Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Turkish Contractors in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Case Analysis

- Project reports and policy documents from the European Commission.

- Financial and technical disclosures from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB).

- Official reports from Polish governmental bodies, notably the General Directorate for National Roads and Motorways (GDDKiA) and the Ministry of Infrastructure.

- Corporate communications, project portfolios, and financial statements from Gülermak A.Ş. submitted to Turkey’s Public Disclosure Platform (KAP).

- Information from partner company disclosures (e.g., Budimex S.A.) and specialized industry journals (e.g., Railway Gazette, Railway PRO).

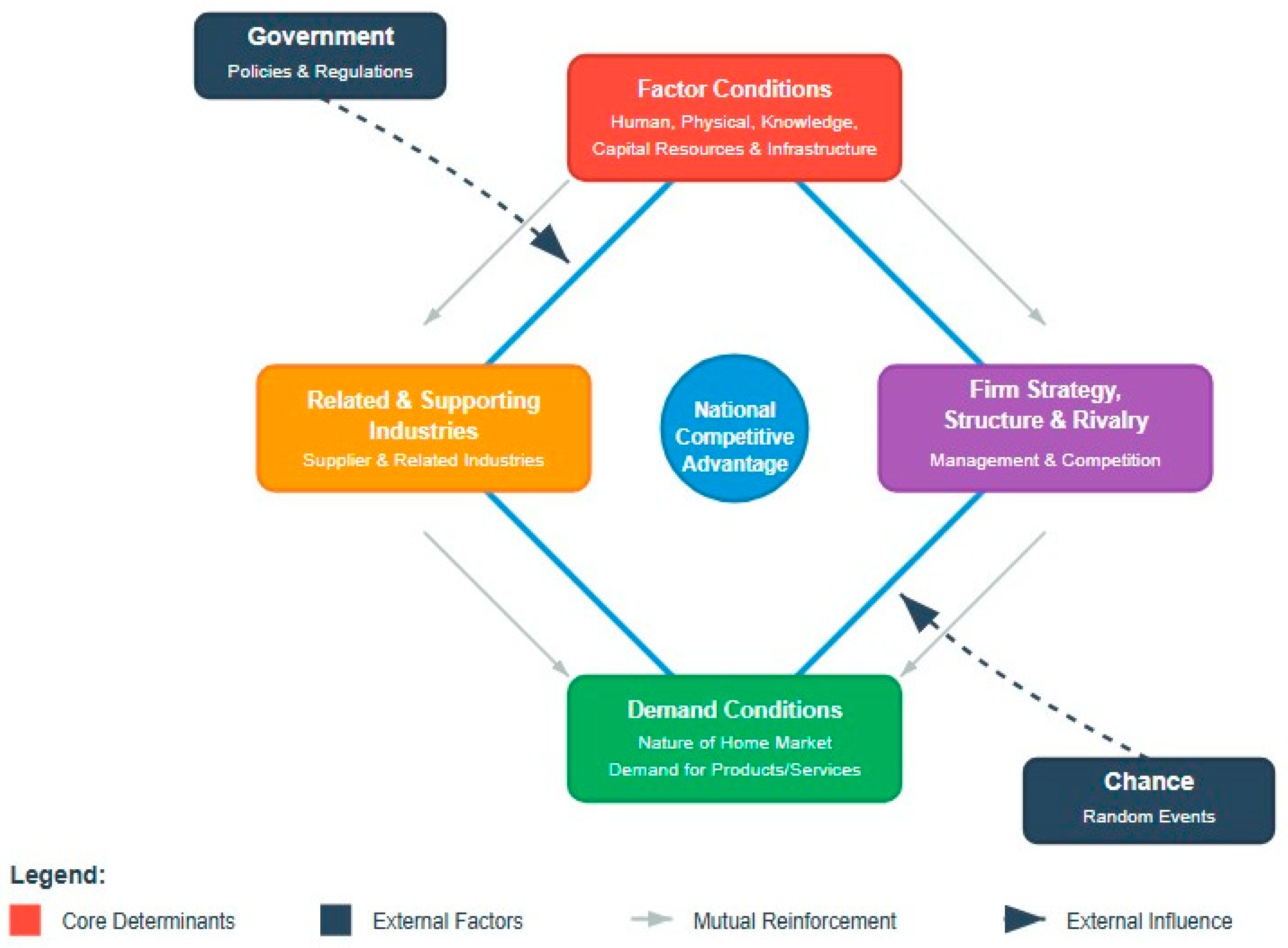

3.2. Analytical Framework

- Factor Conditions: Examining advantages related to labor (skilled and low-cost), resources, and infrastructure.

- Demand Conditions: Assessing how the nature of demand in the Polish market shapes the capabilities of Turkish contractors.

- Related and Supporting Industries: Investigating the role of the Turkish construction materials supply chain and other supporting sectors.

- Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry: Analyzing the entrepreneurial capabilities, management strategies, and competitive behaviors of Turkish firms.

- The Role of Government and Chance: Considering the influence of both Polish and Turkish government policies, as well as fortuitous events, on the competitive landscape.

- Identification of Key Trends and Critical Uncertainties: B Based on these reports, key driving forces shaping the Polish construction market through 2035 were identified, including decarbonisation targets, infrastructure modernization, and digitalisation. Critical uncertainties encompassed geopolitical dynamics, regulatory adaptation, and the technological upgrading of Turkish contractors [43,44,45,48].

- Construction of Plausible Future Scenarios: By combining these uncertainties in a 2 × 2 matrix, four distinct and plausible scenarios were developed—“Carpathian Eagles”, “Reliable Subcontractor”, “Niche Specialist”, and “Fading Footprint”. Each scenario was substantiated by sector-specific forecasts [46,47] and aligned with national infrastructure and energy strategies [43,44,45].

- Derivation of Strategic Recommendations: Strategic implications were drawn from these scenarios to identify “no-regrets” strategies—actions beneficial across all plausible futures. Recommendations were reinforced by documented investment trends, regulatory trajectories, and technological adoption patterns projected to 2035 [43,44,45,48].

4. Findings

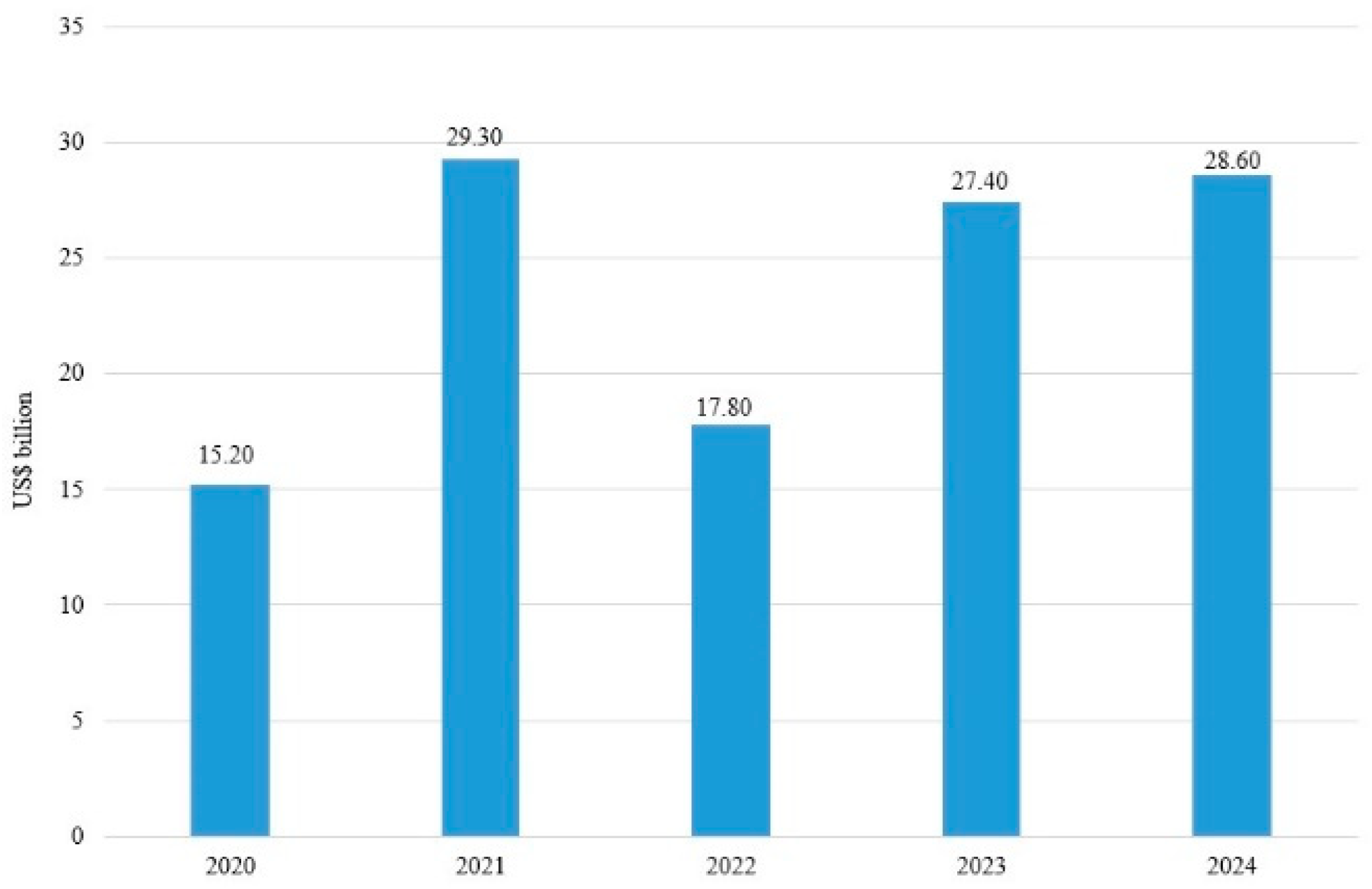

4.1. The Polish National Transportation Infrastructure Landscape

4.2. Gülermak’s Strategic Engagement and Project Portfolio in Poland

5. Analysis and Discussion

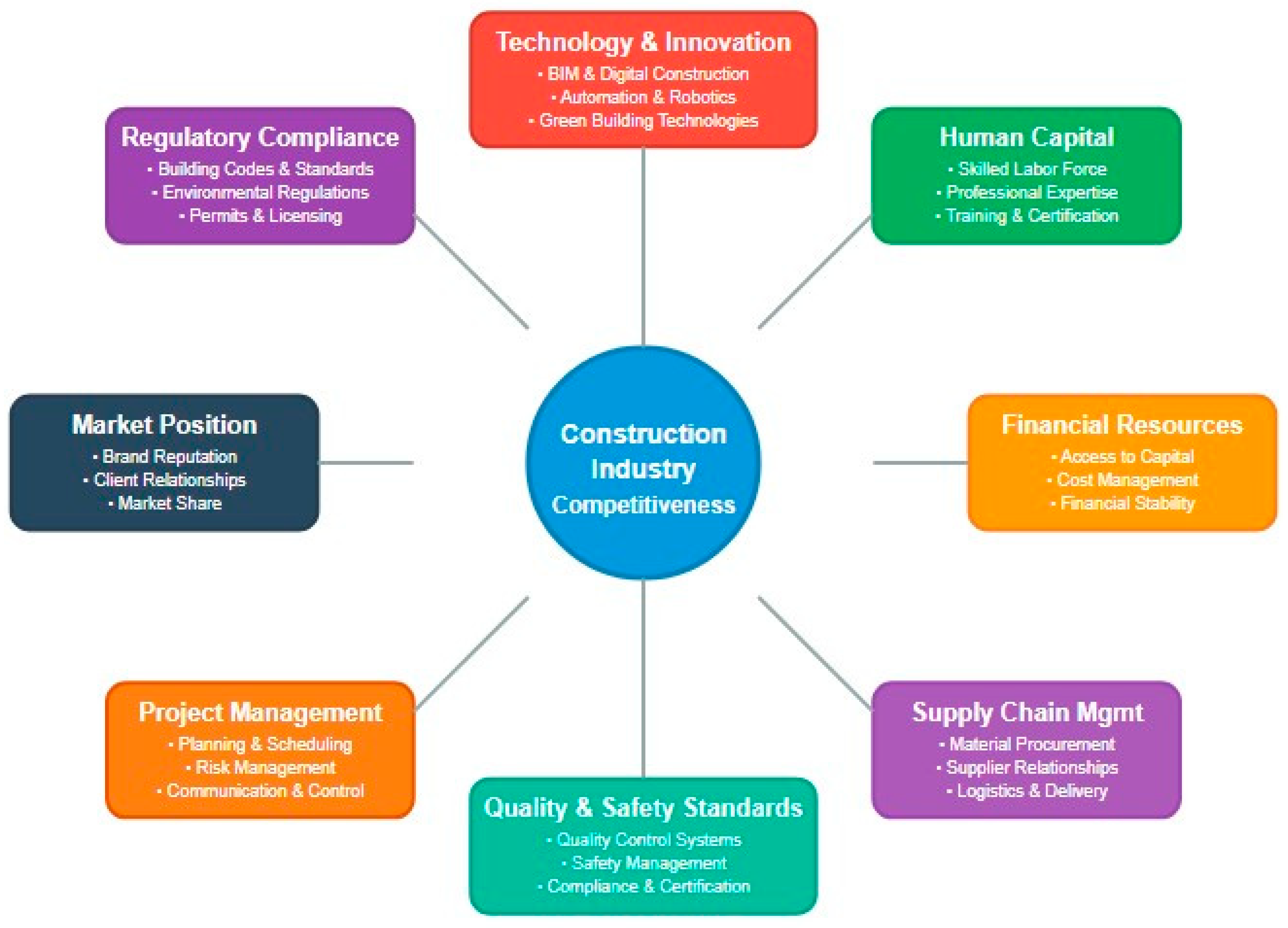

5.1. Analysis of Competitive Advantage: Porter’s Diamond Framework

Competitive Disadvantages and Risks

5.2. Foresight Analysis: Future Scenarios and Strategic Implications

- Key Driving Forces and Inevitable Trends (The “Certainties”)

- Critical Uncertainties (The “Game-Changers”)

- Plausible Future Scenarios (2035)

- Strategic Implications and “No-Regrets” Recommendations

Implementation Pathways for No-Regrets Strategies

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozyurt, B.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Clustering of host countries to facilitate learning between similar international construction markets. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaciak, A.; Halaburda, M.; Bernaciak, A. The construction industry as the subject of implementing corporate social responsibility (The case of Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralun-Bereźnicka, J.; Gostkowska-Drzewicka, M. Trade credit policies in the construction industry: A comparative study of Central-Eastern and Western EU countries. Int. J. Manag. Econ. 2025, 61, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinowsky, P.; Carrillo, P. Knowledge management to learning organization connection. J. Manag. Eng. 2007, 23, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Male, S.; Mitrovic, D. Trends in world markets and the LSE industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 1999, 6, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunhan, S. Factors affecting international contractors’ performance in the 21st century. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2020, 25, 05020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorhon, B.; Demirkesen, S. Analysis of international competitiveness of the Turkish contracting services. Tek. Dergi 2014, 25, 1809–1825. [Google Scholar]

- Budayan, C.; Haghgooie, A.; Birgonul, M.T. Development of a knowledge taxonomy and a tool to support business development decisions in construction companies. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Öz, Ö. Sources of competitive advantage of Turkish construction companies in international markets. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2001, 19, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiner, I.; Tijhuis, W. Work goal orientation of construction professionals in Turkey: Comparison of architects and civil engineers. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska, J. Polish transition towards circular economy: Materials management and implications for the construction sector. Materials 2020, 13, 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbka, J.; Krulický, T.; Šanderová, V. Relationship between variations in valuation methodologies: Evidence from Polish construction market. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2023, 28, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Metelski, D. Unveiling economic synchrony: Analyzing lag dynamics between GDP growth and construction activity in Poland and other EU countries. Buildings 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdzior, A.; Sokol, M.; Styk, A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economic and financial situation of the micro and small enterprises from the construction and development industry in Poland. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głodziński, E. Performance measurement embedded in organizational project management of general contractors operating in Poland. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2021, 25, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; Yurkiewicz, J. Privatization and economic restructuring in Poland: An assessment of transition policies. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 1996, 55, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, J.; Núñez-Cacho, P.; Corpas-Iglesias, F.A.; Molina, V. How to convince players in construction market? Strategies for effective implementation of circular economy in construction sector. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1690760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komurlu, R.; Kalkan Ceceloglu, D.; Arditi, D. Exploring the barriers to managing green building construction projects and proposed solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamasak, R. Firm-specific versus industry structure factors in explaining performance variation: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, G.; Donmez, U. Marketing management functions of construction companies: Evidence from Turkish contractors. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2010, 16, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T.; Ozcenk, I. Marketing orientation in construction firms: Evidence from Turkish contractors. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMB. Available online: https://www.tmb.org.tr/en (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Andrejuk, K. Strategizing integration in the labor market. Turkish immigrants in Poland and the new dimensions of South-to-North Migration. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 2, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol-Smetak, D.; Miciula, I.; Czaplewski, M.; Miluniec, A.; Wysocki, W.; Sikora, M.; Rogowska, K. The impact of IT systems on the safety and competitiveness of construction enterprises. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T.; Budayan, C. Strategic group analysis in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, A.; Ulubeyli, S. Strategic management practices in Turkish construction firms. J. Manag. Eng. 2009, 25, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Birgonul, M.T.; Ozdogan, İ.D. Competitiveness of Turkish Contractors in International Markets. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual ARCOM Conference, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasglow, UK, 6–8 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Strategic perspective of Turkish construction companies. J. Manag. Eng. 2003, 19, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T.; Ozorhon, B.; Eren, K. Critical Success Factors for Partnering in the Turkish Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual ARCOM Conference, Cardiff, UK, 1–3 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak, P.I.; Tas, E. The use of information technology on gaining competitive advantage in Turkish contractor firms. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 18, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S.; Messner, J.I. Competitive positioning and continuity of construction firms in international markets. J. Manag. Eng. 2008, 24, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J.; Isikdag, U.; Goulding, J.; Kuruoglu, M. A Comparative Analysis of the Strategic Role of ICT in the UK and Turkish Construction Industries. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress W78, Cairo, Egypt, 16–19 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hiziroglu, M.; Hiziroglu, A.; Kokcam, A.H. An investigation on competitiveness in services: Turkey versus European Union. J. Econ. Stud. 2013, 40, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, V.; Ulubeyli, S.; Dogan, E. To diversify or not to diversify: A fuzzy decision-making model for construction companies. Gradevinar 2025, 77, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorhon, B.; Kus, C.; Caglayan, S. Assessing competitiveness of international contracting firms from the managerial perspective by using Analytic Network Process. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. Innov. 2020, 3, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Hamid, H.; Pidduck, R.J.; Newman, A.; Ayob, A.H.; Sidek, F. Intercultural resource arbitrageurs: A review and extension of the literature on transnational entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 165, 114007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsmiller, E.; Dikova, D. Internationalization from Central and Eastern Europe: A systematic literature review. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, J.; Kaufmann, C.; Kock, A. The interplay between dynamic capabilities’ dimensions and their relationship to project portfolio agility and success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Martín Martín, O.; Bai, W. Causal foreign market selection and effectual entry decision-making: The mediating role of collaboration to enhance international performance. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herciu, M. Measuring international competitiveness of Romania by using Porter’s diamond and revealed comparative advantage. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 6, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Development and Technology, Poland’s National Building Renovation Plan (NBRP). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Minder, R. Poland’s Big Bet on a New Airport. Available online: https://www.ft.com/poland (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- ORLEN Group. ORLEN Strategy 2035. Available online: https://www.orlen.pl/en/about-the-company/strategy (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence, Poland Construction Market—Size, Share & Industry Analysis (2025–2030 Forecast). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/poland-construction-market (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Market Research Future, Europe Infrastructure Construction Market Size and Industry Report (Forecast 2025–2035). Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/europe-infrastructure-construction-market-48039 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- ING Research, European Contractors Stuck in Neutral as Growth Stalls in 2025. ING Think—Economic and Financial Analysis. Available online: https://think.ing.com/articles/returning-but-low-growth-expected-in-the-european-construction-sector (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Budimex. Available online: https://budimex.pl/en/press/the-consortium-of-gulermak-and-budimex-will-build-the-s19-expressway-with-a-tunnel-and-flyover/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Whitemad. Available online: https://www.whitemad.pl/en/the-general-directorate-for-national-roads-and-motorways-has-resumed-work-on-warsaws-eastern-ring-road/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Railway Pro. Available online: https://fliphtml5.com/ylfj/cffu/Railway_PRO_Magazine_-_December_2022/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Railbaltica. Available online: https://www.railbaltica.org/from-tallinn-to-warsaw-rail-balticas-progress-in-poland-strengthens-high-speed-connectivity-across-europe/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Biznes. Available online: https://biznes.pap.pl/wiadomosci/firmy/plk-otrzymaja-prawie-400-mln-euro-dofinasowania-na-dwa-projekty-w-ramach-rail (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Trade. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/poland-infrastructure-intelligent-transportation-systems (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- CPK. Available online: https://www.cpk.pl/en/news/polands-cpk-mega-project-gains-momentum-major-milestones-and-next-steps (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- EIB. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/projects/pipelines/all/20160050 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Gülermak. Available online: https://www.gulermak.com.tr/tr/Proje/varsova-metrosu-hat-ii-faz-ii (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Railway Pro. Available online: https://www.railwaypro.com/wp/ebrd-provides-funding-for-krakow-ppp-tram-project/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Railway Pro. Available online: https://fliphtml5.com/ylfj/dctc/Railway_PRO_Magazine_-_November_2022/12/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Rokicki, B. Cost underruns in major road transport infrastructure projects—The surprising experience of Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trąpczyński, P.; Halaszovich, T.F.; Piaskowska, D. The role of perceived institutional distance in foreign ownership level decisions of new MNEs. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, N.; Gultekin, D.; Tilkici, D.; Ay, D. An institutional system proposal for advanced occupational safety and labor standards in the Turkish construction industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Kivrak, S. Obstacles of Turkish Construction Workforce in Foreign Countries. In Proceedings of the 1st International CIB Endorsed METU Postgraduate Conference Built Environment & Information Technologies, Ankara, Turkey, 16 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Semiz, F.B.; Aladag, H.; Isık, Z. Barriers to the digital transformation process in the Turkish construction industry. Recent Adv. Sci. Eng. 2023, 3, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emek, U. Turkish experience with public private partnerships in infrastructure: Opportunities and challenges. Util. Policy 2015, 37, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayhan, İ.E.; Jenkins, G.P. Build-Operate-Transfer projects in Turkey: Contingent liabilities and associated risks. Dev. Discuss. Pap. 2016, 1–19. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/68681155/Build_Operate_Transfer_Projects_in_Turkey_Contingent_Liabilities_and_Associated_Risks (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Dogan Erdem, T.; Birgonul, Z.; Bilgin, G.; Akcay, E.C. Exploring the critical risk factors of public–private partnership city hospital projects in Turkey. Buildings 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivrak, S.; Ross, A.; Arslan, G.; Tuncan, M. Construction Professionals’ Perspectives on Cross-Cultural Training for International Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual ARCOM Conference, Leeds, UK, 6–8 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Project Name/Program | Budget (€) | Timeline | Financing Model/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motorway & Expressway Network Expansion | 63 billion | Started: 2004 Target: 2033 | EU Funds State Budget (GDDKiA) Public–Private Partnership (PPP) International Loans |

| Via Carpatia International Route | 7.5 billion | Started: 2015 Target: 2029 | EU Funds State Budget (GDDKiA) European Investment Bank (EIB) |

| 100 New Ring Roads Program | 6.5 billion | Started: 2021 Target: 2030 | State Budget (GDDKiA) EU Funds |

| Warsaw Eastern Ring Road | 1 billion | Started: 2010 Targeted: 2030 | State Budget (GDDKiA) European Investment Bank (EIB) |

| National Railway Programme (KPK) | 17 billion | Started: 2014 Targeted: 2030 | EU Funds PKP PLK, Railway Fund |

| Rail Baltica Corridor (Białystok-Ełk Section) | 1.4 billion | Planned: 2025–2029 | EU’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) PKP PLK, Railway Fund |

| Solidarity Transport Hub (STH/CPK)—Airport | 8.6 billion | Planned: 2026– | State Budget EU Funds Loans |

| Solidarity Transport Hub (STH/CPK)—Rail Network | 30 billion | Planned: 2025– | State Budget EU Funds Loans |

| Project Name | Partners | Budget (€) | Timeline | Financing Model/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warsaw Metro Line II (Central Section) | Astaldi Gülermak PBDiM | 900 million | Started: 2010 Completed: 2015 | EU Funds National Budget |

| Warsaw Metro Line II (Phase II Western Extension) | Astaldi Gülermak | 274 million | Started: 2015 Completed: 2022 | EU Funds European Investment Bank (EIB) |

| Warsaw S2 Expressway (Contract B) | Gülermak PBDiM Mińsk | 176 million | Started: 2015 Completed: 2021 | EU Funds EIB National Budget |

| Świnoujście Tunnel | PORR PORR Bau Gülermak Energopol-Szczecin | 195 million | Started: 2018 Planned: 2022 | EU Funds National Budget |

| Kraków High-Speed Tram (Phase IV) | City of Kraków & PPP Solutions Polska 2 Gülermak | 460 million | Started: 2023 Planned: 2025 | Public–Private Partnership (PPP) EIB EBRD financing |

| S19 Expressway (Jawornik–Lutcza Section) | Gülermak Budimex | 440 million | Started: 2024 Planned: 2031 | Design-Build National Budget |

| Kraków S52 & S7 Expressways | Gülermak Mosty Lodz | 400 million | Started: 2024 Planned: 2026 | EU Funds National Budget |

| Warsaw Metro Line 1 Radio Modernization | Gülermak | 7 million | na | na |

| na: not available | ||||

| Diamond Framework | Related and Supporting Industries | Factor Conditions | Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry | Demand Conditions | The Role of Chance | The Role of Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive advantages of Turkish contractors | Construction materials production | Low cost and skilled labour | Superior entrepreneurial capabilities | Experience in complex projects at home | Cultural and geographic adaptability | The most important customer |

| Construction equipment manufacturing | Skilled and experienced engineers | Intense domestic rivalry | Experience in public projects | |||

| Experienced in challenging environments | Flexibility and responsiveness | |||||

| Needs of Polish construction industry | Supply chain gaps | Specialized expertise | Competitive advantage through efficiency | Sophisticated infrastructure | International collaborations | Infrastructure development |

| Capital access | Strategic alliances | Focus on sustainability & efficiency | Allocating EU funding | |||

| Skilled labor management | Reputation and track record |

| Competitive Strengths | Competitive Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|

| Strong labor management and mobilization capacity | Gaps in design and engineering expertise |

| Extensive experience in large-scale infrastructure projects | Weak formal risk management practices |

| Ability to form joint ventures and partnerships | Financing constraints in PPP projects, limited access to long-term credit |

| Risk appetite and adaptability in foreign markets | Organizational issues: high employee turnover, limited foreign language skills, weak corporate culture |

| Competitive project delivery under tight deadlines | Cost disadvantages in labor deployment abroad |

| Positive reputation in the Polish market (case evidence: Gülermak) | Compliance gaps in OHS and ESG standards |

| EU procurement and institutional barriers |

| Strategy (No-Regrets) | Implementation Pathway (Phased Actions) | Potential Obstacles |

|---|---|---|

| ESG Up-skilling | Obtain BREEAM/LEED certifications within 3–5 years; allocate annual ESG training budgets; establish joint programs with Polish universities | High upfront certification costs; limited ESG expertise; compliance challenges |

| Digital Transformation | Start with BIM pilots; expand to digital twins in large-scale projects; full portfolio adoption within 5 years | Shortage of skilled BIM professionals; software/training costs; organizational resistance |

| Financial Engineering/PPP Readiness | Develop in-house project finance teams; adopt blended finance tools (EU funds + export credits); structured risk-sharing frameworks | Exchange rate volatility; inflation; long approval processes |

| Human Capital & Cross-Cultural Competence | Launch retention programs; provide structured cross-cultural and language training; bilateral vocational training initiatives with Poland | Bureaucratic barriers for labor mobility; higher expatriate labor costs; cultural adaptation issues |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arslan, V. Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Turkish Contractors in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178010

Arslan V. Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Turkish Contractors in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):8010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178010

Chicago/Turabian StyleArslan, Volkan. 2025. "Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Turkish Contractors in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 8010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178010

APA StyleArslan, V. (2025). Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Turkish Contractors in Poland. Sustainability, 17(17), 8010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178010