1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial activities are pivotal in driving economic growth and innovation, contributing significantly to the development of dynamic economies worldwide [

1]. For this reason, numerous studies have been conducted to identify the factors that promote early-stage entrepreneurial activities, recognizing their complexity and multifaceted nature [

2,

3]. Institutional theory provides a robust framework for understanding how formal and informal institutions affect entrepreneurial behavior [

4]. Within the realm of institutional theory, cognitive and normative institutions are recognized as foundational elements that affect societal behaviors and perceptions, significantly impacting entrepreneurial activities [

4,

5]. Cognitive institutions, encompassing shared knowledge and mental schemas, provide the frameworks that guide individuals in recognizing and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities. Normative institutions, on the other hand, embed values and norms that determine the social acceptability and support for entrepreneurial activities [

6].

In addition to institutional dimensions, the propensity for innovation—defined as the ability to generate and implement new ideas, products, or processes—has been widely acknowledged as a crucial driver of entrepreneurship [

7]. Innovativeness not only fosters economic growth but also enhances competitive advantage by enabling entrepreneurs to introduce novel solutions to the market. However, studies have also shown that innovativeness may not always lead to greater entrepreneurial success due to associated risks, uncertainty, and market entry barriers [

8,

9]. While various studies have applied institutional theory and innovativeness to entrepreneurship research, defining the drivers of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems remains challenging. Regulatory frameworks and economic incentives often fail to explain how entrepreneurship can fully achieve long-term sustainability [

3,

4]. Recent research highlights that social dynamics, particularly reciprocity, play an essential role in entrepreneurial ecosystems [

8,

9]. Reciprocity, broadly defined as a mutual exchange in social interactions, includes positive reciprocity, which fosters cooperation, and negative reciprocity, which can create adversarial dynamics.

Reciprocity fosters trust, collaboration, and resource sharing, all of which are critical for sustainability [

10]. Conversely, negative reciprocity may hinder entrepreneurial efforts by creating mistrust and adversarial relationships [

11]. The traditional factors alone do not account for how entrepreneurship can be directed toward long-term, sustainable growth. This study aims to fill this gap by introducing reciprocity, a fundamental aspect of social interactions, as a moderating factor in sustainable entrepreneurship environments. Positive reciprocity, characterized by cooperative and supportive behaviors, and negative reciprocity, marked by retaliatory actions, both play significant roles in affecting entrepreneurial activities [

12]. While positive reciprocity can enhance collaboration and trust, facilitating resource exchange and network building, negative reciprocity can foster distrust and adversarial interactions, hindering entrepreneurial success.

This study aims to address the limitations of prior research, which often emphasizes institutional and economic factors while neglecting the relational dynamics that are critical for sustainability. It explores the role of reciprocity as a moderating factor in sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. This research addresses the following key questions: (1) How do cognitive and normative institutions influence early-stage entrepreneurial activities? (2) What role does innovativeness play in shaping entrepreneurial ecosystems, and are its effects always positive? (3) How does reciprocity moderate the relationships between institutional environments, innovativeness, and entrepreneurial activities? By addressing these questions, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. Specifically, the primary objective of this study is to investigate these dynamics and provide insights into fostering sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. Positive reciprocity, characterized by cooperative and supportive behaviors, and negative reciprocity, marked by retaliatory actions, both play significant roles in affecting entrepreneurial activities [

13]. Positive reciprocity enhances collaboration and trust by facilitating resource exchange and network building, whereas negative reciprocity fosters distrust and adversarial interactions, which can hinder entrepreneurial success.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a literature review and hypotheses’ development based on institutional theory, innovativeness, and reciprocity.

Section 3 outlines the research model, data, and methodology used for the analysis.

Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis, followed by a discussion of the findings in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 concludes with theoretical and practical implications, along with limitations and suggestions for future research.

Therefore, this study uniquely explores the intricate dynamics between institutional environment dimensions, innovativeness, and reciprocity in the context of fostering sustainable early-stage entrepreneurial activities. By examining how positive and negative reciprocity moderate the relationships between cognitive and normative institutions, innovativeness, and entrepreneurial activities, this research not only expands the scope of the existing literature but also contributes valuable insights for sustainable policymaking. Academically, it will enhance our understanding of how institutional dimensions, innovativeness and reciprocity behaviors affect entrepreneurial activities. Practically, the findings can guide policymakers and educators in creating environments that not only encourage entrepreneurship but also ensure its sustainability, ultimately driving long-term economic development and innovation. For instance, insights into the role of positive reciprocity in enhancing sustainable institutional support can help design policies that foster cooperative behaviors among entrepreneurs [

14,

15]. Similarly, understanding the adverse effects of negative reciprocity can inform interventions aimed at mitigating its impact on the sustainability of entrepreneurial activities [

13].

Thus, this research seeks to make significant contributions to the fields of entrepreneurship theory by analyzing the complex interplay between institutional dimensions, innovativeness, and reciprocity. The insights derived from this study will not only advance academic discourse but also provide practical strategies for cultivating sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems globally that support long-term economic growth and innovation.

2. Theoretical Background

This study builds on institutional theory, innovativeness, and reciprocity to examine their impact on early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Institutional theory explains how societal norms, cognitive frameworks, and shared values shape individual and organizational behaviors [

4]. This study specifically focuses on the cognitive and normative dimensions of institutions, which influence entrepreneurial perceptions and behaviors [

5,

6].

Innovativeness is introduced as a critical enabler of entrepreneurship, allowing individuals and organizations to create and commercialize new ideas, products, or processes [

16]. Innovativeness enhances the ability to recognize and exploit opportunities, particularly in dynamic and uncertain environments [

17].

Finally, reciprocity, grounded in social exchange theory [

13], is incorporated as a moderating factor. Positive reciprocity (rewarding kind actions) and negative reciprocity (retaliating against unkind actions) are examined in terms of their ability to shape trust, collaboration, and resource exchange within entrepreneurial ecosystems. Together, these theoretical constructs form the foundation of this study and guide the development of the hypotheses.

2.1. Institutional Environment

2.1.1. Cognitive Institutions

The cognitive institutional dimension plays a pivotal role in institutional theory, particularly within entrepreneurship. Ref. [

4] defines cognitive institutions as “shared conceptions that constitute social reality and interpretative frames,” which consist of widely accepted knowledge and beliefs that shape societal perceptions and actions. The authors of [

5] expand on this view, suggesting that cognitive institutions comprise mental templates or schemas that are culturally endorsed and socially reinforced. These schemas guide individuals in understanding their roles and the behaviors expected in various social contexts, including entrepreneurial endeavors.

In entrepreneurship, the cognitive institutional dimension encompasses prevailing ideologies and cognitive frameworks that influence the identification, evaluation, and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities [

18]. These frameworks dictate the range of acceptable entrepreneurial behaviors and help establish the social legitimacy of entrepreneurial ventures. For instance, ref. [

1] highlights that cognitive institutions impact entrepreneurial outcomes by affecting how potential entrepreneurs assess risks and recognize opportunities. Ref. [

13] underscores the importance of cognitive institutions in reducing uncertainty in economic activities, including entrepreneurship. Cognitive institutions provide a “rule set” that aids individuals in navigating complex environments, which is crucial in the uncertain and dynamic realm of entrepreneurship. Additionally, ref. [

19] suggests that cognitive institutions not only frame the environment in which entrepreneurs operate but also influence their ability to recognize and act on new opportunities.

The dynamic relationship between cognitive institutions and entrepreneurial behavior remains a crucial area of research in understanding how entrepreneurs thrive in various institutional contexts. Empirical studies have demonstrated a strong link between cognitive institutions and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Specifically, enhanced access to knowledge and well-developed cognitive frameworks promote entrepreneurial success, particularly during the initial stages of business development [

20,

21,

22]. Cognitive frameworks shared among firms and the workforce play a significant role in enhancing the sustainability of entrepreneurial ecosystems, as highlighted by [

23]. In summary, empirical evidence robustly supports the idea that the cognitive aspects of the institutional environment are positively associated with early-stage entrepreneurial activities, highlighting the critical role of cognitive institutions in fostering dynamic and vibrant entrepreneurial environments that are also sustainable.

H1-1: Cognitive institutions are positively associated with early-stage entrepreneurial activities.

2.1.2. Normative Institutions

Normative institutions are fundamental components of the institutional framework that shape societal behaviors by establishing and enforcing norms and values. According to [

6], normative systems consist of values, which represent conceptions of what is desirable, and norms, which prescribe specific behavioral expectations within a society. These institutions embed ethical and moral standards that directly impact both individual and collective actions, thereby determining the social acceptability and support mechanisms for various activities, including entrepreneurship [

6,

24].

Normative institutions play a critical role in shaping early-stage entrepreneurial activities by defining the sociocultural environment that either supports or inhibits the initiation of new ventures. In contexts where entrepreneurship is highly valued and supported by normative beliefs, there is generally a higher rate of startup activities. Cultures that advocate for risk-taking and value innovation are particularly conducive to fostering entrepreneurial success [

25]. This perspective is corroborated by the authors of [

26,

27], who find that various institutional factors, including normative beliefs, significantly impact entrepreneurial activities across different countries.

Empirical evidence highlights the positive influence of normative institutions on early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Ref. [

28] argues that cultural and social environments that promote entrepreneurial intentions, including positive societal attitudes and reduced fear of failure, significantly influence individuals’ decisions to pursue entrepreneurship. Similarly, ref. [

29] demonstrates that environments characterized by lower levels of fear of failure and positive entrepreneurial examples are associated with higher levels of entrepreneurial activity. Conversely, environments characterized by normative constraints that discourage entrepreneurial risks can suppress the entrepreneurial spirit, as individuals may be reluctant to engage in new ventures due to the fear of social stigma associated with failure [

30]. These studies illustrate the importance of supportive normative environments in fostering dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystems by providing cultural endorsement and institutional backing for entrepreneurial endeavors that promote long-term sustainability and ethical business practice.

In summary, normative institutions provide societal support, cultural endorsement, and reduced barriers to entrepreneurial activities, ultimately fostering dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystems.

H1-2: Normative institutions are positively associated with early-stage entrepreneurial activities.

2.2. Innovativeness

Innovativeness, defined as the propensity to generate and implement new ideas, products, or processes, has been recognized as a critical driver of entrepreneurship [

16]. The concept includes the ability to transform creative ideas into viable business ventures, thereby stimulating economic growth and competitive advantage [

7]. Innovativeness involves both the creation of novel solutions and the successful exploitation of these innovations in the market [

17]. This dual capacity for creation and commercialization is essential for entrepreneurs seeking to differentiate themselves in a competitive landscape [

31].

While innovativeness is often treated as a distinct construct, it can also be viewed as deeply embedded within the institutional perspective. Institutions, particularly cognitive and normative dimensions, play a critical role in shaping the environment in which innovativeness emerges and thrives. Cognitive institutions provide mental frameworks and shared knowledge that facilitate the identification of innovative opportunities, while normative institutions embed cultural norms and values that reward creativity and entrepreneurial risk-taking. In this sense, innovativeness can be considered both an outcome and an integral component of well-developed institutional systems.

The capacity for innovation is critical for the successful initiation of new businesses. It enables individuals and organizations to identify and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities, which are fundamental to venture creation. As the authors of [

32] argue, entrepreneurial orientation—including innovativeness—plays a pivotal role in recognizing and capitalizing on opportunities across both hostile and benign environments. Ref. [

33] describes innovativeness as a behavior-based construct that mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance. This highlights how innovative behavior transforms entrepreneurial potential into measurable success. Entrepreneurs with high levels of innovativeness exhibit resilience, adapt to market changes, overcome resource constraints, and develop unique value propositions.

Cultural factors significantly shape the environment in which innovativeness thrives. As the authors of [

34,

35] point out, cultural norms and values promoting creativity, openness, and entrepreneurial attitudes enhance innovative potential. Societies prioritizing experimentation and celebrating entrepreneurial achievements create fertile ground for innovation-driven ventures. Ref. [

36] further discusses how national culture and societal values can establish a supportive environment for innovation, facilitating entrepreneurial activity. For instance, countries with educational systems and institutional frameworks emphasizing creative problem-solving and technical skill development foster innovation ecosystems that benefit early-stage entrepreneurs. These systems not only encourage creativity but also provide the technical resources necessary for translating ideas into successful ventures.

Recent empirical studies further highlight the importance of innovativeness in driving early-stage entrepreneurial success. Ref. [

9] demonstrates that regions with a strong history of innovation consistently exhibit higher entrepreneurial activity, supported by robust ecosystems including research institutions, supportive government policies, and private sector collaborations. These findings align with the view that innovativeness is nurtured by institutions, particularly those fostering research, development, and collaboration across sectors. Ref. [

37] confirms that innovation-focused environments result in higher rates of business formation and sustainable growth. Similarly, ref. [

38] argues that innovative startups secure funding more effectively and achieve market traction by leveraging novel technologies and fostering investor relationships. By building long-term partnerships with stakeholders and embracing cutting-edge solutions, these startups not only achieve market success but also contribute to broader economic growth.

From a policy perspective, fostering innovativeness requires addressing regional and sector-specific dynamics. Ref. [

19] emphasizes the need for tailored entrepreneurship policies that align with the unique characteristics of local industries and innovation ecosystems. For example, technology-driven industries often require different support mechanisms compared to traditional sectors like agriculture or manufacturing. Regional factors such as access to research funding, skilled labor, and infrastructure also play a crucial role in shaping effective innovation policies. Institutions that emphasize innovation as a core value, such as those promoting education, R&D investment, and entrepreneurial networks, are critical in fostering sustained innovative capacity. Tailored approaches maximize innovation drivers, contributing to sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems and economic development.

Institutions are equally vital in promoting innovativeness. Normative institutions that reward creativity and entrepreneurial risk-taking create an enabling environment for innovation. At the same time, cognitive institutions provide the mental frameworks and knowledge resources necessary to exploit new opportunities [

13,

23]. This interaction between institutions and innovativeness highlights that the latter can be seen as an embedded characteristic of institutional systems, where cognitive frameworks enable ideation and normative values drive its commercialization. Conversely, environments lacking institutional support discourage risk-taking and limit entrepreneurial initiatives. For example, societies that stigmatize failure may suppress entrepreneurial ambitions, reducing overall innovation. Aligning policy efforts with cultural and cognitive factors is therefore essential for fostering innovation-driven entrepreneurship.

In conclusion, the literature strongly supports the hypothesis that innovativeness positively impacts early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Regions promoting innovation experience higher rates of new business formation, stronger market penetration, and better funding access. Innovativeness also serves as a critical enabler for long-term entrepreneurial success, sustaining competitive advantages in a rapidly evolving global economy. By conceptualizing innovativeness as both a standalone driver and an embedded aspect of institutions, this study emphasizes the critical interplay between institutional environments and innovative capacity. Leveraging cultural, institutional, and policy-based strategies to enhance innovation enables societies to foster dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystems that drive economic growth and innovation.

H2: Innovativeness has a positive effect on early-stage entrepreneurial activities.

2.3. Reciprocity

2.3.1. Reciprocity and Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activities

Reciprocity, a foundational element of social interactions, embodies the innate drive to respond to another person’s actions [

12]. This concept is divided into two contrasting aspects: positive and negative reciprocity. Positive reciprocity is the inclination to reward those who have treated us kindly, while negative reciprocity is the urge to punish those who have been unkind. Both actions—rewarding and punishing—can alter the payoffs for both parties involved. When one chooses to reward, their own payoff might decrease while the other’s increases. Conversely, punishing can reduce the punisher’s payoff and further diminish the recipient’s payoff. Reciprocal decisions are deeply rooted in the history of interactions between the parties; they are not merely reactive but are also shaped by past exchanges and have significant implications for future outcomes. Thus, reciprocal behavior reflects a complex interplay of personal gains, social norms, and the desire to maintain balanced relationships. Through these reciprocal actions, social bonds are either strengthened or weakened, influencing the dynamics of ongoing and future interactions.

For entrepreneurs, cultivating networks and social interactions is critical to their success, as their activities often revolve around exchanging resources, knowledge, and products. A key element in this process is the willingness to engage in positive reciprocity, which involves rewarding kind actions from others. This inclination can significantly enhance entrepreneurial activities, as noted by [

39], because reciprocal actions are embedded in all exchange processes between entrepreneurs and their networks. Positive reciprocity fosters cooperation, which is crucial for maintaining and developing business relationships, particularly when formal contracts are weak or unenforceable. Moreover, ref. [

40] highlights that positive reciprocity can be a pivotal factor for entrepreneurs in securing venture capital or forming alliances with larger companies. This cooperative behavior not only supports short-term gains but also encourages trust, long-term partnerships, and sustainable entrepreneurial activities by building resilient networks.

Conversely, negative reciprocity, which entails retaliating against perceived offenses, can also play a role in entrepreneurial contexts, especially in bargaining situations. According to [

41], asserting one’s position by responding to offenses can be important for maintaining a strong bargaining stance, which is critical for achieving higher financial margins. However, when approached strategically, negative reciprocity can serve as a protective mechanism that safeguards sustainable entrepreneurial activities by ensuring fairness and discouraging exploitative behavior.

However, extremes of both positive and negative reciprocity can be detrimental to entrepreneurial success [

13]. Excessive positive reciprocity, where entrepreneurs incur high personal costs to help others, can significantly reduce their profits. Similarly, high levels of negative reciprocity, characterized by a readiness to seek revenge regardless of the cost, can not only diminish profits but also damage the entrepreneur’s reputation. Such behavior may be perceived as non-cooperative, leading others to avoid business dealings with the entrepreneur.

In conclusion, while both positive and negative reciprocity can contribute to sustaining and advancing entrepreneurial activities to some extent, they must be balanced. The integration of reciprocity into entrepreneurial behavior should align with sustainable entrepreneurial activities, ensuring that relationships are maintained, resources are utilized effectively, and long-term viability is prioritized. Excessive reciprocity, in either form, can hinder entrepreneurial success by reducing profitability and damaging relationships. Therefore, entrepreneurs should strive for a measured approach to reciprocity to optimize their business outcomes.

2.3.2. Moderating Effects of Reciprocity

The institutional environment, characterized by formal regulations and supportive norms, plays a pivotal role in fostering entrepreneurial activities [

15]. This foundational support is significantly enhanced by the presence of positive reciprocity within social interactions. Positive reciprocity fosters trust, reduces transaction costs, and promotes effective collaboration among stakeholders [

10,

14]. It is particularly advantageous in contexts where formal contracts are weak. As highlighted by [

19], entrepreneurs involved in resource exchanges—such as knowledge, services, and capital—benefit substantially from positive reciprocity, which amplifies the advantages provided by institutional support. This synergy between positive reciprocity and institutional environments supports sustainable entrepreneurial activities by reinforcing trust-based networks and reducing reliance on rigid formal mechanisms. Collectively, these studies confirm that positive reciprocity moderates the relationship between institutional environments and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. High levels of positive reciprocity enhance the effectiveness of institutional frameworks, ensuring long-term viability and sustainability in entrepreneurial endeavors [

42].

Conversely, negative reciprocity, which involves retaliatory actions in response to perceived wrongs, significantly moderates the relationship between institutional environments and early-stage entrepreneurial activities, often weakening this dynamic. Studies indicate that negative reciprocity can severely undermine the entrepreneurial climate by fostering distrust and obstructing cooperation. Ref. [

41] argues that negative reciprocity cultivates a contentious atmosphere that erodes trust and cooperation—elements crucial for the effectiveness of institutional support mechanisms intended to promote entrepreneurship. This erosion of trust not only disrupts immediate collaboration but also poses a significant barrier to the sustainable development of entrepreneurial ecosystems. This antagonistic environment can deter stakeholders from engaging openly and supportively, as proposed by [

13], thereby reducing the efficacy of institutional policies designed to aid entrepreneurs. The detrimental impact of negative reciprocity on social exchanges is further explored by [

14], who note that it disrupts the flow of essential information, resources, and support necessary for early-stage entrepreneurial success. Such disruptions hinder the innovation and adaptability required for sustainable entrepreneurial activities, creating challenges for long-term enterprise growth. Overall, the literature consistently demonstrates that negative reciprocity weakens the relationship between institutional environments and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. By fostering a hostile and uncooperative atmosphere, negative reciprocity undermines the sustainability and resilience of entrepreneurial ventures, counteracting the benefits of supportive institutional frameworks.

H3-1: Positive reciprocity moderates the relationship between the institutional environment and early-stage entrepreneurial activities, such that the relationship is stronger in the presence of high positive reciprocity.

H3-2: Negative reciprocity moderates the relationship between the institutional environment and early-stage entrepreneurial activities, such that the relationship is weaker in the presence of high negative reciprocity.

In the entrepreneurial landscape, positive reciprocity significantly moderates the relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Ref. [

14] highlights that high levels of positive reciprocity allow entrepreneurs to leverage institutional environments more effectively, resulting in robust entrepreneurial outcomes. This relationship underscores the importance of fostering sustainable entrepreneurial activities by leveraging cultural and social factors to create resilient and adaptable ecosystems [

11]. Additionally, fostering positive reciprocal behaviors within entrepreneurial ecosystems is essential. Understanding how institutional supports are utilized in various cultural contexts, particularly those emphasizing communal practices, can better support early-stage entrepreneurial activities [

43,

44]. Promoting positive reciprocity not only maximizes the benefits of institutional supports but also ensures that these supports contribute to the long-term sustainability and growth of entrepreneurial ventures, marking a critical area for future research and policy development [

13].

Conversely, in environments characterized by high levels of negative reciprocity, these benefits are often compromised. Negative reciprocity fosters mistrust and adversarial interactions, creating barriers to collaboration, knowledge sharing, and network building—components essential for the success of innovative activities [

41]. Empirical studies demonstrate that high levels of negative reciprocity reduce the cooperative behaviors necessary for iterative innovation processes and the development of new businesses [

13]. These dynamics discourage risk-taking and experimentation, critical elements for fostering sustainability and innovation, as entrepreneurs fear exploitation or retaliation [

34,

35].

H4-1: Positive reciprocity moderates the relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities, such that the relationship is stronger in the presence of high positive reciprocity.

H4-2: Negative reciprocity moderates the relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities, such that the relationship is weaker in the presence of high negative reciprocity.

3. Research Model, Data and Methodology

3.1. Research Model

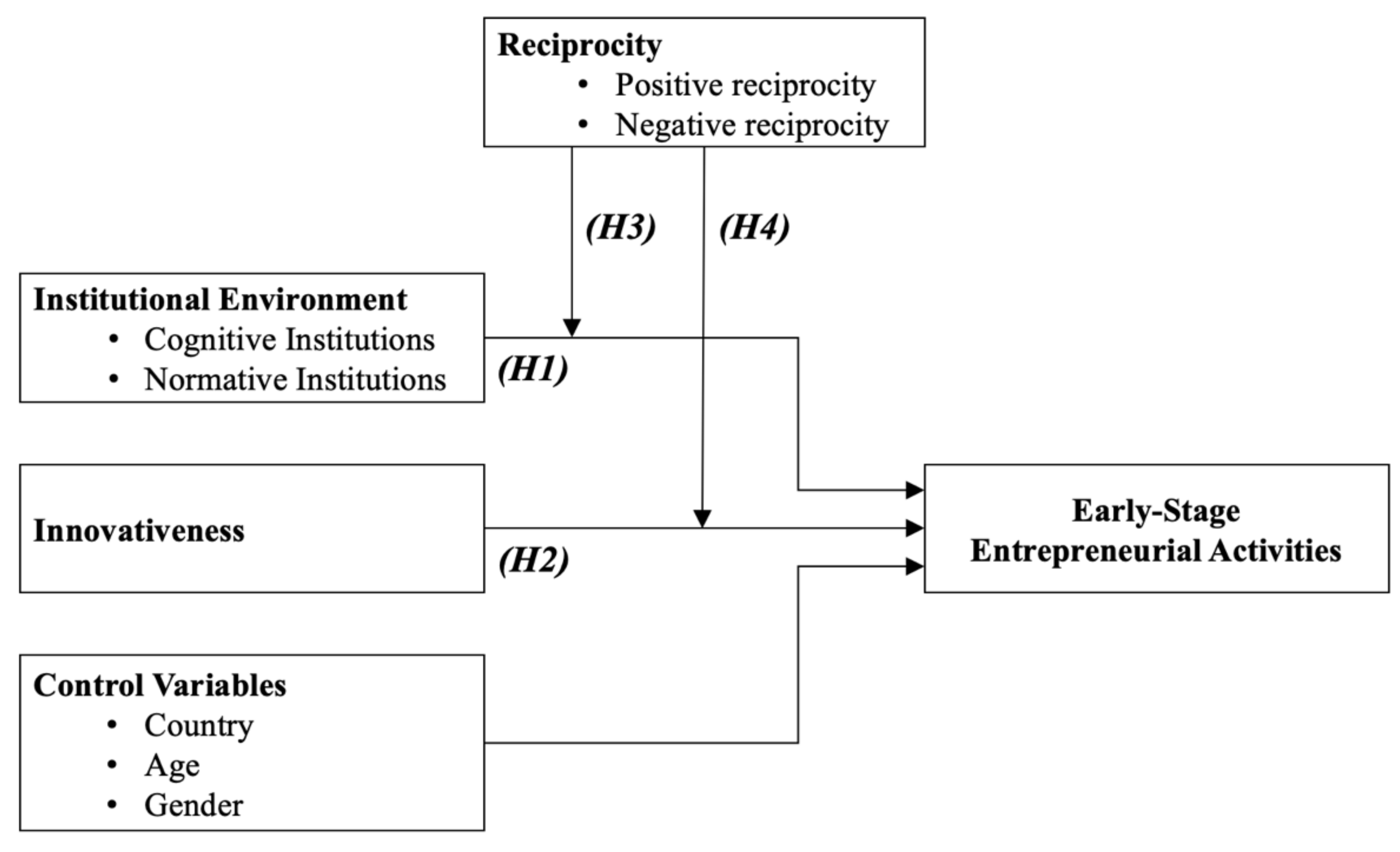

The research model is designed to understand how different forms of reciprocity—positive and negative—moderate the effects of institutional environments and innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities, as shown in

Figure 1. It posits that both the institutional environment and innovativeness play crucial roles in driving early-stage entrepreneurial activities. The moderating effects of reciprocity are critical in this model: positive reciprocity is expected to strengthen the relationship between these factors and entrepreneurial activities, while negative reciprocity is anticipated to weaken them. Control variables such as country, age, and gender are included to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing early-stage entrepreneurship.

3.2. Data and Operational Definition of Variables

This research utilizes data from two comprehensive sources: the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS) and the Global Preferences Survey (GPS). The GEM APS is an annual assessment at both the individual and national levels of entrepreneurial activity. It provides detailed data on the prevalence of entrepreneurship, the motivations of entrepreneurs, and the environment in which they operate. The 2019 GEM surveys include questions about entrepreneurial attitudes, activities, and aspirations across a broad cross-section of the population, offering a comprehensive view of entrepreneurial dynamics within each participating country. The GPS dataset captures individual preferences and social capital indicators, including reciprocity. Conducted in 2012, this global survey includes personal and social behaviors and preferences, providing critical insights into the cultural and social contexts that may influence economic and entrepreneurial activities.

This study utilizes both the GEM and GPS datasets, covering 21 countries: Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These countries were selected to provide a diverse and representative sample of different economic, cultural, and institutional environments.

Table 1 below defines each variable used in the analysis and summarizes the data indicators, scales, and sources utilized.

3.3. Methodology

This study employed logistic regression analysis to explore the relationships between the institutional environment, innovativeness, and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. This methodological approach allowed the researchers to assess the impact of the institutional environment and innovativeness on early-stage entrepreneurial activities while examining how positive and negative reciprocity modulate these effects. Equation (1) is extended to include interaction terms, reflecting the moderating effects of variables such as positive and negative reciprocity:

where

represents the log odds of the probability of the dependent variable Y being equal to 1, which is the occurrence of early-stage entrepreneurial activity.

denote independent variables and

are the coefficients for the main effects of the independent variables, including factors such as the institutional environment and innovativeness.

represents the interaction effects between reciprocity (either positive or negative) and other independent variables.

is the intercept term and

is the error term.

To address potential multicollinearity issues arising from the inclusion of interaction terms, this study employed mean centering for the independent and moderating variables. Mean centering is a preprocessing step that involves subtracting the mean of each variable from its individual values. This method ensures that the variables are rescaled to have a mean of zero while retaining their variance and overall distribution. The equations for calculating the mean of independent and moderating variables (2) and centering variables (3) are as follows:

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix for the variables used in this study, focusing on early-stage entrepreneurial activities and related factors. The cognitive institution (mean = 2.92, SD = 0.76) and normative institution (mean = 3.43, SD = 0.91) both show positive correlations with early-stage entrepreneurial activities, suggesting that stronger institutional frameworks may encourage entrepreneurship. However, innovativeness (mean = 1.52, SD = 0.77) exhibits a negative correlation with entrepreneurial activities, potentially indicating that highly innovative environments do not necessarily lead to higher entrepreneurial engagement, possibly due to higher risks or entry barriers. Positive reciprocity demonstrates negligible or slightly negative correlations with other variables, while negative reciprocity shows stronger negative correlations, particularly with entrepreneurial activities.

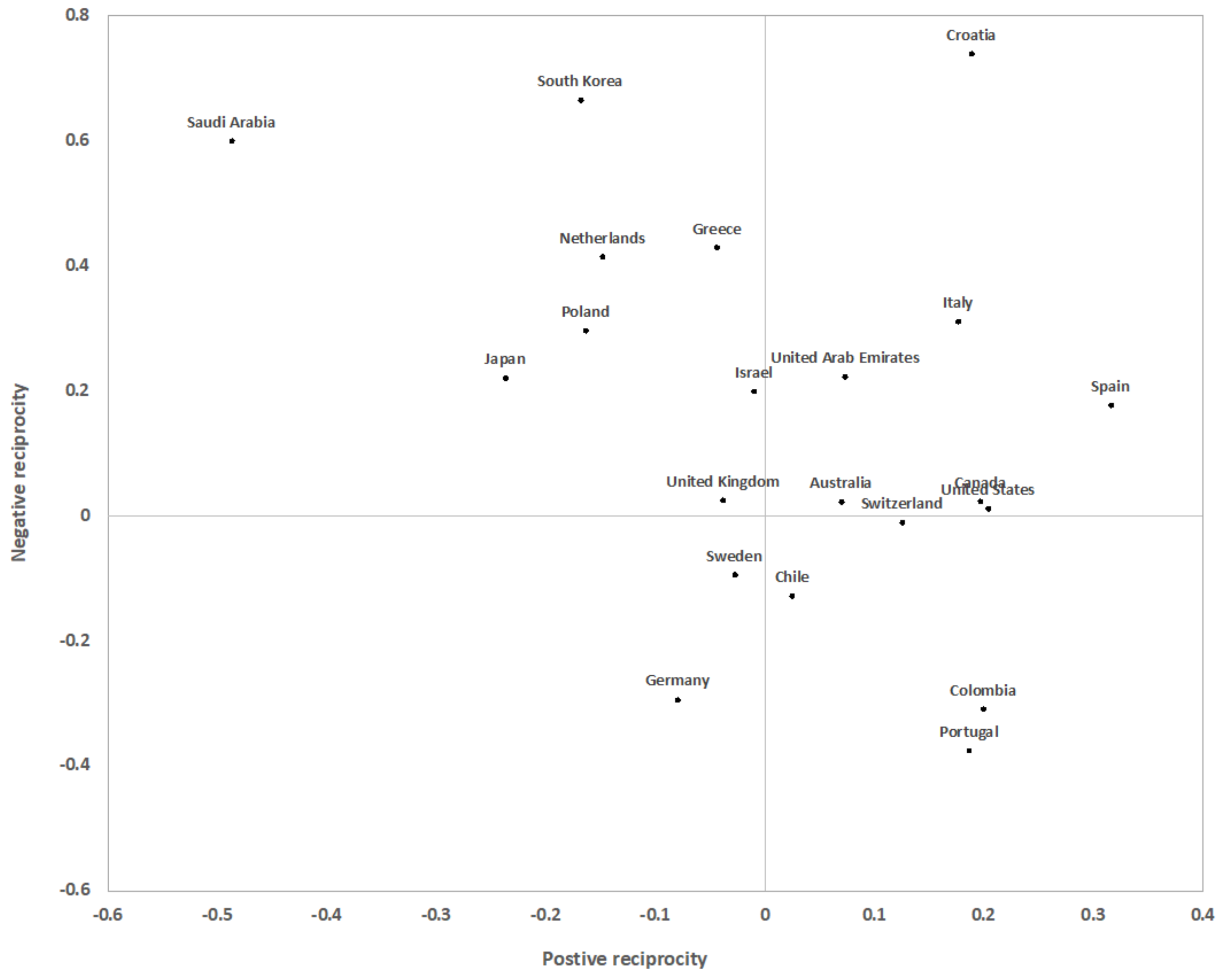

The scatter plot in

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of 21 countries based on their levels of positive and negative reciprocity. The x-axis represents positive reciprocity, while the y-axis represents negative reciprocity. Each point on the graph corresponds to a specific country, showing how they rank in terms of these two types of social interactions. Croatia stands out with high levels of both positive and negative reciprocity. The United Arab Emirates, Italy, and Spain also fall into this quadrant, indicating strong tendencies for both rewarding positive actions and retaliating against negative ones. The United States, Canada, Australia, and Switzerland show high positive reciprocity but low negative reciprocity, suggesting a cooperative culture with less inclination toward retaliatory actions. Saudi Arabia and South Korea exhibit high negative reciprocity and low positive reciprocity, indicating a higher propensity for retaliatory behavior and less frequent cooperation. Germany shows both low positive and negative reciprocity, indicating a relatively neutral stance in reciprocal interactions.

4.2. Impact of Factors on Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activities

In assessing the factors influencing early-stage entrepreneurial activities, two hierarchical models were estimated using logistic regression

Table 3. The results are reported in terms of coefficient estimates (β), odds ratios (OR), and marginal effects (ME). The OR represents the effect of a one-unit increase in an independent variable on the odds of the outcome occurring. The odds are the ratio of the probability of the event occurring to the probability of it not occurring. The ME measures the change in the probability of the outcome occurring due to a one-unit increase in the independent variable.

In Model 1, the cognitive institution was found to have a significant positive effect on the likelihood of engaging in early-stage entrepreneurial activities (OR = 1.57, ME = 0.09, p < 0.001). The normative institution also showed a positive, albeit smaller, relationship (OR = 1.05, ME = 0.01, p < 0.01). Innovativeness, however, had a significant negative impact on early-stage entrepreneurial activities (OR = 0.86, ME = −0.03, p < 0.001). In Model 2, positive reciprocity was found to have a negative impact on early-stage entrepreneurial activities (OR = 0.10, ME = −0.47, p < 0.1), suggesting a potential reduction in entrepreneurial activities. Similarly, negative reciprocity also had a negative impact (OR = 0.10, ME = −0.48, p < 0.05). Regarding control variables, age demonstrated a negative relationship with entrepreneurial activities in both models (OR = 0.96, ME = −0.01, p < 0.001). Gender (female) was positively related to entrepreneurial activities compared to males (OR = 1.11, ME = 0.02, p < 0.01).

4.3. Moderating Effects of Positive and Negative Reciprocity

Table 4 shows the moderating effects of positive and negative reciprocity on the relationship between institutional environment factors and innovativeness. To address potential multicollinearity issues arising from interaction terms, mean centering was applied to the independent and moderating variables before creating the interaction terms. Model 3 examines the moderating effects of positive reciprocity between institutional factors and innovativeness, while Model 4 focuses on negative reciprocity. In both models, the interaction between cognitive institution and reciprocity is not significant, indicating that neither positive nor negative reciprocity significantly modify the effect of cognitive institutions on entrepreneurial activities. In Model 3, the interaction between the normative institution and positive reciprocity is negative and significant (β = −0.22, OR = 0.81,

p < 0.05), suggesting that higher levels of positive reciprocity diminish the positive influence of normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities. Conversely, Model 4 reveals a significant positive interaction between normative institution and negative reciprocity (β = 0.13, OR = 1.14,

p < 0.1), indicating that higher levels of negative reciprocity may slightly enhance the positive effect of normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities. The interaction between innovativeness and positive reciprocity in Model 3 is positive and highly significant (β = 0.83, OR = 2.29,

p < 0.001), suggesting that positive reciprocity weakens the negative impact of innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities. In contrast, Model 4 shows that the interaction between innovativeness and negative reciprocity is negative and highly significant (β = −0.54, OR = 0.58,

p < 0.001), indicating that negative reciprocity exacerbates the negative impact of innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities.

To ensure the robustness of these findings, we conducted a robustness test using the bootstrapping method with 1000 resamples. Bootstrapping is an iterative resampling procedure that evaluates the stability and reliability of estimated coefficients by calculating their confidence intervals (CIs) across resamples. This method provides a non-parametric way to verify the consistency of the moderation effects and minimizes biases that could result from sampling variability. The results from the bootstrapped analyses confirmed the stability of the moderation effects observed in Models 3 and 4. Specifically, when the bootstrapped CIs do not include 0, the coefficients are considered statistically significant, indicating that the results are not highly sensitive to sampling variability. This confirms that the observed moderation effects are robust and reliable.

4.4. Simulation of Moderating Effects for Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activities

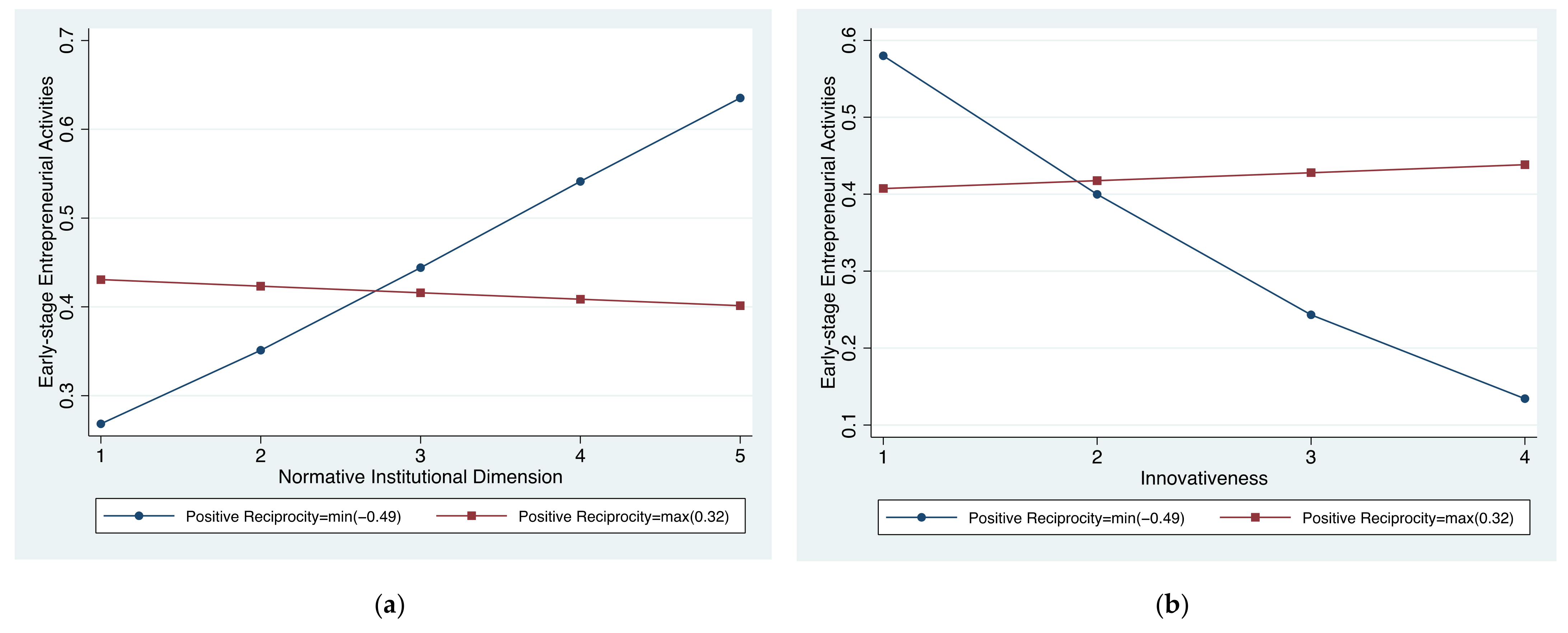

Figure 3 visually illustrates the moderating effect of positive reciprocity on the impact of two significant variables from the previous analysis—normative institutions and innovativeness—on early-stage entrepreneurial activities. As the normative institutional dimension increases, early-stage entrepreneurial activities also increase significantly when positive reciprocity is at its minimum. Conversely, when positive reciprocity is at its maximum, the increase in the normative institutional dimension has a negligible effect on early-stage entrepreneurial activities, showing a flat trend. As innovativeness increases, early-stage entrepreneurial activities significantly decrease when positive reciprocity is at its minimum. However, when positive reciprocity is at its maximum, the relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities shows a slight positive trend, indicating a buffering effect.

The graphs clearly demonstrate that positive reciprocity moderates the effects of both normative institutions and innovativeness on early-stage entrepreneurial activities. While positive reciprocity reduces the positive impact of normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities, it mitigates the negative impact of innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities. This visual representation highlights the critical role of positive reciprocity as a moderating factor, influencing the extent to which normative institutions and innovativeness affect early-stage entrepreneurial activities.

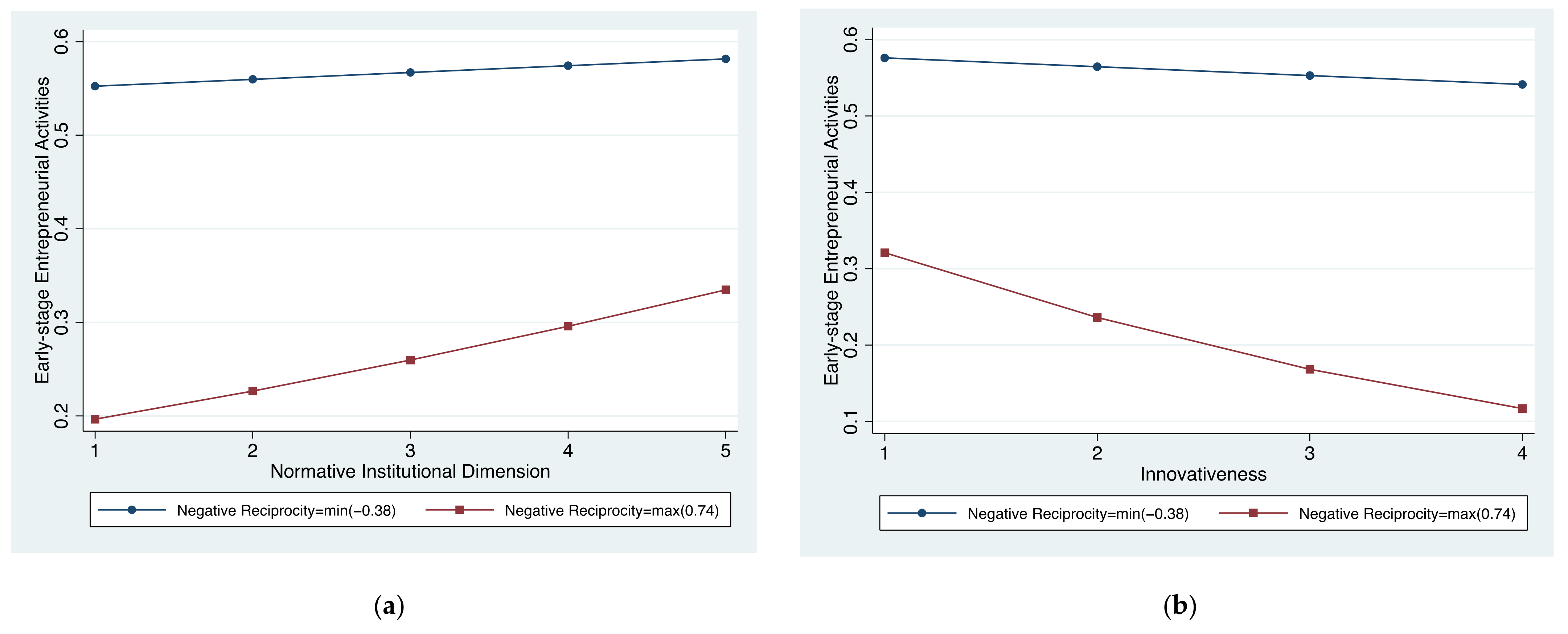

Figure 4 illustrates the moderating effect of negative reciprocity on the relationship between two significant variables from the previous analysis—normative institutions and innovativeness—and early-stage entrepreneurial activities. When negative reciprocity is at its minimum, the normative institutional dimension has a relatively stable effect on early-stage entrepreneurial activities, with a slight increase as the normative institutional dimension increases. In contrast, when negative reciprocity is at its maximum, an increase in the normative institutional dimension results in a noticeable increase in early-stage entrepreneurial activities. As innovativeness increases, early-stage entrepreneurial activities slightly decrease when negative reciprocity is at its minimum. However, when negative reciprocity is at its maximum, the relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities shows a strong negative trend.

The graphs clearly demonstrate that negative reciprocity significantly moderates the effects of both normative institutions and innovativeness on early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Negative reciprocity amplifies the positive impact of normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities, suggesting that in environments with high negative reciprocity, the positive influence of normative institutions becomes more pronounced. Conversely, negative reciprocity exacerbates the negative impact of innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities, indicating that in settings with high negative reciprocity, the adverse effects of innovativeness are intensified.

5. Discussion

This literature review highlighted the crucial role of cognitive institutions in shaping entrepreneurial behavior by providing mental templates and schemas that guide individuals in recognizing and exploiting opportunities [

1,

4]. Our empirical analysis corroborates this view, demonstrating a significant positive association between cognitive institutions and early-stage entrepreneurial activities (Model 1: OR = 1.57, ME = 0.09,

p < 0.001). This finding suggests that environments with well-developed cognitive frameworks facilitate entrepreneurial endeavors by reducing uncertainty and fostering a culture of innovation and risk-taking. However, our results further reveal that the effect of cognitive institutions is not significantly moderated by either positive or negative reciprocity (

Table 4, Models 3 and 4). This indicates that the influence of cognitive institutions on early-stage entrepreneurial activities is robust across different levels of reciprocity, implying that these foundational cognitive frameworks provide a stable base for entrepreneurship regardless of the social exchange context.

Normative institutions, which encompass societal norms and values, were also found to positively influence early-stage entrepreneurial activities, though to a lesser extent than cognitive institutions (Model 1: OR = 1.05, ME = 0.01,

p < 0.01). This supports previous findings that cultural endorsement and social support for entrepreneurship encourage new venture creation [

3]. Notably, the interaction between normative institutions and positive reciprocity was negative and significant (Model 3: β = −0.22, OR = 0.81,

p < 0.05), indicating that high levels of positive reciprocity may diminish the positive effect of normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities. This could be due to the possibility that excessive positive reciprocity leads to complacency or dependency, thereby reducing the entrepreneurial drive. Conversely, negative reciprocity slightly enhances the positive effect of normative institutions (Model 4: β = 0.13, OR = 1.14,

p < 0.1), suggesting that a certain level of competitive tension might stimulate entrepreneurial efforts by pushing individuals to assert themselves and their ventures more aggressively.

Contrary to the predominant view that innovativeness universally promotes entrepreneurial success, our findings indicate a significant negative relationship between innovativeness and early-stage entrepreneurial activities (OR = 0.86, ME = −0.03,

p < 0.001). This aligns with recent studies suggesting that the risks and uncertainties inherent in innovative ventures can deter entrepreneurial efforts. For example, innovation enhances firm performance and survival. However, it does not always translate into higher rates of new firm creation due to substantial risks and uncertainties [

45]. Similarly, ref. [

8] emphasizes that although innovation is often linked to growth, it can also pose significant barriers to entrepreneurial activity. The study shows that high failure rates and financial uncertainty associated with innovation may discourage potential entrepreneurs, counterbalancing the perceived benefits of innovativeness.

In a study on Brazilian startups, ref. [

46] also found that the high costs and uncertainties associated with innovative activities can hinder entrepreneurial success, particularly in dynamic environments. In contrast, in developed countries like Germany and the United States, while the positive impacts of innovativeness are more frequently reported, negative aspects such as high failure rates and financial risks have also been documented [

9,

47]. Previous research often highlights the positive aspects of innovativeness, such as the ability to introduce novel solutions and gain a competitive advantage [

7]. However, the potential downsides, including high failure rates and financial risks associated with innovation, have not been equally emphasized.

The moderating effects of reciprocity on the relationship between innovativeness and entrepreneurial activities are particularly noteworthy. Our findings suggest that positive reciprocity significantly mitigates the negative impact of innovativeness on entrepreneurial activities (Model 3: β = 0.83, OR = 2.29,

p < 0.001). This is consistent with the findings of [

12], who highlight that positive reciprocity fosters a collaborative environment conducive to resource sharing and trust-building, thereby reducing the risks associated with innovation. These supportive social interactions can enhance entrepreneurial outcomes by providing the necessary networks and resources to navigate the uncertainties of innovation.

Conversely, negative reciprocity exacerbates the negative impact of innovativeness (Model 4: β = −0.54, OR = 0.58,

p < 0.001). This finding supports the conclusions of [

13], who found that negative reciprocity creates a challenging environment, inhibiting entrepreneurial growth due to mistrust and adversarial behaviors. Ref. [

39] further emphasizes that social competence, including the ability to manage negative social exchanges effectively, is crucial for entrepreneurs to leverage opportunities and overcome obstacles. In environments characterized by mistrust and adversarial interactions, the potential benefits of innovativeness are less likely to be realized, as such conditions hinder the effective exploitation of innovative opportunities.

These findings underscore the complex role that social factors, particularly reciprocity, play in shaping the outcomes of entrepreneurial activities. While positive reciprocity can act as a buffer against the risks of innovation, negative reciprocity may intensify these challenges, ultimately affecting the overall success of entrepreneurial ventures.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the moderating effects of positive and negative reciprocity on the relationships between cognitive institutions, normative institutions, and innovativeness in early-stage entrepreneurial activities, emphasizing their role in fostering sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Our findings demonstrate that cognitive and normative institutions play significant roles in shaping entrepreneurial behavior, but their effects are not uniform. Positive reciprocity enhances trust, cooperation, and resource sharing, creating an environment where entrepreneurial activities can thrive. In contrast, negative reciprocity introduces conflict and distrust, potentially undermining entrepreneurial efforts.

Moreover, innovativeness, while often regarded as a critical driver of entrepreneurial success, does not always guarantee positive outcomes. The effectiveness of innovation depends on the surrounding institutional and social context, highlighting the importance of balanced reciprocity.

From a policy perspective, fostering cognitive skills through education, promoting collaborative networks, and implementing conflict resolution mechanisms are crucial for sustaining entrepreneurial ecosystems. Furthermore, recognizing regional and contextual differences is essential for tailoring policies that address specific institutional dynamics.

In conclusion, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how institutions, innovativeness, and reciprocity interact to influence entrepreneurial ecosystems. The results offer valuable insights for theoretical advancements, policy frameworks, and practical strategies aimed at enhancing sustainable entrepreneurial environments.

The following sections elaborate on the theoretical contributions, practical implications, and future research directions derived from this study.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by analyzing the moderating effects of positive and negative reciprocity on the relationships between cognitive institutions, normative institutions, and innovativeness in early-stage entrepreneurial activities, highlighting their role in fostering a sustainable entrepreneurial environment. While previous studies primarily focused on the direct impacts of cognitive and normative institutions on entrepreneurship [

1,

3,

4], this research expands the framework by examining how these relationships are influenced by social exchange mechanisms, specifically reciprocity.

First, this study advances institutional theory by demonstrating that the effects of cognitive and normative institutions on entrepreneurial activities are moderated by positive and negative reciprocity, offering a more dynamic understanding of institutional impacts [

13,

21].

Second, it contributes to innovation literature by showing that innovativeness can have both positive and negative effects on entrepreneurial outcomes, depending on the nature of reciprocity [

15,

19].

Finally, this study offers an integrated framework that connects institutions, innovativeness, and reciprocity, providing a holistic perspective on their interplay in entrepreneurial ecosystems.

These contributions deepen our understanding of how institutional environments, innovativeness, and social interactions collectively shape entrepreneurial activities, offering a robust foundation for future research.

6.2. Policy and Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide significant policy and practical implications for policymakers, educators, and entrepreneurs aiming to foster sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems and enhance entrepreneurial activity.

First, policymakers should prioritize the development of educational programs that enhance cognitive skills essential for entrepreneurship. This includes integrating entrepreneurial thinking into school curricula and offering specialized training programs focused on critical thinking, problem-solving, and opportunity recognition. Research indicates that cognitive institutions play a crucial role in shaping entrepreneurial activities by providing mental schemas that facilitate decision-making and risk-taking [

1,

4,

13].

Second, positive reciprocity can enhance collaboration and resource sharing, which are critical for entrepreneurial success. Policymakers should create platforms and networks that facilitate cooperation among entrepreneurs, investors, and stakeholders. Initiatives such as innovation hubs, incubators, and accelerators can provide environments that foster trust and collaboration [

13,

14]. At the same time, it is important to avoid creating dependencies that may lead to complacency. Programs such as innovation challenges and hackathons can promote a balance between cooperation and individual initiative [

18,

39].

Third, negative reciprocity, characterized by retaliatory actions, can significantly undermine trust and cooperation in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Policymakers should focus on conflict resolution mechanisms and foster a culture of constructive feedback. Training programs on negotiation and conflict management can equip entrepreneurs with the tools needed to navigate adversarial interactions effectively [

13,

41].

Fourth, recognizing that institutional contexts differ across regions, tailored policy interventions are essential. In environments with strong cognitive and normative institutional support, initiatives should focus on enhancing collaborative networks and advanced training in innovation management [

35,

36]. Moreover, policies that support sustainable business practices and innovation ecosystems are vital for long-term entrepreneurial success [

9,

48].

These practical recommendations provide a roadmap for building balanced and resilient entrepreneurial environments, where institutions, innovativeness, and social reciprocity interact effectively to drive sustainable economic growth and innovation.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions of Research

While this study provides valuable insights, it also has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data restricts the ability to establish causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to capture how relationships between institutional dimensions, reciprocity, and entrepreneurial activities change over time.

Additionally, this study focuses on cognitive and normative institutions and reciprocity, but other potential moderating variables, such as regulatory support, market dynamics, and economic conditions, could be explored to provide a more holistic view of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Future research could also investigate sector-specific differences, which may reveal unique dynamics in different industries or markets. Furthermore, expanding the geographical scope to include more diverse contexts could help generalize the findings and understand regional variations. Finally, qualitative approaches, such as interviews or case studies, could complement quantitative data, providing deeper insights into the mechanisms behind these relationships.

Moreover, while this study included country, age, and gender as control variables, it was unable to consider additional factors such as education level or household income due to limitations in the GEM dataset. We acknowledge this as a limitation and suggest that future research incorporates these and other relevant variables, as they may provide a deeper understanding of early-stage entrepreneurial activities. Addressing this limitation could offer a more comprehensive analysis and contribute to building a more nuanced model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.