1. Introduction

According to the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034, global meat consumption is expected to grow by 47.9 million tonnes over the next decade. Global consumption of poultry, sheep meat, beef, and pork is projected to increase roughly 21%, 16%, 13%, and 5%, respectively, by 2034 [

1]. By then, poultry is expected to provide the largest share of protein from meat sources, accounting for 41%, followed by pig meat, beef, and sheep meat [

1]. Advances in breeding efficiency and slaughter yields are anticipated to help reduce the environmental footprint of meat production [

2].

Several studies emphasise that pig production has a lower carbon footprint per kilogram of meat compared to beef, primarily due to differences in feed conversion efficiency and metabolism between species. Despite this relative efficiency, the sheer volume of pork produced and consumed contributes significantly to total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) [

2]. Strategies such as improving feed efficiency, employing precision farming techniques, and utilising agricultural by-products in pig feeds are gaining attraction [

3].

Modern pig production is typically divided into three phases: gestation/farrowing, nursery, and grower/finisher. The grower/finisher phase, where pigs are fattened from about 30 kg to slaughter weight, is the most environmentally intensive due to prolonged feeding periods and high manure output [

4]. In addition to the farm level, significant environmental impacts, GHG emissions, water pollution, acidification, and energy use are primarily driven by feed production and manure management [

5]. Significant variation exists in the reported environmental impacts of pork production, often due to different feed conversion efficiency, system boundaries, functional units, geographical context, and production systems in use [

6]. At the farm level, environmental footprints also vary based on factors such as pig breed, production systems, slaughter age and weight, sex ratios, and the implementation of veterinary best practices. Röös et al. (2013) [

7] found that most environmental impacts in the pork supply chain occur on farms, with only about 12% stemming from post-farm activities such as processing, transportation, and retail. Feeds alone account for 55–75% of climate change effects, 70–90% of energy use, and up to 100% of land occupation in pig systems [

8]. Wu H et al. (2024) [

9] demonstrated that feed crop production and manure management contributed the most to the carbon footprint (54% and 22%, respectively) of 1 kg of pig live weight.

Soybean meals, a primary protein source in pig diets, are a major contributor to GHG emissions and land use impacts [

10]. European pig production relies on approximately 18.4 million tons of soy annually, mostly imported from Latin America, occupying nearly 14 million hectares of cropland [

10]. Soy cultivation is linked to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and biomass burning, contributing to anthropogenic climate change and atmospheric pollution, particularly in sensitive ecosystems [

11,

12]. These environmental concerns have driven the search for alternative protein sources that can reduce the carbon footprint of livestock production.

Several studies [

13,

14,

15] have demonstrated that the primary objective of using alternative feeds is to mitigate the environmental impact of livestock animals and reduce the feed costs associated with conventional feeds, thereby improving animal performance, representing a shift toward circular and eco-efficient feed systems that align with global sustainability goals. The transition toward utilising alternative proteins such as insect meals, plant-based ingredients, and innovative processing methods stands as a viable path to enhance sustainability and cost-effectiveness in pig nutrition [

16].

Substituting soybean meals with peas and rapeseed meals in grower–finisher pig diets led to reductions of 10% in energy use, 7% in global warming potential (GWP), and 17% in eutrophication [

14]. In a similar study by Eriksson et al. (2005) [

16], it was reported that replacing soybean meals with rapeseed meals and insects, especially black soldier fly larvae (BSFs), is another promising alternative because they offer high feed conversion efficiency, require minimal land and water, and emit fewer greenhouse gases than other insects. These are due to their significantly greater efficiency in converting feed into edible food than other animals [

17]. Furthermore, the lower space and water requirements for insect growth and development, along with their reduced contribution to GHG emissions, make them a sustainable and environmentally friendly protein source [

18].

However, the economic feasibility of these methods remains a challenge due to high production costs [

12,

19,

20]. Furthermore, feeding food waste, by-products, and residues to animals can play an important role in reducing the environmental impact of the food system by providing a sustainable alternative to landfill disposal or biogas production and to feed production [

21]. Historically, using food waste as pig feed has been a widespread practice across many countries for centuries. However, this practice was banned in the European Union in 2001 after the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom, which was linked to the illegal feeding of untreated food waste [

20]. Despite these limitations, there is a growing need to safely and correctly reuse food waste as animal feed within a circular economy framework, prioritising waste reduction and resource recovery along the supply chain [

19]. On the other hand, residues and by-products have also been studied for their potential to reduce feed costs and environmental impacts while maintaining nutritional adequacy. Given these findings, selecting low-impact feed and substituting soybeans with alternatives can significantly reduce the environmental and economic burdens of pig farming [

22].

Optimisation research addresses a variety of challenges, including minimising costs [

18,

23]. Cost minimisation problems are commonly tackled using linear programming (LP) methods, where an objective function is optimised under a set of linear constraints. This approach seeks the best possible solution, aiming to reduce costs to a minimum [

24]. Unlike single-objective models that focus solely on minimising total costs or maximising total profit, multi-objective linear programming (MOLP) models strive to optimise multiple goals simultaneously, balancing economic profitability with environmental sustainability [

23]. This study investigates the potential environmental benefits of replacing soybean meal with alternative ingredients in varying amounts in the diets of fattening pigs. The emphasis on fattening pigs is justified by the fact that they consume approximately 60% of the total feed used in the pig production chain and that they have a better capacity to utilise co-products compared to piglets and growing pigs [

25] The novelty of this work lies in its comprehensive approach, which utilises an environmental and cost minimisation approach [

17]. Therefore, the current work aims to broadly assess, rather than focus on specific ingredients, the environmental and economic impacts of incorporating both existing and novel co-products into pig diets in Europe, complementing existing studies on the environmental impacts of feed production.

This study incorporates a multistep methodology grounded in preliminary eco-design concepts to address the goal. First, a short narrative literature review was conducted to identify the substitute ingredients. Second, gradual substitution and optimisation using linear programming were employed to reduce the environmental and economic impact of a reference pig feed mix that could be used by pig-producing farmers. Third, a life cycle assessment (LCA) was conducted to evaluate the effects of each change and identify viable measures. It is essential to note that the current study represents a preliminary investigation aimed at demonstrating the potential of linear programming to support multi-objective optimisation in sustainable feed formulation. The nutritional adequacy and in vivo effects of the formulated feed require experimental validation and are outside the scope of this study.

3. Results and Discussion

This study identified 40 relevant publications between 2019 and the present. Among these, 19 are original research papers, while the remaining are literature reviews. Most studies focused on nutritional evaluations, rather than on commercial or field-scale applications. Of the 40 studies, 17 originate from non-EU countries, while the majority come from within the EU, reflecting a growing regional interest in sustainable feed alternatives. Among the 40 studies listed in

Table 1, 15 explicitly focus on BSF as an alternative protein source; therefore, this extensively researched ingredient was included in the list of soybean substitutes. Seven out of the forty articles address legumes as alternatives to soy, and in two of these, peas are explicitly discussed. For this reason, peas (P) have been introduced in the substitution and optimisation framework. Eight articles focus on residues and by-products; among these, bakery by-products—currently among the residues already used or usable in Europe—have therefore been identified as a third alternative to soy. In fact, among the alternative sources of animal feed, BP represents a particularly advantageous option, owing to its high palatability and substantial energy content. In addition, BP is free from common antinutritional factors—such as fibre, tannins, glucosinolates, and heat-labile trypsin inhibitors—and is consistently available on the market [

31]. Considering the 40 papers listed in

Table 1, only 11 studies addressed environmental aspects, and 13 considered economic implications, highlighting a relative underrepresentation of these dimensions. A significant portion of the literature employed comparative analyses, reinforcing their applicability to real-world decision-making contexts. In response to this research gap, eighteen diets were obtained using the approaches described in the Materials and Methods section. The overall ingredients and nutritional composition (see

Table 2) of the diets formulated through the gradual substitution of soybean ingredients (from 25% to 100%) while keeping NE constant, as well as the optimisation conducted to reduce the impact of climate change and costs while adhering to all imposed constraints, are reported in

Table 3. Substitution with BSF significantly increased costs (from 145 to 280%) while maintaining nutritional value in the 91–255% range of the “original” diets, as reported in

Table 4. This increase in cost is consistent with the literature. In their study, Siddiqui et al. (2025) [

69] found that the current price of insect meals is still higher than that of soybeans. When substituting soybeans with P or BP, a slight cost reduction (from 93% to 99%) was associated with fewer nutrients than the “original” (reduction from 69% to 99% and from 80% to 99% for BP and P, respectively). The resulting feed mixes, which included BP and P, had a lower digestible crude protein content per gram, which was linked to a reduced quantity of essential amino acids compared to the reference diet. Notably, all the diets obtained through substitution provided more essential amino acids than the recommended amount. Conversely, all the substitution diets had a lower amount of calcium than the recommended amount; however, the difference narrowed when introducing BSF, with BSF_100 providing 91.5% of the required calcium.

Following the optimisation approach, the introduction of BSF leads to increased costs (140% to 275%), while BP and P are associated with a slight decrease (from 91% to 95%). In the second case, all the nutritional parameters were satisfactory, although they were lower than those of the substitution diets. Again, only the amount of calcium fell below the recommended level, with BSF diets providing a more adequate amount of calcium. The BSF_100 diet exceeded 81% of the requirements, as shown in

Table 4.

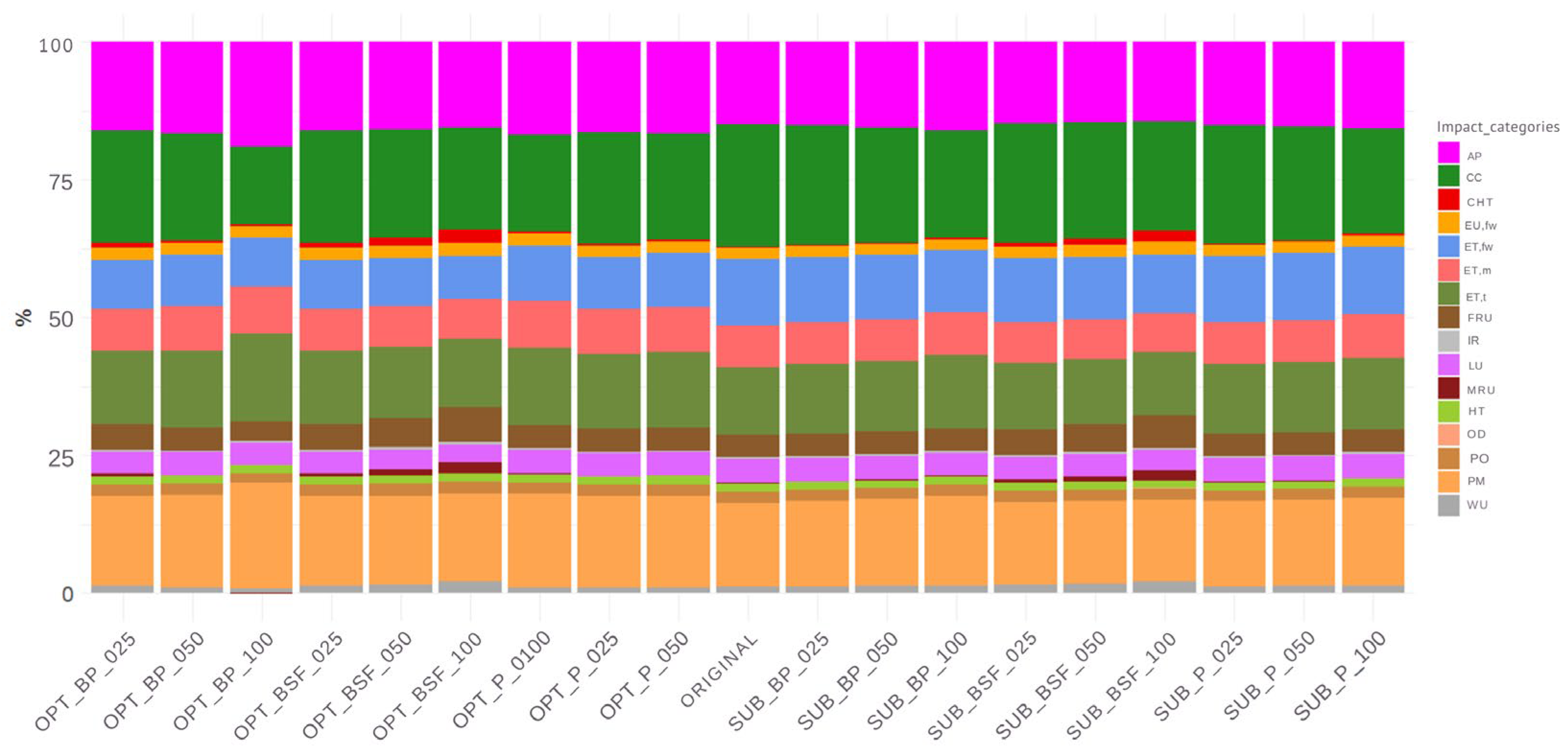

Table 5 presents the results of the selected impact categories for the 18 diets related to FU1. The impact categories were selected from the single score results (

Figure 1), including those that contributed more than 80% of the total single score results, excluding toxicity-related impact categories. Marine and freshwater eutrophication (EU,fw, EU,m, EU,t), freshwater ecotoxicity (ETfw), particulate matter (PM), acidification (AP), land use (LU), resource use (fossils) (FRU), and water use (WU) were also recorded

The target of reduced climate change impact was reached for all alternative feed mixes, with more significant reductions observed in the optimisation than in the substitution scenarios. However, substituting soybean-based ingredients with BSF had less favourable effects on marine, terrestrial, and freshwater eutrophication, acidification, particulate matter, water use, and fossil resource use, with an increase reported at every level of substitution, leading to higher single-score values in

Table 4 and

Table 5. In the substitution scenario, bakery by-products (BP) achieved the most substantial environmental targets at the 100% inclusion level, as BP_100 achieved significant reductions in both the single score and all the selected impact categories. The other scenarios with BP substitution, BP_25 and BP_50, resulted in an increase in water use and a reduction in all other impact categories. Pea diets also showed reductions at every level of substitution for all impact categories, except for water use, for which an increase was observed at every level of substitution. The reductions are greater for higher substitution percentages, although they are less significant than those obtained with BP. All alternative feed mixes showed reductions in most of the selected impact categories when the optimisation approach was applied. The only impact categories for which the optimisation approach led to an increase were resource use, fossils with BSF at every level, and water use and eutrophication freshwater using BSF at 50% and 100% inclusion levels. Moreover, the overall environmental single score results were lower than those of the baseline in all the optimisation scenarios, as shown in

Table 4. In the case of the optimisation scenarios, the P diets performed better than the BP diets at every level of optimisation and for all impact categories, except for land use and ecotoxicity in freshwater. However, for resource-use fossils, P_25 performed better than BP_25.

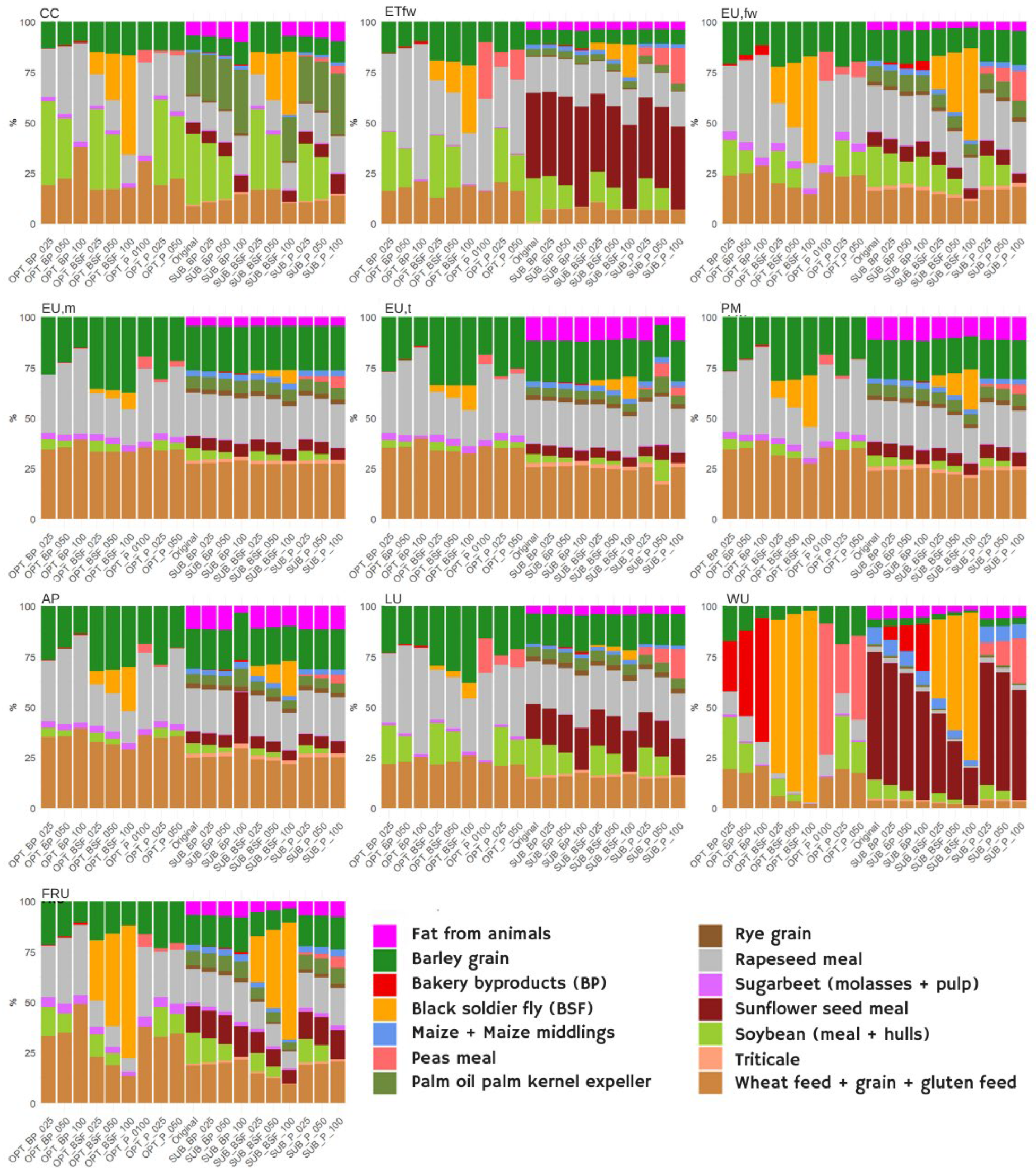

Figure 2 shows the contributions per impact category of feed ingredients for all diets. As soybean inclusion decreases through substitution or optimisation, its contribution to CC, ETfw, EU,fw, LU, and FRU impacts decreases, with the environmental burden shifting toward other ingredients. For climate change, the most impactful ingredients of the original diet are soybean meals and their derived ingredients, as well as palm-derived ingredients. In the substitution approach, when soybean ingredients are replaced with BSF, the reduction in the soybean contribution is offset by the contribution of BSF. When the other two alternative ingredients (BP and P) are used as substitutes for soybean-derived ingredients, their contribution is negligible; palm-derived ingredients and rapeseed meals are the primary contributors to the overall impact category. In the case of ecotoxicity, freshwater (ETfw), and water use (WU), the main impact was due to sunflower seed meals. This contribution remains significant in all substitution scenarios for ETfw, specifically in the BP and P substitutions for WU. Rapeseed meals, wheat-derived ingredients, and barley grain are the main contributors to EU,fw, EU,t, PM, AP, and FRU, while in the case of LU, sunflower seed meal is also relevant. The substitution scenarios do not result in a different distribution of impacts for those impact categories where soybean-based ingredients are not a significant factor. In the BSF substitution scenarios, BSF becomes one of the main contributors to ETfw and WU impacts, while for the other impact categories, the BSF contribution is negligible.

In the optimisation approach, the number of feed ingredients is reduced, with soybeans progressively being replaced and palm-derived ingredients being removed. Rapeseed meal, barley, and wheat-derived ingredients significantly contributed to all impact categories analysed, particularly at higher inclusion levels in the optimised BP and P diet scenarios. At the same time, BSF remained significant in CC, ETfw, EU,fw, LU, and FRU. Production suggested that while BSF is often utilised as a sustainable protein source, its production may be energy-intensive and involve environmental trade-offs. Similarly, palm oil and its derived ingredients exhibit significant climate-related impacts, underscoring the importance of a thorough evaluation of all alternative ingredients and their removal from the optimised scenario [

10]. A similar study [

9] was conducted, substituting soybean feed ingredients with feed processing by-products to effectively reduce the crude protein content of the feeds while ensuring the nutrient requirements for pigs’ growth. Their results have not found significant differences in the carbon footprints of all four scenarios developed, which were 1.68 kg CO

2-eq, 1.70 kg CO

2-eq, 1.67 kg CO

2-eq, and 1.68 kg CO

2-eq, respectively, for each kg of pig live weight at the farm. This similarity arises because maize is a significant contributor to the carbon footprint associated with feed crop cultivation, as highlighted by the significant environmental impact of this ingredient. In contrast, wheat bran contributes the least—ranging from 0.26% to 0.33%—due to its lower inclusion rate in the diet and a smaller allocation factor. Soybean contributes to 18% of the mass of feed in the fattening phase, while maize represents 72%, comprising a higher proportion of the total feed in the baseline scenario (in which soybean is not replaced), particularly because it is produced in China, with a higher use of chemical fertilisers in the crop production phase.

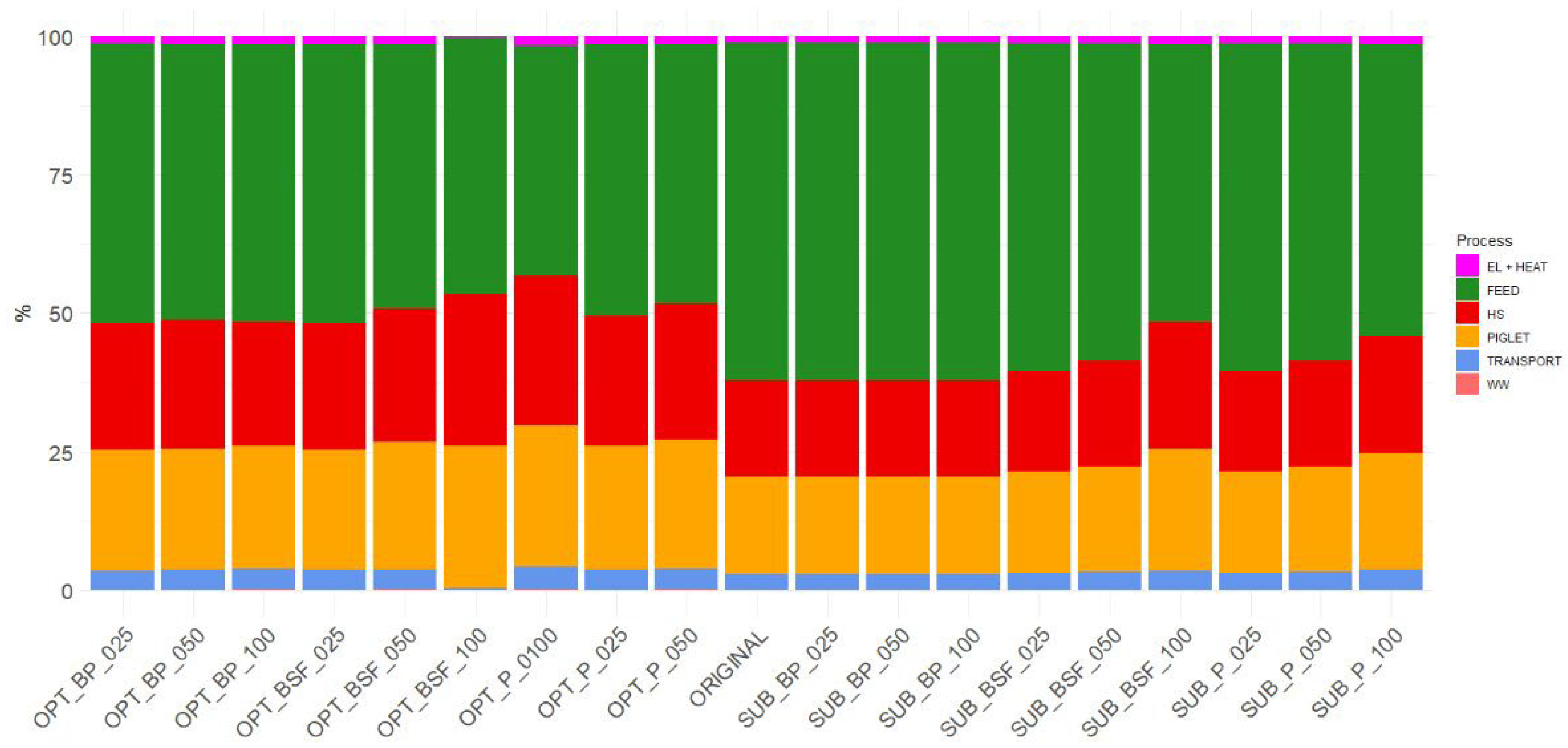

Figure 3 shows the primary processes that contribute to the overall single-score impact of the original diet and each alternative diet. Feed production is the primary process contributing to the overall impact, accounting for approximately 50% to 70%. The piglet production phase and housing systems contribute approximately 10% to 20% to the total cost. Electricity, heat, transport, and wastewater treatment contribute less than 5% of the overall impact. These results are consistent with those of Alba-Reyes et al. (2023) [

70], who identified feed production as the most environmentally impactful activity across all studied impact categories, contributing between 8% and 71% of the total, depending on the category. Similar results are reported by Dourmad and González-García [

71,

72], who identified feed crop cultivation as the primary source of carbon footprint, ranging from 60% to 80%. For crops such as corn and soybeans, the primary impacts of global warming result from field emissions and deforestation. Other previous studies support these findings. Noya et al. (2017) [

73] found that feed production in Spain is the most significant contributor (14–78%) to climate change and eutrophication, primarily driven using corn and soybeans as ingredients. Similarly, Groen et al. (2016) [

74] demonstrated that feed production can account for up to 67% of the environmental impact of pig production, primarily due to greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, pig feed is likely a significant contributor to most environmental burdens in pig farming.

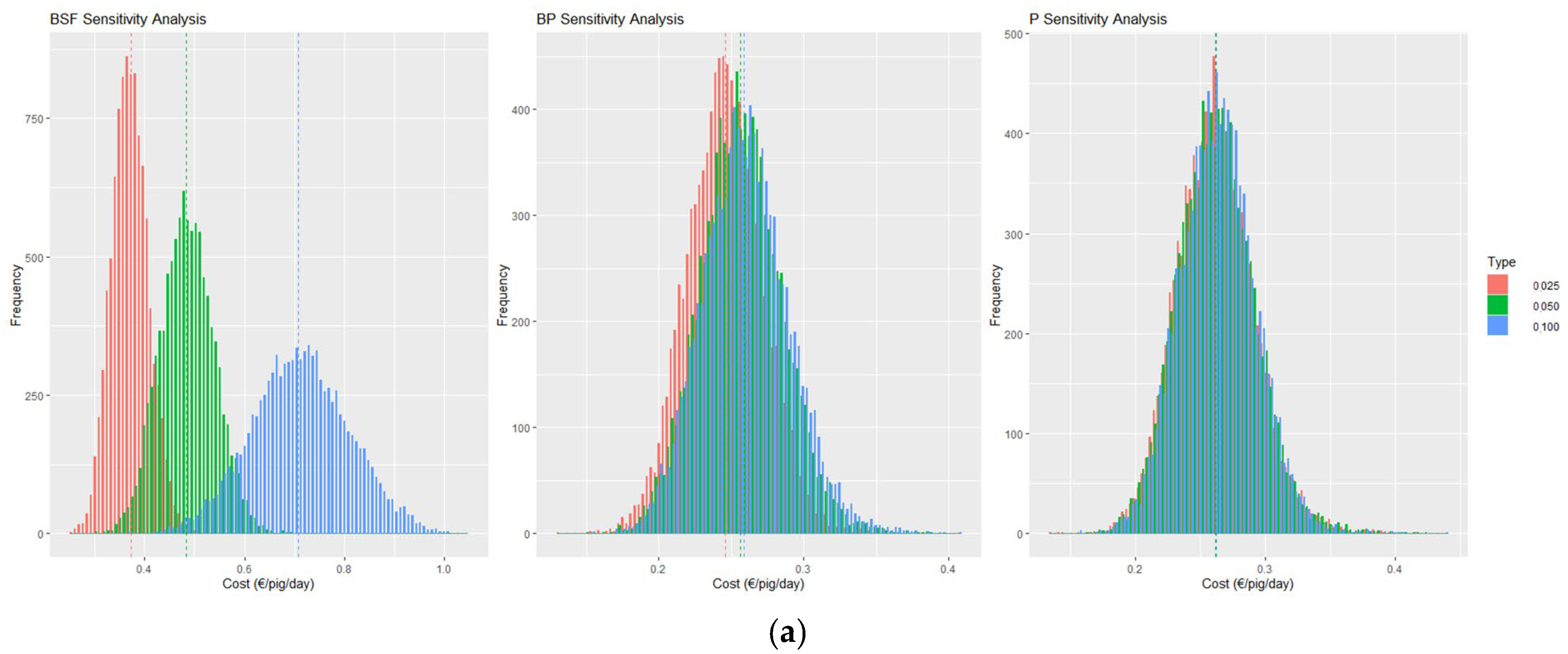

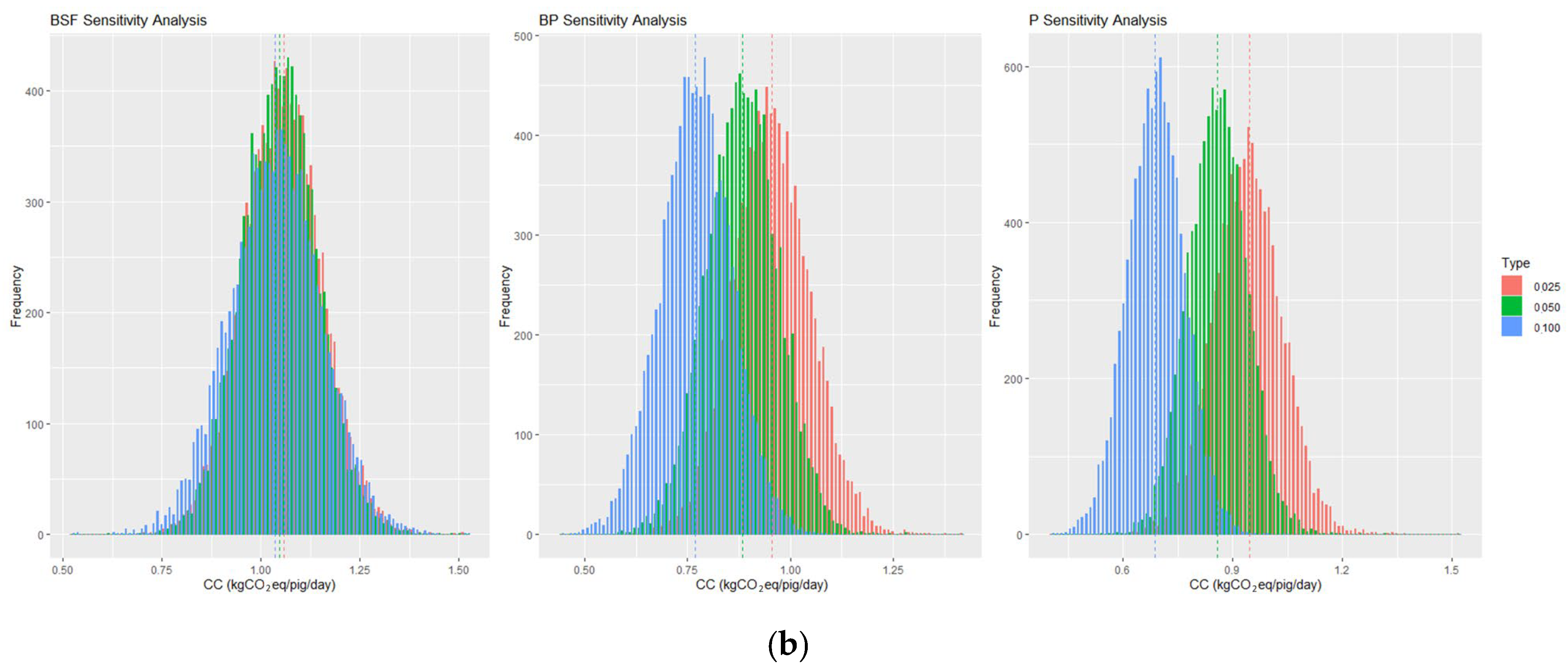

The cost sensitivity analysis is illustrated in

Figure 4a. Due to the highest cost of BSF, diet costs range from EUR 0.30 to EUR 0.45/pig/day, with a median of EUR 0.37/pig/day for the BSF_25 scenario; from EUR 0.38 to EUR 0.59/pig/day, with a median of EUR 0.48/pig/day for the BSF_50 scenario; and from EUR 0.52 to EUR 0.90/pig/day, with a median of EUR 0.71/pig/day for the BSF_100 scenario. As expected, the more BSF is incorporated into the diet, the higher the daily cost for feeding the pig. This trend is not observed in the BP and P scenarios, as the lower cost of the alternative protein ingredient does not significantly impact the overall cost of the diet. The climate change sensitivity analysis is illustrated in

Figure 4b. Due to the similar impact of BSF with soybean meals, all the BSF scenario distributions coincide, ranging from 0.86 to 1.26 kg CO

2 eq/pig/day, with a median value of 1.06, 1.05, and 1.03 kg CO

2 eq/day for 25, 50, and 100 scenarios, respectively. For BP scenarios, CC ranges from 0.59 to 1.14 kg CO

2 eq/pig/day, with a median value of 0.96, 0.88, and 0.77 kg CO

2 eq/pig/day for 25, 50, and 100 scenarios, respectively. Finally, for P scenarios, CC ranges from 0.53 to 1.13 kg CO

2 eq/pig/day, with a median value of 0.94, 0.86, and 0.69 for 25, 50, and 100 scenarios, respectively.

The impacts related to 1 kg of pig meat (FU2) are presented in

Table 6. In general, only the magnitude of the impacts of changes from introducing alternative feed mixes on the level of 1 kg of meat (FU2) was reduced compared to the impact modelled at 1 kg of feed (FU1), as those processes in the system between FU1 and FU2 were held constant. This is due to the consistency of downstream processes (e.g., housing and piglet rearing), which dilute the relative influence of feed changes. Among the alternative diets, those containing the bakery by-products BP and P had a lower overall environmental impact than the diets with full or partial inclusion of black soldier fly (BSF). Optimised diets demonstrate further reductions in impact or smaller increases compared to substitution diets due to a more sustainable balance between environmental performance and nutritional requirements.

When examining FU2 in the substitution scenario, bakery by-products (particularly BP_100) consistently demonstrated the most significant environmental benefits. BP_100 achieves a reduction in all impact categories, excluding water use, resulting in a 7% increase. Pea diets showed moderate improvement, with greater improvement at higher substitution rates (P_100). BSF-substituted diets showed only marginal improvements in climate change and ecotoxicity, as did freshwater and land use, while increases occurred in all the other impact categories. These increases are greater with higher inclusion levels.

The optimisation scenarios significantly improved the environmental impact across all the scenarios, except for the introduction of BSF to terrestrial eutrophication (increases in BSF_50 and BSF_100) and resource use (in all the BSF optimisation scenarios) impact categories. Overall, the optimisation and substitution scenarios demonstrated that bakery by-products and peas are the most environmentally sustainable alternatives to soybean meals, particularly when included through optimisation.

The advantages of using alternative ingredients have already been assessed in the literature. Stahn et al. (2023) [

75] investigated the use of brewer’s spent grain and agricultural residues from processed brewer’s capsules in pig feed formulations. Utilising these residues proved especially advantageous, as it reduces the need for conventional feed that could otherwise be used for human consumption. BSF-based feeds had no negative impact on meat quality, and the pigs remained healthy with weight gains comparable to those of pigs fed standard diets [

60]. Although the use of insects as feed is currently prohibited in the European Union (EU) under Regulation (EU) No 68/2013 when insects are reared on substrates containing manure or waste, it remains important to explore the potential of black soldier fly larvae to enhance productivity and resource use efficiency within the food system. Gasco et al. (2020) [

53] highlighted the potential of insects and fish by-products, which can partially replace conventional animal proteins while providing a sustainable nutrient profile conducive to livestock growth [

53]. The European Union supports this transition as part of its broader strategy to enhance protein self-sufficiency on the continent.

Pinotti et al. (2023) [

76] demonstrated that former food products could represent a valid option for strengthening resilience in animal nutrition. Among these ingredients, mainly leftovers from the bakery and confectionery industries, which are rich in sugars, oils, and starch, are explored as ideal alternative feed ingredients for pigs, as they can efficiently convert these ingredients into high-quality proteins. Ensuring the safety and quality of these feeds is crucial for animal and human health, requiring strict control over packaging residues and microbial contamination in line with regulations. The use of these ingredients in feed formulations supports a circular economy by reducing food waste and recycling nutrients back into the food chain as animal protein, resulting in other environmental benefits, including decreased landfill use, lower production costs, and a reduced environmental footprint of livestock and feed production [

21]. Several studies have explored the use of other alternative ingredients in pig diets. For example, Nguyen et al. (2024) [

28] investigated the impact of substituting soybean meal with poultry by-product meal (PBM) in grower–finisher pig diets, evaluating effects on feeding behaviour, growth performance, carcass yield, and meat quality. Their findings suggest that PBM can be a suitable primary protein source for growing–finishing pigs, as it did not adversely affect these parameters. Additionally, PBM could provide important nutrients such as calcium and phosphorus during this production stage. However, due to variability in the nutritional quality of PBM, it is crucial to analyse its composition before incorporating it into diets [

28]. Furthermore, comprehensive assessments of the environmental impacts related to PBM use remain lacking. It is also important to note that, at present, the use of such by-products in pig feed is prohibited in Europe. EU legislation emphasises feed safety and quality, ensuring that ingredients used in animal nutrition do not pose risks to animal health or food safety [

21]. Recent updates have focused on the permissible use of various animal by-products, highlighting the importance of managing these in a manner that supports both economic incentives for farmers and public health objectives, which restricts their practical application within this region [

28].

Few studies have utilised LCA to assess how food-forming products (FFPs) can mitigate the environmental impact of livestock production. According to zu Ermgassen et al. (2016) [

77], using food waste as pig feed could save 1.8 million hectares of agricultural land in the EU, a 21.5% reduction in land currently used for pork production, if used to replace 8.8 million tonnes of grains in pig diets. Vandermeersch and Salemdeeb [

78,

79] compared different food waste management options. The first study showed that the use of dry food waste (e.g., bread, pasta) is more effective at reducing environmental impacts across most life cycle assessment (LCA) categories. Similarly, the second concluded that using municipal food waste for animal feed results in lower greenhouse gas emissions and better environmental and health outcomes than composting or anaerobic digestion. The findings of this study align with and expand upon a growing body of literature not only regarding the use of residues but also about the introduction of other protein ingredients, such as peas, as substitutes for soybeans [

78,

79]. For example, Van Zanten (2014) [

25] demonstrated that replacing soybean meals with rapeseed meals and other co-products in pig diets significantly reduced global warming potential, land use, and energy demand. Similarly, Eriksson et al. (2005) [

16] reported that substituting soybeans with peas and rapeseed meal led to reductions of 10% in energy use, 7% in GWP, and 17% in eutrophication. The environmental impact of black soldier fly (BSF) meal is, however, multifaceted [

80]. While BSF is often promoted as a sustainable protein source due to its efficient feed conversion and low land use requirements, this study reveals significant trade-offs, particularly in water use and fossil resource utilisation. On the positive side, BSF larvae can significantly reduce organic waste volumes and are associated with lower greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane emissions, when compared to traditional composting or landfilling methods. Their ability to upcycle low-value waste into high-protein biomass contributes to circular economy goals and reduces reliance on resource-intensive protein sources like soy or fishmeal.

However, the environmental footprint of BSF production is not negligible; most LCAs, performed for cradle-to-gate boundaries, indicate that the production of the feeding substrate is the primary contributor to the global warming potential of insect production [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. Land use, eutrophication, and acidification are also predominantly attributable to the feed. Refs. [

84,

85,

86] have shown that BSF farming can be energy-intensive, especially during the breeding and processing stages, which may offset some of the climate benefits if not managed efficiently. These results are supported by the recent literature, including a 2024 commentary in

Nature, which acknowledges that although insect-based proteins can reduce land use by up to 96%, their production remains energy- and water-intensive [

87]. Additionally, in the present study, the inclusion of BSF at higher inclusion rates under substitution increased water use by +241.21% and fossil resource use by +93.04%, despite modest reductions in climate change impact. Under substitution, water use increased by +241.21%, and fossil resource use increased by +93.04%, despite modest reductions in climate change impact. Reckmann et al. (2016) [

87] assessed the environmental impacts of 16 pig diets across production stages using LCA, comparing standard feed with three alternatives: LOW (low-impact ingredients), LEG (high legume content), and AA (high synthetic amino acids). A scenario involving synthetic AA showed the lowest impacts due to reduced crude protein, which lowered nitrogen and methane emissions, suggesting amino acid supplementation can reduce the environmental footprint of pig diets. Stødkilde et al. (2023) [

29] investigated replacing imported protein sources with local alternatives like fava beans, rapeseed cake, and biorefined green protein. Feeding trials indicated that local proteins could maintain pig performance and pork quality while reducing the carbon footprint of feed (excluding land use change) from 543 g to 423 g CO

2-eq per kg. Further research is needed to evaluate the environmental impacts of green protein fully. Rebolledo-Leiva et al. (2024) [

24] analysed the environmental impacts of pig diets with a focus on reducing maize grain content, particularly using agricultural subproducts. Among the tested diets, Diet D1 was formulated with a notable reduction in maize, substituting it with low-impact subproducts while maintaining the same metabolisable energy as the control. Using both attributional and consequential LCA approaches, the study found that, from the attributional perspective, all alternative diets had lower environmental impacts per kilogram of feed compared to the control, with D1 showing the most significant improvements. When impacts were assessed per kilogram of weight gain, D1 still performed best overall, though not across all categories. The consequential LCA suggested that incorporating subproducts does not automatically yield environmental benefits, highlighting the importance of careful formulation and impact evaluation.

The current study does not specifically investigate individual nutritional differences among pigs. Previous research has shown that pigs exhibit consistent individual variations in feeding behaviour across time, characterised by four distinct dimensions. These behavioural differences extend beyond factors such as body weight and sex and are linked to other individual behavioural traits. While acknowledging individual differences is important, the current study focuses on a broader objective: understanding the overall potential for improving diet formulation without accounting for individual variability. Besides this, it could represent a limitation; this approach is necessary to provide a general assessment of how far feed optimisation can go in reducing environmental impacts.