Non-Formal Education on Sustainable Tourism for Local Stakeholders in the Marico Biosphere Reserve: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned

Abstract

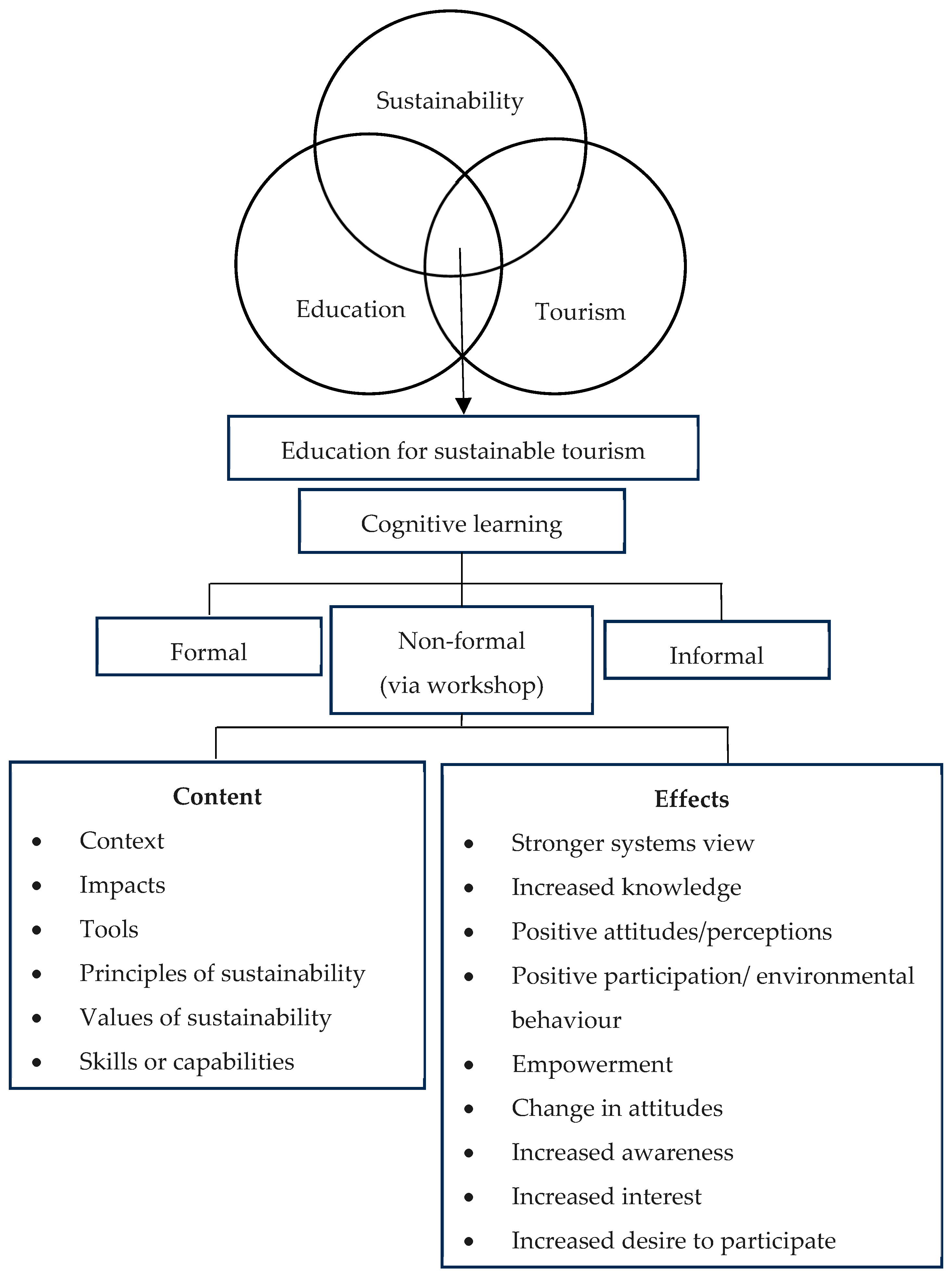

1. Introduction

2. Research Design and Methodology

2.1. Study Site, Population, and Sample

2.2. Workshop Design and Research Method

2.3. Data Analysis

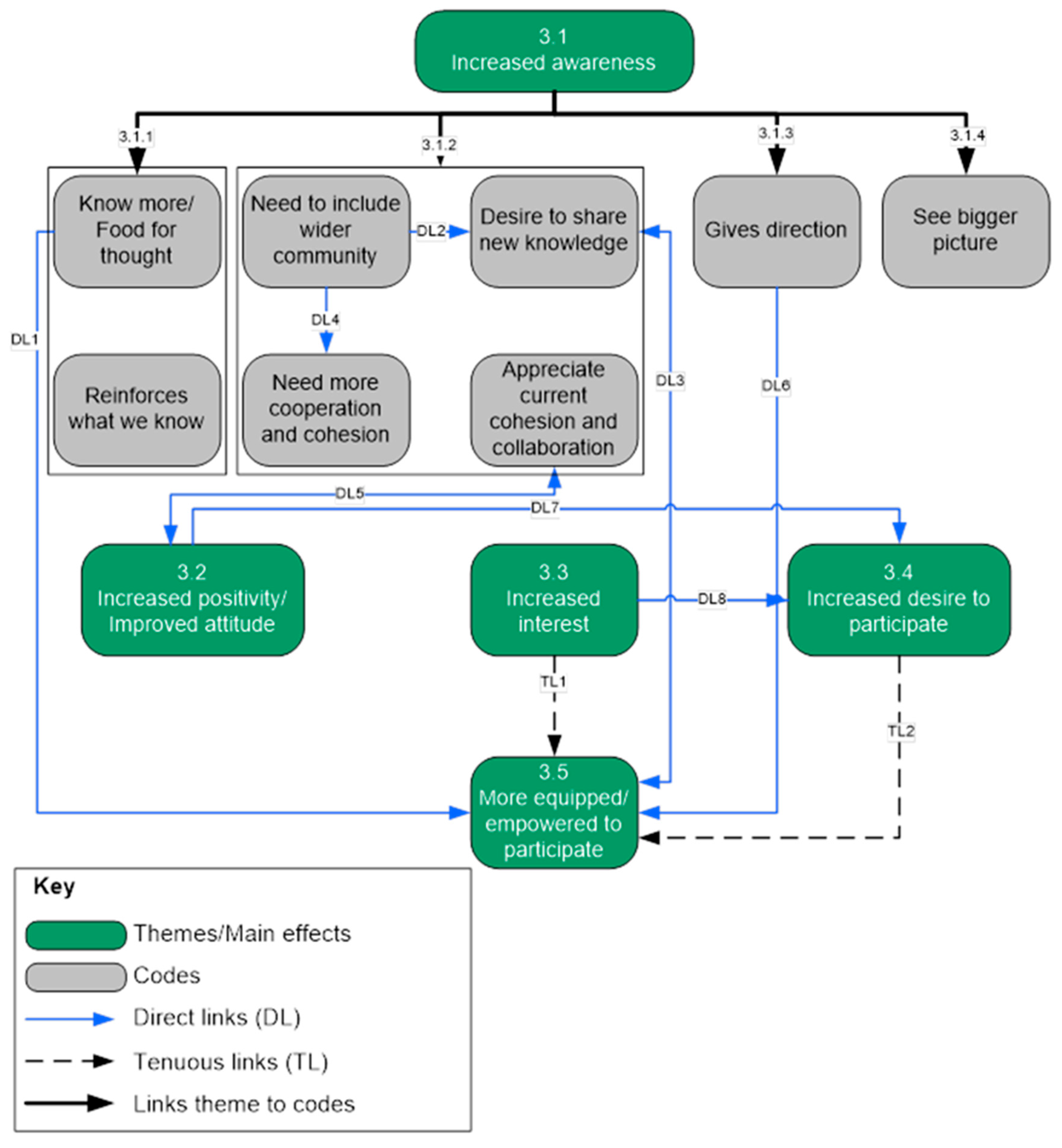

3. Findings and Discussion

3.1. Increased Awareness of Sustainable Tourism

3.1.1. Knowing More and Reinforcement

“I think we understand it better… than … in the beginning” (T2, P2).

“I think I’m more broad minded now. And I know things that I didn’t know before” (T2, P2).

“I definitely feel enlightened, I’ve got a broader knowledge base now to work with” (T2, P3).

“I have really learned a lot today” (T3, P2).

“… the fact that you included ‘The tourist’ as a fourth component of sustainable tourism has clarified a number of things and deepened the understanding. Because your normal literature … speaks about the environment and social and economic, but they don’t necessarily link the tourism, the tourist as a fourth component. … that was very valuable … because that’s the actual guy who must open his purse. It must be one of the components in our planning …” (T3, P3).

“[Sustainable tourism is] something we need to work on. … we’ve got the building blocks that we need to start working harder towards it, we need to understand more about it and how we can implement it in our daily lives here” (T2, P1).

“It’s a wonderful thing that we’ve been recognized for what we have here [referring to the biosphere designation] … as far as our nature is concerned. But we can obviously improve. And that’s what we’re trying to do in these types of workshops. We want to try and understand how we can improve things for the better, for everybody in the future” (T2, P1).

3.1.2. Community Participation, Knowledge Sharing, and Cohesion

“… after we’ve heard what you said here, [we need] younger people from Marico to participate, to buy-into what we are trying to achieve … they are the future, have the energy and are better with social media” (T1, P1).

“… that’s the only sad part of Marico … there’s no young blood coming, nothing … That’s the sustainable thing to work on …, bring younger people in …” (T1, P2).

“Yes … I have knowledgeable information after today, and I can try and evaluate it when I get home and try teach others on how to sustain the environment” (T2, P5).

“If you start telling people around you, it’s going to grow. … You need ambassadors for the biosphere … and more people will then become enlightened …. [We] can impart that knowledge to other people …” (T2, P3).

“[By] having these meetings we all walk away enlightened. So, you can … now … impart what we have. … Whereas before, I didn’t know much about it, so I didn’t know how to engage in conversation” (T2, P1).

“I also feel more motivated to see that there are more people involved … not that you are standing alone. … it’s very important that we should take hands and go forward” (T1, P1).

“Well, the networking is nice. You know which community members are on the same mindset, so, you can work together” (T2, P4).

“… to get cohesion in the group, that everyone is on the same chapter regarding what sustainability is …” (T3, P5).

3.1.3. Gives Direction

“… [the workshop] triggered … a way forward, with our emphasis on protecting our area” (T1, P1).

“I don’t think Marico gets enough tourists to have an impact yet, but it’s good to start now learning about it. If it becomes popular in the future—that we go in with the right mindset, that we don’t come back in ten years and say, ‘Oh, we should have done this …’. So, it’s good that you have told us, so we can’t say … we didn’t know” (T2, P4).

“… it gives us a direction … what to plan and how to do it” (T2, P1).

“… we can go and look for footpaths, develop walkways, the farmer’s wife could do a lunch … It could be … a whole new way of getting people involved. … if we can get a few more interesting places ready before December [holidays] … Let’s show them something new” (T3, P1).

“To make that practical, … as soon as possible, we must get together … and sort out the calendar for next year … and we must decide, this is our strategy and plan … to do something new for December … This workshop facilitated the process to get to that point” (T3, P5).

3.1.4. See Bigger Picture

“I thought as a young businessman, it’s only about making money, but after today [I have] a wider spectrum” (T1, P2).

“[There is] not only tourism, there’s the farming, there’s this and that … [which] become part of sustainability. … that’s the learning at the end of the day” (T2, P3).

“… I have gained a better understanding of how big the problem really is, how diverse it is, and in some ways, I feel more daunted … than I did before. I’m reminded of the idiom, ‘This is a big elephant, and how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time’. … how do I get the bite that’s going to matter the most within my capabilities? … So maybe some naivete has gone out … it’s a big and very complex issue” (T3, P4).

3.2. Increased Positivity/Improved Attitude Towards Sustainable Tourism

3.3. Increased Interest in Sustainable Tourism

3.4. Increased Desire to Participate in Sustainable Tourism

3.5. More Equipped/Empowered to Participate in Sustainable Tourism

“I like your idea of having more comprehensive information in each house about the environment … [for example] why we ask you to sort your rubbish … more of a code of conduct” (T1, P4).

“… the ideas or information you’ve given… has made me want to go back to my establishment, re-analyze … and … try to improve on certain things [to] give my guests a more … eco-friendly experience?” (T2, P1).

4. Conclusions and Lessons Learnt

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, A. Second-generation non-formal education and the sustainable development goals: Operationalising the SDGs through community learning centres. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2019, 38, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.A.L.; Ryan, L.D.; Davis, J.M. A deep dive into sustainability leadership through education for sustainability. In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse; English, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230514 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Shafiesabet, N.; Haratifard, S. The empowerment of local tourism stakeholders and their perceived environmental effects for participation in sustainable development of tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; van der Watt, H. Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ivlieva, O. Empowering communities to act for a change: A review of the community empowerment programs towards sustainability and resilience. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, D.; Malekpour, S.; Saeri, A.K.; Dargaveille, R. Rethinking community empowerment in the energy transformation: A critical review of the definitions, drivers and outcomes. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 72, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Marjoribanks, T.; Sullivan-Mort, G.; Manirujjaman, M.D.; Singaraju, S. Sustainability for ecotourism: Work identity and role of community capacity building. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Abooali, G.; Henderson, J. Community capacity building for tourism in a heritage village: The Case of Hawraman Takht in Iran. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. The Psychology of Intelligence; Routledge: London, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.; Morais, J. Non-formal education as a response to social problems in developing countries. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2024, 22, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Mohamadi, S.; Abbasi, A.; Dávid, L.D. Mapping a Sustainable and Responsible Tourism Paradigm: A Bibliometric and Citation Network Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme); UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers. 2005. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/making-tourism-more-sustainable-guide-policy-makers (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Petrisor, A.I.; Petre, R.; Meiţă, V. Difficulties in achieving social sustainability in a biosphere reserve. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 7, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sutawa, G.K. Issues on Bali tourism development and community empowerment to support sustainable tourism development. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agussalim, A.; Heriningsih, S.; Heriyanto, H. Local Community Participation in Sustainable Tourism Development in Sleman Regency: A Human Rights Approach. SHS Web Conf. 2025, 212, 04031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ramayah, T.; Hwang, J.; Kim, I. Community empowerment and sustainable tourism development: The mediating role of community support for tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, D.A.; Byrd, E.T.; Duffy, L.N. An exploratory study of community awareness of impacts and agreement to sustainable tourism development principles. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 15, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Designing powerful learning environments in education for sustainable development: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, G.M.; Lockstone-Binney, L.; Ong, F.; Wilson-Evered, E.; Blaer, M.; Whitelaw, P. Teaching sustainability in tourism education: A teaching simulation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfa, V.; Nugraheni, P.L. Effectiveness of community empowerment in waste management program to create sustainable tourism in Karawang, West Java. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 485, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; WU, H.C.; Wang, J.T.-M.; Wu, M.-R. Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1764–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Prideaux, B. Indigenous ecotourism in the Mayan rainforest of Palenque: Empowerment issues in sustainable development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Majewska, D. Formal, Non-Formal, and Informal Learning: What Are They, and How Can We Research Them? Cambridge University Press & Assessment: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- George, C.; Reed, M.G. Operationalising just sustainability: Towards a model for place-based governance. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1105–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. The importance of education for sustainability in tourism (Chapter 1). In Education for Sustainability in Tourism: A Handbook of Processes, Resources and Strategies; Moscardo, G., Benckendorff, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. What is qualitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 33, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, M.; Marvi, R.; Cuomo, M.T.; D’Amato, A. Sustainable Development Goals in a regional context: Conceptualising, measuring and managing residents’ perceptions. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2373871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayombe, C. Adult learners’ perception on the use of constructivist principles in teaching and learning in non-formal education centres in South Africa. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2020, 39, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomainen, S. Recognition and Student Perceptions of Non-Formal and Informal Learning of English for Specific Purposes in a University Context. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland, 2015. Available online: https://erepo.uef.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/1ce95436-2629-449c-83d9-e6b1f3a483c5/content (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO: Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB). Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/wnbr/about (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Rasoolimanesh, M.; Dorbeiki, M. Community-based model of tourism development in a biosphere reserve context. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Mammadova, A.; Smith, C.D.; Yashina, T. Comparative Analysis between the Role of Local Communities in Regional Development inside Japanese and Russian UNESCO’s Biosphere Reserves: Case Studies of Mount Hakusan and Katunskiy Biosphere Reserves. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marico Biosphere Reserve (Marico Biosphere Reserve Management Authority, Groot Marico, North-West, South Africa). Marico Biosphere Reserve: MAB UNESCO Application. Unpublished work. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Howell Major, C. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, G.R. Editor’s introduction: Focus group research. In Focus Group Research: Volume 1; Walden, G.R., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012; pp. xxvii–Ixx. [Google Scholar]

- Ørngreen, R.; Levinsen, K. Workshops as a research methodology. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2017, 15, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, L.; West, S.; Bourke, A.J.; d’Armengol, L.; Torrents, P.; Hardardottir, H.; Jansson, A.; Roldán, A.M. Learning to live with social-ecological complexity: An interpretive analysis of learning in 11 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. Educating destination communities for sustainability in tourism (Chapter 9). In Education for Sustainability in Tourism: A Handbook of Processes, Resources and Strategies; Moscardo, G., Benckendorff, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G.; Hughes, K. Rethinking interpretation to support sustainable tourist experiences in protected natural areas. J. Interpret. Res. 2023, 2, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business and Management, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, C.; Babin, B.; Carr, J.; Griffin, M.; Zikmund, W. Business Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, E. Stakeholder perceptions of sustainability and possible behaviour in a biosphere reserve. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 3843–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Kilic, H. Education for sustainable tourism development: An exploratory study of key learning factors. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejía, M.D.L.A.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, S.; Purwandari, S.A. Comprehensive micro, small, and medium enterprise empowerment model for developing sustainable tourism villages in rural communities: A perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workshop Content | Brief Explanation of Content |

|---|---|

| Biosphere reserves |

|

| Introducing sustainability |

|

| Introducing tourism |

|

| Introducing sustainable tourism |

|

| Understanding tourism impacts |

|

| Environment |

|

| Social |

|

| Economy |

|

| Tourist |

|

| Interpretation |

|

| Sustainable management |

|

| Case studies of sustainable tourism |

|

| Question | Effects of Sustainable Tourism Education on Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | How has your understanding of sustainable tourism changed after the workshop? |

|

| 2 | How did your opinions change about the Marico BR after the workshop? |

|

| 3 | After the workshop, are you more interested in the Marico BR? In what way? |

|

| 4 | After the workshop, how are you now equipped to contribute to or participate in sustainable tourism? |

|

| 5 | What will you now do as an individual to participate in sustainable tourism? |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Queiros, D.R.; Conradie, N.; Botha, E. Non-Formal Education on Sustainable Tourism for Local Stakeholders in the Marico Biosphere Reserve: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209138

Queiros DR, Conradie N, Botha E. Non-Formal Education on Sustainable Tourism for Local Stakeholders in the Marico Biosphere Reserve: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209138

Chicago/Turabian StyleQueiros, Dorothy Ruth, Nicolene Conradie, and Elricke Botha. 2025. "Non-Formal Education on Sustainable Tourism for Local Stakeholders in the Marico Biosphere Reserve: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209138

APA StyleQueiros, D. R., Conradie, N., & Botha, E. (2025). Non-Formal Education on Sustainable Tourism for Local Stakeholders in the Marico Biosphere Reserve: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned. Sustainability, 17(20), 9138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209138