1. Dyads of Leaders’ StaffCare and Employees’ SelfCare

Leadership influences employees’ health by shaping workplace structures, setting workplace demands, delegating tasks, and providing resources within the organization [

1,

2]. The Health-oriented Leadership (HoL) framework integrates leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare as complementary components of health-centric leadership. By supporting others’ health (StaffCare) and maintaining one’s own (SelfCare), HoL contributes to reduced stress and improved well-being at work [

3].

Two pathways are distinguished through which StaffCare can impact employee health. First, leaders can directly influence their employees’ health by actively reducing employees’ demands (e.g., by optimizing working conditions, work routines, and work–life balance), making sure that the topic of health receives sufficient attention, or fostering positive interactions and respectful communication [

3,

4,

5]. Second, StaffCare can operate through an indirect pathway via employees’ SelfCare [

3,

4,

6,

7], which in turn improves employee health. This indirect pathway occurs as leaders raise awareness for health among their employees and encourage them to take proactive steps toward improving their health. This can include participating in occupational health promotion initiatives, such as attending back fitness courses, walking groups, and other health-related measures (e.g., active breaks, avoiding excessive overtime). Both the direct influence of StaffCare on health [

3,

5,

6] and the indirect influence of StaffCare on health through SelfCare have been empirically demonstrated [

4,

7,

8]. There is ample evidence for the relationship between leaders’ StaffCare and employee SelfCare [

4,

9,

10], indicating that low StaffCare is often associated with low SelfCare, moderate StaffCare with moderate SelfCare, and high StaffCare with high SelfCare. Actively engaging in StaffCare and health promotion typically results in higher SelfCare among employees. Conversely, neglecting StaffCare and exhibiting behaviors that endanger health tend to result in lower employee SelfCare. Although the correlation is substantial [

4,

9], it is far from perfect. This indicates the existence of deviant or inconsistent dyads, raising the question of whether there are relevant groups with systematic inconsistencies.

Overall, the question arises about whether there could be systematic groups that represent these inconsistent dyads and complement the previous prototypes of consistent relationships between StaffCare and SelfCare (low/low, moderate/moderate, high/high). Therefore, we may find at least two consistent prototypes as well as at least two inconsistent dyad forms that have not been previously identified. To uncover these potential inconsistencies and profiles, we used a person-centered approach, which is increasingly prevalent in empirical research [

10]. If these systematic inconsistencies exist, it also raises the question of whether there is a difference in health or other work-related outcomes based on group membership (e.g., high StaffCare and high SelfCare or high SelfCare despite low StaffCare) or if it makes no difference. Therefore, we measured health and motivation-related outcomes again three months later. If there is a difference with regard to outcomes, it becomes even more critical to determine which antecedents may predict membership in which dyad group. For example, this could be due to workplace resources or demands that affect both leaders and employees. In the context of new hybrid work models and digital collaboration, the factor of working from home (WFH) may be relevant. WFH could decrease StaffCare but promote SelfCare, thereby increasing the probability of the specific inconsistent pattern (low StaffCare, high SelfCare).

This study contributes to the research field of Health-oriented Leadership by exploring possible systematic inconsistencies in the dyadic relationships between leader StaffCare and employee SelfCare. To date, aside from Klug and colleagues, no other studies have further explored inconsistent dyads in HoL. This could shed light on the unexplained variance in the moderate correlation between StaffCare and employee SelfCare. Furthermore, by using the method of Latent Profile Analysis, this study aligns with and contributes to the growing field of person-oriented research within occupational health psychology. Unlike traditional approaches that examine relationships between variables, person-oriented research focuses on identifying patterns and profiles that illustrate how multiple factors interact within individuals [

10,

11,

12,

13].

The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model explains employee well-being and performance through two processes: job demands contribute to strain and health impairment, while job resources foster motivation, engagement, and buffer the negative impact of demands [

14]. By investigating specific work conditions, including job resources, such as WFH, and job demands, as predictors for different leader–employee dyads, this research broadens our understanding of the antecedents affecting StaffCare and SelfCare behavior within HoL [

6,

9,

15]. Currently, research has begun to examine Health-oriented Leadership within digital work environments, but it is still in its early stages and has not yet been comprehensive. Our study examines whether inconsistent dyadic relationships between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare emerge within hybrid working contexts and whether these relationships are influenced by factors such as increased working-from-home (WFH) days. This research also provides new insights into how inconsistent dyads impact health and other work-related outcomes [

3,

4,

7,

16].

Although inconsistent dyads have not been considered in the past, knowing about them may hold critical practical implications. It is always crucial to promote StaffCare within the framework of HoL through leadership training programs. However, it cannot be assumed that high StaffCare automatically leads to SelfCare. Instead, the implementation of SelfCare may be hindered and not executed, which can be due to overwhelming workloads. Therefore, it is crucial to pay attention to possible stressors, identify their causes, and implement countermeasures. Despite fewer leaders’ StaffCare, some employees manage to take care of themselves and achieve high SelfCare. This indicates that SelfCare can exist independently. Therefore, it also makes sense to directly promote occupational health measures to ensure that employees have the resources and support they need to maintain their health. These efforts can lead to a healthier, more committed workforce, benefiting both individuals and the organization.

2. Health-Oriented Leadership

The Health-oriented Leadership (HoL) concept represents an important advancement in understanding how leadership can promote employee health [

3]. It has been shown to enhance health outcomes more effectively than traditional leadership styles [

8]. Within the HoL concept, a distinction is drawn between the components of StaffCare and SelfCare, each addressing different perspectives of health orientation within the workplace.

StaffCare involves how leaders foster their employees’ health by promoting health-enhancing behaviors. This dimension of StaffCare is multifaceted, incorporating cognitive, affective, and behavioral elements. It involves valuing and prioritizing health, being aware of potential health risks and early warning signals, and engaging in health-promoting behaviors. Importantly, StaffCare also includes leaders’ role modeling of health-oriented practices, as employees tend to mirror their leaders’ behaviors. These behaviors include encouraging a healthy lifestyle (e.g., promoting physical activity), adopting health-promoting practices (e.g., providing access to mental health resources), and reducing health-endangering activities (e.g., minimizing overtime to prevent burnout or discouraging the habit of eating lunch at one’s desk [

3]).

SelfCare focuses on followers managing their own health, emphasizing personal responsibility and proactive steps to enhance and maintain it. It encompasses the value employees place on their own health, the awareness of their health status, stressors, and warning signals, as well as behaviors that support personal health. These behaviors include adopting a healthy lifestyle, engaging in health-promoting activities such as taking regular breaks, and avoiding health-endangering behaviors, including neglecting physical activity [

3,

5,

6].

Within the concept of HoL, two pathways are distinguished through which leaders’ StaffCare can impact employee health. The first pathway describes the direct influence of leaders’ StaffCare on their employees’ health [

3,

4,

5]. The second pathway is indirect, where StaffCare impacts employee health through employees’ own SelfCare. In this pathway, leaders create an environment that encourages employees to take proactive steps toward their own health [

3,

4,

6,

7]. Both pathways, including the direct influence of StaffCare on health [

3,

5,

6] and the indirect influence of leaders’ StaffCare on health through employees’ SelfCare [

4,

7,

8], have been demonstrated in various empirical studies.

2.1. Profiles of Dyadic Relationships Between Leaders’ StaffCare and Employees’ SelfCare

Following the indirect pathway in the HoL concept, research has confirmed that leaders’ efforts to care for their employees’ health (StaffCare) are closely linked to how employees manage their own health (SelfCare), with moderate correlations of around 45 [

4,

9,

10]. This relationship can manifest in various patterns of dyads.

Low StaffCare is often associated with low SelfCare. When leaders neglect StaffCare and exhibit behaviors that endanger health, employees tend to display lower levels of SelfCare.

Moderate StaffCare is associated with moderate SelfCare. When leaders demonstrate moderate levels of StaffCare, employees typically show moderate levels of SelfCare.

High StaffCare is associated with high SelfCare. Leaders who actively engage in StaffCare and promote health typically observe higher levels of SelfCare among their employees.

This demonstrates that the degree of leaders’ StaffCare can influence their employees’ SelfCare. However, the moderate correlation between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare [

4,

9] also indicates that besides consistent dyads, other dyadic relationships between leaders and employees may exist. There may be relevant groups with systematic inconsistent relationships, for example, (1) lower employees’ SelfCare despite a high leaders’ StaffCare and (2) high employees’ SelfCare despite low leaders’ StaffCare.

In addition to the statistical variance, theoretical reasons for these inconsistencies can also be derived from previous research. First, there may be an inconsistent dyad characterized by low employees’ SelfCare despite high leaders’ StaffCare. In such scenarios, employees may be hindered from practicing SelfCare even when encouraged by their leaders. In alignment with the JD-R model, such dilemmas could arise in work environments with scarce job resources and high job demands, forcing employees to prioritize organizational needs [

1,

14]. Although StaffCare can be considered a resource [

17], pressing job demands may reduce awareness of health risks and leave little time for engaging in health-related activities (e.g., taking active breaks and avoiding excessive overtime). Consequently, employees may find themselves in a dilemma, having to balance conflicting job- and health-related priorities. This situation could unintentionally lead employees to prioritize short-term tasks and goals over their own SelfCare and long-term health.

Second, there could be a further inconsistent dyad where employees exhibit high SelfCare despite receiving low StaffCare from their leader. One reason for this could be that such leaders perceive health promotion as falling outside of their influence or control. Another reason for this dyad could be that employees can take charge of their own health independently. This might be due to their resilience in contrast to others. Resilience is an individual capacity of employees, referring to the ability to adapt to challenging events and maintain stable functioning even in the face of highly stressful situations [

18,

19]. These resilient employees likely actively maintain their SelfCare despite receiving low StaffCare. However, this scenario might only be possible in work environments with suitable conditions and resources, such as flexible working arrangements and supportive infrastructure [

14].

This raises the question of whether there are not only random occurrences of inconsistent dyads but rather systematic groups that represent these inconsistent profiles, existing alongside the consistent profiles of leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare (low/low, moderate/moderate, high/high). The person-centered approach, which focuses on identifying patterns and profiles within individuals rather than isolated variables, supports this idea by suggesting that such systematic groups could exist within the broader context of HoL.

To date, there has been no published research on possible inconsistent profiles in the dyadic relationship between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare. Only a study by Klug and colleagues took a person-oriented perspective in HoL and examined the relationship between leaders’ own SelfCare and their StaffCare toward employees, identifying two inconsistent leadership profiles within HoL. Besides consistent groups, they identified two meaningful inconsistent profiles, i.e., one group where leaders sacrifice their own SelfCare to benefit their employees through StaffCare (self-sacrifice) and another group of leaders who care for themselves but neglect their followers’ health (others-sacrifice) [

10]. However, no study known to us so far has focused on the dyadic interplay between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare. Addressing this gap is important, as such inconsistencies may reveal hidden risks or ambivalent dynamics that cannot be captured by studying each variable in isolation. Building on Klug and colleagues [

10], we expect to find at least two consistent profiles as well as at least two inconsistent profiles that have not been previously identified, leading to Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1. Distinct profiles of the dyad relationship between leader StaffCare and employee SelfCare can be identified, including (a) two consistent profiles characterized by consistent high or consistent low scores on both StaffCare and SelfCare, and (b) at least two inconsistent profiles, characterized by inconsistencies between StaffCare and SelfCare (high StaffCare and low SelfCare; low StaffCare and high SelfCare).

2.2. Consequences of Profile Membership

If systematically consistent and inconsistent profiles exist, it raises the question of whether group membership is associated with differences in health and other work-related outcomes, mainly since leadership styles have traditionally been assessed based on their effectiveness in influencing individual and job-related outcomes [

20,

21]. To date, the outcomes of inconsistent relationships between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare have not been thoroughly explored. However, a well-established understanding of the outcomes for consistent relationships within these dyads exists. Research has consistently shown that the positive effects of StaffCare include higher levels of health [

22,

23] and well-being [

7], as well as reduced levels of strain [

17], burnout and exhaustion [

4], and depression [

7]. Therefore, employees who experience high levels of StaffCare from their leaders tend to have more favorable health outcomes [

3,

22]. Additionally, these positive health outcomes have also been observed in connection with SelfCare [

6,

9].

Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory [

24,

25], individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect valued resources. Stress occurs when these resources are threatened or lost. Applying this perspective, it can be assumed that the consistent high dyads, where leaders provide strong StaffCare and employees actively engage in SelfCare, are likely to show the most favorable health outcomes. This is because both resources (leadership care and personal care) are being maximized, contributing to better resilience against job demands and stress. Conversely, consistent low dyads are likely to have the least favorable health levels. However, it is essential to explore the consequences of membership on the inconsistent profiles. The question may be raised as to whether a profile characterized by high SelfCare, or one marked by high StaffCare, results in more favorable health outcomes. It can be assumed that high SelfCare, as a direct and actively practiced behavior, may lead to more immediate health benefits, as employees take personal responsibility for their well-being and health. However, high StaffCare involves more indirect influences, where leaders promote and encourage health-promoting behaviors instead of directly enacting them. As a result, some of the potential benefits may be diluted during this transmission [

3]. Therefore, we believe that an inconsistent dyad with low StaffCare, but high SelfCare will yield more favorable health outcomes compared to an inconsistent dyad with high StaffCare but low SelfCare. By favorable health outcomes, we mean less psychological strain in terms of irritation and lower psychosomatic health complaints, which capture cognitive-emotional and physical strain reactions [

26].

Besides effects on health, previous research has also confirmed the positive effects of StaffCare on employee engagement [

6] and commitment [

4]. Focusing on motivational outcomes, engagement is generally understood as a positive, work-related state characterized by high levels of energy and dedication, which manifests in employees’ enthusiasm for their work and the sense of fulfillment they derive from it [

27,

28]. Commitment, on the other hand, refers to an employee’s emotional attachment and sense of loyalty to their organization [

29]. Based on this previous research, we anticipate finding the highest motivational outcomes in consistently high dyad profiles and the lowest in consistently low profiles. When comparing inconsistent profiles, we expect that employees in a dyad characterized by high StaffCare but low SelfCare, will still value their leader’s guidance and supportive behavior. Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) theory emphasizes the quality of the dyadic relationship between leaders and employees, while Social Exchange Theory highlights the role of reciprocal obligations in social interactions. By the Leader–Member Exchange theory and the foundational principles of Social Exchange Theory, this interaction between leaders and employees will enhance their relationship, motivating employees [

30] and strengthening their commitment [

31]. Additionally, SelfCare may have a lesser impact on motivational outcomes than on health outcomes. Therefore, we expect higher levels of engagement and commitment in an inconsistent dyad with high StaffCare but low SelfCare.

Conversely, employees in an inconsistent dyad characterized by low StaffCare and high SelfCare may feel neglected or unsupported by their leaders, which can adversely affect their relationship [

30]. This perceived lack of support and interaction might result in decreased engagement and commitment compared to the inconsistent dyad with high StaffCare but low SelfCare.

We aim to investigate the differences in health-related outcomes by examining employee strain and health complaints, as well as motivational factors, including engagement and commitment, across the possible dyads of leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare. As outlined before, we postulate the following:

Hypothesis 2a. Dyads with a consistent high profile (high StaffCare & high SelfCare) show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with a consistent negative profile (low StaffCare & low SelfCare).

Hypothesis 2b. Dyads with a consistent high profile (high StaffCare & high SelfCare) show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with an inconsistent profile.

Hypothesis 2c. Dyads with an inconsistent profile of low StaffCare and high SelfCare show more favorable health but lower motivational outcomes than those with an inconsistent profile of high StaffCare but low SelfCare.

Hypothesis 2d. Dyads with an inconsistent profile show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with a consistent negative profile (low StaffCare & low SelfCare).

2.3. Antecedents for Profile Membership

If there is a difference with regard to outcomes, it becomes even more critical to determine which antecedents predict the membership of the profiles. Several studies before have identified predictors of leaders’ StaffCare across different levels, including contextual, organizational, workplace, and individual factors [

32]. At the contextual level, external factors such as crisis conditions influence leaders’ StaffCare by posing additional challenges and hindering their ability to care for their employees’ health [

9]. At the organizational level, a positive organizational health climate can foster an environment where leaders are more likely to engage in StaffCare and support their employees [

6]. At the workplace level, in line with the JD-R model [

1,

14], job demands and job resources can play a crucial role [

15,

32]. Arnold & Rigotti demonstrated that interruptions and work-related problems can hinder leaders from effectively engaging in their StaffCare [

15]. But also, multitasking plays a critical role [

32]. Conversely, job resources such as delegation, autonomy, and support enable leaders to foster a health-promoting work environment and care for their employees [

32]. Lastly, at the individual level, strain is a significant predictor of StaffCare [

32]. Studies showed that high levels of strain can negatively impact a leader’s ability to engage in StaffCare behaviors [

33]. Therefore, certain predictors, such as job demands and resources, are known to affect leaders’ StaffCare.

Based on previous research, job demands and job resources might not only influence leaders’ StaffCare but also serve as predictors for profile membership. According to the JD-R model [

1,

14], a wide range of demands (e.g., workload, availability, overtime) and resources (e.g., autonomy, flexibility, social support, work–life balance, or organizational health initiatives) can play a role. However, in the present study, we focus explicitly on two job demands: constant availability through digital communication tools (also after work) and workload. Furthermore, we investigate three job resources: social support of colleagues, work–life balance, and the intensity of WFH. Given that many teams are currently working in hybrid or fully digital environments, research has shown positive effects of WFH on employees’ SelfCare and health [

34]. Specifically, WFH can provide additional autonomy and flexibility [

35,

36], thereby functioning as a resource for SelfCare. At the same time, it may also reduce access to important resources, such as less informal contact, less clarity of communication, and misunderstandings [

37,

38,

39], which highlights its potentially ambivalent role. Therefore, the intensity of days working from home could be another potential job resource influencing profile affiliation. These five factors were selected because they are highly relevant in the current hybrid and digitalized work environment and can be theoretically grounded in the JD-R framework. According to previous research, the highest job demands and poorest resources might predict membership in a consistently low profile, whereas optimal resources and lowest demands predict membership in a consistently high profile [

14,

40].

Hypothesis 3a. Employees of Dyads with a consistent profile of low StaffCare & low SelfCare show higher job demands and lower job resources compared to the profile of high StaffCare & high SelfCare as a reference group.

We assume that an inconsistent profile characterized by high leader StaffCare but low employee SelfCare may result from limited resources and higher job demands. Even though the leader may act in a health-oriented manner and try to promote well-being initiatives, employees might struggle to translate these efforts into concrete SelfCare practices. This could be due to an overwhelming workload that leaves no time for such activities [

41], or constant digital availability leading to technostress [

42], but also overtime after work hours, which hinders focus on personal health. If, on top of that, there is a lack of support from colleagues, and employees are left to handle tasks alone [

43]. Work can become overwhelming, ultimately leading to a poor work–life balance.

Hypothesis 3b. Employees of Dyads with an inconsistent profile of high StaffCare & low SelfCare show higher job demands and lower job resources compared to the profile of high StaffCare & high SelfCare as a reference group.

In contrast, when considering the possible inconsistent dyad characterized by high employees’ SelfCare despite low leaders’ StaffCare, it is possible that these employees can maintain high SelfCare despite low StaffCare due to more favorable job conditions. They may have a lower workload, possibly allowing more time for themselves and reducing the need for overtime or overwork [

41]. Additionally, limited availability, especially after work hours, may support their ability to disconnect and prevent the blending of work and personal life. Instead, they might achieve a better balance between work and personal life, which in turn allows them to schedule sufficient time for SelfCare activities, such as exercise classes, walks, or spending time with family and friends [

44]. In addition, support from colleagues can encourage employees to seek help when under time pressure or facing challenges, ensuring they are not left to handle difficulties on their own [

43].

Hypothesis 3c. Employees of Dyads with an inconsistent profile of low StaffCare & high SelfCare show lower job demands and higher job resources compared to the profile of low StaffCare & low SelfCare as a reference group.

Additionally, working from home (WFH) might be another critical double-edged antecedent. WFH presents unique challenges for leaders, often hindering their ability to maintain regular and effective communication with their teams, thus creating a sense of distance between leaders and employees [

37,

39,

45]. This dynamic can lead leaders to perceive health promotion as essential, but feel that they have less influence over their employees’ well-being in a WFH context [

46]. Consequently, they may adopt a more passive role, reflected in lower levels of StaffCare. In contrast, employees in this context may recognize the increased responsibility for their own health and take proactive steps to enhance their health [

34,

46]. In addition, the further benefits associated with WFH, such as greater flexibility, autonomy, time savings from reduced commuting, personalized working space, and more quiet time due to fewer interruptions, provide additional resources that employees can leverage to maintain or even enhance their health [

38,

47]. This may help explain why employees find it easier to maintain high SelfCare despite lower StaffCare in a remote work setting [

34]. Therefore, WFH may be more often found in dyads with low StaffCare and high SelfCare.

Hypothesis 3d. Employees of Dyads with an inconsistent profile of low StaffCare & high SelfCare show more WFH compared to the other profile groups.

4. Results

As illustrated in

Table A1 in the

Appendix A, the results show that leaders’ StaffCare is correlated with employees’ SelfCare dimensions. Specifically, employees’ SelfCare promotion correlates with reduced strain, fewer health complaints, and higher engagement, while SelfCare-endangering behavior correlates with increased strain and health issues. Job demands, like workload, negatively correlate with health-promoting behaviors and positively with strain, whereas job resources, such as social support and work–life balance, support health-promoting behaviors and reduce strain.

4.1. Identifying Dyads of Leaders’ StaffCare and Employees’ SelfCare

Table 1 shows the LPA results comparing models with two to seven latent profiles. Initially, we evaluated the two-profile model, which had very low VLMRT and LMRT significance. The three-profile model showed improved model fit, indicated by lower aBIC values and significant VLMRT/LMRT values. It also resulted in increased entropy, suggesting a better distinction between profiles. However, continuing to the four-profile model further improved logL and aBIC, with high entropy values and VLMRT/LMRT significance. These findings indicated that the four-profile model provides a superior fit to the three-profile model and offers more precise profile separation. In contrast, exploring profile solutions five, six, and seven showed only minimal improvements in logL and aBIC but no significant VLMRT and LMRT for the 5-profile solution. Therefore, profile solution four was selected to achieve the best balance between model fit and profile distinctiveness.

Figure 1 illustrates the mean scores for the subdimensions of leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare across the four distinct profiles.

The first profile comprises 10.7% of the sample and is characterized by consistently high scores in the subdimensions of awareness, lifestyle, and health-promoting behaviors, accompanied by low levels of health-risking behaviors. This pattern is observed in both Leaders’ StaffCare and Employees’ SelfCare. Therefore, this profile is labeled as Dyad of Health Promoters (HP).

The second profile comprises 22.4% of employees and exhibits the opposite pattern, with low scores in both leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare. It shows high levels of endangering behaviors and low levels of awareness, lifestyle, and health promotion on both sides, among leaders and employees. This profile is referred to as the Dyad of Health Compromisers (HC).

The third profile represents 32.3% of the sample and is characterized by high awareness but almost no health-promoting behaviors and no endangering behaviors, leading to generally lower leaders’ StaffCare ratings. Due to the absence of behaviors in either direction, we term them as Bystanding Leaders. However, this profile shows high employee SelfCare scores and proactive health-promoting behaviors among employees. Therefore, this profile is labeled as Dyad of Bystanders & Health Proactives (B&HP) and represents the expected inconsistent dyad of low leaders’ StaffCare and high employees’ SelfCare.

The fourth profile represents 34.6% of employees. It shows higher levels of StaffCare across awareness, lifestyle, and health-promoting behaviors, but also includes high levels of health-risking behaviors. These tendencies are also displayed in employees’ SelfCare, showing higher levels of awareness, lifestyle, and health-promoting but also self-endangering behaviors. Due to the strong presence of health-endangering behaviors, this profile is labeled as Dyad of Health-Sacrificers (HS). These patterns fit the inconsistent dyad of high leaders’ StaffCare (generally high levels across the subdimensions) and lower employees’ SelfCare.

In summary, this analysis identifies two profiles with consistently high as well as low levels of both leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare dyads and two additional profiles with inconsistent patterns. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

4.2. Differences Across Profile Membership

The ANCOVA results (in

Table A2 in the

Appendix A) show differences among the four profile dyads (of

Health Promoters,

Health Compromisers,

Bystanders & Health Proactives, and

Health Sacrificers) across both health and motivational outcomes after adjusting for gender and age.

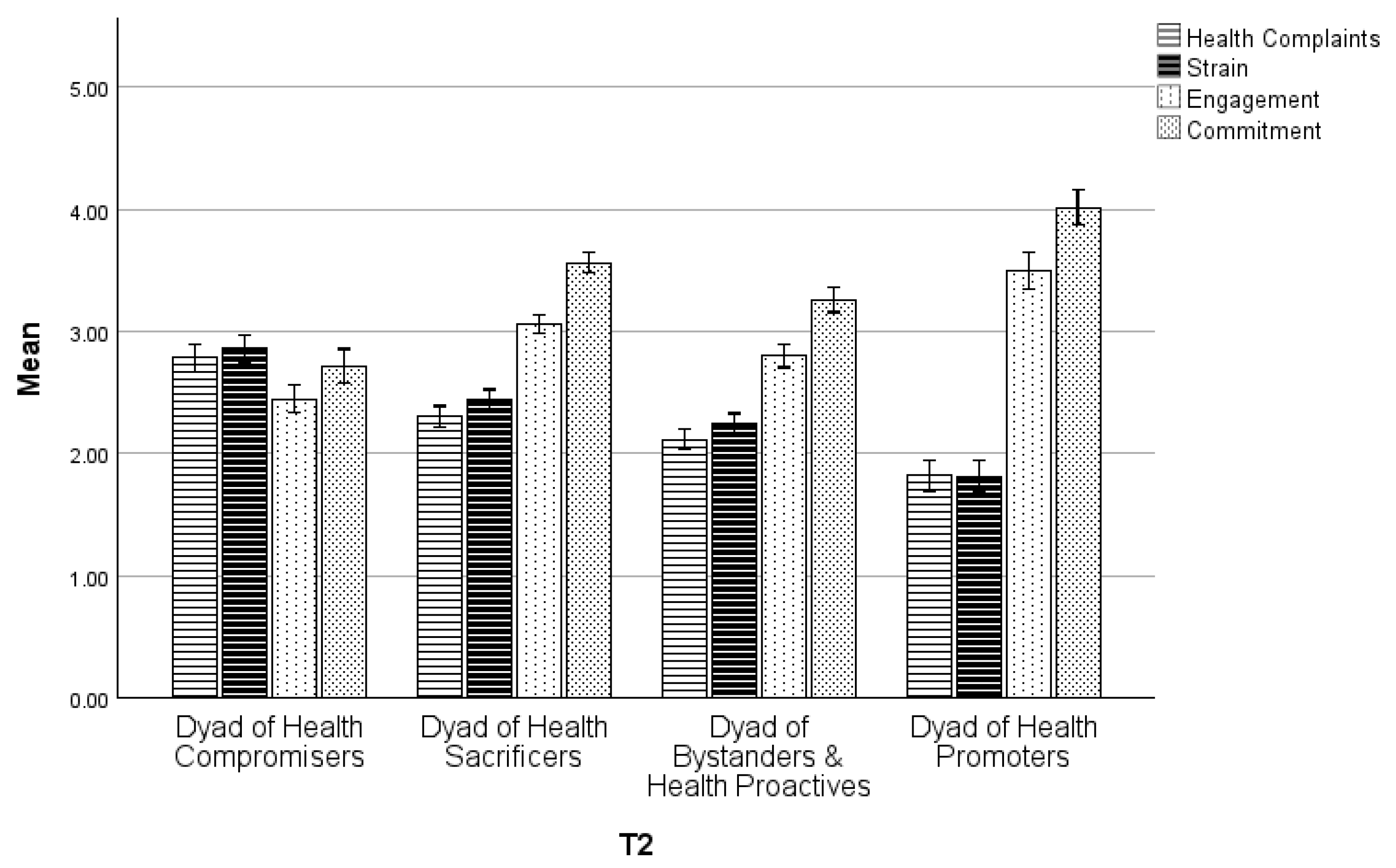

First, we expected dyads with a consistent high profile to show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with a consistent negative profile. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc tests show that employees in the Dyad of Health Promoters (HP) reported significantly higher health and motivational outcomes compared to Health Compromisers (HC). At T1, the Health Promoters (HP) showed lower strain (M [HP] − M [HC] = −1.10, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001), lower health complaints (M [HP] − M [HC] = −0.91, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), and also higher engagement (M [HP] − M [HC] = 1.04, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001), and higher commitment (M [HP] − M [HC] = 1.35, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001), These results were consistent and significant at T2. Therefore, Hypothesis 2a is supported.

Second, we expected dyads with a consistent high profile (Health Promoters [HP]) to show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with an inconsistent profile (Bystanders & Health Proactives [B&HP]: low StaffCare & high SelfCare; Health Sacrificers [HS]: high StaffCare & low SelfCare). At T1, participants of Health Promoters reported significantly lower strain compared to Dyad of Bystanders & Health Proactives (M [HP] − M [B&HP] = −0.49, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) and Health Sacrificers (M [HP] − M [HS] = −0.70, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) and lower health complaints (M [HP] − M [B&HP] = −0.29, SE = 0.08, p < 0.01; M [HP] − M [HS] = −0.48, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001). Additionally, the Health Promoters exhibited higher engagement (M [HP] − M [B&HP] = 0.71, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001; M [HP] − M [HS] = 0.46, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) and higher commitment (M [HP] − M [B&HP] = 0.82, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001; M [HP] − M [HS] = 0.57, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001) than in both inconsistent profiles. These trends were also significant at T2. Therefore, Hypothesis 2b can be supported.

Third, we expected the possible inconsistent dyad of low StaffCare and high SelfCare (Bystanders & Health Proactives [B&HP]) to show more favorable health but lower motivational outcomes than those with an inconsistent profile of high StaffCare and low SelfCare (Health Sacrificers [HS]). At T1, the participants of the Bystanders & Health Proactives had lower strain (M [B&HP] − M [HS] = −0.21, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01) and lower health complaints (M [B&HP] − M [HS] = −0.19, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01), but also lower engagement (M [B&HP] − M [HS] = −0.27, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001) and lower commitment (M [B&HP] − M [HS] = −0.25, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001) than the Health Sacrificers. These results were also significant at T2. Therefore, Hypothesis 2c can be supported.

Fourth, we expected dyads with an inconsistent profile (Health Sacrificers [HS]; Bystanders & Health Proactives [B&HP]) to show more favorable health and higher motivational outcomes than those with a consistent negative profile (Health Compromisers [HC]). At T1, the participants of the inconsistent dyads showed lower strain (M [HS] − M [HC] = −0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001; M [B&HP] − M [HC] = −0.61, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), lower health complaints (M [HS] − M [HC] = −0.44, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001; M [B&HP] − M [HC] = −0.62, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), and higher engagement (M [HS] − M [HC] = 0.59, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001; M [B&HP] − M [HC] = 0.33, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) and higher commitment (M [HS] − M [HC] = 0.79, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001; M [B&HP] − M [HC] = 0.53, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) compared to the consistent dyad of Health Compromisers. These results were also significant at T2. Therefore, Hypothesis 2d can be supported.

In summary, these results demonstrate that the profiles exhibit distinct patterns of strain, health complaints, engagement, and commitment at both time points, supporting the study’s hypotheses. Additionally,

Figure 2 provides an overview of the average scores for all health- and motivational-related indicators across the different profiles.

4.3. Predicting Profile Membership with Working Conditions

Using multinomial logistic regression, we analyzed whether working conditions, such as job demands (availability and workload), job resources (social support and work–life balance), and WFH intensity, could predict membership in one of the previously identified profiles. We also included age and gender as control variables. For Hypotheses 3a and 3b, we used the

Health Promoters (high StaffCare & high SelfCare) as the reference group. The results are presented in

Table A3 in the

Appendix A.

First, for Hypothesis 3a, we analyzed whether employees in the dyad of Health Compromisers (low StaffCare & low SelfCare) show higher job demands and lower job resources compared to the Health Promoters as the reference group. While workload is a positive predictor for Health Compromisers (B = 1.625, SE = 0.192, p < 0.001), availability is not (B = −0.048, SE = 0.146, p = 0.740). In contrast, more social support (B = −1.637, SE = 0.178, p < 0.001) and work–life balance (B = −0.787, SE = 0.194, p < 0.001) significantly reduce the probability of being in the dyad of Health Compromisers. Therefore, Hypothesis 3a can be mainly supported.

Second, for Hypothesis 3b, we expected employees in the dyad of Health Sacrificers (high StaffCare and low SelfCare) to show higher job demands and similar or lower job resources compared to the reference group of Health Promoters. Workload had a positive effect on Health Sacrificers (B = 1.120, SE = 0.174, p < 0.001), while availability had again no effect (B = 0.208, SE = 0.128, p = 0.105). In contrast, more social support was negatively associated with Health Sacrificers (B = −0.848, SE = 0.164, p < 0.001) and work–life balance (B = −0.614, SE = 0.185, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 3b can be mainly supported.

Third, for Hypothesis 3c, we expected employees in a dyad of

Bystanders & Health Proactives (low StaffCare and high SelfCare) to show lower job demands and higher job resources compared to the reference group of

Health Compromisers. The results are presented in

Table A4 in the

Appendix A. The dyad of

Bystanders & Health Proactives showed that workload was negatively associated (

B = −1.262,

SE = 0.130,

p < 0.05), while availability had no significant effect again (

B = −0.129,

SE = 0.105,

p = 0.221). On the other hand, they have more social support (

B = 0.597,

SE = 0.110,

p < 0.001) and work–life balance (

B = 0.309,

SE = 0.107,

p < 0.01) than the

Health Compromisers. Therefore, Hypothesis 3c can be mainly supported.

Fourth, for Hypothesis 3d, we expected employees in the dyad of

Bystanders & Health Proactives (low StaffCare and high SelfCare) to show more WFH than the other dyads. Therefore, we used the

Bystanders & Health Proactives as a reference group. The results are presented in

Table A5 in the

Appendix A. As expected, the dyads of

Health Compromisers (

B = −0.072,

SE = 0.059,

p = 0.226) and

Health Sacrificers (

B = −0.013,

SE = 0.053,

p = 0.806) showed fewer days WFH than the

Bystanders & Health Proactives. However, these results were not significant. The results for the

Health Promoters were not as expected, nor were they significant. They worked more days from home (

B = 0.082,

SE = 0.487,

p = 0.302) than the

Bystanders & Health Proactives. Therefore, Hypothesis 3d cannot be supported.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to identify possible systematic groups representing inconsistent dyads, complementing the established prototypes of consistent relationships between StaffCare and SelfCare. If such systematic inconsistencies existed, it is also crucial to examine differences in health and other work-related outcomes across these groups and to determine which antecedents may predict membership in each dyad.

In fact, we identified two consistent and two inconsistent dyadic relationships between leaders and their employees. In the following sections, we will discuss the characteristics and consequences of membership, as well as the conditions that may explain the occurrence of each profile. As expected, we found a

Dyad of Health Promoters in line with the HoL concept [

3]. This profile represents the notion that high levels of leaders’ StaffCare result in high levels of SelfCare in followers. This means that leaders’ awareness of health issues and support may encourage followers to engage in SelfCare. This profile had the most favorable health and motivational outcomes, which aligns with prior research [

3,

7,

10]. It also reaffirms that through the indirect pathway of StaffCare on SelfCare [

19], not only health but also employee engagement and commitment can be positively influenced [

15]. The success of this profile may be partly attributed to higher job resources (higher social support, work–life balance) and lower job demands (lower workload). These antecedents are crucial for leaders’ own SelfCare and, consequently, their StaffCare [

15]. They can now also be recognized as essential for the transition to employees’

SelfCare. Nevertheless, it is necessary to acknowledge that this group constitutes the smallest proportion of our sample. This may be due to poor job resources and high job demands. Still, it also suggests that while leadership behavior and favorable work conditions are essential, there may be unknown factors that prevent others from achieving this profile.

In contrast to the first profile, the other consistent

Dyad of Health Compromisers, characterized by low levels of both leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare, often engaged in health-endangering activities, which led to the least favorable health and motivational outcomes. This is, as before, in line with the HoL concept [

3], and prior research found that low StaffCare is associated with increased burnout and decreased job satisfaction among employees [

7,

56]. This profile suggests that low levels of leaders’ StaffCare lead to low levels of SelfCare among followers. A lack of health awareness and support may discourage followers from actively engaging in their own SelfCare. Interestingly, but also expected, this profile exhibits the highest job demands and lowest job resources. This suggests that working conditions, such as high job demands (high workload), may play a central role in fostering health-compromising behaviors among leaders and followers. Moreover, under these conditions, followers may not be able to demonstrate SelfCare despite their leaders’ poor StaffCare. Since working conditions are modifiable, work design should be a key element in workplace health interventions.

According to the HoL framework, additional consistent profiles with moderate levels of leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare could have been possible and plausible [

3], yet were not identified in this analysis. Instead, apart from the postulated positive relationship [

3], two further inconsistent profiles were identified and are new to current research. One of the inconsistent profiles we identified was the

Dyad of Health Sacrificers. We expected these leaders to exhibit high StaffCare, but followers to show poor SelfCare. High levels of StaffCare among these leaders were indeed reflected in their overall scores, yet a closer look at the subdimensions revealed a more complex picture. These leaders demonstrated strong awareness of risks and health-specific warning signals and actively supported their followers’ health, yet paradoxically also engaged in health-endangering behaviors at a high level. This contradictory behavior was obscured when examining only the overall StaffCare scores, as the high levels of awareness and health-promoting behaviors averaged out the health-endangering behaviors. Although we had anticipated that employees would exhibit lower SelfCare, we also observed higher levels of self-awareness and health-promoting behaviors, alongside high levels of self-endangering behaviors. This suggests that both leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare appear similar. However, the levels of subdimensions within profiles contradict each other, as both leaders and employees demonstrate high levels of health awareness and actively promote health, yet also engage in behaviors that endanger their own health. This contradiction seems strongly to influence employees’ SelfCare. This leads to all positive effects being neutralized by the health-endangering behavior, resulting in less favorable health outcomes, which manifest as higher levels of strain and health complaints compared to both

Health Promoters (high/high) and

Bystanders & Health Proactives (low/high). Interestingly, employees in this profile often face a high workload and potentially a high-pressure work environment, which may lead to tolerating or even considering health-endangering behaviors as necessary. This could explain why both leaders and their employees engage in these risky behaviors despite being aware of the associated health risks. Employees might acknowledge and appreciate their leaders’ efforts in health promotion, attributing the risky behaviors to external circumstances rather than leaders’ behavior. This perspective could explain higher levels of employee engagement and commitment than the

Bystanders & Health Proactives (low/high). In short, this suggests that occasional StaffCare-promoting behaviors strongly impact motivational outcomes, while occasional risk-taking behaviors undermine all efforts related to health outcomes.

The second unknown profile is the inconsistent

Dyad Bystanding Leaders & Health Proactives. These leaders, despite recognizing potential risks and warning signals, neither promote health measures actively nor encounter harmful practices or behaviors, overall, demonstrating lower levels of StaffCare. We anticipated that employees might still exhibit high levels of SelfCare despite low levels of StaffCare from leaders, which was indeed observed. Although the inconsistency between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare in this profile is as expected (low/high), an additional inconsistency emerges at the sub-dimensional level of StaffCare. Although they provide lower health promotion, leaders do not exhibit health-endangering behaviors within their StaffCare profiles. As a result, employees in this profile experience better health outcomes than

Health Sacrificers (high/low) but lower outcomes than

Health Promoters (high/high). However, their motivational outcomes are lower than those of both

Health Promoters (high/high) and

Health Sacrificers (high/low). Employees’ ability to benefit health-wise by practicing high SelfCare despite low StaffCare from their leaders may be due to the WFH context and favorable working conditions, such as a lower workload and more social support, as well as a better work–life balance than the

Health Sacrificers (high/low). The WFH context carries the risk that leaders shift responsibility for health promotion to employees, resulting in lower levels of StaffCare. This tendency was also observed in previous research [

46]. Accordingly, other studies have identified WFH as a significant predictor of improved SelfCare among employees and WFH intensity as positively influencing the effectiveness of SelfCare in improving health [

34]. However, our research did not find that the intensity of WFH days significantly influenced profile membership. Further analyses of working conditions indicate that in this dyad, job demands are low, and job resources are high. In particular, work–life balance as a job resource, combined with a low workload as a low job demand, supports employees in proactively managing their own SelfCare. A better work–life balance, which may be more easily achieved through WFH, suggests that the general availability of WFH could still play a role.

From the findings on consistent profiles and newly observed inconsistent dyads, one key interpretation can be derived: Our results align with previous research showing the strong connection between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare [

4,

9,

10], but more differentiated as seen before. Employees tend to mirror the behaviors of their leaders even on the subdimensions. Across all four dyadic profiles, employees replicated their leaders’ health-promoting or risk-taking behaviors. This mirroring effect can be attributed to leaders acting as role models in the workplace [

57]. When leaders demonstrate supportive behaviors, employees are likely to follow, especially when appropriate working conditions are present, enabling high SelfCare with minimal health risks. However, there are also crucial inconsistencies within leadership behavior (StaffCare). In one dyad, leaders recognize health risks and warning signals in their employees; however, they only provide minimal health promotion but refrain from health-endangering behaviors (as seen with

Bystanders & Health Proactives), whereas in the other dyad, leaders actively support health but still engage in endangering behaviors (as seen with

Health Sacrificers). Therefore, the varying levels of health-endangering behaviors in leaders’ StaffCare may be a key factor influencing followers’ SelfCare.

Health Proactives can maintain their SelfCare under

Bystanding Leaders who exhibit low levels of health-risking behavior, whereas

Health Sacrificers struggle to do so despite health promotion efforts, as the leaders’ health-endangering behaviors undermine these efforts. Interestingly, these health-endangering behaviors in leaders tend to emerge when employees perceive their work situation with high job demands, such as workload, and low job resources.

In summary, inconsistencies were found not only in the dyadic relationship between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare but also within leadership behavior at the subdimensional level. This inconsistent leadership behavior appears to depend on existing working conditions, which, in turn, can either hinder or support employees’ SelfCare and, therefore, individual outcomes.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, our findings on two consistent relationships strengthen the concept of HoL [

3], by confirming the relationship between leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare, further validating prior research [

4,

9,

10]. Additionally, our study expands the understanding of dyadic relationships between leaders and employees by not only identifying consistent dyads but also discovering two inconsistent dyads:

Health Sacrificers and

Bystanders & Health Proactives. This research on profile analysis also aligns with and contributes to the field of person-oriented research in HoL [

10] and occupational health psychology [

58] and expands previous research on consistencies within persons (i.e., leaders) by considering a dyadic perspective. Our results indicate that health-oriented behaviors such as StaffCare and SelfCare may add a valuable health-related dimension to leader-follower exchanges as described in LMX and Social Exchange Theory [

30,

31].

We also contribute further knowledge to the existing understanding of the indirect pathway in the HoL concept, confirming that leaders’ StaffCare can positively influence employees’ SelfCare and, in turn, improve health outcomes [

3,

8,

17,

59]. Our study shows that StaffCare impacts not only health outcomes but also motivational outcomes and therefore provides more empirical evidence for the effectiveness of HoL on motivational aspects. While it is known, and our findings confirm, that consistent relationships between leaders’ StaffCare and employee outcomes yield either high or low health and motivational results, we now show that inconsistent relationships also produce mixed results:

Bystanders & Health Proactives dyad leads to better health outcomes, while the

Health Sacrificers enhances motivational outcomes. This suggests that employees’ SelfCare can only succeed when leaders exhibit low levels of endangering behavior. Once risky behavior is present, it undermines health-promoting efforts, preventing effective SelfCare and resulting in poorer health outcomes. This pattern is also consistent with the Conservation of Resources Theory, which states that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect valued resources [

24,

25]. From this perspective, StaffCare and SelfCare can be understood as complementary resources within the dyad. When both are present at high levels, resources are accumulated and health outcomes improve, whereas self-endangering leadership behavior represents a resource loss that undermines employees’ SelfCare efforts. However, self-endangering behavior is not a determining factor for motivational outcomes, which is shown in higher levels of engagement and commitment in this profile.

Previous studies have primarily focused on examining leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare within traditional, on-site work environments, where regular face-to-face interactions are the norm. To date, only a few studies have explored StaffCare [

46,

60] and SelfCare [

34] in a digitalized work setting, such as WFH. Consequently, our research contributes not only to the growing body of literature on HoL in WFH contexts but also adds to the broader research on the benefits and challenges associated with WFH practices [

47,

61,

62]. In our research, we found that the intensity of days WFH is not a significant predictor of profile membership. This contrasts with previous research, which identified WFH as an important influential factor for employees’ SelfCare [

32,

34]. However, job demands, such as workload, and resources, such as work–life balance and social support, play a critical role. This pattern is in line with the JD-R model, which emphasizes that strain results from high job demands, whereas job resources can buffer these effects and foster motivation [

1,

14]. Therefore, our findings provide new insights into the antecedents of employees’ SelfCare, as previous research primarily focused on antecedents related to leaders’ SelfCare [

15,

32] and StaffCare [

9,

33]. This expands the understanding of how work conditions influence the level (i.e., whether high or low) of leadership behaviors and employees’ health-related outcomes.

5.2. Practical Implications

Recognizing these consistent and inconsistent dyads, leadership training programs should help leaders understand the impact of their role within the occupational health promotion [

23,

57]. Previous research has demonstrated that Health-oriented Leadership is associated with improved employee well-being and reduced stress levels, e.g., [

8,

63], supporting the effectiveness of practical applications of the HoL approach. In light of this evidence, our findings highlight the importance of integrating such practices into leadership training and organizational health management.

Leaders’ StaffCare behaviors can affect employees’ SelfCare and, consequently, their health and motivation outcomes. Leaders need to be aware not only of potential health risks but also that even occasional health-compromising behaviors, despite generally high levels of StaffCare (as seen with Health Sacrificers), can lead employees to mirror similar health-endangering behaviors. This can create an environment where awareness of health risks is present, yet boundaries are occasionally overstepped, and efforts in health promotion are neutralized. This can then result in high levels of strain and health complaints, almost as severe as those seen in dyads of Health Compromisers who do not prioritize their employees’ health at all.

While some employees, such as

Health Proactives, may maintain their SelfCare even under the guidance of disengaged leaders (

Bystanding Leaders), our research shows that this can negatively affect their overall engagement and commitment. In the current climate of skill shortages, this presents a major concern, as these employees may be more inclined to leave the organization [

64]. On the other hand, our findings also highlight that StaffCare plays a crucial role in fostering stronger employee commitment. Promoting StaffCare as an organizational value could help address this challenge by not only enhancing employee health but also strengthening their connection to the organization. This can be achieved by providing leaders with concrete tools and actionable plans that can be easily integrated into their daily routines. For example, regular health check-ins between leaders and employees should be established to foster open communication about well-being and health. These check-ins can help identify early warning signals of strain or burnout and provide leaders with opportunities to offer timely support and intervention [

65].

Moreover, training programs must emphasize the importance of leaders taking responsibility for their employees’ health rather than shifting this burden onto the employees themselves (as observed in

Bystanders). In cases where leaders do not feel responsible, our study highlights the critical role of fostering supportive work environments that empower employees to engage in their SelfCare actively [

15]. These supportive conditions, such as adequate job resources and manageable job demands, are critical factors in determining whether employees can engage in health-promoting behaviors. Previously developed interventions could include revising workloads, adjusting performance expectations [

66], or providing additional support resources, such as wellness initiatives [

67].

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Directions

This study has some limitations. First, our study focused only on the shorter-term relationship between the dyad of leaders’ StaffCare and employees’ SelfCare and the health- and motivation-related outcomes assessed three months later. For future research, it would be advisable to consider longer intervals between measurement points. For example, assessing outcomes six months or one year after measuring StaffCare and SelfCare could help to capture more extended effects and trends over time [

68]. This approach is important because higher motivational outcomes may be more short-lived, while health outcomes could weaken further over a longer period. This may have led to an underestimation of effects in our study, with different long-term trends potentially emerging in the outcomes. Additionally, incorporating multiple measurement points could help illustrate outcome trajectories across the different profiles [

10]. In addition, it would be interesting to explore other aspects of health beyond strain and health complaints, including objective measures of health such as heart rate variability. Furthermore, other outcomes, such as performance, could also be considered in future studies.

Second, the methodological approach also entails limitations. Latent Profile Analysis relies on relatively large and culturally specific samples, and the stability of identified profiles may vary depending on sample characteristics and model assumptions. For instance, LPA profiles identified in one cultural context may not readily generalize to other populations, highlighting the need for replication across diverse cultural and occupational samples [

69].

Third, there are also limiting factors regarding the practical application of the Health-oriented Leadership framework. Leaders may face contextual constraints such as limited resources, competing role demands, or work interruptions (e.g., frequent disruptions, multitasking requirements) [

15,

32]. Likewise, while leaders can create a supportive environment, the effectiveness of StaffCare ultimately also depends on employees’ willingness and ability to engage in SelfCare [

70]. These boundary conditions should be considered when transferring the approach into practice.

Finally, we focused only on two job demands and job resources, as the study was already extensive. However, it would be interesting to explore additional antecedents that could help forecast profile membership. For example, organizational health climate has already been studied in other contexts [

71,

72] and could also be a critical factor for beneficial profiles. Furthermore, employees are not only influenced by their leaders but also by their team, making team cohesion or PeerCare (as health-specific support behavior within the team [

70]) another potential influencing factor. Although the intensity of WFH days was not identified as a significant predictor, future research should not dismiss its potential impact, as previous studies have already demonstrated its importance for SelfCare. It might be worth considering whether the key factor is not the intensity, how many days someone works from home, but rather the availability of the option to work from home at all, or WHF-specific job demands and framework conditions at home. Future research could benefit from examining a mixed sample of exclusively office-based employees who lack any WFH options alongside hybrid employees to better understand the impact of WFH availability on SelfCare and related outcomes. Additionally, future research could examine further antecedents associated with WFH, such as its disadvantages (e.g., childcare responsibilities, isolation, and overtime) and advantages (e.g., flexible working hours, more time for breaks).