involve content analysis of pitches and business communications to assess alignment between entrepreneurial messaging and stakeholder expectations. Surveys can capture perceived understanding and alignment across stakeholders, while team performance metrics and cross-cultural business outcomes provide objective measures of cognitive social capital enhancement. Boundary conditions include the entrepreneur’s AI literacy, the accuracy and representativeness of input data, the cultural sensitivity of algorithmic design, and the rapid evolution of AI tools, which may render specific technical recommendations outdated.

3.5. Equity Outcomes: AI as a Catalyst for Inclusive Entrepreneurship

AI democratizes equity by enabling bias-resistant investor matching, providing access to non-traditional funding channels, and facilitating real-time negotiation support. These interventions mitigate systemic disadvantages in capital, mentorship, and knowledge, transforming social capital from an exclusionary resource into an inclusive enabler of opportunity [

38,

39,

81]. By simultaneously enhancing structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, AI functions as both an equity-leveling mechanism and a generator of sustained entrepreneurial advantage.

The integration of AI into entrepreneurial practice represents a paradigm shift in the generation, distribution, and strategic application of social capital. Strengthening structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions in a coordinated manner, AI democratizes access to networks, mentorship, and knowledge, directly addressing the compounded disadvantages faced by women and minority entrepreneurs. Beyond equity, AI generates distinctive capabilities that confer sustained competitive advantage, enabling underrepresented founders to leverage resources, insights, and relationships previously inaccessible. In this dual capacity, AI emerges not merely as a technological tool but as a strategic enabler of inclusivity and innovation, redefining the landscape of entrepreneurial opportunity in the 21st century.

Drawing on the three Los Angeles hypotheticals, we observe that AI interventions cumulatively improved financial, social, and cognitive resources. Maria Rodriguez accessed previously unreachable markets and networks; Keisha Williams established high-trust relationships and expanded investor and partner networks; Jennifer Chen translated community knowledge into mainstream business opportunities. Collectively, these outcomes illustrate how AI-mediated social capital reduces systemic inequities and produces sustained advantages.

Proposition 4. AI enhanced social capital across structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions will improve access to funding, mentorship, and entrepreneurial knowledge for women and minority entrepreneurs, resulting in greater social equity in entrepreneurial ecosystems.

This proposition predicts that the cumulative effect of AI-enhanced social capital will produce measurable improvements in entrepreneurial equity. The interaction among structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions generates multiplicative rather than merely additive effects; entrepreneurs who develop stronger network structures through AI can leverage these connections more effectively through enhanced relational trust and cognitive alignment. While each dimension captures a distinct mechanism through which AI reshapes opportunity, their true significance emerges in combination. Women and minority entrepreneurs rarely encounter disadvantages along a single dimension; instead, structural exclusion, relational bias, and cognitive misalignment compound to create persistent barriers to funding, mentorship, and knowledge access. AI’s transformative potential lies not only in strengthening each dimension in isolation but also in reinforcing them simultaneously, converting social capital from an exclusionary privilege into an inclusive enabler.

We anticipate the following outcomes.

Funding: Entrepreneurs using comprehensive AI tools are expected to achieve higher application success rates, larger funding amounts, better terms, and reduced time to funding. The funding gap between women and minority entrepreneurs and their white male counterparts is predicted to narrow more rapidly in ecosystems with high AI adoption, particularly for those leveraging AI across all three dimensions of social capital.

Mentorship: AI-augmented mentorship is anticipated to increase access, relevance, and frequency of guidance. Women and minority entrepreneurs using these systems are likely to receive more culturally and contextually appropriate advice, partially compensating for the scarcity of mentors from similar backgrounds.

Knowledge Acquisition: AI-powered learning and simulation tools accelerate entrepreneurial learning curves, enabling faster progression through key milestones, including first sale, break-even, and scaling. Entrepreneurs using AI are predicted to report greater confidence, fewer costly mistakes, and improved decision-making.

Venture Survival and Growth: Five-year survival rates and growth metrics—including revenue, employment creation, and market expansion—are expected to improve disproportionately for women and minority entrepreneurs using comprehensive AI support.

Testing this proposition requires longitudinal cohort studies comparing entrepreneurs with varying levels of AI engagement, assessing access to funding, mentorship, knowledge, and network inclusion. Careful attention to selection effects is essential to ensure validity. Outcomes are contingent on comprehensive AI adoption, regulatory support, and ecosystem engagement. Potential implementation challenges include algorithmic bias, digital divides, and societal resistance, which may limit the full realization of AI’s equity-enhancing potential.

3.6. Competitive Advantage: AI as a Strategic Differentiator

AI’s influence extends beyond equitable access to social capital, encompassing the creation of sustained competitive advantage. When deployed strategically, AI can generate rare, valuable, inimitable, and non-substitutable capabilities, consistent with the resource-based view of the firm [

16,

28]. AI-enhanced decision-making enables entrepreneurs to process complex data, detect hidden patterns, and compensate for the absence of costly consultants or large analytics teams [

12]. Generative AI accelerates innovation cycles, shortening the path from ideation to market testing and allowing underrepresented founders to demonstrate progress and secure investor interest more quickly [

83]. Personalization at scale allows small ventures to deliver experiences previously restricted to resource-rich incumbents, from customized product recommendations to AI-mediated customer support [

84].

The competitive advantage derived from AI arises not from generic adoption but from context-specific application. Training AI models on proprietary datasets, leveraging culturally informed inputs, and employing sophisticated prompt engineering produces capabilities that are difficult to replicate [

85,

86]. Early adopters accumulate path-dependent knowledge of effective integration strategies, creating tacit assets resistant to imitation [

87]. Network effects further amplify this advantage, as AI-enhanced relationship building generates feedback loops that improve AI performance and deepen social capital, producing cumulative benefits inaccessible to late movers [

88].

The Los Angeles hypotheticals illustrate these dynamics. Maria Rodriguez leveraged AI to optimize supply chains, forecast demand, and align her offerings with sustainable fashion trends, creating operational and market intelligence that competitors could not easily replicate. Keisha Williams combined technical insight with AI-enabled hybrid networks, bridging Silicon Beach investors and South LA health networks to identify underexplored opportunities. Jennifer Chen acted as a cognitive bridge across cultural and market boundaries, using AI to scale distribution and marketing while maintaining authenticity to her community. These examples demonstrate how AI can transform underrepresented entrepreneurs into innovation leaders, simultaneously enhancing equity and strategic differentiation.

Proposition 5. Women and minority entrepreneurs who develop AI co-creation as a strategic capability through intentional customization, domain-specific training, and deep organizational integration will achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, overcome resource constraints and positioning themselves as innovation leaders.

This proposition extends beyond equity to examine competitive advantage. We predict that women and minority entrepreneurs who strategically leverage AI are predicted not merely to achieve parity with established competitors but to develop unique advantages derived from combining AI capabilities with distinctive insights and market positions.

Domain-specific AI customization will create difficult-to-replicate capabilities. Entrepreneurs who train AI models on their proprietary market knowledge, customer relationships, and culturally informed inputs will create difficult-to-replicate capabilities. These customized AI tools will enhance performance in their specific contexts, resulting in higher customer satisfaction, better product–market fit, and more efficient operations than competitors using generic AI tools or no AI.

Combining lived experience with AI capabilities produces unique value propositions. Women entrepreneurs leveraging insights into underserved female consumer needs through AI-driven product development and marketing will identify opportunities competitors may overlook. Minority entrepreneurs scaling culturally authentic products using AI will achieve higher customer loyalty and word-of-mouth effectiveness than mainstream competitors attempting to serve these markets.

Early AI adoption and deep integration will also create advantages. Entrepreneurs who are early adopters of AI in their specific sectors will develop tacit knowledge and organizational capabilities that provide sustained advantages even as AI tools become more widely available. These entrepreneurs will show consistently superior performance metrics compared to later adopters, with the advantage persisting over time.

Network effects from AI adoption will create self-reinforcing advantages. Stronger networks attract better talent, partners, and investors, which in turn generate more data and resources for further AI enhancement. This virtuous cycle positions women and minority entrepreneurs as innovation leaders and catalysts within entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Validation of this proposition requires identifying and tracking entrepreneurs who strategically adopt AI versus those who use it superficially or not at all. Performance comparisons should control for industry, market, and founding team characteristics. Case studies can illuminate mechanisms through which AI produces competitive advantage, while quantitative analyses can measure magnitude and persistence. Competitive advantage is contingent upon early adoption, unique data access, and deep organizational integration. Effectiveness may diminish as AI tools become commoditized, and cultural, legal, or regulatory contexts may moderate outcomes.

3.7. Boundary Conditions and Moderating Factors

The propositions developed in this study operate within several critical boundary conditions that shape the impact of AI on social capital and entrepreneurial outcomes. First, access to digital infrastructure is foundational; without reliable internet connectivity, computing resources, and access to contemporary AI platforms, the potential benefits of AI are severely constrained. Second, AI literacy is necessary for effective adoption, as entrepreneurs require a foundational understanding of AI capabilities, limitations, and ethical implications to use these tools strategically. Third, ecosystem support—including investors, partners, accelerators, and incubators—is essential for AI tools to yield meaningful outcomes, particularly in contexts where mentorship, resource networks, or knowledge flows are limited. Fourth, the regulatory environment mediates the effectiveness of AI adoption. Overly restrictive policies may constrain innovation and experimentation, while absent or inadequate governance can exacerbate inequities or allow harmful algorithmic practices to persist. Fifth, the design, transparency, and fairness of AI algorithms constitute a key boundary condition. Algorithmic bias, lack of interpretability, or culturally insensitive model assumptions can diminish the effectiveness of AI-mediated interventions, while careful attention to ethical AI design, auditability, and contextual adaptation enhances trust, usability, and equitable outcomes. Finally, cultural and institutional context influences how AI-mediated interactions, trust-building, and cognitive alignment are realized; highly traditional or relationship-based business cultures may reduce the efficacy of AI tools in network expansion, mentorship facilitation, or knowledge translation. Collectively, these conditions underscore that AI’s potential to enhance equity and generate competitive advantage is contingent not solely on technology itself, but also on infrastructure, education, institutional support, algorithmic integrity, and socio-cultural alignment.

4. Discussion

The illustrative Los Angeles hypothetical cases—Maria Rodriguez in East LA manufacturing, Keisha Williams in South LA wellness tech, and Jennifer Chen in San Gabriel Valley e-commerce—demonstrate the mechanisms through which AI enhances structural, relational, and cognitive social capital, while revealing critical boundary conditions shaping its effectiveness. Collectively, these examples illustrate how AI functions not merely as a technological tool but as a strategic enabler of social equity, competitive advantage, and sustainable entrepreneurship.

4.1. AI as an Equity-Leveling Mechanism

Across all three cases, AI enabled underrepresented entrepreneurs to overcome structural disadvantages in network access, mentorship, and knowledge translation. Maria’s AI-powered market mapping bridged geographic and social divides, facilitating weak ties that were previously inaccessible. Keisha’s AI-enabled investor matching and network expansion allowed her to navigate a predominantly white, male tech ecosystem. Jennifer’s AI-mediated cognitive bridging facilitated expansion beyond ethnic markets while maintaining authenticity. These examples support Proposition 4, which predicts that cumulative AI-enhanced social capital can produce measurable improvements in entrepreneurial equity.

Importantly, the cases reveal that AI’s impact is multiplicative rather than additive. Maria’s network expansion (structural) was amplified through AI-assisted communication (relational) and narrative framing (cognitive), accelerating growth and resource acquisition. Similarly, Keisha’s hybrid networks strengthened by AI facilitated both mentorship access and investor engagement, illustrating the synergistic effects of AI across social capital dimensions.

4.2. Cross-Cutting Insights

Several patterns emerge from the Los Angeles hypotheticals:

Geographic Bridging: AI mitigates physical and structural isolation, connecting entrepreneurs from resource-poor neighborhoods to mainstream networks. Virtual connections and cognitive alignment reduce the determinative role of physical distance in accessing resources.

Cultural Translation: AI supports entrepreneurs navigating multiple cultural contexts simultaneously, maintaining authenticity within home communities while accessing mainstream markets. Jennifer Chen’s experience illustrates how AI-assisted translation of business practices across cultural contexts preserves relational trust and market relevance.

Network Intersection Advantages: AI helps entrepreneurs leverage positions at the intersection of multiple networks, transforming marginality into strategic advantage. This aligns with propositions regarding structural and relational social capital enhancement.

Community Wealth Building: Success was leveraged to support other entrepreneurs, creating multiplier effects. AI facilitated the transfer of knowledge, mentorship, and networks, amplifying social impact.

Incremental Implementation: AI adoption was most effective when applied strategically and incrementally to address specific pain points, demonstrating that equity outcomes depend on thoughtful deployment rather than mere technology access.

4.3. Theoretical Implications

Our framework extends our current understanding of entrepreneurship, technology, and social equity in several ways. First, by reconceptualizing AI as a co-creation partner rather than merely a tool, we challenge traditional boundaries between human and technological agency in entrepreneurship. This perspective redefines entrepreneurial agency, influencing how we theorize opportunity recognition, resource mobilization, and value creation [

10,

11].

Second, the integration of social capital theory with RBV reveals how technological capabilities can simultaneously address equity gaps and create competitive advantages. This challenges the implicit assumption in much of the entrepreneurship literature that equity and excellence represent trade-offs. Women and minority entrepreneurs who strategically leverage AI can achieve superior performance precisely because their unique perspectives and market insights, combined with AI, create capabilities that are difficult-to-replicate [

16].

Third, the three-dimensional analysis of social capital enhancement through AI provides a more nuanced understanding of how technology affects entrepreneurial networks. Structural, relational, and cognitive enhancements through AI provide a nuanced understanding of digital transformation, illustrating how technology reshapes relationships, trust, and shared understanding across diverse entrepreneurial contexts. Finally, our analysis also contributes to critical entrepreneurship studies by examining how technology can either reproduce or disrupt existing power structures. While bias in historical data risks perpetuating inequities, intentionally designed AI can disrupt traditional gatekeeping and democratize access to resources [

14,

15]. Technology’s impact on equity is not predetermined but contingent on design choices, governance structures, and implementation strategies.

4.4. Practical Implications

The findings offer actionable guidance:

- -

Entrepreneurs: Effective AI use requires strategic thinking about which capabilities to develop, how to integrate AI with unique insights, and how to maintain authenticity. AI should be approached as a capability to cultivate rather than a solution to purchase. Strategic adoption—domain-specific customization, proprietary applications, and early-mover advantages—enables entrepreneurs to overcome barriers and gain competitive edge.

- -

Investors and financial institutions: Investors should value AI integration in due diligence, recognizing how AI can compensate for resource constraints and create distinct advantages. They must also ensure their own AI use does not perpetuate bias [

89]. Sophisticated AI adoption signals both technical skill and strategic foresight, warranting particular attention in investment decisions.

- -

Support organizations: Accelerators, incubators, and SBDCs should implement comprehensive AI literacy programs that address strategy, ethics, and cultural adaptation. AI can also enhance organizational effectiveness by identifying promising entrepreneurs, matching resources, and tracking differential outcomes to ensure equity in program impact.

- -

Policymakers: Digital infrastructure investment, AI literacy education, and equitable governance frameworks are critical. Policy interventions should simultaneously address access, capability development, and algorithmic fairness while fostering innovation that benefits underrepresented entrepreneurs.

4.5. Implications for Sustainability

The intersection of AI, entrepreneurship, and equity has profound implications for sustainable development. Women and minority entrepreneurs often prioritize social and environmental sustainability alongside financial returns, suggesting that fostering their success through AI could accelerate progress toward sustainable development goals [

90]. The Los Angeles hypothetical cases demonstrate this connection—Maria’s sustainable manufacturing, Keisha’s health equity focus, and Jennifer’s support for other entrepreneurs all seek to create value beyond pure financial returns.

AI’s potential to democratize entrepreneurship could contribute to more inclusive economic growth, reducing inequality while fostering innovation. However, this requires attention to the environmental costs of AI systems themselves, including energy consumption and electronic waste. Sustainable implementation of AI in entrepreneurship must balance equity benefits with environmental considerations. The framework also suggests that AI could enable new forms of sustainable entrepreneurship by reducing resource requirements for venture creation and growth. Virtual operations, AI-enabled efficiency, and digital market access could allow entrepreneurs to create significant value with smaller environmental footprints. This could be particularly important for entrepreneurs in resource-constrained contexts who must achieve more with less.

4.6. Future Research Directions

This paper opens several promising avenues for future research that could deepen understanding of AI’s role in fostering entrepreneurial equity:

- -

Longitudinal Impact Cohort Studies tracking cohorts of entrepreneurs AI adoption and long-term equity outcomes;

- -

Intersectional Analyses examining how AI impacts vary across gender, race, and entrepreneurial contexts;

- -

Comparative International Research exploring how policy and institutional environments shape AI’s equity effects;

- -

Technical Innovation Research focused on fairness-aware, privacy-preserving, and bias-mitigating AI systems co-designed with affected communities;

- -

Business Model Innovation Studies exploring sustainable models for developing and deploying equity-focused AI tools;

- -

Ecosystem evolution research examining how AI adoption reshapes entrepreneurial networks, intermediaries, and power dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates that AI has the potential to transform entrepreneurial ecosystems by simultaneously promoting social equity and competitive advantage for women and minority entrepreneurs to enhance their venture success. Through our theoretical framework and propositions, we suggest that AI can enhance social capital across structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, providing mechanisms to overcome historical barriers in funding, mentorship, and knowledge acquisition.

By reconceptualizing AI as a co-creation partner rather than a mere tool, we highlight how human–AI collaboration can redefine entrepreneurial agency, enabling underrepresented entrepreneurs to leverage their unique perspectives and market knowledge to generate distinctive value in their ventures. The integration of social capital theory with the resource-based view further illustrates that equity and excellence do not need to be trade-offs; strategic AI adoption can produce rare, inimitable capabilities that both close resource gaps and create sustainable competitive advantage. Theoretically, this work advances social capital theory in three ways. Firstly, it reframes social capital from a static stock of ties into a dynamic, AI-mediated process of activation, where dormant relationships and latent knowledge are mobilized rapidly under changing conditions. Secondly, it extends the notion of embeddedness by showing how AI acts as a mediating actor that lowers barriers to elite networks and reshapes the relational terrain for excluded groups. Thirdly, by centering equity and sustainability outcomes, this study introduces an intersectional lens that moves social capital theory beyond efficiency toward a richer account of inclusion and systemic transformation. Our framework also contributes to the resource-based view of the firm by viewing AI not only as a valuable resource but by considering that AI-enabled social capital constitutes a dynamic capability whose rarity and inimitability emerge not from the technology itself but from intentional customization, early adoption, and integration with entrepreneurs’ lived experiences. In this way, equity-enhancing practices do not detract from competitive advantage but instead generate it, showing that inclusivity can be a foundation of differentiation. Moreover, by emphasizing co-creation, we move RBV beyond resource possession toward resource generation, where strategic advantage is achieved through ongoing interaction between entrepreneurs, AI systems, and ecosystems.

Our propositions provide testable predictions and actionable insights for multiple stakeholders. Entrepreneurs are encouraged to cultivate AI capabilities strategically, combining domain-specific knowledge, proprietary customization, and early adoption to maximize impact. Investors and support organizations are urged to recognize and nurture AI-enhanced ventures while mitigating potential algorithmic biases. Policymakers play a critical role in ensuring equitable access to digital infrastructure, AI literacy, and governance frameworks that support inclusive innovation.

Beyond economic outcomes, AI-enabled entrepreneurship carries significant implications for sustainability. By reducing resource requirements, enabling more efficient operations, and supporting ventures with social and environmental objectives, AI can foster inclusive and environmentally responsible entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Despite these opportunities, realizing AI’s full potential requires attention to contextual factors, including digital infrastructure, AI literacy, ecosystem support, cultural norms, and regulatory environments. Future research should validate the proposed mechanisms through longitudinal, intersectional, and comparative studies while exploring innovations in fairness-aware AI, sustainable deployment models, and ecosystem evolution.

This framework contributes to social sustainability by reconceptualizing AI-enabled entrepreneurial equity as a mechanism for systemic change rather than individual advancement alone. By democratizing access to social capital across structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, AI has the potential to address persistent inequities that undermine progress toward UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly gender equality, decent work, and reduced inequalities. The proposed approach moves beyond traditional interventions to enable community wealth building and multiplier effects, as demonstrated in our Los Angeles hypotheticals where entrepreneurial success created cascading benefits including local employment growth, knowledge transfer, and support for additional underrepresented entrepreneurs. While engaging critically with scholarship that questions entrepreneurship’s capacity to deliver equitable outcomes, we argue that intentionally designed AI can disrupt traditional gatekeeping mechanisms and create more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystems. However, realizing these social sustainability benefits requires addressing boundary conditions including digital infrastructure access, AI literacy, and algorithmic bias. The framework’s social sustainability contribution lies in proposing scalable mechanisms for transforming entrepreneurial ecosystems from exclusionary structures into inclusive enablers of community development, though empirical validation remains necessary to confirm these theoretical predictions and their broader societal impact.

In sum, this work positions AI not only as a tool for efficiency but as a strategic capability that advances both theory and practice. By intentionally designing and deploying AI with equity and sustainability in mind, entrepreneurial ecosystems can evolve into more inclusive, resilient, and impactful systems of innovation.