Abstract

Elite capture, a power structure problem involving rent-seeking, hinders sustainable water resources management. Governments play crucial roles in instilling public legitimacy in water governance, a common-pool resource that benefits from cooperative solutions such as pilot competitions, co-monitoring, and inter-agency coordination. A study of South-to-North Water Diversion Projects in China showed how, when governments outsource small projects to local sub-contractors, a method named moderate supervision (ruo jiandu) can enable effective oversight, which is superior to a bidding model with strict supervision (qiang jiandu). The concept of moderate supervision was initiated in 2023, before which most small projects had been left in a risky state with no supervision (ling jiandu). Analysis of a case in Shandong Yellow River Water Diversion Irrigation Area involved semi-structured in-depth interviews. Findings revealed that an elite-government-villagers tripartite spiral was composed of 3 dimensions reshaping a positive elite culture: first, a whitelist of qualified local contractors; second, co-monitoring of multiple stakeholders with influence exerted by a three-tier mobilization system; third, inter-agency coordination innovatively enabling smooth functioning between policy entrepreneurs of formal institutions and local social governance of informal ones. Policy implications to underscore real-world applicability are provided.

1. Introduction

Water has been the wellspring for the prosperity of agriculture and civilizations, yet it can also be the root cause of their decline. Management of water diversion projects, which redistribute resources from water-rich to water-scarce areas, is are vital man-made lifeline for the sustainability of human development [1]. Water diversion initiatives have been employed globally since time immemorial as a fundamental strategy for water governance. These endeavors entail the manipulation of hydrological systems through the process of channeling water as opposed to the mere containment of water. These initiatives are of a large-scale nature and address critical challenges, which include the mitigation of flooding and the management of drought, in addition to the implementation of agricultural irrigation and ecological restoration. Nevertheless, considering their considerable magnitude and social and environmental impacts, the historical legacy of such projects is frequently intricate and contested, signifying a dual potential for significant public benefit and considerable socio-economic cost [2].

As the world’s largest inter-basin water transfer project, the South-to-North Water Diversion (SNWD, nanshui beidiao) Project is designed to solve the problem of a lack of water in China’s northern plains, including cities like Beijing and Tianjin [3]. It does this by moving billions of cubic meters of water annually from the Yangtze River Basin in south China through three large canal systems: the Eastern, Central, and Western Routes. Shandong Yellow River Water Diversion Irrigation Area (SWDA), being a beneficiary of its Eastern route (ER-SNWD), is a significant regional component, managing and distributing this transferred water across Shandong Province’s intricate network of rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and rural communities to address local water scarcity. Research found that Shandong’s planned local water demand has been overestimated to be 1.5 Bm3 by 2020 and 3 Bm3 or so by 2030, with actual annual use at 0.5 Bm3. For end users, the diverted water only reached 0.2 Bm3. That created challenges of collecting the water fee, including a fixed annual access fee at 0.76 CNY/ton, mainly paid by the city government, and a volumetric charge at 0.78 CNY/ton, totaling 1.54 CNY/ton [4].

After nearly a decade, some of the challenges have been partially relieved. Firstly, the annual external water diversion increased approximately fourfold compared with the 2012 level. After the normal supply period from March to May, emergency water has been frequently replenished in autumn or winter on local requests [5]. Secondly, the diverted water price is comparatively low compared to the residents’ daily water price of 3.35 CNY/ton. Since 2020, SNWD has combined the water dispatching and operation with the Yellow River Water Diversion Project to Qingdao (yinhuang jiqing), the East Shandong Water Diversion Project from Qingdao to Weihai Section (jiaodong diaoshui), and the Xiashan Reservoir (xiashan shuiku, in Weifang City), integratively utilizing local water, diverted water, rainwater, and flood water, to reduce the total use cost. The volumetric charge of 0.24–3.37 CNY/ton takes into account the distance from the canal’s starting point to the end users in pricing consideration [6]. Thirdly, project management has been updated, regulated, and made more accountable. Since 2002, the government has facilitated management reform in water diversion projects [7]. Through continuous efforts, SWDA introduced four professional companies by 2020. It deployed 875 inspection and maintenance personnel across the entire 450 km open channel, 150 km pipeline, and closed channel, as well as 13 pump stations, over 190 sluice stations, and valve wells. This significantly improved management and maintenance efficiency, making solid progress in standardization [5].

Furthermore, monitoring is another crucial aspect of the water diversion work. From the provincial level, 13 manual water quality monitoring sections have been established, entrusting third-party testing institutions to conduct regular water quality tests three times a month. These tests include up to 35 indicators, such as algae in reservoirs. Since 2018, digital construction has accelerated monitoring work, with 2034 km of optical cables laid, over 3000 sets of transmission and network equipment with 2645 cameras, and 69,723 information points at 13 pump stations, 87 sluice stations, and 42 valve stations [5]. However, no matter how institutional infrastructure and technological supports are provided, large-scale water diversion projects are enabled by numerous micro-projects, budgeted under CNY 300,000 (USD 40,000 or so) or building areas of less than 300 m3 [8,9]. They act as the key links and control nodes for the dense networks of large-scale water diversion projects.

Micro-projects widely exist in rural areas, often mirroring the form and components of large-scale ones. To optimize project efficiency and costs, governments entrust local capable persons (bendi nengren, LCPs) as subcontractors [10]. With the establishment of public–private partnerships (PPPs), LCPs with expertise in construction can participate in the production of water diversion projects alongside the government. However, this also increases the risks resulting from a lack of monitoring, these being rent-seeking or elite capture, enlarging social disparity [11,12]. Previous studies have mainly focused on citizens or non-public actors. Still, the inequality and core–periphery structure emerging among the citizens might be another angle from which to perceive the common-pool resource (CPR) governance process. How to avoid the tendency of elite capture (jingying buhuo) has become a critical determinant for fulfilling the gigantic amount of micro-projects.

2. Beyond Capture: How to Partner with Local Elites?

Water, as a collective good, is characterized by rivalry of use and non-excludability in feasibility. Water diversion project management, as a kind of public service, requires high levels of cooperation, requiring the inputs and activities of citizens, especially the LCPs, in the delivery, together with the government [13]. The public, as both the consumers and producers of the CPR, investing their own capital in the public endeavor, could largely save costs with an individual sense of responsibility [14]. LCPs could be benign partners or evil gamblers, who are regarded as elites prone to capturing privately-owned interests from collectively owned property or processes [15,16]. When a small number of elites pursue power concentration, interest monopolization, or resource misappropriation [17,18], the government’s grassroots governance capacity erodes [19] and the risks of elite capture increase [20], bringing about hegemony in local social systems [21,22]. Furthermore, factions burst frequently when several elites exist in the same area [23].

2.1. Three Types of Elites

Generally, LCPs could be categorized into traditional (local), economic, and technocratic elites. Traditional local elites are privileged in kinship, leadership, or ownership. Some are born to control the collective decision-making rights, such as the caste elites in India [24]. Usually, they are recognized as prestigious figures who are resourceful in multiple sectors, proficient in promoting personal interchanges, establishing interactive relations, and facilitating structural homology [25]. They might be village heads, secretary-generals, or capable returnees, playing significant roles in diverse local networks [26]. They are good at alleviating communal interest conflicts [27], achieving synergies that officials cannot [28]. Economic elites are relatively better-off figures who can shape planning and resource allocation through lobbying, projects, or businesses. They are willing to contribute to community-based self-governance operations [29], sometimes even paying for public affairs out of their own pockets, significantly reducing government expenditure pressure [30]. In Peru, a mining company operated in a rural community, which smallholder farmers protested due to its negative implications for water quality and quantity [31]. In the Indo-British Rainfed Farming Project (IBRFP), funded by the British Department for International Development (DFID), chiefs and rich households in a tribe of western India, with a national fertilizer cooperative as local partner, made the poor and female marginalized [32]. Technocratic elites possess expertise, scientific knowledge, or administrative positions. They play the professional or technical roles of gatekeepers to push forward the procedures of development projects funded at home or abroad [33]. Because of their professionalism in specific areas, abrupt planning featuring simplification, abstraction, and standardization is often made without respecting indigenous knowledge or local metis [34]. Although the development projects did not reduce poverty effectively in Lesotho, their operational model was replicated globally. The reason was that local bureaucratic systems could thus be strengthened, albeit in an anti-politics approach [35]. In the digital era, surveillance capitalism [36] and climate sidelining [37] further enhance the non-political tendency of economic elites through attacking mass privacy, controlling opinions, or avoiding fundamental political action toward ecological progress.

2.2. From Root Causes to Solutions

Elite capture occurs due to structural power advantages, institutional design defects, interest conspiracy, and insufficient public engagement. As Mancur Olsen stated, collective action could not be possible unless such a gathering creates more gains than all the individual’s independent actions. If the marginal benefits are not lucrative enough, individuals leave or freeride. However, when marginal benefits are lucrative enough, some small interest groups might capture much more than other groups, bringing risks of monopoly [38]. Pierre Bourdieu added elements for capital, which should not only be in monetary forms but also cultural or social forms, creating both material and symbolic profits. This forms the trilogy of concepts—habitus, capital, and field—which defines the core of the theory of practice. Elites capture all forms of capital through field rules and personal advantages, while the habitus of farmers constrains their capacity for change and may cause resistance [39]. Ways to mitigate elite capture can be generally categorized into constraints, incentives, and monitoring.

To constrain, top-down exclusive institutions are designed to remove the elites from the playground who otherwise are always privileged at the center of the information or resource hierarchy. For example, in the targeted poverty reduction practices of the 2010s at 60 poor villages in Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan provinces of China, 25% of the registered poor households (jiandang lika hu) were local elites, who are better off than the average. A targeting error rate of 33% was found during the registration of poor households, among which the elite capture proportion reached 74% [40]. Regulations were later made to prohibit village leaders and rich households from being listed as the poor, setting the standardized on-site verification processes of first, enter (yi jin); second, observe (er kan); third, calculate (san suan); fourth, compare (si bi); fifth, deliberate (wu yi) [41]. Thus, what Bourdieu had mentioned about the reconstruction of elites’ habitus [42] was realized with the dynamics of cultural capital allocation rules [43].

Another solution is to provide incentives to the elites or small groups, such as capacity building, higher salaries, collective dividends, better-paid jobs, career reputation, or project tender qualifications. As has been done in climate governance under the Kyoto Protocol, selective incentives motivated actors to provide global public goods [37]. LCPs could contribute positively if they take sustainable governance as their unselfish public responsibilities, which could also be nurtured toward a pro-public-interests elite culture [44]. As stated above, in our paper, LCPs act as subcontractors of “micro-projects”, which means the water diversion projects’ tender qualifications are given as an incentive, while tapping their talents in civil engineering and maintenance. Then, monitoring work has to be launched at the same time since there exist risks of rent-seeking.

The third solution is just monitoring. As Elinor Ostrom had pointed out, the usual theoretical prediction is that people will not monitor each other, especially in a mutual way. Thus, it is worthwhile to explore how institutions have been created for individuals to commit themselves to monitoring their own conformance in a CPR situation [45]. Various practices have been practiced worldwide, with historical deposits that could even trace back to ancient times. Since the medieval period, the irrigation systems of Spanish huertas had been applied in three regions of Valencia, Murcia-Orihuela, and Alicante. Among these, Valencia employed traditional monitoring patterns among the Tribunal (water court), ditch-riders, syndics, and irrigators, under the management of the Executive Committee, which proved somewhat inefficient. On the contrary, Alicante, with better endowments, had been using a water rights market, with assigned and auctioned water usage quotas to be exchanged in scrips. Undoubtedly, Alicante was the most advanced among the three. However, the most stable, or sustainable, region was Murcia, where the agricultural commune randomly selected executive committee members and inspectors, with the water court functioning for centuries. With a very low amount of fines—only a few pennies at the most, with variable amounts depending on the gravity of the offense, economic conditions, and individual affordability—Murcia kept the infraction rate at 0.8%, meaning 200 recorded instances of water stealing took place in about 25,000 opportunities each year in the rotation irrigation system [46].

Like the Spanish huertas, the Filipino rural organization of zanjera served as a case study in the Global South. The most impressive achievement of zanjera was to mobilize large-scale labor without any direct monetary payment. Land around the tail of water canals (biang ti daga, or “sharing of the land”) and varied water usage rights (those who contributed 48% could get 55% of the water) served as incentives, allocated by the Maestro, or the local leader, as resources to mobilize. There were also sanctions or penalties for those who free-rode or shirked [47]. To achieve self-governance, effective monitoring requires measures that provide information and treatment by the relevant actors responsible for these issues.

2.3. What’s Neglected: The Role of Governments

Similarities between the monitoring of huertas and zanjera were that both gave the central role to small-scale irrigating communities, who made self-determinations on specific rules, officials elected, guarding systems, canals maintenance methods, etc., with organizations tailor-made to their indigenous knowledge, or metis, featuring substantial variations in respective local styles [48]. Needless to say, self-governance with minimal government intervention could reduce the state’s workload. However, the role of governments should not be neglected in the co-evolutionary scenarios that are more often seen in the Global South [49]. Generally speaking, monitoring of CPRs can be classified into three types. Strict supervision (强监督, qiang jiandu) refers to a top-down, high-intensity, and omnipresent mode of oversight and inspection by central government authorities. It involves setting strict, non-negotiable targets, employing rigorous auditing and inspection systems, and imposing severe penalties for non-compliance or corruption [50]. Zero supervision (零监督, ling jiandu): This describes a theoretical or failed state with a complete absence of effective government oversight, accountability, or regulatory enforcement. It is not an official policy but a critique of a situation where supervision has collapsed. Moderate supervision (弱监督, ruo jiandu): This is a more nuanced and strategic approach where the central government sets the broad framework and goals but allows lower-level governments, local communities, and market mechanisms significant autonomy in implementation. The state’s role shifts from direct controller to a facilitator and referee, intervening only when necessary.

Strict supervision provides clear responsibility, consistent execution, and a powerful deterrent effect. It is extremely efficient for attaining swift, unconditional compliance in circumstances such as large-scale infrastructure projects, as it institutes explicit objectives and a distinct chain of command for penalizing failure, including tender issuance, bid opening, construction procedures, and quality supervision, with strict requirements for public transparency [51]. This ensures the uniform implementation of policy across regions and serves as a useful anti-corruption tool by assuring consistent discipline. Nevertheless, these benefits are accompanied by considerable drawbacks. The model demands substantial administrative resources and continuous supervision, making it very expensive and unviable in the long run. In the water diversion discourse, due to the high transaction costs of the bidding model [52], it’s unfit for micro-projects [53]. Additionally, it limits local initiative and adaptability, leading officials to adopt a passive role as rule-followers who are reluctant to innovate or adjust policies to suit local contexts.

Zero supervision proffers potential advantages in terms of local autonomy and reduced expense. The allowance of maximum freedom allows for developing organic, tailored solutions and self-organization by local governments and communities with minimal central administrative expense. In principle, this absence of limitations might generate room for trial-and-error innovation. Nevertheless, these prospective advantages are eclipsed by substantial disadvantages [54]. The main problem arises when powerful individuals exploit their position to engage in corrupt practices, nepotism, and the theft of public funds. This results in considerable public detriment, encompassing ecological devastation, hazardous practices, and health emergencies. As a result, the national strategy becomes immaterial, leading to a complete administration breakdown.

Moderate supervision provides a balanced strategy for administration, blending central direction with regional adaptability. Its key strengths are in its capacity to achieve wide-ranging policy goals while allowing for local adaptation. By utilizing incentives and keeping an eye on things from all stakeholders’ viewpoints, it functions at a lower cost and in a more sustainable way than strict top-down methods. Additionally, its preventative character is about molding structures and routines, instead of simply rectifying breakdowns. But this approach is not without its challenges. Its execution is intricate, necessitating advanced organizational structures to establish productive motivation and oversight systems. In addition, there is a risk that local elites may manipulate processes for their own benefit despite a reduction in outright corruption. Furthermore, the efficacy of moderate supervision is contingent on substantial social capital, predicated on pre-existing levels of social trust, operational local institutions, and competent actors.

Before the moderate supervision mechanism, most LCPs have stealthily chosen to have zero supervision, engendering risks of rent-seeking and collusive tendering, creating perilous and severe challenges for project management. The mechanism of moderate supervision, found in SWDA, appears to serve as a tentative middle ground, coordinating entities between strict and zero supervision. It signifies the enhancement to transform the local elites from private benefit gainers to public mission advocates.

3. Case Selection, Methodology, and Analytical Framework

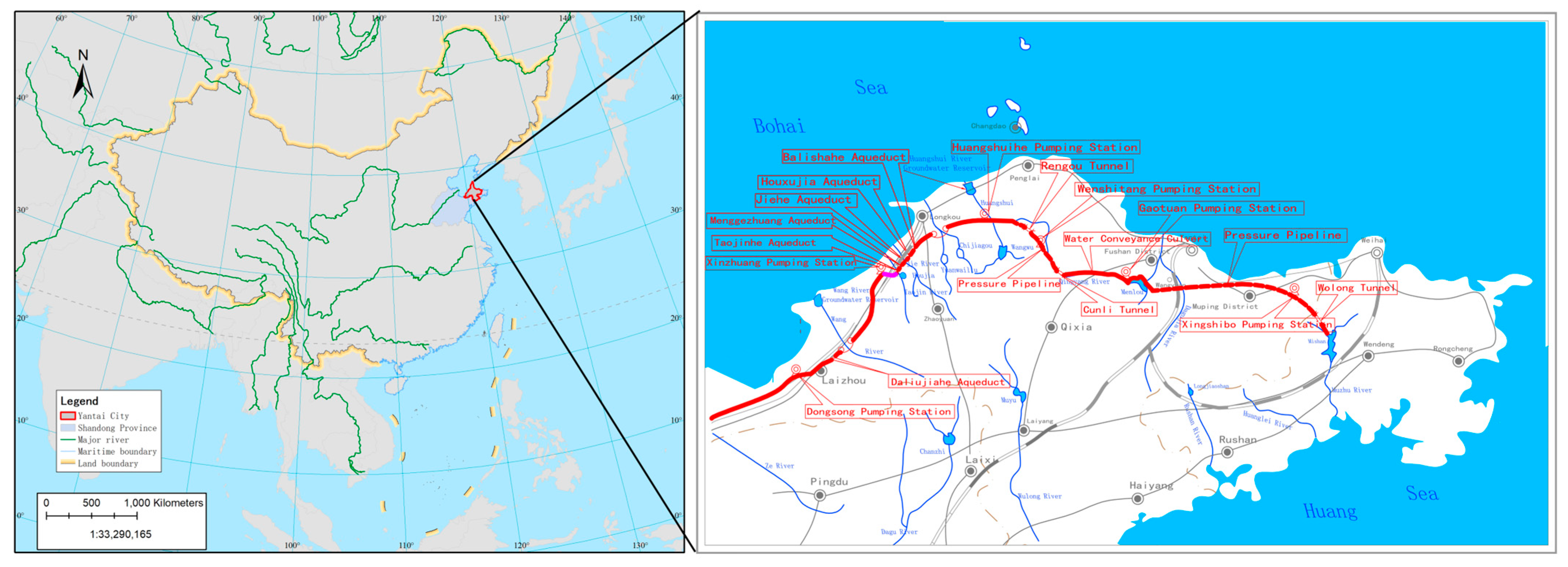

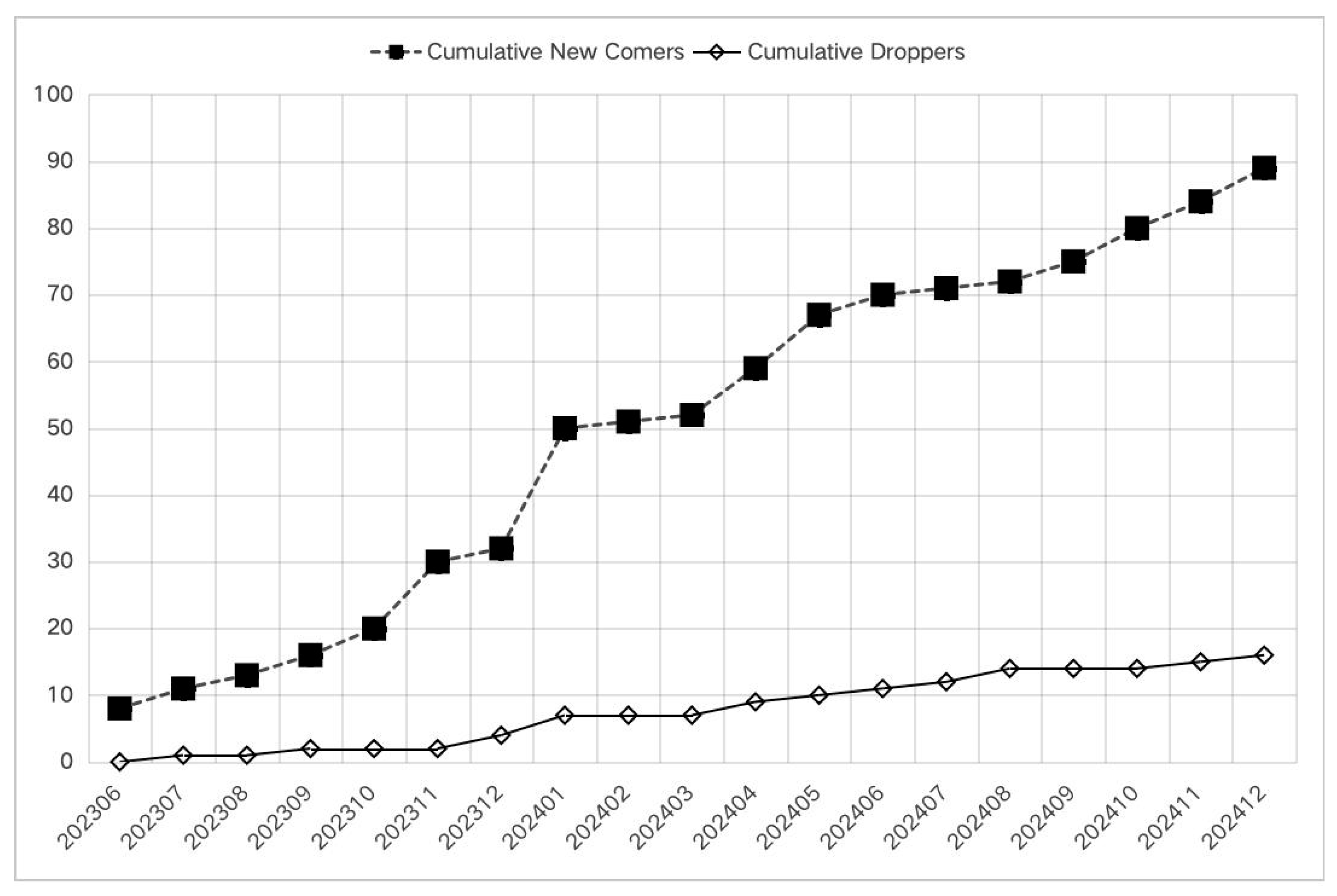

With a cumulative water transfer volume exceeding 76.7 BM3, the SNWD project has directly benefited 185 million residents and been pivotal in addressing spatial disparities in water resources distribution [55]. SWDA, as part of the eastern route of SNWD, was started in 2003, with water from the Yellow River and the Yangtze River diverted eastward with a canal 271 km long, passing through 255 rural villages [56] (See Figure 1 [57]).

Figure 1.

Location of SWDA in China and the canal construction route map [57].

The choice of SWDA as the centre of this examination was based on its exceptional aptitude for supervision systems in large-scale infrastructure projects. Shandong province exemplifies a pivotal scenario due to its acute water scarcity and traditionally elevated pollution levels, which heightened the significance and intensified interactions among other actors. The segment displayed exceptional capabilities in surmounting common difficulties, such as contamination management and community-wide collaboration, providing a favorable deviation from frequent setbacks and enabling the examination of effective moderate supervision in practice. Its functional maturity provided a more extensive history of demonstrable results and organizational practices. Importantly, the country village setting along the route is a typical environment susceptible to elite capture, making it a high-probability scenario for such issues and consequently a solid examination of how the project’s pioneering incentives, such as the whitelist system and three-tier rural mobilization framework, reduced these hazards. These distinctive governance characteristics, along with its empirical richness, rendered SWDA an ideal natural lab to examine how organized yet adaptable oversight can solve implementation challenges.

In early June 2023, a notice regulating micro-projects of SWDA was released [58], which achieved positive effects and was recognized, standardized, and institutionalized by the project administrators as a moderate supervision solution against the former zero supervision situation. Having been engaged in SWDA since January 2022, the authors launched semi-structured interviews of 51 respondents, including township and project staff members, LCP subcontractors, and villagers of the micro-projects, intending to examine how multiple stakeholders have accepted this mechanism and how it has taken effect (See Table 1), with each interview lasting for 0.5–1 h. The selection of the 21 villagers was conducted by implementing a random sampling methodology. This methodology was applied across five villages (L, T, X, Y, and W) from which LCPs had previously been drawn. The approach was devised to minimize selection bias and ensure that the demographic and socioeconomic composition of the community is accurately reflected. The incorporation of households exhibiting varying degrees of engagement with, and proximity to, the micro-projects and local officials ensures the capture of a more extensive range of perspectives within the sample. Self-governance practices in Ostrom’s analysis have been typical in voluntary cooperation and nested enterprises without much government intervention [59]. However, in the context of micro-projects, the budget makes third-party supervision impractical and not worth implementing. Thus, moderate supervision was innovated as a middle way.

Table 1.

List of the interviewees in this case analysis. Sources: made by the authors.

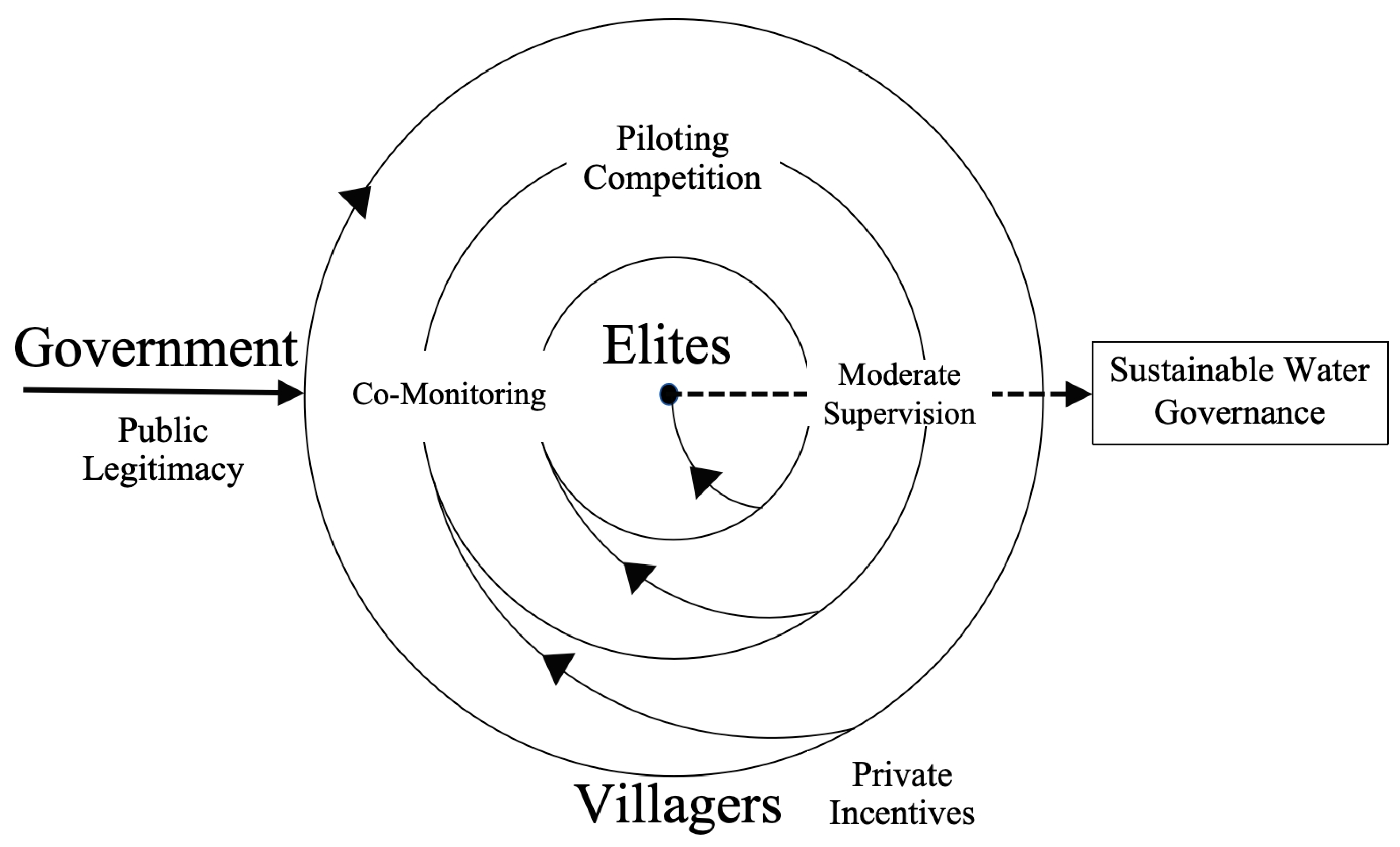

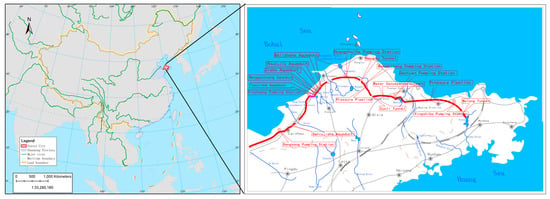

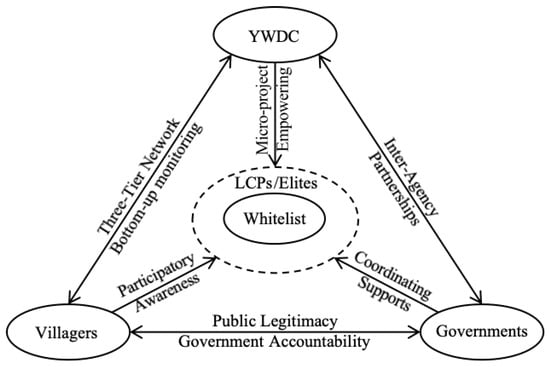

Inspired by Bourdieu’s theory of practices, we attempt to develop an elite habitus reconstruction analytical framework to analyze the moderate supervision rationale. As shown in Figure 2, without resorting to a strict supervision model with a third-party stakeholder, the local government of SWDA took the supervisor role to oversee the project construction behaviors of LCPs. At the very beginning, there were intense discussions and various opinions within SWDA about how to supervise the LCPs. People foresaw that it must be difficult to make LCPs self-disciplined enough to achieve high-quality performance in micro-projects.

Figure 2.

Elites’ habitus reconstruction analytical framework of “moderate supervision”. Source: drawn by the authors.

However, Director Wang of SWDA provided an analysis, as illustrated in Table 2, which serves as an evolutionary game theory model beyond just describing the situation to show how the strategies of different actors—like local elites deciding between working together and taking resources—change over time.

Table 2.

“Moderate Supervision” cooperation game model. Made by the authors based on typical rational cooperation and reputation game [60,61].

Based on incentives and the actions of other players, such as government agencies and villagers, this cooperation game model incorporates payoff matrices that assess the costs and benefits of behavioral options, thereby reflecting their systematic impacts. It illustrates how “some supervision” affects how people are paid, ensuring they work together effectively. In contrast, others may not perform as well or may not be suitable for long-term use. In the game theory model of moderate supervision, the best solution is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) that matches specific goals for the rules. The total maximum of payoffs or benefits is defined as Pareto Optimal [62], and the situation when all individuals seek selfish calculation without mutual communications is defined as the Nash Equilibrium, which is always a sub-optimal. The outcome where government trust is met with high-quality performance of LCPs yields the Pareto Optimal solution of Quadrant ① (1, 1). This result, with a total social payoff of “2,” is deemed optimal because it fulfils four critical criteria:

- (1)

- Economic efficiency is achieved by meeting project goals at lower costs and avoiding the wasteful sub-optimal equilibrium (−1, 0) from high-cost external firms (quadrant ③) or the LCPs’ unsatisfactorily performing suboptimal scenario of (0, −1) (quadrant ②).

- (2)

- System stability is achieved by avoiding the inactive status of (0, 0) (quadrant ④), where neither party has an incentive to deviate unilaterally—a Nash Equilibrium that allows both parties to be selfish without full communication.

- (3)

- Policy effectiveness is achieved by ensuring the reliable delivery of high-quality public goods of sustainable water management, mainly through the whitelist regime. It imposes reputational penalties for poor performance and offers transparent signals for trustworthy partnerships.

- (4)

- Through balanced payoffs that foster voluntary cooperation, social equity transforms isolated interactions into a repeated game, representing a self-reinforcing governance framework that aligns individual incentives with collective Pareto Optimal, ensuring cost-effective and sustainable production.

4. Case Analysis: Institutions and Effects of “Moderate Supervision”

Keeping “neither ‘strict’ nor ‘zero supervision’ works” in mind, SWDA took the primary monitoring responsibility for LCPs in the “moderate supervision” mechanism. However, public legitimacy is empowered in the elite LCPs through the creation of new mechanisms. Through a whitelist system with credits scored, the LCPs must abide by the clearly defined criteria. The elite’s habit of seeking private benefits will be transformed into a new one, characterized by avoiding private benefits to maintain their credit. As for the villagers, their former habitus of being “captured”, indifferent, or atomized has also changed to pursue more opportunities to express and to be known, to build capacity, or to get potential jobs due to the new regulations of “moderate supervision”. Elites need to provide villagers with more public benefits and welfare to receive positive feedback and win the peer competition. Thus, the former “core–periphery” relations between the selfish elites and atomized villagers [63] will be reconstructed into “mutual monitoring” relations in an upward spiral toward collective action of more efficient and sustainable water diversion project management, enabling each other for better performance.

Although LCPs are constrained and may complain, it’s worthwhile to issue this new monitoring regulation. It could help test which LCPs are more capable, leading them to dedicate themselves to the water diversion cause toward a win-win outcome.—Interviewee No. 24091301, Director Wang, SWDA Office

With the hypothesis mentioned above, specific mechanisms are examined in this part, and their effects are analyzed. The first concern regarding the “moderate supervision” component is the diversity of supervisory actors, which helps prevent the abuse of power and ensures consistent law enforcement.

4.1. Whitelist Indicators: Motivations for Piloting Competition

SWDA launched a whitelist system in its supervision framework, which screens and identifies LCPs with 20 indicators. According to Bourdieu’s definitions, they could be categorized into three types of capital (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Whitelisting criteria for LCPs to subcontract micro-projects.

Economic capital is immediately and directly convertible into money and could be institutionalized into property rights [64]. In the whitelisting criteria for LCPs to sub-contract micro-projects, about 19% of the indicators are allocated to this dimension, including bank deposits, debt ratio, project enforcement, equipment proficiency, etc.

Cultural capital indicates institutions relevant to educational qualifications [64]. About 33% of indicators, including professional qualifications and technical achievements, belong to this category. Experience of similar projects is regarded as a prerequisite for LCP registration. Projects under CNY 50,000 are open to newcomers. Projects between CNY 50,000 and 100,000 require sub-contractors with at least three successful experiences in previous projects. Projects over CNY 100,000 require sub-contractors to hold professional qualification certificates. The differentiated authorization mechanism ensures the competitiveness of project contracting and guarantees the reliability of major project implementation. Any major accident will make an LCP ineligible to be sub-contracted.

Social capital is made up of obligations or “connections” to be institutionalized in the form of a title of nobility [64]. It occupies the largest weight of 48% in all indicators, mainly related to community support, personal credibility, environmental responsibility, punctuality, dispute resolution capacity, compliance with contracts, etc. LCPs are supervised by the public big data, villagers, and project assessors. Suppose an LCP postpones the payment for migrant workers or its employees. In that case, they may be discredited by complaints, even terminating all subcontracting if the case is put on a public credit release website, such as https://www.creditchina.gov.cn/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

Besides, SWDA encourages peer reviews among LCPS, which was more challenging since elites are defined as competitors. SWDA opened complaint hotlines and email addresses to LCPs, and a specialized team was even started up to handle LCP-to-LCP complaints.

Once, a machine repair project started bidding. Both Mr. Liu and Sun are LCPs whitelisted. Sun had higher scores. However, Liu provided proof that Sun had used inferior construction materials in the past. SWDA investigated and verified Liu’s complaint. Sun lost credits, and Liu got the project.—Interviewee No. 24091303, Mr. Chen, Office staff member of SWDA

According to this whitelist system, the habits of elites to exploit and those of villagers to keep silent must be altered so that the best LCPs can be selected. Such a modelling mechanism, driven by public legitimacy, motivates all parties to conduct pilot competitions and engage in mutual monitoring (See Figure 2). It reallocates economic, cultural, and social capital by prioritizing LCPs’ relations with local governments and community members, followed by economic capital-based resources.

The whitelist system exhibits distinct characteristics tailored to the rural Chinese context, where decentralization often occurs within a framework of centralized political control [65]. Rather than adopting a democratic model, it operates as a state-supervised “franchise” system, with the devolution of implementation with centralized accountability [66]. For officially endorsed status, while ultimate authority remains with the central government, competition among local elites is introduced with rigorous performance measurement and a focus on serving citizens as “clients” [67]. It demonstrates a shift from input-based to outcome-based monitoring, emphasizing results rather than solely focusing on procedures [68]. It does not seek to dismantle existing power structures. Instead, it formalizes and channels the influence of LCPs, incentivizing them to contribute to public goods by making reputation a valued asset. This aligns with the Chinese “social governance” (shehui zhili) paradigm, which emphasizes stability and harmony through incorporating non-state actors into state-led governance systems [69].

This regime resonates with Ostrom’s CPR-governing principles, particularly the importance of graduated sanctions, matching rules to local conditions [45]. Integrating community feedback as a formal metric ensures alignment with local needs, even in the absence of electoral mechanisms, offering a model for how non-democratic regimes incorporate elements of accountability [70]. The use of a multi-dimensional scorecard mitigates the risk of manipulation and promotes holistic, sustainable development outcomes, reflecting broader insights about the importance of balanced performance indicators in governance [71]. While context-specific, the principles provide an adaptable template for improving governance and development outcomes elsewhere, particularly in settings where formal institutions are weak but social networks and reputational concerns are strong [72].

Whitelist implementation creates powerful incentives for excellence but also carries inherent risks. A primary limitation is the risk of exclusion for LCPs not included on the list. Excluded LCPs may encounter legitimacy deprivation and difficulties in securing funding, community support, or political favor, which could amplify existing disparities between well-endowed and marginalized communities. If protections are not in place, the government could exacerbate existing inequalities by creating new ones.

4.2. Three-Tier Mobilization Network: Igniting Monitoring Enthusiasm

Due to their fragmented geographical distribution and small volume scale, rural micro-projects often face monitoring challenges from formal institutions. However, farmers who reside at the front lines of the construction areas can provide real-time, first-hand, and rich information. Therefore, led by the Finance Section, through SWDA’s formal evaluation system, featuring “quarterly assessment (jidu ping), annual review (niandu he), and immediate withdrawal (jishi tui)”, public legitimacy is given to the villagers as grassroots supervisors.

SWDA established a supervision hotline (jiandu rexian) and suggestion boxes (yijian xiang) to extensively collect clues offered by farmers. It organizes water conservancy experts and villager supervisors to conduct random quality inspections every quarter on ongoing micro-projects in order to form the archives of whitelist scoring. Annually, the Audit Section of SWDA performs a comprehensive review of the utilization of funds. At the same time, a withdrawal channel with “yellow card” warnings and “red card” penalties is set up, serving as a mechanism for excellent LCPs to enter and for not-so-excellent LCPs to exit. Since adopting the grassroots supervising approach, 13 pieces of reporting information and 24 suggestions were received, effectively identifying latent problems. In 2024, 49 individuals were newly admitted to the whitelist and 12 individuals were removed due to failing to score 60.

If we are put on public notice for everyone to see, we’ll lose face if things go wrong. Let’s do our work well, ensure we don’t mess up, and become a laughingstock for everyone. If the villagers start gossiping about us from one to ten (yi chuan shi), ten to a hundred (shi chuan bai), that’ll be so embarrassing.—Interviewee No. 24122124, Mr. Xu, Farmer and LCP of Village X

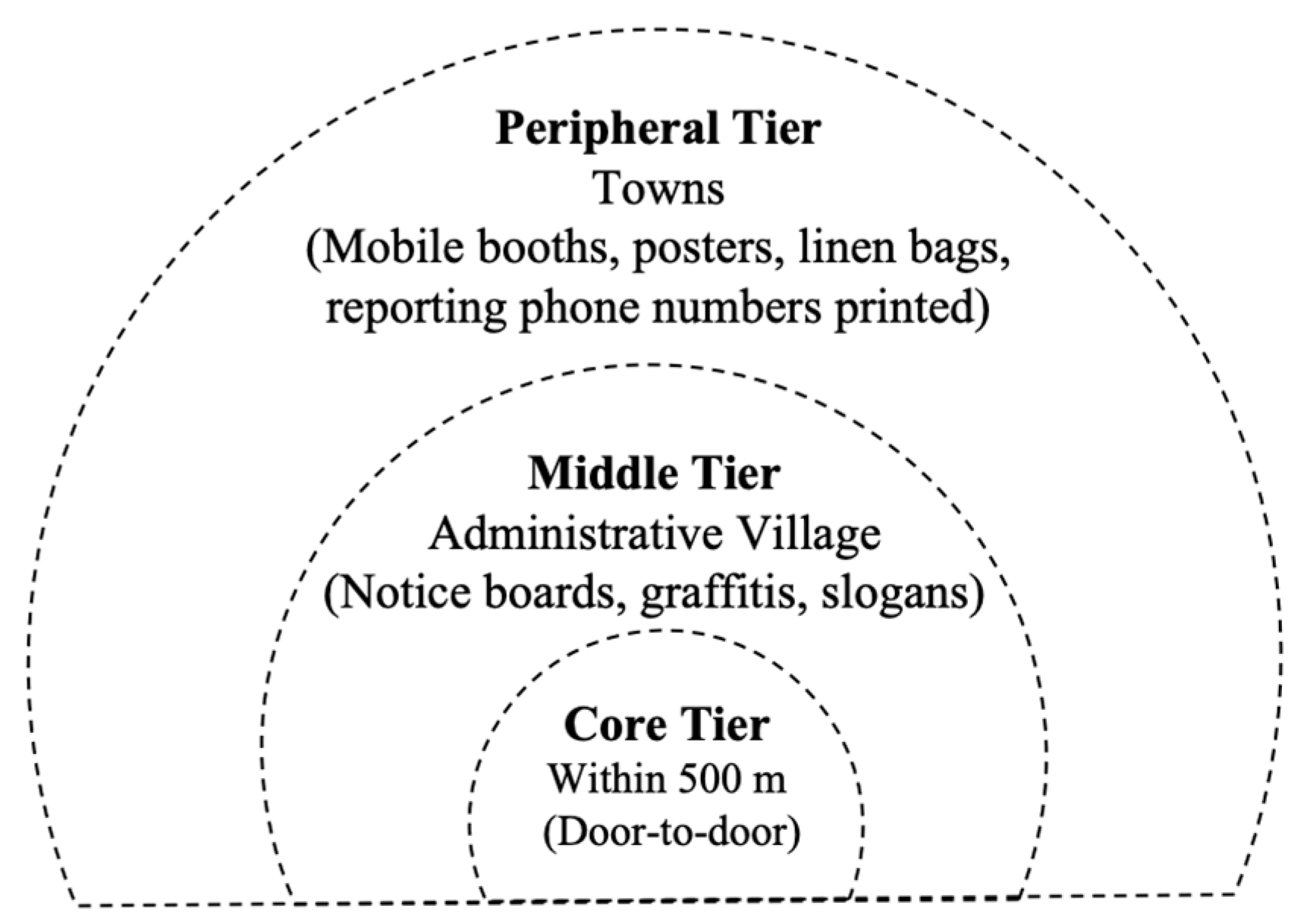

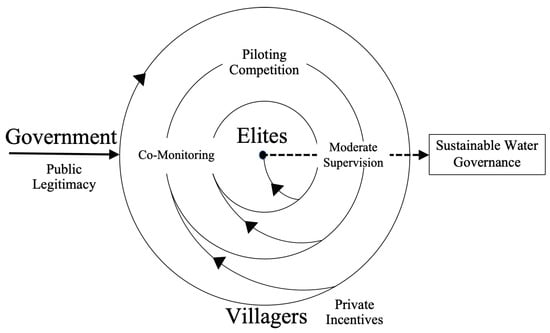

A “three-tier” mobilization network is made to inform the villagers systematically. For villagers living within 500 m of the project venue, or the core tier, who might not read or write, the staff adopt the “door-to-door” method to explain the monitoring rationale in detail. The middle tier covers the entire administrative villages, for which “notice boards” are used on the exterior walls of the village committees, public halls, and shops. Graffiti, sketches, and brand slogans are used to enable better understanding. The peripheral tier extends to densely populated areas in towns. Mobile booths are set up with customized posters and linen bags, and reporting phone numbers are printed to increase mass participation (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A “Three-Tier” mobilization network. Source: drawn by the authors.

The “three-tier” mobilization network enabled SWDA to enhance public awareness of the complexity of water diversion services and the importance of micro-project monitoring by reshaping the villagers’ former habitus with low costs and high efficiency.

Now we know how to monitor these projects. Before, when we wanted to complain, we didn’t know who to talk to. Last time I went to the market, the SWDA staff gave me a bag with the reporting hotline printed on it.—Interviewee No. 25012031, Mr. Tang, Farmer living along SWDA

Practical challenges, such as ensuring confidentiality, are also critical. If residents doubt the anonymity of their feedback, the system fails to capture honest assessments. This is related to the practical constraints of participatory institutions, which often require high levels of trust, technical capacity, and ongoing resources to function effectively [73,74]. Several measures are carried out to protect the informants and to verify through field tests. Firstly, the villagers are anonymized. Upon receiving a reporting call, only the issue’s date and summary are recorded. Secondly, a secure reporting environment is created. Boxes are placed in places with little traffic and no surveillance, where SWDA staff collect regularly. Thirdly, SWDA promises to check all the reported venues of each call. A division head (chuzhang) will be dispatched on-site if over three calls point to the same place.

We strive to ensure the public feels secure when filing reports. As most informants are highly vigilant about reporting LCPs and fear retaliation, providing them with a sense of safety during the voice calls is essential. Only in this way can we encourage them to participate in the monitoring.—Interviewee No. 24091605, Mr. Li, Engineering section staff member, SWDA

The three-tier mobilization network extends the literature on participatory governance [69] and co-production by moving beyond mere consultation to institutionalize citizens as essential partners in the supervision process. It operationalizes the concept that communities are not passive recipients but active agents in monitoring and ensuring accountability [70], directly addressing the challenge of making participation meaningful rather than symbolic by hardwiring community feedback into formal performance metrics.

Furthermore, this innovation offers a practical response to the elite capture problem [71] by “harnessing” rather than “fighting” elite power [72]. It exemplifies the interplay between formal and informal institutions [73], formally incorporating informal social capital, trust, and community standing into its evaluation criteria, creating a hybrid approach that leverages the legitimacy and structure of the state alongside the localized, nuanced information of the community.

It should be mentioned that the risk of metric manipulation or “teaching to the test” is ever-present, where LCPs might prioritize easily quantifiable outcomes over complex, long-term sustainability goals. Thus, persistent social pressures might pose a substantial barrier to genuine participation, leading to significant underreporting of grievances. This challenge resonates with James Scott’s concept of “public transcripts” [74]. In addition, community feedback as a core metric for evaluating local elites creates a self-reinforcing cycle of accountability that can be sustainable. The documented rise in public satisfaction and corresponding drop in formal complaints indicate that the system meets a fundamental need for responsive governance, which builds legitimacy and public “buy-in” as a critical foundation [75].

4.3. Inter-Agency Coordination with Other Departments

To highlight the importance of graduated sanctions and community-based monitoring, the system’s effectiveness may stem from its hybrid formal–informal design [76]. Devolving implementation responsibilities of “blocks” (kuai) at local administration, with the central-level horizontal “lines” (tiao) retaining authority over standard-setting and final accountability [77], it requires a pragmatic adaptation to the challenges of governing a vast and diverse country.

To enable informal institutions in governance to complement or compete with formal institutions, knowledge about tiao–kuai (条块) relations (关系, guanxi) and the central–local dynamic in China must be thoroughly familiarized [76]. SWDA, which belongs to the Ministry of Water Resources (shuili bu) of China, is horizontally parallel to sectors such as township bureaus of Development and Reform (DRC, 发改局, fagai ju), of Finance (财政局, caizheng ju), of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (农业农村局, nongye nongcun ju), of Ecology and Environment (生态环境局, shengtai huanjing ju), and so on. The moderate supervision regime represents an escape from the maze, integrating an otherwise informal social mechanism of “reputation” (a concept of kuai) into a formal management system (a concept of tiao), by using diverse feasible and useful governance tools.

Director Wang of SWDA contacted us, expressing his interest in cooperating with us to supervise the micro-projects. We thought it was fine. LCPs in the village will follow the financial arrangements, so it’s not difficult for us.—Interviewee No. 24112516, Mr. Zhang, Deputy Director,Economic Development Office, Town H

Policy entrepreneurship is necessary to establish an agenda for constructing the Government–SWDA communication channels. On one hand, SWDA signed a “Memorandum of Monitoring and Collaboration for Micro-projects” with town governments along the project corridor [78]. On the other hand, it continuously builds platforms. It conducts thematic training sessions, playing the dual role of gatekeepers for elite capture and facilitators in constructing a supervisory ecosystem.

4.4. Effects of the “Moderate Supervision” Mechanism

Empirical evidence supporting this approach is compelling. Data indicate a dramatic decrease in the micro-project modification rate, a significant rise in public satisfaction scores, and a substantial reduction in formal complaints. Furthermore, the rapid expansion of the LCP pool demonstrates the regime’s success in stimulating participation and broadening the base of governance actors.

This evidence suggests the whitelist system effectively addresses classic principal–agent problems by making agents (LCPs) accountable to both the principal (the state) and beneficiaries (the community). Compared to previous top-down or unregulated systems, it creates a dual alignment crucial for participatory development [79]. Firstly, it enhanced the project quality, shifting from compliance to excellence. Secondly, it improved efficiency by reducing bureaucracy and expanding competition. Thirdly, it strengthened community satisfaction by building trust through alignment.

Theoretical underpinnings of performance-based governance [80] regard this regime as a “career concerns” model, where LCPs are motivated to perform well to build a reputation and secure future projects. Moreover, it operationalizes the concept of co-production by formally integrating community feedback into the state’s monitoring apparatus, thereby blurring the line between service provider and beneficiary, leveraging local information for improved oversight [81].

Efficiency in decision-making improves with clearer personnel selection criteria. Pumping Station G, a deputy section-level administrative unit under SWDA, transports water to the largest reservoir in Yantai City. In the summer flood season of 2024, to prevent a significant surge of water into the central canal, Pumping Station G spontaneously raised CNY 100,000 and initiated a drainage micro-project, quickly selecting Mr. Gao, a whitelisted LCP, as the sub-contractor.

There are 3 LCPs in our village. In the past, it was complicated to decide which micro-project should be awarded. No matter who is chosen, the other two would complain. Now we have the whitelist, Mr. Gao is obviously the best.—Interviewee No. 24112210, Director Wei, Pump Station G

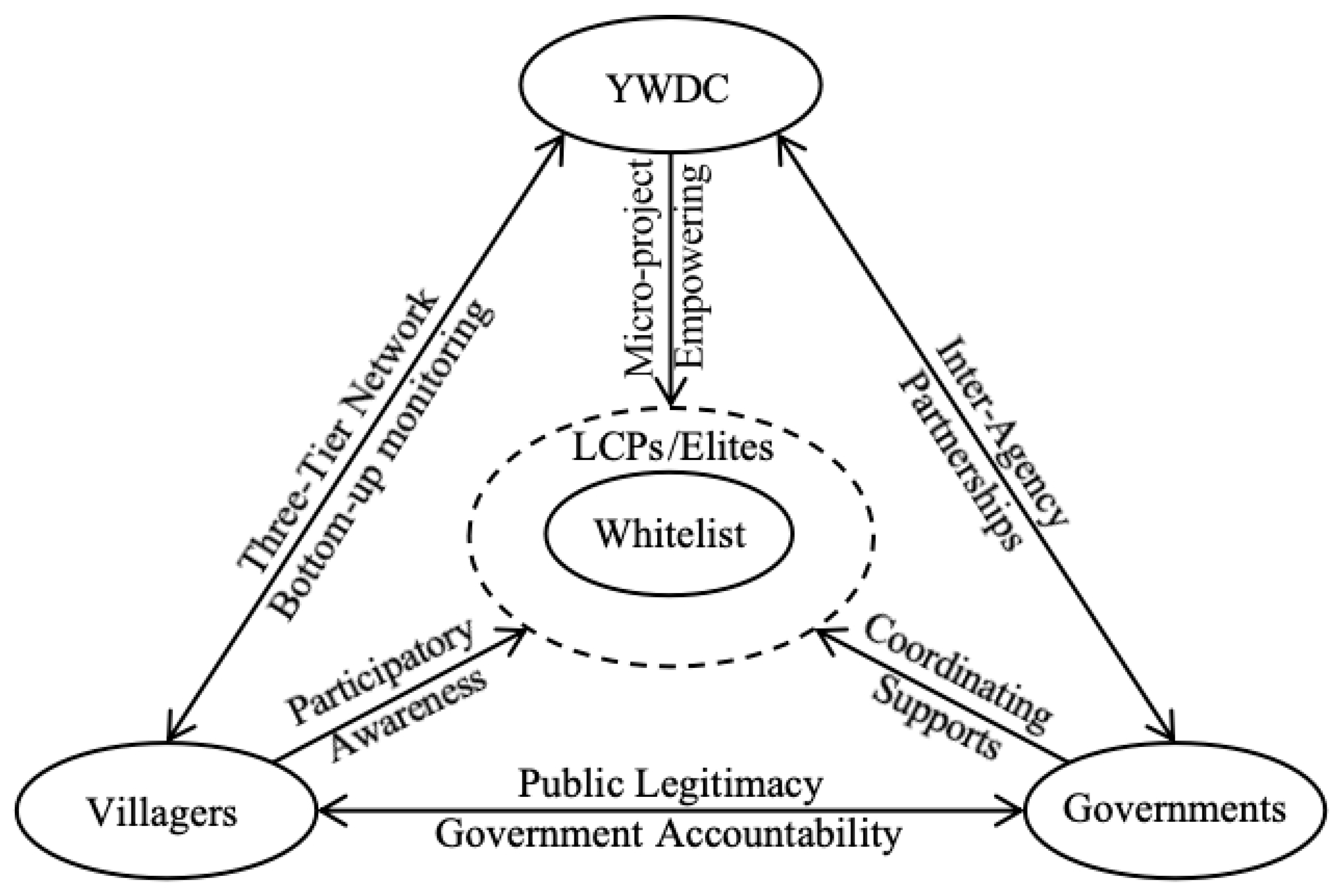

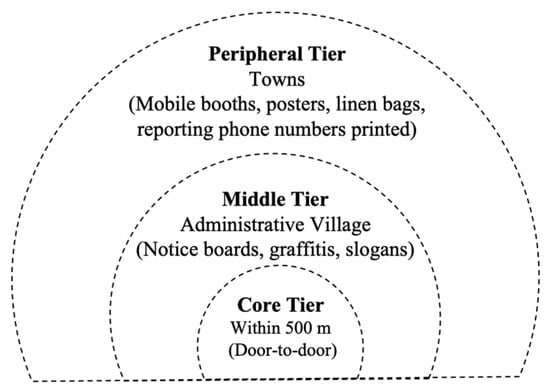

Figure 4 shows the whitelist at the core of a tripartite pyramid, with the co-monitoring interface composed of governments, SWDA, and villagers. Together, they exert influence on the elites through micro-project empowerment, participatory awareness, and coordinating support. The triangular partners consolidate their positions through mutual communications.

Figure 4.

Tripartite spiral to curb elite capture in “moderate supervision”. Source: drawn by the authors.

According to our internal statistics, after using the whitelist, the rework and modification rate of micro-projects has decreased from 17.3% to 4.1%. Public satisfaction scores have risen from 68 to 91, and petition complaints have dropped by 82%. The new method has indeed proven effective.—Interviewee No. 24091301, Director Wang, SWDA Office

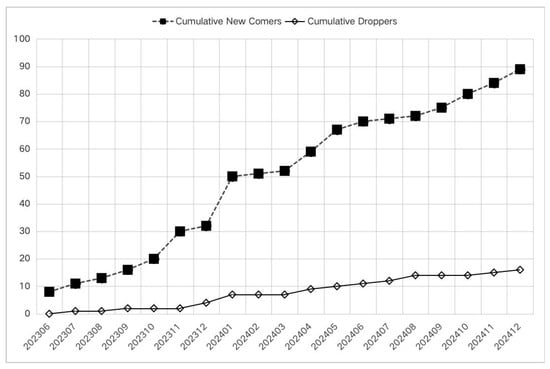

For the LCPs, although the competition pushes them out of their former comfort zones, with some even being eliminated from the game, the most capable can survive both the tripartite co-monitoring and their peers. An interesting phenomenon was that since the release of the “Notice Regulating ‘micro-projects’”, the number of newly registered LCPs increased from 8 at the very beginning to 89 by the end of 2024, while the cumulative droppers were less than 20 [82]. The LCP team is growing instead of shrinking (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of cumulative newcomers and droppers since 2023 [82].

These results demonstrate that the mutual monitoring element has effectively shifted focus from basic compliance to quality, reduced bureaucratic transaction costs, and aligned project outputs with community needs.

Through the “moderate supervision” mechanism, the mindsets and relations among governments, LCPs, or the elites, villagers, and SWDA have been remolded. Formerly, securing the project application’s success was often determined by whether the LCP had stronger personal connections than others. However, under the “moderate supervision” mechanism, the deciding factors are enlarged to 20 indicators, covering whether the LCP is qualified in economic, cultural, and social capitals, with a newly structured relational network emphasizing integrity, credibility, morality, professional capacity, and managerial proficiency, among others. It sets a new mold with the four agents in a brand-new “dedication” social structure, instead of a “capture” one, to evaluate each player in the new arena with new game rules.

5. Discussion

Globally, principles of moderate supervision resonate with adaptive governance, which emphasizes flexible, iterative decision-making tailored to local conditions rather than rigid, top-down regulation [83]. This is particularly relevant in rural contexts with highly dynamic social, economic, and ecological systems. A key feature of “moderate supervision” is its integrated assessment of economic, cultural, and social capital, which recognizes the multifaceted contributions of LCPs and enhances the perceived fairness and effectiveness of the system. Moreover, a core objective of this innovation is to bolster social stability and regime legitimacy, as demonstrated by the sharp reduction in petition complaints—a priority within China’s governance framework [84]. Informal institutions fulfil four essential roles within the moderate supervision mechanism: Primarily, they serve to reduce the transactional expenses of monitoring. Informal standards of mutual obligation, standing, and societal influence encourage adherence without ongoing formal involvement. This is more likely to happen if a villager is concerned about social censure or the diminution of their status than if they are merely apprehensive of a remote, official sanction. Secondly, there is an enhancement of the legitimacy of formal rules. When formal state policies align with informal values such as fairness, collective responsibility, or respect for local leadership, it changes instructions from the top to shared ideas that everyone follows. The center of the “core–periphery” structure is more respected and emphasized. Thirdly, the sharing culture narrows the gap between the elite and the public. Policies, violations, and the status of communal resources are facilitated by the three-tier mobilization system, which relies on informal social networks, such as kin groups, village elders, and local gossip. Providing information to stakeholders ensures public oversight and mutual monitoring, as a key basis for mobilization for CPR governance. Finally, informal institutions can help adapt to local situations. The reform of water conservancy projects emphasizes localization, enabling the system to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. Local elites can understand and apply rules in ways seen as fair and relevant to the situation. Indigenous knowledge of rural residents provides practical solutions to challenges during the project implementation.

The “co-monitoring” system is made cohesive by informal institutions, which are the glue that holds it together. They also act as the lubricant that allows its components—government, elites, and villagers—to interact smoothly. This reduces friction and builds trust necessary for sustained cooperation [77]. However, critical reflection reveals several challenges that require attention. First, the potential for elite entrenchment persists. A formal whitelist could inadvertently create barriers to entry for new actors, solidifying the power of an incumbent group and defeating the purpose of broadening participation [12]. Second, without careful design, such initiatives can reinforce existing power hierarchies rather than disrupt them, silencing the voices of women, ethnic minorities, and the economically disadvantaged who lack the social capital to participate effectively [85]. Third, the administrative burden of maintaining a dynamic, transparent, and fair evaluation system is non-trivial and requires sustained resources and institutional commitment. The transaction costs of maintaining such a system—training evaluators, managing data, addressing disputes—are often under-accounted for in participatory models, which could undermine the system’s scalability and long-term viability [86].

As pointed out by Joshi and Moore, institutionalized co-production in the Global South does not have to be a formal institution. Unorthodox public service delivery is more effective in challenging environments, such as Pakistan’s public security sector or Ghana’s tax collection area [71]. Even so, the longevity and replicability of this approach are still contingent on addressing key contextual and operational factors to exploit institutional advantages and avoid its disadvantages.

6. Conclusions

From the discussion above, it could be concluded that the “moderate supervision” mechanism has avoided risks in LCPs’ potential elite capture. This mechanism is impressive because it provides a mini-prototype for a potential approach to deconstruct the “core–periphery” power relations and reshape the elite-centric hierarchy into an anti-monopolizing reconstruction, toward a co-evolutionary network.

Regarding transferability to other rural areas, the core principles of the approach are highly portable. The universal principles—incentivizing performance through reputational competition, hardwiring citizen feedback into official evaluation, and using multi-dimensional metrics—can be applied across diverse contexts to address common problems such as lack of accountability, misalignment between projects and community needs, and the dominance of local elites [69]. However, its long-term viability depends on institutionalizing robust safeguards against co-option. It requires ongoing resources for independent third-party audits to verify feedback authenticity, regular updates to evaluation criteria to prevent gaming, and formal channels for addressing grievances about the process. Without these protective mechanisms, the system risks succumbing to the very elite capture and community power dynamics it was designed to mitigate [87].

To scale up this mechanism is not just a matter of copying verbatim. It requires careful calibration to specifics. First is the social structures. The approach must be adapted to local power hierarchies, ethnic compositions, and gender dynamics to avoid reinforcing existing exclusions. In areas with more rigid social stratification, additional measures to amplify marginalized voices are essential [88]. Second is the political context. Moderate supervision’s effectiveness hinges on a minimum governmental commitment to act. In contexts without the political will to sanction underperforming elites or reward high performers, the system devolves into a meaningless exercise with eroded public trust [79].

7. Policy Recommendations

Addressing the challenges mentioned above is essential for reinforcing participatory configurations of the moderate supervision framework. For future directions, the regime’s resilience will depend on its capacity for local adaptation. Considering that rationale, a concise statement is given as the practical policy implications to underscore its real-world applicability.

7.1. More Operational Metrics for Optimized Pilot Competition

The evaluation approaches of whitelisting, mid-event supervision, and post-event auditing send out new signals that all stakeholders must behave themselves and even perform significantly beyond average expectations to win the micro-projects. The logic has been dramatically altered from the former strategy of meeting the minimum requirements. Entrepreneurship is needed to reach that higher level of relational construction. Based on an excellence-driven logic, a bonus scheme is seriously discussed based on the project evaluation results. Currently, there are three grades: “excellent”, “satisfactory”, and “in need of rectification”. Micro-project fund disbursement follows a “4-3-3” allocating method: the 1st allocation (40%) is paid upon completion in time, after which the auditing process follows. Suppose the project is evaluated as “in need of rectification”: rework must be delivered until it is “satisfactory”. Then, the 2nd allocation (30%) is paid. The 3rd allocation (30%) is paid if no quality problems are further reported after 1 year of completion. SWDA plans to set a bonus reserve fund for the projects with “excellent” results, awarding 5% of the total project budget to model the best practitioners. To institutionalize this approach, supplementing quantitative metrics with qualitative assessments and third-party audits is necessary to capture intangible outcomes and prevent degraded gaming [89].

7.2. Ways to Scale up Mutual Monitoring and Inter-Agency Coordination

The second condition might be a reasonable institutional design with selective incentives for networked mutual monitoring. By implementing term limits for whitelist status or mandatory review periods, the system could be further ensured to remain dynamic and open to new entrants and enhance independent and accessible avenues for the public to report manipulation or unfairness without fear of reprisal, thereby safeguarding the integrity of the feedback loop.

Different from the Murcia-Orihuela huertas in Spain, which use a small amount of fining as a blacklisting strategy, YWPC is using a new approach to provide selective incentives to the elites (groups) as a positive signal to be followed. To achieve the notion of Michael Foucault’s governmentality [90], costing less money for better effects, it demonstrates how the pro-private elites could be reshaped and nurtured by benign institutions toward pro-public elites. To achieve this goal, inclusive facilitation methods could be designed, such as separate informal forums for marginalized groups, to amplify their voices [91], with continued implementation of robust anonymization protocols, mobilizing and communicating with them clearly to build trust. More intelligent measures, such as digital empowerment, are required to guarantee the information security of reporters and enhance the reliability of supervision and reporting channels. Anonymous supervision avenues need to be developed, which could draw upon the experience of China’s 12345-complaint hotline, for which the reporters could decide whether to disclose their contact details [92]. Additionally, a public information release platform might help to enable personal participation, which encourages transparency, efficiency, and participation, reflecting the global trend of digital governance [93]. In a word, whitelist indicators, the three-tier mobilization network, and inter-agency coordination have the potential to remold “privately capturing” into “public dedication”. When the pro-public game rules are set correctly, all stakeholders can recognize that partnerships, government legitimacy, shared authoritative resources, bottom-up monitoring, and selective incentives are essential for achieving the most benefits in sustainable governance of the CPR of water.

Author Contributions

L.L. (Li Li): supervision, conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, funding acquisition; L.L. (Linli Li): formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation; Q.L.: field visits coordination, validation, data curation, visualization; A.A.S.: visualization; Q.L. and A.A.S.; supervision, A.A.S.; co-supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 23GJB00438).

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

While preparing this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4.0 to improve the language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Narayan, J. Large Dams and Sustainable Development: A Case-study of the Sardar Sarovar Project, India. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2001, 17, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Barnett, J.; Webber, M.; Finlayson, B.; Wang, M. Governmentality and the conduct of water: China’s South-North Water Transfer Project. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2016, 41, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, P. Life cycle assessment of water supply alternatives in water-receiving areas of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project in China. Water Res. 2016, 89, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Luo, Z.; Webber, M.; Rogers, S.; Rutherfurd, I.; Wang, M.; Finlayson, B.; Jiang, M.; Shi, C.; Zhang, W. Project and region: The challenges of managing water in Shandong after the South-North Water Transfer Project. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Forge Ahead with New Chapters: A Documentary Account of the 10-Year Development of Shandong Water Diversion Project Operation and Maintenance Center. Available online: https://sdqy.dzwww.com/jrtt/202210/t20221018_10951597.htm (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Shandong Development and Reform Commission (SDRC). Announcement on Soliciting Opinions on Water Supply Prices of Water Diversion Projects Price Division of SDRC. 10 March 2025. Available online: https://www.yantai.gov.cn/art/2024/9/12/art_65384_3015101.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- The State Council of China. Implementation Opinions for Restructuring on the Reform of the Management System of Water Conservancy Projects ([2002]45). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2002/content_61785.htm (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Yu, Z.; Xu, G.; Yu, G. The current situation and suggestions of rural collective property rights transactions: A case study of Chun’an county, Zhejiang Province. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. (Xiandai Nongye Keji) 2021, 10, 233–234+237. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Huang, Z. The Paradigm Shift, Intrinsic logic and future trend of rural infrastructure construction policies. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 1, 198–206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y. Research on the path of rural collective economic development for achieving rural industrial revitalization: A case study of village w in Yuexi county. China Collect. Econ. 2024, 21, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bardhan, P.; Mookherjee, D. Capture and governance at local and national levels. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platteau, J.-P.; Abraham, A. Participatory Development in the Presence of Endogenous Community Imperfections. J. Dev. Stud. 2002, 39, 104–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ostrom, V. Public Economy Organization and Service Deliverry, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Indiana University; The University of Michigan: Dearborn, MI, USA, 1977; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J.-P.; Gaspart, F. The risk of resource misappropriation in community-driven development. World Dev. 2003, 31, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, K. Elite capture, the “follow-up checks” policy, and the targeted poverty alleviation program: Evidence from rural western China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 880–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzen, S.A. Can the design of community-driven development reduce the risk of elite capture? Evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1359–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.F.; Saito-Jensen, M. Revisiting the issue of elite capture of participatory initiatives. World Dev. 2013, 46, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, N. Political structure as a legacy of indirect colonial rule: Bargaining between national governments and rural elites in Africa. J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 44, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persha, L.; Andersson, K. Elite capture risk and mitigation in decentralized forest governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 24, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, K. Legal experts colluding with the political and economic elites in justifying corruption: The case of Malaysia’s Madani government. Palgrave Commun. Palgrave Macmillan 2025, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Analysis on the type and mechanism of villages managed by the rich. Soc. Sci. Beijing (Beijing Shehui Kexue) 2016, 9, 4–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Tan, L. The governance of rural areas with intensive endogenous interests: A case study of Town H in the southeast. CASS J. Political Sci. 2015, 3, 67–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, D. Elite Capture and Corruption: Concepts and Definitions; Working Paer of National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER); NCAER: Delhi, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buhlmann, F.; Mach, A. Political and economic elites in Switzerland: Personal interchange, interactional relations and structural homology. Eur. Soc. 2012, 14, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lin, C. The evolutionary logic of differences in the effectiveness of rural governance with capable returnees--A longitudinal observation of tenure with capable returnees as village cadres in S Town. J. Nanchang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 55, 119–130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, H.; Hu, R. Local government behavior in rural construction land marketization in China: An archetype analysis. Land Use Policy 2024, 142, 107189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Z.; He, S. The phenomenon of elites in the process of self-organizing operations. Soc. Sci. China 2013, 10, 86–101+206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, A. Competition and circulation of economic elites: Theory and application to the case of Peru. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2008, 48, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. In Defense of Water: Modern Mining, Grassroots Movements, and Corporate Strategies in Peru. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2016, 21, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, D. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice; Pluto Press: London, UK; Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J.-P. Monitoring Elite Capture in Community-Driven Development. Dev. Change 2004, 35, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Yale University Press: Hew Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA; London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. The Non-political Politics of Climate Change. ACME Int. E-J. Crit. Geogr. 2013, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1965; Volume 8, pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Forms of Capital: General Sociology, Vol.3: Lectures at the Collège de France 1983–1984; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Wang, S. Does China’s targeted poverty registration face the challenge of elite capture? J. Manag. World 2017, 1, 89–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. China’s Practice in Poverty Alleviation for Humanity; Xinhua News Agency: Beijing, China, 6 April 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-04/06/content_5597952.htm (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J. Functional mechanism of elites driving the development of village collective economy in the context of rural revitalization. China Econ. 2024, 7, 140–142+146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 45, pp. 182–184. [Google Scholar]

- Maass, A.; Anderson, R.L. And the Desert Shall Rejoice: Conflict, Growth and Justice in Arid Environments; R.E. Krieger: Malabar, FL, USA, 1986; Volume 83, p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Siy, R.Y. Community Resource Management: Lessons from the Zanjera; University of the Philippines Press: Manila, Philippines, 1982; Volume 95, p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Keesing, F.M. The Ethnohistory of Northern Luzon; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yin, L.; Zeng, Y. How new rural elites facilitate community-based homestead system reform in rural China: A perspective of village transformation. Habitat Int. 2024, 149, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Analysis of existing problems with management of construction projects bidding and solutions to the problems. J. Archit. Res. Dev. 2021, 5, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabah, R.; Abdulraheem, F. Influence of the new tender law on construction project bid prices and durations in Kuwait. J. Eng. Res. 2021, 9, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palcic, D.; Reeves, E.; Flannery, D.; Geddes, R.R. Public-private partnership tendering periods: An international comparative analysis. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2019, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, J. The balance of unbalanced bidding. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 21, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Whang, S.W.; Donyavi, S.; Flanagan, R.; Kim, S. Balanced approach for tendering practice at the pre-contract stage: The UK practitioner’s perspective. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2022, 28, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, X.; Shao, D.; Zhong, H.; Liang, J. Evaluation of water quality in the South-to-North Water Diversion Project of China using the water quality index (WQI) method. Water Res. 2020, 178, 115781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Yearbook of Shandong Water Diversion Project 2019; Heilongjiang Education Publishing House: Harbin, China, 2020; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- National Geomatics Center of China (NGCC). Administrative Division Information (1:1,000,000) and SWDP-YS Project Documents (1:250,000). Available online: https://www.webmap.cn/store.do?method=store&storeId=2 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Shandong Yellow River Water Diversion Irrigation Area (SWDA). Notice Regulating ‘Micro-Projects’ of SWDP-SD; SWDA: Yantai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D. Polycentricity and Local Public Economies: Readings from The Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, D.M.; Milgrom, P.; Roberts, J.; Wilson, R. Rational Cooperation in the Finitely Repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma. J. Econ. Theory 1982, 27, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D.M.; Wilson, R. Reputation and Imperfect Information. J. Econ. Theory 1982, 27, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchuluun, A.; Pardalos, P.M.; Migdalas, A.; Pitsoulis, L. Pareto Optimality, Game Theory And Equilibria; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. The Individualization of Chinese Society; Routledge: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Richardson, J. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Heberer, T.; Senz, A. Streamlining Local Behaviour Through Communication, Incentives and Control: A Case Study of Local Environmental Policies in China. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2011, 40, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P. Decentralization of Governance and Development. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. A Public Management for All Seasons? Public Adm. 1991, 69, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shue, V.; Thornton, P.M. To Govern China: Evolving Practices of Power; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, L.L. Accountability Without Democracy: Solidary Groups and Public Goods Provision in Rural China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert, G.; Halligan, J. Managing Performance: International Comparisons; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Moore, M. Institutionalised Co-production: Unorthodox Public Service Delivery in Challenging Environments. J. Dev. Stud. 2004, 40, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? World Bank Policy Research Report; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say? World Dev. 2015, 72, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.; Wright, E.O. Deepening Democracy: Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance. Politics Soc. 2001, 29, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Beard, V.A. Community Driven Development, Collective Action and Elite Capture in Indonesia. Dev. Change 2007, 38, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, G.; Levitsky, S. Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda. Perspect. Politics 2004, 2, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- He, B. Deliberative citizenship and deliberative governance: A case study of one deliberative experimental in China. Citizsh. Stud. 2018, 22, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertha, A. China’s “Soft” Centralization: Shifting Tiao/Kuai Authority Relations. China Q. 2005, 184, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Section. “Statistics of cumulative newcomers and droppers since 2023 on the release of Notice Regulating ‘Micro-Projects’”. Financial Work Summary of SWDA. 23 December 2024.

- People’s Government of Yantai City. Measures for the Management of Water Diversion in Yantai City, Bulletin of Government Y, China, 6 June 2017. For the reason of anonymity, The official website link is not provided here. (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minzner, C. End of an Era: How China’s Authoritarian Revival is Undermining Its Rise; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A. Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, meanings and practices. Community Dev. J. 2008, 43, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Community-Based and -Driven Development: A Critical Review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2004, 19, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.J.; Li, L. Rightful Resistance in Rural China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, A.L.; Schubert, G. Effective policy implementation in China’s local state. Mod. China 2015, 41, 372–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, T. “The Birth of Bio-Politics”: Michel Foucault’s Lecture at the Collège de France on Neo-liberal Governmentality. Econ. Soc. 2001, 2, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Does women’s proportional strength affect their participation? Governing local forests in South Asia. World Dev. 2010, 38, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, Y.; Si, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. A social sensing approach for everyday urban problem-handling with the 12345-complaint hotline data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 94, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F.; Carter, L. Digitizing Government Interactions with Constituents: An Historical Review of E-Government Research in Information Systems. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 363–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).