The Role of Social Initiatives in Shaping Sustainable Business Outcomes—Insights from Organizations Operating in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- Which types of social activities undertaken by organizations are most strongly associated with sustainable outcomes?

- RQ2:

- To what extent do the eight identified social constructs (SOC1–SOC8) contribute to explaining variance in sustainable outcomes?

- RQ3:

- Are particular areas of social engagement (e.g., creating value for society, embedding social aspects in the value chain) more effective predictors of sustainable outcomes than others?

- RQ4:

- How can the TLBMC model be used as a practical tool to reveal the social awareness of employees?

2. Theoretical Framework: The Three Dimensions of Sustainability in the TLBMC

2.1. The Economic Layer Based on the Original BMC

2.2. Environmental Life Cycle Layer

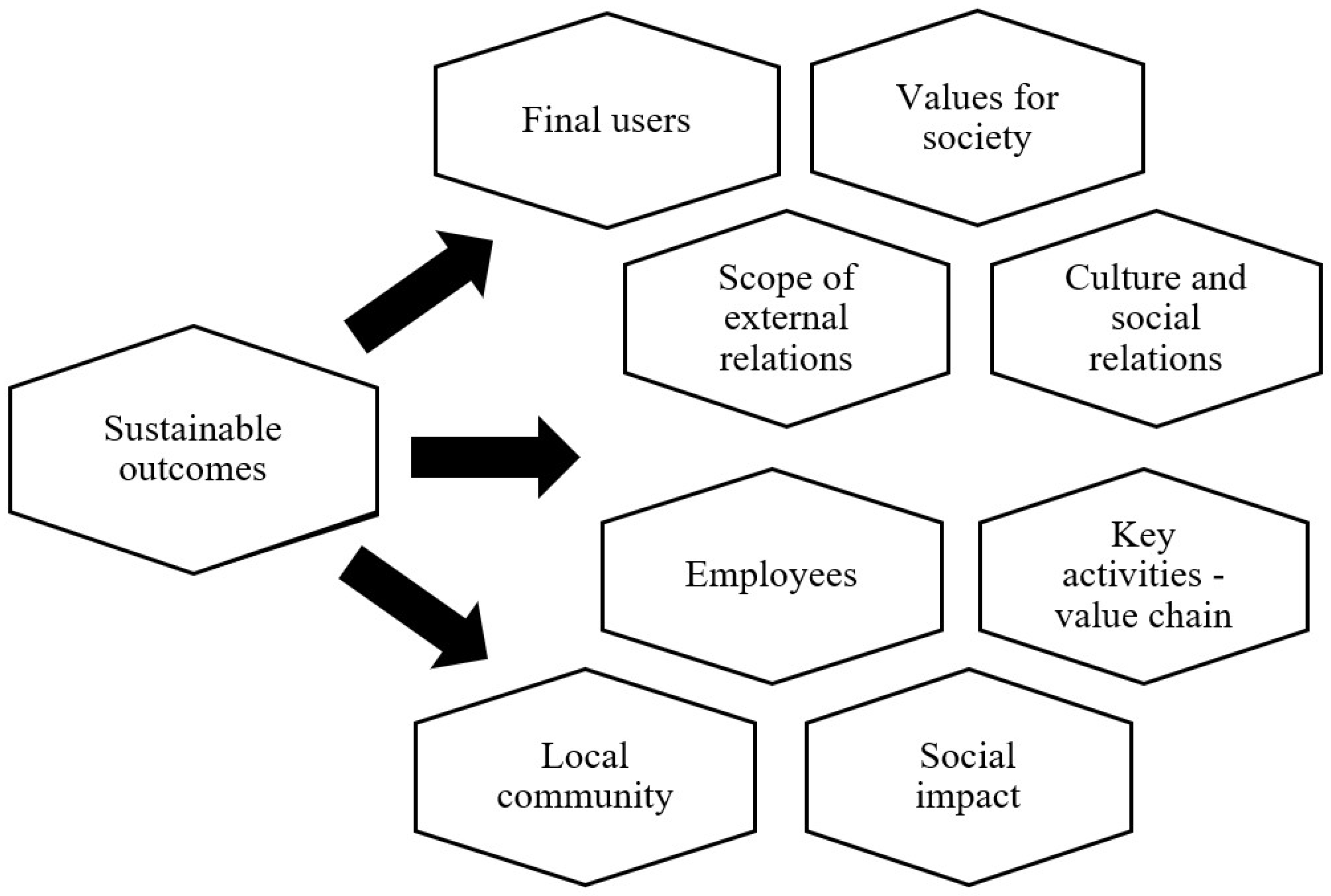

2.3. The Social Layer

2.4. Comparison and Integration of the Three Dimensions of Sustainability

3. Activities in the Social Area and Sustainable Results

3.1. Final Users

3.2. Values for Society

3.3. Scope of External Relations

3.4. Culture and Social Relations

3.5. Employees

3.6. Key Activities—Value Chain

3.7. Local Community

3.8. Social Impact

- H1: Activities aimed at improving human health and safety, ensuring access to resources, promoting fair competition, respecting intellectual property rights, and educating communities (SOC1) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H2: Supporting socially active attitudes, stakeholder cooperation, unemployment reduction, anti-discrimination measures, diversity promotion, and societal well-being initiatives (SOC2) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H3: Fostering long-term customer relationships, building social capital, promoting environmental awareness, and respecting cultural diversity (SOC3) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H4: Building corporate reputation, fostering trust and a positive brand image, enhancing customer loyalty, and promoting sustainable consumption (SOC4) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H5: The implementation of ethical conduct, employee development, occupational health and safety, diversity management, work–life balance, and employee participation (SOC5) positively influences sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H6: The integration and alignment of pre-production, production, logistics, marketing, and post-sales activities (SOC6) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H7: The sustainable management of local resources, infrastructure support, cultural heritage preservation, and the integration of local and migrant workers (SOC7) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

- H8: Comprehensive social responsibility initiatives addressing employees, local communities, supply chain participants, consumers, society, and children (SOC8) positively influence sustainable outcomes (OUT).

4. Methodology

5. Conclusions

6. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacłona, R.; Brzezińska, K.; Susik, K.; Schatt Babińska, K. Co Nam Daje CSR? Dobre Praktyki; Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-7633-317-5.

- Dąbrowski, T.J.; Majchrzak, K. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność i Nieodpowiedzialność Biznesu. Przyczyny, Przejawy, Konsekwencje Ekonomiczne; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-8030-542-7. [Google Scholar]

- Merta-Staszczak, A.; Walecka-Jankowska, K. Social Dimension of Sustainable Development and Social Outcomes of Businesses. Stud. Logic, Gramm. Rhetor. 2024, 69, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, Y.; Naro, G. Le Triple Layered Business Model Canvas ou la construction cohérente d’une triple valeur: Le cas de l’industrie automobile du futur. In Proceedings of the 32ème Congrès de l’Association Internationale de Management Stratégique, Strasbourg, France, 6–9 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mili, S.; Loukil, T. Enhancing sustainability with the triple-layered business model canvas: Insights from the fruit and vegetable industry in Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, V.; Sirait, T.; Ramauli, J. Business Development Strategy Design Using TLBMC: Case of MDC Coffee House. Int. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2024, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Paquin, R.L.; Busch, T.; Tilleman, S.G. Creating economic and environmental value through industrial symbiosis. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.; Osmani, M.; Grubnic, S.; Díaz, A.I.; Grobe, K.; Kaba, A.; Ünlüer, Ö.; Panchal, R. Implementing a circular economy business model canvas in the electrical and electronic manufacturing sector: A case study approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 36, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasyd, M.R.A.; Mulyadi, H.; Utama, D.H.; Furqon, C.; Twum, S. Sustainability in coffee shops: A triple-layered business model canvas approach. Int. J. Entrep. Sustain. Stud. 2025, 5, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwin, M.; Jacyna-Gołda, I.; Kraslawski, A.; Waszkiewicz, A.E. The use of business model canvas in the design and classification of product-service systems design methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoussohoui, R.; Arouna, A.; Bavorova, M.; Tsangari, H.; Banout, J. An extended Canvas business model: A tool for sustainable technology transfer and adoption. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.J.; O’Connell, M.S.; Reeder, M.; Nigel, R. Predicting and Improving Safety Performance; Industrial Management: Norcross, GA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nagyova, A.; Balazikova, M.; Markulik, S.; Sinay, J.; Pacaiova, H. Implementation proposal of OH&S management system according to the standard ISO/DIS 45001. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Cham, Switzerland, 17–21 July 2017; pp. 472–485. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, M. Social dimension of sustainability in CSR standards. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 4800–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivic, A.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Johannsdottir, L. Drivers of sustainability practices and contributions to sustainable development evident in sustainability reports of European mining companies. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Haider, M.B.; Islam, M.T. Revisiting Corporate Social Disclosure in JAPAN; Palgrave Macmillan Asian Business Series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Terchilă, S. Integrating CSR in external communication strategies: Economic and social impact. In CSR, Sustainability, Ethics and Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage, J.P. Sustainability concept and complex performance dimensions. In Value Networks in Manufacturing; Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Primorac, D. Analysis of socially responsible business in the area of Podravina. Podravina 2024, 23, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Ramaswamy, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Grandhi, B.; Chaudhuri, S.; Chatterjee, S. Harmonious CSR and sustainable business excellence in sports-organization: Evaluating the moderating effect of fan engagement. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, M.; Dawar, S.; Soni, A. Probing consumer awareness & barriers towards consumer social responsibility: A novel sustainable development approach. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Alam, K.; Kabir, E. Modelling corporate stakeholder orientation: Does the relationship between stakeholder background characteristics and corporate social performance matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Boesso, G.; Kumar, K. Examining the link between strategic corporate social responsibility and company performance: An analysis of the best corporate citizens. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppura, A.; Toppinen, A.; Jantunen, A. Proactiveness and corporate social performance in the global forest industry. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, J.; Mahajan, V. Driven to be good: A stakeholder theory perspective on the drivers of corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills Cox, B. Aligning CSR, DEI, and public relations: Analyzing top consumer brands and their implementation of DEI practices. Howard J. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, E. Advancing human and social dimensions in balanced scorecards for GCC corporations: A nuanced approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2024, 12, 2398737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Evandio, D.Y.; Riantono, I.E. Corporate governance and ESG strategies: The moderating impact of internal audit quality on financial performance in Indonesian companies. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 9, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, B.V.; Kim, S.; Bell, M.; Frantz, N. Global country social responsibility: What is it? An abstract. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, S.S. Assessment of social sustainability management in various industrial sectors. In Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi, M.H. Social responsibility pressure as a motivator for organizational sustainability: Evidence from the fast-food sector in KSA. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2025, 12, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.X.; Nguyen, P.V.; Nguyen, S.T.N. Enhancing sustainable business performance through environmental regulations, corporate social responsibility and green human resources management and green employee behaviour in Vietnam’s hospitality industry. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2025, 30, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Fernandez, M.; Lopez-Cabrales, A.; Valle-Cabrera, R. Sustainable strategies, employee competencies and social outcomes: Are they aligned? Int. J. Manpow. 2024, 45, 1426–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shuridah, O.M.; Ndubisi, N.O. The effect of sustainability orientation on CRM adoption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, S.A.; Alanazi, T.M. The mediating role of sustainable dynamic capabilities in the effect of social customer relationship management on sustainable competitive advantage: A study on SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Samad, S.; Kim, W.; Wei, F. From corporate responsibility to green loyalty: How CSR initiatives shape sustainable choices among banking consumers in China. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, G.; Dash, P.; Jogalekar, J.; Killedar, M.; Rao, M.S.; Biswas, M. Corporate social responsibility: Economic impacts on consumer loyalty and brand value in the digital era. Econ.-Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2025, 13, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, E. Social and personal norms in shaping customers’ environmentally sustainable behavior in restaurants’ social media communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Li, Y.; Hussain, H. Sustainability beyond profits: Assessing the impact of corporate social responsibility on strategic business performance in hospitality small and medium enterprises. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonca, T.R.; Zhou, Y. Environmental performance, customer satisfaction, and profitability: A study among large U.S. companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalinda, C.; Idris, I.; Susanto, P. Driving SME’s towards green business: The impact of sustainable marketing mix on performance and loyalty in BNI’s Go Green Movement. J. Ecohuman. 2024, 3, 4190–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D.; Paul, M. Managing service relationships in a global economy: Exploring the impact of national culture on the relevance of customer relational benefits for gaining loyal customers. Adv. Int. Mark. 2004, 15, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sannino, G.; Lucchese, M.; Zampone, G.; Lombardi, R. Cultural dimensions, Global Reporting Initiatives commitment, and corporate social responsibility issues: New evidence from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Akram, R.; Hieu, V.M.; Tien, N.H. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the sustainable financial performance of Italian firms: Mediating role of firm reputation. Econ. Res.–Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 4740–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurage-Altenloh, S.; Randall, P.M. The influence of CSR on B2B relationships: Leveraging ethical behaviors to create value. In Examining Ethics and Intercultural Interactions in International Relations; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xuetong, W.; Hussain, M.; Rasool, S.F.; Mohelska, H. Impact of corporate social responsibility on sustainable competitive advantages: The mediating role of corporate reputation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46207–46220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroensombut, L.; Yiengthaisong, A.; Sakolnakorn, T.P.N. Corporate social responsibility management for sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2025, 12, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, K.; Shah, S.H.A.; Durrah, O. How corporate responsibility influences organizational performance: An overview on the role of green transformational leadership. In Strategies and Approaches of Corporate Social Responsibility Toward Multinational Enterprises; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A. Investigating the intersection of organizational behavior, supply chain practices, economic outcomes, financial excellence and CSR for corporate identity improvement. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2025, 29, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezahegn, M.A.; Durie, A.D.; Kibret, A.T. Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in Ethiopian banking sector. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2025, 33, 1702–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.H.; Liang, W.C. Exploring the determinants of strategic corporate social responsibility: An empirical examination. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajadi, T.H.; Adisa, O.; Goyol, M.; Adisa, O.M. The interplay between ethical work climate and employee mental health: A critical analysis. In Advances in Ethical Work Climate and Employee Well-Being; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, T.S.; Ramakrishnan, P.R. Employee perception towards workplace ethics: A study on manufacturing industries in Chennai. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Automation and Computation, AUTOCOM 2025, Dehradun, India, 4–6 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell, J.J. Concluding comments. In Workplace Well-Being: How to Build Psychologically Healthy Workplaces; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grawitch, M.J.; Gottschalk, M.; Munz, D.C. The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consult. Psychol. J. 2006, 58, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, A.; De Stefano, F.; Paolino, C. Safety reloaded: Lean operations and high involvement work practices for sustainable workplaces. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixafenti, S.; Karagkouni, A.; Dimitriou, D. Integrating business ethics into occupational health and safety: An evaluation framework for sustainable risk management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, E.; Kwiatek, A. Psychosocial security of employees in the work environment in the context of diversity management. Syst. Saf.-Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W. How does sustainability-oriented human resource management work? Examining mediators on organizational performance. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.L.; Lombardi, G.H.V.; Pimenta, M.L. Cross-functional alignment: An exploratory study on the points of contact among marketing, logistics, and production. Gestão Produção 2013, 20, 863–881. [Google Scholar]

- Springinklee, M.; Wallenburg, C.M. Improving distribution service performance through effective production and logistics integration. J. Bus. Logist. 2012, 33, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlacu, O.S.; Turek Rahoveanu, M.M. Logistics’ role in the sustainable development of a multinational company. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2019: Education Excellence and Innovation Management Through Vision 2020, Granada, Spain, 10–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekar, D.; Bhuvaneswari, K.; Aruneshwar, D.K. An empirical study on the going backwards of reverse logistics trends and practices. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Yan, Y.; Wu, Z.Z. Determinants of the transition towards circular economy in SMEs: A sustainable supply chain management perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 16865–16883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Siddik, A.B.; Zheng, G.W.; Masukujjaman, M. Unveiling the role of green logistics management in improving SMEs’ sustainability performance: Do circular economy practices and supply chain traceability matter? Systems 2023, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F.H.; Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Mustafa, S.; Atif, M.; Gul, R.F.; Guangyu, Q. Mediating role of green supply chain management between lean manufacturing practices and sustainable performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 810504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Vo, X.V.; Venkatesh, V.G. Role of green innovation and supply chain management in driving sustainable corporate performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 133875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M.; Talib Bon, A. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, Y.; Thorpe, M.; Yoshida, S. The shift from after-sales service to design servicing competence: A study of the manufacture of sanitary ware and their integration of sustainable technologies. In Proceedings of the 2012 Portland International Center for Management of Engineering and Technology: Technology Management for Emerging Technologies, PICMET’12, Vancouver, BA, Canada, 29 July–2 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lavi, O.S. Corporate social responsibility: Marketing in the global world. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, A.; Yaacob, M.R.; Ismail, M.B.; Mohd Radyi, S.A. Corporate engagement with the community: Building relationships through CSR. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 1538–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Kulej-Dudek, E.; Dudek, D. Good practices of corporate social responsibility of Polish enterprises in the aspect of ESG. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 5234–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, F. Corporate Responsibility for Cultural Heritage: Conservation, Sustainable Development, and Corporate Reputation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, R.H.; Palma, A.; Hoagland-Grey, H. Community investment programs in developing country infrastructure projects. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2008, 14, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz Palafox, K.H. Responsabilidad social como motor de la sostenibilidad en economías emergentes. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2025, 31, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tawiah, V.; Samson, N.; Jatau, U. Local directors and corporate social responsibility activities of multinational companies in Africa. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordham, A.E.; Robinson, G.M.; Blackwell, B.D. Corporate social responsibility in resource companies–Opportunities for developing positive benefits and lasting legacies. Resour. Policy 2017, 52, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordham, A.E.; Robinson, G.M.; Van Leeuwen, J. Developing community based models of corporate social responsibility. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2018, 5, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukuya, T.; Nyambiya, H.; Mutyandaedza, B. Local communities and protected areas: The case of Great Zimbabwe and Khami Ruins world heritage properties. In Community Development Insights on Cultural Heritage Tourism; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, L.J.; Litheko, A.; Pasco, M.; Butac, S.R.; Ramírez-Correa, P.; Salazar-Concha, C.; Magnait, C.P.T. Examining the role of organizational culture on citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of environmental knowledge and attitude toward energy savings. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Gurtu, A.; Vyas, V. Analysis of supply chain performance under the influence of social sustainability initiative of organizations. Oper. Supply Chain. Manag. 2025, 18, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.U. Harnessing collective power: Multi-stakeholder synergies for sustainable supply chain transformation. In Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainable Supply Chain; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhar, M. Enhancing Social Sustainability in Manufacturing Supply Chains; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.L.; Chong, S.C.; Wong, K.K.S. Sustainable development goals and corporate financial performance: Examining the influence of stakeholder engagement. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2714–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A. Model Zrównoważenia Przedsiębiorstwa; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bojar, E.; Bogdan, W. Triple bottom line w szablonie modelu biznesu A. Osterwaldera i Y. Pigneura w perspektywie interesariuszy. Zeszyty Naukowe Organizacja i Zarządzanie/Politechnika Śląska 2016, 99, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk, J. Zrównoważony rozwój jako paradygmat współczesnego zarządzania przedsiębiorstwem. Przegląd Organ. 2018, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L. Cognitive frames in corporate sustainability: Managerial sensemaking with paradoxical and business case frames. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 218–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Block | Description |

|---|---|

| Customer Segments | Defines the groups of customers the company serves and creates value for. |

| Value Proposition | Describes how the company solves a problem or satisfies a customer need. |

| Channels | Explains how the company communicates with and delivers value to customers. |

| Customer Relationships | Defines the types of relationships established with customer segments. |

| Revenue Streams | Identifies how the company earns revenue from its customer segments. |

| Key Resources | Lists the essential assets required to make the business model work. |

| Key Activities | Describes the critical actions needed to deliver value and maintain operations. |

| Key Partners | Identifies external parties that support the business model’s effectiveness. |

| Cost Structure | Outlines the major costs required to operate the business. |

| Block | Description |

|---|---|

| Materials | Type and quantity of raw materials used in production. |

| Energy Sources | Types and use of energy in direct and indirect operations. |

| Emissions | Emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants. |

| Functional Value | Evaluation of the sustainability performance during product use. |

| Product–Service Systems | Strategies to reduce environmental impact by changing usage models. |

| Durability | Product lifespan, reuse, repair, refurbishment, and recycling potential. |

| Closed-Loop Systems | Actions supporting material cycle closure. |

| Transport and Logistics | Environmental impact of logistics and distribution. |

| Infrastructure | Environmental impact of buildings, machinery, and equipment. |

| Block | Description |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Segments | Focus on stakeholders such as employees, local communities, NGOs, public institutions, and marginalized groups. |

| Social Value Proposition | Enhancing community well-being, promoting equity, supporting education and health, and creating decent jobs. |

| Social Engagement Channels | Community consultations, participatory platforms, CSR reports, and NGO dialogues. |

| Social Relationships | Nature of relationships with stakeholder groups—from employee relations to cooperation with community actors. |

| Social Value Streams | Tangible and intangible value generated by the organization for society. |

| Social Resources | Tangible and intangible assets enabling social actions—e.g., human capital, trust, local knowledge, reputation. |

| Social Activities | Key actions aimed at generating social value. |

| Social Partners | Institutions and organizations that collaborate on social objectives. |

| Social Costs/Investments | Costs incurred for social stakeholders—e.g., training, inclusion campaigns, compensations, and ethical actions. |

| Block | Economic Layer (ECO) | Environmental Layer (ENV) | Social Layer (SOC) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Segments | Customer groups to whom value is delivered | Entities impacting the environment across the life cycle | Communities, vulnerable groups, social stakeholders | Joyce & Paquin [5] |

| Value Proposition | Product or service that addresses a customer need | Environmental impact, sustainable functional benefits | Ethical value, social justice, human dignity | Joyce & Paquin [5] Mili & Loukil [8] Gómez & Naro [7] |

| Channels | Distribution and communication with the customer | Environmental footprint of logistics and distribution channels | Service accessibility for social groups, digital exclusion | Pollard et al. [11] Pane et al. [9] |

| Customer Relationships | Type of relationship—personal, automated, loyalty-based | Environmental education, informed consumer choices | Involving customers in the social mission, trust | Joyce & Paquin [5] Salwin et al. [13] |

| Revenue Streams | Revenue sources (sales, subscriptions, services) | Revenues from sustainable products/services, environmental charges | Crowdfunding, value for local communities | Paquin et al. [10] Pane et al. [9] |

| Key Resources | Infrastructure, people, IP, logistics | Low-footprint, renewable, and recyclable resources | Social capital, human resources from vulnerable groups | Amoussohoui et al. [14] |

| Key Activities | Production, marketing, customer service | Eco-design, life cycle assessment (LCA), resource efficiency | Social partnerships, educational and inclusive activities | Pollard et al. [11] Joyce & Paquin [5] |

| Key Partners | Suppliers, distributors, strategic allies | Environmentally certified partners, industrial symbiosis (IS), circular economy (CE) | NGOs, social entities, local organizations | Paquin et al. [10] Mili & Loukil [8] |

| Cost Structure | Fixed, variable, and unit costs | Environmental costs, investments in clean technologies | Costs of training, social integration, occupational safety | Joyce & Paquin [5] Gómez & Naro [7] Amoussohoui et al. [14] |

| Enterprise Size (Number of Employees) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Micro (Less Than 10) |

Small Enterprises (10–49) |

Medium (50–249) |

Large (Over 250) |

| 133 | 83 | 60 | 27 |

| Variable | Description (Variables Were Assessed on 5-Point Likert Scale) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Final users SOC1 | Includes (among others) activities to improve human health and safety, ensure access to resources, promote fair competition, respect intellectual property rights, nurture quality, educate communities, and reduce negative impacts. | 0.907 (25 items) |

| Values for society SOC2 | Includes (among others) activities like supporting/creating socially active attitudes, initiating cooperation between stakeholders, reducing unemployment, preventing discrimination in the workplace, caring for diversity, and caring for the betterment of society. | 0.948 (22 items) |

| Scope of external relations SOC3 | Includes (among others) activities like emphasizing the establishment of long-term customer relationships, building social capital through collaboration, integration, fostering environmental awareness, and aspiring to approach customers with respect regardless of their culture and country of origin, while actively promoting cultural diversity both in customer relations and within the internal structure. | 0.828 (17 items) |

| Culture and social relations SOC4 | Includes (among others) values like the trust in the enterprise and its recognition, along with the company’s reputation and commitment to resolving customer issues, presenting comprehensive and up-to-date information about its offerings, and providing fair solutions for handling customer complaints, grievances, and concerns, which are all integral aspects. Moreover, the safeguarding of customers’ personal data and privacy, an environmentally conscious orientation, access to reliable information about the company’s offerings and activities, protection of data after product usage, and the creation of shared values and social capital contribute to reinforcing democracy and fostering a culture of sharing. The company adheres to the concept of corporate social responsibility, supports sustainable consumption, and nurtures individualism among its customers. | 0.952 (23 items) |

| Employees SOC5 | Includes (among others) activities that are important to employees: promoting ethical conduct; emphasizing employee development through training, professional growth, and career advancement; adherence to occupational health and safety standards; fair treatment of employees; mutual trust; providing a work–life balance by respecting working hours, offering flexible schedules, and diverse employment arrangements; participation in decision-making; and inclusion and diversity management. | 0.924 (15 items) |

| Key Activities— Value Chain SOC6 | The pre-production activities, including research and development, product design, procurement of raw materials, components, energy, and equipment, fall under the purview of internal logistics, encompassing the receipt of transportation from suppliers, warehousing, and the distribution of raw materials, materials, and components to factories, assembly lines, warehouses, and shops. The transformation of raw materials into finished goods into products, packaging, and machine maintenance constitute the manufacturing process, while external logistics encompasses preparing offers, order receipt and dispatch, and delivery planning. Marketing and sales encompass pricing, and service involves maintaining the efficient operation of products post-sale and delivery. | 0.939 (21 items) |

| Local community SOC7 | The focus on local material resources involves sustainable resource sharing, protection, and enhancement of their quantity and quality. Additionally, attention is given to local infrastructure such as roads and schools, as well as the care of intangible local resources by promoting social services like education and healthcare. Improvement of access to knowledge and technology through sharing these resources with the local community; integration of migrating workers; communication, education, and legal assistance; and preservation of the cultural heritage of the local community by safeguarding cultural objects, social, and religious practices and promoting traditional crafts and products are also integral aspects. Furthermore, there is an emphasis on environmental risk management; stakeholder inclusion in strategies impacting the local environment, health, or well-being of the local community; and engagement, including financial support, in social initiatives. The commitment extends to the care of local employment, encompassing suppliers and workers. | 0.913 (17 items) |

| Social impact SOC8 | The staff (e.g., through improving human health, enhancing safety, and flexible working hours), the local community (e.g., through access to material resources, preservation of cultural heritage, involvement of local community participants excluding consumers (e.g., through promoting fair competition, corporate social responsibility, and respecting intellectual property rights), consumers (e.g., through ensuring return policies, ensuring quality, personal data, and transparency), society at large (e.g., through sustainable development, influencing economic development, and developing and transferring technology), and children (e.g., through education for local communities and reducing the impact on children’s health) are all part of the company’s comprehensive social responsibility initiatives. | 0.956 (15 items) |

| Sustainable outcomes OUT | Compared to competitors, the company’s performance in the following areas can be assessed in terms of relative advantage or disadvantage (in three sustainability dimensions): revenues; productivity (low costs); quality (solidity, reliability, and diligence), return on investment (ROI); profitability of the enterprise; number of new products and/or services successfully implemented; investments made in regions with high unemployment (poverty); availability of products or services for people with the lowest incomes; emissions; wastewater; waste; use of hazardous, toxic, harmful materials; total resource consumption (materials, energy, and water); environmental impact of products or services sold; impact on biodiversity; employee satisfaction; employee turnover; occupational health and safety; and customer satisfaction. Key factors considered include the company’s contribution to the development of healthy and sustainable communities, as well as the compliance of its suppliers with social and environmental criteria. | 0.945 (20 items) |

| OUT | SOC1 | SOC2 | SOC3 | SOC4 | SOC5 | SOC16 | SOC7 | SOC8 | |

| Pearson Corr. | 0.469 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.510 ** | |

| Sign. bilateral | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| N | 303 | 303 | 303 | 303 | 303 | 303 | 303 | 303 |

| Coefficients a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Standardized

Coefficients | Standardized | |||||

| Model | Standard Error | Coefficients | t | Significance | ||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.649 | 0.148 | 11.120 | <0.001 | |

| SOC1 | 0.060 | 0.039 | 0.105 | 1.544 | 0.124 | |

| SOC2 | 0.104 | 0.037 | 0.188 | 2.814 | 0.005 | |

| SOC3 | 0.040 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.716 | 0.474 | |

| SOC4 | 0.035 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.694 | 0.488 | |

| SOC5 | 0.044 | 0.031 | 0.087 | 1.447 | 0.149 | |

| SOC6 | 0.120 | 0.047 | 0.174 | 2.540 | 0.012 | |

| SOC7 | 0.015 | 0.025 | 0.033 | 0.618 | 0.537 | |

| SOC8 | 0.060 | 0.033 | 0.122 | 1.829 | 0.068 | |

| Hypothesis | Description (SOC Variable) | Result | Verification |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 (SOC1) | Final users (health and safety, access to resources, fair competition, and education) | Moderate correlation (r = 0.469), not significant in regression | Not supported |

| H2 (SOC2) | Values for society (CSR, DEI, stakeholder cooperation, and anti-discrimination) | Strong correlation (r = 0.505), significant predictor ( = 0.188, p = 0.005) | Supported |

| H3 (SOC3) | Scope of external relations (long-term customer relationships, cultural diversity, and green marketing) | Moderate correlation (r = 0.444), not significant in regression | Not supported |

| H4 (SOC4) | Culture and social relations (reputation, trust, and sustainable consumption) | Moderate correlation (r = 0.422), not significant in regression | Not supported |

| H5 (SOC5) | Employees (ethics, development, OHS, work–life balance, and participation) | Moderate correlation (r = 0.367), not significant in regression | Not supported |

| H6 (SOC6) | Key activities–value chain (production, logistics, marketing, and after-sales) | Strong correlation (r = 0.504), significant predictor ( = 0.174, p = 0.012) | Supported |

| H7 (SOC7) | Local community (resources, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and integration) | Low correlation (r = 0.256), not significant in regression | Not supported |

| H8 (SOC8) | Social impact (comprehensive CSR, supply chain, consumers, society, and children) | Strong correlation (r = 0.510), borderline predictor ( = 0.122, p = 0.068) | Partially supported (on significance threshold) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walecka-Jankowska, K.; Wasilewska, B.; Wasilewski, A. The Role of Social Initiatives in Shaping Sustainable Business Outcomes—Insights from Organizations Operating in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209357

Walecka-Jankowska K, Wasilewska B, Wasilewski A. The Role of Social Initiatives in Shaping Sustainable Business Outcomes—Insights from Organizations Operating in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209357

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalecka-Jankowska, Katarzyna, Barbara Wasilewska, and Adam Wasilewski. 2025. "The Role of Social Initiatives in Shaping Sustainable Business Outcomes—Insights from Organizations Operating in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209357

APA StyleWalecka-Jankowska, K., Wasilewska, B., & Wasilewski, A. (2025). The Role of Social Initiatives in Shaping Sustainable Business Outcomes—Insights from Organizations Operating in Poland. Sustainability, 17(20), 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209357