A Three-Stage Process for Sustainable Telework Adoption

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Telework

1.1.2. Place of Work

1.1.3. Types of TW

1.1.4. Applicable Theories

1.1.5. Previous Research

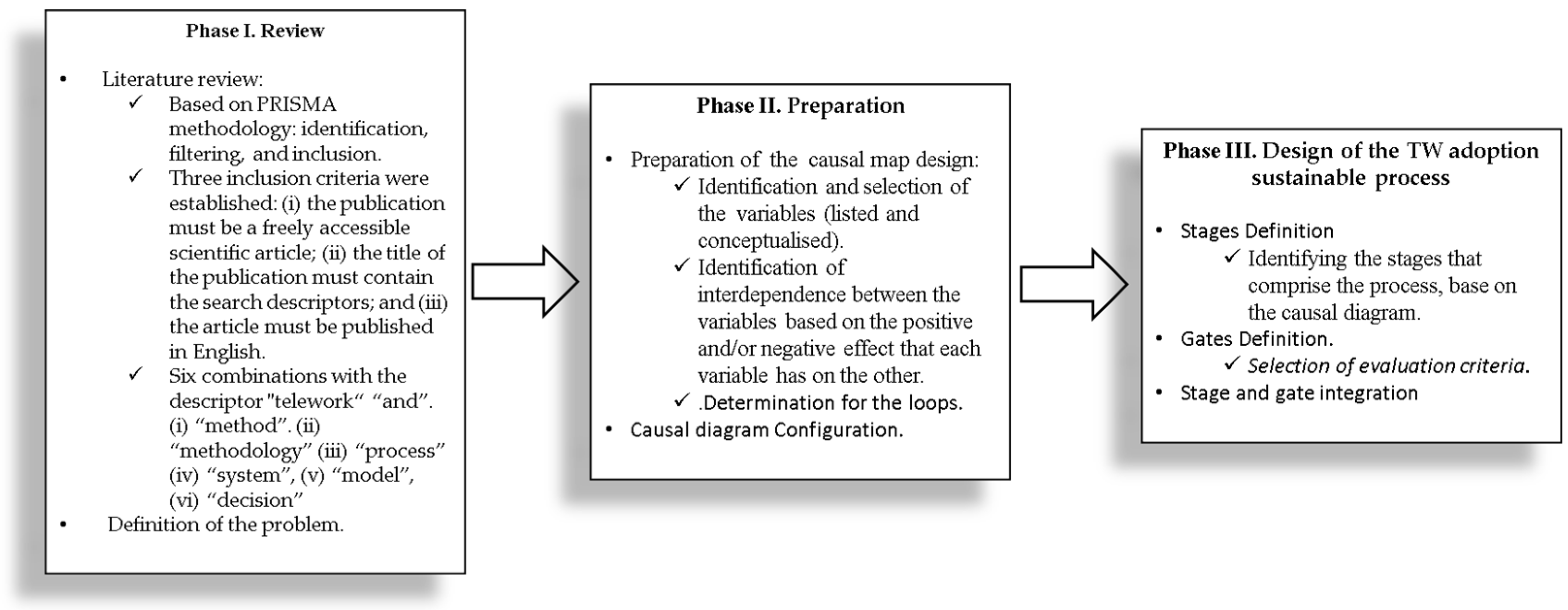

2. Materials and Methods

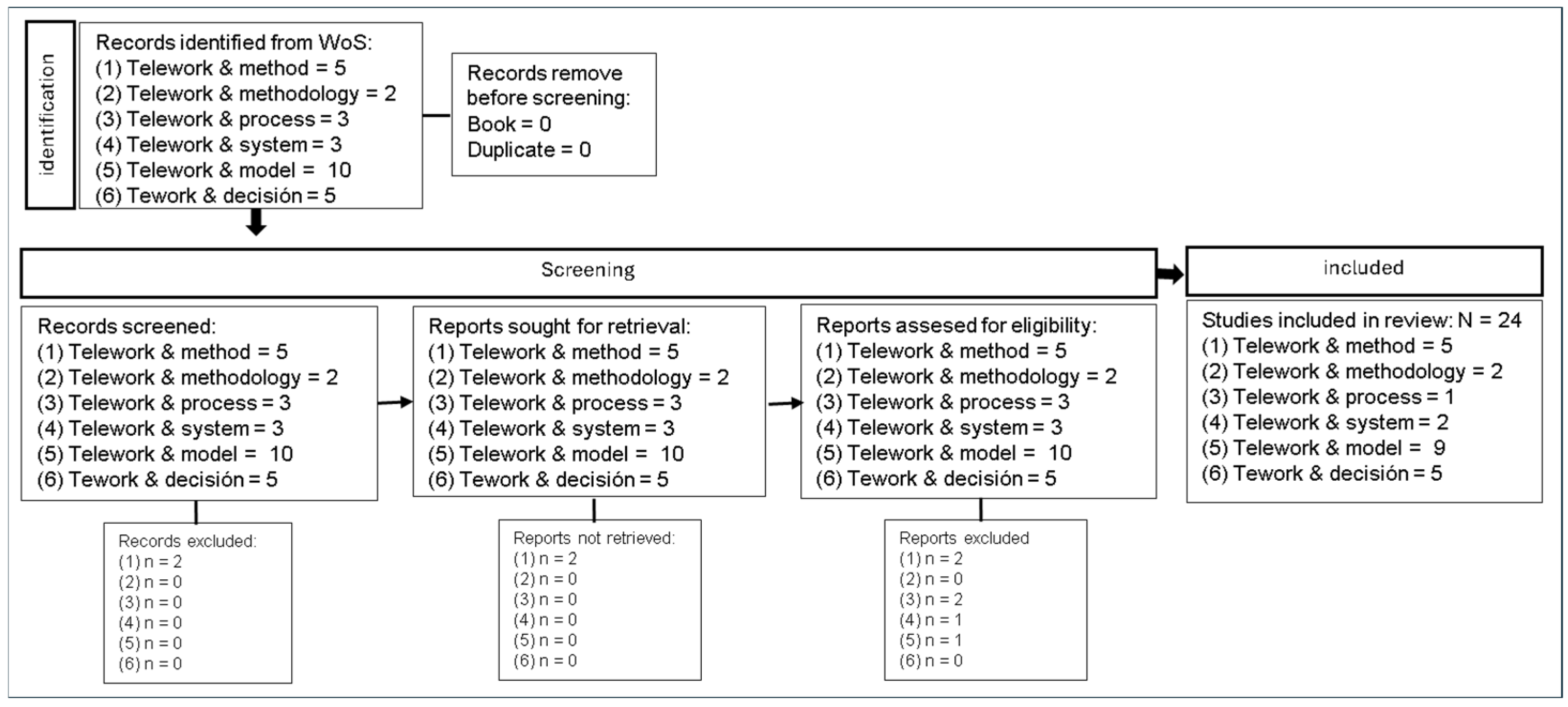

2.1. Phase I. Review

2.2. Phase II. Preparation

2.3. Phase III. Design of TW Adoption Sustainable Process

3. Results

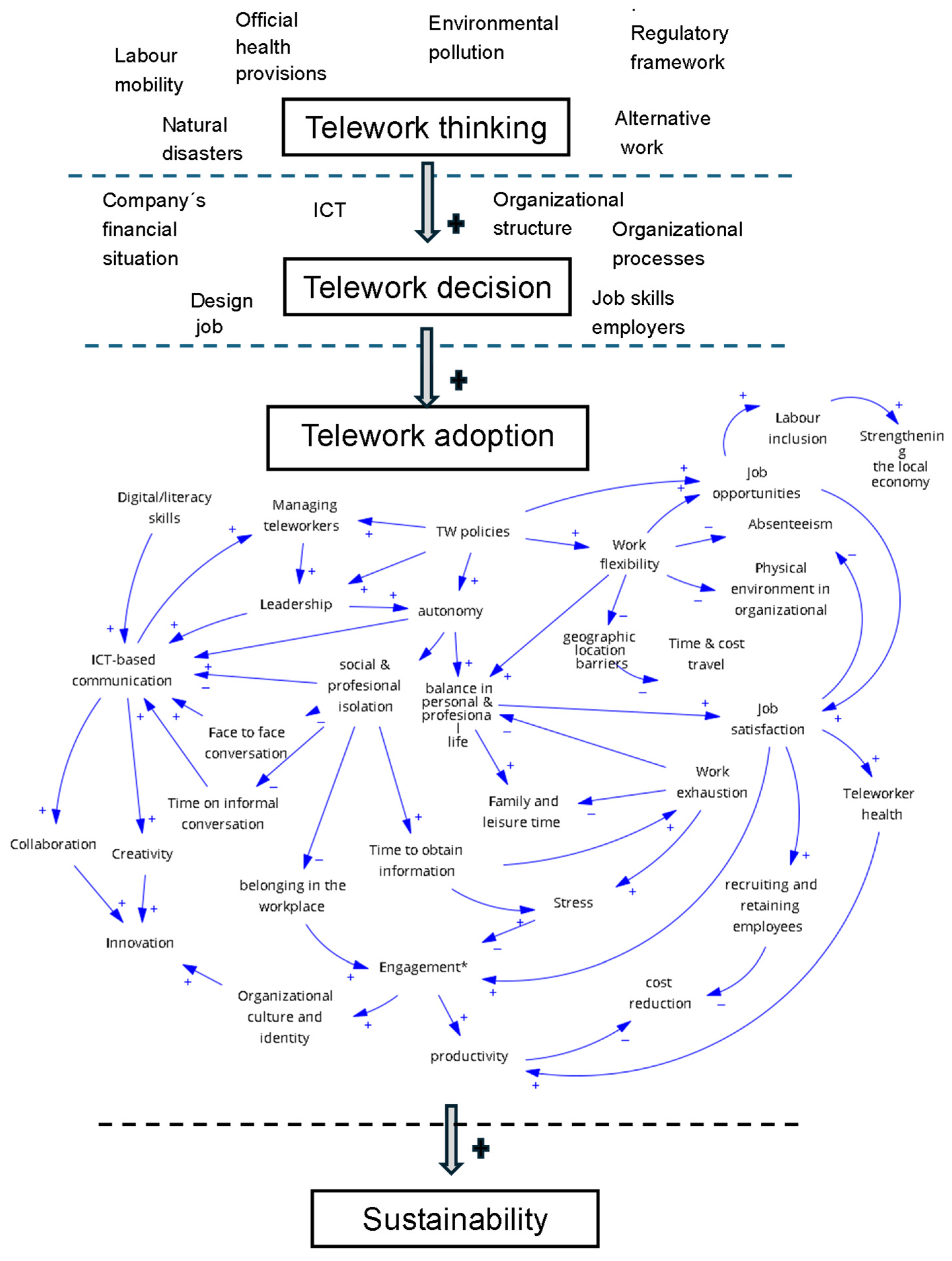

3.1. Causal Loop Diagram of TW Adoption Sustainable Process in the Company

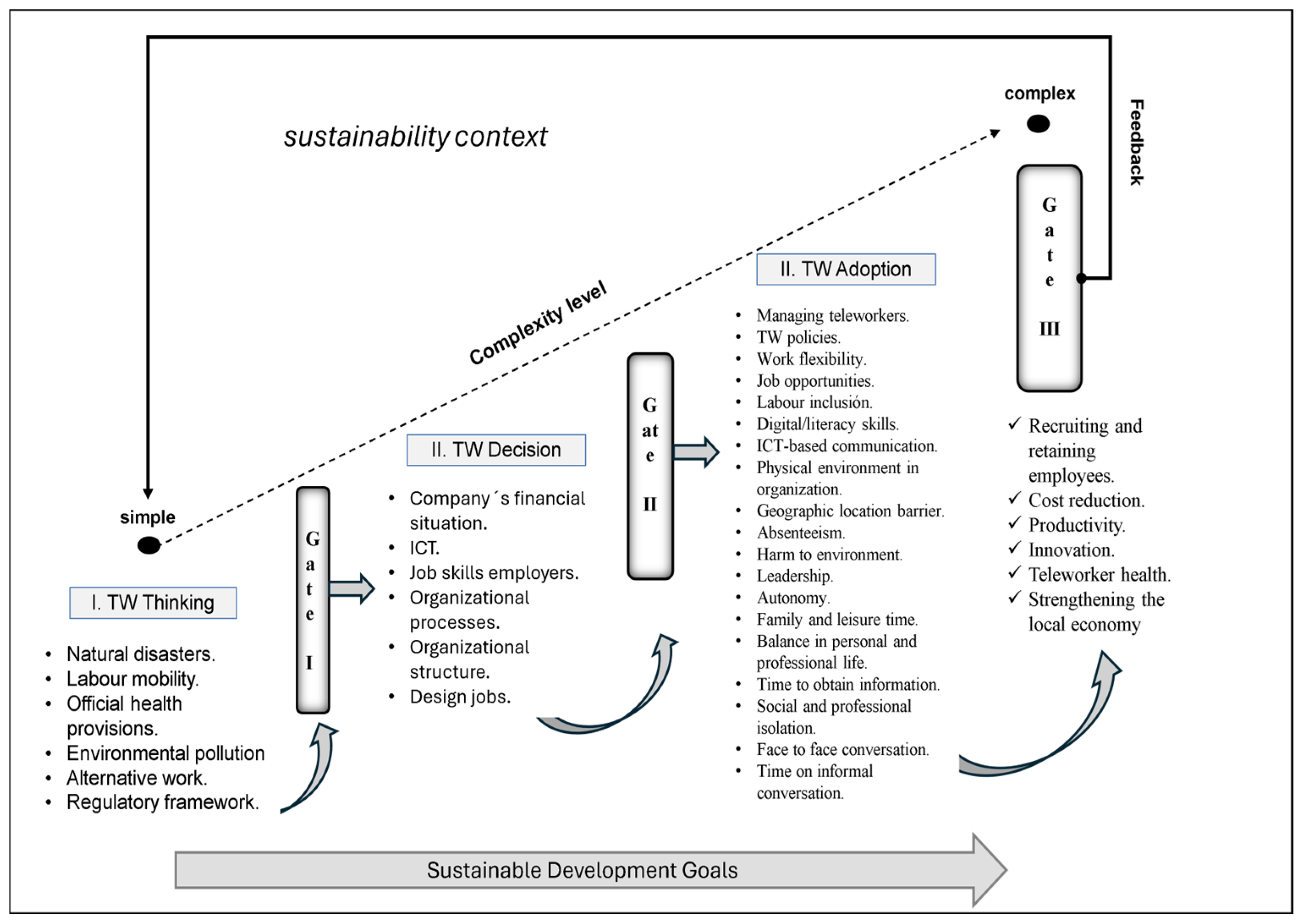

3.2. TW Adoption Sustainable Process

- Stage I. TW Thinking

- Gate I.

- Stage II. TW Decision

- Gate II

- Stage III. TW Adoption

- Gate III

3.3. TW-ASP Implications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Research Limitations

- Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TW | Telework or teleworking |

| TW-ASP | TW adoption sustainable process |

| HRM | Human resource management |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goalss |

| ICT | Information and communication technology |

References

- WEF. Global Risks Report 2025; WEF: Cologny, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- WHO. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- World Bank Group. World Bank Group Annual Reports; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Beham, B.; Baierl, A.; Poelmans, S. Managerial Telework Allowance Decisions—A Vignette Study among German Managers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.L.; Hyland, M.A.M. Role Conflict and Flexible Work Arrangements: The Effects on Applicant Attraction. Pers. Psychol. 2002, 55, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, K.; Cachat-Rosset, G.; Marsan, J.; Saba, T.; Klarsfeld, A. Adjusting to Epidemic-Induced Telework: Empirical Insights from Teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 30, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellaert, M.; Derous, E. Retirement Decisions in Times of COVID-19: The Role of Telework, ICT-Related Strain and Social Support on Older Workers’ Intentions to Continue Working. Pers. Rev. 2024, 53, 1950–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamani, Y.; Kajikawa, Y. How Teleworking Adoption Is Changing the Labor Market and Workforce Dynamics? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokan, T.; Kichko, S.; Matheson, J.; Thisse, J.-F. How the Rise of Teleworking Will Reshape Labor Markets and Cities; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair-Loy, M.; Wharton, A.S. Employees’ Use of Work-Family Policies and the Workplace Social Context. Soc. Forces 2002, 80, 813–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautsch, B.; Kossek, E. Managing a Blended Workforce: Telecommuters and Non-Telecommuters. Organ. Dyn. 2011, 40, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, Š.; Buzeti, J. Working in Public Administration During Nonwork Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cent. Eur. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 19, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.; Carinhana, D. Decision-Making Approach for Complex Problems Management in a Scarce Human Resources Environment. J. Model. Manag. 2021, 16, 1302–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahlyan, D.; Said, M.; Mahmassani, H.; Stathopoulos, A.; Walker, J.; Shaheen, S. For Whom Did Telework Not Work during the Pandemic? Understanding the Factors Impacting Telework Satisfaction in the US Using a Multiple Indicator Multiple Cause (MIMIC) Model. Transp. Res. Pt. A Policy Pract. 2022, 155, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglioretti, M.; Gragnano, A.; Margheritti, S.; Picco, E. Not All Telework Is Valuable. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. COVID-19: Guidance for Labour Statistics Data Collection; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Euroforum; ILO. Working Conditions in a Global Perspective; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen, M. Telework and Remote Work. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.850 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Kurkland, N.B.; Bailey, D.E. The Advantages and Challenges of Working Here, There Anywhere, and Anytime. Organ. Dyn. 1999, 28, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Rodrigues, H.; Freitas, P. “No Need to Dress to Impress” Evidence on Teleworking during and after the Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.S.; Santos, A.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Chambel, M.J. Please, Do Not Interrupt Me: Work–Family Balance and Segmentation Behavior as Mediators of Boundary Violations and Teleworkers’ Burnout and Flourishing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T. Human Capital: What It Is and Why People Invest It; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Phaladi, M. Human Resource Management as a Facilitator of a Knowledge-Driven Organisational Culture and Structure for the Reduction of Tacit Knowledge Loss in South African State-Owned Enterprises. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 24, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Taylor, S. Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Groen, B.A.C.; van Triest, S.P.; Coers, M.; Wtenweerde, N. Managing Flexible Work Arrangements: Teleworking and Output Controls. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyöriä, P. Managing Telework: Risks, Fears and Rules. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.; Yung, M.; Somasundram, K.G.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Oakman, J.; Yazdani, A. Working in the Digital Economy: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Work from Home Arrangements on Personal and Organizational Performance and Productivity. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Roloff, M.E. Why Teleworkers Are More Satisfied with Their Jobs than Are Office-Based Workers: When Less Contact Is Beneficial. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Dino, R.N. The Impact of Professional Isolation on Teleworker Job Performance and Turnover Intentions: Does Time Spent Teleworking, Interacting Face-to-Face, or Having Access to Communication-Enhancing Technology Matter? J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.A.; Patmos, A.; Pitts, M.J. Communication and Teleworking: A Study of Communication Channel Satisfaction, Personality, and Job Satisfaction for Teleworking Employees. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2018, 55, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, C.; Fortin, M.; Ohana, M.; German, H. Women’s Double Penalty During Telework: A Mixed Method Investigation of the Gender Effect of Interruptions Between Work and Childcare. Group Organ. Manag. 2024, 50, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembrechts, L.; Zanoni, P.; Verbruggen, M. The Impact of Team Characteristics on the Supervisor’s Attitude towards Telework: A Mixed-Method Study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 3118–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Merlo, K.; Buro, A.; Vereen, S.; Koeut-Futch, K.; Pelletier, C.; Ankrah, E. Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Home Visiting Workforce Wellbeing and Telework in Florida. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 155, 107306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenailleau, Q.; Tannier, C.; Vuidel, G.; Tissandier, P.; Bernard, N. Assessing the Impact of Telework Enhancing Policies for Reducing Car Emissions: Exploring Calculation Methods for Data-Missing Urban Areas-Example of a Medium-Sized European City (Besancon, France). Urban Clim. 2021, 38, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchiano, M.; Fernandez, G.; Widmer, E.; Arntz, M.; Azzi, M.; Bulti, A.; Cianferoni, N.; Cullati, S.; Junte, S.; Massoudi, K.; et al. The Empty Office: Protocol for Sequential Mixed-Method Study on the Impact of Telework Activities on Social Relations and Well-Being. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e089232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkyns, R.; Blazek, M.; Roitz, J.; AT&T. Measurement of Environmental Impacts of Telework Adoption amidst Change in Complex Organizations: AT&T Survey Methodology and Results. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2002, 36, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorulmaz, H.; Eti, S. Building Telework Capability in the New Business Era for SMEs, Using Spherical Fuzzy AHP Methodology for Prioritizing the Actions. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; Casper, W.; Raghuram, S. Crafting Telework: A Process Model of Need Satisfaction to Foster Telework Outcomes. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tian, H.; Kido, K.; Ono, N.; Chen, W.; Tamura, T.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.D.; Kanaya, S.; Huang, M. A Real-Time Portable IoT System for Telework Tracking. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 643042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanhokwe, H. Evaluating a Desire to Telework Model: The Role of Perceived Quality of Life, Workload, Telework Experience and Organisational Telework Support. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, C.-A.; Caraiani, C.; Anica-Popa, I.F.; Dascalu, C.; Lungu, C.I. Telework Systematic Model Design for the Future of Work. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilian, R.; Edrisi, A. Modeling Factors Affecting the Choice of Telework and Its Impact on Demand in Transportation Networks. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2020, 16, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Li, S.; Liu, H. The Impact Mechanism of Telework on Job Performance: A Cross-Level Moderation Model of Digital Leadership. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, M.; Ghilic-Micu, B.; Mircea, M. The telework paradigm in the ioe ecosystem—A model for the teleworker residence choice in context of digital economy and society. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. 2021, 55, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, V.; Vayre, E.; Molino, M.; Ghislieri, C. Far Away, So Close? The Role of Destructive Leadership in the Job Demands-Resources and Recovery Model in Emergency Telework. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kim, S.H.; Mokhtarian, P.L. Identifying Teleworking-Related Motives and Comparing Telework Frequency Expectations in the Post-Pandemic World: A Latent Class Choice Modeling Approach. Transp. Res. Pt. A Policy Pract. 2024, 186, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekman, E.; Van Hooff, M.; Adiasto, K.; Claessens, B.; van der Heijden, B. Is This (Tele)Working? A Path Model Analysis of the Relationship between Telework, Job Demands and Job Resources, and Sustainable Employability. Work 2025, 80, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Jeon, S. Why Permit Telework? Exploring the Determinants of California City Governments’ Decisions to Permit Telework. Public Pers. Manag. 2017, 46, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; McDonald, S. Do Networked Workers Have More Control? The Implications of Teamwork, Telework, ICTs, and Social Capital for Job Decision Latitude. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.; Hofer-Fischanger, K. Factors Associated with the Implementation of Health-Promoting Telework from the Perspective of Company Decision Makers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc. Pub.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.G. Perspective: The Stage-Gate® Idea-to-Launch Process—Update, What’s New, and Nexgen Systems. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; Mckenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/The World Bank. Fiscal Resilience to Natural Disasters: Lessons from Country Experiences; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, E. Efecto Checklist, El. Como Una Simple Lista de Comprobacion Elimina Errores y Salva Vidas; Antoni Bosch Editor: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelmaier, W.; Kress, S.; Wenski, R. TelCoW: Telework under the Co-Ordination of a Workflow Management System. Inf. Softw. Technol. 1999, 41, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Digital Skills Critical for Jobs and Social Inclusion. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/digital-skills-critical-jobs-and-social-inclusion (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Information Literacy. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/ifap/information-literacy (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Zamfir, A.-M.; Aldea, A.A. Digital Skills and Labour Market Resilience. Postmod. Open. 2020, 11, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.A.; Lauzun, H.M. Equipping Managers to Assist Employees in Addressing Work-Family Conflict: Applying the Research Literature toward Innovative Practice. Psychol. Manag. J. 2010, 13, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Does Remote Work Flexibility Enhance Organization Performance? Moderating Role of Organization Policy and Top Management Support. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, N.; Hauff, S.; Gubernator, P. The Joint Role of HRM and Leadership for Teleworker Well-Being: An Analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO/OECD. Equality Between Men and Women in the Workforce; G20 Technical Paper; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OIT. Competencias Para El Empleo, Orientaciones de Política—Mejorar La Empleabilidad de Los Jóvenes: La Importancia de Las Competencias Clave; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.P.; Sánchez, A.M.; de Luis Carnicer, M.P. Benefits and Barriers of Telework: Perception Differences of Human Resources Managers According to Company’s Operations Strategy. Technovation 2002, 22, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Zhou, Z.E.; Tang, H.; Ma, H.; Gan, Z. What It Takes to Be an Effective “Remote Leader” during COVID-19 Crisis: The Combined Effects of Supervisor Control and Support Behaviors. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 2901–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Boston, M. Residential Built Environment and Working from Home: A New Zealand Perspective during COVID-19. Cities 2022, 129, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, P.; Lopes, S.; Peixoto, R. Mastering New Technologies: Does It Relate to Teleworkers’ (in)Voluntariness and Well-Being? J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 2618–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.B.; Lee, D.; Sohn, H. How to Increase Participation in Telework Programs in U.S. Federal Agencies: Examining the Effects of Being a Female Supervisor, Supportive Leadership, and Diversity Management. Public Pers. Manag. 2019, 48, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Jeon, S.H. Do Leadership Commitment and Performance-Oriented Culture Matter for Federal Teleworker Satisfaction With Telework Programs? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2020, 40, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.M.; Hislop, D.; Cartwright, S. Social Support in the Workplace between Teleworkers, Office-Based Colleagues and Supervisors. New Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R.P.; Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A. A Within-Person Examination of the Effects of Telework. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Maguire, S.; McKelvey, B. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall, W.; Gao, L. An Update on Telecommuting: Review and Prospects for Emerging Issues. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2005, 70, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell, G.; Taskin, L. Out of Sight, Out of Mind in a New World of Work? Autonomy, Control, and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically Reviewing Remote E-Workers’ Well-Being at Work: A Multidimensional Approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.J.; Rubino, C.; Hunter, E.M. Stress in Remote Work: Two Studies Testing the Demand-Control-Person Model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.T.; Anwar, I.; Khan, N.A.; Ahmad, G. How Do Teleworkers Escape Burnout? A Moderated-Mediation Model of the Job Demands and Turnover Intention. Int. J. Manpow. 2023, 45, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisiene, A.G.; Danauske, E.; Kavaliauskiene, K.; Gudzinskiene, V. Occupational Stress-Induced Consequences to Employees in the Context of Teleworking from Home: A Preliminary Study. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.; Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Telework, Hybrid Work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: Towards Policy Coherence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illegems, V.; Verbeke, A. Telework: What Does It Mean for Management? Long Range Plan. 2004, 37, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, I. Advantages and Disadvantages of Telecommuting for the Individual, Organization and Society. Work Study 2002, 51, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi-Legaz, S.; Núñez, I.; Ollo-López, A. Home-Based Telework and Job Stress: The Mediation Effect of Work Extension. Pers. Rev. 2023, 53, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown about Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čiarnienė, R.; Vienažindienė, M.; Adamonienė, R. Teleworking and Sustainable Behaviour in the Context of COVID-19: The Case of Lithuania. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2023, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; International Monetary Fund. El Teletrabajo Impulsa la Productividad. Available online: https://www.imf.org/es/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/09/working-from-home-is-powering-productivity-bloom#:~:text=El%20teletrabajo%20facilita%20el%20emparejamiento,contaminaci%C3%B3n%20provocada%20por%20el%20transporte (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Oviedo-Gil, Y.M.; Cala Vitery, F.E. Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Developmental Goals, 2023; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking. In Rethinking Management Information Systems: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; OUP: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| TW Thinking | TW Decision | TW Adoption | |

|---|---|---|---|

| -Natural disasters. -Labour mobility. -Official health provisions. -Environmental pollution. -Alternative work. -Regulatory framework. | -Company’s financial situation. -ICT. -Job skills. -Employers. -Organizational processes. -Organizational structure. -Design jobs. | -Managing teleworkers. -TW policies. -Work flexibility. -Job opportunities. -Labour inclusion. -Digital/literacy skills. -ICT-based communication. -Physical environment in organization. -Geographic location barrier. -Absenteeism. -Harm to environment. -Leadership. -Autonomy. -Family and leisure time. -Balance in personal and professional life. -Time to obtain information. -Social and professional isolation. -Face-to-face conversation. | -Time on informal conversation. -Belonging in the workplace. -Collaboration. -Creativity. -Time and cost of travel. -Job satisfaction. -Work exhaustion. -Stress. -Engagement. -Organizational culture and identity. -Recruiting and retaining employees. -Cost reduction. -Productivity. -Innovation. -Teleworker health. -Strengthening the local economy. |

| Variable | Context for TW | TW Thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Are there official health provisions? | Positive | Yes |

| Is it possible to adopt alternative working methods other than face-to-face? | Positive | Yes |

| Is there a regulatory framework for TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Are there conditions that favour labour mobility? | Positive | Yes |

| Are there conditions that contribute to an increase in environmental pollution levels? | Positive | Yes |

| Are there conditions that increase the likelihood of a natural disaster? | Positive | Yes |

| Variable | Variable Condition | TW Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| What is company’s financial situation for TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Can organizational processes be carried out remotely? | Positive | Yes |

| Does organizational structure enable TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Is there an adequate organizational infrastructure for information and communication technology available for TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Do workers possess required job skills for TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Do company policies promote your well-being and that of your employees by adopting TW? | Positive | Yes |

| Variable | Condition of Variable | TW Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| Does organizational culture and identity favour TW in the company? | Positive | Yes |

| Does adopting TW in the company boost innovation capacity? | Positive | Yes |

| Does adopting TW promote productivity in the company? | Positive | Yes |

| Does adopting TW contribute to cost reduction in the company? | Positive | Yes |

| Does adopting TW in the company increase employees recruiting and retaining? | Positive | Yes |

| Does adopting TW in the company promote teleworker health? | Positive | Yes |

| Does TW in the company contribute to strengthening local economy? | Positive | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguilar-Fernández, M.; Salgado-Escobar, G.; León-Romero, L.P.; García-Jarquín, B.; Francisco-Márquez, M. A Three-Stage Process for Sustainable Telework Adoption. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209356

Aguilar-Fernández M, Salgado-Escobar G, León-Romero LP, García-Jarquín B, Francisco-Márquez M. A Three-Stage Process for Sustainable Telework Adoption. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209356

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguilar-Fernández, Mario, Graciela Salgado-Escobar, Luvis P. León-Romero, Brenda García-Jarquín, and Misaela Francisco-Márquez. 2025. "A Three-Stage Process for Sustainable Telework Adoption" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209356

APA StyleAguilar-Fernández, M., Salgado-Escobar, G., León-Romero, L. P., García-Jarquín, B., & Francisco-Márquez, M. (2025). A Three-Stage Process for Sustainable Telework Adoption. Sustainability, 17(20), 9356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209356

_Li.png)