Perugia, City Walls and Green Areas: Possible Interactions Between Heritage and Public Space Restoration

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The Aurelian Walls in Rome (Esquilino, San Giovanni)Subject to several restoration initiatives aimed at enhancing the perimeter greenery and designing continuous pedestrian routes along the wall’s path. Although not yet fully completed, the project demonstrates a virtuous and integrated vision.

- The City Walls of FerraraRedeveloped as a continuous linear park with pedestrian walkways, cycling paths and resting areas. The intervention is part of the city’s Green Belt and has received European recognition for its landscape and functional value.

- The City Walls of Cittadella (Padua)Fully restored and accessible even at height through the recovery of the patrol walkways. The project has enhanced the surrounding green areas through the controlled planting and maintenance of native tree species following sustainable principles.Complementary to these are notable European examples, including the following:

- The Defensive Walls of Carcassonne (France)A UNESCO World Heritage site, restored through a conservation-driven approach integrated with rigorous green management practices to prevent damage caused by root systems. The initiative stands out for its successful integration of landscape and tourism.

- The Historic Walls of Dubrovnik (Croatia)Harmoniously embedded in the coastal landscape and Mediterranean vegetation. Strict regulations ensure that the surrounding greenery remains consistent with the site’s historical identity.

2. Historical Evolution

3. Collaborations

4. Critical Analysis of Case Studies

4.1. Case Studies

4.1.1. Porta Eburnea

- Preliminary dry cleaning using brushes, spatulas and vacuum cleaners aimed at removing surface deposits, guano, etc.;

- Disinfection with nitrogen organic compound biocide applied in two coats, with the second application 7–10 days after the first;

- Localised biocide treatment on areas with the most aggressive biological colonisation;

- Preliminary filling of cracks and voids by means of the filler (powder of material consistent with the pre-existing one) and the pouring of mortar as a binder;

- Re-adhesion of flakes on travertine surfaces;

- Cleaning with a low-pressure, non-aggressive, deionized-hot-water pressure washer with a high solvent action;

- Chemical–physical cleaning in areas affected by detrital crusts and extensive patinas with a poultice based on AB57 liquid cleaning solution mixed with a supporting product;

- Final chromatic retouching;

- Mechanical dry cleaning with precision tools such as the sorghum brush;

- Removal of cement-based filler followed by macroscopic filling;

- Integration of missing parts, with or without stainless steel pins;

- Final disinfestation treatment using slow-release biocides to prevent the development of micro- and/or macroflora;

- Final chromatic revision.

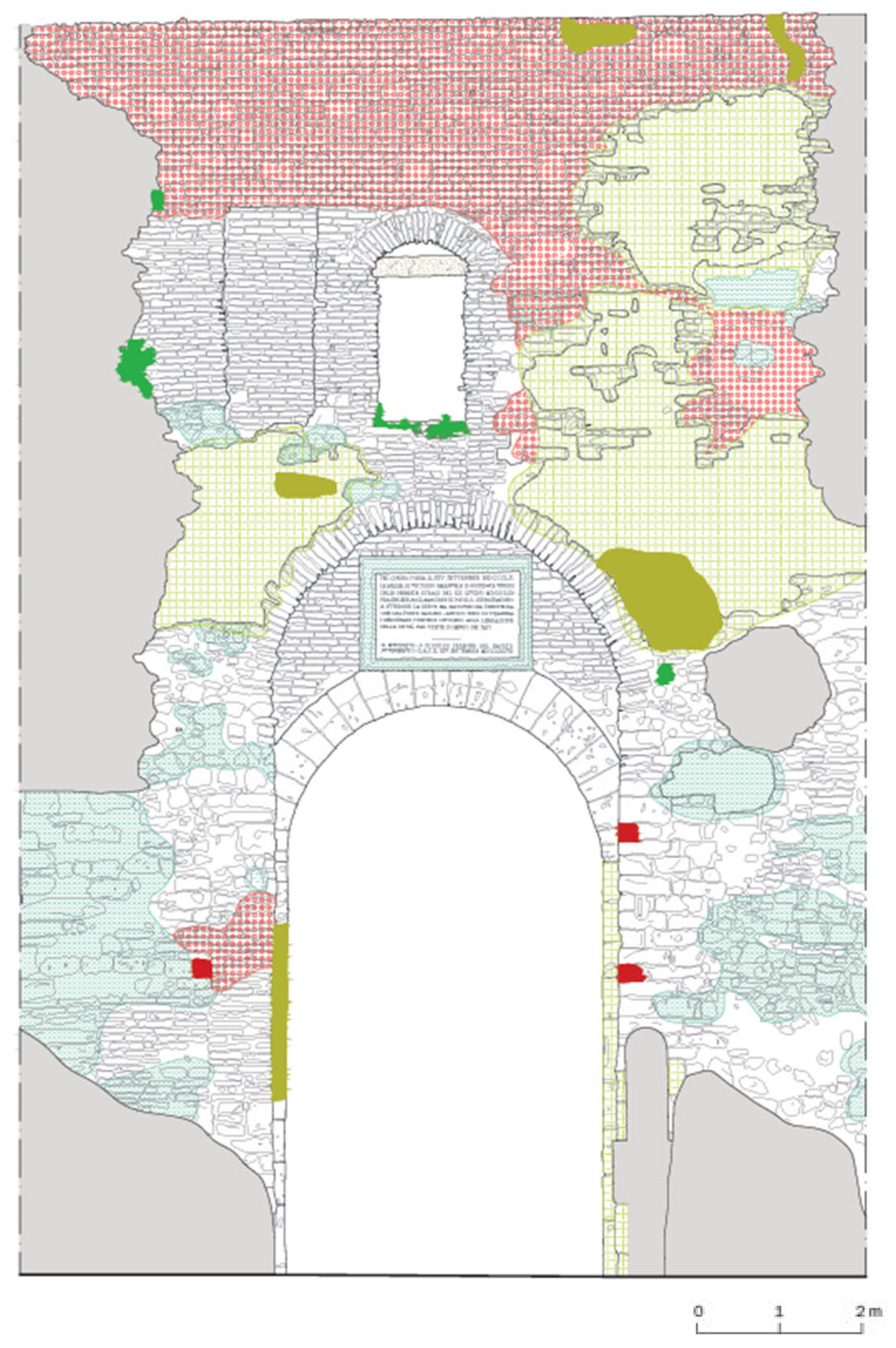

4.1.2. Porta Sant’Antonio

- Dry mechanical removal of loose surface deposits using soft brushes and natural fibre brooms;

- Preventive adhesion of any materials at risk of detachment, consistent with the pre-existing limestone;

- Localised pre-consolidation by brush application of ethyl silicate to increase the surface cohesion of the stone materials;

- Pre-consolidation by injections of desalinated lime-based fluid mortars for filling or stabilising detached areas;

- Remediation interventions on cavities, metal flashings and metallic elements;

- Inspection of all existing mortar/cement fillings and overlays, with mechanical removal or reduction as needed;

- Disinfestation of invasive vegetation through the application of nitrogen organic herbicides and the mechanical dry removal of residues with wooden spatulas;

- Cleaning of incoherent deposits and greyed areas;

- Consolidation and integrations: micro-stitching of stone and elements and filling and micro-filling with brick consistent with the pre-existing brick to provide support to the upper stone elements;

- Construction of a lime mortar cresting “cap” on the top of the wall;

- Surface protection through the application of an organic protective material to obtain a water-repellent but vapour-permeable surface, obtaining the final aesthetic presentation.

4.1.3. Critical Analysis

4.2. Parco della Cupa

5. Conclusions and Future Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malacrino, C.G. Ingegneria dei Greci e dei Romani; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bilancia, M. Il Muro Nascosto—Alla Scoperta Delle Mura Antiche di Perugia; Tozzuolo Editore: Perugia, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ischia, U.; Bianchettin Del Grano, M. La Città Giusta. Idee di Piano e Atteggiamenti Etici. Con Scritti di Bernardo Secchi e Kaveh Rashidzadeh; Donzelli Editore: Roma, Italy, 2012; p. XVIII-160. [Google Scholar]

- Art Bonus. 2023. Available online: https://artbonus.gov.it/complesso-delle-mura-urbane.html (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Okey, T. The Story of Avignon; J. M. Dent & Sons: London, UK, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, U. Le mura medievali di Perugia. In L’Umbria e Perugia nel Medioevo e Nella Prima Età Moderna; Bartoli Langeli, A., Ed.; Fondazione Centro Studi Medievali e Umanistici: Spoleto, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Belforti, G.; Mariotti, A. Illustrazioni Storico-Topografiche Della Città di Perugia; Manuscript; Biblioteca Comunale Augusta: Perugia, Italy, 1416. [Google Scholar]

- Benucci, G. La Rocca Paolina di Perugia. Studi e Ricerche; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1992; pp. 1–220. [Google Scholar]

- Maiorca, U. Torri e pozzi della Perugia medievale. Medioevo 2015, 203, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Belardi, P.; Martini, L.; Menchetelli, V. La Rocca Paolina di Perugia. Da baluardo dell’inaccessibilità a landmark dell’accessibilità. Defensive Archit. Mediterr. 2020, 8, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Guarneri, M.; Ceccarelli, S.; Francucci, M.; Liberotti, R.; La Torre, M. Multi-sensor analysis for experimental diagnostic and monitoring techniques at San Bevignate Templar Church in Perugia. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belardi, P.; Gusella, V.; Liberotti, R.; Sorignani, C. Built Environment’s Sustainability: The Design of the Gypso|TechA of the University of Perugia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia. Decreto-Legge 31 Maggio 2014, n. 83—Disposizioni Urgenti Per la Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale, lo Sviluppo Della Cultura e Il rilancio del Turismo; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2014; Serie Generale n. 125; Suppl. Ordinario n. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Italia. Decreto-Legge 8 Agosto 2014, n. 106—Disposizioni Urgenti in Materia di Cultura e Turismo; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2014; Serie Generale n. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Donelli, C.C.; Mozzoni, I.; Badia, F.; Fanelli, S. Financing Sustainability in the Arts Sector: The Case of the Art Bonus Public Crowdfunding Campaign in Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniazzi, S. Conservazione dei beni culturali, mecenatismo e Art Bonus. In Arte, Cultura e Ricerca Scientifica. Atti del Convegno AIPDA, Reggio Calabria, 4–6 Ottobre 2018; AIPDA, Ed.; AIPDA: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montella, M. Perugia; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1993; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Briganti, F. Guida Toponomastica di Perugia; Grafica Salvi & C.: Perugia, Italy, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Zappelli, M.R. Cario Viario. Un Viaggio Nella Vecchia Perugia Attraverso le Sue Mura, Porte, vie e Piazze; Tipografia Literaria: Perugia, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marcaccioli, E. Porta Eburnea, Caserta e le fonti di Veggio; Futura Libri: Perugia, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vitruvio. De Architectura, 3rd ed.; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1563. [Google Scholar]

- Croci, G. The Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage; WIT Press: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mosiu, A.; Ion, R.M.; Onescu, I.; Mosiu, M.L.; Bunget, O.C.; Iancu, L.; Grigorescu, R.M.; Ion, N. Architectural Heritage Conservation and Green Restoration with Hydroxyapatite Sustainable Eco-Materials. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguchi, C.T.; Yu, S. A review of theoretical salt weathering studies for stone heritage. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzurra, M.; Trabalza, A. Archi, Porte, Palazzi di Perugia; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fortini, A. I Bersaglieri alla Liberazione di Perugia il 14 Settembre 1860; Perugia, Italy, 1910; Available online: https://www.borgosantantonio.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Presa-di-Perugia.-Scritto-del-Prof.-Arnaldo-Fortini.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Marcaccioli, E. Sant’Antonio e Fontenuovo. Due Borghi del Rione del Sole; Futura Libri: Perugia, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Puppio, M.L.; Sassu, M. Damage and Restoration of Historical Urban Walls: Literature Review and Case of Studies. Frat. Ed Integrità Strutt. 2023, 65, 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Collepardi, M. Degradation and restoration of masonry walls of historical buildings. Mater. Struct. 1990, 23, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberotti, R.; Cavalagli, N.; Cluni, F.; Gioffrè, M.; Pepi, C.; Gusella, V. Defence of architectural heritage: Experimental campain on masonries reinforced with natural FRCM compositive materials. Compdyn Proc. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cluni, F.; Faralli, F.; Gusella, V.; Liberotti, R. X-ray CT and Mesoscale FEM of the Shot-Earth Material. In Shot-Earth for an Eco-friendly and Human-Comfortable Construction Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, G. An Italian contribution of architectural restoration. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, G. Avvicinamento al Restauro. Teoria, Storia, Monumenti; Liguori Editore: Napoli, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter); ICOMOS: Venice, Italy, 1964; Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Charter-of-Venice_1964.pdf?utm (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage; ICOMOS: Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 2003; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters-and-doctrinal-texts/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Società Italiana per il Restauro dell’Architettura (SIRA). Linee Guida per il Restauro Architettonico; SIRA: Roma, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.sira-restauroarchitettonico.it (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- UNI 11182: 2006; Materiali Lapidei Naturali ed Artificiali: Descrizione della Forma di Alterazione—Termini e Definizioni. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione: Milano, Italy, 2006.

- El-Gohary, M.A. Environmental impacts: Weathering factors, mechanism and forms affecting the stone decaying in Petra. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 135, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, R.; De Medici, M.; Fiore, S. Durability and degradation of natural stone in Syracusan façades. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture VIII; Brebbia, C.A., Ed.; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2004; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Matoušková, E.; Kovářová, K.; Cihla, M.; Hodač, J. Monitoring biological degradation of historical stone using hyperspectral imaging. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.H.; Silva, A.; de Brito, J.; Ekhlassi, A.; Hosseini, S.B. Degradation Assessment of Natural Stone Claddings over Their Service Life: Comparison between Tehran (Iran) and Lisbon (Portugal). Buildings 2021, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, R. Archeologia e contesto: Il ruolo del restauro. Mater. E Strutt. 2018, 13, 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, A.; Thamarat, M. How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Baratin, L. The walls of Urbino: A project of restoration, conservation and enhancement integrated in the historical city. In Contributo Atti di Convegno; Iris: Urbino, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pastukh, O.; Gray, T.; Golovina, S. Restored layers: Reconstruction of Historical Sites and Restoration of Architectural Heritage: The Experience of the United States and Russia (Case study of St. Petersburg). Archit. Eng. 2020, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, E.T. A Brief History of the Restoration of the Theodosian Walls Before the Twenty-first Century. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Tech. W Katowicach 2023, 16, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Park, S. VLAS: Vacant Land Assessment System for Urban Renewal and Greenspace Planning in Legacy Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Ozcevik Bilen, A.; Toma, R.A.; Akin Guler, G.; Maffei, L. The Restorativeness of Outdoor Historical Sites in Urban Areas: Physical and Perceptual Correlations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, S.; Winarto, Y.; Hardiana, A.; Su’adyo, A.; Christophori Lake, R.; Ekawati, J. Retrofit of green architecture through adaptive reuse of heritage buildings in sustainable tourism management. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, N.; Fini, A.; Senes, G.; Vacchiano, G.; Vagge, I.; Lupi, D.; Ambrosini, R.; Brambilla, M.; Boffi, M. Storia, Ricerca e Persone: Proposta di Riqualificazione Dell’area Dell’Università di Milano All’interno del Parco di Monza; Università degli Studi di Milano: Milano, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liberotti, R.; Paolocci, M. Perugia, City Walls and Green Areas: Possible Interactions Between Heritage and Public Space Restoration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156663

Liberotti R, Paolocci M. Perugia, City Walls and Green Areas: Possible Interactions Between Heritage and Public Space Restoration. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156663

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiberotti, Riccardo, and Matilde Paolocci. 2025. "Perugia, City Walls and Green Areas: Possible Interactions Between Heritage and Public Space Restoration" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156663

APA StyleLiberotti, R., & Paolocci, M. (2025). Perugia, City Walls and Green Areas: Possible Interactions Between Heritage and Public Space Restoration. Sustainability, 17(15), 6663. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156663