Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: An Ablative Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Climate Crisis via Conservative or Radical Reform Paradigms

Abstract

1. Introduction

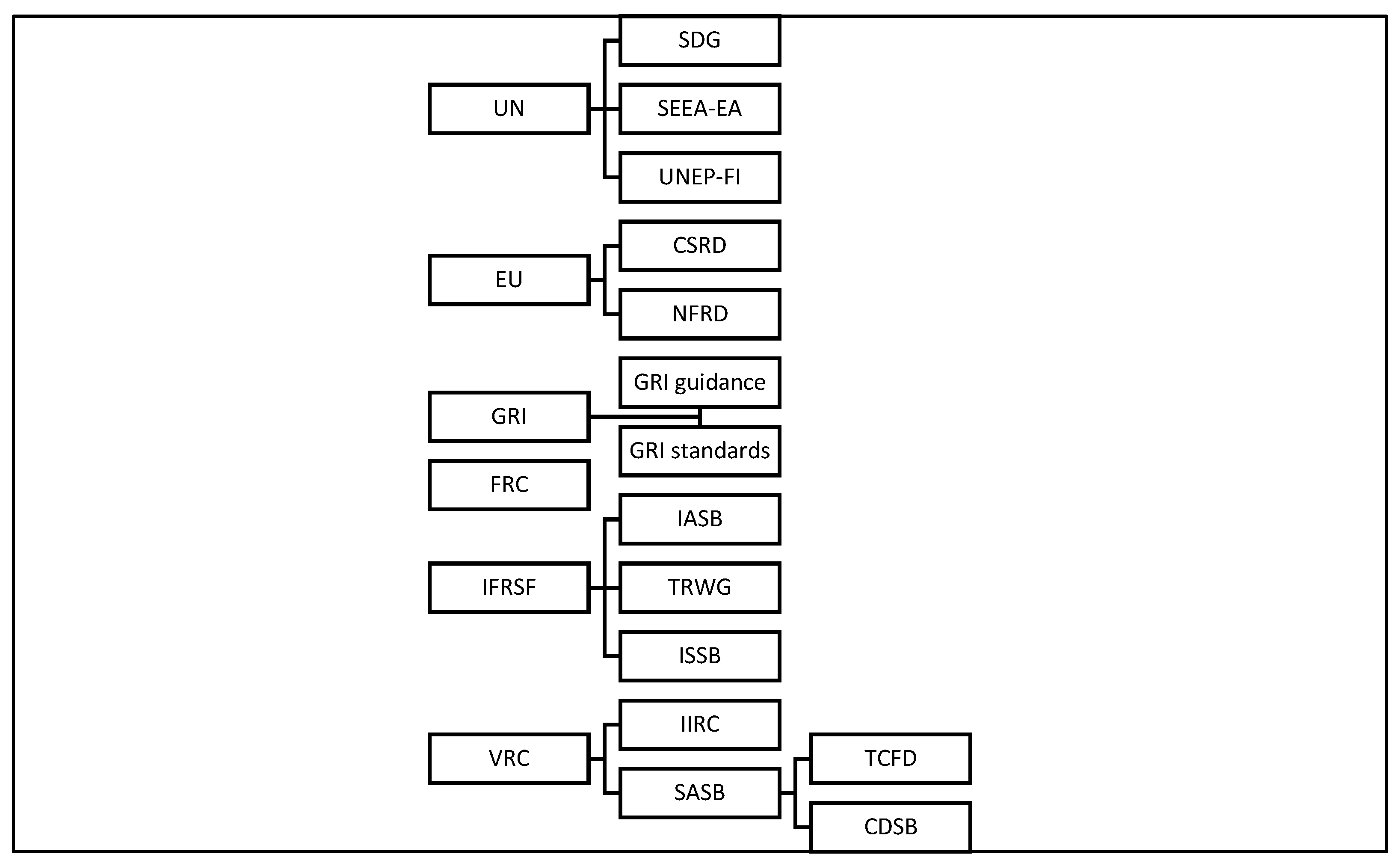

1.1. Problem, Institutions, and Themes

1.2. SAR Institutions and Issues

1.3. Reform Challenges

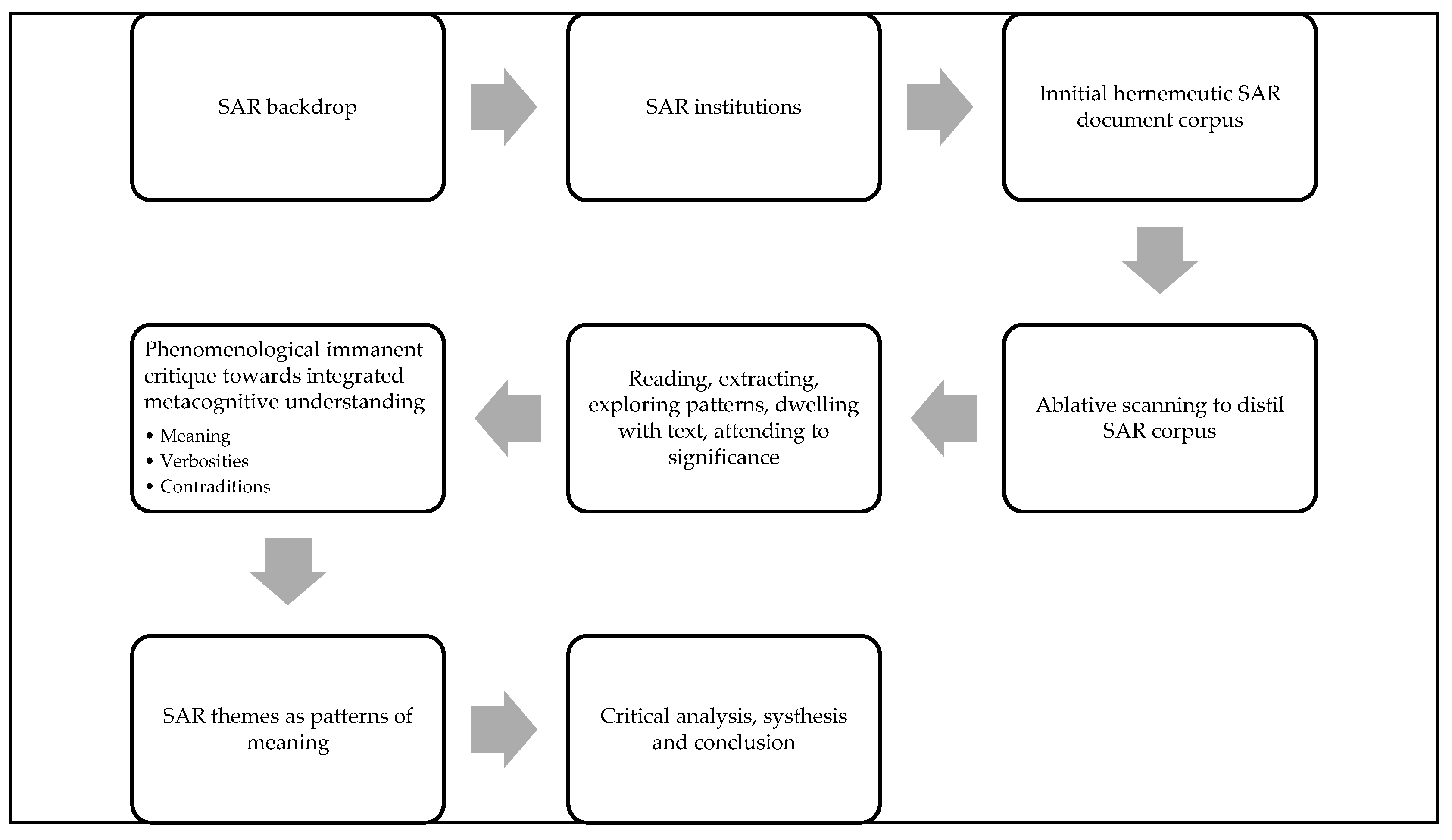

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Climate Crisis

3.2. Theme 2: Conservative Approach

3.2.1. Financial Reporting Council

3.2.2. IFRS Foundation (London)

3.2.3. International Sustainability Standards Board ISSB

3.2.4. Value Reporting Foundation (VRF)

3.2.5. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC)

3.2.6. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB)—San Francisco

3.2.7. Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFDs)

3.3. Theme 3: Radical Perspectives

3.3.1. United Nations

3.3.2. European Union Commission

3.3.3. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

3.3.4. B Corp or Better Corporations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARGA | Audit Reporting and Governance Authority, slated to replace FRC |

| ARTA | Ablative reflexive thematic analysis—technique to apply phenomenological hermeneutics by using personal experience to interpret texts |

| AUM | Assets under management |

| BIA | B Corp Integrated Assessment |

| CARE | Centre for Accounting Research Education |

| CCWG | Climate Change Working Group (UNEP FI) |

| CDP | Not-for-profit charity that runs the global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states, and regions to manage their environmental impacts. |

| CDSB | Climate Disclosure Standards Board is an international consortium of nine business linked to SASB that promulgates integration of natural with financial capital. |

| COP26 | UN Climate Change Conference (Glasgow, 2021) |

| CSR | Corporate Sustainable Reporting/Responsibility |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (EU-C) |

| EFRAG | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| EU-C | European Union Commission |

| FASB | Financial Accounting Standards Board. The US Securities and Exchange Commission recognizes it as the source of GAAP based FA and reporting standards. |

| FCA | Financial Conduct Authority’s (London) |

| FRC | Financial Reporting Council (London) ostensibly promotes transparency and integrity in business. It regulates auditors, accountants, and actuaries, and sets the UK’s Corporate Governance and Stewardship Codes. Slated replacement by ARGA. |

| FSB | Financial Stability Board a global organization that seeks to promote global financial stability (Basel) |

| GAAP | Generally Accepted Accounting Principles developed in the US. |

| GFANZ | Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases (mainly carbon dioxide C02 and methane CH4) |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative (Amsterdam) |

| Hermeneutic | Active, iterative textual interpretation where meaning emerges via metacognition within broader evolving context. Etymologically derived from Greek god, Hermes-messenger of the gods. |

| IASB | International Accounting Standards Board (London) |

| IFRS-F | International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (London) |

| IIRC | International Integrated Reporting Council-incorporated under IFRS-F with SASB |

| IOSCO | International Organisation of Securities Commissions (Madrid) is a worldwide association of national securities regulatory commissions, including the US Securities and Exchange Commission and the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA). |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board-offshoot of IFRS-F |

| ITF | Impact Task Force (G7) |

| Ithaca | Greek island in the Aegean Sea-the home of Ulysses. An aspirational destination |

| IVSC | International Valuation Standards Council |

| NFD | Non-Financial Disclosure |

| NFRD | Non-Financial Reporting Directive (EU-C, Brussels) |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (Paris) |

| Phenomenology | Research based on perceptions or subjective experiences |

| SAR | Sustainability accounting and reporting |

| SASB | Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (San Francisco) established in 2011. It sets standards independently to enhance capital markets efficiency by quality sustainability disclosure for investors. Now consolidated within the VRF |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals promulgated in the UN’s (2015) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 17 SDGs were identified to stimulate critical action (UNEP) |

| SDR | Sustainability Disclosure Requirements |

| SDS | Sustainability Disclosure Standards developed by the ISSB |

| SEEA-EA | UN System of Environmental-Economic Accounting-Ecosystem Accounting, developed and curated by the Statistics Division of the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs. SEEA EA is a statistical framework for organizing data about habitats and landscapes, measuring the ecosystem services, tracking changes in ecosystem assets, and linking this information to economic and other human activity. |

| SFDR | Sustainability Finance Disclosure Regulation (EU, Brussels) requires firms to report on their sustainability risks and impacts. In relation to traded products, UK firms engaged in EU business must comply with SFDR. |

| TCFD | Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures TCFD, instigated in 2015 by the Basel-based Financial Stability Board (FSB) |

| TFO | True and Fair Override when accounts depart from accounting standards to disclose material information that reflects a principal based true and fair view. |

| TFNFRS | Task Force on Non-Financial Reporting Standards (EFRAG) |

| TRWG | Technical Readiness Working Group (IFRS) |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| UNEP FI | United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (Geneva) is a global partnership between UNEP and the financial sector, involving 550 institutions that feed into its Climate Change Working Group (CCWG) |

| UNDESA | UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs that promulgates the SEEA-EA |

| VRF | Value Reporting Foundation, incorporates SASB and under auspices of IFRS-F |

References

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A global assessment: Can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Z. Today. BBC Radio 4. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0012svy (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Crawford, A.; Sculthorpe, T. The plastic Nile. Sky News, 21 March 2021. Available online: https://news.sky.com/video/the-plastic-nile-11999381 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Jill, A.; Warren, M. The naturalist’s journals of Gilbert White: Exploring the roots of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1835–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings, and Construction Sector; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Kubli, D.; Saner, P. The Economics of Climate Change: No Action Not an Option; Swiss Re Institute: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/climate-and-natural-catastrophe-risk/expertise-publication-economics-of-climate-change.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Church, J. Climate change scientific update. In Accounting for Sustainability and Responsible Investing, Centre for Accounting Research Education Conference; University of Notre Dame: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2021: The Heat Is on—A World of Climate: Promises Not Yet Delivered; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36991/EGR21_ESEN.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record—Temperatures Hit New Highs, Yet World Fails to Cut Emissions (Again); United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; Available online: https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43922 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- United Nations Environnent Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2024; United Nations Environnent Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D. Green Recovery Must End the Reign of GDP, Argue Cambridge and UN Economists; Bennett Institute for Public Policy: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/UNnaturalcapital (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- H. M. Government. Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing; HMG: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-government-green-financing (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Murphy, R. The UK Government-Approach to Sustainability Reporting Is Pure Greenwash; Tax Research Institute, Sheffield University Management School: Sheffield, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2021/10/19/the-uk-government-approach-to-sustainability-reporting-is-pure-greenwash/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Dasgupta, P. Nature: Our Most Precious Asset. Cambridge University 2021; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvPJALCZOeo (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Laine, M.; Tregidga, H.; Unerman, J. Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozick, R. Anarchy, State, and Utopia; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, L. On Anarchism. In Interview with Tom Lane. chomsky. info. 23 December 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Atmospheric CO2 Concentration; UNEP: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://wesr.unep.org/climate/essential-climate-variables-ecv/atmospheric-co2-concentration (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Liikanen, E. Global Sustainability Disclosure Standards for the Financial Markets; IFRS: Glasgow, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2021/11/global-sustainability-disclosure-standards-for-the-financial-markets/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Tiwari, K.; Khan, M.S. Sustainability accounting and reporting in the industry 4.0. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory, S.B.; Brooks, S.B. Managing corporate sustainability with a paradoxical lens: Lessons from strategic agility. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R. Impact: Reshaping Capitalism to Drive Real Change; Ebury Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/oxford-answers/reshaping-capitalism-drive-real-change (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Keynes, J.M. Treatise on Money; Macmillan: London, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Production Gap Report 2021. Available online: https://productiongap.org/2021report/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Kaplan, R.S. Accounting for climate change: The first rigorous approach to ESG reporting. In Proceedings of the Egyptian Online Seminars in Business, Accounting and Economics, Cairo, Egypt, 21 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feix, A.; Philippe, D. Unpacking the narrative de-contestation of CSR: Aspiration for change or defence of the status quo? Bus. Soc. 2018, 59, 129–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, D. ‘Blah, blah, blah’: Greta Thunberg lambasts leaders over climate crisis. The Guardian. 28 September 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/28/blah-greta-thunberg-leaders-climate-crisis-co2-emissions (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- France 24. Swiss to Hold High-Altitude Wake for Lost Glacier; AFP: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.france24.com/en/20190922-swiss-to-hold-high-altitude-wake-for-lost-glacier (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Veblen, T. Vested Interests, and the Common Man; B. W. Heubsch: New York, NY, USA, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Times. COP26: Carney’s $130tn Climate Pledge Is Too Big to Be Credible; Financial Times: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/87690ee9-c9b1-44b6-881b-368139560295 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. A critical review of the reporting of reflexive thematic analysis in Health Promotion International. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.A. Literature reviews of, and for, educational research: A commentary on Boote and Beile’s “Scholars before researchers”. Educ. Res. 2006, 35, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisigl, M.; Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Suddick, K.M.; Cross, V.; Vuoskoski, P.; Galvin, K.T.; Stew, G. The Work of Hermeneutic Phenomenology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. Thematic analysis: The ‘good’, the ‘bad’ and the ‘ugly’. Eur. Qual. Res. 2021, 11, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Sein und Zeit; Max Niemeyer Verlag: Halle (Saale), Germany, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Vorlesungen zur Phänomenologie des Inneren Zeitbewusstseins; Max Niemeyer Verlag: Halle (Saale), Germany, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 1993; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Narrative macro-structures. PTL J. Descr. Poet. Theory Lit. 1976, 1, 547–568. [Google Scholar]

- Saïd Business School. SBS Responsible Business Debate: Should Corporate Sustainability Reporting Be Mandated? University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IyzkKFgp6NU (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Pitt-Watson, J. Can ESG reporting be consistent with basic accounting principles? In Proceedings of the Accounting for Sustainability and Responsible Investing, Centre for Accounting Research Education Conference, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 21 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra, M.R. Forests and climate change mitigation. In Proceedings of the Global Business School Network: Race2Imagine Series, Online, 22 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N. The Scandal of Privatised Water Is Going to Blow. The Spectator. 16 September 2017. Available online: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-scandal-of-privatised-water-is-going-to-blow (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Financial Conduct Authority. Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and Investment Labels: Discussion Paper DP21/4; FCA: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/discussion/dp21-4.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Impact Taskforce. Time to Deliver: Mobilising Private Capital at Scale for People and Planet; Global Steering Group for Impact Investment (Trading as GSG): London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.impact-taskforce.com/media/gq5j445w/time-to-deliver-final.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Garvey, A.M.; Parte, L.; McNally, B.; Gonzalo-Angulo, J.A. True and fair override: Accounting expert opinions, explanations from behavioural theories, and discussions for sustainability accounting. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Reporting Council. Climate Thematic; FRC: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/ab63c220-6e2b-47e6-924e-8f369512e0a6/Summary-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Financial Reporting Council. FRC Climate Thematic. Reporting—How Are Companies Developing Their Reporting on Climate-Related Challenges? FRC: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/6d8c6574-e07f-41a9-b5bb-d3fea57a3ab9/Reporting-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Financial Reporting Council. Frequently Asked Questions: International Sustainability Standard Setting: Factsheet for Preparers; Financial Reporting Council: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-sustainability-standards-board/issb-frequently-asked-questions/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- SASB; CDSB. Converging on Climate Risk; Sustainability Accounting Standards Board: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SASB. SASB Standards Engagement Guide for Companies and Investors; SASB Standards: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/knowledge-hub/engagement-guide/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Bauer, R.; Orlitzky, M. Sustainable development and financial markets: Old paths and new avenues. Bus. Soc. 2015, 55, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C. Hijacking ‘Sustainability’ (Accounting): The Case of ‘ESG’ and the IFRS Egyptian Online Seminars in Business. Accounting and Economics. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBAE4jfkLr8 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- United Nations. System of Environmental Economic Accounting—Ecosystem Accounting; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://seea.un.org/ecosystem-accounting (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Commission. Corporate Sustainability Reporting; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en#standards (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- KPMG. CSRD & Sustainability Reporting Growing Pains: Balancing Regulatory Burden with Sustainable Business Transformation; KPMG Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2025; Available online: https://kpmg.com/ie/en/home/insights/2025/02/csrd-sustainability-reporting-esg.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- GRI. A Short Introduction to the GRI Standards; GRI Standards: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/wtaf14tw/a-short-introduction-to-the-gri-standards.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- GRI. Get Started with Reporting; GRI Standards: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/public-policy/the-reporting-landscape/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Diez-Busto, E.; Sanchez-Ruiz, L.; Fernandez-Laviada, A. The B Corp Movement: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poponi, S.; Colantoni, A.; Cividino, S.R.; Mosconi, E.M. The Stakeholders’ Perspective within the B Corp Certification for a Circular Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, C. A foundation for ‘ethical capital’: The sustainability accounting standards board and integrated reporting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2024, 98, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudelaire, C. Fleurs du mal, L’Irréparable; Auguste Poulet-Malassis: Paris, France, 1857; Available online: https://fleursdumal.org/poem/149 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huston, S. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: An Ablative Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Climate Crisis via Conservative or Radical Reform Paradigms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114943

Huston S. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: An Ablative Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Climate Crisis via Conservative or Radical Reform Paradigms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114943

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuston, Simon. 2025. "Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: An Ablative Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Climate Crisis via Conservative or Radical Reform Paradigms" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114943

APA StyleHuston, S. (2025). Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: An Ablative Reflexive Thematic Analysis of Climate Crisis via Conservative or Radical Reform Paradigms. Sustainability, 17(11), 4943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114943