Analysis of the Human Barriers to Using Bicycles as a Means of Transportation in Developing Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Data Collection Instrument

- Informed Consent: The first section included the title of the study, the researchers responsible for it, its objective, its procedure, and its estimated duration of 10 to 15 min. It also included a confidentiality statement. Participation was conditional upon explicit acceptance of the informed consent form.

- Sociodemographic Characterization: This section collected data on gender, age, level of education, type of population (urban or rural), socioeconomic stratification, and geographic location (department and city of current residence).

- Barriers and Perception: This was the focus of the instrument, which assessed participants’ perception of various factors. Topics addressed included the following:

- Infrastructure: Quality and availability of bike lanes, safety at intersections, condition of roads, and parking facilities.

- Environmental and Surrounding Conditions: Distance of routes, slopes, weather conditions, odors, exhaust fumes, and poor public lighting.

- Road Safety and Coexistence: The perception of excessive traffic and vehicle speed, as well as a lack of respect from drivers toward cyclists.

- Personal and convenience factors: Access to a bicycle; comfort compared to other modes of transportation; physical fitness; minor mechanical problems; appropriate clothing; and perception of personal safety while riding.

- Psychosocial Factors: Fear of being attacked; perception of cycling as less sociable or enjoyable than other activities; and concerns about personal appearance (e.g., hairstyle).

- Parental Influence (Only for Minors): The final section contained three dichotomous (yes/no) questions that explored parents’ or guardians’ perception of the minor’s ability and safety when riding a bicycle.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis Methodology

2.5.1. Stage I

- I don’t feel safe riding a bike.

- I don’t have access to a bike.

- I’m not fit enough.

- I would get too hot and sweat a lot.

- It’s not convenient because of my other activities.

- Drivers don’t respect cyclists.

- target_bike_use = 0 (not a potential user): A person reported three or more of these barriers as active.

- target_bike_use = 1 (potential user): If a person reported fewer than three active barriers.

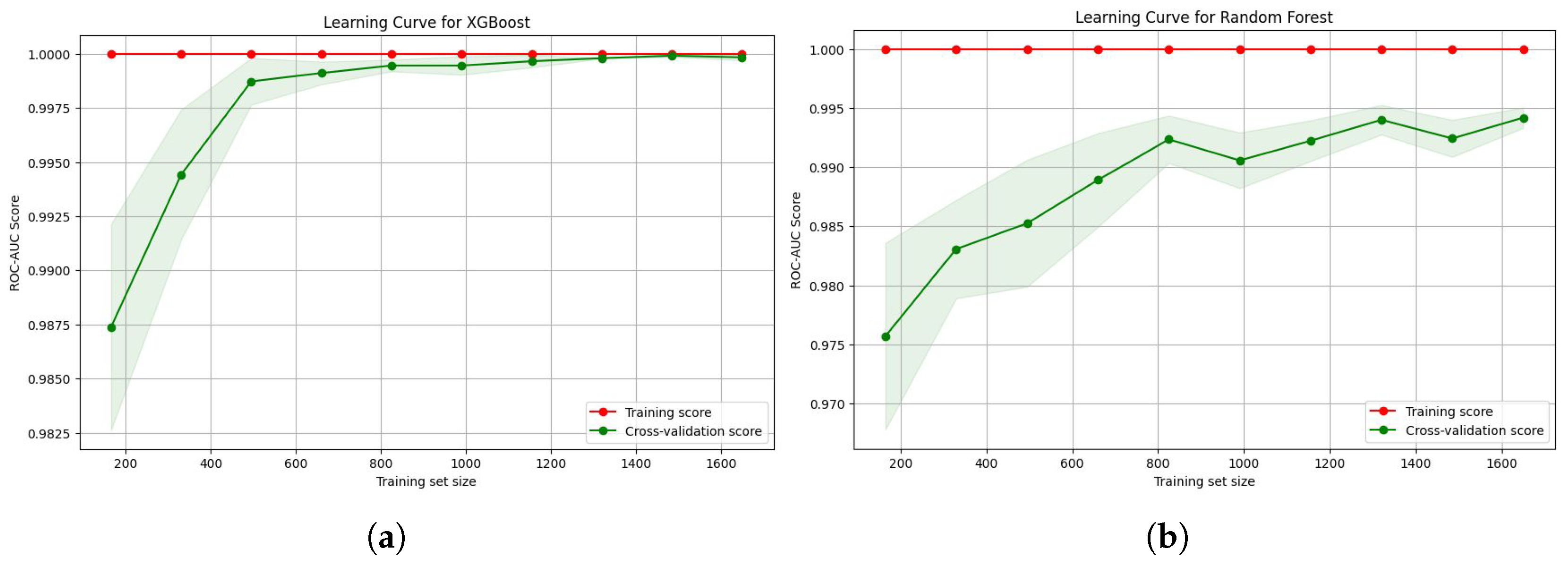

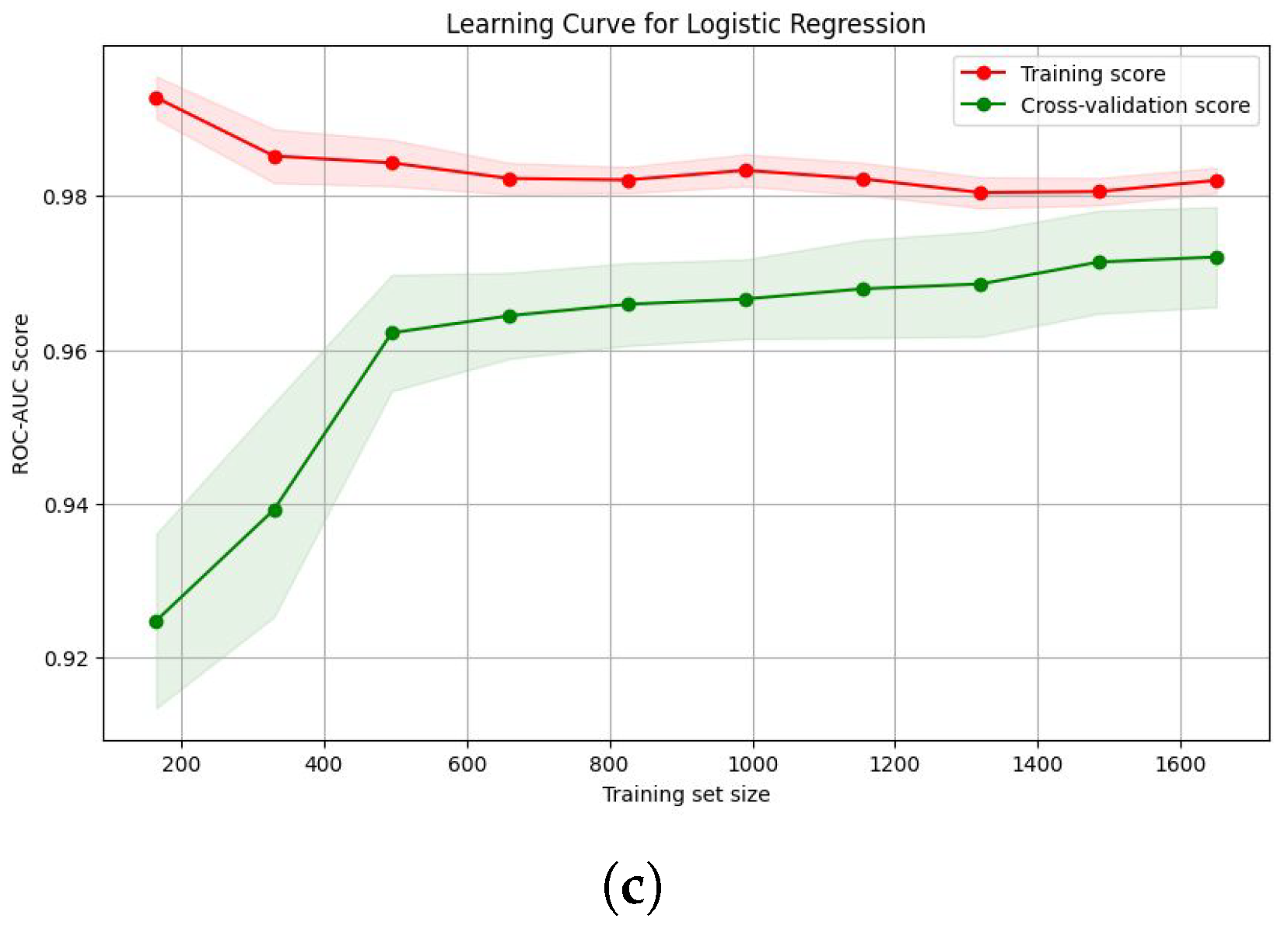

- Logistic Regression: The best performance was achieved with 11-type regularization (which also helps with variable selection), a regularization strength of C = 0.1, and the Saga optimizer.

- Random Forest: The optimal model consists of a forest of 500 trees (n_estimators), where each tree has a maximum depth of 20 levels (max_depth). Specific rules are also applied regarding how and when branches are split to control overfitting (min_samples_split, min_samples_leaf).

- XGBoost: The winning configuration is a slow-learning model (learning_rate: 0.05), composed of 500 very simple trees (n_estimators) (maximum depth of 3). It also uses data subsets (subsample and colsample_bytree), a key technique to ensure the model generalizes well and does not memorize the data.

2.5.2. Stage II

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sociodemographic Information

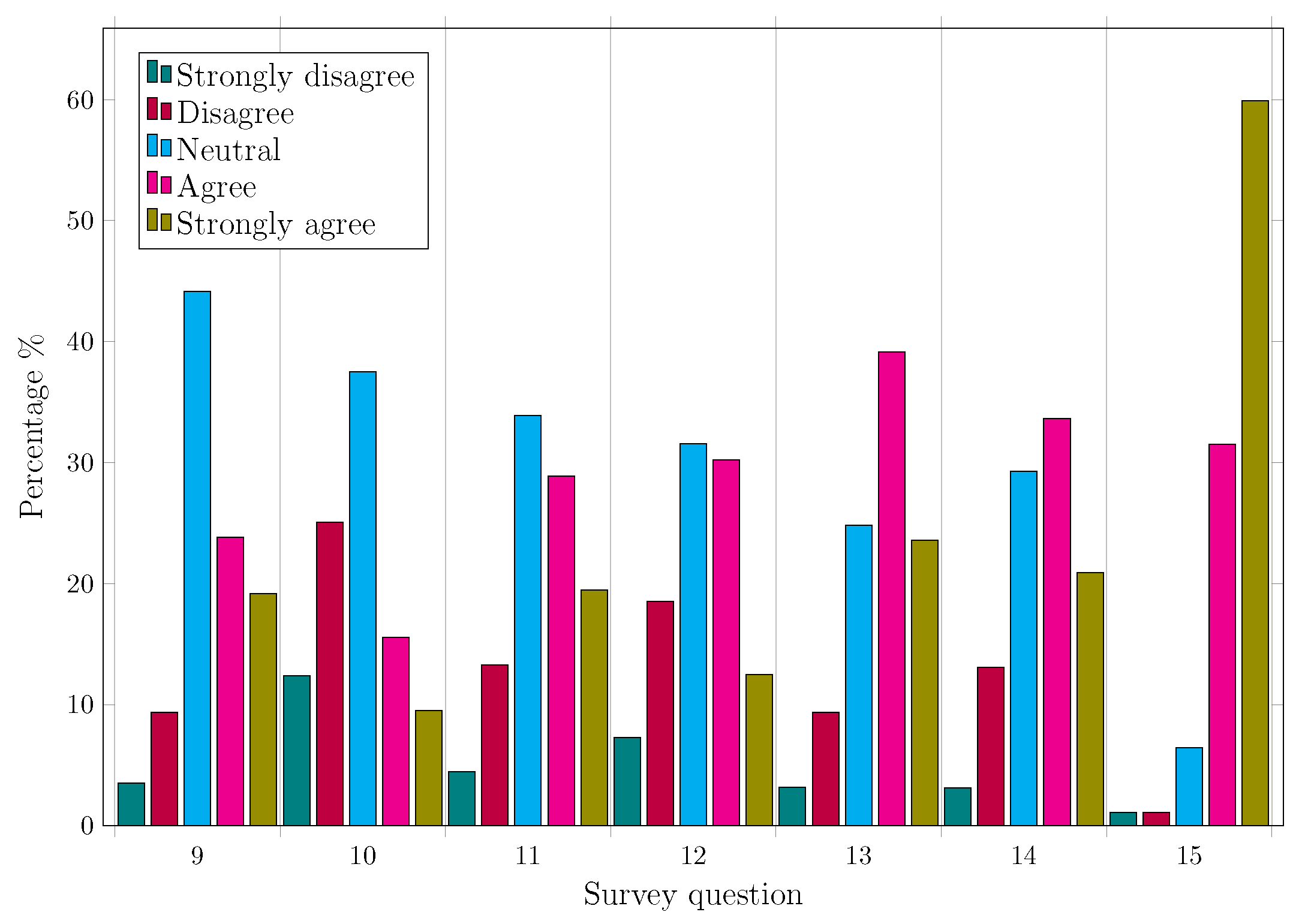

3.2. Environmental Conditions

- 9.

- The places are too far away to cycle to.

- 10.

- My journey is too short to consider cycling.

- 11.

- It would take too long to travel from my place of residence to my final destination.

- 12.

- The slopes are too steep.

- 13.

- The weather conditions are not conducive to cycling.

- 14.

- There are many bad smells and exhaust fumes on the road.

- 15.

- Cycling is good for the environment.

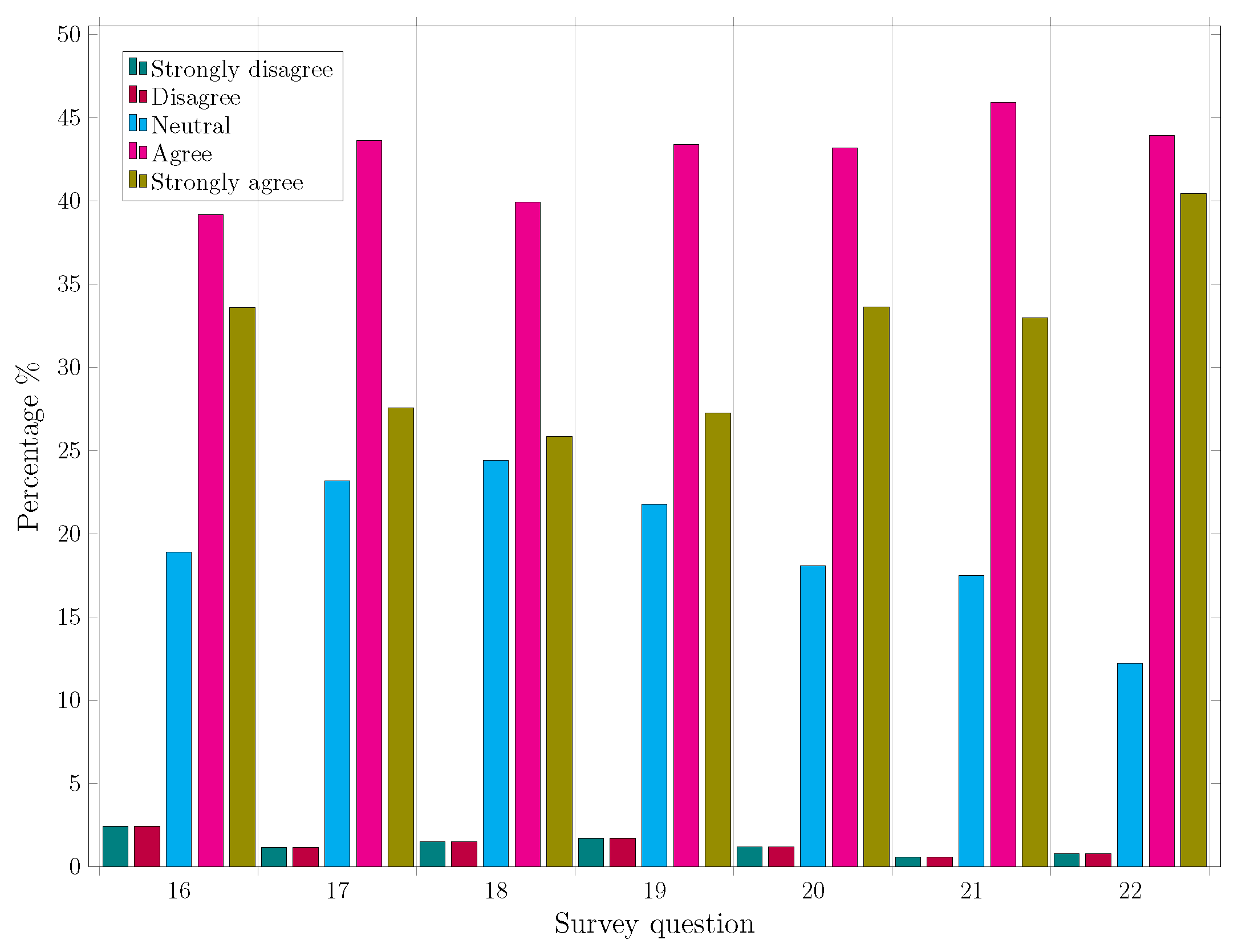

3.3. Infrastructure and Safety

- 16.

- There are no bike lanes, and the ones that exist are of very poor quality.

- 17.

- There are too many intersections, and the intersections are not safe for cyclists.

- 18.

- The roads are too narrow for cycling to be safe.

- 19.

- Street lighting is poor.

- 20.

- Bicycle parking facilities are inadequate.

- 21.

- There is too much traffic, and traffic moves too fast for cycling to be safe.

- 22.

- Drivers do not respect cyclists.

3.4. Personal Perception and Attitudinal Barriers to Bicycle Use

- 23.

- I don’t have access to a bicycle.

- 24.

- I have too many bags to carry/my bags are too heavy.

- 25.

- It requires too much advance planning.

- 26.

- I wouldn’t be able to fix minor mechanical problems (e.g., repairing a flat tire or adjusting the brakes).

- 27.

- Traveling by other means of transportation is more comfortable.

3.5. Practical and Logistical Barriers to Bicycle Use

- 28.

- It is not convenient due to my other activities.

- 29.

- I am not fit enough to ride a bike.

- 30.

- I don’t feel safe riding a bike.

- 31.

- I would get very hot and sweat a lot if I rode a bike.

- 32.

- I am often too tired to ride a bike.

- 33.

- My clothes are not suitable for riding a bike.

- 34.

- Cycling would ruin my hair, especially if I wore a helmet.

- 35.

- I would be afraid of being attacked by harassers or strangers along the way.

- 36.

- It is not appropriate to ride a bike to my usual destinations.

- 37.

- I am too lazy to ride a bike.

- 38.

- Walking is more sociable.

- 39

- Driving or being driven in a car is more fun.

3.6. Evaluating Predictive Models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avila-Palencia, I.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Gouveia, N.; Jáuregui, A.; Mascolli, M.A.; Slovic, A.D.; Rodríguez, D.A. Bicycle use in Latin American cities: Changes over time by socio-economic position. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1055351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Khan, K.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. 2030 Agenda of sustainable transport: Can current progress lead towards carbon neutrality? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 122, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Honda, Y.; Fujii, S.; Kim, S.E. Air Pollution and Public Bike-Sharing System Ridership in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, M.F.; Loureiro, C.F.G.; de Oliveira Neto, F.M. Modeling choice determinants for bicycle-bus integration in developing countries: Case study in Fortaleza, Brazil. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 118, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, E.; Jurdana, I. Bicycle traffic in the cities. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2022, 117, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano Moreno, J.S.; Quintero Gonzáles, J.R. Experiencias de planificación del uso de la bicicleta: Contextos global, latinoamericano y colombiano. Rev. Habitus Semilleros Investig. 2023, 3, 16785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, C.T.; Llerenas, M.T.P. Ciclismo urbano, análisis de indicadores en el contexto latinoamericano  qué se mide? Rev. Electrónica Sobre Cuerpos Académicos Grup. Investig. 2016, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wolniak, R.; Turoń, K. Between Smart Cities Infrastructure and Intention: Mapping the Relationship Between Urban Barriers and Bike-Sharing Usage. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lim, E.S.; Chen, M. Promoting Sustainable Urban Mobility: Factors Influencing E-Bike Adoption in Henan Province, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagufta, T.; Srikanth, S. A comprehensive study of public bicycle sharing system in Ahmedabad through factor, path, and cluster analysis. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, R.P.; de Andrade, M.O.; de Freitas Dourado, A.B. Study of the current law and of the groundings of sustainable urban mobility applied on Joaquim Amazonas Campus, UFPE, Brazil. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 1244–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massin, T.; Kozak, D.; Vecslir, L.; Ortiz, F. Connecting modernist university campuses and their cities. From current mobility patterns to sustainable mobility scenarios for the university of Buenos Aires campus, Argentina. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, D.; Sabogal-Cardona, O. Arguments for cycling as a mechanism for sustainable modal shifts in Bogotá. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 99, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, F.A.; Duran, B.A.A.; Quintero, P.A.A.; Salgado, L.G.; Herrera, R.D.J.G.; Delgado, D.R. Securing mobility in Bucaramanga: Road safety control based on a mobile application. Ing. Solidar. 2024, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANE. Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Vivenda-2018. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-nacional-de-poblacion-y-vivenda-2018 (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Ahmed, S.K. How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Theory When the Sampling-Units are of Unequal Sizes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1942, 37, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogotá Cómo Vamos. Cómo Vamos con La Bicicleta en Bogotá. Available online: https://bogotacomovamos.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Informe-Como-Vamos-con-la-bicicleta.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Gallo, I.; Muños, C. Caracterización de la Economía de la Bicicleta en Bogotá. 2019. Available online: https://observatorio.desarrolloeconomico.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2019-12-31-Caracterizacion-de-la-economia-de-la-Bicicleta-en-Bogota.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesagiri Raamkumar, A.; Tan, S.G.; Wee, H.L. Use of Health Belief Model-Based Deep Learning Classifiers for COVID-19 Social Media Content to Examine Public Perceptions of Physical Distancing: Model Development and Case Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e20493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems; O’Reilly Media: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berrar, D. Cross-Validation. In Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Ranganathan, S., Gribskov, M., Nakai, K., Schönbach, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, F.; Muthukrishnan, N.; Ovens, K.; Reinhold, C.; Forghani, R. Machine Learning Algorithm Validation: From Essentials to Advanced Applications and Implications for Regulatory Certification and Deployment. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2020, 30, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo Hoyos, C.L.; Gómez Sánchez, A.M. Análisis de la elección modal de transporte público y privado en la ciudad de Popayán. Territorios 2015, 33, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseca Clavijo, C. Determinantes de elección modal del transporte en estudiantes universitarios: Un análisis de la literatura actual. Boletín Coyunt. 2017, 13, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamim Kashifi, M.; Jamal, A.; Samim Kashefi, M.; Almoshaogeh, M.; Masiur Rahman, S. Predicting the travel mode choice with interpretable machine learning techniques: A comparative study. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, I.; Lashua, B.; Reid, C. Leisure, Activism, and the Animation of the Urban Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, N.; Monsere, C.M.; Dill, J. Influence of Bike Lane Buffer Types on Perceived Comfort and Safety of Bicyclists and Potential Bicyclists. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2520, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, A.; Bigazzi, A. Perceptions toward pedestrians and micromobility devices in off-street cycling facilities and multi-use paths in metropolitan Vancouver, Canada. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 109, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Moslem, S.; Al-Rashid, M.A.; Tesoriere, G. Optimal urban planning through the best–worst method: Bicycle lanes in Palermo, Sicily. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Transp. 2022, 177, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glachant, C.; Behrendt, F. Negotiating the bicycle path: A study of moped user stereotypes and behaviours in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 107, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Yu, Z.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Agbelie, B. Examining influencing factors of bicycle usage for dock-based public bicycle sharing system: A case study of Xi’an, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutela, B.; Das, S.; Sener, I.N. Exploring the Shared Use Pathway: A Review of the Design and Demand Estimation Approaches. Urban, Plan. Transp. Res. 2023, 11, 2233597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorrano, M.; Danielis, R. Active mobility in an Italian city: Mode choice determinants and attitudes before and during the Covid-19 emergency. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 86, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; McRae, S. Subjectively safe cycling infrastructure: New insights for urban designs. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 101, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannis, G.; Michelaraki, E. Review of City-Wide 30 km/h Speed Limit Benefits in Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, A.; Mayorga, M.; Estrada, M. Modelling individual perception of barriers to bike use. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.; Berkovic, D.; Reeder, S.; Gabbe, B.; Beck, B. Adults’ self-reported barriers and enablers to riding a bike for transport: A systematic review. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 356–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, M.; Tudela, A.; Tapia, A. Analysing the influence of attitude and habit on bicycle commuting. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 82, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, C.; Musmanno, R.; Palmieri, R. Cycle Logistics Projects in Europe: Intertwining Bike-Related Success Factors and Region-Specific Public Policies with Economic Results. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.J.; Hurst, H.T.; Hardwicke, J. Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating in Competitive Cycling: A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingwersen, E.W.; Stam, W.T.; Meijs, B.J.; Roor, J.; Besselink, M.G.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; de Hingh, I.H.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Stommel, M.W.; Daams, F. Machine learning versus logistic regression for the prediction of complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery 2023, 174, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Challenges in the real world use of classification accuracy metrics: From recall and precision to the Matthews correlation coefficient. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.; Beikmohammadi, A.; Arabnia, H.R. Comprehensive Analysis of Random Forest and XGBoost Performance with SMOTE, ADASYN, and GNUS Under Varying Imbalance Levels. Technologies 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Trevizani, R.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Carter, H.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B. The receiver operating characteristic curve accurately assesses imbalanced datasets. Patterns 2024, 5, 100994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, M.; Rodrigue, J.P. The transport geography of logistics and freight distribution. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Gu, X. Mechanical modeling of friction phenomena in social systems based on friction force. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2004, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svašek, M. On the Move: Emotions and Human Mobility. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.J.; Musselwhite, C. Recognised cognitive biases: How far do they explain transport behaviour? J. Transp. Health 2025, 40, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lozano, C.; Hervella, P.; Mato-Abad, V.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; Suárez-Garaboa, S.; López-Dequidt, I.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Sobrino, T.; Campos, F.; Castillo, J.; et al. Random forest-based prediction of stroke outcome. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Liu, Y.; Mei, H.; Shang, H.; Yu, Y. Short-term district power load self-prediction based on improved XGBoost model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Threshold (No. of Active Barriers) | % Non-Potential User (Target = 0) | % Potential User (Target = 1) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥2 | 83% | 17% | Too inclusive: It creates a severe class imbalance and could misclassify individuals with few barriers as “non-potential.” |

| ≥3 (Elected) | 68% | 32% | Methodological balance: Identify a majority group that faces substantial barriers while ensuring that the “potential” group is large enough for robust modeling. |

| ≥4 | 51% | 49% | Too strict: Although it balances the classes, it could be so demanding that it misclassifies individuals with three significant barriers as “potential,” which loses specificity. |

| Model | Parameter | Default Value | Grid Search Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | penalty | l2 | [‘l1’, ‘l2’] |

| C | 1.0 | [0.1, 1, 10, 100] | |

| solver | lbfgs | [‘liblinear’, ‘saga’] | |

| Random Forest | n_estimators | 100 | [100, 200, 500] |

| max_depth | None | [10, 20, 30, None] | |

| min_samples_split | 2 | [2, 5, 10] | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1 | [1, 2, 4] | |

| max_features | ‘sqrt’ | [‘sqrt’, ‘log2’] | |

| XGBoost | learning_rate | 0.3 | [0.05, 0.1, 0.2] |

| n_estimators | 100 | [100, 200, 500] | |

| max_depth | 6 | [3, 5, 7] | |

| subsample | 1.0 | [0.8, 1.0] | |

| colsample_bytree | 1.0 | [0.8, 1.0] |

| Model | Logistic Regression | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.91032 ± 0.01259 | 0.95202 ± 0.00871 | 0.99224 ± 0.00283 |

| Precision | 0.86733 ± 0.02831 | 0.97324 ± 0.01651 | 0.99105 ± 0.01194 |

| Recall | 0.84955 ± 0.01878 | 0.87393 ± 0.02538 | 0.98481 ± 0.01071 |

| F1-Score | 0.85811 ± 0.01918 | 0.92062 ± 0.0149 | 0.98781 ± 0.00441 |

| ROC–AUC * | 0.97206 ± 0.00651 | 0.99388 ± 0.00175 | 0.99983 ± 0.00014 |

| Variable | Coefficient () | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Training_Undergraduate | 0.2995 | 1.3492 |

| The slopes are too steep | 0.2319 | 1.2610 |

| My trip is too short to consider biking | 0.2154 | 1.2403 |

| I am too lazy to ride a bike | 0.2065 | 1.2294 |

| Academic Training_Technologist | 0.2059 | 1.2286 |

| Places are too far to go by bike | 0.2018 | 1.2236 |

| The public lighting is poor | 0.1875 | 1.2062 |

| Population Type_Urban | 0.1791 | 1.1961 |

| There are no bike lanes or they are of very poor quality | 0.1738 | 1.1898 |

| Cycling would ruin my hair, especially if I wore a helmet | 0.1446 | 1.1555 |

| It involves too much advance planning | 0.1349 | 1.1444 |

| Academic Training_Postgraduate | 0.1141 | 1.1208 |

| There is too much traffic on the roads/traffic is too fast for biking to be safe | 0.1115 | 1.1180 |

| Academic Training_Secondary | 0.1105 | 1.1168 |

| There are many bad smells and exhaust fumes on the road | 0.0931 | 1.0975 |

| Gender: Female | 0.0854 | 1.0891 |

| I have to carry too many bags/my bags are too heavy | 0.0695 | 1.0719 |

| Gender: Male | 0.0492 | 1.0504 |

| Academic Training_Technician | 0.0471 | 1.0483 |

| I often feel too tired to ride a bike | 0.0427 | 1.0437 |

| Bicycle parking facilities are not good | 0.0298 | 1.0302 |

| Riding a bike is good for the environment | 0.0038 | 1.0038 |

| Traveling by other means of transport is more comfortable | −0.0593 | 0.9424 |

| Socioeconomic Stratum | −0.0793 | 0.9238 |

| Academic Training_Primary | −0.1023 | 0.9028 |

| The roads are too narrow for biking to be safe | −0.1037 | 0.9015 |

| Driving a car or being driven is more fun | −0.1119 | 0.8942 |

| Biking to my usual places is not appropriate | −0.1486 | 0.8619 |

| Age | −0.1556 | 0.8559 |

| Walking is more sociable | −0.1590 | 0.8530 |

| My clothes are not suitable for biking | −0.1670 | 0.8462 |

| The trip from my residence to the final destination would take too long | −0.2035 | 0.8159 |

| I could not fix minor mechanical problems (e.g., repair a flat tire or adjust the brakes) | −0.2075 | 0.8126 |

| I would be afraid of being attacked by harassers or strangers on my way | −0.2225 | 0.8005 |

| Academic Training_Master’s Degree | −0.2636 | 0.7683 |

| Weather conditions do not favor bicycle mobility | −0.265 | 0.7672 |

| There are too many crossings/The crossings are not very safe for cyclists | −0.3266 | 0.7214 |

| I am not fit enough to ride a bike | −1.2144 | 0.2969 |

| Drivers do not respect cyclists | −1.3012 | 0.2722 |

| I do not have access to a bicycle | −1.3144 | 0.2686 |

| I would get very hot and sweat a lot if I rode a bike | −1.6971 | 0.1832 |

| I do not feel safe riding a bike | −1.8574 | 0.1561 |

| It is not convenient because of my subsequent activities | −1.9566 | 0.1413 |

| Variable | Importance |

|---|---|

| It’s not convenient due to my later activities | 0.1429 |

| I don’t feel safe riding a bicycle | 0.1353 |

| I would get too hot and sweat a lot if I rode a bicycle | 0.0946 |

| I’m not fit enough to ride a bicycle | 0.0734 |

| I often feel too tired to ride a bicycle | 0.0639 |

| I don’t have access to a bicycle | 0.0410 |

| Traveling by other means of transport is more comfortable | 0.0324 |

| My clothes are not suitable for cycling | 0.0316 |

| Drivers do not respect cyclists | 0.0270 |

| Driving a car or being driven is more fun | 0.0263 |

| Cycling would ruin my hair, especially if I wore a helmet | 0.0260 |

| It’s not okay to bike to my regular places | 0.0222 |

| I would be afraid of being attacked by harassers or strangers on my way | 0.0211 |

| Age | 0.0180 |

| I am too lazy to ride a bicycle | 0.0171 |

| I couldn’t fix minor mechanical problems (e.g., fix a flat tire or adjust the brakes) | 0.0170 |

| I have to carry too many bags/my bags are too heavy | 0.0158 |

| Weather conditions are not favorable for cycling | 0.0152 |

| The hills are too steep | 0.0141 |

| It involves too much planning ahead | 0.0135 |

| The roads are too narrow for cycling to be safe | 0.0118 |

| Walking is more sociable | 0.0113 |

| There is too much traffic on the roads/traffic is too fast for cycling to be safe | 0.0100 |

| There are too many intersections/The intersections are not very safe for cyclists | 0.0099 |

| The trip from my place of residence to the final destination would take too long | 0.0093 |

| Bicycle parking facilities are not good | 0.0087 |

| Socioeconomic stratification | 0.0085 |

| The street lighting is poor | 0.0083 |

| There are no bike lanes or they are of very poor quality | 0.0083 |

| The places are too far to go by bike | 0.0079 |

| There are many bad smells and exhaust fumes on the road | 0.0067 |

| Riding a bike is good for the environment | 0.0065 |

| My journey is too short to consider cycling | 0.0063 |

| Department (Currently lives in)_Huila | 0.0040 |

| Department (Currently lives in)_Magdalena | 0.0039 |

| Academic background_Undergraduate | 0.0037 |

| Gender_Male | 0.0035 |

| Department (Currently lives in)_Cundinamarca | 0.0029 |

| Academic background_Technician | 0.0027 |

| Academic background_Technologist | 0.0023 |

| Academic background_High School | 0.0022 |

| Population type_Urban | 0.0020 |

| Academic background_Postgraduate | 0.0016 |

| Academic background_Master’s Degree | 0.0010 |

| Gender_Female | 0.0005 |

| Variable | Importance |

|---|---|

| I don’t feel safe riding a bicycle | 0.2942 |

| It’s not convenient due to my later activities | 0.1760 |

| I would get too hot and sweat a lot if I rode a bicycle | 0.1401 |

| I’m not fit enough to ride a bicycle | 0.0746 |

| I don’t have access to a bicycle | 0.0491 |

| Drivers do not respect cyclists | 0.0428 |

| I often feel too tired to ride a bicycle | 0.0399 |

| Cycling would ruin my hair, especially if I wore a helmet | 0.0202 |

| I couldn’t fix minor mechanical problems (e.g., fix a flat tire or adjust the brakes) | 0.0157 |

| Driving a car or being driven is more fun | 0.0128 |

| I am too lazy to ride a bicycle | 0.0119 |

| My clothes are not suitable for cycling | 0.0114 |

| Weather conditions are not favorable for cycling | 0.0103 |

| The places are too far to go by bike | 0.0095 |

| It involves too much planning ahead | 0.0093 |

| My journey is too short to consider cycling | 0.0092 |

| Bicycle parking facilities are not good | 0.0085 |

| Age | 0.0077 |

| Academic background_Undergraduate | 0.0077 |

| The trip from my place of residence to the final destination would take too long | 0.0076 |

| Riding a bike is good for the environment | 0.0075 |

| The roads are too narrow for cycling to be safe | 0.0060 |

| Walking is more sociable | 0.0051 |

| Traveling by other means of transport is more comfortable | 0.0048 |

| Department (Currently lives in)_Atlántico | 0.0044 |

| There are many bad smells and exhaust fumes on the road | 0.0041 |

| There are no bike lanes or they are of very poor quality | 0.0033 |

| Socioeconomic stratification | 0.0027 |

| Academic background_Postgraduate | 0.0019 |

| The hills are too steep | 0.0018 |

| The street lighting is poor | 0.0000 |

| There are too many intersections/The intersections are not very safe for cyclists | 0.0000 |

| I have to carry too many bags/My bags are too heavy | 0.0000 |

| It’s not okay to bike to my regular places | 0.0000 |

| I would be afraid of being attacked by harassers or strangers on my way | 0.0000 |

| Gender_Male | 0.0000 |

| Academic background_Master’s Degree | 0.0000 |

| Gender_Female | 0.0000 |

| Academic background_Primary School | 0.0000 |

| There is too much traffic on the roads/Traffic is too fast for cycling to be safe | 0.0000 |

| Academic background_High School | 0.0000 |

| Academic background_Technologist | 0.0000 |

| Population type_Urban | 0.0000 |

| Academic background_Technician | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correa Solano, G.A.; Castañeda Muñoz, J.D.; Chappe Chappe, A.; Alvarado Martinez, R.M.; Cardenas-Torres, R.E.; Ortiz, C.P.; Delgado, D.R. Analysis of the Human Barriers to Using Bicycles as a Means of Transportation in Developing Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188264

Correa Solano GA, Castañeda Muñoz JD, Chappe Chappe A, Alvarado Martinez RM, Cardenas-Torres RE, Ortiz CP, Delgado DR. Analysis of the Human Barriers to Using Bicycles as a Means of Transportation in Developing Cities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188264

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrea Solano, Gustavo Adolfo, Julián David Castañeda Muñoz, Angelica Chappe Chappe, Rogelio Manuel Alvarado Martinez, Rossember Edén Cardenas-Torres, Claudia Patricia Ortiz, and Daniel Ricardo Delgado. 2025. "Analysis of the Human Barriers to Using Bicycles as a Means of Transportation in Developing Cities" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188264

APA StyleCorrea Solano, G. A., Castañeda Muñoz, J. D., Chappe Chappe, A., Alvarado Martinez, R. M., Cardenas-Torres, R. E., Ortiz, C. P., & Delgado, D. R. (2025). Analysis of the Human Barriers to Using Bicycles as a Means of Transportation in Developing Cities. Sustainability, 17(18), 8264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188264