1. Introduction

Access to clean water is one of the most basic human needs. The United Nations’ 2023 World Development Report revealed that one in four people in the world (approximately 2 billion people) do not have access to safe drinking water. Additionally, almost half of the global population does not have access to adequate sanitation.

However, nowadays, the sustainable management of water resources represents a major occupation that arouses the interest of governments, practitioners, and researchers around the world. Nationally, the World Resources Institute [

1] ranked Morocco 27th among countries most at-risk of water shortage. The WRI indicates that Morocco will reach an extremely high level of water stress by 2040. To rebuild and restore water availability across the country, Morocco implemented a “National Water Plan” (PNE) in 2020, setting out an ambitious action plan to invest nearly USD 40 billion into the water sector. In 2022, an additional budget was allocated to support the National Program for Drinking Water Supply and Irrigation 2020–2027 (a subset of the National Water Plan).

This strategy is crucial given that the agriculture sector in Morocco, which contributes around 10.1% of national GDP [

2] and consumes almost 87% of the country’s water [

3] (HCP, 2020), is directly impacted.

Faced with this economic dependence and agriculture’s vulnerability to climatic hazards, this study aims to respond to the following core research question: How do water productivity and water stress affect economic growth in Morocco?

To address this question, three hypotheses were proposed:

H1. Water productivity is associated with economic growth.

H2. Agriculture value added is associated with economic growth.

H3. Renewable fresh water is associated with economic growth.

This study makes an original contribution to understanding the link between economic growth and water stress in Morocco, a country facing increasing challenges in terms of water scarcity. While a great deal of research exists at the global and regional (MENA) level [

4,

5,

6], there is a lack of studies regarding the existing background that analyze the Moroccan case, using advanced time-series econometric methods.

This study makes a significant research contribution to sustainability and environmental concerns by using the ARDL model to investigate the interaction between GDP, agricultural value added, renewable water resources, and water productivity. Unlike existing studies that predominantly use CO2 emissions to validate the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis in Morocco, this research focuses only on water stress as an environmental factor that could impact economic growth and the agriculture sector. This study offers a fresh perspective emphasizing, empirically, the importance of water resources in Morocco’s economic and agricultural sectors. The approach not only addresses a significant gap in the current literature but also delivers critical insights for policymakers striving to achieve sustainable economic growth while managing water resources effectively.

This study is presented in four sections: After the introduction,

Section 2 presents a description of the existing literature related to economic growth, agriculture water use, and water stress in Morocco.

Section 3 presents a spatial analysis of the Moroccan water warries context, challenges, and policies adopted by the country.

Section 4 presents the data and the empirical approach employed in this research.

Section 6 provides the empirical findings of the ARDL Model. In

Section 7, some concluding remarks and recommendations are made.

2. Literature Review

The international literature on the link between economic growth and environmental degradation has expanded considerably since the concept of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) was formalized by Grossman and Krueger [

7], following on from the seminal work of Kuznets [

8]. The EKC postulates an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic wealth (generally measured by GDP per capita) and indicators of pollution or pressure on the environment: at the beginning of the development process, economic growth is accompanied by environmental deterioration, then above a certain income threshold, stricter policies, better environmental governance, and the adoption of clean technologies promote improvements in environmental quality [

7,

9].

Initially applied to air pollutant emissions, the EKC was then tested on multiple environmental dimensions, including water management and water stress. For example, David Katz [

10] shows that, in several regions of the world, freshwater withdrawals increase with growth, but tend to stabilize, or even decrease, as societies reach a certain level of development and invest in water efficiency and reuse.

Numerous recent works have set out to explore this dynamic in a variety of geographical contexts:

- -

Esen et al. [

11], focusing on the Eurozone, confirms the existence of an EKC between GDP per capita and water stress indicators, highlighting the key role of European regulation, investment in innovation, and the rise in environmental policies.

- -

Gu et al. [

12], for China, observe that the rapid transition to a more tertiary economy and the strengthening of water-saving public policies have reversed the upward trend in water withdrawals, especially in large metropolises and intensive agricultural basins.

- -

Katz [

10], through a multi-country analysis, demonstrates that the exact shape of the curve (inverted U or not) depends on the type of indicator used (total abstraction, water stress, and per capita availability) and the level of institutional development.

Furthermore, the literature insists that the EKC relationship can be influenced by sectoral factors: Saidamatmatov et al. [

13] in Central Asia, Dai, D. et al. [

14] in China, and Arbulu et al. [

15] for the Eurozone, highlight that water consumption in sectors such as agriculture, industry, and tourism plays a decisive role in the evolution of water stress.

For example, irrigated agriculture is identified as the main driver of water stress in developing economies, whereas in advanced economies, improved water productivity and technological innovation enable a partial decoupling between growth and water consumption [

10,

16].

The econometric method favored for these studies varies, from dynamic panel models (GMM and FMOLS) to the ARDL approach to capture short- and long-term effects [

13]. The inclusion of explanatory variables such as the sectoral structure of GDP, energy consumption, investment in clean technologies, or public water allocation policies enriches the analysis and refines our understanding of the phenomenon [

9,

11].

Finally, some works warn against a mechanical reading of the EKC: the drop in pressure on water observed in certain advanced countries can also be explained by the relocation of water-intensive industries to emerging countries, or by trade-offs that are sometimes unfavorable to certain ecosystems [

10]. As a result, we need to think in terms of the global water footprint and integrate the notion of international trade into the analysis.

In Morocco, the literature on the relationship between economic development and water stress has developed more recently, in response to the worsening national water deficit and growing awareness of water security issues. The major empirical contribution in this scope is conducted by Moussaid et al. [

17], who test the Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis over the period 1980–2017 using Tapio decoupling index to link real GDP per capita, water demand, urbanization, and sectoral structure. Their results reveal an inverted U-shaped relationship, with a turning point located at an intermediate level of per capita income, beyond which pressure on water resources tends to decrease. This dynamic is mainly attributed to improved water governance, economic diversification, and the rise in water-saving irrigation technologies (drip irrigation, desalination plants, etc.).

Taheripour et al. [

18] conduct a study by using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model, that water scarcity and changes in crop yields induced by climate change could reduce the GDP of Morocco up to 6.7 billion US dollars per year at 2016 constant prices and eliminate many job opportunities, particularly in the rural region.

Elame et al. [

19] develop an economic model based on positive mathematical programming for showing that the basin’s water resources, in Sous-Massa (Morocco), are substitutable and that a sound water management policy has to integrate both surface and groundwater resources to reduce the price of water.

On the other hand, Boudhar et al. [

20] use an input-output (I-O) model of water use to analyze the intricate relationships between economic sectors and water resources in Morocco, and found that the agriculture, hunting, and forestry sector exhibits high direct water use compared to secondary and tertiary sectors that display low direct use and high indirect water use.

Other studies, such as Et-Touil [

21], qualitatively extend the analysis by incorporating additional factors such as water stress, food security, and population growth. The author shows that Moroccan agriculture remains the sector most vulnerable to water scarcity, but that significant progress has been made in water use efficiency thanks to proactive public policies (Plan Maroc Vert, Programme National d’Économie d’Eau d’Irrigation—PNEEI). Nevertheless, the persistence of recurrent droughts, demographic pressure, and dependence on irrigated crops continue to pose a major risk to the sustainability of the agricultural development model.

National literature also points to the importance of institutional determinants and adaptation strategies: recent analyses stress the need for integrated resource management, strengthened local water governance, and better coordination between agricultural, environmental, and industrial policies [

17,

21]. Some studies, fewer in number, propose broadening the research spectrum to include the impact of foreign trade on the country’s water footprint, or the effect of technology transfers on water use intensity [

22].

Overall, the previous studies that have discussed the interaction between water and economic growth in Morocco lack an econometric model that could analyze the long-run (cointegrating) and short-run relationships between those variables. Furthermore, the existing literature does not adopt a mixed methodology that could advance a qualitative and quantitative analysis, to highlight the overview of Moroccan environmental and economic context and policies, and investigate empirically the effect of water scarcity on economic growth.

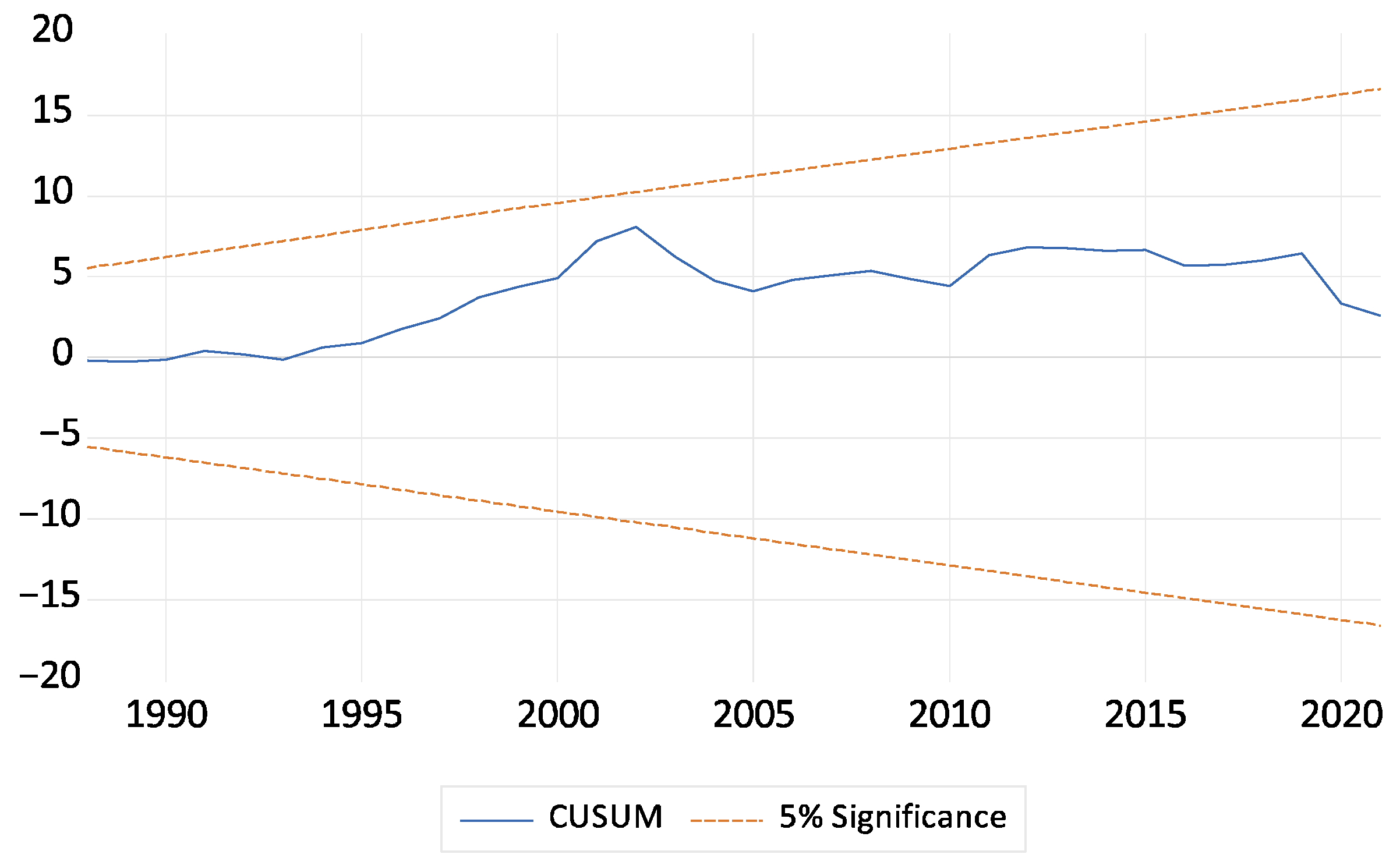

The present research is unique compared to previous studies in both methodological approach and econometric methods. Unlike the existing literature, our research advances a mixed methodology and adopts a rigorous empirical approach based on the ARDL model. In addition, this research fills a gap in the literature by proposing an updated long-term analysis, considering recent policy developments and climate variability.

3. Overview of the Moroccan Context

Sustainable water management is one of the major challenges facing global development today. Some 2 billion people still do not have access to safe drinking water, according to the United Nations World Development Report [

23], highlighting the extent of water inequalities [

24]. The situation is worrying as the demand for fresh water continues to grow because of urbanization and the expansion of the industrial and agricultural sectors [

2].

Sanitation infrastructures also show major disparities. Statistics highlight that only 54% of the world’s population had access to safely managed sanitation facilities in 2020 [

25], while over 3.6 billion people lived in areas with inadequate access to sanitation. This limited access to water and sanitation has considerable implications on public health, human development, and socio-economic stability [

23].

According to the FAO report, nearly 70% of the world’s freshwater withdrawals are used for irrigation, accentuating competition for resources with the domestic and industrial sectors [

16]. This dependence of agriculture on water, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions, highlights the sensitivity of food security to variations in water availability [

24]. Moreover, the impacts of climate change, which are accentuated by the increasing frequency and intensity of droughts, soil degradation, and reduced rainfall, are further aggravating global water stress [

26].

Morocco, as a developing country, has achieved significant strides in economic growth, driven by strategic reforms that have enhanced its competitiveness [

3]. However, the nation faces pressing climate change challenges, including water scarcity. This section aims to present, firstly, an overview of the value added of the agriculture sector in Morocco; secondly, Moroccan environmental and water challenges; and thirdly, the main national environmental strategies and laws adopted related to water.

3.1. Agriculture Added Value in Morocco

Agriculture remains a fundamental pillar of Moroccan economic growth, making a significant contribution to wealth creation and socio-economic stability in the Kingdom. The role of this sector is strategic. It has a direct impact on food security, rural employment, and trade, and the country’s macroeconomic trajectory [

3].

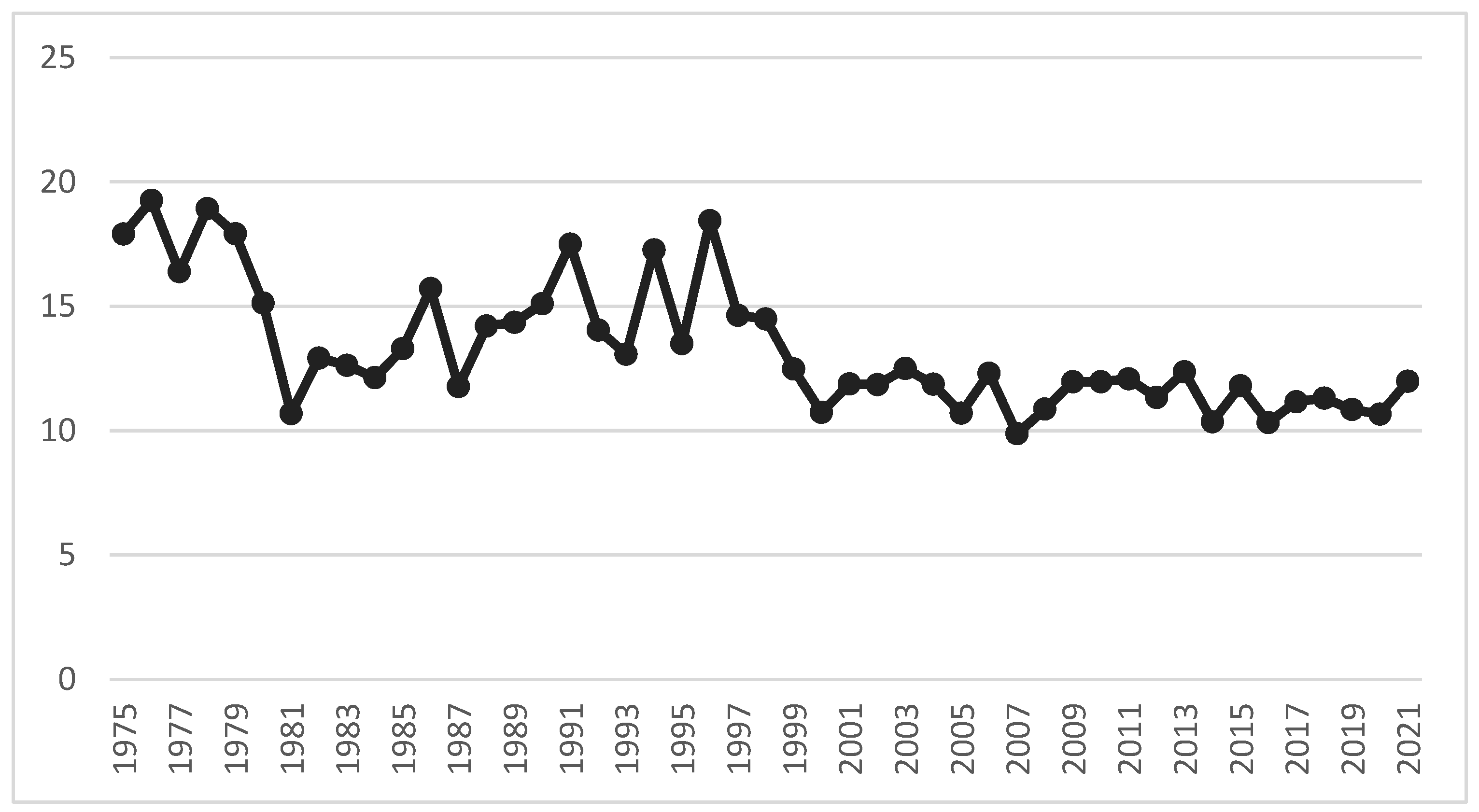

Figure 1 highlights the declining role of agriculture in Morocco’s national wealth since the mid-1970s. After an initial sharp fall, the share of agricultural value added appears to have stabilized at around 12% of GDP over the last twenty years. This change reflects the transformation of the Moroccan economy, which has gradually diversified towards industry and services. Despite this development, agriculture remains an important pillar, both for employment and food security. However, the sector’s heavy dependence on water resources makes the Moroccan economy particularly sensitive to water stress and climatic shocks [

27].

3.2. Water in Morocco: Environmental Challenges

In this alarming global context, Morocco is a particularly iconic case study regarding a country with a semi-arid to arid climate. It is experiencing structural stress in water resources, aggravated by recurrent droughts and rapid growth in demand [

26]. Morocco ranks as the 27th country in the world most exposed to the risk of water scarcity according to the last ranking of World Resources Institute (2023) [

1]. Annual per capita freshwater availability has fallen drastically in recent decades, from over 2000 cubic meters per person in the 1960s to less than 600 cubic meters today, well below the water stress threshold set by the World Bank [

2,

29].

This deterioration can be explained by several concurrent factors. On one side, population growth, rapid urbanization, and rising living standards have led to a significant increase in water requirements, notably for food, hygiene, industry, and, above all, agriculture [

22].

On the other side, Morocco remains very dependent on irrigated agriculture, which mobilizes 87% of national freshwater withdrawals [

23].

Intensive irrigation, overexploitation of groundwater, and the low efficiency of irrigation systems all contribute to increasing pressure on water resources and accelerating the degradation of aquatic ecosystems [

12].

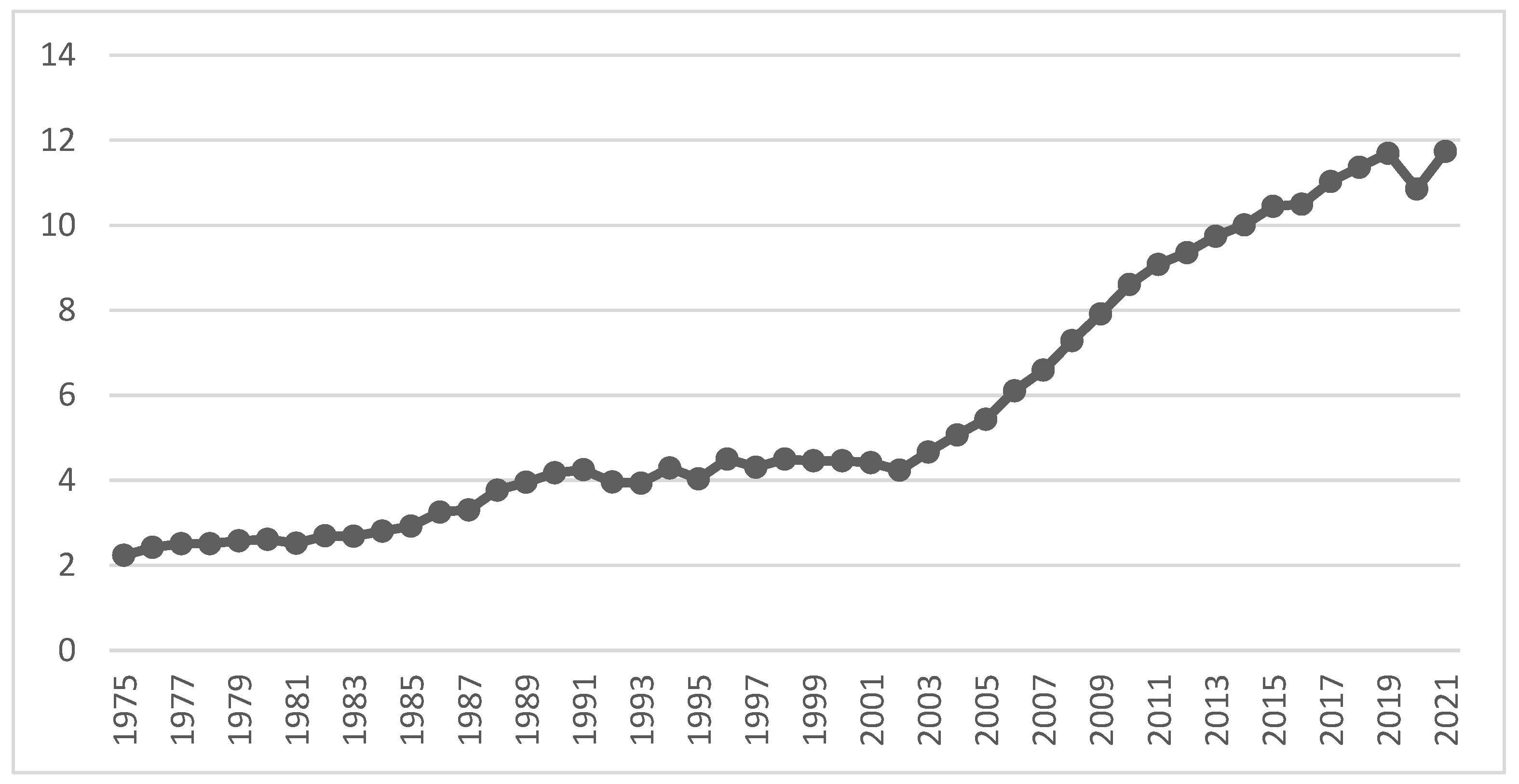

Figure 2 highlights the steady decline in renewable freshwater resources available per capita in Morocco since 1975. We can clearly see that the country has gone from a comfortable situation to a level that is now considered critical, below the threshold of 1000 m

3 per capita per year. This trend is the combined reflection of a growing population and increasingly scarce water resources, under the combined effect of climate change and overexploitation [

16]. This trend explains why Morocco is now one of the most vulnerable countries to water stress in the MENA region and highlights the need to adopt water management that is both integrated and sustainable [

26].

Finally,

Figure 3 clearly shows that water productivity in Morocco, expressed in constant 2015 dollars per cubic meter, has risen sharply, especially since the 2000s. In other words, each cubic meter of water used now contributes more to wealth creation. This encouraging trend is undoubtedly the result of efforts to make water use more efficient, through the modernization of agriculture and the adoption of new irrigation technologies [

2]. However, it is important to bear in mind that this rapid progress may also signal growing pressure on water resources, raising the question of the balance between economic development and sustainable water management [

30].

To face these challenges, several reports stress the need for integrated sustainable management of water resources, combined with innovative policies and enhanced international cooperation [

23,

31]. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal No. 6 (SDG 6) specifically aims to guarantee universal access to water and sanitation by 2030, but many countries are still a long way from achieving this target [

28]. Morocco has made notable progress in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, with an achievement of 75% for safely managed drinking water services (SDG indicator 6.1.1, 2022) and 70% as a degree of implementation of integrated water resources management (SDG indicator 6.5.1, 2023). However, there are still gaps and challenges to overcome, especially in water stress with an achievement of only 51% in 2021 (SDG indicator 6.4.2, 2021).

3.3. National Environmental Strategies

Water management thus represents a strategic challenge for Moroccan economic growth. Resource scarcity is likely to hamper the development of key sectors, including agriculture, tourism, and the agri-food industry, while exacerbating regional inequalities and the vulnerability of rural populations [

22]. In addition, climate projections for the country predict a worsening water deficit, reduced rainfall, and rising temperatures, which will make water management even more complex [

23].

Faced with this situation, the Moroccan authorities have engaged in several reforms and strategies, such as the implementation of the National Drinking Water Supply and Irrigation Program (PNAEPI) and the promotion of water-saving technologies (desalination, drip irrigation, etc.), but the results are still not adequate to growing needs [

30]. The issue of the water-economic growth nexus is therefore central to guaranteeing the resilience and sustainability of the Moroccan development model in the decades to come [

27].

To rebuild and restore water availability nationwide, Morocco launched its National Water Plan (PNE) in 2020, committing nearly

$40 billion to the sector [

3]. This initiative was further bolstered in 2022 with an additional budget allocation for the National Program for Drinking Water Supply and Irrigation 2020–2027, which operates as a component of the broader PNE [

29]. These efforts build upon the foundational strategies initiated by the earlier Plan Maroc Vert (PMV), launched in 2008, which significantly emphasized the modernization of irrigation techniques, such as widespread adoption of drip irrigation, to enhance water use efficiency within the agricultural sector and reduce water losses.

7. Conclusions

This study highlights the important role of water productivity in Morocco’s resilience to the increasing scarcity of water resources and economic growth. The results confirm that, while the short-term links between water productivity and GDP are robust, the long-term relationship between growth and water resources remains more nuanced, notably because of water variability and exogenous shocks. This Moroccan specificity can be explained by the structural importance of the agricultural sector and the country’s high exposure to climatic conditions.

In this context, Morocco has promoted ambitious policies, such as the National Water Strategy 2009–2030 and the Green Morocco Plan (Plan Maroc Vert), aimed at encouraging integrated resource management. precision irrigation and modernization of the agricultural sector [

16,

26]. The importance given to saving water, diversifying supply sources, and encouraging research and development into water technologies reflects the national will to adapt the development model to environmental constraints.

However, to build resilience and ensure inclusive growth, it is crucial to continue efforts in water governance. investment in infrastructure, and integration of water planning with economic and social policies. Establishing better monitoring indicators and systematically integrating climate change risks into decision-making remain major challenges for Morocco [

28].

In sum, the Moroccan experience offers valuable lessons for countries facing similar challenges in the MENA region and beyond. Continuously improving water productivity and promoting adaptive management, based on science and innovation, are the major levers for ensuring water security and supporting sustainable economic development in the Kingdom.