1. Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, the sharp rise in carbon emissions from human activities has become the main driver of global warming. This has resulted in more frequent extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and other serious challenges, posing systemic threats to global economic and social development [

1]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Seventh Assessment Report (AR7) confirms that climate change is now affecting every region of human habitation. Extreme events such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and droughts occur worldwide, while existing models still struggle to capture the rapid pace of climate change. With the signing of the Paris Agreement and China’s global commitment to “peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and strive for carbon neutrality before 2060” (hereinafter referred to as the “Dual Carbon” Goals), enterprises face intensifying climate-related risks and transition pressures [

2]. Against this backdrop, “carbon risk” has gradually become a core topic in corporate strategy and financial performance research. It primarily refers to compliance costs, stranded asset risks, and competitive uncertainties confronting enterprises due to tighter climate policies, technological shifts, and evolving market preferences for low-carbon models [

3]. Specifically, as the economy and society pursue low-carbon transition, costs stemming from corporate carbon emissions are increasingly internalized. Carbon risk not only directly raises enterprises’ operating and compliance costs [

4] but also elevates their financing thresholds and capital costs, creating financial risks [

5]. Under such pressures, enterprises must urgently sustain their growth and market standing through environmental management and social responsibility fulfillment to enhance corporate value. Carbon risk encompasses multiple factors that pose latent risks to corporate operations, particularly for high-carbon-emission enterprises. These enterprises must not only navigate stricter carbon emission policies but also adapt to shifting market preferences for low-carbon products and technological disruptions. Thus, carbon risk has become a pivotal factor shaping the value creation of high-carbon-emission enterprises.

Existing literature on carbon risk can be roughly divided into two perspectives: one emphasizes the compliance and operational costs it entails, arguing that carbon regulations increase corporate burdens and reduce short-term financial performance [

6]; the other points out that effective carbon risk management can trigger an innovation compensation effect, enhancing enterprises’ long-term competitiveness through green technological innovation and efficiency improvement [

7]. However, most existing studies focus on developed country markets or remain limited to evaluating effects at the macro-policy and industry levels. They lack systematic examination of firm-level micro-mechanisms—especially the transmission paths between carbon risk and corporate value under different ownership structures and scale characteristics [

8]. Additionally, although carbon risk is a global phenomenon, its manifestations and impact mechanisms may vary significantly across economies with distinctly different institutional backgrounds. As the world’s largest carbon emitter and a representative emerging market, China’s advancement of the “Dual Carbon” goals provides a unique policy laboratory for corporate carbon risk management [

9]. Focusing on Chinese high carbon-emission industries is therefore not only of local policy significance but also provides a valuable comparative case for understanding national climate governance and corporate responses.

Based on the aforementioned research gaps, this study uses listed companies in high-carbon-emission industries on China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-shares from 2012 to 2022 as the sample. It constructs a carbon risk measurement index based on industrial energy consumption and employs regression analysis to explore in depth the relationship between carbon risk and the value of high-carbon-emission enterprises, as well as the underlying mechanisms. It also aims to expand theories related to environmental regulation and corporate value—particularly from the perspective of the Resource-Based View [

10] and Institutional Theory [

11]—to reveal the “double-edged sword” effect of carbon risk in a specific institutional context.

The potential contributions of this study are reflected in three aspects: First, it uncovers the dual mechanisms through which carbon risk influences firm value at the micro level, addressing the gap in prior research that emphasizes macro perspectives while overlooking micro-level heterogeneity. Second, it analyzes differences between state-owned and private firms, as well as between large and small firms in China, providing evidence to support the design of more targeted climate policies. Third, it identifies the value relevance of carbon risk and offers empirical evidence for firms to refine low-carbon strategies, for investors to strengthen ESG evaluation, and for policymakers to improve carbon market mechanisms. Overall, the research findings not only help understand how high-carbon-emission enterprises can achieve sustainable value creation under the “Dual Carbon” Goals but also provide insights for emerging economies worldwide to balance economic growth and climate governance.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

Carbon risk, a prominent corporate risk dimension under climate change, refers to compliance costs, stranded asset risks, and uncertainties in the operating environment arising from stricter climate policies, technological change, and shifting market preferences [

3]. Prior research shows that carbon risk affects not only financial performance but also value creation through multiple channels, particularly in high carbon-emission industries. Yet, its overall impact remains debated. Some studies emphasize rising costs and reduced investment [

6], whereas others suggest potential innovation compensation effects that strengthen long-term competitiveness [

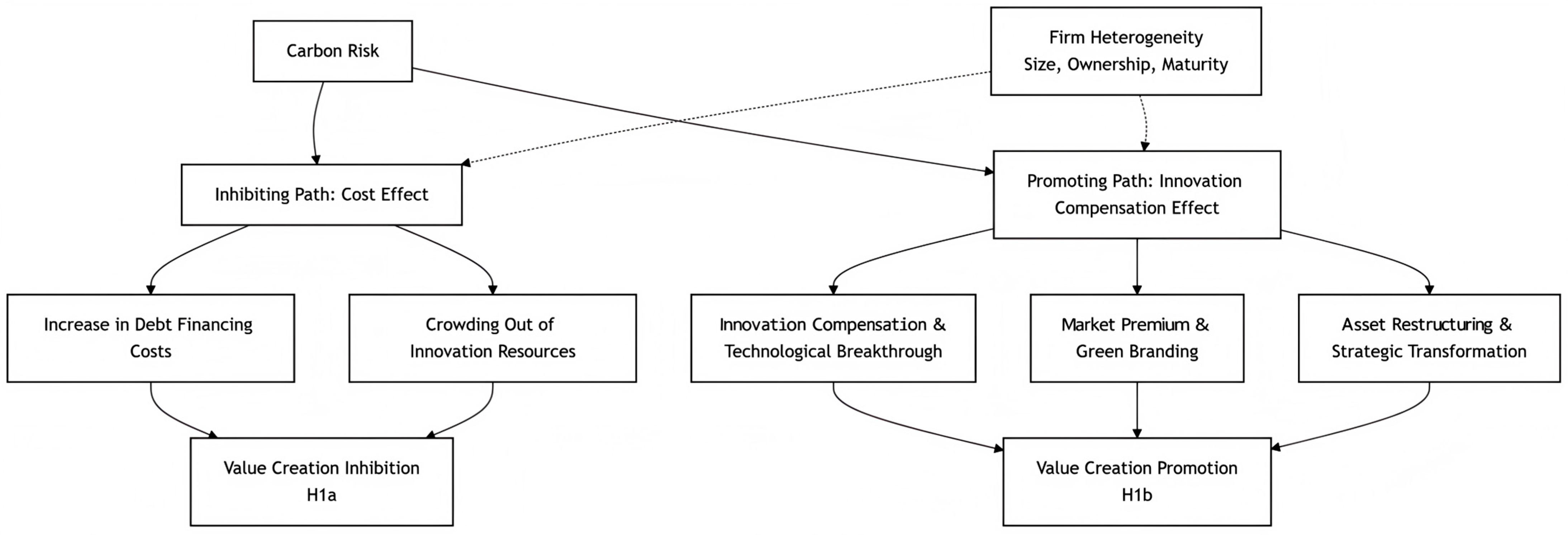

7]. Based on this, this study constructs a dual-path theoretical framework (

Figure 1) to systematically explain how carbon risk influences corporate value creation through the “cost effect” and “innovation compensation effect,” and proposes competing hypotheses.

First, carbon risk constrains enterprises’ value creation capabilities by increasing debt financing costs. Based on agency theory, there exists a conflict of interest between enterprises and creditors amid carbon risk: enterprises may tend to invest in high-carbon projects to pursue short-term profits, while creditors focus on the threat of long-term environmental risks to debt-servicing capacity [

47]. This agency conflict leads creditors to demand a higher risk premium from high-carbon enterprises. Specifically, first, according to the Cost Theory, carbon risk raises enterprises’ debt financing costs. Against the backdrop of strengthened carbon regulations (e.g., carbon taxes, carbon emission trading systems), creditors pay greater attention to enterprises’ carbon exposure levels. Studies show that the loan spreads of carbon-intensive enterprises increase significantly as climate policies become stricter. Particularly in China, green credit policies require financial institutions to incorporate carbon information into credit decisions, and the quality of carbon information disclosure is significantly negatively correlated with debt financing costs. If enterprises fail to manage carbon risk effectively, they will face exacerbated financing constraints and rising interest rates. Further, high corporate debt financing costs may hinder value creation. Debt financing elevates a company’s financing costs owing to fixed interest payments. Substantial interest costs constrain corporate cash flow, curtailing reinvestment capacity and consequently suppressing value creation. Additionally, excessive borrowing costs generate investor uncertainty regarding debt repayment capacity, triggering stock price declines and eroding market confidence. This vicious cycle exacerbates financing costs while continuously suppressing value creation.

Second, carbon risk may constrain corporate value creation through increased R&D investment requirements in innovation. Carbon risks originate primarily from exogenous factors, particularly regulatory and policy changes. These external pressures compel firms to allocate additional R&D investment toward innovation. Governments impose carbon emission costs via taxation or trading schemes, mandating firms to pursue emission reduction through technological innovation while complying with stringent standards that necessitate process improvements or low-carbon technology development [

7]. The implementation of carbon reduction policies directly increases compliance costs for high-emission companies. Carbon risks necessitate strategic re-evaluation of development models, thereby stimulating internal R&D expenditures. The development of low-carbon technologies enables firms to diminish reliance on high-emission operations while hedging against policy change risks. Low-carbon technologies potentially reduce energy consumption and emission costs, thus decreasing long-term operational expenditures. Consequently, firms must prioritize investments in energy-efficient technologies, carbon allowances, tax obligations, and emission-related R&D to bolster innovation capabilities. Furthermore, resource-constrained firms face crowding-out effects as carbon-reduction investments compete with production, operations, and other innovation funding, ultimately impairing operational efficiency. At the same time, the inherent uncertainty of R&D outcomes may result in non-productive investments, undermining value creation. Additionally, environmental equipment installation incurs learning costs that reallocate human resources from production and R&D activities [

48]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis H1a:

H1a. Carbon risk exerts a significant negative impact on the value creation of high-carbon-emission enterprises.

According to Porter’s hypothesis, environmental regulation generates three key effects—first-mover advantage, innovation compensation, and learning effects—all of which contribute to increased enterprise value [

7]. For high-carbon-emitting enterprises, carbon risk, as a form of environmental regulatory pressure, can enhance value creation through three distinct pathways:

First, the innovative compensation path. Against the backdrop of the gradual strengthening of carbon constraint policies, the innovation compensation effect emerges as the primary approach for high-carbon-emitting enterprises to manage carbon risk. When policy pressure exhibits a progressive nature, firms can achieve value enhancement through systematic innovation activities. Specifically, companies will augment their R&D investment in low-carbon technologies, encompassing the development of breakthrough technologies like carbon capture and storage (CCUS) technology and the hydrogen smelting process, as well as incremental innovations such as waste heat recovery and energy efficiency enhancement. Such technological innovations not only yield direct cost savings but, more importantly, create green technology barriers that are difficult to replicate. It is noteworthy that substantial industry heterogeneity exists in the innovation compensation effect, and this path holds particular significance in technology-intensive industries. Enterprises in these industries establish a green intellectual property system through patent portfolios, thereby securing new types of value sources, such as technology licensing revenues.

Second, the market premium path. As consumers’ environmental awareness awakens and green consumption preferences take shape, the path of transforming carbon risks into market opportunities has gained increasing significance. This path primarily creates value through three mechanisms: the green brand premium effect, the green supply chain access advantage, and the green financing convenience. It should be emphasized that export-oriented enterprises derive more substantial benefits from this path. Moreover, the effectiveness of the market premium path hinges on enterprises’ signalling capabilities. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to enhance carbon information disclosure and third-party verification.

Third, the asset replacement path. When the structural transformation of energy prices surpasses the tipping point, the asset replacement path serves as the core channel for the transformation of high-carbon enterprises. This path manifests itself in two levels of strategic adjustment: with regard to stock assets, enterprises proactively eliminate high-carbon-locked assets; with respect to incremental investment, enterprises in heavy-asset industries actively deploy new energy businesses. The key to asset replacement lies in timing the technological generational change appropriately. Acting too early may expose enterprises to the risk of technological immaturity during the transition, while acting too late may result in the loss of market opportunities. By eliminating outdated production capacity and deploying new businesses, enterprises can accomplish the value chain leap. This path plays a decisive role in asset-heavy industries.

The aforementioned three paths are not mutually exclusive but exhibit significant synergies. Innovation compensation offers technical support for market premiums, asset replacement liberates resource space for innovation activities, and collectively, these three paths form a dynamic system of carbon risk-driven enterprise value creation. Enterprises at various stages of development may select different combinations of paths: technology-leading enterprises are inclined to favor the innovation compensation-led model, brand-advantaged enterprises concentrate on the market premium path, and traditional asset-heavy enterprises depend more on asset replacement to achieve transformation. This diversity of path choices precisely embodies the rich practical manifestations of Porter’s hypothesis within a carbon-constrained environment. Therefore, we propose hypothesis H1b:

H1b. Carbon risk exerts a significant positive impact on the value creation of high-carbon-emitting firms.

6. Conclusions, Policy Implications and Prospects

6.1. Research Findings and Theoretical Discussion

In recent years, with the growing severity of global climate change and the deepening implementation of the “Dual Carbon” goals, carbon risk has become a critical factor that cannot be ignored in the process of corporate value creation. Using a sample of listed companies in high-carbon industries on China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-shares from 2012 to 2022, this study empirically examines the impact mechanism of carbon risk on corporate value creation by constructing a comprehensive carbon risk evaluation indicator system and employing a two-way fixed effects model. The findings reveal several key insights:

First, carbon risk exerts a significant inhibitory effect on value creation in high-carbon-emitting enterprises. This conclusion remains robust after a series of robustness tests, indicating that under the current institutional environment and technological conditions, carbon risk manifests more as an operational burden than an innovation opportunity for firms.

Second, the inhibitory effect of carbon risk demonstrates notable heterogeneity. Specifically, non-state-owned enterprises (NSOEs) experience more pronounced negative impacts on value creation due to stronger financing constraints and limited policy support. Small-sized firms, constrained by limited resource reserves and weaker risk resilience, are at a relative disadvantage when coping with carbon risk. Meanwhile, younger enterprises, lacking experience and transformation capabilities, are more vulnerable to the shocks induced by carbon risk.

Notably, the competitive hypothesis H1b derived from the Porter Hypothesis—that carbon risk promotes value creation—lacks empirical support in this study. This finding diverges from classical theoretical expectations and particularly reveals the boundaries of the Porter Hypothesis’s applicability within China’s institutional context, carrying profound theoretical and practical implications:

1. Institutional Environment and Market Mechanism Constraints: The effectiveness of the Porter Hypothesis relies on a well-developed institutional environment. In the early stages of China’s carbon market development, the price discovery function of carbon emission rights remains underdeveloped, with persistently low carbon prices failing to provide effective innovation incentives for firms. Concurrently, supporting mechanisms such as green technology trading markets and green financial systems are still under construction. Consequently, even if firms engage in low-carbon innovation, they struggle to attain adequate economic returns through market channels. Particularly for state-owned enterprises (SOEs), soft budget constraints and policy-imposed burdens further dilute the incentivizing effect of carbon price signals, hindering the manifestation of the “innovation compensation effect.”

2. Structural Differences in Firm Capabilities and Transformation Motivation: This study finds that while the inhibitory effect of carbon risk is relatively weaker in SOEs and large firms, the promoting effect remains insignificant. This insight is highly revealing: although SOEs possess stronger risk resilience due to resource advantages and policy access, their unique governance structures and evaluation systems often lead them to adopt “compliance-oriented” rather than “innovation-oriented” strategies. Relatively conservative innovation cultures and lengthy decision-making chains constrain their ability to transform environmental pressures into innovation opportunities.

3. Timing Mismatch Between Costs and Benefits: Compliance costs and equipment upgrade expenses triggered by carbon risk are immediate, whereas returns on innovation investments are characterized by significant time lags and uncertainty. Faced with short-term performance assessments and financing constraints, firms tend to perceive carbon risk as a cost item rather than an investment opportunity. This decision-making preference further weakens the manifestation of the Porter Hypothesis effect.

4. Regional Disparities in Policy Enforcement: Significant regional variations exist in the enforcement of environmental regulations in China, which influences the emergence of the Porter Hypothesis effect. In regions with weaker environmental enforcement, firms tend to adopt end-of-pipe treatments rather than fundamental innovation. Conversely, in regions with stricter enforcement, firms often face urgent compliance pressures, leaving limited time windows for strategic innovation.

These findings not only explain why the Porter Hypothesis fails to fully materialize in the Chinese context but, more importantly, deepen our understanding of the synergistic effects among institutional environments, firm characteristics, and innovation policies. Particularly in transitional economies, the innovation-promoting effect of environmental regulations needs to be coupled with deeper institutional reforms and corporate governance improvements.

6.2. Policy Implications

Based on in-depth analysis of the research findings—particularly the inhibitory effect of carbon risk on corporate value creation and the limited applicability of the Porter Hypothesis in the Chinese context—this study proposes the following targeted policy recommendations.

First, it is essential to improve carbon pricing mechanisms and establish a multi-layered incentive system. This can be achieved by expanding the coverage of the existing carbon market to include high-emitting sectors such as steel and cement, while gradually reducing the proportion of free allowances to enhance the effectiveness of carbon price signals. For non-state-owned and small-scale enterprises that are more significantly affected by carbon risk, a dedicated green transition fund should be established to provide low-interest loans and technical subsidies, alleviating their financing constraints and transition pressures. Such differentiated policy design ensures balanced transmission of emission reduction pressures while providing appropriate buffering space for different types of enterprises.

Second, institutional environment building should be strengthened to transform compliance costs into innovation drivers. Given that carbon risk currently manifests more as a “cost effect” rather than an “innovation compensation effect,” supporting institutional development is crucial. It is recommended to establish a corporate carbon risk rating system linked to financing costs and market access, creating competitive advantages for firms that proactively engage in low-carbon innovation. Simultaneously, improvements in the green technology trading market and intellectual property protection will help ensure that enterprises obtain due economic returns from their low-carbon innovations, thus shifting corporate strategies from passive compliance to active innovation.

Third, differentiated guidance policies should be implemented to precisely support corporate green transition. Considering the heterogeneous impact of carbon risk, policy formulation must fully account for variations among enterprise types. For state-owned enterprises, their demonstrative role in green transition should be strengthened by incorporating carbon performance into executive evaluation systems. For non-state-owned and small-scale enterprises, targeted technical assistance and fiscal incentives should be provided to enhance their carbon risk management capabilities. For younger firms, green entrepreneurship support programs could be established to encourage low-carbon development from their early stages.

Fourth, green market demand should be cultivated to create value realization channels for low-carbon products. Measures such as low-carbon product certification and green consumption subsidies are recommended to stimulate market demand. Meanwhile, governments should prioritize low-carbon products in public procurement, creating institutional conditions for firms to gain market premiums through green innovation. This combination of demand-side pull and supply-side push will help form a virtuous cycle of “innovation–profit–re-innovation,” establishing the market foundation for the Porter Hypothesis to take effect.

6.3. Research Deficiencies and Prospects

This study has several limitations that warrant further exploration.

First, in terms of variable measurement, it should be noted that estimating firm-specific carbon risk using industry-level data entails certain measurement inaccuracies. Due to variations across firms in the same industry—such as differences in energy efficiency, adoption of clean technologies, and progress in low-carbon transition—an industry-average-based approach may not fully capture firm-level heterogeneity in carbon risk exposure. This limitation primarily stems from the lack of detailed, firm-level carbon emission disclosure in China. Future studies could develop more accurate measures if finer-grained, firm-specific emissions or energy use data become available.

Second, regarding research design, although a two-way fixed effects model was employed to control for endogeneity, the potential bidirectional causality between carbon risk and firm value cannot be completely ruled out. For example, firms with higher value may be better able to invest in low-carbon technologies, thereby lowering carbon risk. Future studies could address this issue by exploiting exogenous policy shocks as instrumental variables or applying causal identification strategies such as regression discontinuity design to provide more robust evidence.

Third, in terms of mechanism testing, this study focused on financial (debt financing costs) and innovation (R&D investment) channels. However, carbon risk may also affect firm value through broader mechanisms such as corporate governance, supply chain dynamics, or consumer behavior. Future research could apply moderating effect models or multidimensional panel data methods to examine these channels in greater depth.

Looking ahead, future work could advance in several directions. First, strengthen causal identification by leveraging natural experiments, such as carbon market expansion policies. Second, explore the role of digital technologies in monitoring and managing carbon risk. Third, conduct cross-country comparative studies to investigate how institutional contexts shape the value relevance of carbon risk, thereby informing the development of a global sustainable financial system. Moreover, as China advances its national carbon market and international policies such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism take effect, issues such as cross-border carbon risk transmission and innovation in carbon financial products also merit continued scholarly attention.