1. Introduction

In an era of rising work intensity, emotional labor, and organizational complexity, the well-being of employees is increasingly recognized as a pillar of sustainable development [

1,

2]. In high-pressure service environments, such as airports, psychological demands are relentless, and the need for emotionally resilient, committed, and high-performing staff is critical not only for operational continuity but also for broader public value [

3,

4,

5]. In this context, psychological resources such as resilience, grit, and happiness at work (HAW) are not merely individual traits; they are strategic capabilities that contribute directly to both the flourishing of individuals and organizational sustainability [

6,

7,

8].

The current shift toward sustainable work systems calls for a deeper understanding of how internal psychological assets can support long-term well-being and performance [

1,

9]. Resilience, or the capacity to recover and adapt to adversity, is increasingly viewed not only as a personal resource but as a sustainability enabler within organizations, reducing burnout, turnover, and stress-related health outcomes [

10,

11,

12].

In contrast to resilience, which reflects adaptive recovery following stress, grit reflects the capacity to sustain long-term effort and purpose in pursuit of meaningful goals. While resilience enables employees to bounce back, grit enables them to press forward [

6,

13,

14].

Happiness at work, encompassing engagement, job satisfaction, and affective organizational commitment, has emerged as a key mechanism through which healthy organizations foster well-being and sustainable productivity [

8,

15,

16,

17]. However, the assumption that all forms of workplace happiness equally support sustainability remains underexamined [

7,

18]. While hedonic forms of happiness may offer short-term satisfaction, eudaimonic well-being, characterized by meaning, purpose, and emotional commitment, may be more consequential for enduring motivation and behavioral persistence [

2,

7].

While resilience, grit, and happiness at work have been individually studied, few studies have examined how these constructs interact in high-pressure settings, specifically how workplace happiness might enhance grit through the mediating role of resilience. This dynamic pathway remains theoretically and empirically underexamined in current organizational research [

6]. This study addresses this gap by exploring how psychological resources, particularly affective commitment and resilience, interact to support grit, a construct essential for long-term goal persistence.

Within airport operations, where unpredictability, emotional labor, and operational precision are constant, the presence of resilience and grit may act as behavioral anchors, enabling employees to remain focused, emotionally stable, and committed to service excellence [

3,

4]. These psychological assets are particularly critical in building long-term human sustainability in workplaces [

1,

6].

This study contributes to the intersection of positive organizational behavior and sustainability by offering a theoretically integrated framework linking resilience and multidimensional workplace happiness to grit [

6,

8,

13]. Drawing on Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build Theory [

19], we examine how emotionally enriching work experiences foster enduring psychological resources that sustain effort over time. Focusing on the aviation sector as a prototypical high-pressure environment, this study investigates how workplace happiness and resilience interact to predict grit, offering new insights for theory, leadership development, and sustainable HR practices. In doing so, this study advances the idea that sustainable organizational practices begin with sustainable people [

1,

9]. We argue that affective commitment and resilience are not only protective factors but also drivers of sustainable behavior, essential for fostering motivation, adaptability, and long-term performance [

12,

16].

Despite growing interest in positive organizational behavior, few models have integrated resilience, grit, and multidimensional happiness at work within a unified framework. Prior studies have tended to examine these constructs in isolation, often treating resilience and grit as stable traits rather than context-sensitive psychological resources [

12,

13]. Moreover, existing research has produced mixed findings; for instance, while some studies suggest that job satisfaction fosters grit through enhanced motivation, others find no significant relationship or even negative effects due to extrinsic motivation crowding out intrinsic drivers [

20,

21]. These inconsistencies highlight the need for more contextualized, integrated models.

The airport context offers a particularly relevant setting to investigate these dynamics. Employees face constant emotional labor, unpredictability, and time pressure, conditions under which psychological resources such as resilience and grit are most likely to be tested. As highly regulated, safety-critical environments, airports require not just short-term coping but sustained, value-aligned effort, making them an ideal context for examining how happiness at work and resilience interact to predict grit and long-term performance.

This has significant implications for leadership, HR design, and corporate social responsibility strategies aimed at promoting health, satisfaction, and behavioral continuity in the workforce [

1,

9].

2. Literature Review

In contemporary organizational behavior literature, HAW is no longer viewed as a transient emotional state but as a multidimensional construct with strategic relevance for individual well-being and sustainable organizational success [

8,

22]. HAW typically comprises engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment, and it has been positively linked to motivation, psychological resilience, and job performance [

7,

15].

HAW is understood not only as a product of individual traits but as an outcome shaped by leadership style, workplace culture, psychological safety, and institutional support [

9,

18]. In high-pressure environments such as airports, HAW serves as both a health indicator and a driver of sustainable human performance [

3,

5]. Resilience, once considered a personal trait, is now recognized as a psychological resource that can be cultivated through supportive environments and inclusive leadership, functioning as a bridge between HAW and sustainable service delivery [

3,

4,

10,

11].

Similarly, grit, defined as passion and perseverance towards long-term goals, is crucial in demanding, safety-critical industries. It enhances employees’ persistence, innovation, and emotional endurance [

6,

13]. Initially viewed as a fixed personality trait, grit is now seen as malleable and context-dependent, influenced by purposeful work and leadership quality [

14,

23,

24].

This study is grounded in Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build Theory of positive emotions, which posits that emotionally enriching experiences at work broaden individuals’ awareness and behavioral flexibility [

19,

25,

26] and, in doing so, build lasting psychological resources such as resilience, motivation, and goal commitment over time. Within this framework, engagement and affective commitment are conceptualized as broadening forces, while resilience and grit are considered as built resources that support sustainable motivation and behavioral persistence.

We conceptualize HAW as a higher-order construct, composed of engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment, affecting grit both directly and indirectly through resilience. For example, affective commitment may promote goals’ pursuit via identity-based motivation, while job satisfaction may enhance grit, particularly when intrinsically motivated [

20].

Our model places resilience as the central mediating mechanism translating workplace well-being into sustained, goal-directed effort. Nonetheless, in tightly coupled systems like international airports, direct effects of HAW on grit are also expected due to the need for rapid decision-making and emotional regulation.

By empirically examining these relationships in a high-pressure organizational context, this study contributes to positive organizational psychology and the development of a sustainable workforce by addressing the interplay between health, resilience, and perseverance under complex work demands.

3. Research Hypotheses

This study is grounded in Fredrickson’s [

19] Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions, which suggests that positive work-related psychological states expand individuals’ cognitive and behavioral repertoires, enabling the development of enduring psychological resources such as resilience, engagement, and perseverance. Within high-stress, mission-critical sectors like aviation, these psychological capacities are not merely personal traits but key components of organizational sustainability and long-term workforce performance.

Applying this framework to the airport context, we propose that resilience, the capacity to recover from adversity, plays a foundational role in enabling positive workplace experiences that contribute to sustained behavioral commitment. This behavioral persistence is conceptualized as grit, defined as passion and perseverance for long-term goals [

13]. In this study, we reconceptualize HAW as a multidimensional construct comprising work engagement, job satisfaction, and affective organizational commitment, each reflecting distinct aspects of a positive employee experience [

17].

From a sustainability perspective, both psychological resilience and grit are essential for reducing employee burnout, supporting service continuity, and maintaining performance in volatile or emotionally demanding environments [

6,

12]. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypotheses:

3.1. Resilience and HAW

Resilient employees are more likely to experience meaningful and positive psychological states at work. According to Fredrickson’s theory, these states broaden individuals’ momentary thought–action repertoires, leading to the accumulation of psychological resources. Empirical research supports this perspective, showing that resilience predicts work engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment [

27,

28,

29]. These dimensions are essential for creating sustainable human resource systems.

H1a: Employee resilience is positively related to work engagement.

H1b: Employee resilience is positively related to job satisfaction.

H1c: Employee resilience is positively related to affective organizational commitment.

3.2. HAW and Grit

Fredrickson’s theory also suggests that repeated experiences of positive psychological states can build enduring motivational resources like grit. Work engagement, characterized by vigor and dedication, fosters goal-directed behavior and psychological resilience [

30]. Job satisfaction, when intrinsic, enhances commitment to goals through fulfillment and meaning [

31]. However, prior research also reveals counterarguments and mixed findings. Some studies suggest that high job satisfaction can, in certain contexts, reduce striving for achievement and persistence, a phenomenon referred to as the comfort zone effect, where employees who feel content with current conditions may lower their drive for long-term, challenging goals [

32,

33] Similarly, if satisfaction is primarily extrinsically driven (e.g., pay stability, favorable conditions), it may lead to motivational crowding-out, where intrinsic motivation is diminished [

34,

35,

36]. These contrasting perspectives indicate that the relationship between job satisfaction and grit is not universally positive but may depend on the nature and source of satisfaction. Considering these mixed findings, this study tests whether job satisfaction is positively associated with grit in a high-pressure service context.

Affective commitment strengthens identity-based motivation and sustained effort due to alignment with organizational values [

37]. Together, these elements are expected to influence grit positively.

H2a: Work engagement is positively related to grit.

H2b: Job satisfaction is positively related to grit.

H2c: Affective organizational commitment is positively related to grit.

3.3. Resilience and Grit, with HAW as a Mediator

Resilience provides the emotional stamina and psychological strength necessary to persevere, and grit represents a behavioral manifestation of these qualities over time [

38]. Fredrickson’s theory implies that resilience contributes to grit more effectively when filtered through enriching workplace experiences. Thus, HAW dimensions may mediate the effect of resilience on grit by fostering positive emotional contexts that allow goal persistence to thrive.

H3: Employee resilience is positively related to grit.

H4a: The relationship between resilience and grit is mediated by work engagement.

H4b: The relationship between resilience and grit is mediated by job satisfaction.

H4c: The relationship between resilience and grit is mediated by affective organizational commitment.

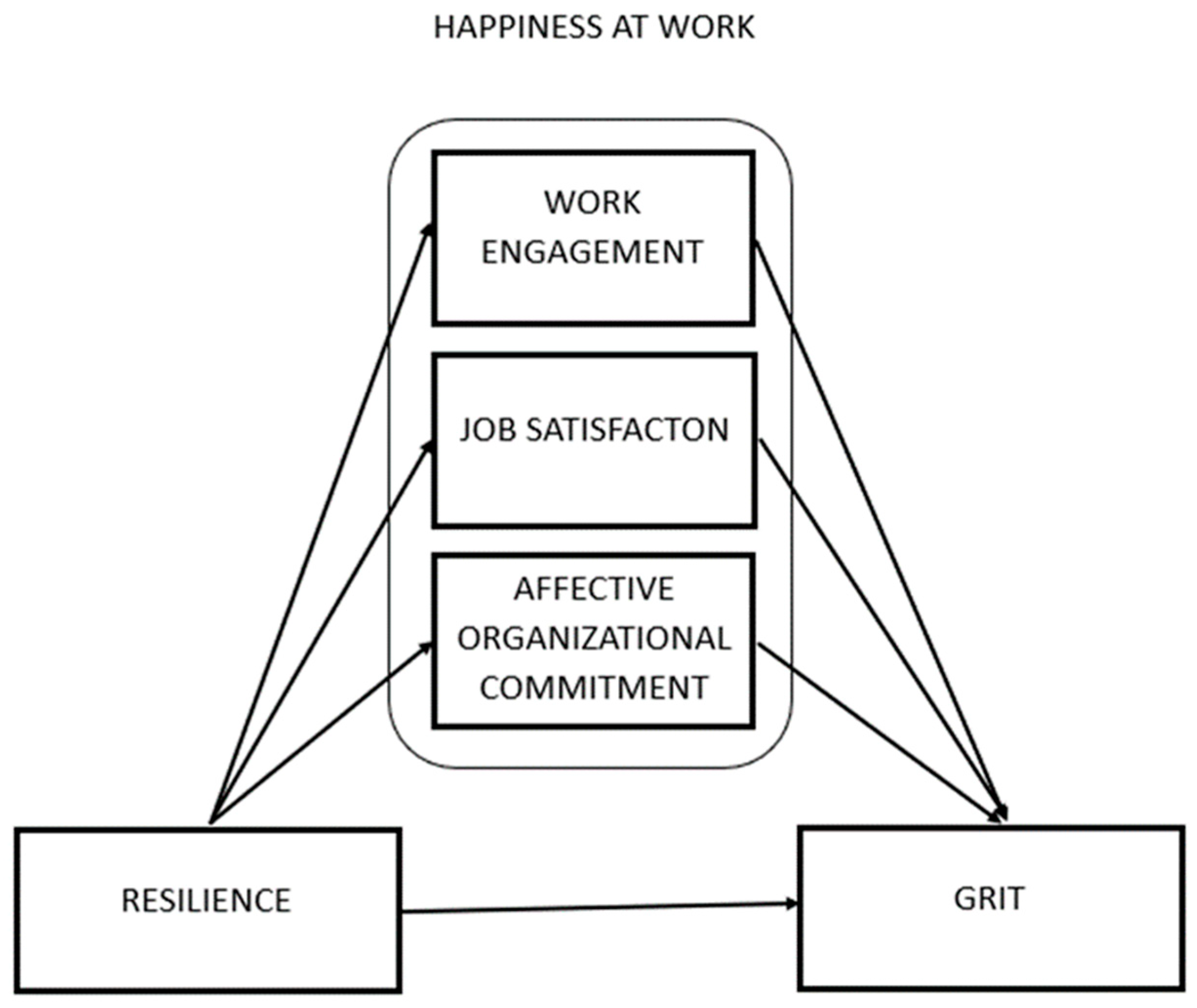

The conceptual framework capturing these proposed relationships is presented in

Figure 1.

4. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a quantitative research design to empirically examine how HAW, resilience, and grit interact to support employee well-being and psychological sustainability within the context of a high-pressure, essential service environment, an international airport.

4.1. Data Collection and Context

Data were collected from personnel at an international airport in Cyprus, an operational setting characterized by continuous service demands, public scrutiny, and safety-critical responsibilities. This context offers a relevant platform for exploring sustainable workforce strategies designed to enhance psychological resilience, commitment, and long-term perseverance. A total of 293 employees participated in the study, representing a diverse cross-section of operational roles, including security, ground handling, customer service, baggage logistics, maintenance, and administration, which were selected as strata for the stratified random sampling technique used to ensure representativeness, with a proportional allocation reflecting the actual workforce’s composition. The sampling frame was derived from the official employee roster provided by the airport administration to guarantee accuracy and transparency. The total population comprised approximately 425 ground and operations personnel employed across four airport terminals, resulting in a response rate of 68.9%. This response rate exceeds the minimum acceptable threshold for SEM studies, which is typically 200 respondents or a 10–20% response rate for populations under 1000 [

39,

40].

Recruitment was conducted via internal communication channels (email announcements, physical notice boards), with periodic reminders emphasizing the importance of the study for workplaces’ sustainability and well-being. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained throughout, in line with ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

We acknowledge the limitation of using a single airport sample for generalizability. However, this airport acts as a representative microcosm of high-pressure, safety-critical, and service-intensive organizations, with a diverse workforce across multiple roles supporting the examination of psychological constructs.

Therefore, the internal validity of the sample is strong for this context, although extrapolation to other organizations should be made cautiously. We recommend future research to replicate and extend these findings in different geographic and organizational settings to confirm their broader applicability.

4.2. Measures and Instruments

The survey instrument incorporated three validated scales widely used in organizational psychology:

Happiness at Work (HAW): Measured using the SHAW Scale developed by Salas-Vallina and Alegre [

17], which captures three dimensions: work engagement, job satisfaction, and affective organizational commitment.

Resilience: Assessed using the Workplace Resilience Scale created by Jefferies, Ungar, and Liebenberg [

41], which measures adaptability and recovery from occupational stressors.

Grit: Measured using the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S) by Duckworth and Quinn [

38], which evaluates sustained effort and passion toward long-term goals.

Sample items included the following:

HAW: “I feel a sense of joy and satisfaction in my job.” “I am motivated and engaged at work.”

Resilience: “I can quickly recover from difficult situations at work.”

Grit: “I maintain my focus on tasks even when faced with setbacks.”

These instruments were selected for their strong psychometric properties and demonstrated cross-cultural reliability, making them appropriate for use in diverse, international workplace contexts.

To ensure each instrument’s relevance and clarity for the target workforce, the survey was carefully translated and culturally adapted using a rigorous translation and back-translation process, maintaining conceptual equivalence and cultural appropriateness.

Details regarding the psychometric evaluation of these instruments, including factor loadings, construct reliability, and validity tests, are presented in

Section 5.1.

4.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SmartPLS 4, a variance-based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique particularly suited for small to medium sample sizes, models involving second-order constructs, and complex mediation structures [

42]. The analysis proceeded in four phases: (1) evaluation of the measurement model, (2) assessment of global model fit, (3) validation of the second-order construct for Happiness at Work (HAW), and (4) structural model testing, including mediation effects.

Measurement model assessment confirmed the reliability and validity of all constructs. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.747 to 0.940, and composite reliability (CR) values exceeded the recommended 0.70 threshold. Convergent validity was supported, with average variance extracted (AVE) values ranging from 0.638 to 0.882. No multicollinearity issues were observed, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 5. Discriminant validity was established using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), with all HTMT values falling below the conservative cutoff of 0.85.

Global model fit was evaluated using the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and related fit indices. The saturated model yielded an SRMR of 0.070, indicating an acceptable fit [

38]. Additional fit indices further supported the model’s adequacy: Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.811, d_ULS = 1.343, and d_G = 0.649 (see

Table 1).

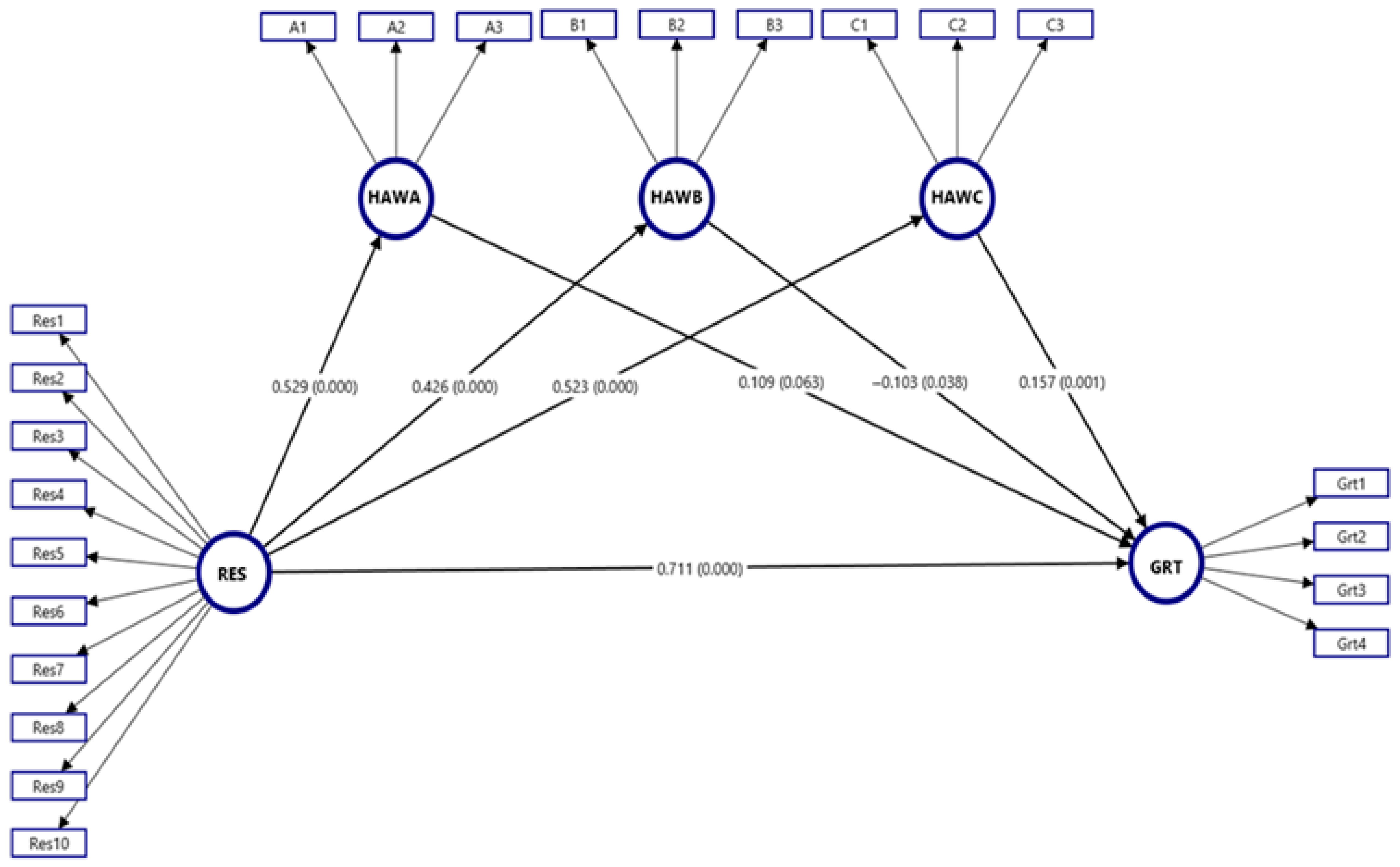

To validate the second-order reflective structure of HAW, comprising engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment, second-order confirmatory factor analysis was performed using both the repeated-indicator and two-stage approaches in SmartPLS. In both models, all first-order constructs significantly loaded onto the second-order construct (β = 0.808–0.885,

p < 0.001), supporting the conceptualization of HAW as a multidimensional latent construct. Fit indices also confirmed the model’s adequacy in both approaches (

Figure 2).

The structural model was then tested to examine direct effects of resilience on grit and the three HAW components, as well as indirect effects through the HAW dimensions. Path coefficients and significance levels were estimated using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples, generating bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. The results revealed a significant partial mediation effect, whereby affective commitment served as the key conduit linking resilience to grit, consistent with Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build Theory.

This stepwise analytical strategy provided a comprehensive understanding of how psychological resources interact to enhance sustainable employee well-being in a high-pressure, safety-critical service setting.

4.4. Participant Demographics

Among the 293 respondents, 74.1% were male (n = 217), 24.9% were female (n = 73), and 1% chose not to disclose gender. A total of 87.4% were full-time employees, while 12.6% were part-time. All participants completed the survey on-site during regular working hours at their respective duty locations. This demographic variation enhances the generalizability of the findings across multiple job roles and employment arrangements within the service-intensive, high-stakes airport environment.

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

Before testing the structural hypotheses, the measurement model was evaluated for reliability and validity. All constructs demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha (α) values ranging from 0.747 to 0.940, and composite reliability (CR) values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. Convergent validity was supported, as all average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.50 (see

Table 1).

To determine whether work engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment could be modeled as indicators of a higher-order construct (HAW), a second-order confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using both the repeated-indicator and two-stage approaches in SmartPLS. As shown in

Figure 2, all three first-order constructs significantly loaded onto the second-order HAW construct (β = 0.808–0.885,

p < 0.001), confirming its multidimensional nature. For robustness, the two-stage model was also tested, yielding comparable results (see

Figure 2).

Global model fit indices further supported the adequacy of the measurement model (see

Table 2).

5.2. Structural Model Evaluation

The structural model was assessed using standardized path coefficients (β),

t-values, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and

p-values obtained through bootstrapping (5000 resamples). All Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below the recommended threshold of 5, indicating no multicollinearity concerns (

Table 3).

The model showed a satisfactory fit (SRMR = 0.070). R

2 values indicated that the model explained 67.7% of the variance in grit, 28.0% in affective commitment, 20.9% in work engagement, and 18.1% in job satisfaction (

Figure 3).

Structural path results are presented in

Table 4. Resilience significantly predicted all three components of HAW and grit. Among the HAW components, only affective commitment significantly and positively predicted grit. Job satisfaction showed a small but statistically significant negative effect. Work engagement showed a positive, but non-significant, relationship with grit.

5.3. Mediation Analysis

Mediation was tested using bootstrapped indirect effects (5000 samples). Confidence intervals were used to determine significance. The total indirect effect of resilience on grit was significant (β = 0.073,

p = 0.011), supporting partial mediation through the components of HAW (

Table 5).

Affective commitment (HAWC) significantly mediated the resilience–grit relationship. Mediation through job satisfaction was marginally negative, and engagement approached significance but did not reach the statistical threshold.

These results confirm that while resilience directly predicts grit, it also exerts an indirect effect via affective commitment. The negative association between job satisfaction and grit may reflect that satisfaction alone, particularly when extrinsically derived, is insufficient to sustain goal-directed perseverance in high-pressure service environments.

6. Discussion

This study examined the role of resilience and HAW, conceptualized as a higher-order construct comprising work engagement, job satisfaction, and affective commitment, in fostering grit among employees in a high-pressure airport environment. Grounded in Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions, the findings offer important insights into how psychological resources and workplace experiences translate into sustained perseverance and long-term motivation. These insights are especially critical in safety-sensitive contexts such as airports, where employee grit directly affects operational safety, customer satisfaction, and organizational resilience during crises.

Among all predictors, resilience emerged as the most powerful determinant of grit (β = 0.711, p < 0.001), highlighting its central role in maintaining performance under pressure. This finding aligns with prior research linking resilience to adaptive capacity, self-regulation, and goal persistence in challenging work settings. For practitioners, this underscores that building resilience is not merely a wellness initiative; it is a strategic investment in operational continuity, especially in high-stakes industries.

The validation of HAW as a second-order reflective construct provides a more integrated yet differentiated view of employee happiness in the workplace. While the confirmatory factor analysis supports treating HAW holistically, the distinct effects of its components on grit reveal that these dimensions do not operate uniformly.

Affective commitment was the only HAW dimension that positively and significantly predicted grit (β = 0.157,

p = 0.001). This supports the notion that emotional attachment and identification with the organization fuel goal-directed perseverance, particularly in high-pressure contexts. Fostering a sense of meaning and belonging appears to be critical for sustaining employees’ effort and reliability [

13,

44].

Job satisfaction, in contrast, showed a small but significant negative association with grit (β = −0.103,

p = 0.038), contrary to expectations. One explanation is motivational crowding-out, where satisfaction primarily derived from extrinsic factors (e.g., pay stability, predictable schedules, favorable conditions) reduces the intrinsic drive necessary for the sustained pursuit of goals [

34,

35,

36]. A second possibility is the comfort zone effect, in which high satisfaction with current conditions decreases the perceived need to exert additional effort or persist through challenges [

32,

33]. This may be particularly relevant in high-pressure airport operations, where meeting immediate operational requirements could satisfy employees enough to lower their appetite for further challenge-seeking behaviors. Another explanation relates to context-specific role demands: in safety-critical environments, employees who are satisfied with meeting established performance standards may focus on maintaining, rather than exceeding, those standards, resulting in lower observable grit. While plausible, these interpretations remain speculative given the absence of direct measures distinguishing intrinsic versus extrinsic sources of satisfaction or differentiating satisfaction subdimensions (e.g., compensation, job meaning, autonomy). Future research should examine these mechanisms explicitly, using multidimensional job satisfaction measures and exploring how they interact with perseverance-related outcomes.

Work engagement showed a positive but non-significant effect on grit (β = 0.109, p = 0.063), suggesting that while engagement may energize employees in the moment, it may lack the emotional anchoring needed to convert short-term vigor into sustained grit unless paired with deeper forms of motivational investment, such as affective commitment.

These findings reinforce the importance of distinguishing between hedonic (e.g., satisfaction) and eudaimonic (e.g., commitment) forms of workplace well-being [

45]. While the CFA results statistically support modeling HAW as a higher-order construct, the divergent predictive effects of its components suggest unique psychological mechanisms are at play. This supports a dual approach in future research and practice: analyzing HAW both as a composite indicator and through its individual dimensions, especially in complex or high-stress work environments.

Importantly, affective commitment significantly mediated the relationship between resilience and grit (β = 0.082,

p = 0.002). This pathway confirms that emotional connection to the organization is not only an outcome of resilience but also a mechanism through which it is channeled into perseverance. This supports the broaden-and-build hypothesis within an organizational context, where emotionally supportive work environments both buffer stress and build motivational infrastructure for sustained performance [

19].

Mediation effects via job satisfaction and engagement were not significant. The marginally negative effect of job satisfaction may imply that high satisfaction, when not accompanied by emotional engagement or commitment, may actually reduce the urgency or drive to persist through difficulty. Engagement, while energizing, may require a complementary emotional base, such as purpose or identification with the organization, to translate into grit.

7. Theoretical Contribution

This study advances the field by empirically demonstrating how key psychological resources, HAW, resilience, and grit, interact as part of an integrated model within a real-world, safety-critical context. First, while these constructs are often studied in isolation, this research shows that sustainable performance in arduous settings requires their interplay. In particular, resilience is reconceptualized not merely as a personality trait or moderator but as a central mediating mechanism channelling workplace happiness into sustained goal-directed behavior (grit). This challenges purely individualistic views and instead positions resilience as a resource that can be systemically developed through organizational practices.

Second, this study contributes a nuanced theoretical distinction between the components of HAW, showing that not all well-being interventions will produce the same outcomes. Hedonic (satisfaction-focused) and eudaimonic (commitment and purpose-focused) well-being exert significantly different, and sometimes opposite, influences on grit. This insight compels future researchers and practitioners to tailor interventions, designing programs that promote deeper, meaningful person–organization connections rather than one-size-fits-all satisfaction efforts.

Third, applying this model in the airport sector demonstrates that human sustainability is a non-negotiable pillar of operational resilience. Grit here emerges not just as a personality dimension but as a critical factor underpinning safety, reliability, and adaptive capacity, key performance outcomes in aviation and other infrastructure sectors. This evidence provides a new, actionable framework for both scholars and practitioners working to marry human well-being with mission-critical results.

Ultimately, this research expands the conversation on sustainable workplace well-being by integrating individual psychological strengths with organizational design. It highlights that investing in psychological resources is not only a matter of employee welfare but a strategic imperative, especially in sectors where human adaptability and emotional regulation directly affect mission success.

8. Practical and Theoretical Implications

This study provides both practical insights and theoretical advancements relevant to organizations operating in high-pressure, emotionally demanding environments, particularly within the aviation and transportation sectors, where sustained employee performance is essential for safety, service quality, and organizational resilience. In practical terms, these findings serve as a blueprint for executives and HR teams seeking to build not only a satisfied but also a psychologically robust and performance-oriented workforce.

The strong predictive role of resilience highlights the need to shift from reactive stress management toward proactive cultivation of psychological resources. Rather than treating resilience as a trait to be managed post-crisis, organizations should embed it within their systems and culture. For airport environments, this translates into clear actions: develop tailored resilience training for operational staff (e.g., ground handling, security), incorporate resilience-based metrics into regular performance appraisals, and use real-life scenario training to strengthen adaptive capacity for frontline roles. More broadly, resilience can be fostered by promoting psychological safety, employee autonomy, reflective practices, and a growth-oriented mindset around stress and challenges.

This study identifies affective organizational commitment as a pivotal mediator in transforming resilience into grit. Emotional attachment to the organization fosters identity alignment and purpose, which in turn fuels goal persistence in the face of adversity. Airports and similar organizations can apply this insight by designing onboarding and communication programs that connect personal roles to broader organizational missions, implementing peer recognition systems tied to safety-critical behaviors, and conducting purpose-themed briefings that frame routine tasks in terms of public value and mission alignment. Opportunities for cross-role collaboration and structured mentoring may also enhance commitment, especially in shift-based or rotational roles.

Finally, the negative association between job satisfaction and grit prompts a re-evaluation of typical reward-based incentive structures. HR teams should focus on expanding non-monetary motivation programs, such as providing frontline staff with opportunities to lead improvement initiatives, rotating employees across functions for skill development, and encouraging contributions to safety committees, approaches that satisfy competence and relatedness needs without relying solely on monetary incentives. Skill mastery tracks, job enrichment, and meaningful recognition programs should also be prioritized over extrinsic rewards like salary or titles, particularly in safety-sensitive positions where grit and persistence are critical.

These results matter, because they provide a targeted, evidence-based roadmap for organizations to cultivate human sustainability, a critical ingredient for performance, safety, and resilience in modern, high-pressure workplaces. By integrating these insights, leaders can foster environments where both individuals and organizations thrive, even under the most demanding conditions.

9. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study advances our understanding of how resilience and multidimensional HAW contribute to grit, several avenues remain for further exploration. First, the sample exhibited a notable gender imbalance, with approximately 74% of respondents identifying as male. While this may reflect the workforce’s composition in the aviation sector, particularly in operational and technical roles, it limits the generalizability of the findings across genders. Future studies should aim to ensure more balanced or stratified samples to explore whether the observed psychological mechanisms differ by gender.

This study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to establish causality. Future research should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to capture the evolution of these psychological constructs over time. In particular, it would be valuable to investigate how resilience and grit interact dynamically under prolonged stress, changing management processes, or crisis events, conditions under which psychological endurance may be both tested and transformed.

The focus on the airport industry provides important insights into high-pressure service settings, but the model’s generalizability should be tested across other mission-critical sectors. Future studies could examine healthcare, emergency response, military service, or educational institutions, where both resilience and sustained effort are crucial for maintaining employee well-being and organizational performance. Furthermore, the research was conducted within a specific national and organizational context, which may influence how resilience, workplace happiness, and grit are perceived and enacted. Future studies are encouraged to examine whether these psychological mechanisms operate similarly across diverse cultural, institutional, and labor environments. Expanding the model to include moderating variables would offer greater explanatory power. Variables such as leadership style, team climate, and Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) configurations [

46] may help identify under which conditions resilience and workplace happiness are most likely to foster grit. These contextual buffers or amplifiers could reveal important boundary conditions for the framework.

Furthermore, although our second-order CFA supported the higher-order structure of HAW, the inconsistent paths to grit across its dimensions raise questions about its theoretical coherence. Future studies are encouraged to explore whether HAW functions better as a formative or multidimensional construct rather than a reflective latent factor.

Finally, future studies could adopt a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative models with qualitative techniques such as in-depth interviews, narrative inquiry, or diary studies. These methods would provide richer insights into how employees subjectively experience resilience and grit, and how organizational practices such as feedback quality, purpose framing, and value alignment contribute to the development of these psychological resources.

Ultimately, by integrating resilience and the multidimensional construct of workplace happiness within the broaden-and-build framework, this study presents a holistic and empirically testable model of how emotionally supportive workplace environments promote long-term perseverance. Future research is encouraged to move beyond narrow measures of employee satisfaction and toward strategies that intentionally cultivate affective commitment, intrinsic motivation, and resilience, the psychological building blocks of sustainable organizational performance.

10. Conclusions

This study deepens our understanding of how resilience and multidimensional HAW contribute to the development of grit in high-pressure, emotionally demanding environments. Grounded in Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build Theory, the findings demonstrate that resilience plays a pivotal role in sustaining long-term effort, both directly and indirectly through affective organizational commitment. Among the components of HAW, affective commitment emerged as the most robust predictor of grit, while job satisfaction showed a negative association, indicating that not all forms of workplace happiness contribute equally to sustainable motivation.

By conceptualizing HAW as a higher-order construct and examining its distinct pathways to grit, this research advances beyond traditional models that treat happiness, resilience, and grit as static or isolated traits. Instead, it positions them as dynamic, interdependent psychological resources that can be intentionally cultivated through strategic organizational design. This study underscores that emotionally enriching workplace experiences, particularly those that foster identity alignment and relational commitment, are central to building psychological capacities that support sustained performance.

Ultimately, this research affirms the strategic importance of fostering emotionally resilient and affectively committed workforces. These are not only vital for the flourishing of individuals but also for enhancing organizational adaptability, service consistency, and long-term success, all of which are essential elements of sustainable workforce systems. The model presented here offers a practical and empirically grounded foundation for organizations seeking to align employee well-being with performance sustainability in complex and high-stakes operational settings.