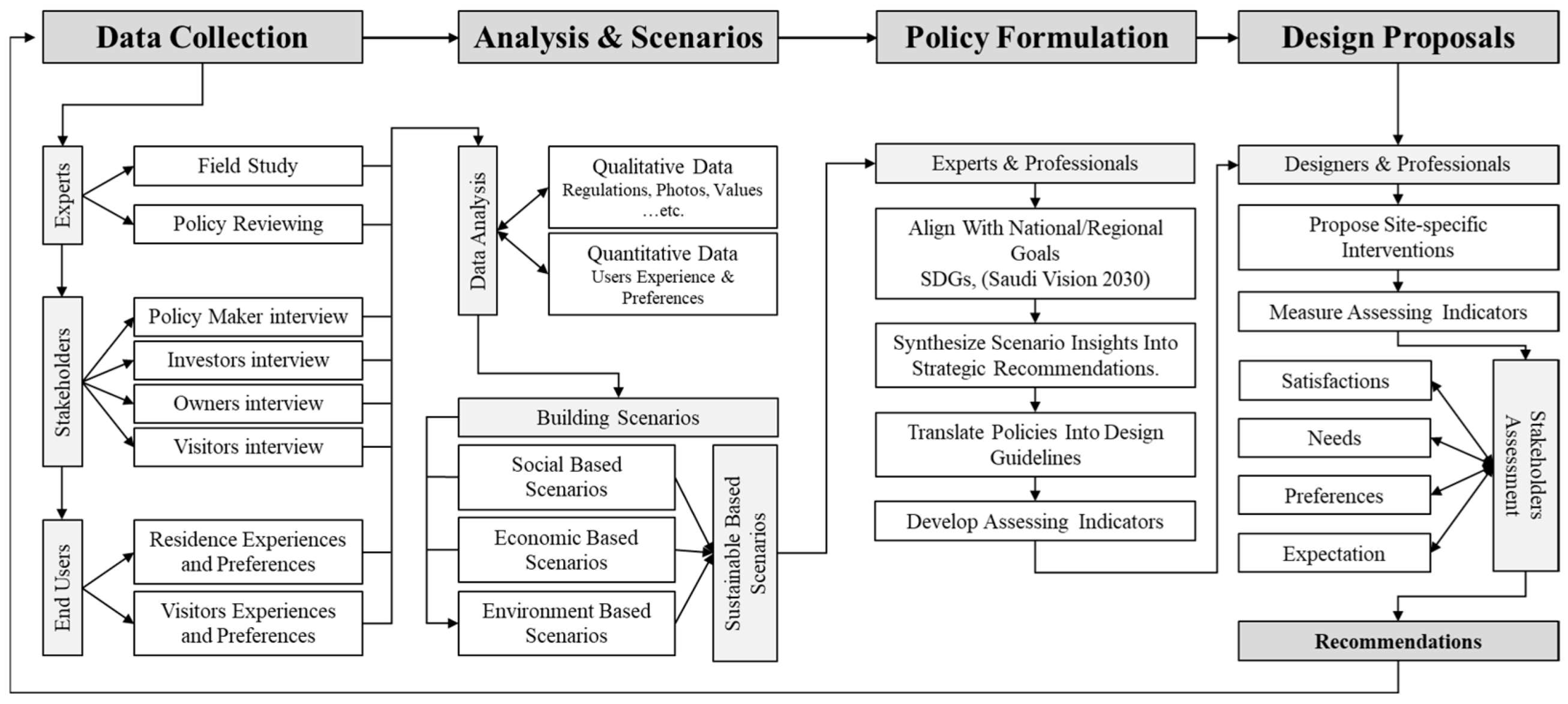

The Humanizing Sustainable Corridors Framework (HSCF) is grounded in a structured conceptual framework and guided by systematic data analysis. The three stages of data collection were analyzed using appropriate qualitative and quantitative methods to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter, as well as the validity and reliability of the findings. The following sections present and interpret the results from each stage of the data collection process.

5.1.1. Data Analysis of Expert Observations and Regulatory Review

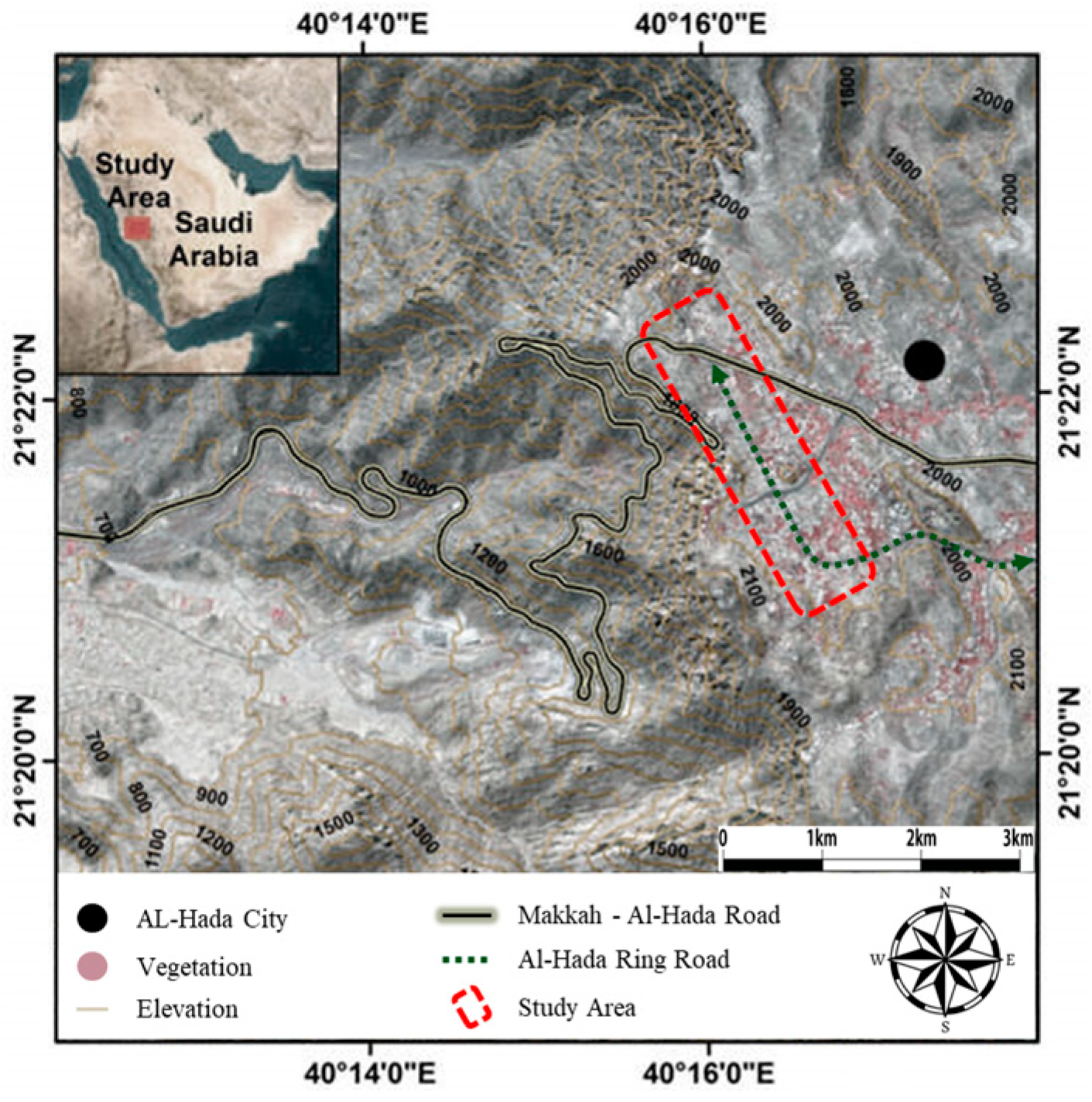

To initiate the empirical assessment of the Al-Hada Ring Road corridor, a specialized Expert Observation Group was established, comprising urban planners, architects, transportation engineers, environmental analysts, and heritage conservation professionals. Before conducting the site visit, the experts held focus group discussions with representatives from the Municipality of Taif, the Ministry of Tourism, and other key agencies to gain an understanding of the institutional objectives, development priorities, and long-term visions for the area. These discussions provided critical insights into why the corridor was identified as a strategic development zone and clarified the policy gaps and investment aspirations shaping the proposed interventions.

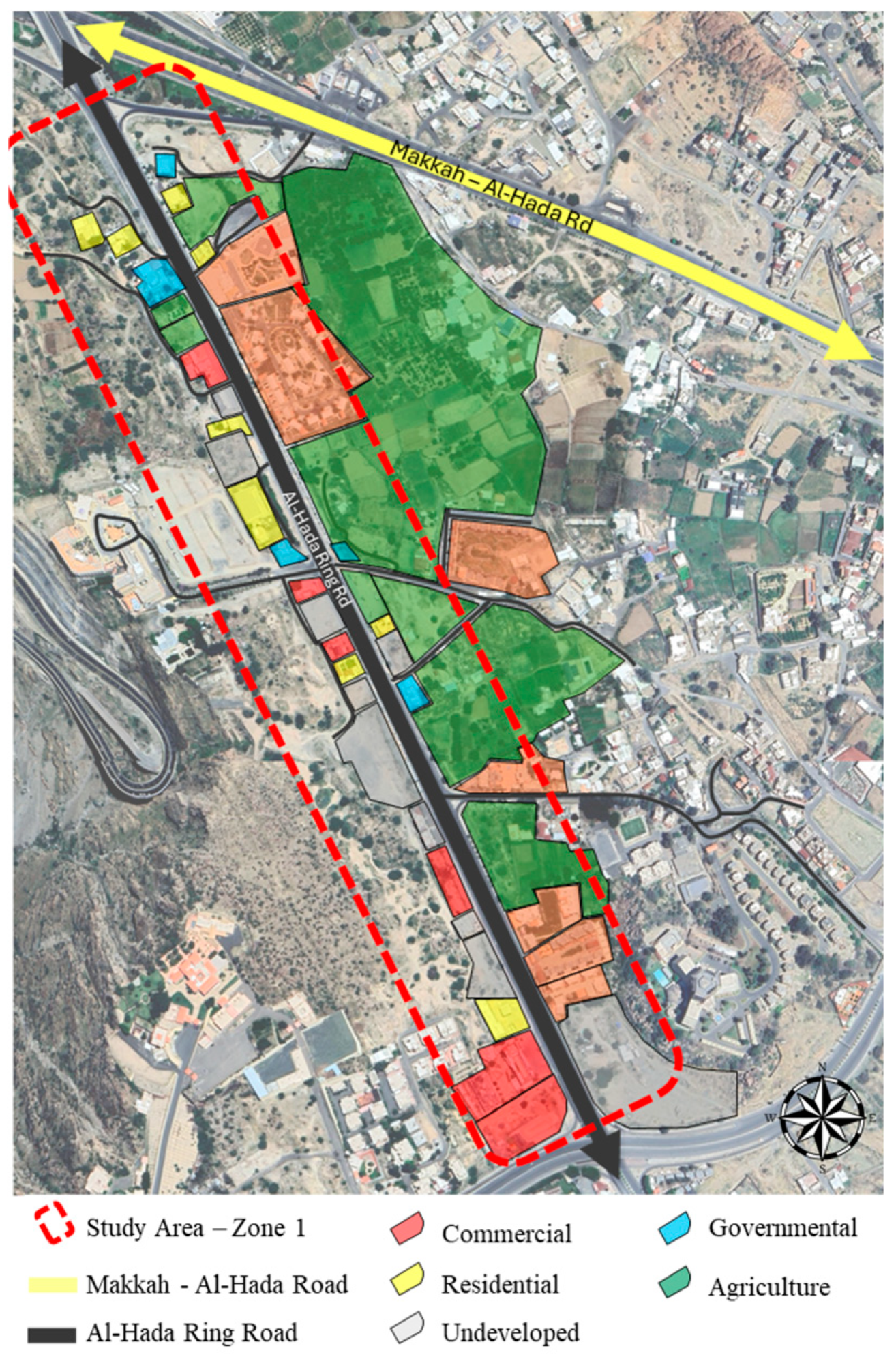

Following the institutional engagement, the team prepared standardized observation protocols and spatial mapping templates using Google Maps to enable a systematic analysis of base maps in comparison with the existing on-site conditions through a SWOT analysis. Prior to the field visit, the experts also reviewed planning regulations, official land use maps, and high-resolution satellite imagery provided by municipal consultants during the focus group meetings. This preparatory phase ensured that the site visit was both evidence-driven and aligned with the development objectives articulated by local authorities and tourism agencies.

Upon arrival at the study area, the experts systematically traversed the entire corridor using vehicular and pedestrian modes to document existing conditions through geotagged photographs, sketch mapping, and structured field notes. The observations encompassed land use distribution, walkability conditions, mobility infrastructure, heritage sites, environmental assets, and informal activities such as food vending and recreational gatherings. Using the SWOT framework, the findings were categorized to identify the strengths (e.g., natural landscapes, heritage assets), weaknesses (e.g., lack of pedestrian facilities, absence of signage), opportunities (e.g., eco-tourism potential, cultural branding), and threats (e.g., safety hazards, unregulated construction) shaping the development trajectory of the corridor, as illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

This integrated methodological approach, beginning with institutional consultation and followed by empirical fieldwork, provided a comprehensive, multi-dimensional understanding of spatial, social, and regulatory challenges. It ensured that subsequent stakeholder engagement and planning proposals were firmly grounded in both policy perspectives and evidence-based field assessments, thereby enhancing the validity, transferability, and replicability of the research framework for similar urban corridors in arid and tourism-sensitive regions.

The outcomes of the site visits are summarized in

Table 6, which presents the key findings from field observations along the Al-Hada Ring Road corridor. These observations assessed the existing condition and highlighted a range of spatial and functional challenges that impact the quality, safety, and identity of the corridor.

As shown in

Figure 7, one of the most prominent issues is the informal use of pedestrian sidewalks for activities such as sitting, cooking, barbecuing, and camping, suggesting a lack of designated public gathering spaces that accommodate visitors’ social needs.

The area also demonstrates inconsistent and overlapping land uses, where agricultural, commercial, and residential functions coexist without a unified zoning code or coordinated development guidelines. This lack of planning control has led to the unregulated transformation of agricultural lands into concrete tourism-oriented structures, which significantly undermines the rural and environmental character of the area.

Another major concern is the high vehicular speed (90–100 km/h) along the corridor, which is incompatible with areas of informal pedestrian activity and raises serious safety risks. The presence of informal food trucks and vendors contributes to visual clutter and unmanaged use of public space. Additionally, the absence of wayfinding signage and clear directional systems makes navigation difficult, especially for first-time visitors. I found that there is a shortage of basic infrastructure, such as public toilets, shaded seating areas, and proper sidewalks, which reduces the efficiency of the space, especially for families and groups.

The area attracts many pedestrians and cyclists during the peak seasons, and it suffers from proper sidewalks and bike lanes, which puts users at risk by forcing them to share the road with vehicles. Regarding architectural identity, the new buildings lack architectural identity and heritage because of the absence of building codes and regulations. The experts also revealed that the lack of public transportation modes makes users rely on private cars for transportation.

Regarding the environment, the experts highlight that the historical heritage areas and landmarks were overlooked. The natural areas are underutilized, representing missed opportunities for economic, cultural, tourism, agricultural, and sustainable development. They found that Al-Hada Ring Road remains economically underdeveloped, and it suffers from the lack of strategic planning and formal investment structures. These findings provide a clear picture of the current condition of Al-Hada Ring Road and highlight the urgent need for planning solutions.

Building on the initial site visit, where numerous regulatory and planning questions emerged regarding informal construction practices, overlooked heritage areas, and underutilized natural assets, the expert team proceeded to a second phase of inquiry involving focus group discussions with relevant government agencies. This transition was essential to move from empirical observations to a deeper understanding of the institutional and regulatory frameworks shaping the Al-Hada Ring Road corridor. By engaging municipal authorities, planning departments, and tourism agencies, the experts sought clarification on the existence of formal development visions, regulatory instruments, and enforcement mechanisms governing land use, building codes, and strategic planning efforts. This step ensured that the environmental, cultural, and economic issues identified during the site visit were critically examined in the context of existing policies and institutional responsibilities, thereby creating a comprehensive basis for evaluating the corridor’s developmental trajectory.

This assessment encompassed land use and land ownership analysis, building codes, and development guidelines, including a critical examination of ownership patterns. The regulatory framework was further examined through a series of focus groups and workshops, where representatives from key governmental bodies presented the regulations governing development in the area. For example, the Municipality of Taif provided the official land use map, building height regulations, and setback requirements for different zones. These regulations were subsequently discussed and critically evaluated during the focus group and workshop sessions to ensure a comprehensive understanding of their implications for future urban development.

The adoption of the expert site visit was particularly appropriate given its capacity to capture specialized, context-specific insights that are often unattainable through general surveys or secondary data sources. Engaging experts such as urban planners, architects, policymakers, and sustainability practitioners provided access to both technical knowledge and practical experience necessary to evaluate complex parameters, including spatial integration, cultural identity, and environmental responsiveness. Their informed perspectives ensured that assessments were grounded in professional judgment rather than subjective impressions. Moreover, expert surveys facilitated timely and focused data collection, reducing interpretive ambiguities while complementing user-based surveys. This integrated approach enhanced the framework’s robustness, ensuring that the proposed design strategies were firmly aligned with both theoretical foundations and professional practice imperatives.

After assessing the existing condition, structured workshops were held with different stakeholders, including agencies from Taif Municipality (Planning and Investment Departments), the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Tourism, private investors, and planning professionals. These workshops validate the field findings, reveal policy gaps, and clarify institutional priorities and visions. By combining both findings of the site visit and interpreting them with reviewing the regulations, several issues were identified, including fragmented land ownership that blocks large-scale development, outdated zoning that does not reflect current uses, weak coordination between agencies, and a lack of infrastructure to support tourism growth.

According to the stakeholders’ visions, Taif Municipality expressed interest in turning government-managed areas into income-generating spaces. The Ministry of Culture emphasized the importance of heritage preservation, while the Ministry of Tourism promoted rural tourism, eco-lodging, and private sector participation. All agencies are looking forward to sustainable income as a main goal that planners and designers must consider for drawing development plans.

Therefore, the expert team used a SWOT analysis to categorize the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to both spatial conditions and institutional frameworks (

Table 7). This helped assess the corridor’s potential and the barriers that must be addressed to guide sustainable development [

34].

The key strengths identified included the natural landscapes and scenic viewpoints, government interest in sustainable investment, the presence of cultural and heritage assets, and good weather. Weaknesses included the lack of a unified land use code, inadequate infrastructure, the absence of public transportation, and the neglect of heritage areas. Opportunities emerged in the form of eco-tourism, heritage branding, the use of local materials, and increased stakeholder alignment. However, several threats were also identified, including flash floods, traffic-related safety risks, legal challenges from fragmented land ownership, and the potential exclusion of rural communities from the benefits of future development.

In conclusion, this stage revealed the complex socio-spatial behavior and the influence of regulations that shape Al-Hada Ring Road. It emphasized the importance of combining field assessments with institutional perspectives to develop context-sensitive, feasible, and inclusive planning solutions. These findings are the basis for the next stages of data collection, including stakeholders’ interviews and a web-based questionnaire, which will be used for triangulated and generalized data for future development.

5.1.3. Data Analysis of Web-Based Questionnaire

The analysis of the web-based questionnaire represents a pivotal component of the Humanizing Sustainable Corridors Framework (HSCF), serving to validate and generalize the qualitative findings from expert observations and stakeholder interviews. A total of 455 valid responses were collected, forming a statistically robust sample for exploratory descriptive analysis. Data was processed using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS (Version 21), focusing primarily on frequency distributions due to the multiple-answer structure of most survey questions (

Table 9).

The demographic analysis showed that 87.5% of the respondents were male, where males are more likely to use public open spaces. This pattern is influenced by cultural norms and also by the fact that the survey team consisted only of male researchers, which may have limited female participation. The majority of participants were aged 31–50 years (64.6%), which is the age group most active in work and social life. They are also often responsible for family activities and mobility. This agrees with the findings from expert field observations that were conducted in the first stage, which highlight that middle-aged adults play a key role in shaping outdoor activities. They were also more likely to participate in the online survey, as they generally have greater access to web-based tools compared to older adults who may face challenges in using digital platforms and younger individuals, who may lack the resources or interest to engage in such activities.

Most respondents (76.04%) were married, and 58.5% reported visiting the corridor with family, confirming the corridor’s use as a family-oriented public space. This supports Carmona’s (2021) suggestion that well-designed corridors should be inclusive and support group-based activities [

2]. In terms of user type, 84% were visitors, while only 13% were landowners and 3% were investors. This indicates that the Al-Hada corridor is mostly used for temporary recreation rather than permanent living or business. Moreover, 44.2% of the sample had monthly incomes above SAR 10,000, suggesting that many users may have higher expectations for services, comfort, and design quality, as seen in other high-income urban user groups.

Geographically, most responses came from Makkah (65.7%), followed by Jeddah (14.3%) and Taif (7%), showing that the Al-Hada Ring Road is an important regional destination. These patterns support the idea that the corridor plays a key role as a recreational and social space for nearby urban populations. They also highlight the need to improve natural, clean, and accessible environments that respond to the needs of middle-aged, family-oriented, and urban-based users’ goals that are strongly aligned with the Saudi Vision 2030 agenda for vibrant and livable cities [

1,

19].

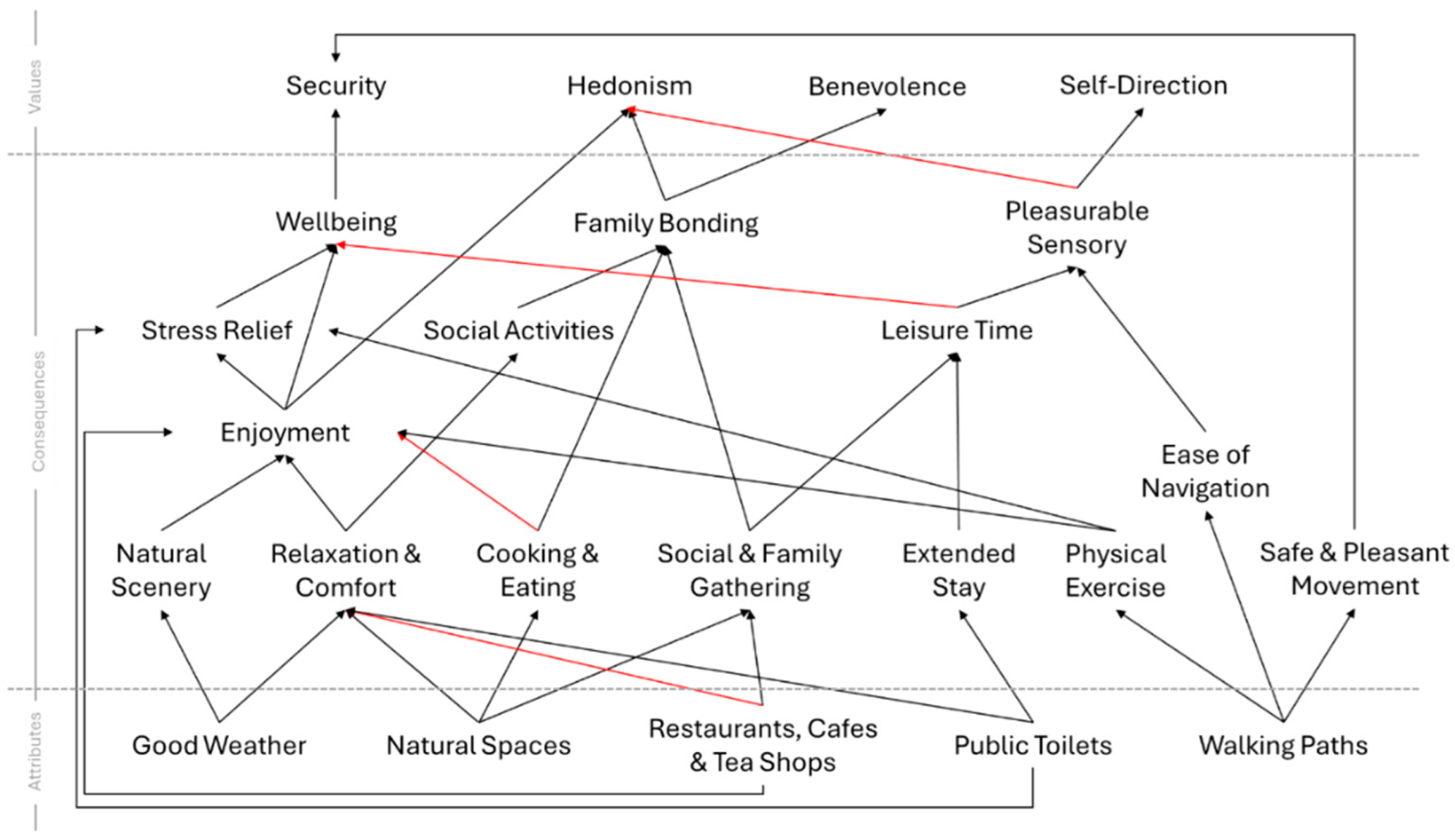

Figure 10 illustrates the most frequently selected motivational urban attributes, where good weather (93.8%), natural recreational spaces (66.8%), and cafes and tea shops (59.8%) were the most frequently selected responses. These results are consistent with expert observations of high activity concentrations in shaded natural areas and near informal gathering spots like roadside cafés and tea stands. Stakeholders, including local entrepreneurs and service providers, emphasized that the climate and access to leisure amenities were central to attracting visitors, especially on weekends and holidays.

The inclusion of multiple response options was crucial here, as visitors’ motivations were not singular. The tendency to value combinations of comfort, food, and natural ambiance aligns with the Means–End Chain (MEC) analysis from the interviews, where such attributes were linked to emotional and functional benefits like stress relief, social bonding, and hedonic satisfaction.

In regard to the preferred urban attributes,

Table 10 presents the frequency and percentage of responses identifying preferred urban attributes, grouped into four major categories: availability of amenities, availability of infrastructure, accessibility, and environmental quality. These categories were derived based on the theoretical framework and stakeholder input developed in previous research phases (see

Section 3). The questionnaire allowed for multiple answers, thus responses reflect collective preferences rather than exclusive choices.

As shown in

Table 10, the evaluation order follows a logical progression from the most immediate and tangible urban needs toward broader environmental considerations. First, the availability of amenities reflects the direct functional and social elements that influence users’ daily experiences, such as recreational, commercial, and cultural facilities. Second, the availability of infrastructure captures the physical and technical systems that enable basic urban functionality and convenience. Third, accessibility addresses the spatial and mobility dimensions that facilitate users’ movement and interaction across urban areas. Finally, environmental quality emphasizes the broader ecological and climatic factors contributing to long-term livability and sustainability.

This structured approach ensures that respondents’ preferences are analyzed across layers of urban experience, progressing from individual-level necessities to collective environmental benefits.

The availability of amenities attributes received the highest concentration of responses. The most frequently selected attribute was natural areas, parks, picnic areas, camping areas, and hiking areas (79.3%), followed by cafes and tea shops (59.8%) and kids’ playgrounds and gardens (58%). This indicates a strong public preference for nature-based, leisure-oriented environments, consistent with a growing body of research that highlights the restorative, social, and cultural value of green and open spaces in urban settings [

4,

47]. Additionally, the attributes such as free seating areas (45.3%) and heritage areas (34.1%) underscore the importance of comfort and cultural continuity in the design of public spaces. The lower frequencies for health facilities (19.1%), horse and ATV tracks (18.2%), and hotels and resorts (7.3%) suggest that while visitors appreciate recreational and heritage amenities, these are secondary to more casual and accessible features. Only 1.1% selected police and security stations, possibly reflecting implicit assumptions of general safety or a lower perceived value of visible security infrastructure during leisure activities.

The second category, availability of infrastructure, received moderate preference levels. Public toilets were most cited (43.5%), followed by sidewalks (31.2%) and parking (20.4%), highlighting the importance of basic mobility and hygiene services. Lower preferences for lighting, cell coverage, and road conditions suggest that digital and vehicular infrastructure are less prioritized. This may be due to their existing availability, making them less noticeable to respondents, or because most visits are short and centered on leisure and nature, reducing the perceived need for extensive infrastructure upgrades. The relatively low selection of bike lanes (1.3%) and bus stops (0.9%) may indicate a gap in the integration of alternative transportation modes or a cultural preference for private vehicles, consistent with regional mobility behavior.

Accessibility attributes received relatively low emphasis overall, with spatial proximity (37.6%) rated highest, followed by convenient access (16.0%). These findings are consistent with expert observations and stakeholder interviews, which have highlighted that most visitors rely on private vehicles and prefer destinations that are easy to reach without the need for complex transport systems. The very low preference for alternative transportation modes (1.5%) reinforces this behavior, reflecting limited use of public transit and a cultural reliance on direct, car-based access. As such, proximity remains more critical than the availability of transport infrastructure, particularly for short, leisure-focused visits.

Environmental Quality attributes were among the most influential factors in visitors’ preferences. Good weather was the most cited individual attribute across the entire dataset (95.4%), highlighting the essential role of climate comfort in shaping outdoor activities, particularly in arid and hot regions like western Saudi Arabia. Tranquility followed at 37.8%, emphasizing the value of quiet and peaceful environments that support emotional and psychological well-being. While attributes such as safety and security (16.7%), cleanliness (12.5%), affordability (8.1%), and quality of services (6.6%) received lower percentages, this may not indicate a lack of importance but rather a perception of their adequacy respondents may consider these elements to be already acceptable or available, and thus less in need of attention. Overall, the findings suggest that visitors primarily seek to enjoy the natural setting and favorable weather in a calm, undisturbed atmosphere, where tranquility and comfort take precedence over economic or service-based concerns.

The strong preference for natural and comfortable urban attributes identified in the survey results highlights a critical need for integrated green infrastructure and accessible, low-impact amenities in urban planning, particularly for tourism and public engagement. These findings support and expand upon earlier insights from stakeholder interviews and expert observations, which emphasized environmental integration, walkability, and social cohesion as central to transforming urban corridors such as the Al-Hada Ring Road. The dominant respondent group, middle-aged users, demonstrated a clear interest in outdoor experiences that combine cultural connection, relaxation, and scenic quality. Importantly, the data reveal that users are not looking for high-tech or heavily urbanized interventions; rather, they are drawn to the simplicity and emotional value of natural landscapes, fresh air, and favorable weather conditions, evidenced by the 95.4% citation of good weather as a key motivation. As such, the design implications are clear: future interventions should avoid disruptive or technologically intensive development and instead adopt a nature-sensitive approach that preserves native vegetation, respects existing topography, and enhances microclimatic comfort. These user-driven preferences directly influence the kinds of activities visitors are most likely to enjoy, which are explored in the following section.

The final section of the web-based questionnaire was designed to identify the types of activities visitors most commonly engage in while visiting the Al-Hada Ring Road. The responses reflect a clear preference for informal, nature-based, and socially inclusive experiences, consistent with the environmental and spatial preferences discussed in the previous sections.

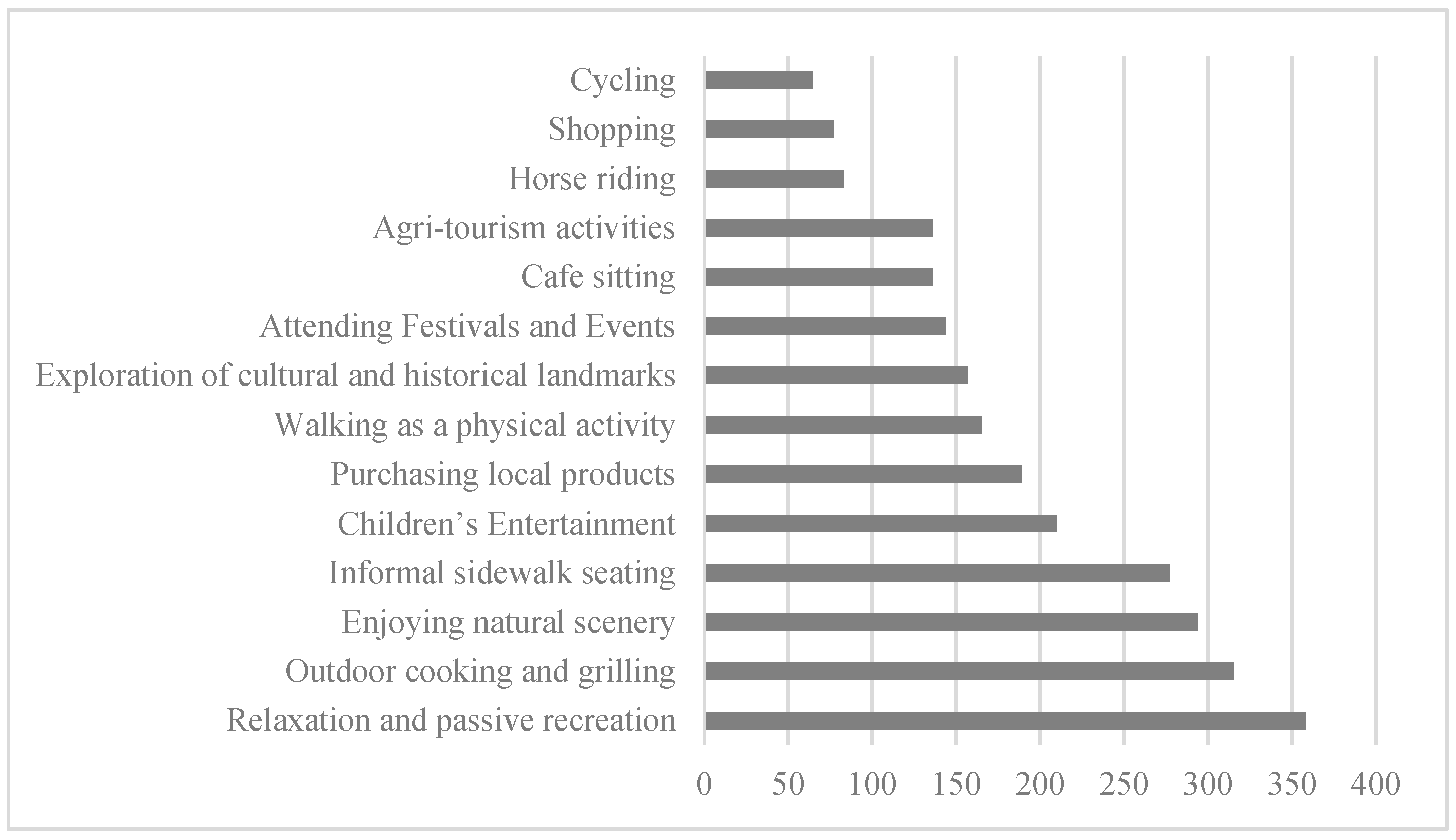

As summarized in

Figure 10, the most commonly reported activities were relaxation and passive recreation (78.7%), followed closely by outdoor cooking and grilling (69.2%) and enjoying natural scenery (64.6%). These activities require minimal infrastructure but high environmental quality, reinforcing the earlier conclusion that users value climate comfort, tranquility, and access to green open spaces over built or commercialized interventions. Similarly, informal sidewalk seating (60.9%) and children’s entertainment (46.2%) further support the importance of family-friendly, comfortable, and sociable spaces.

The findings also reveal that many visitors are interested in engaging with local culture and economy, as reflected by preferences for purchasing local products (41.5%) and exploring cultural and historical landmarks (34.5%). These results suggest that visitors are not only motivated by nature and comfort but also seek authentic cultural engagement, aligning with national goals to promote heritage tourism and community-based economic development, as outlined in Saudi Vision 2030 [

19].

While lower in frequency, activities such as agri-tourism (29.9%), café sitting (29.9%), horse riding (18.2%), shopping (16.9%), and cycling (14.3%) represent emerging or underdeveloped opportunities. These could be enhanced through strategic planning and infrastructure improvements that maintain the natural and cultural character of the corridor. However, any future development must be carefully balanced to preserve the area’s environmental sensitivity and its appeal as a peaceful retreat, as emphasized by earlier expert observations and stakeholder interviews.

Overall, the activity preferences demonstrate that users are drawn to the corridor for a blend of restorative, recreational, and culturally immersive experiences. This supports the broader conclusion that planning for such spaces should prioritize low-impact, ecologically integrated, and community-aligned design interventions, providing visitors with meaningful yet sustainable ways to engage with the landscape.