Abstract

Entrepreneurship development strategies are crucial for translating academic potential into economic and societal value. To achieve this, educational institutions must understand the factors influencing students’ entrepreneurial intentions. While research on academic entrepreneurship exists, comparative studies that explore these factors across different national contexts are scarce. This study addresses this gap through a comparative analysis of student entrepreneurship in Bulgaria, Malta, and Turkey, investigating key factors, such as attitudes toward entrepreneurship (ATE), the role of entrepreneurship education (EEdu), and entrepreneurial inspirations. Based on 415 survey responses collected between April and June 2024, hypothesized relationships were tested using appropriate bivariate statistical analyses. The results indicate that a positive evaluation of running one’s own business significantly increases entrepreneurial intentions, particularly when the business is perceived as safe, realistic, pleasant, and strong. The university’s role is pivotal: students largely relied on institutional support for their business initiatives; showed a strong preference for practical, hands-on educational methods; and identified a lack of entrepreneurship education as a key obstacle. A family background with entrepreneurial parents also positively influenced students’ preference for running their own businesses. Interestingly, the findings challenge a simple dichotomy between employment and entrepreneurship. A preference for full-time employment did not diminish entrepreneurial intentions, suggesting students may view these career paths as complementary or sequential. Conversely, preferences for part-time or self-employment did not have a significant positive impact on entrepreneurial initiatives. These findings underscore the need for universities to provide tailored, practical support and to recognize the complex and non-linear career trajectories envisioned by modern students.

1. Introduction

The concept of academic entrepreneurship is dynamic and complex, making it difficult to classify. Fundamentally, it entails scholars using their research, expertise, and abilities to establish businesses that close the gap between academia and the outside world [1]. The scientific potential generated by universities can be promoted and transferred through commercial applications and be a source of revenue. Educational institutions with a strong entrepreneurial culture are thought to be leaders in molding students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and helping them form close relationships with industry partners. These businesses convert intellectual capital—the information, discoveries, and inventions produced in academic institutions—into useful goods, services, and solutions that advance the economy and society.

Today’s academics are increasingly adopting an entrepreneurial spirit, despite the traditional perception of the academic as a lone scholar engrossed in books and research papers [2]. They are motivated by a desire to see their work applied in the real world, to help solve urgent issues, and to add value outside of academic institutions. For academics, deciding to start their own business is a significant decision that frequently calls for a mental shift and the courage to venture outside of their comfort zones. By connecting academia and industry, academic entrepreneurship can unlock the potential of research for societal needs and economic value, making it a potent force for innovation and advancement [3]. We can anticipate even more contributions from academic entrepreneurs in the years to come if universities continue to encourage entrepreneurship [4].

The drivers of this change are multifaceted. The desire to see their research have tangible benefits is arguably the strongest incentive for many academic entrepreneurs [5]. They are motivated by an overwhelming belief that their research and understanding can help solve societal issues, enhance people’s lives, and change the world for the better. This selfless goal is frequently intricately linked to the core of academic research, which is the search for knowledge to advance humankind. However, the path of academic entrepreneurship is full of both formidable obstacles and exciting opportunities. Academics must manage the frequently incompatible demands of research, teaching, and business, which is a balancing act [6].

Academic institutions are essential for encouraging entrepreneurship and supporting joint business endeavors between students and science disciplines [7]. Universities foster an environment that is favorable to innovation and the real-world application of scientific research by incorporating entrepreneurship education into their curricula and encouraging interdisciplinary projects. Globally, academic institutions have realized how critical it is to incorporate entrepreneurship into their curricula [8] and to maintain constant adaptation to the transformation of the environment [9]. Prominent examples, such as MIT’s Martin Trust Center, programs at Stanford University, and the Innovation & Entrepreneurship Institute at HEC Paris, provide students with funding opportunities, mentorship, and vital business skills to succeed in the entrepreneurial environment [10].

The influence of entrepreneurship education extends beyond academic achievement; it significantly impacts students’ career trajectories and venture success [11]. Studies analyzing the effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions have found that such programs enhance students’ confidence and competence in pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors [12,13]. By providing a supportive environment and practical resources, universities empower students to transform innovative ideas into successful business ventures [14,15]. In summary, the integration of entrepreneurship education within academic institutions, coupled with interdisciplinary collaboration, serves as a catalyst for student-led entrepreneurship initiatives that enrich the educational experience and contribute to economic development [16].

While research has been done on academic entrepreneurship and education, as these subjects gain prominence, it is necessary to identify both the broader issues with the concepts and the challenges that are unique to each nation. This paper addresses this gap by investigating the different aspects that affect students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education. The research object is students from three partner universities: The University of Plovdiv “Paisii Hilendarski” (Bulgaria), The University of Malta (Malta), and Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (Turkey). The novelty of this study lies in its direct comparative approach across three distinct, yet converging, European economies at different stages of entrepreneurial ecosystem development, providing insights that a single-country study cannot offer. The main goal of this study is to identify the attitudes of students towards entrepreneurship and the role of entrepreneurship education in their motivation. To achieve this, the research is guided by the following questions:

- -

- What are students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship as a potential career path?

- -

- How does entrepreneurship education affect students’ motivation to engage in entrepreneurial activities?

- -

- In what ways can universities contribute to the commercialization of scientific potential through entrepreneurship?

- -

- How does the presence of a strong entrepreneurial culture within educational institutions influence students’ perspectives and their ability to form lasting business partnerships?

According to Goldsmith and Kerr [17], students studying entrepreneurship behave more creatively than those studying business. This study was conducted as a part of the “Academic Entrepreneurship Roadmap” project (2023-1-BG01-KA220-HED-000154889), funded by the Erasmus+ Programme. The preliminary results of the research conducted in every university partner were published in a common book [18], but a comparison between the general patterns, gaps, and levels of entrepreneurial motivation has not been made to date. The project demonstrates innovative approaches that enhance educational accessibility and quality, directly supporting sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education). The insights from this research also contribute to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by identifying strategies that bolster skills development and economic resilience.

The paper is structured as follows: following the introduction, the second part presents the literature review, the third part focuses on the research methodology, and the fourth part presents the empirical results, followed by a discussion. The paper closes with conclusions and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Entrepreneurship

The theory of entrepreneurship is interdisciplinary, drawing from psychological, sociological, and economic perspectives. Psychological theories focus on the traits that drive entrepreneurial behavior, such as the need for achievement, with McClelland’s Theory of Needs being a prominent example [19]. Sociological theories emphasize how societal factors, like culture and institutions, influence entrepreneurship, while economic theories include concepts like Joseph Schumpeter’s creative destruction, which highlights innovation as a key driver of economic change [20]. More recent frameworks, such as the Entrepreneurial Value Creation Theory, outline the process from opportunity identification to value appropriation [21]. These theories frame entrepreneurship as a dynamic process, where an individual’s traits and goals (input) are converted into market actions and results (output), all within a specific internal and external context [22,23].

Academic entrepreneurship is grounded in these foundational theories, which provide conceptual frameworks for understanding entrepreneurial motivations and processes. Empirical studies, in turn, offer applied insights into how these theories manifest in practice. This paper critically examines how such empirical findings align with, challenge, or extend these underlying theories, thereby enriching their analytical depth. For instance, foundational theories, like those proposed by Shane [5], outline the key motivations for academic entrepreneurship, while applied case studies, from researchers like Brennan and McGowan [24] and Perkmann et al. [25], offer practical insights into how these theories manifest in real-world settings. While theory establishes the foundational principles, applied findings test and extend them through observation and data collection.

Ultimately, entrepreneurship is a process of discovery, where the entrepreneur adapts to the dynamics of the business environment [26,27,28]. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial behavior identified gaps in current research and highlighted the positive relationship between this behavior and business strategy, which influences decision-making processes [29,30,31,32]. Based on these theoretical considerations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a. (H1a):

Entrepreneurship initiatives are adversely affected by the preference for full-time employment.

Hypothesis 1b. (H1b):

Entrepreneurship initiatives benefit from a preference for self-employment or part-time work.

Hypothesis 2a. (H2a):

Entrepreneurship initiatives are positively impacted by favorable assessments of owning a business.

Hypothesis 2b. (H2b):

Entrepreneurship initiatives are negatively impacted by positive assessments of working for someone else.

2.2. Importance of Academic Entrepreneurship and Education

According to Shane [5] and Audretsch & Keilbach [33], academic entrepreneurship is the application of entrepreneurial skills to academic research, resulting in creative projects that address pressing issues. This strategy not only increases the impact of research but also provides researchers with special career opportunities by boosting funding and recognition [34,35]. However, this approach faces several challenges, including restrictive intellectual property policies; regulatory concerns, such as conflicts of interest; and cultural barriers in the transition from an academic to a commercial environment [36,37].

Student entrepreneurship programs within universities have gained significant attention for fostering entrepreneurial intentions [38]. The entrepreneurial university paradigm emphasizes innovation and a stronger university role in student entrepreneurship [39]. Universities are crucial in providing resources, like incubators, mentorship, and applied courses, that bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world practice. However, a critical challenge remains in ensuring these university-led programs align with student preferences for practical, experiential learning over purely theoretical models. While many institutions incorporate elements like business plan competitions and workshops, a persistent gap is often reported between the pedagogical methods employed and the hands-on, mentorship-driven experiences that students find most valuable for developing tangible entrepreneurial skills.

Fostering successful academic entrepreneurs also requires cultivating soft skills, including opportunity awareness, strategic decision-making, leadership, and interpersonal abilities. Based on the critical role of the university, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3. (H3):

Students depend on the ability of the university to assist them with their entrepreneurial initiatives.

Hypothesis 4. (H4):

Students favor practically oriented teaching strategies in learning entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 5. (H5):

The absence of entrepreneurship education in higher education is cited by students as a barrier to launching a private company.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship Inspiration

Inspiration for entrepreneurship is essential to promoting entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors. This concept refers to the motivating elements that encourage individuals to start their own businesses, which are frequently influenced by educational initiatives, role models, or personal experiences. In the field of entrepreneurship, recent studies have examined the ways in which inspiration can moderate different relationships. Research on entrepreneurial ecosystems has been prominent, with models like Stam and Van de Ven’s integrative model focusing on institutional arrangements, resource endowments, and productive entrepreneurship outputs [40]. Empirical studies examine how the entrepreneurial ecosystem promotes entrepreneurship and value creation at the regional level [34,41,42]. Furthermore, scholars argue that a robust entrepreneurial ecosystem is facilitated by early entrepreneurial success, a strong entrepreneurial culture, supportive public policies, and a cohesive social and economic system [43,44].

Several studies have investigated the moderating effects of entrepreneurship inspiration, examining factors such as an entrepreneurial family background [45,46], personal initiative and motivation [47], and contexts like green entrepreneurship or the pursuit of sustainable development goals. Research suggests that having an entrepreneurial family background serves as a strong moderator between entrepreneurship education and founding passion [48]. Students with entrepreneurs in their immediate family tend to develop higher levels of passion for founding businesses after receiving entrepreneurship education. Personal initiative, for instance, acts as a moderator between intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention, making it more likely that individuals will transform their intentions into actual business ventures [49]. In other contexts, narratives about green entrepreneurship can moderate the relationship between regulatory pressures and legitimacy [50], and university support for sustainable development goals can influence nascent entrepreneurship among students [51].

Recent scholarship has focused on the “third mission” of higher education institutions, which represents the economic and social mission of the university and its contribution to its communities [52,53,54]. As the dynamics of knowledge production and societal expectations evolve, academia may be at a turning point in its strategy to transform from the “entrepreneurial university” to the “university for the entrepreneurial society” [55]. Building upon the extensive literature on entrepreneurial motivation and behavioral theory [56,57], recent studies suggest that entrepreneurship inspiration functions as a critical moderating variable, amplifying the relationship between self-efficacy and innovative actions [58], thereby highlighting its pivotal role in translating motivation into tangible outcomes.

In this sense, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6. (H6):

The university has the potential to inspire young people toward entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 7a. (H7a):

Students whose parents run their own businesses are more likely to prefer running their own business.

Hypothesis 7b. (H7b):

Students whose parents do not run their own businesses are more likely to prefer full-time employment.

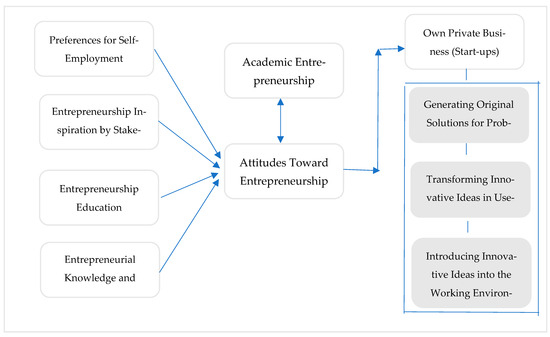

The conceptual framework guiding this research, which illustrates the hypothesized relationships between these key constructs, is presented in Figure 1. Appendix B presents a summary about the hypotheses’ development related to a broad literature review.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model. Source: Аuthors’ elaboration.

3. Methodology

In this study, we employed a quantitative research methodology to investigate university students’ perspectives on academic entrepreneurship. The following sections detail the data collection, sampling, conceptual framework, and analysis procedures.

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling Framework

To collect data, we used a survey questionnaire that included both quantitative scales and several supplementary open-ended questions. We have chosen this approach for its ability to provide both standardized data for statistical analysis and individual perspectives through open-ended responses [59]. While the open-ended questions provided a valuable context for the research team, this paper focuses on the quantitative analysis of the standardized data to test the research hypotheses. The survey instrument was developed based on a comprehensive review of the existing literature on academic entrepreneurship and refined through expert feedback from the professors of the fields of entrepreneurship and education at participating universities. Before widespread distribution, the survey instrument underwent a pilot test with a group of students (n = 118) at the University of Plovdiv Paisii Hilendarski to ensure clarity and validity and to make necessary refinements [60]. Based on the feedback from the pilot study, we made minor revisions to the wording and question order.

The target population consisted of undergraduate and postgraduate students at three public universities participating in the “Academic Entrepreneurship Roadmap” project. These universities were selected due to their representation of diverse educational and cultural contexts within Europe and their active involvement in promoting academic entrepreneurship, enabling a comparative analysis of student perspectives. A purposive sampling strategy was employed, targeting students across various disciplines within these partner universities to capture a broad range of perspectives. We acknowledge that this non-probabilistic sampling method may limit the generalizability of the findings and that the sample may be biased towards students more engaged with the university channels through which the survey was distributed. The data collection occurred between April 2024 and June 2024. The survey was administered online through the integrated online system at the University of Malta. A link was distributed through official university channels, including student portals, departmental mailing lists, and announcements in relevant courses, in collaboration with the university administrators and department chairs. The participants were assured of confidentiality and the research-only purpose of their responses. To prevent duplicate submissions, we used an IP address tracking strategy. After excluding incomplete responses and those with excessive missing data, 415 complete and usable responses were retained for the analysis, representing a response rate of 92%.

3.2. Conceptual Framework and Estimation Strategy

The conceptual framework guiding this research is grounded in the literature review and research hypotheses (Figure 1). The research model examines the relationships between several constructs, including attitudes toward entrepreneurship (ATE), defined as the students’ overall evaluation of entrepreneurship as a career; entrepreneurship education (EEdu), encompassing exposure to and perceived quality of entrepreneurship education; entrepreneurship inspirations (EInsp), representing factors motivating students to consider entrepreneurship; Environmental Influences (EIs), reflecting perceived support for entrepreneurship; Promotion of Own Business Development (POBD), indicating students’ confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities; and Entrepreneurship Behavior Intention (EBI), representing students’ intention to pursue entrepreneurial activities.

These constructs were measured using multi-item scales adapted from the existing literature, primarily employing a 7-point Likert or semantic differential scale format. A full description of the survey instrument, including the specific items for each construct, is available in Appendix A.

To test the hypothesized relationships presented in this paper, a series of bivariate statistical analyses were employed, including Chi-square tests of independence and Independent Samples t-tests, using statistical software. This approach was chosen to directly examine the relationships between specific independent and dependent variables, as outlined in each hypothesis.

3.3. The Overall Reliability of the Attitudes Toward Own Business Scale

To assess the internal consistency of the measurement scales, Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and McDonald’s Omega (ω) were calculated. The Cronbach’s Alpha, (α) = 0.909, indicated excellent internal consistency, indicating that most items consistently measure the same underlying construct (Table 1). The McDonald’s Omega, (ω) = 0.920, of the scale measuring attitudes toward “own business”, demonstrated that the scale is highly reliable for measuring the intended construct.

Table 1.

Reliability analysis.

The item–rest correlation shows that most items have high item–rest correlations (0.6 or above), indicating substantial contributions to the scale (Table 2). For example, the item–rest correlation for “Pleasant–Unpleasant” is (0.807); for “Good–Bad” (0.793), and for “Strong–Weak” (0.803). However, two items have a low correlation with the rest of the scale: “Safe–Risky” (0.349) and “Easy–Difficult” (0.141), indicating that these items may measure risk perception or some other dimensions, rather than the general attitude toward business. An analysis of the impact of removing an item on the improvement of the Cronbach’s Alpha showed only a slight improvement in the reliability (α increases to 0.915).

Table 2.

Item reliability statistics.

The scale that was developed to measure attitudes toward employment demonstrates excellent reliability, with both the Cronbach’s Alpha (α = 0.923) and the McDonald’s Omega (ω = 0.926) indicating strong internal consistency (Table 3). Most of the items (e.g., “Exciting–Boring”, “Pleasant–Unpleasant”, and “Good–Bad”) show high item–rest correlations and contribute positively to the scale’s reliability. However, three items—“Safe–Risky” (0.436), “Realistic–Unrealistic” (0.529), and “Easy–Difficult” (0.545)—have weaker correlations and slightly reduce the reliability when included (Table 4). Removing these items, particularly “Safe–Risky”, would improve the scale’s consistency. If retained, their conceptual alignment with the overall construct should be reviewed.

Table 3.

Reliability analysis.

Table 4.

Item reliability statistics.

4. Statistical Analyses of the Results

According to the results of our analysis (Table 5), Hypothesis H1a is not confirmed. Results show that the participants who indicated that they are “Very interested” in full-time employment also mark “Intentions for their own business” (78.3%), which is an indication that the alternative hypothesis should be accepted (χ2 tests = 11.0, df = 3, p = 0.012).

Table 5.

Preferences for full-time employment.

The results of our study did not confirm that preferences for part-time or self-employment have a positive impact on entrepreneurship initiatives. As Table 6 shows, neither Chi-square test is statistically significant.

Table 6.

Preferences for part-time and self-employment and entrepreneurship initiative.

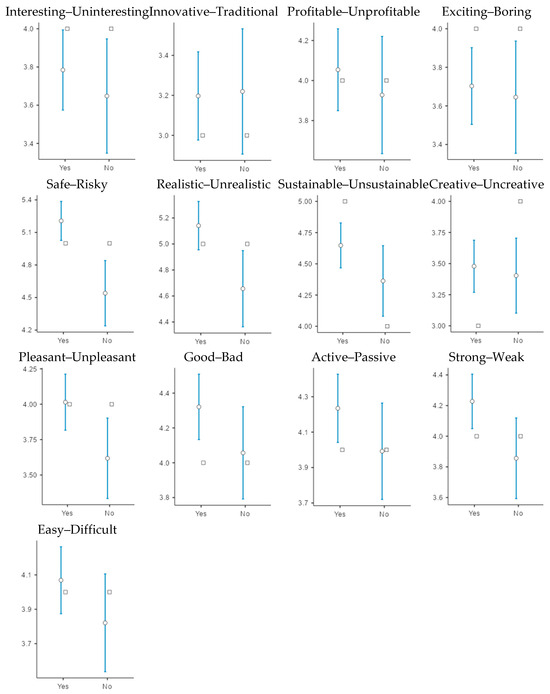

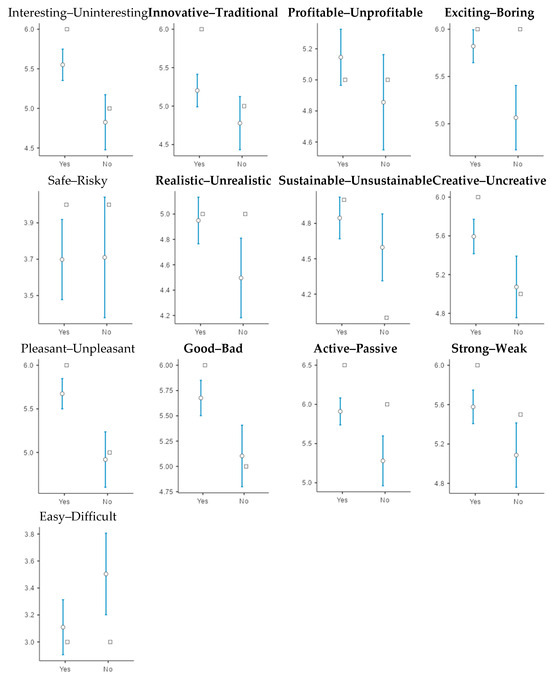

The results of our study (Table 7 and Table 8 and Figure 2) confirm Hypothesis 2a, showing that a positive evaluation of running a business has a positive impact on entrepreneurship initiatives. Our analysis shows that students positively perceive their own businesses as safe (t-test = 3.902 ***), realistic (t-test = 2.796 **), pleasant (t-test = 2.207 *), and strong (t-test = 2.288 *) (Table 9 and Figure 3).

Table 7.

Attitudes toward own business by intentions for own business (Independent Samples t-test).

Table 8.

Attitudes toward own business (Q6R1–Q6R13) by intentions for own business (Q5_new).

Figure 2.

Attitudes toward own business by intentions for own business. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

Table 9.

(a) Independent Samples t-test. (b) Group Descriptives.

Figure 3.

Attitudes toward employment (working for someone else) and intentions for own business. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

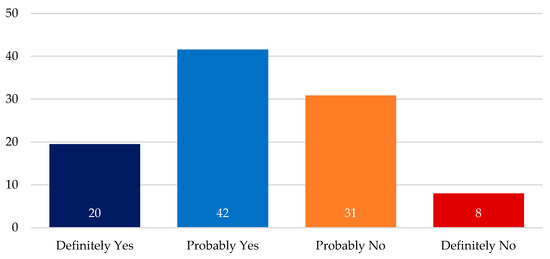

The results obtained indicate that a considerable number of students (62%) rely on the university’s capacity to support them in their business initiatives. As Figure 4 shows, almost two-thirds of the participants in this study expect support from university staff to open their own businesses.

Figure 4.

Expected support from university staff to open own business (%). Source: Based on the data from the survey.

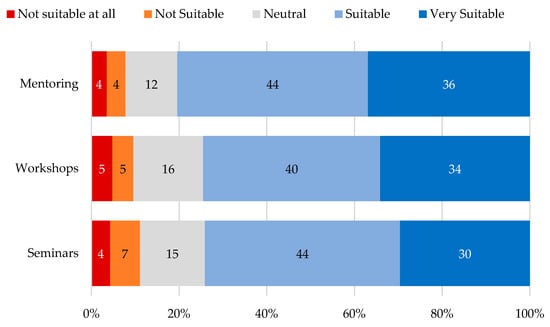

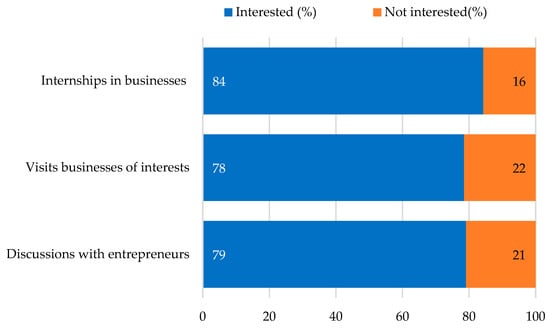

Our analysis and graphical presentation (Figure 5 and Figure 6) demonstrate that a great majority of the students who participated in this study prefer educational methods closer to the practice of learning entrepreneurship.

Figure 5.

Students’ preference of methods for entrepreneurial education. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

Figure 6.

Students’ preference of methods for entrepreneurial education. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

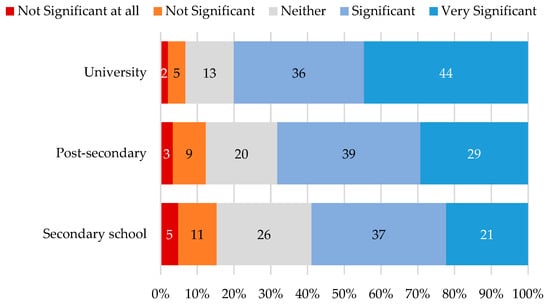

The results of the descriptive analysis (Table 10 and Figure 7) confirm the hypothesis that students consider the lack of entrepreneurship education as an obstacle to someone starting a private business.

Table 10.

Perceived lack of entrepreneurship education during secondary school, post-secondary level, and university.

Figure 7.

The perceived lack of entrepreneurship education during secondary school, post-secondary level, and university. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

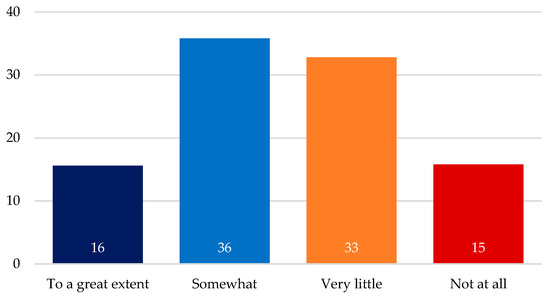

Our results also indicate (Figure 8) that around half of the participants (52%) indicate that universities have the potential to inspire young people toward entrepreneurship.

Figure 8.

The potential of universities to inspire young people toward entrepreneurship. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

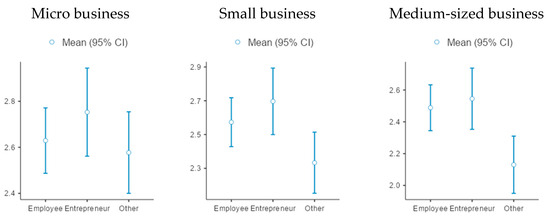

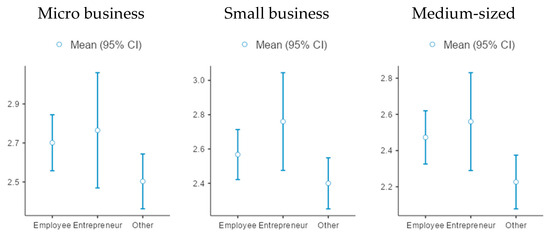

Our analysis confirms Hypothesis 7a, showing that students whose fathers run their own businesses are more likely to prefer running their businesses. The results of the analysis of variance (Table 11) show that students whose parents are entrepreneurs most strongly indicate an interest in running a small (F = 3.889, p = 0.022) or medium-sized business (F = 6.256, p = 0.002). Also, Figure 9 clearly demonstrates that students whose fathers run their own businesses are more likely to prefer running their businesses. Very similar results (Table 11 and Table 12, Figure 9 and Figure 10) were obtained from the analysis of mothers’ employment status and students’ preferences for running their own businesses, further confirming Hypothesis 7a.

Table 11.

Father’s employment status and students’ preferences for running their own business (analysis of variance).

Figure 9.

Father’s employment status and students’ preferences for running their own business.

Table 12.

Mother’s employment status and students’ preferences for running their own business (analysis of variance).

Figure 10.

Mother’s employment status and students’ preferences for running different types of business.

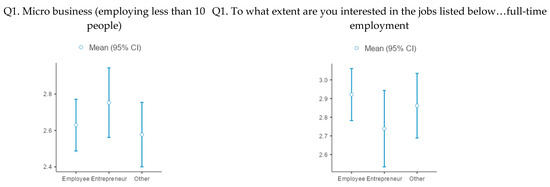

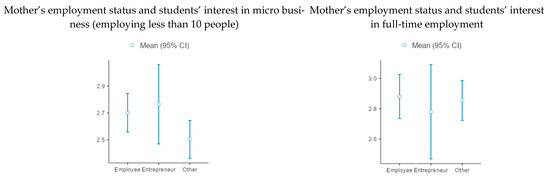

As Table 13, Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16 show that the differences are not statistically significant (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Table 13.

One-Way ANOVA—Father’s employment status.

Table 14.

Group Descriptives.

Table 15.

Mother’s employment status.

Table 16.

Group Descriptives.

Figure 11.

Group Descriptives—Father’s employment status.

Figure 12.

Mother’s employment status. Source: Based on the data from the survey.

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated university students’ perspectives on academic entrepreneurship across three diverse national contexts: Bulgaria, Malta, and Turkey. The findings provide valuable insights into the factors shaping entrepreneurial aspirations among students, revealing both commonalities and context-specific nuances when compared to the existing literature.

One of the most remarkable findings relates to the preference for employment types, which challenges a simple binary view of career paths. Contrary to the initial hypothesis (H1a), students interested in full-time employment also showed significant entrepreneurial intention. This suggests students may not see traditional employment and entrepreneurship as mutually exclusive, but as complementary or sequential career stages. This perspective aligns with the emergence of “hybrid” careers [61,62] and presents a nuanced challenge to traditional applications of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Rather than a direct trade-off, students may view employment as a strategic step to gain capital, skills, and experience before launching a venture, thus shaping their entrepreneurial behavioral control over time.

Furthermore, the hypothesis that a preference for part-time or self-employment would positively impact entrepreneurship initiatives (H1b) was not confirmed. This indicates a multifaceted relationship, where “part-time” intentions might reflect a desire for supplemental income, rather than a primary entrepreneurial drive, particularly in the student population studied. From a theoretical standpoint, while the attitude towards flexible work may be positive, it may not translate into a strong entrepreneurial intention if the perceived desirability (attitude) or feasibility (PBC) for launching a scalable business is not equally high, or if subjective norms in the students’ environments do not strongly support this path.

The robustly positive correlation between a favorable evaluation of owning a business and entrepreneurial intentions (H2a) supports the tenets of the TPB. Specifically, it underscores the pivotal role of a positive attitude (perceived desirability) and perceived behavioral control (PBC) or self-efficacy (perceived feasibility) in the formation of such intentions, a finding consistently echoed in the entrepreneurship literature [37,63,64,65,66]. Conversely, the complex results for H2b suggest that students with entrepreneurial intentions are not necessarily averse to employment, but rather value stimulating work environments, regardless of the chosen path. They perhaps view entrepreneurship as inherently more challenging, requiring greater resilience and specific competencies [67]. This also aligns with the findings where EE did not significantly change attitudes but did impact intention and PBC [68].

The university’s role emerged as crucial, consistent with the literature highlighting higher education institutions (HEIs) as being central to entrepreneurial ecosystems and needing to adapt to foster innovation [61]. Most students (62%) rely on university support (H3), aligning with studies showing that support programs enhance confidence and reduce uncertainty [69,70]. The students overwhelmingly preferred practical, hands-on educational methods (H4), echoing calls for experiential learning, active methodologies [71], mentorship/tutoring [72], and even gamification in entrepreneurship education [65]. A perceived lack of entrepreneurship education was identified as a significant obstacle (H5), emphasizing a clear gap that universities need to address [68,71]. The finding that universities have the potential to inspire entrepreneurship (H6) further supports the idea that the institutional climate [73] and specific initiatives [72] can actively nurture an entrepreneurial mindset [67].

Family background also significantly influences entrepreneurial preference. In line with social learning theory and the role model effect, having entrepreneurial parents increased students’ preference for running their own businesses (H7a) [48,74,75]. However, the hypothesis that students without entrepreneurial parents would default to preferring full-time employment (H7b) was not confirmed. This important finding suggests that while a family background in entrepreneurship is an enabler, its absence is not a deterministic barrier. This implies that other factors, such as those within the university environment (education, support, inspiration) and an individual’s self-efficacy, can play a significant, and perhaps compensatory, role in shaping career intentions. As some studies suggest, entrepreneurship education may be particularly impactful for those without prior exposure [76].

While this study focused on identifying general patterns across the combined student sample, the diverse socio-economic and cultural landscapes of Bulgaria, Malta, and Turkey undoubtedly influence their respective entrepreneurial ecosystems. For instance, the strong reliance on university support (H3) might be more pronounced in economies with more nascent start-up ecosystems compared to those with more mature, external support structures. Similarly, the varying economic viability or cultural acceptance of part-time work could partly explain the non-confirmation of H1b across these specific national contexts. Although a detailed statistical cross-national comparison was beyond the scope of this paper’s primary analysis, future research should delve deeper into these country-specific variations to provide richer, actionable insights for tailoring entrepreneurship education and support at both national and institutional levels.

Integrating these findings, our comparative study underscores the universal importance of positive attitudes, self-efficacy (PBC), university support (especially practical EE), and role models in fostering student entrepreneurship intentions, consistent with TPB and the broader entrepreneurship literature. However, it also reveals context-specific nuances and complexities, such as the non-mutually exclusive view of traditional employment and entrepreneurship (H1a), which challenges some theoretical assumptions and calls for more refined models of entrepreneurial intention. The study highlights the multifaceted nature of how EE impacts different components of intention [70] and underscores the importance of how EE is delivered and who it targets [9,76]. The “stimulated academic heartland” and “integrated entrepreneurial culture” pathways described by Clark [2] require universities not just to focus on commercial outputs [72] but also to embed entrepreneurial thinking and practical skills development deeply within the core student experience.

6. Conclusions

This comparative study across universities in Bulgaria, Malta, and Turkey provides significant insights into the multifaceted nature of academic entrepreneurship intentions among students. The findings confirm the critical role of university support and practical education while also challenging conventional views on the relationship between traditional employment and entrepreneurship. This research offers valuable implications for theory, policy, and educational practice aimed at fostering the next generation of academic entrepreneurs.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of entrepreneurial intention models. Key findings challenge a simplistic binary view of career choice, suggesting students often perceive traditional employment and entrepreneurship as complementary or sequential paths, rather than mutually exclusive options. The results also reinforce the core tenets of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by confirming the strong predictive power of positive attitudes and perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intention, while also highlighting the complex, non-linear influence of factors like employment preferences and family background.

Practically, our study’s findings advocate for a multi-pronged approach by universities and policymakers to better foster academic entrepreneurship. A central recommendation is for universities to move beyond theoretical instruction by integrating practical and experiential entrepreneurship education directly into curricula across diverse disciplines. This educational reform should be complemented by the strengthening of institutional support structures, including incubators, accessible mentorship programs, and clear pathways to funding, which students rely on for their initiatives. Furthermore, universities are encouraged to actively inspire and mentor students by showcasing successful academic entrepreneurs and facilitating direct engagement with the business community through workshops and seminars.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6.2.1. Limitations

Our study has several limitations that open avenues for future research. The reliance on self-reported data from students in three specific universities may limit the generalizability to other institutions or countries. The cross-sectional design captures intentions at one point in time, which does not allow for causal inferences or the tracking of intentions as they evolve into actual entrepreneurial behavior. This may lead to a potential social desirability bias in responses and does not allow for causal inferences. Furthermore, deeper nuances might exist within different fields of study which were not deeply explored in this paper.

6.2.2. Future Research Directions

Future research should aim to address these limitations. Longitudinal studies are needed to track how entrepreneurial intentions evolve and translate into action over time. Detailed cross-national statistical analyses would illuminate how the differing institutional and cultural contexts of Bulgaria, Malta, and Turkey moderate the factors influencing entrepreneurship. Further research could also investigate the impact of diverse role models beyond familial ties and develop educational programs that incorporate real-world examples to enhance their inspirational impact. All the directions are expected to be elaborated in Work Package 3 in the common project the authors participate in.

6.3. Institutional Support

To foster a new generation of innovators, a key recommendation is for universities to significantly enhance institutional support for entrepreneurship. This involves evolving curricula to provide students not only with theoretical knowledge but also with the practical skills and mindset required to drive innovation and economic growth. To develop a more innovative education system, universities should combine hands-on learning, interdisciplinary teamwork, and mindset growth. By offering opportunities to tackle real-world challenges, mentorship, and other resources, universities can better prepare students for success as entrepreneurs and innovators. Promoting a culture of innovation and flexibility in educational programs will encourage students to confidently pursue their entrepreneurial dreams.

To meet the specific needs of students, institutional support should focus on creating immersive learning environments. Programs should be structured to introduce students to near-real business settings where they can apply skills in management, finance, and administration directly to enterprise practices. This approach helps bridge the gap between theory and business reality by allowing students to understand trends and influencing factors in entrepreneurship firsthand.

Furthermore, institutional support must empower students to take practical action and feel inspired on their journey. This includes creating methodologies and programs that allow them to use academic knowledge to address real business needs, thereby supporting their creativity and research initiative. To inspire them, students should be equipped with a variety of examples and case studies of successful academic entrepreneurship that they can follow when facing challenges after graduation.

Finally, this support should facilitate peer-to-peer learning and provide structured guidance. By organizing seminars and workshops where students can meet peers facing similar challenges, institutions can help them exchange experiences and explore their strengths collaboratively. Providing resources such as a formal “Entrepreneurial Journey” based on an “Academic Entrepreneurship Roadmap” can offer a structured pathway with clear examples to guide students in solving problems they will encounter in their future careers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.A.; methodology, M.R. (Martina Riedler) and M.Y.E.; validation, M.R. (Milosh Raykov); formal analysis, M.R. (Milosh Raykov) and M.Y.E.; investigation, all authors; resources, M.N.A. and M.Y.E.; data curation, D.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, M.N.A., M.R. (Martina Riedler), and M.Y.E.; conclusion, M.Y.E., M.R. (Martina Riedler), and M.N.A.; visualization, M.N.A. and D.D.P.; supervision, M.N.A., M.R. (Martina Riedler), and M.Y.E.; project administration, M.N.A.; funding acquisition, M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The paper is part of a project, the Academic Entrepreneurship Roadmap № 2023-1-BG01-KA220-HED-000154889, funded by the Erasmus+ Program, the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Plovdiv Paisii Hilendarski’s ethical commissions. The respondents confirmed their participation using a Consent Form.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire Details

Student Attitudes Toward Entrepreneurship

An international group of researchers is currently conducting a research study that aims to explore student attitudes toward entrepreneurship and educational practices relevant for the development of student attitudes and entrepreneurial skills.

You are invited to complete a short survey that is part of this study. This will take you approximately 15–20 min to complete. Any data collected from this survey will be used solely for the purposes of this study. There are no direct benefits or anticipated risks in taking part. Participation is entirely voluntary, i.e., you are free to accept or refuse to participate.

You will not be asked to provide your name or any other personal data that may lead to your being identified. Furthermore, you may skip over any questions that you do not wish to answer.

If you wish to participate in this study, please click the button that says “I agree to participate.” If not, please close the browser window (or click “I do not wish to participate”).

Should you have any questions or concerns, you may contact the members of the research team via the contact information provided below.

Yours sincerely,

Name: ____________________

Email: ________________

Phone: __________________

DECLARATION BY RESPONDENT: I hereby confirm that I am 18 years of age or older. I am aware that completing and submitting this anonymous questionnaire implies that I am participating voluntarily and with fully informed consent on the conditions listed above.

QUESTION 1

- -

- I agree to participate [Go to the beginning of the survey]

- -

- I do not wish to participate [Go to the end of the survey]

Survey on Student Attitudes Toward Entrepreneurship

QUESTION 2

| To What Extent Are You Interested in the Jobs Listed Below? | ||||

| Not Interested at All 1 | Not Interested 2 | Interested 3 | Very Interested 4 | |

| Full-time employment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Part-time employment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Self-employment (individual work for own account)) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Combined full-time employment and self-employment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Combined part-time employment and self-employment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Micro business (employing less than 10 people) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Small business (employing less than 50 people) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Medium-sized business (employing less than 250 people) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Large business (employing more than 250 people) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Co-operatives | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Other jobs | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 3

| If You Decide to Open Your Own Business, FROM WHOM WOULD YOU EXPECT SUPPORT? | ||||

| Definitely Yes 4 | Probably Yes 3 | Probably No 2 | Definitely No 1 | |

| … University staff (e.g., professors, lectures etc.) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Post-secondary professors and lecturers | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Secondary school teachers | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Parents | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Relatives | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Friends | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Educational institutions | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Technology transfer office at your university | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| … Other organizations | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 4

| What Kind of SUPPORT Is Most Important for People Who Intend to Start Their Own Business, and Who Can Provide This Kind of Support? |

QUESTION 5

| Who Inspires Young People to Start Their Businesses, and to What Extent? | ||||

| Not at All | Very Little | Somewhat | To a Great Extent | |

| Own initiative of young people | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Successful local business owners | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Some widely known business owners | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Secondary school teachers | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| University professors | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Parents | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Relatives | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Friends | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Educational institutions | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Technology transfer office | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Other organizations | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 6

| If You Want to Start Your Business, WHAT KIND OF BUSINESS DO YOU WANT TO START? |

QUESTION 7

| For Each Pair of Adjectives, Please SELECT the Point That Best Describes Your Opinions About OWNING A PRIVATE BUSINESS. | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Interesting | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Uninteresting |

| Innovative | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Traditional |

| Profitable | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unprofitable |

| Exciting | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Boring |

| Safe | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Risky |

| Realistic | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unrealistic |

| Sustainable | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unsustainable |

| Creative | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Uncreative |

| Pleasant | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unpleasant |

| Good | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Bad |

| Active | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Passive |

| Strong | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Weak |

| Easy | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Difficult |

QUESTION 8

| For Each Pair of Adjectives, Please SELECT the Point That Best Describes Your Opinion About WORKING FOR SOMEBODY ELSE. | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Interesting | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Uninteresting |

| Innovative | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Traditional |

| Profitable | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unprofitable |

| Exciting | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Boring |

| Safe | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Risky |

| Realistic | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unrealistic |

| Sustainable | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unsustainable |

| Creative | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Uncreative |

| Pleasant | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Unpleasant |

| Good | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Bad |

| Active | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Passive |

| Strong | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Weak |

| Easy | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | Difficult |

QUESTION 9

| How Often Do You Think About the Following Activities Related to Your Future Work? | ||||||

| Never (1) | Rarely (2) | Seldom (3) | Sometimes (4) | Often (5) | ||

| 1 | Creating new ideas for complex issues | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 2 | Searching out new work methods, techniques, or instruments | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 3 | Generating original solutions for problems | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 4 | Discussing new ideas with your colleagues | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 5 | Acquiring approval for innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 6 | Making important people enthusiastic about your innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 7 | Transforming innovative ideas into useful applications | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 8 | Introducing innovative ideas into the work environment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 9 | Evaluating the effectiveness of innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 10

| Would You Like to Learn Anything About the Following Activities Related to Your Future Work? | |||||

| Definitely No 1 | Probably No 2 | Probably Yes 3 | Definitely Yes 4 | ||

| 1 | Creating new ideas for complex issues | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 2 | Searching out new work methods, techniques, or instruments | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 3 | Generating original solutions for problems | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 4 | Discussing new ideas with your colleagues | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 5 | Acquiring approval for innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 6 | Making important people enthusiastic about your innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 7 | Transforming innovative ideas into useful applications | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 8 | Introducing innovative ideas into the work environment | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 9 | Evaluating the effectiveness of innovative ideas | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 11

| How Would You Evaluate Your Knowledge and Skills About: | |||||

| Very Poor 1 | Poor 2 | Acceptable 3 | Good 4 | Very Good 5 | |

| Innovative work practices? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Process innovation? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Product innovation? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Creating own start-up? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Legislation for opening and managing own business? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Accounting related to managing own business? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Marketing of new products or services? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Financial aspects of a business? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Environmentally friendly or green business practices? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Socially responsible businesses? | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 12

Are you interested in learning the following topics related to starting and managing a business?

| Basic Aspects of Business Planning | Not at all Interested 1 | Not Interested 2 | Neither 3 | Interested 4 | Very Interested 5 |

| Development of entrepreneurship skills | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Information on business management | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Legislative and legal information | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Marketing and sales information | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Financial and accounting information | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Risk management | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Acquisition of financial support and resources | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Networking and business collaboration | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Human resources management | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Financial aspects of a business | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Environmentally friendly or green business practices | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Socially responsible businesses | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Other issues | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 13

| Please Indicate to What Exent Is Each Form of Learning About Entrepreneurship Suitable for You? | ||||||

| Not Suitable at All 1 | Not Suitable 2 | Neutral 3 | Suitable 4 | Very Suitable 5 | ||

| 1 | In-class lectures (30 h of lectures with a certification exam) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 1 | Online lectures (30 h of lectures with a certification exam) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 1 | Combined in-class and online lectures (30 h of lectures with a certification exam) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 2 | Seminars (Short presentations by experts followed by discussions) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 3 | Workshops (intensive group discussion and practical activity) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 4 | Individualized guidance and mentoring on how to develop and manage one’s own business | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 5 | Self-directed learning (Individual reading about entrepreneurship) | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| 6 | Other forms of learning | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 14

Which of the options below do you consider more suitable for your entrepreneurship training? (You can choose more than one answer)

YES/NO

Printed learning materials

Digital learning materials

Access to mass media channels

Specialized courses

Discussions with entrepreneurs

Visits businesses related to students’ interests

Internships in businesses related to students’ interests

QUESTION 15

| For Each of the Following Factors, How Significant an Obstacle Do You Think It Is for Someone Starting a Private Business? | |||||

| Not Significant at All 1 | Not Significant 2 | Neither 3 | Significant 4 | Very Significant 5 | |

| Lack of entrepreneurship education during secondary school | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of entrepreneurship education at post-secondary level | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of entrepreneurship education during university | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of own financial resources | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of national institutional funding support | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of funding support at the EU level | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Difficulty to access bank loans | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of information about funding opportunities | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| High risk to run one’s own business | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of education about risk management | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Difficulties in developing a business plan | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of knowledge of how to run own business | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Difficulties in finding business partners | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Difficulties in finding adequate employees | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Lack of knowledge about human resources management | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

QUESTION 16

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

We need more information about you to analyse the data from this survey effectively. As we already indicated, your answers to this survey will remain completely anonymous.

Please indicate your gender.

- o

- Male

- o

- Female

- o

- Other

- o

- I prefer not to say

QUESTION 17

Please indicate your age: _______________

QUESTION 18

Please indicate the faculty that you attend:

____________________________

QUESTION 19

Which level of study are you currently enrolled in?

- o

- Undergraduate

- o

- Master

- o

- PhD

- o

- Other

QUESTION 20

What year of study are you currently in? __________

QUESTION 21

Are you a full-time or part-time student?

- o

- Full-time

- o

- Part-time

- o

- Other

QUESTION 22

How academically proficient do you rank yourself in your chosen area of study?

- o

- Usually weak

- o

- Below the average for my class

- o

- The average for my class

- o

- Above the average for my class

- o

- Usually top of my class

QUESTION 23

What is the HIGHEST level of education you would like to attain?

- o

- Bachelor’s degree

- o

- Master’s degree

- o

- Doctoral degree

- o

- Professional bachelor’s degree

- o

- Professional master’s degree

QUESTION 24

What is your current employment status?

- o

- Employed Full-Time

- o

- Employed Part-Time

- o

- Self-employed

- o

- Seeking employment opportunities

- o

- I prefer not to say

QUESTION 25

What is your country of origin? __________________

QUESTION 26

Do you consider yourself to be a member of a visible minority group?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No

QUESTION 27

Do you consider yourself to be a member of a disadvantaged group?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No

QUESTION 28

Do you consider yourself to be a person with a disability?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No

QUESTION 29

How would you rate your family income?

- o

- Significantly below average

- o

- Below average

- o

- Average

- o

- Above average

- o

- Significantly above average

- o

- Do not know

QUESTION 30

Does your family have any income in addition to income from employment?

- o

- Yes

- o

- No

- o

- Family members are not employed

- o

- Prefer not to answer

QUESTION 31

How would you describe the place where your family lives?

- o

- Rural area

- o

- Small city or town

- o

- Large city

QUESTION 32

What is your living arrangement?

- o

- Living with both parents

- o

- Living with one parent

- o

- Living by yourself

- o

- Living with friends

- o

- Living with a partner

- o

- Other arrangement

QUESTION 33

| What Is the Highest Level of Education That Your FATHER Completed? |

|

QUESTION 34

| What Is the Highest Level of Education That Your MOTHER Completed? |

|

QUESTION 35

| What Is the Employment Status of Your FATHER? |

|

QUESTION 36

| What Is the Employment Status of Your MOTHER? |

|

Thank you for your participation in this study!

If you are interested in obtaining materials or information about entrepreneurship, you can visit AcEntRoad website [http://academic-entrepreneurship.eu (accessed on 14 May 2025)], where you can access materials and the Internet links to resources, subscribe to the project AcEntRoad mailing list, or receive the information or vouchers for participation in courses about entrepreneurship.

Appendix B

Summary: Hypotheses development related to a broad literature review.

| Hypothesis | Theoretical Basis/Supporting Research |

| H1a: Entrepreneurship initiatives are adversely affected by the preference for full-time employment. H1b: Entrepreneurship initiatives benefit from a preference for self-employment or part-time work. | These hypotheses are grounded in the general theoretical framework of entrepreneurship, which encompasses psychological, sociological, and economic theories. The research challenges the binary view of employment versus entrepreneurship, suggesting students may see them as complementary or sequential paths, a perspective that aligns with the emergence of “hybrid” careers [62,71]. |

| H2a: Entrepreneurship initiatives are positively impacted by favorable assessments of owning a business. H2b: Entrepreneurship initiatives are negatively impacted by positive assessments of working for someone else. | These hypotheses are supported by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which emphasizes the role of positive attitude and perceived behavioral control in forming intentions. This is a consistent finding in the entrepreneurship literature [1,63,65,66,68]. |

| H3: Students depend on the ability of the university to assist them with their entrepreneurial initiatives. | This hypothesis is based on the critical role of the university as a central part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Studies indicate that university support programs enhance student confidence and reduce uncertainty. The “entrepreneurial university” paradigm highlights the university’s role in fostering student entrepreneurship through resources like incubators, mentorship, and applied courses [1,2,39,69,70,71,72]. |

| H4: Students favor practically oriented teaching strategies in learning entrepreneurship. | The literature points to a persistent gap between pedagogical methods and the hands-on, mentorship-driven experiences that students find most valuable. This echoes calls in existing research for experiential learning and active methodologies in entrepreneurship education [1,2,70,71,72]. |

| H5: The absence of entrepreneurship education in higher education is cited by students as a barrier to launching a private company. | This hypothesis relates to the significant impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ career paths. The discussion identifies the perceived lack of this education as a clear gap that universities must address [1,2,69,70,71,72]. |

| H6: The university has the potential to inspire young people toward entrepreneurship. | This hypothesis is linked to the “third mission” of higher education institutions, which includes their economic and social contributions. Recent studies suggest that inspiration is a critical moderating variable that translates motivation into tangible outcomes [52,58,67,73]. |

| H7a: Students whose parents run their own businesses are more likely to prefer running their own business. H7b: Students whose parents do not run their own businesses are more likely to prefer full-time employment. | These hypotheses are supported by the literature on the moderating effects of entrepreneurship inspiration, particularly the influence of an entrepreneurial family background. The findings align with social learning theory and the role model effect. Research suggests that having an entrepreneurial family background can serve as a strong moderator between education and passion for founding a business [48,74,75,76]. |

References

- Etzkowitz, H. MIT and the Rise of Entrepreneurial Science, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B.R. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation, 1st ed.; In Issues in Higher Education; IAU Press; Pergamon Press: Leeds, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; European Commission (Eds.) Entrepreneurship: A Survey of the Literature; Enterprise Papers No 14/2003; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D. The development of an entrepreneurial university. J. Technol. Transf. 2012, 37, 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.A. Academic Entrepreneurship: University Spinoffs and Wealth Creation; Repr. in New Horizons in Entrepreneurship; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, S.; Rhoades, G. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State, and Higher Education; the Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, H.T.; Le, T.T.T.; Tran, A.K.T.; Tran, T.P.T.; Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T. Entrepreneurship education fostering entrepreneurial intentions: The serial mediation effect of resilience and opportunity recognition. J. Educ. Bus. 2025, 100, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sha, Y.; Wang, J.; An, L.; Chen, T.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L. How Entrepreneurship Education at Universities Influences Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediating Effect Based on Entrepreneurial Competence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, D.; Kiryakova-Dineva, T.; Bozkova, R. Needs for Remodeling the Entrepreneurship Education for the Post-COVID-19 Era. In Resilience and Economic Intelligence Through Digitalization and Big Data Analytics; Sciendo: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; pp. 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. The Innovative and Entrepreneurial University: Higher Education, Innovation & Entrepreneurship in Focus; U.S. Department of Commerce, 2013. Available online: https://www.eda.gov/sites/default/files/files/tools/research-reports/The_Innovative_and_Entrepreneurial_University_Report.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Hoog, S.O.; Skoumpopoulou, D. Entrepreneurship Education: Comparative Study of Initiatives of two Partner Universities. AJE 2019, 6, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, T.; Hannon, P.; Penaluna, A. Entrepreneurship education and the role of universities in entrepreneurship: Introduction to the special issue. Ind. High. Educ. 2016, 30, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaicekauskaite, R.; Valackiene, A. The Need for Entrepreneurial Education at University. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 20, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suguna, M.; Sreenivasan, A.; Ravi, L.; Devarajan, M.; Suresh, M.; Almazyad, A.S.; Xiong, G.; Ali, I.; Mohamed, A.W. Entrepreneurial education and its role in fostering sustainable communities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, U.I. The Need for an Effective Collaboration Across Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics (STEM) Fields for a Meaningful Technological Development in Nigeria. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, D.; Minola, T.; Van Gils, A.; Huybrechts, J. Entrepreneurial education and learning at universities: Exploring multilevel contingencies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 945–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Kerr, J.R. Entrepreneurship and adaptation-innovation theory. Technovation 1991, 11, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, M.; Pastarmadzhieva, D.; Gammone, M.; Sidoti, F. Survey on Entrepreneurial Culture and Attitudes Across Students; Plovdiv University Press: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. The Achieving Society; D Van Nostrand Company: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, C.S.; Zachary, R.K. The Theory of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D.; Friederike, W. Conceptualising entrepreneurship in a transition context. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2006, 3, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, B.; Meyer, R. Strategy–Process, Content, Context: An International Perspective, 2nd ed.; International Thomson Business Press: London, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.C.; McGowan, P. Academic entrepreneurship: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2006, 12, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartari, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Brostrom, A.; D’Este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Universities and the third mission: A systematic review of research on external engagement by academic researchers. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, R.B.; Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship. South. Econ. J. 1974, 41, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyurova, V.; Zlateva, D.; Koyundzhiyska-Davidkova, B.; Vladov, R.; Mierlus-Mazilu, I. Digital technologies as an opportunity for business development. Entrepreneurship 2023, 11, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollov, Y.; Dakova, M.; Erturk-Mincheva, A. The just transition in Bulgaria–mission (im)possible. Ecol. Balk. 2024, 16, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Martín, M.-Á.; Castaño-Martínez, M.-S.; Méndez-Picazo, M.-T. Effects of the pandemic crisis on entrepreneurship and sustainable development. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M. New Business Formation and Regional Development: A Survey and Assessment of the Evidence. FNT Entrep. 2013, 9, 249–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Simply Managing: What Managers Do- and Can Do Better; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, C.M.D.S.; Ramos, H.R.; Shinohara, E.E.R.D.; Nassif, V.M.J. Entrepreneurial behavior and strategy: A systematic literature review. REGEPE Entrep. Small Bus. J. 2023, 12, e2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. The Theory of Knowledge Spillover Entrepreneurship*. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T.; Agung, S.D.; Jiang, L. University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Ind. Corp. Change 2007, 16, 691–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. The second academic revolution and the rise of entrepreneurial science. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2001, 20, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.A. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus; Repr. in New Horizons in Entrepreneurship; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schimperna, F.; Nappo, F.; Marsigalia, B. Student Entrepreneurship in Universities: The State-of-the-Art. Adm. Sci. 2021, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; Van De Ven, A. Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Bus Econ. 2021, 56, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. The Correlations Between Academic and Entrepreneur. Impactio. 15 October 2020. Available online: https://www.impactio.com/blog/the-correlations-between-academic-and-entrepreneur (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Jafarov, N.; Szakos, J. Review of entrepreneurial ecosystem models. ASERC J. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2022, 5, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, E.; Mayer, H. The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C.; Moser, S.B. A Longitudinal Investigation of the Impact of Family Background and Gender on Interest in Small Firm Ownership. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1996, 34, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwich, M.; Stuetzer, M.; Sternberg, R. Entrepreneurial role models, fear of failure, and institutional approval of entrepreneurship: A tale of two regions. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 467–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y. The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Cortes, A.F.; Joo, M. Entrepreneurship Education and Founding Passion: The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Family Background. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 743672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogba, F.N.; Ogba, K.T.; Ugwu, L.E.; Emma-Echiegu, N.; Eze, A.; Agu, S.A.; Aneke, B.A. Moderating Role of Initiative on the Relationship Between Intrinsic Motivation, and Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 866869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Zhuang, J. The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Narrative in the Impact of Environmental Regulation on Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurial Legitimacy from a Green Entrepreneurship Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laspita, S.; Sitaridis, I.; Sarri, K. The Effect of Sustainable Development Goals and Subjecting Well-Being on Art Nascent Entrepreneurship: The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.; Langa, P.V.; Pausits, A. One and two equals three? The third mission of higher education institutions. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2015, 5, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piirainen, K.; Andersen, P.; Andersen, A.D. Foresight and the third mission of universities: The case for innovation system foresight. Foresight 2016, 18, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, K.; Dooley, L.; Oreilly, C.; Lupton, G. The entrepreneurial university: Examining the underlying academic tensions. Technovation 2011, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B. From the entrepreneurial university to the university for the entrepreneurial society. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Gregoire, D.A.; Stevens, C.E.; Patel, P.C. Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Wood, E.; Willoughby, T.; Ross, C. Identifying discriminating variables between teachers who fully integrate computers and teachers with limited integration. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Beck, M.S.; Bryman, A.; Liao, T.F. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, M. Academic entrepreneurship and traditional academic duties: Synergy or rivalry? Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 2169–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, B.; Calikoglu, A.; Seggie, F.N.; Seggie, S.H. The entrepreneurial university and academic discourses: The meta-synthesis of Higher Education articles. High. Educ. Q. 2019, 73, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, A.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Aliaga Bravo, V.D.; Teodori de la Puente, R.; Valencia, J.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Briceño Huerta, V.; Vega-Mori, L.; Rodriguez-Correa, P. Factors that determine the entrepreneurial intention of university students: A gender perspective in the context of an emerging economy. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2301812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Mamani, M.A.; Villalba-Condori, K.O.; Flores-Llerena, D.Y.; Cornejo-Paredes, D. SEM Analysis in the Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students. In Proceedings of the IV International Tourism, Hospitality & Gastronomy Congress, Lima, Peru, 25–27 October 2023; CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Volume 3858. Paper 1. [Google Scholar]

- Keshmiri, F. The effect of gamification in entrepreneurship and business education on pharmacy students’ self-efficacy and learning outcomes. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, L. A propensity to thrive: Understanding individual difference, resilience and entrepreneurship in developing competence and professional identity. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 86, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aein, M.; Mahmoudi, H.; Latifi, A.M.; Oori, M.J. Investigating the Effectiveness of Education on the Entrepreneurial Attitude and Intention of Nursing Students: A Semi-Experimental Study. J. Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 17, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.Y.; Yani-de-Soriano, M.; Muffatto, M. The Role of Perceived University Support in the Formation of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Javed, H.; Sun, L.; Abbas, M. Influence of entrepreneurship support programs on nascent entrepreneurial intention among university students in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 955591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araujo Rocha, M.; Botelho Brito, C.V.; Carvalho, M.; Henrique, A.; de Moraes Negrão, L.; de Araújo Moreira, V.; de Oliveira da Cunha Hartuique, H.; de Queiroz Xavier, B.L.; de Moraes Matias, S.; Ellen, E. Teaching Entrepreneurship ın Undergraduate Nursing: Integrative Review. Saúde Coletiva 2025, 15, 13905–13912. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, S. A psychological perspective on entrepreneurship and innovation in universities: The role of educators and tutors in enhancing motivation, interest, and academic success. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassileva, J.; Yalamov, T. Student Entrepreneurship 2023: Insights From Bulgaria; NBU Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024; Available online: https://www.guesssurvey.org/resources/nat_2023/GUESSS_Report_2023_Bulgaria_en.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).