1. Introduction

The Brazilian Amazon harbors one of the greatest biological diversities on the planet but still presents significant knowledge gaps regarding its fauna, especially freshwater fishes [

1]. These gaps arise both from a lack of specialists and research resources and from the limited appreciation of scientific collections as tools for teaching and popularizing knowledge [

1,

2]. Zoological collections play a strategic role by preserving reference biological material, enabling taxonomic, ecological, and historical analyses [

3]. However, their educational potential remains underexplored, with timid insertion in school curricula and community practices.

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), as defined by UNESCO, seeks to integrate principles, values, and practices oriented toward sustainability in all dimensions of education, encouraging changes in attitudes and behaviors [

4]. In science teaching, zoological collections offer unique opportunities for meaningful learning by allowing direct contact with real specimens, fostering the development of observation, classification, and data analysis skills, and facilitating the understanding of ecological and evolutionary processes [

5]. According to [

4], the key competencies for ESD include systems thinking, anticipatory, normative, strategic, collaborative, critical, self-awareness, and integrated problem solving. When applied to science teaching, such competencies contribute to forming citizens aware of environmental limits and committed to sustainable practices [

6]. Previous studies [

7,

8] show that integrating science and ESD into school curricula fosters socioemotional and critical skills development and stimulates reflection on the sustainable use of natural resources.

The UFOPA Ichthyological Collection, founded in 2012, houses about 650 species, including type material from different river basins, with emphasis on the Tapajós River—the second-largest clear-water tributary of the Amazon basin, with 982 valid fish species recorded [

2]. Maintained by the Laboratory of Ichthyology under the Institute of Water Sciences and Technologies, the collection serves teaching, research, and outreach functions. In the Amazonian context, the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection has emerged as a base for linking theory and practice. By gathering specimens of the Tapajós ichthyofauna, the collection provides the scientific inputs for producing educational resources—such as games, books, and guides—that translate technical data into accessible and culturally contextualized experiences. This strategy enables students, especially in riverside schools, not only to learn concepts of biology and ecology but also to develop ESD competencies by reflecting on the conservation of fishes that are part of their daily lives.

Despite its relevance for biodiversity research and conservation, zoological collections remain underused as pedagogical instruments, especially in the Amazon, where gaps in knowledge about ichthyofauna compound the scarcity of contextualized teaching resources. In the case of the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection, a gap is observed between the accumulated scientific collection and its use in basic and community education. This limitation raises a central question: how can the technical–scientific data of the Tapajós ichthyological collection be transformed into educational resources capable of contributing to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)?

The choice of an action research approach is justified by the direct involvement of researchers in transforming the ichthyological collection into educational resources. This participatory design aligns with the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), fostering collaboration among scientists, teachers, and students. Based on this problem, this study aims to translate the scientific collection of UFOPA’s Ichthyological Collection into accessible pedagogical materials, strengthening scientific literacy and bringing science, school, and community closer in the Tapajós region. Specifically, it seeks to: (i) systematize the taxonomic, ecological, and cultural data of the species recorded in the collection; (ii) identify criteria for selecting species with greater pedagogical potential; (iii) convert technical–scientific language into accessible formats through interdisciplinary collaboration; and (iv) produce diverse educational materials, such as a memory game, a coloring book, an illustrated guide, and an activity workbook. In this article, we describe in detail the methodological process of creation, while impact evaluation will be addressed in future studies.

UFOPA Ichthyological Collection profile. Established in 2012, the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection currently houses ~650 species, including type material from multiple Amazonian drainages, with an emphasis on the Tapajós River basin, where ~982 valid fish species have been recorded. Beyond its research role, the collection retains ecological and cultural value by documenting species central to local fisheries, food systems and community identity. Its curated metadata (taxonomic, morphological, ecological, geographic) enable reliable species recognition and contextual links (e.g., conservation status, cultural relevance), which are essential for producing accurate, age-appropriate educational materials that align science education with ESD principles.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological process was organized in four main stages: (i) systematization of scientific and sociocultural data from the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection, (ii) consultation with ichthyologists to identify species with pedagogical potential, (iii) public consultation with students, teachers, and civil society members, and (iv) development of educational materials. The study adopted a qualitative [

9], descriptive–exploratory approach based on action research, chosen for its capacity to integrate scientific production and educational practice. This approach assumes that research should be oriented toward solving practical problems and promoting active participation by those involved. In this study, the identified challenge was the gap between the scientific collection and basic education in the Tapajós region.

2.1. Study Area and Context

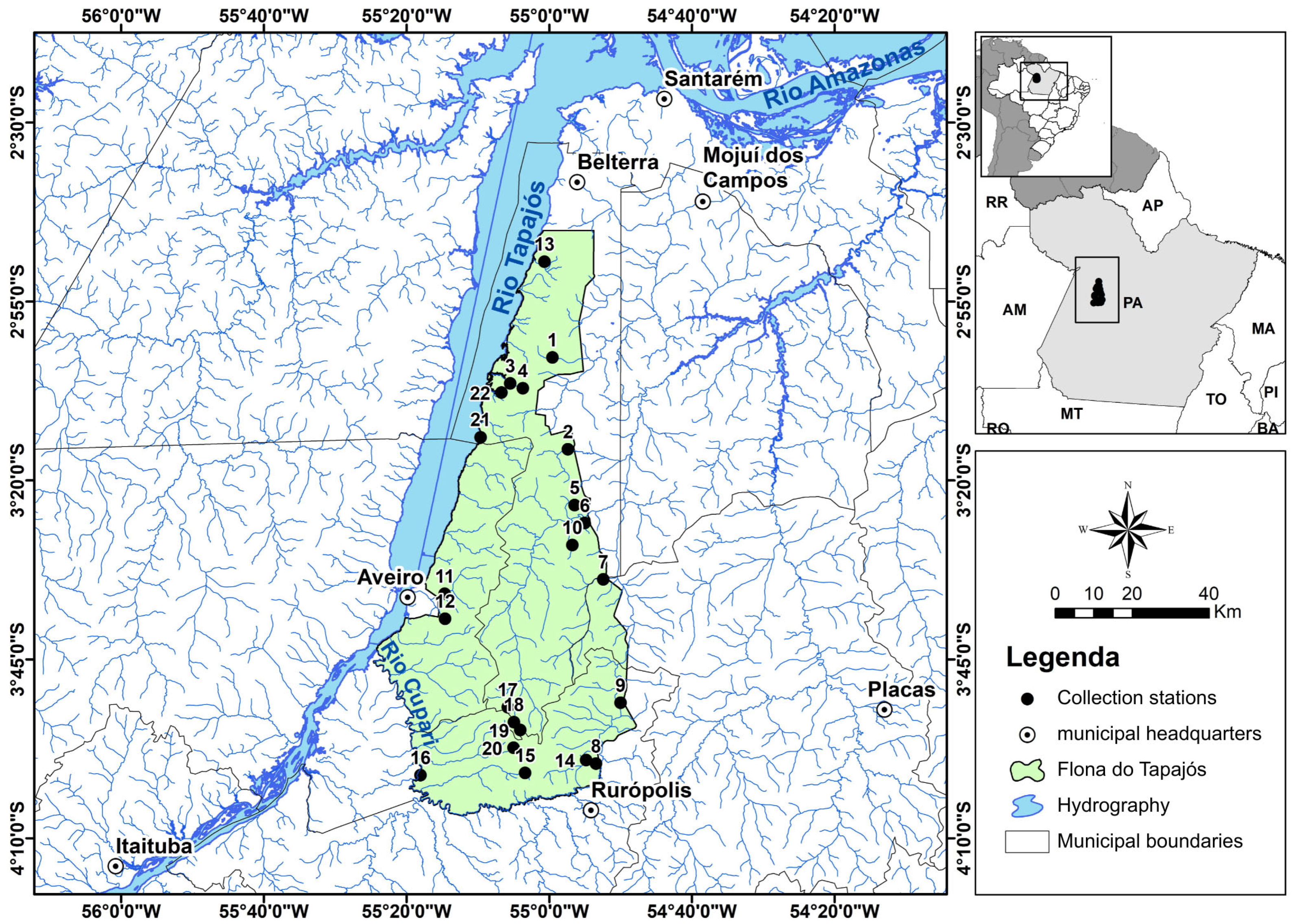

Most of the specimens in the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection originate from the Tapajós River basin (

Figure 1), particularly from drainages located at the confluence of the Tapajós National Forest and the Arapiuns, Cupari, and Tapajós Rivers, within the municipalities of Aveiro, Belterra, Itaituba, Rurópolis, and Santarém, Pará, Brazil.

2.2. Data Collection from the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection

A detailed review and systematization of taxonomic, ecological, and sociocultural data were conducted using specimens from the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection. A total of 100 specimens were analyzed, organized into an analytical matrix containing species name, family, habitat type, conservation status (IUCN), ecological role, and known cultural or economic uses among riverine communities. Seven interviews were conducted with ichthyologists affiliated with the UFOPA Ichthyology Laboratory between July and August 2024. The sample included five male and two female participants, aged 21–50 years, representing diverse educational backgrounds: bachelor’s in Biological Sciences, master’s in Biodiversity, and PhDs in Freshwater Biology, Systematics, and Taxonomy. The interviews were guided by 20 semi-structured questions distributed across six thematic axes: (i) relationship with the laboratory and research projects; (ii) perception of the collection’s scientific and educational relevance; (iii) communication and visibility; (iv) collaboration networks; (v) improvement perspectives; and (vi) educational and participatory potential.

2.3. Criteria for Species Selection

The interviews supported the identification of species most suitable for educational purposes, based on four guiding criteria: (i) visual recognizability, (ii) ecological importance, (iii) cultural significance, and (iv) frequency of occurrence in the Tapajós basin. This process combined expert judgment, reference literature, and collection data to prioritize 40 species with the highest pedagogical potential.

2.4. Public Consultation and Participatory Evaluation

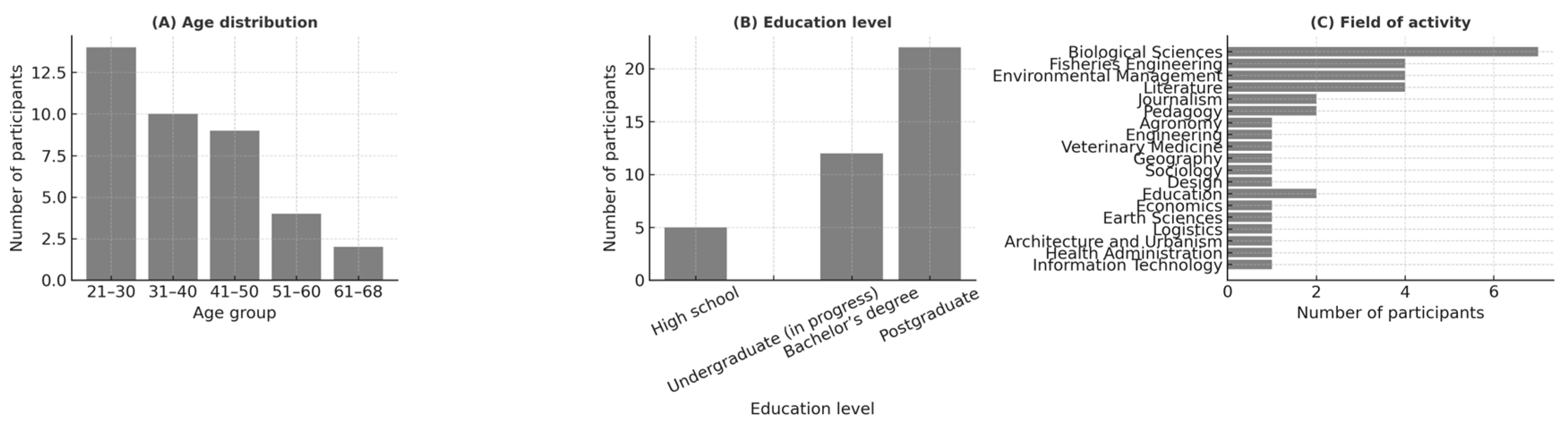

An online public consultation was conducted to expand participation beyond the academic community, engaging 39 respondents—students, teachers, and civil society members (

Figure 2). Participants contributed perceptions about which species, ecological information, and cultural aspects should appear in educational materials. The sample included five individuals with secondary education, 12 with higher education, and 22 with postgraduate degrees. Fields of activity were diverse, including Biological Sciences (7), Fisheries Engineering (4), Environmental Management (4), Literature (4), Journalism (2), and Pedagogy (2). Respondents prioritized content related to conservation status, cultural uses, and species recognition.

2.5. Development of Educational Materials

The educational materials were developed through interdisciplinary collaboration among ichthyologists, educators, and designers. The process integrated scientific rigor with pedagogical accessibility, translating complex taxonomic data into engaging educational content. Four materials were produced: (1) Illustrated Guide of Tapajós Fish (50 species with images and ecological data); (2) Coloring Book “Peixes do Tapajós”; (3) Memory Card Game; and (4) Multi-Grade Workbook. The workflow included selection of representative species, creation of vector illustrations from specimen photographs, simplification of technical language, pedagogical review, and layout design for local printing and distribution.

2.6. Ethical Procedures

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Western Pará (CAAE 78761124.8.0000.0171; Opinion No. 6.863.055, 3 June 2024). All participants signed informed consent forms prior to interviews or survey participation. Responses were anonymized, coded (PE1–PE7), and analyzed following confidentiality and data protection standards.

3. Results: Development and Characteristics of the Educational Products

The main outcome of this study was the elaboration of four pedagogical resources derived from the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection (see

Appendix A). These resources represent the practical synthesis of the methodological process described above. The subsequent implementation and educational assessment of these products will be reported in a future publication.

The systematization of data and the public consultation resulted in the creation of four main products: an illustrated species guide, a coloring book, a memory game, and a school activity workbook. These materials were designed to integrate scientific content with contextualized pedagogical practices, responding to technical criteria and interests identified in the public consultation, which gathered 39 participants and indicated the main interests of the potential audience for the information.

Among the most highlighted points were: the need for visual and accessible materials, the appreciation of content related to environmental conservation, and the preference for resources that dialog with local culture. Interviews with seven laboratory researchers, in turn, reinforced technical criteria such as taxonomic representativeness, ease of species recognition, and relevance for science teaching. The triangulation of these data sources made it possible to define priorities and guide the creation of the products.

The

Table 1 below summarizes this analysis, relating the criteria identified in the interviews and the public consultation with the developed products and the key competencies of Education for Sustainable Development [

4,

6].

Since November 2024, fish species records began to be organized and systematized to feed a database aimed at supporting the availability of the ichthyological collection in the mentioned products. The spreadsheet incorporates species information, identifying in key columns the following filters: “Common Name,” “Scientific Name,” “Collection Methodology,” “Adult Size,” “Geographical Distribution,” taxonomy, morphology, and biological details (feeding type, spawning period, behavioral habits); Morphological characteristics (shape, adult size, physical structure [scales, fins, color]); Taxonomic classification (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus).

The treatment of the material occurred in the following phases: organization of responses, category analysis, systematization, and selection of expressive fragments. This procedure was inspired by the content analysis method proposed by [

10], which involves message coding steps, identifying and categorizing important terms for the study scope, as well as interpretation to analyze their meanings.

The systematization of the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection identified 100 species, of which 40 were prioritized for pedagogical use according to technical and cultural criteria (endemism, visual recognition, local importance, and conservation). Complete taxonomic and morphological information for each species is available in

Appendix B (

Table A2).

Regarding geographical distribution, the analysis focused on species concentrated in the Tapajós River and its tributaries. Some species were cataloged exclusively in the Tapajós drainage, indicating potential endemism. The revised list of species cataloged in the UFOPA Ichthyology Laboratory highlights the rich diversity of fishes in the Tapajós region, showcasing both widely recognized species and those with uncertain taxonomic identification. The most frequent collections occurred in Santarém, Pará, in the following environments: lakes—Lago Verde, in the village of Alter do Chão; Itapari; Point 01 and Point 04 of Lago Juá; Sonrisal, UDV, and São Braz streams; Pindobal Beach; Arapiuns River. In the municipality of Rurópolis, Pará: Stream 08 and Stream 20. In the municipality of Belterra, Pará: Streams 03 and Branco.

Playing with Fish: Support Products for Education for Sustainable Development

Based on the survey of capacities, the process of elaborating the products began with a matrix containing systematized information on each species, considering the filters previously indicated in the public survey. In the next stage, this information was transcribed in an accessible and playful way to make it understandable to young audiences. Based on this matrix and the adaptation of information, four products were developed, ensuring that the content was didactic, attractive, and suitable for the age groups involved.

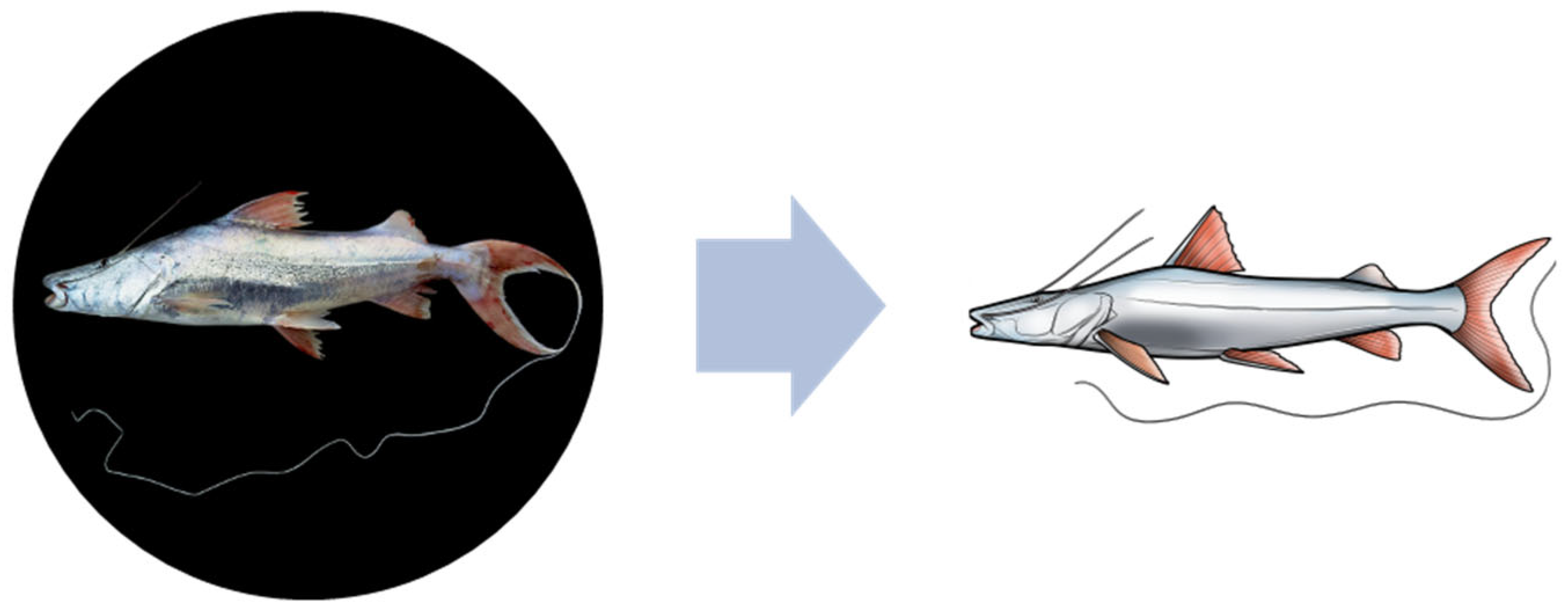

Using reference photos of the laboratory’s fish (

Figure 3), vector illustrations were created, which were used in the graphic designs. Real records were essential to ensure that each species was faithfully represented, respecting their anatomical particularities and regional characteristics. The use of visual references guaranteed a representation process that dignifies each species, valuing its specificities and enabling an accurate and visually coherent result for the graphic products.

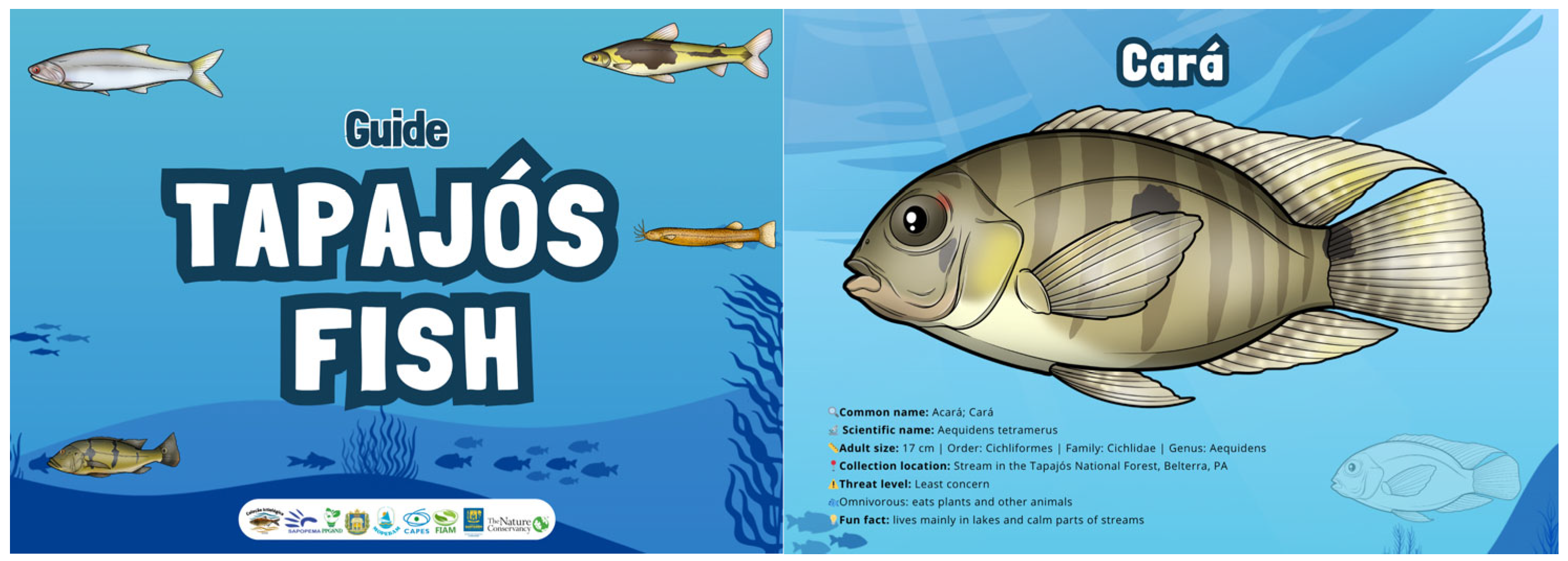

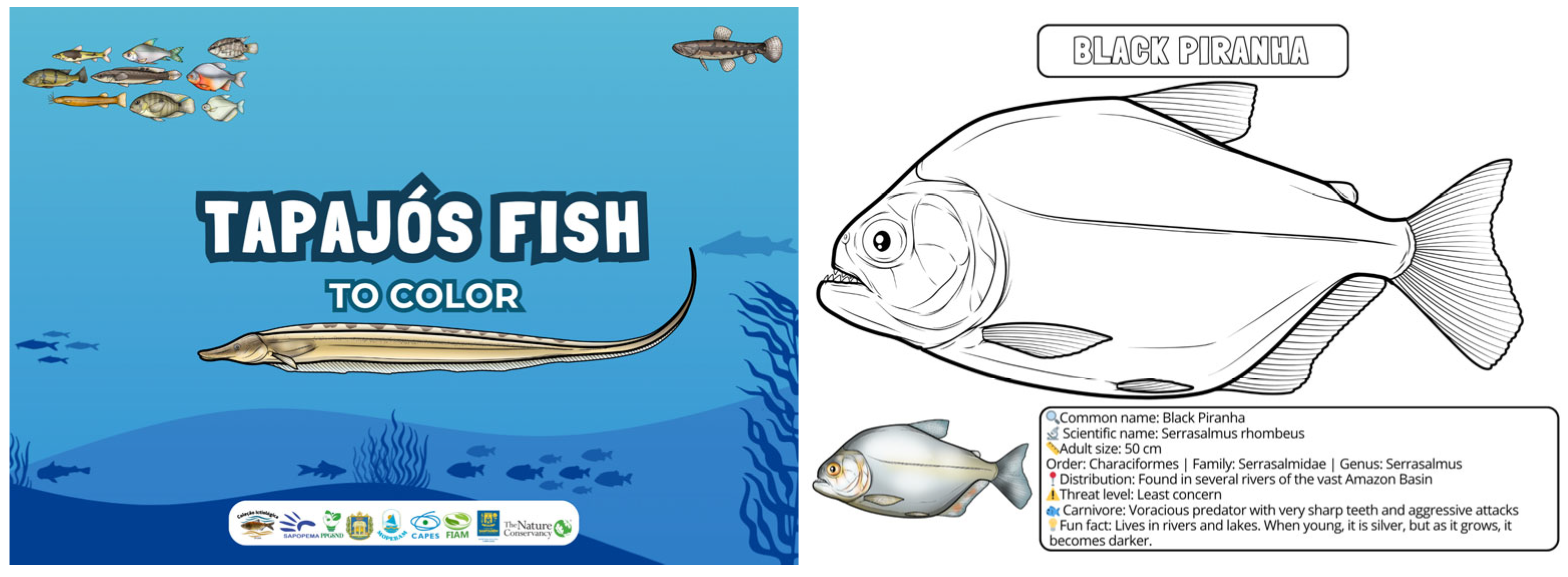

From the illustrations, the process of choosing formats and elaborating each piece of the products began. The first developed was the species guide (

Figure 4), which serves as the basis for the elaboration of the other materials. This guide is a fundamental resource for initial work with riverside schools, supporting environmental education activities and providing consistent support for student training and awareness about local biodiversity.

With the creation of linearts—vector versions of species without coloration—the coloring book was developed (

Figure 5). This material aims to bring children from the initial grades closer to local biodiversity, stimulating and sharpening children’s creativity. In addition to the illustrations, the book also includes information about each species, allowing learning to be playful and informative at the same time.

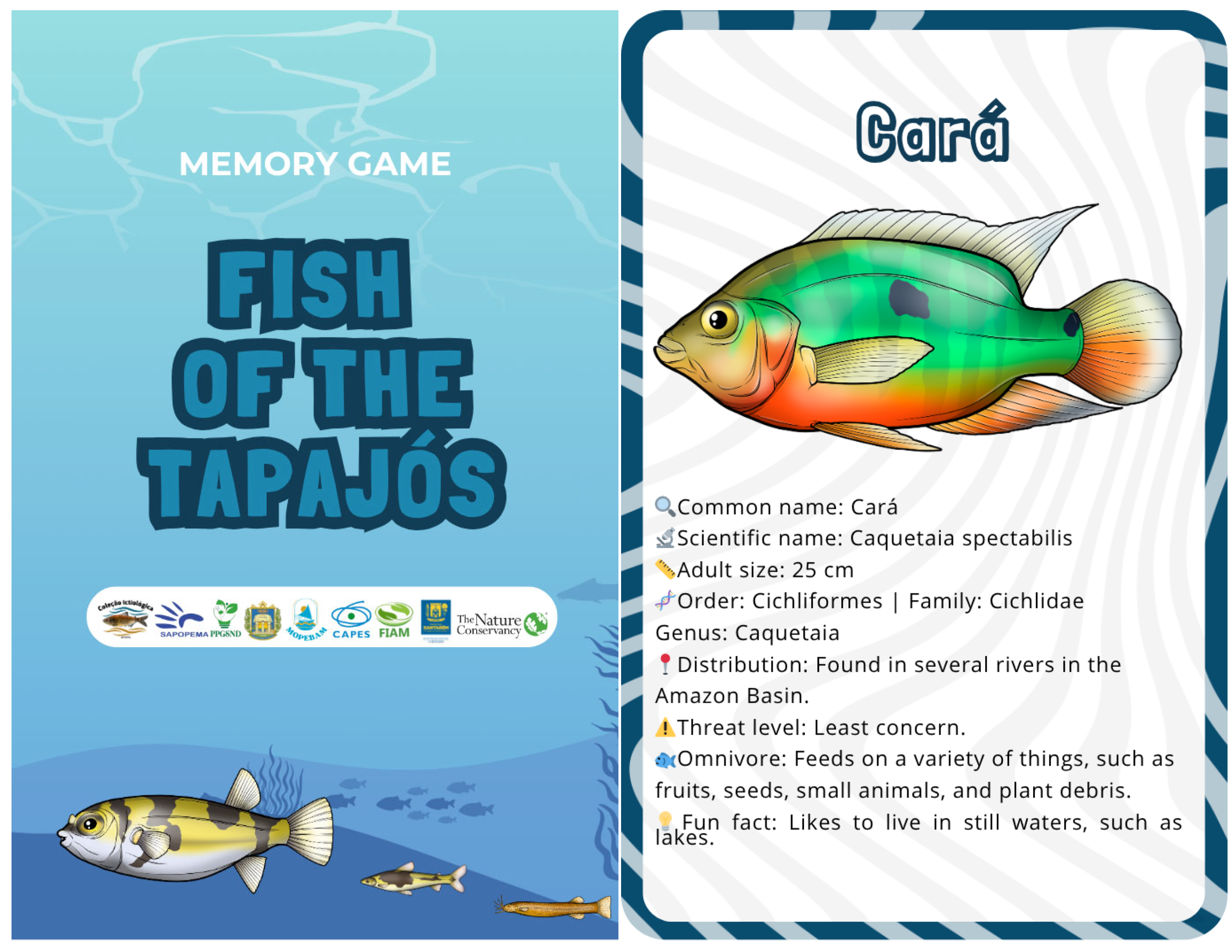

To promote spaces for exchange and interactivity in the school environment, a memory game (

Figure 6) was developed in a deck format, using the fish illustrations as cards, also accompanied by information about each species. The games were printed in this specific format to facilitate their application in classrooms, adopting a pedagogical strategy to integrate them into the activities of grades 1 to 9, stimulating playful learning and student interest in local biodiversity.

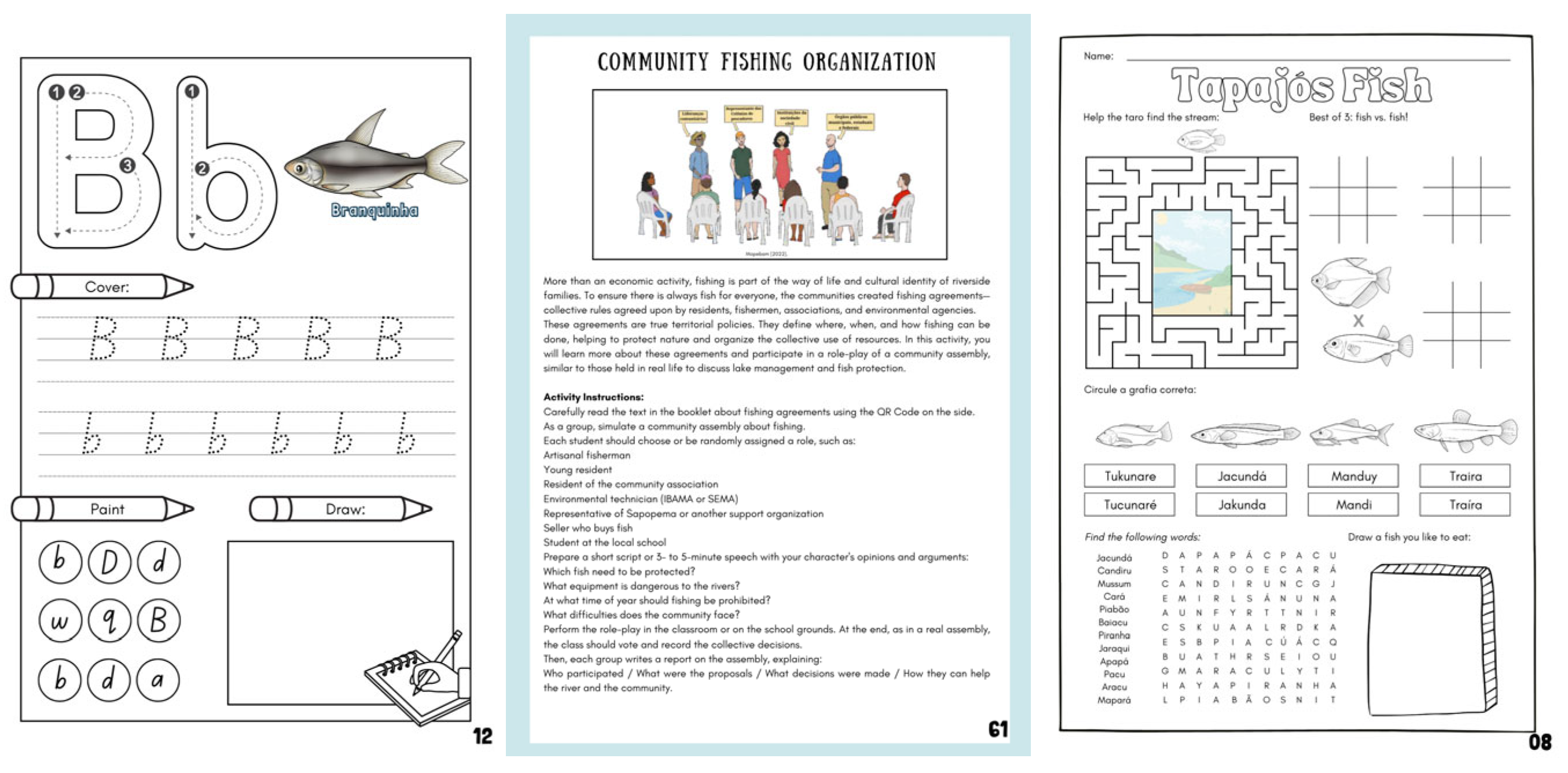

Finally, an activity workbook was developed as part of an initiative to popularize knowledge about the fishes of the Tapajós region, valuing the knowledge and ways of life of Amazonian riverside populations. Directed especially at the school public of riverside communities, the material integrates the teaching of language, mathematics, science, history, and geography, using content related to the territory, fishing, and care of the rivers.

The booklet was prepared in accessible language, with illustrated activities and a focus on the daily experiences of the region’s children and youth. It includes literacy exercises, correct spelling of fish names, alphabet activities, verbs and word searches; math problems contextualized with fishing—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, percentages, price calculation, and fractions; as well as reading informative texts and creative proposals that stimulate ties with the territory and community memory.

The workbook (

Figure 7) also addresses fundamental themes of riverside life and community management, such as fishing agreements, sustainable pirarucu management, the role of fishermen’s organizations, and the impact of floods and droughts in the region. The activities also cover history and geography content, such as fishing timelines, territorial transformations, and symbolic representation of the riverside life map, as well as expression and creative activities with dramatizations, “fish talks,” poster and video production. In the dimension of citizenship and community organization, the workbook promotes simulations of assemblies, studies on forms of fishery organization, and participation in decisions on the sustainable use of rivers.

The production of educational materials advanced significantly, but its implementation faces challenges, such as the high cost of printing, logistical limitations in riverside schools, and the need to sensitize teachers and managers to curriculum integration, reflecting challenges widely discussed in ESD [

4,

11].

At the same time, the results highlight promising opportunities. School community engagement strengthens local ties and broadens the sense of belonging, favoring meaningful learning. The articulation with the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals reinforces the political and social relevance of the project, aligning with the core domains and competencies of ESD, which integrate knowledge, skills, and values for sustainability [

4,

6].

Future steps include institutional partnerships to expand the printing and dissemination of materials, as well as studies to assess the impact on community engagement and school performance, consolidating the project as a replicable model in other socio-environmental contexts [

6,

12].

4. Discussion

This study highlights the potential of natural history collections as pedagogical resources for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). By transforming UFOPA’s Ichthyological Collection into educational materials, we demonstrate that scientific data can be translated into accessible formats that foster scientific literacy and community engagement.

The development of the educational materials based on the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection revealed how scientific data can be translated into pedagogical resources aligned with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

During the species selection process, this prioritization exercise, evaluative by nature, required applying the normative competence of ESD, as it involved defining values and ethical judgments about which species best represented the relationship between biodiversity and sustainability. This moment demonstrated that choosing which species to highlight in educational materials is not a neutral act, but an ethical decision reflecting cultural and ecological values of the Tapajós region.

In the subsequent stages, each resource was structured to integrate scientific content with contextualized pedagogical practices, in order to bring students closer to local biodiversity and foster science education guided by the principles of Education for Sustainable Development. This process revealed the potential of action research to bridge scientific and community knowledge through co-creation between researchers, educators, and local actors.

This stage especially mobilized strategic competence and integrated problem solving, as it required articulating scientific, pedagogical, and cultural dimensions in designing products that were simultaneously informative, engaging, and socially relevant. The collaborative workflow encouraged multidisciplinary communication and a problem-solving attitude consistent with ESD’s strategic and anticipatory competencies.

This step ensured that the products not only translated scientific data into accessible language but also directly engaged with social demands, reinforcing ESD’s commitment to promoting socially situated learning with potential for practical application in community life. These results highlight how participatory methodologies make educational materials more responsive to local contexts and meaningful for riverside schools.

Finally, this methodology brings science teaching closer to students’ reality, reinforcing cognitive competencies (observation, data analysis), socioemotional competencies (cultural appreciation, collaboration), and behavioral competencies (action for conservation). In this way, the UFOPA Ichthyological Collection becomes a space of mediation between science, school, and community, aligned with the perspective of Education for Sustainable Development and the 2030 Agenda. This synthesis confirms that scientific collections, when integrated into educational design, strengthen multiple ESD competencies simultaneously—cognitive, socioemotional, and behavioral—creating bridges between academic science and community practice.

Our findings converge with previous research showing that natural history collections can support formal and informal science education [

3,

5]. The four products created—memory game, coloring book, illustrated guide, and activity workbook—address key ESD competencies, such as systems thinking and normative and anticipatory skills [

4,

6], while responding to local cultural values identified in the public consultation.

However, the implementation process faces challenges similar to those reported by other initiatives integrating ESD and biodiversity education in remote areas [

12]: limited financial resources, logistical barriers to distributing materials in riverside schools, and the need for teacher training may restrict long-term impact. Addressing these challenges requires partnerships with local governments and NGOs to ensure continuity, teacher engagement, and curriculum integration.

Despite these limitations, the methodology adopted offers a replicable framework for other contexts and biomes. It demonstrates that combining participatory methods, interdisciplinary collaboration, and contextualized content can transform scientific collections into powerful tools for sustainability education, aligned with the 2030 Agenda, particularly SDGs 4 (Quality Education), 14 (Life Below Water), and 15 (Life on Land).

We discuss implementation challenges typical of ESD initiatives in remote settings (printing costs, distribution, teacher training) and outline partnerships with municipal education offices to support curriculum integration and scaling.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that scientific collections, traditionally aimed at research and conservation, can be reconverted into educational resources capable of strengthening Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). The experience of UFOPA’s Ichthyological Collection demonstrates that the systematization of biological data and its translation into accessible pedagogical materials expands scientific literacy and stimulates key ESD competencies such as critical thinking, collaboration, and problem solving.

By integrating science, education, and community participation, the process brings students and teachers closer to Amazonian biodiversity, fostering reflections on conservation and the sustainable use of aquatic resources. This approach also reveals replication potential in other contexts and biomes, pointing ways for zoological collections in Brazil and worldwide to become active instruments of the 2030 Agenda, especially in achieving Sustainable Development Goals 4 (Quality Education), 14 (Life Below Water), and 15 (Life on Land).

Scientific collections are configured as spaces of mediation between academic knowledge and social action, contributing to the formation of citizens aware and engaged in building sustainable societies. However, challenges remain related to the sustainability of material production and distribution, especially given the high printing costs and the constant need to attract supporters to make this front viable. In addition, there are limitations related to inserting the resources into school curricula and the institutional strengthening needed to expand the pedagogical use of these collections. Reflecting on these limits is essential to consolidate the replicability of the experience in other biomes and to encourage public policies that support similar initiatives. As future steps, partnerships are already being articulated with the Municipal Secretariats of Education of Santarém and Belterra, aiming at implementing the materials in riverside schools in a process that combines science popularization with regionalization of teaching.