1. Introduction

Every cultural manifestation unfolds within a physical environment adapted by humans into a social space. Consequently, culture and architecture are deeply intertwined, and investigating the traits of Andean rural architecture necessarily entails examining its cultural context [

1]. Rural architectural expressions materialize functional dynamics shaped by local demands, both residential and productive, and their form and organization are deeply influenced by the prevailing economic model [

2]. From a multidisciplinary perspective, this architecture is conceived as a complex cultural product whose dynamic and mutable character reflects a continuous process of transformation. Such transformation incorporates continual adjustments to shifting social and environmental conditions [

3]. Traditional constructions, in turn, provide substantial social benefits, including privacy, spatial hierarchy, family cohesion, and respect for cultural values [

4].

The spatial organization and elements of rural dwellings offer valuable insights into how societies regulated relationships among individuals, families, and the broader community. Specific architectural decisions—such as the arrangement of rooms, thresholds, and transitional areas—are closely tied to everyday social practices, shaping interactions both within the household and with the external environment [

5].

Within this framework, mediation spaces—understood as thresholds of encounter and transition between the private and the collective—play a pivotal role in social sustainability by facilitating community interaction and enabling appropriation of the built environment. Preserving these spaces allows existing structures to be reinterpreted in response to evolving social dynamics. Emergent through iterative, practice-based experimentation, these spaces are strategically oriented to buffer prevailing winds, temper solar exposure, and admit daylight, making them essential to sustainability.

These mediation spaces can therefore be read as strategic settings where memory, functionality, and social sustainability converge. It is therefore crucial to recognize and articulate them as catalysts within the social dimension of domestic architecture, due to the impact their morphology has on quality of life and social cohesion [

4]. Their study enables a critical examination of both cultural production and the material configuration of the surrounding environment [

6].

In southern Ecuador’s Andean context, rural homes operate as highly active and interactive organisms embedded in natural, built, and communal environments. They constitute a legacy not only of cultural identity but also of emotional support and familial cohesion, shaped significantly by economic and community activities [

7].

Today, the architectural production of rural housing reflects territorial dynamics characteristic of the Andean region. As Bebbington notes, Andean localities are embedded in global networks that reveal multiscalar relationships linking this territory to wider processes [

8].

These aforementioned processes affect rural architectural production and reveal challenges that threaten the continuity of building traditions: the use of local resources is increasingly supplanted by generic, industrialized materials, while traditional agricultural activities that once structured domestic space give way to new productive and architectural forms.

Simultaneously, internal and external migration reshapes territorial geographies and residential occupancy patterns, eroding community ties. Comparative data from the 2010 and 2022 national censuses (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos del Ecuador INEC) for the province of Loja show a 40% increase in rural-to-urban migration (approximately 13,000 people) and a 50% increase in migration outside the province (about 6000 people) [

9].

As a collateral effect, many rural homes are abandoned—accelerating deterioration—while new architectural models are introduced that fail to respond to topography and local climate, disrupting the agricultural landscape that characterizes Andean rurality. Many such structures disregard the defining features of traditional housing, forcing customary activities into spaces ill-suited to them.

In light of this aforementioned context, a focused inquiry into Andean rural architecture is imperative—one that prioritizes components offering actionable resources for rethinking design practices in remote and marginalized areas [

10].

This study examines the rural architecture of Loja Province, in the southern Ecuadorian Andes, not merely as a collection of material forms but as the expression of a dynamic cultural process shaped by everyday dwelling practices and by their relations with environmental and social contexts. Rather than conserving “authentic” forms or advancing heritage-designation strategies, this article aims to demonstrate how domestic architectures can function as active devices of social sustainability, sustaining resilient, inclusive, and place-based ways of life. Specifically, the study (i) investigates the role of interior–exterior mediation spaces (portals, hallways, patios, corridors, basements, and soberados—over-portal attics) in sustaining social cohesion and everyday livelihoods; (ii) examines how their morphology and use vary across Loja’s ecological belts; and (iii) assesses their contribution to intergenerational knowledge transmission and adaptive capacity.

This aforementioned perspective remains underexplored. Although interest in vernacular housing has grown in recent decades—especially for its heritage value and the preservation of traditional construction techniques—research addressing the impact of these architectures on social cohesion, intergenerational knowledge transmission, and adaptability to new conditions is still limited. Recent studies, however, have begun to recognize the transformative potential of vernacular dwelling practices, showing how they can operate as platforms for community resilience and social sustainability, particularly in rural contexts across Latin America, Asia, and Africa [

11,

12].

In Ecuador, several works have highlighted the value of local construction know-how and its environmental integration—for example, the role of natural lighting in traditional dwellings [

13] and design strategies to improve climatic adaptation in Andean courtyard houses [

14]. Beyond material performance, the emerging literature underscores vernacular architectures as dynamic engagements with the environment capable of innovation through everyday practices [

15,

16,

17].

Research on Indigenous communities adds crucial socio-cultural depth. Larrea [

18] examines community organization grounded in mutual aid, territorial attachment, and resilience amid structural exclusion; the INPC has documented rich intangible heritage—worldviews, oral traditions, rituals, festivities, and communal practices—that sustains identity, cohesion, and intergenerational transmission [

19]. This heritage fosters identity, social cohesion, and respect for nature, but it is also linked to collective memory and intergenerational transmission [

20,

21].

Meanwhile, Catalina Campo [

22] traces Ecuadorian anthropology’s engagements with Indigenous knowledge, intercultural education, and resistance to extractivism, offering a critical, ecological, and ontological perspective. While these strands illuminate environmental performance and cultural frameworks, there remains a gap regarding how domestic spatial mediations concretely sustain social sustainability in everyday use. This study addresses that gap.

To address the research aim, we adopt a mixed-methods design that interlaces spatial analysis with ethnographic inquiry to examine how tangible and intangible elements of rural housing sustain one another and contribute to situated, sustainable dwelling practices. This perspective captures not only the physical dimension of the rural house but also the symbolic, functional, and affective ties that shape its use, persistence, and transformation. In this regard, rural architecture emerges as a fertile domain for studying social sustainability beyond normative frameworks—through the lived experiences of those who inhabit, modify, and continually reinvent their spaces.

1.1. Framing Social Sustainability in Rural Architecture

A broad body of scholarship shows that the morphology of traditional dwellings across the world does not respond solely to functional demands; it also plays an active role in preserving and transmitting communities’ socioculturalism [

5,

20]. Accordingly, it is essential to clarify the social and cultural sustainability criteria embodied in this architecture—particularly with reference to Andean rural housing in southern Ecuador. As a situated practice, architecture shapes sustainable development not only through technical performance but also through its capacity to sustain ways of life and social relations [

23].

Despite the growing body of literature on concepts such as social capital, community cohesion, and social inclusion or exclusion, research specifically addressing social sustainability within the field of vernacular architecture remains limited [

24]. In both academic and policy arenas, there is broad recognition that the quality of the built environment, sense of community, and social participation are vital to collective life; yet systematic tools for evaluating these factors in rural contexts are still scarce.

Recent contributions propose methodologies rooted in human-centered design, placing human–environment interaction at the core in order to identify social and cultural sustainability criteria applicable to vernacular settings [

25,

26]. Much of this work, however, remains oriented toward heritage conservation, construing cultural and social sustainability primarily as the active inclusion of communities in preservation processes. From this standpoint, cultural sustainability has been interpreted expansively—to include the transformability of architectural forms, the incorporation of environmentally responsible design strategies, the use of digital tools for documenting and safeguarding heritage, and the direct participation of local communities—while social sustainability is linked to strengthening social ties and fostering collective engagement [

27]. Preserving vernacular architecture therefore entails not only conserving material fabric but also sustaining the social and cultural practices that animate it.

This study foregrounds the adaptability of these architectures to social and environmental change in rural territories, thereby extending a narrowly heritage-focused lens. Here, the building is approached not as a fixed, static object but as an active, transformable entity that responds to shifting conditions. In this light, the dwelling is understood as an infrastructure for inhabitation [

28], that is, an organism capable of supporting multiple functions and reconfiguring itself in response to external needs. Both rural labor and the spaces in which it occurs evolve continuously; such transformation does not simply replace the old with the new but generates novelty from what already exists [

29].

Beyond adaptability, we integrate additional criteria to assess social sustainability in rural architecture: functional flexibility (the capacity to reuse or reinterpret spaces without major alterations); intergenerational knowledge transmission (the continuity and evolution of traditional know-how); community participation (active involvement in the production and management of space); inclusion and coexistence (the accommodation of diverse social groups); and perceptual and emotional well-being (the symbolic and affective dimensions of dwelling). Considered together, these indicators provide a nuanced, contemporary understanding of vernacular architecture as a foundation for socially and culturally sustainable practices deeply rooted in place.

1.2. Contextual Framework: Typological Genealogy of Rural Housing in Southern Ecuador

The analysis of rural dwellings in southern Ecuador requires an explicit engagement with the concept of architectural typology. De Carlo’s [

30] definition of type was adopted as the set of codes that deciphers architecture’s communicative system. In a region shaped by pronounced cultural hybridity, typological investigation becomes indispensable for tracing the layered influences that have shaped the Andean house.

Rather than serving as a purely taxonomic exercise, typological inquiry is here employed as a generative tool, aimed at extracting design principles suitable for critical reinterpretation in contemporary practice [

21]. This position aligns with the genealogical studies of earthen vernaculars developed by Oliver [

31,

32], Fathy [

33], and CRATerre [

34], which underscore the socio-environmental foundations of vernacular form. By establishing resonances across apparently dissimilar artifacts, the method foregrounds accumulated spatial memory and situates local production within broader discourses of earthen architecture [

35]. Three analytical systems—spatial, physical, and stylistic—are therefore distinguished. Acting semi-autonomously, they explain how houses sharing identical volumetric configurations can exhibit divergent material solutions, ranging from adobe and tapial masonry to lightweight bahareque envelopes. Building on regional historiography [

36,

37], three major genealogical strands are identified as follows:

Hacienda House: Originating from the land grants (“mercedes de tierras”) issued during the colonial period by regional courts and viceroyalties for agricultural, livestock, or mining purposes [

38]. Studies by Aguirre-Ullauri [

38] and Sánchez [

39] provide a detailed architectural analysis of the haciendas of Shuracpamba and El Paso, located in the neighboring Azuay region. These estates were typically organized into clusters of buildings, including a main house with a regular floor plan (L-, C-, or H-shaped) accompanied by secondary structures such as chapels, sometimes churches, hospitals, workers’ housing, storage buildings, and production spaces adapted to local crops, like sugarcane below 1400 m above sea level. A distinctive feature is the deep portal that wraps around the main building, creating a habitable space that enables visual control over the complex and the surrounding landscape.

Andalusian House: A colonial typology primarily defined by a central courtyard layout and continuous facades marked by ornamental windows and doorframes. From a construction standpoint, the use of stone plinths and rammed earth techniques were fundamental in providing durability and strength to local buildings [

40].

Qullqa House: A Quechua term referring to storage space, reflecting its strong connection to agricultural practices. These small-scale dwellings typically consist of a single multifunctional room and a loft accessed via wooden stairs, used for storing food or tools, with ceiling heights ranging from 3.50 to 4.00 m. Oriented from east to west to maximize solar gain, they integrate domestic and productive functions within a shared space.

Building on this typological palimpsest and the foregoing discussion of social sustainability, we advance the notion of living architecture: an architecture conceived as a socio-spatial system that adapts through everyday use, collective participation, and the calibrated deployment of locally available resources while sustaining cultural continuity. Within this framework, intermediate spaces—portales, zaguanes, patios, and corridors—are theorized as relational thresholds that function as the dwelling’s “vital organs”, mediating exchanges between interior and exterior and between domestic and communal realms. Our empirical analysis tests the performative capacity of these mediating organs and shows that, by hosting productive, ritual, and social practices, they catalyze social cohesion, intergenerational knowledge transmission, inclusion, household micro-economies, and place-based well-being—core components of social sustainability. Methodologically, the study operationalizes the concepts of reversible thresholds and constructive metabolism articulated in evolutionary approaches to the conservation of earthen architecture, providing criteria for acceptable transformation that safeguard cultural values and inform adaptive reuse in rapidly changing rural contexts [

41].

A detailed examination of these interstitial domains not only elucidates historical sustainability strategies but also provides a basis for contemporary design responses to climatic resilience, social cohesion, and cultural continuity. Hence, this research interrogates how mediating spaces can sustain community life amid ongoing architectural and cultural transformation, offering an integrated reading of Andean housing that recognizes its symbolic charge, performative capacity, and future-oriented design potential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

This study combines qualitative and quantitative approaches within a mixed-methods design, with strong ethnographic and design-based components. Recognizing that architecture extends beyond built objects to encompass ways of dwelling, spatial production, and transformation across social, material, and symbolic domains, our methodological aim was to construct a technical perspective grounded in the rural Andean architectures of southern Ecuador, integrating tools from design, ethnography, and spatial analysis.

The research adopts an inductive, critical stance responsive to the complexity of the phenomena under investigation. As Groat and Wang argue, architectural research must be capable of “addressing both the understanding and the creation of the built environment”, and therefore requires flexible methodological frameworks that bring together diverse forms of knowledge [

42]. In this sense, the study does not seek to establish normative models but rather to create a space for reflection on the relationships among architecture, territory, and everyday life.

An initial phase involved the collection and critical review of specialized literature to construct a theoretical framework guiding subsequent fieldwork. Next, an extensive empirical investigation was conducted based on in situ observations in various localities of the Loja province. The selection of this area was motivated by its distinctive territorial characteristics: on one hand, the diversity of landscapes, climates, and physical-environmental conditions; on the other, the presence of populations belonging to different ethnic groups whose cultural practices, customs, and dwelling patterns vary significantly. Selecting case studies located in diverse physical, environmental, and social contexts responds to the aim of examining how housing typologies are shaped by multiple factors.

Fieldwork comprised systematic scheduled visits, photographic and audiovisual documentation, and semi-structured interviews with inhabitants.

First, the field campaigns enabled the identification and systematic documentation of 250 buildings, each photographed and recorded. From this inventory, 35 representative cases were selected for in-depth analysis. Given the high density and diversity of rural architectural expressions in the study area, case selection was conducted via simple random sampling, including only those dwellings that met the typological criteria defined by Hermida and Mogrovejo (2015) [

43]. This approach ensured that the sample faithfully reflected the region’s traditional housing typologies.

To capture seasonal variation in use—particularly linked to agricultural cycles—each dwelling was visited at least twice, and most were visited three times. To support comparability across cases, we developed a standardized analytical recording sheet, detailed in the following section.

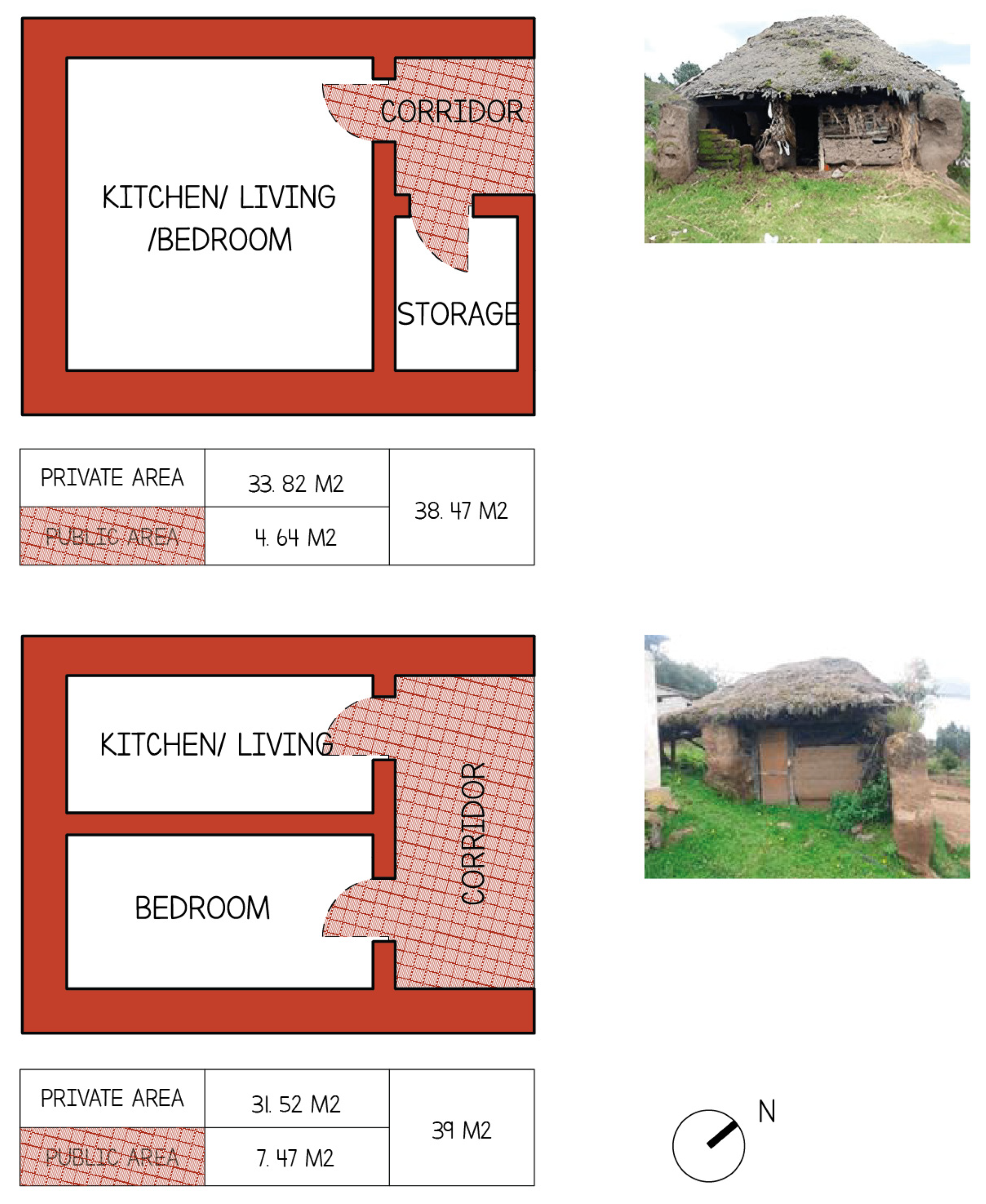

The transition from the initial field photographs—such as those shown in

Figure 1 to the analytical drawings involved an interpretive and abstracting process designed to place the human figure at the center of the represented architectural scene as an active subject. In contrast to conventional technical drawings, which tend to suppress the specificity of human presence, our representations deliberately reinsert strongly characterized figures. In doing so, the study counters the homogenization typical of architectural drawing—where physical and cultural traits (e.g., attire, everyday objects) are often standardized to foreground technical aspects—and instead integrates the ethnographic dimension not only during documentation but also within the final graphic outputs.

All architectural data were systematized and redrawn in AutoCAD 2018, then post-processed in Adobe Illustrator 2022 to produce analytical graphic representations (plans, sections, axonometries, and functional diagrams). These visuals were essential for interpreting the data from both spatial and social perspectives, linking the quantitative dimensions of morphological analysis with qualitative insights derived from direct observation and ethnographic recording. Throughout, architectural drawing functioned as a central research instrument—both for inquiry and for the communication of findings—situating the study within a research-by-design framework in which drawing operates as a medium for knowledge production.

Given the socio-spatial orientation of the study, particular attention was devoted to documenting dwelling practices: daily uses, interior routes, and dynamics of spatial appropriation by inhabitants. The integration of these tools enabled a comprehensive perspective on rural housing, attentive to its embeddedness within a changing landscape and to its adaptive capacity in the face of contemporary dynamics such as migration, territorial fragmentation, and the expansion of extractive logics. Accordingly, the methodology embraces a situated form of knowledge production that weaves together design thinking, lived experience, and territorial analysis.

The following sections detail the specific procedures adopted, emphasizing two principal approaches: (1) analysis of the spatial configuration of traditional rural housing (research-by-design) and (2) observation of dwelling practices that underpin its social sustainability. In combination, these perspectives clarify how sociocultural dynamics have influenced the morphological diversity of these architectures, integrating quantifiable evidence with interpretations attuned to lived contexts.

2.2. Research by Design

The design-based research methodology was structured around analytical observation, serving as the foundation for an in-depth study of these dwellings. This approach enabled the identification of the distinctive features of the Andean housing typology, enriching existing classifications and establishing connections with previous typological studies.

To develop a comprehensive understanding of the architecture and its determinants, we conducted a multiscalar spatial analysis that examined the relationships between rural dwellings and their physical settings and the internal architectural organization of the house, including the material resources employed in construction. Drawing was deployed not only as a representational tool but also as a research instrument capable of exploring trans-scalar relationships and multiple representational modes. In this sense, drawing is positioned as the primary investigative device, as it encourages non-linear, counterintuitive thinking [

44]. Research-by-design is thus an appropriate strategy for addressing the complexity of a transforming rural context marked by heterogeneous situations. Given this diversity, drawing facilitated creative leaps and the generation of associations among spaces, actors, and contexts that might otherwise remain concealed. Accordingly, design-based inquiry entailed the exploration of strategies, procedures, methods, trajectories, tactics, schemas, and modes through which inhabitants creatively interact with their territory [

41].

To document the most relevant architectural information for the 35 selected cases, we adopted a data recording sheet as a systematic tool for collection and subsequent comparison. The sheet (presented in

Figure 2) records key constructive and typological parameters of each dwelling, along with uses, integrated systems, and current state of conservation. In addition, axonometric, plan, and elevation drawings are included to fully capture the building’s morphology; the history of the dwelling—as recounted by its owners—is also registered. Finally, the sheet incorporates a brief photographic log of each case. This instrument was developed by the authors on the basis of the template used by Ecuador’s Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural (INPC) and was enriched with additional fields and dedicated spaces for graphic representations.

As Nova observes, behind every architectural configuration lies, potentially, an anthropological question about how an individual or a community inhabits—or wishes to inhabit—the world, and with it an opportunity to contribute to knowledge about the act of designing [

45]. It is therefore essential to complement spatial analysis with an ethnographic approach oriented toward understanding the dwelling practices enacted within the studied spaces.

Positionality and fieldwork procedures. We recognize the importance of positionality and reflexivity in ethnographic inquiry. The first author—an architect and academic based in Ecuador for over a decade—has conducted extensive fieldwork in rural areas of the country, establishing long-term professional and research relationships. The second author, originally from Ecuador, has a longstanding trajectory of engagement with Andean communities, focusing on vernacular architecture and local construction practices. Although neither author comes directly from the communities studied, both maintain close familiarity with their cultural and spatial contexts. Fieldwork was conducted in Spanish, the common language of the region, though some terms used by residents derive from Kichwa and were interpreted in context; all participants are fluent in Spanish. To ensure ethical rigor, all participants provided informed consent, and the research protocol was approved by the UTPL University Ethics Committee. Both authors engaged in ongoing reflexive journaling to identify and mitigate personal biases arising from their academic and cultural backgrounds.

To address gender and generational representation, interviews and participant observations included individuals of varied ages, genders, and occupations. Local collaborators—such as community liaisons and Kichwa-familiar translators—supported the work, enhancing cultural interpretation and facilitating access. To capture seasonal dynamics that shape spatial use—especially in relation to agricultural cycles (planting/harvest)—each house was visited at least twice over the year, and most were visited three times. Data from multiple sources (interviews, visual documentation, and spatial drawings) were triangulated to strengthen the credibility and richness of the findings.

2.3. Ethnographic Exploration

Ethnographic exploration was essential to understand the social, symbolic, and emotional dimensions that structure ways of inhabiting space. This approach rests on an expanded conception of architecture—not only as a material practice but also as a cultural and relational phenomenon. As Albrow notes, ethnography in global contexts enables the capture of multiple scales of social processes and local dwelling practices without reverting to determinism or cultural idealization [

46].

In this study, the ethnographic lens responds to a call for greater realism in socio-spatial observation [

47] and supplies conceptual and operational tools to bridge deliberate architectural discourse with the operative knowledge of residents, particularly in settings shaped by overlapping influences and traditions.

Fieldwork combined semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and audiovisual documentation. We conducted 35 semi-structured interviews with household members across the three study zones, using purposive sampling to maximize variation in climatic setting, construction system, household composition, and length of residence. Recruitment was supported by local community liaisons. Interviews were carried out in Spanish (with occasional Kichwa terms) by the first author between June 2022 and August 2023, lasted 45–90 min, and were audio-recorded with written informed consent under ethics approval from University UTPL.

An interview guide, developed following Kvale & Brinkmann [

48], combined “grand-tour” prompts—broad, open requests inviting participants to lead us through a

typical day and a

walk-through of the house—with mini-tours and focused probes on intermediate spaces (portal, hallway, patio), their seasonal uses, and micro-transformations associated with domestic, ritual, and productive practices. The goal was to obtain a holistic picture that reconstructs the processual and ritual character of everyday actions within domestic space. The full guide is provided in

Appendix A.1. During and after each visit, we produced fieldnotes and contextual photographs/video, enriching interview data through participant observation of the dwelling and its immediate surroundings [

49]. Transcripts were anonymized and thematically analyzed [

50] through iterative coding cycles: open coding, constant comparison, and theme consolidation. Two researchers cross-checked 25% of the transcripts to enhance credibility; disagreements were resolved through discussion. Data adequacy was assessed against both code saturation and meaning saturation [

51]. Finally, interview evidence was triangulated with architectural survey drawings and on-site observations [

52], allowing us to connect stated practices with spatial configurations and material details. In addition, five interviewees consented to semi-structured video recordings describing daily life and the use of domestic space; this audiovisual material informed a short informational film produced in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural (INPC) of Ecuador (

Appendix A.2). Where relevant, illustrative anonymized excerpts are reported in the Results section to make analytic claims traceable.

Beyond housing data, this work documented family histories, migratory trajectories, construction knowledge, and affective ties to territory. These dimensions—often absent from conventional architectural studies—proved critical for understanding rural housing not as a static unit but as an assemblage of spatial, social, and symbolic relations in continuous transformation.

To reflect these insights, architectural representations explicitly incorporated the human figure and its actions: diurnal patterns of use, movements within the house, and everyday and ritual objects that characterize domestic environments. The graphic work sought to construct an ethnographic survey that consistently integrates territorial, architectural, and human scales, portraying an inhabited environment in dynamic equilibrium.

The ethnographic approach adopted here was inspired by a “proximity ethnography”, in which the relationship between researcher and participants is not based on analytical distance but on the establishment of mutual trust. This methodological attitude enables access to the intangible aspects of dwelling—such as rituals, everyday practices, or spatial perceptions—which are fundamental for constructing situated and sensitive knowledge. As Sarah Pink [

53] observes, visual and sensory methods allow researchers to approach spatial experiences from the perspective of those who live them, thereby generating a richer and more complex understanding of the built environment.

Positionality and ethics. We acknowledge the importance of positionality and reflexivity in ethnographic inquiry. The first author—an architect and academic based in Ecuador for more than a decade—has conducted extensive fieldwork in rural areas, maintaining long-term professional and research relationships. The second author, originally from Ecuador, has a longstanding engagement with Andean communities focused on vernacular architecture and local construction practices. Although neither author belongs directly to the communities studied, both are closely familiar with their cultural and spatial contexts. Fieldwork was conducted in Spanish, the region’s common language; some locally used terms derive from Kichwa and were interpreted in context, as all participants were fluent in Spanish. Ethical rigor was ensured through informed-consent procedures approved by the UTPL University Ethics Committee. Both authors kept reflexive field journals to identify and mitigate potential biases arising from their academic and cultural backgrounds.

To address gender and generational representation, interviews and participant observations included people of different ages, genders, and occupations. Local collaborators—community liaisons and translators familiar with Kichwa—supported cultural interpretation and facilitated access.

Finally, to capture seasonal dynamics that shape spatial use—particularly those linked to agricultural cycles of planting and harvesting—each dwelling was visited at least twice over the year, and most were visited three times. Information from multiple data sources (interviews, visual documentation, and spatial drawings) was triangulated to enhance the credibility and depth of the empirical base.

2.4. Study Area and Case Study

The province of Loja, on the border with southern Peru, presents a complex geography defined by a pronounced depression in the Real cordillera and the Andean foothills. Altitudinal variation from 200 to 3700 m a.s.l. generates marked ecological diversity in climate, vegetation, and resource access [

54,

55]. The Catamayo basin channels warm, dry air from the southern desert for much of the year, contributing to persistent desertification in the west and southwest of the province [

56].

According to 2024 projections by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), Loja has 537,000 inhabitants, 44.2% of whom reside in rural parishes [

9]. Rural density (38 inhabitants·km

−2) is well below the national average (59 inhabitants·km

−2), reflecting dispersed settlement patterns shaped by topography and land tenure. Socio-economically, 31.4% of residents live below the national poverty line and 12.8% in extreme poverty, placing Loja fifth among Ecuadorian provinces with the highest rural inequality (Gini = 0.769). Agriculture remains the dominant sector: in 2023, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG) reported 92,600 ha under cultivation; maize (34%), beans (15%), and coffee (13%) accounted for 62% of total output, and 4469 smallholders were enrolled in the public crop-insurance scheme [

57].

Climatically, Loja spans humid tropical conditions in the inter-Andean valleys (~1600 m a.s.l.), temperate in the Andean corridor (2525 m a.s.l), and dry to semi-arid conditions in Zapotillo (~223 m a.s.l.), producing a sequence of sharply differentiated environmental units. The border zone with Peru is characterized by dry forest and terrain descending toward the Peruvian desert. This environmental heterogeneity has decisively shaped rural settlement patterns and construction strategies adapted to local conditions.

Across the province, a relatively homogeneous material palette—stone, timber, and earth—aligns with vernacular logics of building with locally available resources. Techniques, however, vary with climate. In warm areas, where the priority is to dissipate internal heat gains, lightweight, narrow-section solutions predominate, notably bahareque (wattle and daub) walls that enhance cross-ventilation and passive cooling. In temperate and cold zones, the emphasis shifts to heat retention; massive adobe and tapial systems are favored for their high thermal inertia, storing energy during the day and releasing it gradually at night. Using the same materials, vernacular dwellings thus deploy differentiated strategies that optimize hygro-thermal comfort and exhibit strong adaptive capacity. Spatially, adobe/tapial construction correlates with higher elevations (>1500 m) and lower rural density: in cantons such as Saraguro (19 inhabitants·km

−2) and Quilanga (22 inhabitants·km

−2), 73% of extant houses have massive earthen walls, whereas in the drier lowlands of Zapotillo (47 inhabitants·km

−2), lightweight bahareque represents 68% of the surveyed stock [

58].

For this study, three macro-zones were defined (

Figure 3): Sector A—temperate mountain interfluves in the central–northern region; Sector B—the humid eastern slope transitioning to the Amazon basin; and Sector C—dry valleys in the southwestern border area with Peru. These areas exhibit distinct altitudinal, topographic, and climatic conditions; examining them comparatively allows us to trace how dwelling typologies vary across contrasting contexts. The climatic range follows the Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial (2022), which classifies the province into three macroclimates by intersecting isotherms with elevation.

Among the three sectors, Saraguro (Sector A) is distinguished by a dense calendar of communal and ritual practices that intensify the everyday use of portals and thresholds. Fieldwork in this sector was conducted through culturally sensitive protocols and collaboration with local authorities and community liaisons to align visits with ritual schedules and ensure informed consent.

Each sector displays specific settlement patterns and domestic typologies shaped by physical–environmental conditions and differentiated historical trajectories. Rural architecture in Loja can therefore be understood as a situated assemblage of spatial expressions that integrate geography, collective memory, and productive practices. Historically, dwellings were built from local materials in dialogue with the landscape; colonial occupation introduced new construction logics and land-use patterns, producing hybrid forms in which Indigenous and colonial elements coexist [

59]. Over the twentieth century, migration, land parceling, and the diffusion of urban models progressively transformed the rural habitat; today, extractivism, regional mobility, and the revaluation of local heritage further reshape these dynamics [

60].

As highlighted in recent studies [

13,

17,

61], the specificity of Loja’s vernacular architecture lies not only in its materials and techniques but in its capacity to mediate between everyday life and the natural environment, integrating agricultural, ritual, and relational practices within the built space. This characteristic gives the dwellings a processual quality, open to transformation, where architectural elements act as thresholds between the domestic, productive, and symbolic realms.

This research analyzes the case study through a critical lens, challenging traditional notions of rural architecture and heritage. It distances itself from folklorizing perspectives and instead proposes an approach attentive to the material, social, and ecological conditions that shape Andean dwelling. Due to its unique convergence of geography, history, and culture, this territory provides essential insights for rethinking the resilience and agency of rural communities in the face of contemporary challenges.

3. Results

The morphological study of the dwellings clarified the geometric and volumetric features of the rural architectures analyzed, as well as the organization of solids and voids in plan and elevation. Consistent with previous research, we confirm a notable spatial regularity marked by a sequence of rooms arranged in a linear progression [

43]. The façades display an alternation of foreground and background volumes whose cadence follows the underlying structural regularity of the buildings. Topography directly informs this arrangement: houses are typically sited without leveling the natural terrain, which produces either disarticulated bodies or the use of a raised plinth that mediates between the building and the ground.

Beyond form, the analysis examined structure, materiality, and spatial layout in relation to everyday dwelling practices that sustain and re-signify architecture over time. A key finding is the relative typological consistency across the different sectors despite pronounced climatic contrasts. This continuity—at odds with reductionist, strictly environmental determinism—speaks to the high adaptive capacity of these architectures in diverse settings [

5]. In this adaptive process, intermediate (mediating) spaces are pivotal: portals, entrance halls (

zaguanes), patios, upper platforms, and plinths manage the interior–exterior gradient, moderating thermal conditions, regulating solar exposure, and aiding drainage in rainy contexts.

Although the overall typology remains stable, we observed significant variation in the frequency, intensity, and assigned functions of mediating spaces according to climate. The portal—the primary interface between inside and outside—exhibits the greatest functional versatility. In cold-climate areas (Sector A, including the canton of Saraguro), portals operate as family production areas (e.g., wool shearing; threshing and drying grains) and as ritual settings—most notably during the Supalata ceremony on the eve of Palm Sunday. In this practice, a procession led by an elder, traverses the community and pauses at each dwelling’s portal to receive food offerings (corn tamales, corn purée), underscoring the socio-spatial centrality of the space. In Sector A—where Indigenous ritual calendars are especially active—these uses intensify, producing patterns of appropriation not observed elsewhere in the province. This is also confirmed by interviews. As Doña Rosa from Saraguro explained: “We use the spaces according to our people’s customs, which we do not want to lose […] In the portals we peel wheat and grind maize, but we also carry out rituals there, such as taking medicine” (Interview R-SAR-03, 2023). These specific ritual uses were not reported in the other two sectors of the study area. Portals also host baptisms and weddings, combining circulation, visibility, and domestic extension.

The portal thus gathers key qualities of public exposure and visibility while remaining a private threshold capable of accommodating many people. In these environments, portals are typically oriented westward to capture late-afternoon sun and are used most in the evening hours.

In temperate zones, portals are associated with collective production activities—for example, coffee drying and loom work—but a higher frequency of serial portals is observed. In these settings, portals also host shared domestic tasks: family members relax after agricultural work and converse; children do homework; laundry is hung to dry; and people shelter from the rain (

Figure 4).

In rural centers, one commonly encounters continuous rows of portals, allowing for covered pedestrian circulation along entire façades; this arrangement correlates with increased rainfall in these sectors.

By contrast, in hot-arid regions, daily life shifts almost entirely onto the portal. Artisanal work—especially the weaving of straw hats—coexists with social uses of gathering and rest. Where no interior living room exists, the portal becomes the principal space for intra-family and neighborly interaction. The ubiquitous hammocks and armchairs attest to prolonged occupancy. Here, portals tend to be wider, projecting outward to form covered exterior areas that also protect the walls.

The zaguán (entrance hall) adapts morphologically with climate while retaining its role as a street-to-patio connector. In hot regions, widths reach ~1.50 m, promoting cross-ventilation; in colder settings, the corridor narrows to ~0.80 m and is often gated to reduce thermal and visual permeability.

Figure 5 illustrates a comparative set of diagrams for three case studies—one per sector (A–C)—showing the architectural plan, orientation relative to the solar path and prevailing winds, mapped activities within the portal, and construction technique. The comparison indicates that climatic gradients condition both technique and siting: in Sectors A and B, portals most often run east–west and are set perpendicular to dominant winds, whereas in Sector C, they tend to face north to capture cooling breezes. In Sector B, the ground-floor portal is commonly left open to cover the sidewalk, enabling sheltered public circulation during rainfall. Productive uses within the portal are broadly similar across cases; ritual practices, by contrast, appear more frequently in settlements with a higher proportion of Indigenous residents.

From a socio-spatial perspective, the arrangement of domestic environments reflects cultural principles that mediate public–private relations and household roles (

Table 1). In Andean rural housing, mediating spaces are not only environmental or structural devices; they also have symbolic and organizational weight. As privileged stages for collective life, their design modulates interaction by regulating visibility, accessibility, and degrees of permeability across domestic domains [

62,

63].

Interviews confirm that portals and

zaguanes act as nuclei of socialization, hosting practices that involve both nuclear and extended kin, and enabling coexistence across generations, genders, and even species. Events are frequently marked by symbolic decorations, including plants and iconographic elements that express Andean cosmology and function as protective, auspicious signs [

26,

53,

59].

Figure 6 documents ritual objects incorporated into the Andean rural house. Crosses placed on the roof ridge are a tangible manifestation of syncretism between local cosmology and Catholicism. Across Andean communities in Ecuador and Peru, terracotta or iron emblems are set on roofs as talismans; the cruciform explicitly references Christian faith. Installation typically occurs during the Wasipichay house-inauguration rite, officiated by the

tayta sulu (master builder) to consecrate and protect the completed dwelling. The

Wasipichay is observed across the three ecological floors analyzed, regardless of owners’ ethnicity, indicating deep cultural embeddedness. Other common apotropaic devices include bull horns and horseshoes hung from the portal and fixed to the main beam, as well as Catholic images—especially the Virgen del Cisne, whose national pilgrimage reinforces the threshold’s protective function.

Vegetal resources also carry defensive meaning: angel’s trumpet (Brugmansia arborea) is often planted beside the portal, believed to neutralize “negative energies.” Its downward-facing flowers are interpreted as linking to the underworld and, by extension, as a barrier to harmful influences. Together, these elements form a symbolic protective system that dialogues with the architecture—portals, ridges, beams—and strengthens the dwelling’s spiritual dimension through the integration of ancestral rites and syncretic Catholic references.

Another revealing aspect is the close relationship between ritual objects and the land. These objects are often plants or animal parts imbued with symbolic or magical significance. In the Andean tradition, natural elements such as mountains and rivers are often anthropomorphized and believed to possess masculine or feminine energies, reinforcing the spiritual connection between inhabitants and their environment.

The research also showed how the Andean rural house is conceived as a collectively produced habitat, structured through the minga, a communal work practice that brings together different actors to build, maintain, or transform both private and collective structures.

In Sector A, the building

minga begins with ceremonial acts. Those intending to build invite the Tayta Sulu (master mason) and offer mati uchú and chicha as symbols of reciprocity and commitment. Some communities formalize this relationship through a signed Maki Hapishka (labor contract). The owner and Tayta Sulu then define the building type, after which the master lays out and levels the plot (kucha hapina) and commences construction according to the agreed terms [

64].

Plot marking is the sole responsibility of the

Tayta Sulu, while foundation excavation is carried out collectively by

minga participants, including apprentice masons. Subsequent phases remain collaborative, with no exclusions by gender or age. These shared actions constitute the practical conduit for intergenerational knowledge transmission, embedding learning in collective practice. This participatory system reinforces the centrality of community involvement in shaping the built environment and highlights how spaces are not just inhabited but also socially co-produced [

23,

65].

Moreover, forms of inclusion and coexistence that transcend the human were observed across the three sectors analyzed. As shown in

Figure 7, basements or upper portal platforms commonly shelter small domestic animals—cuyes (guinea pigs), chickens—living in close proximity to the home. This proximity reveals a relational conception of space in which bonds with other species are integral to rural lifeways [

25,

29].

Overall, the evidence supports the view of the rural house as not only an adaptive architectural form but also a system that generates perceptual and emotional well-being. The everyday appropriation of particular spaces—sitting in the portal at sunset, tending a corner garden in the patio, sharing meals, or resting in the

zaguán—strengthens belonging, identity, and cultural continuity. In this sense, architecture does not impose itself as an object; it accompanies and sustains life as a sensitive infrastructure for daily inhabitation [

28].

A further salient result is the architecture’s capacity to embrace change, rooted in the functional flexibility of mediating spaces. Their adaptability is directly tied to environmental, economic, and social sustainability, and therefore to long-term continuity. Although construction systems appear robust and static, semi-open spaces—especially portals, patios, and

zaguanes—are readily reconfigured for new uses and users. Temporary enclosures accommodate shops, cafés, small agricultural areas, or extra rooms as families grow, generating household micro-economies that bolster income (

Figure 8). Crucially, these transformations are typically reversible, allowing a return to the original configuration when needs shift. This reversibility strengthens the resilience of the Andean rural house, consolidating it as a living architectural device in permanent dialogue with evolving household and community needs.

4. Discussion

Social sustainability cannot be defined solely in technical or environmental terms; it also requires consideration of its cultural and symbolic dimensions. In the case of Andean dwellings in Ecuador, the symbolism embedded in the architecture reflects the deep cultural stratification of the territory—resulting from the layering of Indigenous traditions and external influences, particularly colonial Catholicism—which have become intricately interwoven over time. This symbolic dimension is closely tied to the intergenerational transmission of knowledge: many practices persist thanks to inherited know-how, passed down orally or through everyday experience. Thus, rituals are not only preserved but are also continuously recreated and re-signified, shaping a living architecture imbued with memory and cultural intervention [

27].

Within this aforementioned context, the minga—a communal, reciprocal work practice—functions as a primary vehicle for the oral and practical transmission of technical knowledge. Fieldwork identified vernacular resources that underpin the material resilience of buildings and demonstrate a systematic, resource-aware application of local know-how. Adobe dosage varies slightly by locality, though the baseline ratio (≈40% clay, 30% silt, 30% sand) remains within recommended standards. Stabilization commonly incorporates organic fibers to reinforce the matrix: depending on availability, communities add cattle manure, wheat straw, sugar-cane bagasse, or shredded maize stalks, underscoring a circular-economy logic. In the lowlands (Sector C; <800 m a.s.l.), lightweight bahareque infill (bamboo-and-mud panels ≤12 cm) prioritizes rapid thermal dissipation and low material consumption. At higher altitudes, where cold winds prevail, perimeter walls are extended to shield the corridor and create an aerodynamic barrier (see Fig. 9, “Manu” dwelling). Roof design likewise responds to climate: pitched roofs expel rainfall and, in warm zones, enhance attic ventilation. Timber rafters are secured with the Andean mortise-and-wedge joint (≈120 mm embed, oblique wedge), a metal-free connection that is rigid yet reversibly demountable.

Geometrically, case studies in Sectors A and B consistently reproduce an elongated rectangular plan with an approximate 2:1 long-to-short axis ratio. By contrast, in Sector C, this proportionality diminishes: plans remain rectangular but tend toward greater overall depth and reduced contrast between length and width (

Figure 9). This shift likely reflects hot-climate requirements for deeper shaded areas, whereas in cooler sectors, a larger sun-exposed façade is advantageous. The unit of measurement is the

vara castellana; INPC documentation confirms recurrent dimensional modules of 16:8 or 14:7

varas [

64]. These modules vary with plot characteristics and available space, evidencing situated, adaptive knowledge. Across ecological zones, the portal maintains a depth-to-span ratio of ≈1:2;

zaguanes range from ~1.50 m wide in warm areas to ~0.80 m in cold areas, while preserving a width-to-height ratio of ≈1.2 to ensure daylight and airflow.

Taken together, these aforementioned patterns substantiate the notion of vernacular “constructive intelligence” and support the thesis that earthen rural housing operates as living heritage finely attuned to local climate, resources, and socio-cultural requirements in the Andean context.

Within this aforementioned framework, mediating spaces emerge as crucial: they embody both design constraints and traditional construction practices while structuring rural social life. Their persistence in traditional architecture responds to a deeply rooted cultural logic that links domestic and communal realms, forged over generations through shared experience and environmental adaptation. This aligns with Tamayo’s work [

53], which underscores the patio and arcade as fundamental loci of solidarity and belonging, conceiving the house as a tangible expression of rural dwelling and as a mediator of relations between subject, object, and context. In this sense, mediating spaces contribute directly to cultural sustainability—as a complement to social sustainability—involving the maintenance and preservation of cultural heritage, values, and practices [

66]. On the one hand, it includes the participation of a community, understood as a social nucleus (family, neighbors, acquaintances) and its relationship with cultural aspects in broader sustainability policies. On the other hand, cultural appropriation is a key indicator of sustainability in vernacular architecture. It involves the integration of cultural elements into its morphology, which guarantees physical adaptations such as respect for the terrain, orientation, and the use of natural materials in its construction, as well as through their flexibility and adaptability [

67].

Multifunctionality is central: everyday productive activities—corn shelling, crop drying, weaving—are intergenerational, fostering inclusion, dialogue, and knowledge transmission. Echoing Arenghi [

68], design should remain human-centered, promoting inclusion, well-being, and social sustainability without compromising architectural quality or freedom of use. Similarly, analyses by Chávez and Sirror [

4,

27] emphasize civic participation, culture, and accessibility as key axes; in Andean rural architecture, mediating spaces reinforce these axes by enabling visual control, social and religious interaction, and productive activities—resonating with discussions of social and cultural life by Dixon, Bacon, and Caistor-Arendar [

69] as well as with the adaptive capacity highlighted by Oliver [

70] and Moosavi et al. [

5].

Demographic dynamics also shape these mediated spaces. During the survey (2023), parishes with higher temporary out-migration (>15%) showed the largest share of reversible portal enclosures. This pattern reinforces current policy initiatives—e.g., delivery of land-title deeds and parcel-level irrigation (MAG, 2025)—that aim to reduce abandonment and enable adaptive re-use of vernacular housing.

In short, these mediated spaces constitute privileged settings for collective life, where their design modulates social relationships and regulates visibility, accessibility, and the degrees of permeability between different domains of the house [

48,

50].

When situating these aforementioned findings within other Indigenous-majority areas documented in the literature, meaningful parallels emerge—particularly across highland regions—while acknowledging Ecuador’s pronounced cultural and environmental diversity. For this reason, comparisons are restricted to the Sierra; contrasts with coastal or Amazonian contexts would be methodologically unsound. For example, among the Puruhá communities on the slopes of Chimborazo (≈2700–3000 m a.s.l.), populations preserve material construction traditions and inherited lifeways, displaying several typologies. One notable type [

71] comprises single-room, semi-subterranean dwellings with adobe walls and thatched roofs, small doors, and minimal openings to retain heat. When enlargement is needed, a new module is added. At lower altitudes, clay roof tiles become more common; layouts tend to organize two or three interior spaces—much like the typologies studied here—and incorporate a corridor that performs a role analogous to the portal in southern Ecuador (

Figure 10). Likewise, siting logics orient buildings to block prevailing winds and maximize solar gains, mirroring patterns observed in Sector A of the study area.

A brief regional comparison suggests parallel processes elsewhere in the Andes. In high-altitude Peru and Bolivia (≈4000 m a.s.l.), vernacular housing prioritizes thermal insulation, water management, and wind resistance; blocks are often isolated, and semi-covered mediating spaces such as corridors or portals are uncommon, with courtyards serving as the principal articulating element [

72,

73,

74]. At lower elevations and near larger towns (e.g., Cajamarca, Puno), hybridization with colonial forms reintroduces intermediate spaces, mirroring the altitudinal gradient observed in Loja [

74,

75].

In sum, the initial hypothesis is confirmed: mediating spaces are pivotal to social sustainability. By bridging public and private realms, they facilitate community dynamics and foster appropriation of the built environment. Simultaneously, they embed passive climate-adaptation strategies that ensure year-round habitability and continuous use. As platforms for productive, social, and ritual activities, they operate as nodes of encounter that strengthen social capital and participation. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that architectural morphology—as the material expression of social relations—directly shapes social sustainability, creating inclusive, resilient environments that are culturally grounded in a distinct Andean identity.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that intermediate spaces—portals/porches, patios, corridors, and zaguanes—are not ancillary features of Andean rural dwellings in southern Ecuador, but structuring devices of social sustainability. Multifunctional and adaptable, they mediate the interior–exterior gradient, host productive, ritual, and everyday practices, and sustain intergenerational knowledge and belonging.

Methodologically, placing architectural drawings at the center of analysis proved decisive. Redrawn plans and analytical graphics made legible the relationships among parts, the transformations accrued over time, and the ways these spaces anchor the dwelling in its immediate environment. The drawings revealed successive, reversible adaptations—temporary enclosures for commerce or storage, modular extensions for family growth, or seasonal reprogramming of uses—showcasing a capacity for change that preserves core identity.

This study characterizes these spaces as true connectors between domains often considered separate: public and private, productive and domestic, sacred and everyday, the familial and the collective, the house and the territory. Each interaction within them embodies aspects of the Andean worldview: respectful integration with nature, adaptation to topography, the continuity of inherited rituals—even when re-signified through colonial influences. Yet these spaces do not remain anchored in static traditions; they assimilate new patterns of life that are gradually incorporated, enabling the rural dwelling to evolve and respond to emerging needs—thus reinforcing both its cultural and functional resilience.

Climatic and cultural specificities are most evident in the portal (porch). While shared architectural patterns recur across the three macro-zones, the portal’s configuration varies with altitude, climate, and local customs. In dry regions, it acts as a thermal buffer between exterior and interior; in temperate settings, it operates primarily as a social and productive room; and in cold zones, it functions again as a thermal element, typically incorporating lateral walls to shield users from wind and driving rain. These solutions—together with the use of adobe, rammed earth, and bahareque—arise largely from embodied, empirical know-how rather than formal prescriptions, evidencing a vernacular constructive intelligence finely tuned to place.

Recognizing and valuing these intermediate spaces is therefore not merely a historical exercise but a forward-looking design agenda. Reinterpreting portals and zaguanes—their orientations, dimensions, and semi-open character—offers concrete ways to enhance habitability, support household micro-economies, and reinforce cultural continuity. At the same time, the integration of compatible, low-impact technologies can strengthen performance under increasingly variable climates without eroding vernacular logic.

Future work should pair spatial ethnography with instrumented environmental measurements, explore gendered and generational patterns of occupation through longitudinal study, and test co-designed prototypes that update intermediate spaces with contemporary materials and construction systems. In sum, mediating spaces are pivotal to the social and cultural resilience of Andean rural housing: by bridging public and private realms while embedding passive climate strategies, they produce inclusive, adaptable environments that carry living heritage into the future.